3

Air Force Small Business Innovation Research Program

OVERALL RESOURCES

Air Force resources allocated to the SBIR program are significant, approximately $200 million for FY00; this represents the second largest SBIR program in the federal government and about 40 percent of the resources in the total DOD SBIR program. The principal goals and objectives of the Air Force program are to support the warfighter through the insertion of SBIR-developed technological innovations into systems and subsystems and to increase both the level of participation among small businesses and the commercialization of SBIR technologies. Historically, the Air Force SBIR program has been managed by the AFRL, its S&T organization. This is still the basic approach, although recently the management stewardship was broadened to include the technology customers in order to focus on meeting critical customer requirements and improving the technology transition process.

These changes have also been driven by DOD guidance for SBIR program improvements issued by the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and technology in October 1998. Guidance on facilitating the transition of SBIR-developed technologies into DOD acquisition programs was summarized in a memorandum of August 1999 (DOD, 1999). Among the key provisions of this document is a requirement that the warfighting customer endorse at least 50 percent of the program by FY02. The long-standing baseline process and recent enhancements are described below.

Air Force SBIR resources have yielded important technological innovations and represent a significant addition to core Air Force S&T funding (PE 6.1–6.3), on the order of 16 percent in FY00 ( Table 3-1). Because the S&T core budget has been decreasing (from $2.2 billion in FY87 to $1.2 billion in FY00), the relative impact of the SBIR program has been steadily increasing. Within the two program execution directorates of AFRL—Materials and Manufacturing and Air Vehicles—that are the major participants in the aging aircraft S&T program, the increase in funding via SBIR is similar, about 16 percent ( Table 3-2).

TABLE 3-1 Proposals, Awards, and Funding for the Air Force SBIR Program (million $)

|

FY96 |

FY97 |

FY98 |

FY99 |

FY00 |

|

|

SBIR program |

|||||

|

Proposals |

3,793 |

4,003 |

3,285 |

2,794 |

2,444 |

|

Phase I awards |

354 |

393 |

439 |

411 |

356 |

|

Phase II awards |

194 |

211 |

243 |

152 |

|

|

Budget |

161.9 |

200.1 |

197.6 |

204.0 |

184.8 |

|

AFRL core budget |

|||||

|

(PE 6.1–6.3) |

1,406.3 |

1,271.6 |

1,202.7 |

1,170.7 |

1,182.8 |

|

Table courtersy of Air Force Small Business Innovation Research Office. |

|||||

TABLE 3-2 Proposals, Awards, and Funding for the SBIR Programs in the Air Vehicles and Materials and Manufacturing Directorates (million $)

|

FY |

||||||||

|

Materials and Manufacturing |

Air Vehicles |

|||||||

|

96 |

97 |

98 |

99 |

96 |

97 |

98 |

99 |

|

|

SBIR program |

||||||||

|

Proposals |

297 |

729 |

494 |

409 |

269 |

261 |

196 |

157 |

|

Phase I awards |

36 |

59 |

55 |

43 |

19 |

21 |

26 |

23 |

|

Phase II awards |

17 |

31 |

23 |

27 |

9 |

10 |

13 |

9 |

|

Budget |

12.3 |

15.1 |

32.2 |

23.7 |

12.1 |

11.9 |

10.8 |

9.6 |

|

Directorate core budget |

||||||||

|

(PE 6.1-6.3, 7.8) |

105 |

112 |

108 |

106.8 |

90.8 |

85.3 |

78.4 |

81.9 |

|

Table courtesy of Air Force Aeronautical Systems Center. |

||||||||

The source of the Air Force SBIR funds is a corporate set-aside of 2.5 percent off the top of all extramural Air Force R&D accounts. For the AFRL, this represents a “tax” on the entire S&T account, excluding that fraction of the budget used to support personnel and in-house expenditures (intramural accounts). The set-aside is also applied to the acquisition R&D accounts of the Air Force product centers and the program executive officials (PEOs). For aging aircraft, this is the Aeronautical Systems Center (ASC) and the PEO programs (such as the F-22 and the Joint Strike Fighter). Test centers and ALCs are also “taxed,” but they have a much smaller R&D base.

BASELINE PROCESS

SBIR Topics, Topic Allocation, and Phase I Contracts

The SBIR process begins with the creation of descriptions of technical topics, new technologies that would meet the requirements of key units across the entire Air Force. The descriptions, typically two pages long, reflect current research themes and requirements. After approval by DOD, these technical topics are distributed to the SBIR business community in an annual SBIR proposal solicitation published in Commerce Business Daily and on the DOD SBIR Web site, <www.acq.osd.mil/sadbu/sbir>. The full process description, the topic listing, and key contacts for administrative and technical assistance are also posted. An open preproposal period follows, during which prospective participants can engage in technical discussions with the topic sponsor. The small business community then submits Phase I proposals. The selection of Phase I proposals is competitive, based on technical merit. A current ground rule used by the Air Force is to award at least one Phase I program for each SBIR topic. On average, approximately 10 percent of proposals are awarded Phase I programs.

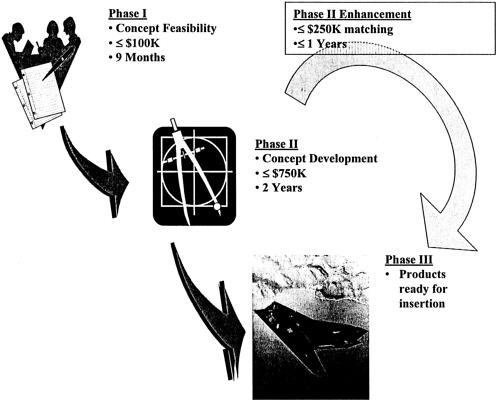

In the baseline process, the topic allocation step is important for at least two reasons. First, for small businesses, Phase I competition is the entry point into the entire process, including positioning to compete for the much larger Phase II and Phase III funding and eventual technology transition ( Figure 3-1). Second, because the number of topics is limited, Air Force participants must compete to have their topics selected for the program solicitation. If a topic is included, it assures Air Force managers that their core program will be augmented by SBIR projects and that innovations flowing from the small business community will be applicable to their needs.

Topic selection, SBIR contractor awards, and contracts administration are the responsibility of the AFRL directorates. The SBIR team at AFRL headquarters provides policy guidance, fiscal oversight, and resource allocation through established processes developed and approved by the Air Force and the AFRL.

Phase II Contracts and Phase III Implementation

If a relatively short, modestly funded Phase I program is successful, the SBIR company is invited to submit a Phase II proposal. The program awards for Phase

II are much more substantial than for Phase I. A general AFRL rule of thumb is that the number of Phase II awards should be approximately 50 percent of the number of Phase I contracts. Thus, overall, approximately 5 percent of the initial Phase I proposals lead to Phase II program awards.

To facilitate technology transition and commercialization, SBIR program provisions allow up to 33 percent of Phase I and 50 percent of Phase II programming to be shared with a partner company that is not a small business. Thus, if the eventual market for the technology is limited to the military sector, it may be attractive for the small business to team up with an aerospace industry prime contractor to facilitate technology transition. Striking the right partnership terms, particularly when it comes to protecting the intellectual property rights of small businesses, is a significant challenge.

Under the SBIR funding umbrella, there are opportunities for a Phase I fast track and a Phase II enhancement. For the Phase I fast track, if the SBIR investor offers outside capital, the Air Force will consider providing up to four times that amount in matching funds. The fast track offers expedited processing and significantly better chances of Air Force support. The Phase II enhancement process requires non-SBIR military matching funds up to $250,000 to help resolve technical barriers discovered during normal Phase II R&D. As the research proceeds, new challenges and opportunities may emerge, and the Air Force SBIR program manager may launch a new round of Phase I or II programming in the same general area to deal with these issues.

The follow-on Phase III funding from the Air Force, for example from the core AFRL S&T budget, is not generally the final step in successful technology implementation. As a practical matter, although this next step is called commercialization, in some cases the funding is used for exploratory development (PE 6.2) or advanced development (PE 6.3) that may still fall well short of the adoption of the technology by the ultimate customer. Many technologies require other phases of acquisition programming before they are considered ready for insertion into a system or subsystem. This may include demonstration and validation (PE 6.4) or engineering and manufacturing development (PE 6.5). Final customer application, for example, for an aging aircraft system like the C-141, will require acquisition funding from this SPO or sustainment funding from an ALC. Special challenges to technology implementation in the sustainment arena will be discussed in Chapter 5.

Innovation generally implies both risk and significant payoffs. Experience has shown that in fields such as new materials technology the total time from identification of the new technology to ultimate practical application usually ranges from 10 years to more than 20 years, even if appropriate and timely funding is available at every step (NRC, 1999b).

In the baseline process, the steps to application after Phase II are (1) incorporation of the technology into the AFRL core strategy and into its core

resource road maps and (2) the acceptance and funding of final transition and implementation by an ALC, a test center, or the acquisition programs of a particular DAC. Completing all of these steps is a formidable challenge for small businesses, which must rely heavily on the Air Force team's integrated transition strategy and its dedication to assisting with implementation issues.

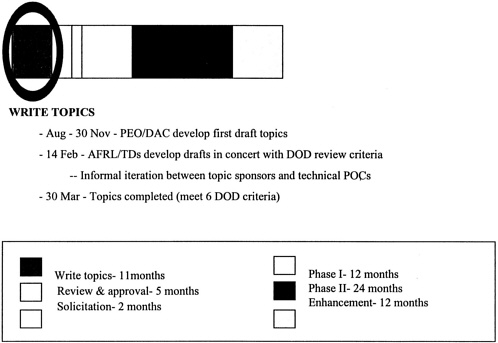

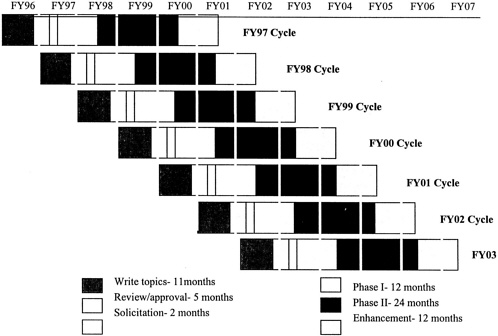

PROCESS METRICS AND TIME PHASING

As shown in Figure 3-2, the steps in the SBIR process, from topic definition by the Air Force to completion of a Phase II enhancement program by the small business, takes about 5 or 6 years. Significant additional funding and time may be required in Phase III before the technology can be implemented by the ultimate customer. In a given program area at any point in time, many SBIR programs are under way, each in a different phase ( Figure 3-3).

Under the original baseline SBIR program, the number of topics and the SBIR funding allocated to each AFRL directorate were proportional to the directorate's core S&T budget ( Table 3-3). The number of Phase I awards triggers Phase II funding requirements. Thus, the award ground rules mentioned above, the current statistics on active programs, and the level of directorate core S&T budgets provide the framework for the annual SBIR funding distribution decisions by the AFRL headquarters team.

Commercialization

Phase III is focused on commercialization, although this term means more than simply the commercial-sector application of Phase II program results. Commercialization is defined as the use of any non-SBIR funding that moves the technology a step closer to application. Thus, Air Force core S&T funding applied to further an SBIR-developed technology is considered commercialization.

If the Air Force or the military is the only customer for an SBIR technology, the market will obviously be severely limited, which raises business viability issues for small businesses. A dual-use market of military and commercial nonmilitary customers is much more desirable for both the Air Force and the small business. The Air Force can leverage the commercial market with the military market and vice versa. In addition, Air Force managers will be motivated to assist the small business in developing the nonmilitary applications of the technology. In fact, potential commercial success is an important criterion in the competitive SBIR contract award process.

Table 3-3 SBIR Topic Allocation: Baseline Process (FY00)

|

Directorate |

Number of Topics Allocated |

|

Munitions |

17 |

|

Air Vehicles |

18 |

|

Directed Energy |

21 |

|

Human Effectiveness |

24 |

|

Information |

28 |

|

Materials and Manufacturing |

28 |

|

Sensors |

28 |

|

Propulsion |

36 |

|

Space Vehicles |

40 |

|

TOTAL |

240 |

|

Table courtesy of Air Force Small Business Innovation Research Office. |

|

Even if they have not previously participated in an SBIR program, all companies must submit a Company Commercialization Report, which shows the quantitative results of the firm's prior SBIR projects. Since 1999, DOD has developed a commercialization achievement index (CAI) for firms with five or more Phase II awards prior to 1998; firms with fewer than five awards are given a CAI of N/A. The CAI, along with Phase II sales and investment information and explanatory material, is considered when evaluating proposals for their potential commercial applications.

For example, consider a firm that received 10 Phase II SBIR awards through 1997 and has an index of 95. If the firm's 10 awards were compared with a group of 10 DOD SBIR/STTR awards selected at random from the same time period, there would be a 95 percent chance that the commercialization resulting from the firm's awards would exceed the commercialization resulting from the randomly selected group. As a basis for this calculation, DOD maintains a database of Phase II projects awarded between 1984 and 1997. The data include sales revenue from new products and non-R&D services resulting from Phase II technologies; additional investments in technologies from sources other than the federal SBIR/STTR programs; and the percentage of additional investments that qualifies as hard investment.

PAST SBIR TOPICS ON AGING AIRCRAFT

A survey of the SBIR awards listed on the Web sites of the Air Force and Navy revealed that very few topics fell under the category “ aging aircraft.” However, many of the awards could be relevant to aging aircraft. In fact, the only way to determine the suitability of a topic for the aging aircraft category is by reading the abstract. Of the 1,800 abstracts of awards from 1993 to 1998 read by the committee, 108 were selected for the sampling study. Twenty-seven abstracts related to nondestructive testing methods, 18 related to joining issues for metals and composites, 24 called out methods of detecting corrosion and corrosion fatigue, 18 related to the development of materials for components that could be used in retrofitting aircraft, and 21 related to the development of processes and methods of coating/cleaning surfaces. Many abstracts related to new materials and processes to replace existing materials on various aircraft systems. Because many awards are made in generic topics such as coatings or nondestructive testing, they cannot be classified as being part of the aging aircraft program, although many are clearly suitable for aging aircraft systems.

Most of the FAA and NASA awards surveyed were related to the development of databases and the development of materials and models to understand fatigue behavior. A few topics were related to methods to corrosion prevention; many topics were related to nondestructive testing and techniques to develop new materials. A few FAA programs cited aging aircraft as the end application; no specified NASA awards were targeted at aging aircraft.

The committee attempted to determine levels of commercialization based on information on the Web sites of many of the companies that had received awards. Almost no useful information was derived from this effort, however. DOD and the Air Force collect data to arrive at the CAI for each company, but these data are not available for public use. Thus, the committee was unable to obtain actual sales numbers for specific companies and awards.

Findings and Recommendations

Finding. Solicitation for a Phase I topic, selection, award, submission of a Phase II proposal, award, and completion usually take 5 to 7 years. This is too long for the Air Force to wait for solutions to the most pressing problems of aging aircraft. Interaction and coordination among the government agencies on the topics selected for Phase II awards are minimal.

Recommendation. An interagency working group should be established by federal agencies that participate in the SBIR program to review all Phase II awards that are technically meritorious but have been rejected for lack of funding or other

reasons. To shorten the long gestation time and bring products to end users more quickly, a small portion of the SBIR budgets of defense agencies could be used to leverage funding with the civilian agency SBIR programs, especially in the areas of sensors, corrosion detection, and NDE. A secondary objective of the interagency group should be to partition the programs by subject for 2 or 3 years. For example, the Navy could fund projects on corrosion, the Air Force could fund projects on NDE, and the Army could fund projects on sensors.