Page 1

Executive Summary

There is no doubt that musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities are an important and costly national health problem. Musculoskeletal disorders account for nearly 70 million physician office visits in the United States annually and an estimated 130 million total health care encounters including outpatient, hospital, and emergency room visits. In 1999, nearly 1 million people took time away from work to treat and recover from work-related musculoskeletal pain or impairment of function in the low back or upper extremities. Conservative estimates of the economic burden imposed, as measured by compensation costs, lost wages, and lost productivity, are between $45 and $54 billion annually. There is some variation in estimates of occurrence and cost as a result of inconsistencies within and across existing databases. The ability to better characterize the magnitude of the problem and formulate targeted prevention strategies rests on improved surveillance and more rigorous data collection.

There is also debate concerning sources of risk, mechanisms of injury, and the potential for intervention strategies to reduce these risks. The debate focuses on the causes, nature, severity, and degrees of work-relatedness of musculoskeletal disorders as well as the effectiveness and cost-related benefits of various interventions. None of the common musculoskeletal disorders is uniquely caused by work exposures. They are what the World Health Organization calls “work-related conditions” because they can be caused by work exposures as well as non-work factors. There are a number of factors to be considered: (1) physical, organizational, and social aspects of work and the workplace, (2) physical and social aspects of life outside the workplace, including physical activities (e.g., household work, sports, exercise programs), economic incentives,

Page 2

and cultural values, and (3) the physical and psychological characteristics of the individual. The most important of the latter include age, gender, body mass index, personal habits including smoking, comorbidities, and probably some aspects of genetically determined predispositions. In addition, physical activities away from the workplace may also cause musculoskeletal syndromes; the interaction of such factors with physical and psychosocial stresses in the workplace is a further consideration. The task herein is to evaluate the significance of the risk factors that result from work exposure while taking into account the different types of individual and non-work factors. The complexity of the problem is further increased because all of these factors interact and vary over time and from one situation to another. Research is needed to clarify such relationships, but research is complicated by the fact that estimates of incidence in the general population, as contrasted with the working population, are unreliable because the two overlap: more than 80 percent of the adult population is in the workforce.

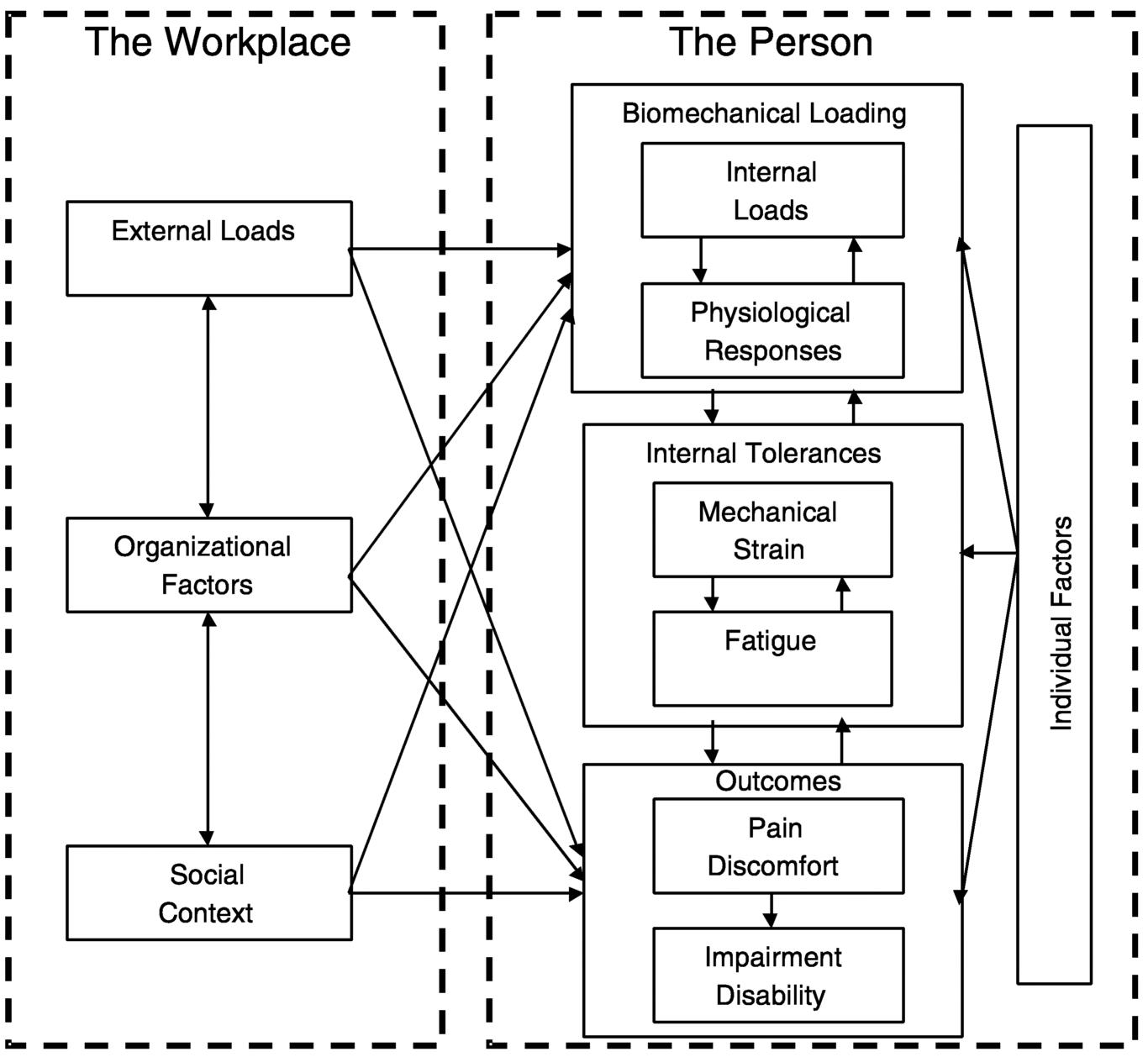

The panel approached the complex of factors bearing on the risk of musculoskeletal injury in the work setting from a whole-person perspective, that is, from a point of view that does not isolate disorders of the low back and upper extremities from physical and psychosocial factors in the workplace, from the context of the overall texture of the worker's life, including social support systems and physical and psychosocial stresses outside the workplace, or from personal responses to pain and individual coping mechanisms (see Figure ES.1).

The size and complexity of the problem and the diversity of interests and perspectives—including those of medical and public policy professionals, behavioral researchers, ergonomists, large and small businesses, labor, and government agencies—have led to differing interpretations of the evidence regarding the work-relatedness of musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities and the impact of interventions. As a result, Congress requested a study by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine covering the scientific literature on the causation and prevention of these disorders. The congressional request was presented in the form of seven questions, which are addressed in Appendix A of this report. The funding for the study was provided by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

PANEL CHARGE, COMPOSITION, AND APPROACH

The charge to the panel from NIOSH and NIH was to undertake a series of tasks that would lead to a detailed analysis of the complex set of factors contributing to the occurrence in the workplace of musculoskeletal

Page 3

~ enlarge ~

Page 4

BOX ES.1 The Charge1. Assess the state of the medical and biomechanical literature describing the models and mechanisms characterizing the load-response relationships and the consequences (adaptation, impairment, disability) for musculoskeletal structures of the neck, the upper extremities, and the low back. 2. Evaluate the state of the medical and behavioral science literature on the character of jobs and job tasks, the conditions surrounding task performance, and the interactions of person, job, and organizational factors and, in addition, examine the research literature on the individual and nonwork-related activities that can contribute to or help prevent or remediate musculoskeletal disorders. 3. Assess the strengths and weaknesses of core datasets that form the basis for examining the incidence and epidemiology of musculoskeletal disorders reported in the workplace. 4. Examine knowledge concerning programs and practices associated with primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of musculoskeletal injuries, ranging from organization-wide promotion of a safety culture to modified work and a variety of clinical treatment programs. 5. Characterize the future of work, how the workforce and jobs are changing and the potential impact of these changes on the incidence of musculoskeletal disorders. 6. Identify most important gaps in the science base and recommend needed research. |

disorders of the low back and upper extremities and that would provide the information necessary to address the questions posed by Congress. The charge appears in Box ES.1. The panel viewed this charge as an opportunity to conduct a comprehensive review and interpretation of the scientific literature, with the goal of clarifying the state of existing knowledge concerning the roles of various risk factors and the basis for various efforts bearing on prevention. The focus of the study was on work-related factors. In this context, individual risk factors, such as age, body mass index, gender, smoking, and activities outside the workplace, were considered as sources of confounding and were accounted for in the research reviews.

The panel was composed of 19 experts representing the fields of biomechanics, epidemiology, hand surgery, human factors engineering, internal medicine, nursing, occupational medicine, orthopedics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, physiology, psychology, quantitative analy-

Page 5

sis, and rheumatology. The panel's work was guided by two underlying principles. The first, noted above, was to approach musculoskeletal disorders in the context of the whole person rather than focusing on body regions in isolation. The second was to draw appropriate scientific inferences from basic tissue biology, biomechanics, epidemiology, and intervention strategies in order to develop patterns of evidence concerning the strength of the relationship between musculoskeletal disorders and the multiplicity of work and individual factors.

The panel applied a set of rigorous scientific criteria in selecting the research studies for its review. Because the literature includes both empirical and theoretical approaches and covers a wide variety of research designs, measurement instruments, and methods of analysis, the quality selection criteria varied somewhat among disciplines (see Chapter 1 for details). At one level, there are highly controlled studies of soft tissue responses to specific exposures using cadavers, animal models, and human subjects. At another level, there are surveys and other observational epidemiologic studies that examine the association among musculoskeletal disorders and work, organizational, social, and individual factors. At yet another level, there are experimental and quasi-experimental studies of human populations designed to examine the effects of workplace interventions. Each level provides a different perspective; together they provide a complementary picture of how various workplace exposures may contribute to the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders. Although each level has its attendant strengths and limitations when considered alone, together they provide a rich understanding of the causes and prevention of musculoskeletal disorders.

The wide and diverse body of literature addressing the work-relatedness of musculoskeletal disorders suggests various pathways to injury. Figure ES.1 summarizes the analytic framework used by the panel to organize and interpret these various strands of research. This framework is central to the panel's assessment, and it is used to orient and structure the panel's report. The factors are organized into two broad categories: workplace factors and characteristics of the person that may affect the development of musculoskeletal disorders. Workplace factors include the external physical loads associated with job performance, as well as organizational factors and social context variables. A person is the central biological entity, subject to biomechanical loading with various physical, psychological, and social features that may influence the biological, clinical, and disability responses. The rationale underlying the figure is that there may be many pathways to injury, and the presence of one pathway does not negate nor suggest that another pathway does not play an important role. The various pathways simply represent different aspects of the workplace-person system.

Page 6

PATTERNS OF EVIDENCE

The panel's review of the research literature in epidemiology, biomechanics, tissue mechanobiology, and workplace intervention strategies has identified a rich and consistent pattern of evidence that supports a relationship between the workplace and the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities. This evidence suggests a strong role for both the physical and psychosocial aspects of work. There is also evidence that individual factors, such as age, gender, and physical condition, are important in mediating the individual's response to work factors associated with biomechanical loading.

Back Disorders and the Workplace

Low back disorder risk has been established through epidemiologic studies of work that involves heavy lifting, frequent bending and twisting, and whole body vibration, as well as other risk factors. The relative risks have been derived from a rigorous evaluation of the literature and have been found to be strong and consistent. Strong points in this research include control for confounding, temporal association, and characterization of dose-response relationships; the principal limitation is that a number of the studies are based on self-reports of injury. The epidemiologic literature that specifically quantifies heavy lifting shows the greatest risk for injury when loads are lifted from low heights, when the distance of the load from the body (moment) is great, and when the torso assumes a flexed, asymmetric posture. Biomechanical studies reinforce the epidemiologic findings. Studies in basic biology also describe the mechanisms involved in the translation of spinal loading to tissue injury within the intervertebral disc. In addition, the basic science literature has described pathways for the perception of pain when specific structures in the spine are stressed. Intervention studies have shown how lift tables and lifting hoists are effective in mediating the risk of low back pain in industrial settings. Since risk is lowered when the load is changed from a heavy lift to a light lift, this finding is also consistent with the rigorous epidemiologic findings.

In epidemiologic studies, psychosocial factors in the workplace have also been found to play a role. Specifically, there is evidence for a relationship between low back disorders and job satisfaction, monotonous work, work pace, interpersonal relationships in the workplace, work demand stress, and the worker's perceived ability to work. In addition, recent evidence from biomechanics studies points to a mechanism whereby psychosocial stress contributes to increases in spine loading. There is also evidence that exposure to psychosocial stressors may result in greater

Page 7

trunk muscle activity independent of biomechanical load. Some part of the variance in response described in the biological and biomechanical literature appears to be explained by individual host factors, such as age, gender, and body mass index. For example, age and gender appear to play a role in determining the magnitude of load to which a person's spine may be exposed before damage would be expected.

Upper Extremity Disorders and the Workplace

The pattern of evidence for upper extremity disorders, as for the low back, also supports an important role for physical factors, particularly repetition, force, and vibration. The most dramatic physical exposures occur in manufacturing, food processing, lumber, transportation, and other heavy industries, and these industries have the highest rates of upper extremity disorders reported as work related. Psychosocial factors were found to play a role in upper extremity disorders as well, particularly high job stress and high job demands. In addition, several epidemiologic studies of physical exposures (force, repetition) and psychosocial exposure (perceived stress, job demands) have documented an elevated risk of upper extremity disorders among computer users. Nonwork-related anxiety, tension, and psychological distress are also associated with upper extremity symptoms. Biomechanical studies have shown that extraneural pressure in the carpal tunnel is increased with hand loading and nonneutral wrist postures. Basic science studies demonstrate that extraneural pressures may lead to intraneural edema and fibrosis, demyelination, and axon degeneration. These changes in nerve structure may cause impairment of nerve function. The findings in the intervention literature are congruent with those in the basic biology and epidemiology literatures. There is strong support across these bodies of work that high force and repetition are associated with musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities; basic biology data provide evidence of alteration in tissue structure. The intervention literature supports the efficacy of tool and workstation design changes, job rotation, and other interventions that directly address these risk factors with regard to upper extremity symptomology.

Although the upper extremity literature is less well developed than the literature on low back pain, an analogous set of themes emerges, lending further support to the conclusion that external loads and psychosocial factors associated with work influence outcomes. These exposureresponse associations persist when adjusted for individual factors that may increase vulnerability, such as age, gender, and body mass index. The basic biology and biomechanics studies provide a plausible basis for the exposure-response relationships. The evidence related to the efficacy of ergonomic interventions further supports these relationships.

Page 8

Interventions

Data from scientific studies of primary and secondary interventions indicate that low back pain can be reduced under certain conditions by engineering controls (e.g., ergonomic workplace redesign), administrative controls (specifically, adjusting organizational culture), programs designed to modify individual factors (specifically, employee exercise), and combinations of these approaches. Multiple interventions that actively involve workers in medical management, physical training, and work technique education can also be effective in controlling risk. Similarly, with respect to interventions for musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities, some studies of engineering controls for computer-related work (reducing static postural loads, sustained posture extremes, and rapid motions, and changing the designs of workstations and tools) have resulted in a decrease in upper extremity pain reports. Studies of administrative controls (modifying organizational culture by an emphasis on participatory team involvement) have also reported success. For such interventions, the commitment of management and the involvement of employees have been important to success.

These findings are based on a research and development process that tailors interventions to specific work and worker conditions and evaluates, on a continuing basis, the effectiveness of these interventions in the face of changing workplace and worker factors. It is therefore neither feasible nor desirable to propose a generic solution. The development and application of effective interventions requires an infrastructure that supports (1) gathering data, through surveillance and research, about the engineering, administrative, and worker factors that affect the effectiveness of interventions; (2) using these data to refine, implement, and assess alternative interventions; and (3) translating knowledge from research to practice. These efforts will benefit from cooperation and information exchange among researchers, practitioners, and workers and managers in industry and labor, government, and academia. These practices should be encouraged and extended.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on a comprehensive review and analysis of the evidence, as described above, the panel has reached the following conclusions:

1. Musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities are an important national health problem, resulting in approximately 1 million people losing time from work each year. These disorders impose a substantial economic burden in compensation costs, lost wages, and

Page 9

-

The panel concludes that there is a clear relationship between back disorders and physical load; that is, manual material handling, load moment, frequent bending and twisting, heavy physical work, and whole-body vibration. For disorders of the upper extremities, repetition, force, and vibration are particularly important work-related factors.

-

Work-related psychosocial factors recognized by the panel to be associated with low back disorders include rapid work pace, monotonous work, low job satisfaction, low decision latitude, and job stress. High job demands and high job stress are work-related psychosocial factors that are associated with the occurrence of upper extremity disorders.

productivity. Conservative cost estimates vary, but a reasonable figure is about $50 billion annually in work-related costs.

2. Estimates of incidence in the general population, as contrasted with the working population, are unreliable because more than 80 percent of the adult population in the United States is in the workforce.

3. Because workplace disorders and individual risk and outcomes are inextricably bound, musculoskeletal disorders should be approached in the context of the whole person rather than focusing on body regions in isolation.

4. The weight of the evidence justifies the identification of certain work-related risk factors for the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities.

5. A number of characteristics of the individual appear to affect vulnerability to work-related musculoskeletal disorders, including increasing age, gender, body mass index, and a number of individual psychosocial factors. These factors are important as contributing and modifying influences in the development of pain and disability and in the transition from acute to chronic pain.

6. Modification of the various physical factors and psychosocial factors could reduce substantially the risk of symptoms for low back and upper extremity disorders.

7. The basic biology and biomechanics literatures provide evidence of plausible mechanisms for the association between musculoskeletal disorders and workplace physical exposures.

8. The weight of the evidence justifies the introduction of appropriate and selected interventions to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities. These include, but are not confined to, the application of ergonomic principles to reduce physical as well as psychosocial stressors. To be effective, intervention programs should

Page 10

include employee involvement, employer commitment, and the development of integrated programs that address equipment design, work procedures, and organizational characteristics.

9. As the nature of work changes in the future, the central thematic alterations will revolve around the diversity of jobs and of workers. Although automation and the introduction of a wide variety of technologies will characterize work in the future, manual labor will remain important. As the workforce ages and as more women enter the workforce, particularly in material handling and computer jobs, evaluation of work tasks, especially lifting, lowering, carrying, prolonged static posture, and repetitive motion, will be required to guide the further design of appropriate interventions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

-

The injury or illness coding system designed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics should be revised to make comparisons possible with health survey data that are based on the widely accepted ICD-9 and ICD-10 coding systems.

-

The characterization of exposures associated with musculoskeletal disorders should be refined, including enhanced quantification of risk factors. Currently, exposure is based only on characterization of sources of injury (e.g., tools, instruments, equipment) and type of event (e.g., repetitive use of tools) derived from injury narratives.

-

Information collected from each employer should contribute to specificity in denominators for jobs including job-specific demographic features in the workplace, such as age, gender, race, time on the job, and occupation.

-

Injury and illness information should include, in addition to the foregoing demographic variables, other critical variables, such as event, source, nature, body part involved, time on the job, and rotation schedule. Combining these with the foregoing variables would, with appropriate denominator information, allow calcula-

1. The consequences of musculoskeletal disorders to individuals and society and the evidence that these disorders are to some degree preventable justify a broad, coherent effort to encourage the institution or extension of ergonomic and other preventive strategies. Such strategies should be science based and evaluated in an ongoing manner.

2. To extend the current knowledge base relating both to risk and effective interventions, the Bureau of Labor Statistics should continue to revise its current data collection and reporting system to provide more comprehensive surveillance of work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

Page 11

-

tion of rates rather than merely counts or proportions, as is now the case for all lost-workday events.

-

Resources should be allocated to include details on non-lost-workday injuries or illnesses (as currently provided on lost-workday injuries) to permit tracking of these events in terms of the variables now collected only for lost-workday injuries (age, gender, race, occupation, event, source, nature, body part, time on the job).

-

To upgrade and improve passive industry surveillance of musculoskeletal disorders and workplace exposures, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health should develop adaptable surveillance packages with associated training and disseminate these to interested industries.

-

To provide more active surveillance opportunity, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health should develop a model surveillance program that provides ongoing and advanced technical assistance with timely, confidential feedback to participating industries.

3. The National Center for Health Statistics and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health should include measures of work exposures and musculoskeletal disorder outcomes in ongoing federal surveys (e.g., the National Health Interview Surveys, the National Health and Nutritional Examinations), and NIOSH should repeat, at least decennially, the National Occupational Exposure Survey.

4. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health should take the lead in developing uniform definitions of musculoskeletal disorders for use in clinical diagnosis, epidemiologic research, and data collection for surveillance systems. These definitions should (1) include clear and consistent endpoint measures, (2) agree with consensus codification of clinically relevant classification systems, and (3) have a biological and clinical basis.

5. In addition to these recommendations, the panel recommends a research agenda that includes developing (1) improved tools for exposure assessment, (2) improved measures of outcomes and case definitions for use in epidemiologic and intervention studies, and (3) further quantification of the relationship between exposures and outcomes. Also included are suggestions for studies in each topic area: tissue mechanobiology, biomechanics, psychosocial stressors, epidemiology, and workplace interventions. The research agenda is presented in Chapter 12.

Page 12

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because of the importance of continued data collection and research to further elucidate the causes and prevention of musculoskeletal disorders of the low back and upper extremities, the panel believes it would be useful for relevant government agencies, including the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to consider the following program initiatives.

-

Developing new mechanisms and linkages among funding agencies (e.g., the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) to expand ongoing basic research on relevant tissues (e.g., skeletal muscle, tendon, peripheral nerve) to promote study of those parameters that are directly relevant to work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

-

Creating mechanisms to stimulate collaboration and cross-training of researchers in the basic and applied sciences directly relevant to work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

-

Developing mechanisms to promote research jointly conducted by industry and the relevant academic disciplines on work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

1. Expanding research support and mechanisms to study musculoskeletal disorders in terms of risk factors at work, early detection, and effective methods of prevention and their cost effectiveness. Some examples include:

2. Expanding considerably research training relevant to musculoskeletal disorders, particularly with relation to graduate programs in epidemiology, occupational health, occupational psychology, and ergonomics, to produce additional individuals with research training.

3. Expanding education and training programs to assist workers and employers (particularly small employers) in understanding and utilizing the range of possible workplace interventions designed to reduce musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, consideration should be given to expanding continuing education (e.g., NIOSH Education and Research and Training Projects) for a broad range of professionals concerning risk factors that contribute to musculoskeletal disorders inside and outside the workplace.

Page 13

-

Establishing a database of and mechanism for communicating “best practices.”

-

Providing incentives for industry and union cooperation with due regard for proprietary considerations and administrative barriers.

-

Encouraging funding for such studies from industry, labor, academia, and government sources.

4. Developing mechanisms for cooperative studies among industry, labor unions, and academia, including:

5. Revising administrative procedures to promote joint research funding among agencies.

6. Encouraging the exchange of scientific information among researchers interested in intervention research through a variety of mechanisms. Areas that could benefit include the development of (1) research methodologies, especially improved measurement of outcomes and exposures, covariates, and costs and (2) uniform approaches, allowing findings to be compared across studies. In addition, periodic meetings should be considered to bring together individuals with scientific and “best practices” experience.

In order to implement these suggestions, the scope of research and training activities of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health would have to be expanded and funding significantly increased. In addition, other federal agencies (e.g., the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health) would have to broaden their support of research programs examining musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace. In the panel's view these steps deserve serious consideration.