2

The Magnitude of the Problem

Neurological, psychiatric, and developmental disorders exact a profound economic and personal toll in developing countries. Brain disorders affect the highest human faculties and, left untreated, can destroy a person's dignity, productivity, and autonomy. Yet despite their importance, these disorders have been largely ignored by public and private health systems in developing countries as compared with diseases that are better understood.[1]

Health policy on brain disorders has long been limited by the following misperceptions:

-

The illnesses are a problem in the developed but not the developing world.

-

They do not cause mortality.

-

They are not amenable to treatment.

-

They are too expensive to manage in developing countries.

This report seeks to counter each of these notions, the first of which is addressed in this chapter. The impact of brain disorders in developing countries is reviewed from several perspectives: the impact on nations and communities in terms of the overall disease burden due to death and disability, the impact on individuals and families due to lost time, lost productivity, stigmatization and discrimination, the reinforcing roles of poverty and gender inequality, and the lack of capacity to address these problems.

EFFECTS ON COMMUNITIES AND NATIONS

The Disease Burden

Prompted by estimates of the disease burden first published in 1993, health leaders have begun to recognize the major role of brain disorders in the overall burden of disease.[1,2 and 3] Governments and public health policy makers are starting to investigate the impact of this burden on communities and nations (see, for example, Box 2-1 on the 1999 report of the U.S. Surgeon General). Previous comparisons of the contribution of various disorders to the overall burden of disease were based most commonly on the cause of death alone, or sometimes years of life lost (YLLs) by cause. These comparisons dramatically underestimated the importance of brain disorders because these conditions tend to be chronic (not an acute cause of death) and therefore are rarely listed as the immediate cause of death in official records.[ 2,4] Yet depression, epilepsy, and other brain disorders often cause many years of serious disability. Brain disorders are responsible for at least 27 percent of all years lived with disability (YLDs) in developing countries.1 [5] With the exception of Sub-Saharan Africa, brain disorders are the leading contributors to YLDs in all regions of the world (see Table 2-1).[5]

In these calculations, the disability-adjusted life year, or DALY (a variant of the better known quality-adjusted life years, or QALY), assesses both disability and premature mortality in a single measure. In combining assessments of YLLs and YLDs, current DALY estimates highlight the significant contribution of brain disorders to the overall disease burden in developing countries (see Table 2-2).[5]

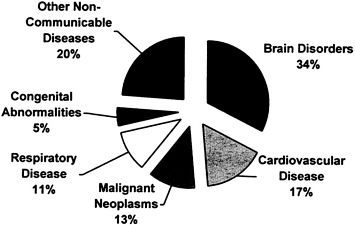

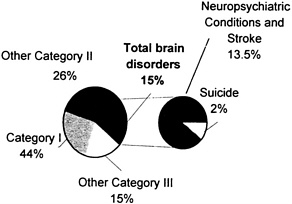

Absent data on most developmental disabilities and many adult neurological diseases,2 1998 estimates for brain disorders still show these conditions responsible for nearly 34 percent of all noncommunicable disease DALYs in developing countries (see Figure 2-1). Table 2-2 and Figure 2-2 show the contribution of brain disorders to all DALYs and mortality in developing countries. These conditions account for nearly 15 percent of DALYs and 12 percent of mortality among all disease categories. 3 [6]

Current DALY calculations for developing countries, however, reflect only a portion of the disease burden imposed by brain disorders. These sizable cal-

|

1 |

The percentage distribution of YLDs attributed to brain disorders is estimated using the 1990 data for neuropsychiatric conditions (25.5 percent), the cerebrovascular disease component of cardiovascular disease (approximately one percent), and the self-inflicted injury component of intentional injuries (approximately .5 percent). |

|

2 |

Data on such developmental disorders as mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and autism along with adult neurological conditions such as peripheral nerve disease and severe migraine were not accounted for in the estimates of the 1996 Global Burden of Disease study. |

|

3 |

Category I: Communicable disease, maternal and perinatal conditions and nutritional deficiencies; Category II: Non-communicable disease; and Category III: Injuries. |

|

BOX 2-1 Mental Health: A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General In 1999, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued its first Surgeon General's report on the topic of mental health. The report describes recent defining trends in research, treatments, care provision, and public opinion; reviews current knowledge on mental health care for children, adults, and the elderly; and charts a course for improving access to mental health services and effective treatment for mental disorders. About 10 percent of the U.S. adult population uses mental health services in the health sector in any given year, with another 5 percent seeking such services from social service agencies, schools, or religious or self-help groups. Yet despite the relative abundance of mental health care in the United States, as compared with most developing countries, critical gaps exist between those who need mental health care and those who receive service, as well as between optimally effective treatment and the care many people actually receive. Many of the findings in the Surgeon General's report concur with those in this volume. In the United States, as well as in much of the developing world, the stigma of having a mental illness represents a major barrier to treatment. A lack of awareness of the range of treatments for mental illness also hinders access to effective care. Financial barriers prevent many people from seeking mental health care, and capacity is limited by personnel shortages in several key fields. The two main findings of the Surgeon General's report are equally applicable in the developing world and in the United States:

Accordingly, several recommended courses of action based on these findings are also relevant in a broader context: to fight stigmatization by dispelling myths about mental illness and by increasing public awareness of the effectiveness of existing treatments; to establish effective, evidence-based community mental health services; to facilitate access to mental health care by increasing potential points of entry and reducing financial barriers; and to provide “culturally competent ” treatment that recognizes individual differences. While focusing on a subset of the brain disorders discussed in this volume, the Surgeon General's report emphasizes the central importance of the brain. “We recognize that the brain is the integrator of thought, emotion, behavior, and health,” states Surgeon General David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D, in his preface to the report. “Indeed, one of the foremost contributions of contemporary mental health research is the extent to which it has mended the destructive split between ‘physical' and ‘mental' health.” Source: [7] |

FIGURE 2-1 Non-communicable disease DALYs attributable to brain disorder, estimates for 1998.

FIGURE 2-2 Burden of brain disorders as a percentage of total disease burden in low- and middle-income countries, estimates for 1998.

Source:[6]

culations are surely lower-bound estimates of the true impact of brain disorders because they do not fully incorporate many of the known neurological and psychiatric sequelae of infectious, nutritional, genetic, and perinatal disorders, as well as environmental exposures. 4 Current data estimating the prevalence of brain disorders is considered inadequate because many patients in developing countries, particularly children with developmental disorders, do not receive medical care. In the United States, 12 to 18 percent of children are estimated to be disabled in some way.[ 8] Comparable measures would be expected to be substantially higher in developing countries, where children are exposed more frequently to infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies. While improvements in health care and sanitation are enabling more children to survive infancy in developing countries, concomitant efforts to reduce the occurrence of the number of disabled children is very likely to rise.[ 5]

Brain disorders in general are expected to play an increasingly important role in the disease burden of developing countries during the next two decades. Data for 1990 on the burden of disease in developing countries have been projected to 2020,[5] based on trends in cause-specific mortality rates, life expectancy, income per capita, human capital, smoking intensity, and HIV and tuberculosis infection rates. One projected calculation is that unipolar depression (the fourth leading cause of DALYs in 1990 for all age groups and the leading cause of DALYs among those aged 15 to 44) will become the leading cause among all age groups combined in 2020 (see Table 2-3, Table 2-4 through Table 2-5). This projected increase in DALYs attributable to depression reflects not only an aging population, but also recent increases in the rate of depression among younger people. Stroke, ranked as the tenth leading cause of DALYs in developing countries in 1990 (see Table 2-3), is projected to be the fifth leading cause in 2020 (see Table 2-5). Improvements in the reliability and validity of data and collection methods for brain disorders in developing countries may well reveal an even greater contribution to disease burden estimates.

It should be noted that in calculating disease burden estimates (e.g., YLDs and DALYs), the years of productive life lost as a result of disability are weighted according to expert opinion regarding the severity of a given disability. For example, the disability caused by major depression is estimated by panels of experts as approximately equivalent to that caused by blindness or paraplegia, while the disability caused by schizophrenia lies between that caused by paraplegia and quadriplegia.[4] The assumptions and judgments underlying DALY

|

4 |

Neurological and psychiatric sequelae not fully expressed in current DALY estimates include those caused by infectious disease (e.g.. cerebral malaria, HIV encephalopathy, and congenital rubella), nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iodine-deficiency syndrome and vitamin A blindness), perinatal conditions (e.g., birth trauma), genetic conditions (e.g., phenylketonuria and Duchenne's muscular dystrophy), and environmental exposures (e.g.. fetal alcohol syndrome and lead poisoning). |

estimates are complex and have been controversial. Some of the problems involve the relative value of living assigned to each age group, the comparative severity of different disabilities at different ages, diagnoses of diseases and their classifications, the presumption of disability weights as universal, and the accuracy and completeness of data sets for each country (see Appendix B for additional information on measurement limitations). The estimates will continue to be refined as stronger data and more widely tested assumptions become available. Meanwhile, current estimates using this indicator have provided the public health community with a valuable way to rank the impact of various diseases on health and to recognize the major role of diseases that cause a high level of disability.

TABLE 2-1 Percentage distribution of years lived with disability (YLDs) for specific causes, 1990

|

Region |

|||||||||||

|

Condition Group |

EME |

FSE |

IND |

CHN |

OAI |

SSA |

LAC |

MEC |

Developed |

Developing |

World |

|

All Causes |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

I. Communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions |

5.5 |

7.8 |

33.6 |

18.9 |

28.5 |

39.3 |

19.0 |

24.6 |

6.3 |

27.8 |

24.4 |

|

A. Infectious and parasitic diseases |

2.6 |

3.0 |

14.3 |

6.4 |

12.6 |

22.4 |

9.7 |

6.4 |

2.7 |

12.3 |

10.7 |

|

B. Respiratory infections |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.8 |

0.4 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

|

C. Maternal conditions |

0.6 |

1.9 |

4.7 |

1.9 |

4.0 |

5.8 |

2.7 |

5.0 |

1.1 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

|

D. Conditions arising during the perinatal period |

0.5 |

0.5 |

3.5 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

3.2 |

1.6 |

2.9 |

0.5 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

|

E. Nutritional deficiencies |

1.5 |

2.0 |

9.8 |

8.2 |

8.7 |

6.6 |

4.1 |

8.6 |

1.7 |

7.9 |

6.9 |

|

II. Noncommunicable diseases |

86.7 |

79.5 |

43.7 |

66.9 |

56.1 |

39.8 |

67.3 |

61.5 |

84.2 |

54.8 |

59.5 |

|

A. Malignant neoplasms |

3.8 |

2.5 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

3.3 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

|

B. Other neoplasms |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

1.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

|

C. Diabetes mellitus |

3.2 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

2.6 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

D. Endocrine disorders |

1.7 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

|

E. Neuro-psychiatric conditions |

47.2 |

37.6 |

20.9 |

30.7 |

28.5 |

16.3 |

34.6 |

25.4 |

43.9 |

25.5 |

28.5 |

|

F. Sense organ diseases |

0.2 |

0.2 |

3.4 |

2.0 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

|

G. Cardiovascular diseases |

6.2 |

7.1 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

1.6 |

2.4 |

3.8 |

6.5 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

|

H. Respiratory diseases |

6.1 |

7.1 |

5.0 |

14.0 |

4.7 |

6.6 |

6.1 |

7.8 |

6.5 |

7.7 |

7.5 |

|

I. Digestive diseases |

4.1 |

5.5 |

2.4 |

5.1 |

5.8 |

3.6 |

4.3 |

7.1 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

|

J. Genito-urinary diseases |

1.1 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

3.4 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

|

K. Musculo-skeletal diseases |

8.0 |

10.2 |

1.6 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

1.5 |

6.9 |

1.8 |

8.8 |

2.9 |

3.8 |

|

L. Congenital anomalies |

2.0 |

14.8 |

3.2 |

3.0 |

2.6 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

3.6 |

1.9 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

|

M.Oral conditions |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

2.0 |

0.6 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

|

III. Injuries |

7.9 |

12.7 |

22.8 |

14.2 |

15.4 |

20.9 |

13.6 |

13.9 |

9.5 |

17.4 |

16.1 |

|

A. Unintentional injuries |

7.1 |

10.7 |

22.4 |

12.9 |

14.6 |

16.3 |

12.3 |

10.0 |

8.3 |

15.4 |

14.3 |

|

B. Intentional injuries |

0.8 |

2.0 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

4.6 |

1.4 |

3.9 |

1.2 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

|

Note: EME = Established Market Economies; FSE = Formerly Socialist Economies of Europe; IND = India; CHN = China; OAI = Other Asia and Islands; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MEC = Middle Eastern Crescent Source: [5] |

|||||||||||

TABLE 2-2 Contribution of brain disorders to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and Mortality in low- and middle-income countries, estimates for 1998.

|

Condition |

DALYs (1,000s) |

% of Total DALYs |

Deaths (1,000s) |

% of Total Deaths |

|

All Disease |

1,274,259 |

45,897 |

||

|

Brain Disorders |

||||

|

Unipolar major depression |

51,217 |

4.02 |

0 |

0 |

|

Stroke |

36,407 |

2.86 |

4,213 |

9.20 |

|

Self-inflicted injuries |

19,095 |

1.50 |

818 |

1.80 |

|

Bipolar affective disorder |

14,421 |

1.13 |

15 |

0.03 |

|

Alcohol dependence |

13,553 |

1.06 |

42 |

0.09 |

|

Psychoses |

11,984 |

0.94 |

40 |

0.08 |

|

Obsessive compulsive disorders |

10,062 |

0.79 |

0 |

0 |

|

Alzheimer's disease and other dementias |

5,527 |

0.43 |

111 |

0.24 |

|

Drug dependency |

4,782 |

0.38 |

7 |

0.02 |

|

Panic disorders |

4,710 |

0.37 |

0 |

0 |

|

Epilepsy |

4,659 |

0.37 |

60 |

0.13 |

|

Post traumatic stress disorders |

1,896 |

0.15 |

0 |

0 |

|

Multiple sclerosis |

1308 |

0.10 |

20 |

0.04 |

|

Parkinson's disease |

621 |

0.05 |

30 |

0.07 |

|

Other neuropsychiatric disorders |

9,308 |

0.73 |

170 |

0.37 |

|

Total Brain Disorders |

189,550 |

14.90 |

5,526 |

12.00 |

|

Source: [6] |

||||

TABLE 2-3 Causes of DALYs (percentage total) in descending order, 1990

|

Developing Regions |

|||

|

Rank |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

% of Total |

|

All causes |

1,218,244 |

||

|

1 |

Lower respiratory infections |

110,506 |

9.1 |

|

2 |

Diarrheal diseases |

99,168 |

8.1 |

|

3 |

Conditions arising during the perinatal period |

89,193 |

7.3 |

|

4 |

Unipolar major depression |

41,031 |

3.4 |

|

5 |

Tuberculosis |

37,930 |

3.1 |

|

6 |

Measles |

36,498 |

3.0 |

|

7 |

Malaria |

31,705 |

2.6 |

|

8 |

Ischemic heart disease |

30,749 |

2.5 |

|

9 |

Congenital anomalies |

29,441 |

2.4 |

|

10 |

Cerebrovascular |

29,099 |

2.4 |

|

11 |

Road traffic accidents |

27,253 |

2.2 |

|

12 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

25,771 |

2.1 |

|

13 |

Falls |

24,232 |

2.0 |

|

14 |

Iron-deficiency anaemia |

23,465 |

1.9 |

|

15 |

Protein-energy malnutrition |

20,758 |

1.7 |

|

16 |

War |

18,868 |

1.6 |

|

17 |

Tetanus |

17,513 |

1.4 |

|

18 |

Violence |

15,632 |

1.3 |

|

19 |

Self-inflicted injuries |

15,199 |

1.3 |

|

20 |

Drownings |

14,819 |

1.2 |

|

Source: [5] |

|||

TABLE 2-4 Ten leading causes of DALYs at ages 15–44 years in developing regions, 1990

|

Both Sexes |

Males |

Females |

|||||||

|

Rank |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

|

Developing Regions |

|||||||||

|

All causes |

357,437 |

All causes |

180,211 |

All causes |

177,277 |

||||

|

1 |

Unipolar major depression |

35,398 |

9.9 |

Unipolar major depression |

12,658 |

7.0 |

Unipolar major depression |

22,740 |

12.8 |

|

2 |

Tuberculosis |

19,451 |

15.3 |

Road traffic accidents |

11,387 |

13.3 |

Tuberculosis |

8,703 |

17.7 |

|

3 |

Road traffic accidents |

14,321 |

19.4 |

Tuberculosis |

10,747 |

19.3 |

Iron-deficiency anemia |

7,135 |

21.8 |

|

4 |

War |

12,382 |

22.8 |

Violence |

9,844 |

19.3 |

Self-inflicted injuries |

6,526 |

25.5 |

|

5 |

Iron-deficiency anemia |

12,033 |

26.2 |

Alcohol use |

8,420 |

24.8 |

Obstructed labor |

6,033 |

28.9 |

|

6 |

Self-inflicted injuries |

12,004 |

29.5 |

War |

7,448 |

29.4 |

Chlamydia |

5,364 |

31.9 |

|

7 |

Violence |

11,448 |

32.7 |

Bipolar disorder |

5,601 |

36.7 |

Bipolar disorder |

5,347 |

34.9 |

|

8 |

Bipolar disorder |

10,948 |

35.8 |

Self-inflicted injuries |

5,478 |

39.7 |

Maternal sepsis |

5,226 |

37.8 |

|

9 |

Schizophrenia |

9,514 |

38.5 |

Schizophrenia |

5,068 |

42.5 |

War |

4,934 |

40.6 |

|

10 |

Alcohol use |

9,371 |

41.1 |

Iron-deficiency anemia |

4,898 |

45.3 |

Abortion |

4,856 |

43.4 |

|

Source: [5] |

|||||||||

TABLE 2-5 Ten leading causes of DALYs in developing regions in 2020 (baseline scenario)

|

Both Sexes |

Males |

Females |

|||||||

|

Rank |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

Disease or Injury |

DALYs (1,000s) |

Cumulative % |

|

Developing Regions |

|||||||||

|

All causes |

1,228,302 |

All causes |

701,018 |

All causes |

527,284 |

||||

|

1 |

Unipolar major depression |

68,037 |

5.6 |

Road traffic accidents |

44,907 |

6.4 |

Unipolar major depression |

44,652 |

8.5 |

|

2 |

Road traffic accidents |

64,388 |

10.8 |

Ischemic heart disease |

40,922 |

12.2 |

Ischemic heart disease |

23,406 |

12.9 |

|

3 |

Ischemic heart disease |

64,328 |

16.1 |

Cerebro-vascular disease |

31,252 |

16.7 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

22,817 |

17.2 |

|

4 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

52,677 |

20.4 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

29,859 |

21.0 |

Road traffic accidents |

20,266 |

21.1 |

|

5 |

Cerebrovascular disease |

51,518 |

24.6 |

Unipolar major depression |

24,185 |

24.4 |

Tuberculosis |

19,481 |

24.8 |

|

6 |

Tuberculosis |

42,364 |

28.0 |

Violence |

23,911 |

27.8 |

Lower respiratory infections |

19,382 |

28.4 |

|

7 |

Lower respiratory infections |

41,107 |

31.4 |

War |

23,285 |

31.1 |

War |

18,766 |

32.0 |

|

8 |

War |

40,190 |

34.6 |

Tuberculosis |

22,982 |

34.4 |

Diarrheal diseases |

16,379 |

35.2 |

|

9 |

Diarrheal diseases |

36,960 |

37.6 |

Lower respiratory |

22,341 |

37.6 |

HIV |

15,605 |

38.3 |

|

10 |

HIV |

33,962 |

40.4 |

Diarrheal disease |

20,581 |

40.5 |

Abortion |

4,856 |

41.3 |

|

Source:[5] |

|||||||||

EFFECTS ON INDIVIDUALS AND FAMILIES

Lost Productivity

Brain disorders interfere with the highest level of human functioning, greatly reducing productivity and social interaction.[9,10] Since these disabilities usually last for many years, they have profound emotional and financial effects on individuals and families.[ 11,12,13 and 14] These consequences are increased where treatment and support are not available.[15,16 and 17] A large economic cost is the lost productivity of workers whose disability prevents them from working at full capacity, if at all and those who die accidentally or by suicide as a result of brain disorders.[15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and 26] Additional economic costs result from the time and other resources required to care for a dependent family member.[11,15,19,20] Social costs of these disorders include the emotional burden of suffering a chronic disorder or caring for an affected family member, learning and developmental problems in children whose parents have brain disorders, and (in some cases) lifelong dependency.[18,21,22,27,28,29 and 30]

Stigma and Discrimination

The stigma and discrimination associated with disorders such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, and mental retardation increase the toll of illness for many people with brain disorders and their families. These individuals are often rejected by neighbors and the community, and as a result suffer loneliness and depression. The psychological effect of stigma is a general feeling of unease or of “not fitting in,” loss of confidence, increasing self-doubt leading to depreciated self-esteem, and a general alienation from society.[31] Moreover, the stigma is frequently irreversible,[32,33] so that even when the behavior or physical attributes disappear, an individual continues to be stigmatized by others and by their own self-perception.[34]

People with brain disorders and their families may also be subjected to other forms of social sanction, such as being excluded from community activities. One of the most damaging results of stigmatization is that affected individuals or those responsible for their care may not seek treatment, hoping to avoid the negative social consequences of diagnosis. This leads in turn to delayed or lost opportunities for treatment and recovery; underreporting of these conditions can also reduce efforts to develop appropriate strategies for prevention and treatment.[35]

Because the symptoms of brain disorders can be frightening to others or embarrassing to the afflicted, the social rejection of affected individuals takes several forms. Most frequently, rejection is manifested as lost opportunity for employment and a normal social life, sometimes for family members as well as

for patients. Many individuals affected by schizophrenia, for example, experience a vastly diminished quality of life because they are excluded from social events and social networks.[36] They often become homeless and spend years on the streets, in the criminal justice system, or in psychiatric hospitals. In all these situations they are exposed to abuse.[37,38]

Epilepsy carries a particularly severe stigma that is sustained by misconceptions, myths, and stereotypes.[9,39,40] In some communities, children who do not receive effective treatment for this disorder are removed from school; lacking a basic education, they may not be able to support themselves.[36,41] People in some African countries believe that saliva can spread epilepsy or that the “epileptic spirit” can be to transferred to anyone who witnesses a seizure. These misconceptions cause people to retreat in fear from someone having a seizure, leaving that person unprotected from open fires and other dangers they might encounter in cramped living conditions.[ 42,43 and 44]

Stigmatization and rejection can be reduced by providing factual information on the causes and treatment of brain disorders; by talking openly and respectfully about the disorder and its effects; and by providing and protecting access to appropriate health care.[45] Governments can reinforce these efforts with laws that protect people with brain disorders and their families from abusive practices and prevent discrimination in education, employment, housing, and other opportunities.

THE ROLES OF POVERTY AND GENDER INEQUALITY

Poverty and gender inequality underlie many key risk factors for disease generally; neurological, psychiatric, and developmental disorders are no exception. Indeed, these are the two risk factors of greatest salience for brain disorders in the developing world.

The Role of Poverty

A growing body of economic and epidemiological research suggests a reciprocal relationship between poverty and illness.[25,46] Rather than simply pointing to poverty as the root cause of ill health, decision makers—particularly in developing countries, where most people remain poor throughout their lives—should also begin to recognize illness as a major cause of poverty, and one that is amenable to public intervention.[46] The linkages between poverty and illness are likely to be as complex and variable as poverty itself. For example, in addition to suffering physical adversity and high mortality and morbidity resulting from poverty, many poor people in developing countries face the emotional hardship of living with gross income inequalities.[47,48 and 49]

Poverty-Associated Risk Factors for Brain Disorders

Several poverty-associated causes of ill health stand out as risk factors for brain disorders.

Unsafe and Unhygienic Living Conditions

Many of the world's poorest people live in extreme poverty in shantytowns and urban slums where they face squalor, corruption, drugs, violence, and predation. The relationship between such unhealthy physical environments and somatic disease is well established.[50,51,52 and 53] Given inadequate shelter, no control of sewage, limited access to potable water, and crowding, the poor are constantly exposed to infectious agents and environmental toxins that can cause epilepsy and developmental disabilities.[9,54,55 and 56] In unprotected living conditions, individuals suffering an epileptic seizure have a high mortality rate due, for example, to falling into an open fire or becoming lost in the bush.[9,39]

Hunger and Malnutrition

Several micronutrient deficiencies in mothers, when severe, can cause developmental disabilities in their infants (see Chapter 5).[57] Folic acid deficiency has been shown to cause spina bifida;[58] iodine deficiency can lead to cognitive deficits;[59] vitamin A deficiency can cause blindness [60] and increase a child's vulnerability to severe infections.[61] Anxiety and depression have also been associated with chronic hunger,[ 62] while high infant and child mortality among families living in extreme poverty can have significant psycho-social effects on parents and other family members.[63]

Inadequate Access to Health Care

Poor people in the developing world rarely receive preventive care or effective treatment for brain disorders. In Brazil, for example, poverty and lack of education have been shown to reduce access to prevention and treatment of stroke.[64] In Zambia, risk factors for stroke, such as hypertension and diabetes, frequently go undetected and therefore untreated because caregivers lack basic diagnostic technology.[34] Similarly, untreated substance abuse, epilepsy, schizophrenia, and depression can lead to chronic disability or death. In India, patients with psychiatric disorders may receive a combination of vitamin injections, herbal medicines, and benzodiazepines from tradtional healers,[65] the total cost of which can exceed that of effective biomedical care.[66,67, 68 and 69]

Lack of Educational and Employment Opportunities

Poverty is commonly associated with a substandard education. It is also associated with decreased cognitive potential,[70,71] poor nutrition, and lack of home support for educational achievement. The all-too-frequent result is inadequate achievement and outcomes in school, and lifelong limitations of employment opportunities.[ 72,73,74 and 75]

Each of these poverty-related factors tends to exacerbate the impact of the others.[70] The illnesses—including brain disorders—to which these factors predispose people can in turn lead to depressed economic circumstances, thus creating a vicious cycle of illness and economic deprivation.[14] Brain disorders interfere with effective functioning at school, work, and home, causing social and economic hardship. Substance abuse, learning disabilities, and schizophrenia, for example, can prevent students from completing their education, thereby limiting their ability to find employment and support themselves.[72 and 73]

Beyond the aforementioned general threats to brain health, poverty has been shown to pose specific risks. Poverty can profoundly affect early development, beginning with the prenatal period and continuing through early childhood. Poverty-related factors are associated with increased neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates; developmental disorders; and injuries from accidents, abuse, or neglect.[76] When health and housing are inadequate, infection and malnutrition often limit a child's growth and development.[77] Living in a poor family has been shown to be the single strongest predictor for developmental disabilities in preschoolers, outweighing the role of maternal age and educational attainment.[71]

Malnutrition, physical illness, exposure to toxins such as alcohol and lead, perinatal injury, and lack of educational and social stimulation have been shown to adversely affect the cerebral mechanism of attention, which has been identified as a major source of cognitive deficits in school children.[71] Similar observations have been made in the United States, where perinatal complications, exposure to lead, and lack of cognitive stimulation have been found to account for diminished cognitive function in children of low socioeconomic status.[73] Malnutrition, along with perinatal complications and infection, has been associated with increased risk for epilepsy among Indian children.[78] Food deprivation leading to low birth weight or slow weight gains during the first year has been suggested as contributing to stroke risk during adulthood if food later becomes plentiful.[79,80]

Schizophrenia and other severe mental illness can lead to unemployment, family breakdown, and homelessness in a wide range of settings.[ 81,82 and 83] Research in the developed world indicates that people with schizophrenia experience a downward socioeconomic drift,[82] a trend that is probably echoed in developing countries.

Depression, alcohol dependence, stroke, and epilepsy rank among the leading causes of disability worldwide and share disabling consequences, such as stigmatization, suicide, violence, family disruption, and long-term disability.[84,85] A combined analysis of five recent surveys from Brazil, Zimbabwe, India, and Chile reveals a consistent and significant association between low income and risk of one of these disorders.[48,64] The data also suggest associations between indicators of impoverishment, such as hunger or indebtedness, and these disorders. In Indonesia, lower rates of depression and other common mental disorders were observed in individuals with higher levels of education, access to amenities such as electricity, and television ownership. This association applied to entire communities as well as to individuals: the least-developed villages surveyed had common mental disorder rates of 28 percent, compared with 13 percent in the most-developed villages.[86] Similar findings have been made in other countries.[83] Other studies have demonstrated a higher risk for common mental disorders and suicide among unemployed persons,[15,84,87] those with lower incomes,[87,88] and those with a lower standard of living.[81,89]

The Role of Gender Inequality

For many years, public health has equated women's health with reproductive and child health, and rarely considered women's well-being for its own sake.[48] This lack of attention appears particularly egregious in the case of brain disorders, given that women make up a disproportionate share of those living in poverty and also face gender inequalities—both of which, as noted earlier, are exacerbating factors in the development of these disorders.

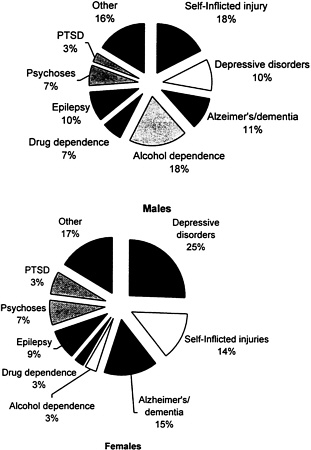

Studies of psychiatric disorders across cultures reveal that depression is more prevalent in women (see Figure 2-3).[90,91] One large epidemiological study in China showed that depression was nine times higher in women than in men.[92] In addition to the higher risks to their health, women have in the past also received inferior care and, as a result, suffered more severe consequences than men with similar disorders. Although schizophrenia is diagnosed more frequently in women than in men in China, Chinese women occupy fewer psychiatric hospital beds and generally receive less assistance than men.[93] A few studies conducted in developing countries indicate that the situation is improving.[94,95 and 96]

Similarly, the consequences of having epilepsy appear to be more severe for African women than for African men. They are less likely to receive treatment for their illness, are less likely to marry, and are often rejected by their families. To support themselves, many African females with epilepsy become prostitutes and thereby become vulnerable to sexually transmitted disease.[39]

FIGURE 2-3: Mental Health Problems of Males and Females Worldwide Percentages of DALYs Lost

Note: DALY = disability-adjusted life years; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

Source: [1]

The conclusions of several studies describing the disproportionately severe effects of depression and other psychiatric disorders on women in the developing world enumerate the factors found to contribute to women's vulnerability: unequal status, not being valued by husbands or society, dependence on husbands, marital stress, low education, social isolation, economic deprivation, multiple family responsibilities, hard physical labor, lack of employment, and employment in a low-income job.[88,90,97,98 and 99] The evidence points in particular to a link between the latter two factors and psychiatric disorders. A classic study in London, for example, found depression to be more severe for working-class than middle-class women.[98] In low-income societies, a woman's workday is an exhausting dawn-to-dusk routine that causes frustration, chronic fatigue, and demoralization, and leads to feelings of powerlessness and lack of opportunity.[1,88] Considerable evidence links these stressful feelings, experienced by many more women than men, with the onset of depression.[89,98,100,101,102 and 103] Additional stresses arise for rural women in developing countries when men migrate to urban areas and leave wives to do the farming as well as other chores; in rural China this practice has led to high suicide rates among overburdened young wives.[104] Biological differences between men and women may also contribute to differences in the prevalence of depression among the sexes.[ 99,105,106] This issue is separate from gender inequality, though biology may serve to reinforce societal causes of high depression rates among women.

Many of women's reproductive health issues also have significant implications for mental health. These issues, which include childbirth, adverse maternal outcomes (stillbirths and abortions), premarital pregnancies in adolescents, menopause, and infertility, challenge women's emotions and coping abilities.[107] For example, when couples fail to conceive, women tend to take the brunt of the disappointment and blame.[108] In India, infertility and failure to produce a male child have been linked to wife battering and female suicide.[108,109] The effects of women's reproductive health on their mental health include the following.

Postnatal Depression

Many women suffer depression during the period immediately following childbirth.[99,109,110 and 111] Although limited, the literature on postnatal depression (PND) in developing countries suggests that it can be detected in 10 to 36 percent of new mothers.[112,113,114 and 115] The detection of PND is of great public health interest because of its profound impact on maternal and child health. Compelling evidence implicates PND in a range of adverse cognitive and emotional outcomes in children.[95] One recent study recorded a high prevalence of postnatal depression and demonstrated its adverse impact on the relationship between mother and infant.[96] Although the majority of cases of PND are self-limiting, the untreated disorder may take up to a year to resolve.[109] Interventions such as nondirective counseling can prevent the adverse outcomes associated with PND.[97]

Rape and Sexual Violence

The consequences of rape and sexual violence can include emotional trauma, depression, physical injury, pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS, and death.[116,117,118 and 119] Involuntary prostitution has occurred more frequently in recent years through the luring of women into sexual slavery with promises of marriage or work. Female genital mutilation, forced sterilization or involuntary abortion, and partners who demand unprotected sex also contribute to dire mental health consequences.[120,121 and 122]

HIV/AIDS

People with HIV are at increased risk for depression for a variety of reasons: the stigma and discrimination associated with the disorder, the knowledge that they are likely to die prematurely of AIDS, the discovery that other family members may also have the disease, and the direct and indirect effects of HIV on the brain, as well as the effects of secondary neoplastic and infectious diseases.[123,124] Evidence also suggests that caregivers for people with HIV/AIDS, who tend to be women, suffer mental and physical health problems, particularly depression.[125] The impact of HIV/AIDS on women's mental health is likely to be enormous in countries such as Zimbabwe, where 30 percent of pregnant women attending antenatal health clinics were found to be HIV-positive.[126] In such situations, women must cope not only with illness in their male partners but also with their own failing health and that of their children.

Domestic Violence

Women are overwhelmingly the targets of domestic violence. This is a largely hidden problem, but routine battering is estimated to affect 25 to 65 percent of women across diverse cultures, including India,[ 88] Sri Lanka,[127] Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea,[128] Thailand, and Mexico.[129] South American countries have a particularly high rate of alcohol-related spouse abuse.[1] Domestic violence resulting in death occurs increasingly through dowry deaths of brides in India and female infanticide in India and China. Female victims of violence are likely to suffer disabling and long-lasting health effects, such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as dissociation disorders, somatization, sexual dysfunction, and self-harm behavior.[116,130,131 and 132] Elderly women in poor societies are often vulnerable to personal abuse, isolation, suicide, and the stigma associated with accusations of witchcraft, particularly when issues of land ownership are disputed.[ 133,134]

While the associations between gender and mental health justifiably focus on the substantial vulnerability of women in the developing world, men are more commonly dependent on alcohol and drugs than are women (see Figure 2-3). Substance abuse and dependence have been linked to premature mortality

(from cirrhosis, accidents, lung cancer, and other associated causes), risky behavior (with consequences such as hepatitis B and HIV infection), and greater exposure to violence and injuries.[130,135,136] Although depression occurs more frequently in women, men complete a greater proportion of suicides,5 a statistic that appears to reflect the higher rates of substance abuse among men and perhaps also wider access to the most effective means of suicide, such as guns.[138,139 and 140] Men are also at higher risk than women for stroke.[141,142]

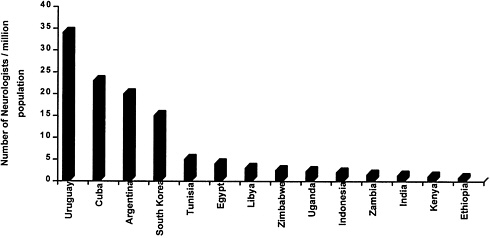

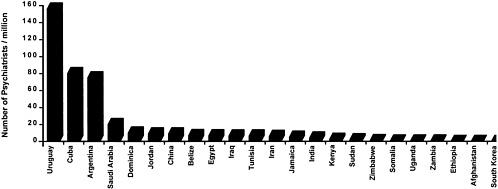

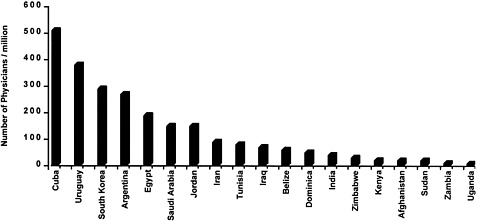

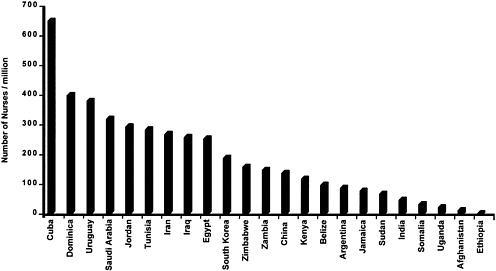

CAPACITY TO ADDRESS BRAIN DISORDERS

In many developing countries, health care for brain disorders is in even shorter supply than health care for other important diseases. Figure 2-4, Figure 2-5, Figure 2-6 through Figure 2-7 compare the numbers of neurologists, psychiatrists, general physicians, and nurses per capita for several developing countries. In India, for example, there are about 3,000 psychiatrists and 565 neurologists to serve a billion people,[143,144] while in Zimbabwe there are 10 psychiatrists and 29 neurologists to serve 11 million people.[145,146] Specialists in the prevention and management of pediatric brain disorders are even more scarce, especially as compared with the large pediatric population in developing countries. In addition, most of these specialists are located in cities, leaving rural populations unserved. Among the larger number of general physicians in the developing world, only a minority are experienced in the care of brain disorders, and they tend to be more familiar with hospital than with primary care presentation of cases.

With human resources being so limited, policy makers in the developing world face difficult choices on how to allocate these and equally limited financial resources to best meet health care needs. Since many brain disorders impair cognitive function, an attempt must be made to estimate the costs and benefits associated with all aspects of care, as well as lost wages and the time and financial commitments borne by family members (see Chapter 4). Cost-effectiveness data from developed countries, along with limited evidence from developing countries, reveal certain cost-effective interventions (see Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9 through Chapter 10). Demonstration projects and operational research should be conducted to measure their sustainability and impact on brain disorders in a range of low-income communities.

|

5 |

Except in China, where women commit suicide more often than men.[ 137] |

CONCLUSION

To compete in international markets and to build stronger national and local infrastructures, developing countries must produce well-educated workers, a process that begins with prenatal care and continues through the adult years of employment. Since many brain disorders interfere not only with health but also with education, they present an especially insidious limitation to developing economies. The consequences for a country's development of ignoring the burden imposed by these disorders are clearly large, and growing larger.

These disorders create, special problems for developing countries not only because of the scarcity of resources available to address them but also because of their mutually reinforcing relationship with poverty. Poor women bear an even heavier burden than poor men as a result of several gender-specific risk factors, many of which are preventable. The implementation of cost-effective interventions can help to reduce the impact of these disorders and break this debilitating cycle. Thus, poverty and gender inequality, which contribute greatly to the burden of brain disorders in developing countries, should be viewed as a target of the recommendations made in this report.

Despite the increasingly significant contribution of brain disorders to disease burden, these conditions are largely missing from the international health agenda.[1] Stigma, discrimination, economic and gender inequalities, and lack of capacity for addressing these add to their burden in developing countries. Recognizing the importance of brain disorders is the first step toward reducing this burden. The process can be further advanced through increased understanding of the social and economic effects of brain disorders as well as through provision of cost-effective care.

REFERENCES

1. R. Desjarlais, L. Eisenberg, B. Good, and A. Kleinman. World Mental Health. Oxford University Press: New York, 1995.

2. World Bank. World Development Report: Investing in Health Research Development World Bank: Geneva, 1993.

3. N. Sartorius, T. B. Ustun, J. A. Costa e Silva, D. Goldberg, Y. Lecrubier, J. Ormel, et al. An international study of psychological problems in primary care. Preliminary report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Project on “Psychological Problems in General Health Care.” Archives of General Psychiatry Oct,50(10):819–824, 1993.

4. T. B. Ustun. The Global Burden of Mental Disorders. American Journal of Public Health Sept. 89(9), 1999.

5. C. Murray and A. Lopez, eds. The Global Burden of Disease. The Harvard Press: Boston, 1996.

6. WHO (World Health Organization). The World Heath Report. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1999.

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General-Executive Summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health : Rockville, MD, 1999.

8. T.W. Langfitt. Presentation to IOM Committee on Neurological, Psychiatric, and Developmental Disorders in the Developing World, 2000.

9. K. Kahn and S.M. Tollman. Stroke in rural south Africa: Contributing to the little known about a big problem. South Africa Medicine Journal 89,63–65, 1999.

10. D. Kebede, A. Alem, T. Shibre, A. Fekadu, D. Fekadu, A. Negash et al. The Bitajira-Ethiopia study of the course and outcome of schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. I. Description of study settings, methods and cases. Unpublished manuscript, 1999.

11. R. Goeree, B.J. O'Brien, P. Goering, G. Blackhouse, K. Agro, A. Rhodes, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Jun;44(5),464–472, 1999.

12. M. Zhang, K.M. Rost, J.C. Fortney, and G. R. Smith. A community study of depression treatment and employment earnings Psychiatric Service Sep;50(9),1209–1213, 1999.

13. L.L. Judd, M.P. Paulus, K.B. Wells, and M.H. Rapaport. Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptom and major depression in a sample of the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry Nov;153(11),1411–1417, 1996.

14. J. Westermeyer. Economic losses associated with chronic mental disorder in a developing country. British Journal of Psychiatry 144,475–481, 1984.

15. S.V. Thomas. Money matters in epilepsy. Neurology India Dec;48(4),322–329, 2000.

16. G.E. Simon, D. Revicki, J. Heiligenstein, L. Grothaus, M. Von Korff, W.J. Katon, and T.R. Hylan. Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry May-Jun;22(3),153–162, 2000.

17. W. Mak, J.K. Fong, R. T. Cheung, and S. L. Ho. Cost of epilepsy in Hong Kong: Experience from a regional hospital Seizure Dec;8(8),456–464, 1999.

18. Health-related quality of life among persons with epilepsy—Texas, 1998. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report Jan 19;50(2),24–26, 35, 2001.

19. L.M. Brass. The impact of cerebrovascular disease. Diabetes, Obestiy and Metabolism Nov;2 Supplement 2,S6–S10, 2000.

20. C. S. Dewa and E. Lin. Chronic physical illness, psychiatric disorder and disability in the workplace. Social Science and Medicine Jul;51(1),41–50, 2000.

21. P.E. Greenberg, T. Sisitsky, R.C. Kessler, S.N. Finkelstein, E.R. Berndt, J.R. Davidson, et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry Jul;60(7),427–435, 1999.

22. R. J. Wyatt and I. Henter. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology Aug;30(5),213–219, 1995.

23. P. Kind and J. Sorensen. The costs of depression. International Clinic of Psychopharmacology Jan;7(3-4),191–195, 1993.

24. A. Stoudemire, R. Frank, N. Hedemark, M. Kamlet, and D. Blazer. The economic burden of depression. General Hospital Psychiatry Nov;8(6),387–394, 1986.

25. D.R. Gwatkin and M. Guillot. The Burden of Disease Among the Global Poor. World Bank: Washington D.C., 2000.

26. M. Bartley. Unemployment and ill health: understanding the relationship. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 48,333–337, 1994.

27. J.E. Ritsher, V. Warner, J.G. Johnson, and B.P. Dohrenwend. Inter-generational longitudinal study of social class and depression: A test of social causation and social selection models. British Journal of Psychiatry Apr;178(40, S84–S90, 2001.

28. S. Soepatmi. Developmental outcomes of children of mothers dependent on heroin or heroin/methadone during pregnancy. Acta Paediatrica Nov; 404 (Supplement),36–39, 1994.

29. B. Maughan and G. McCarthy. Childhood adversities and psychosocial disorders. British Medical Bulletin Jan;53(1),156–169, 1997.

30. B.T. Zima, K.B. Wells, B. Benjamin, and N. Duan. Mental health problems among homeless mothers: Relationship to service use and child mental heatlh problems. Archives of General Psychiatry Apr;53(4),332–338, 1996.

31. G. Scambler and A. Hopkins. Being epileptic; coming to terms with stigma. Social Health and Fitness 8,26–43, 1986.

32. E. Friedson. Profession of Medicine: A study of sociology of applied knowledge Russell Sage: New York, 1970.

33. G.L. Albrecht, V.G. Walker, and J. A. Levy. Social distance from the stigmatized: A test of two theories. Social Science and Medicine 16(14),1319–1327, 1982.

34. G.L. Birbeck. Barriers to care for patients with neurologic disease in rural Zambia Archives of Neurology Mar 57(3),414–417, 2000.

35. A. Jablensky, J. McGrath, H. Herrman, D. Castle, O. Gureje, M. Evans, et al. Psychotic disorders in urban areas: An overview of the Study on Low Prevalence Disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34,221–236, 2000.

36. R. Padmavathi, S. Rajkumar, N. Kumar, A. Manoharan, and S. Kamath. Prevalence of schizophrenia in an urban community in Madras. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 31,233–239, 1987.

37. B.S. Singhal. Neurology in developing countries. Archives of Neurology 55,1019–1021, 1998.

38. M. Gourie-Devi, P. Satishchandra, and G. Gururaj. National workshop on public health aspects of epilepsy. Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology 2,43–48, 1999.

39. L. Jilek-Aall, W. Jilek, J. Kaaya, L. Mkombachepa, and K. Hillary. Psychosocial study of epilepsy in Africa. Social Science and Medicine 45,783–795, 1997.

40. S.D. Shorvon and P.J. Farmer. Epilepsy in developing countries: a review of epidemiological, sociocultural, and treatment aspects. Epilepsia 29(1),S36–S54, 1988.

41. P. Jallon. Epilepsy in developing countries. Epilepsia 38(10),1143–1151, 1997.

42. K. K. Hampton, R.C. Peatfield, T. Pullar, H.J. Bodansky, C. Walton, and M. Feely. Burns because of epilepsy. British Medical Journal 296(11),16–17, 1988.

43. H.T. Rwiza, I. Mtega, and W.B. P. Matiya. The clinical and social characteristics of epilepsy patients in the Ulanga District, Tanzania. Journal of Epilepsy 5,162–169, 1993.

44. M. Berrocal. Burns and epilepsy. Acta Chirurgiae Plasticae 39(1),22–27, 1997.

45. L. Jilek-Aall. Morbus sacar in Africa: Some religious aspects of epilepsy in traditional cultures. Epilepsia Mar;40(3),382–386, 1999.

46. World Bank. World Development Report. World Bank: Washington D.C., 2000.

47. M. Sundar. Suicide in farmers in India (letter). British Journal of Psychiatry 175,585–586, 1999.

48. V. Patel, R. Araya, M.S. Lima, A. Ludermir, and C. Todd. Women, Poverty and Common Mental Disorders in four restructuring societies. Social Science and Medicine 49,1461–1471, 1999.

49. D. Sinha. Psychological concomitants of poverty and their implications for education. In: Perspectives on Educating the Poor. Atal, Y. ed. Abhinav Publications: New Delhi, pp. 57–118, 1997.

50. G. Halliday, S. Banerjee, M. Philpot, and A. Macdonald. Community study of people who live in squalor. Lancet Mar 11;355(9207),882–886, 2000.

51. M. Olfson, S. Shea, A. Feder, M. Fuentes, Y. Nomura, M. Gameroff, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder in an urban general medicine practice. Archives of Family Medicine Sep–Oct;9(9),876–883, 2000.

52. G.R. Glover, M. Leese, and P. McCrone. More severe mental illness is more concentrated in deprived areas British Journal of Psychiatry Dec; 175,544–548, 1999.

53. H. Freeman. Mental health and the environment. British Journal of Psychiatry Feb;132,113–124, 1978.

54. D.K. Pal, A. Carpio, and J.W. Sander. Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy in developing countries. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry Feb;68(2),137–143, 2000.

55. A.J. McMichael. The urban environment and health in a world of increasing globalization: issues for developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(9),1117–1126, 2000.

56. S. Tong, Y.E. von Schirnding, and T. Prapamontol. Environmental lead exposure: A public health problem of global dimensions Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(9),1068–1077, 2000.

57. R. Perez-Escamilla and E. Pollitt. Causes and consequences of intrauterine growth retardation in Latin America. Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization 26(2),128–147, 1992.

58. N.M.J. Van der Put, F. Gabreels, E.M.B. Stevens, J.A.N. Smeitink, F. J. M. Trijbels, and T.K. A. P. Eskes, et al. A second common mutation in the methylenetetra hydrofolate reductase gene: An additional risk factor for neural-tube-defects? American Journal of Human Genetics 62,1044–1051, 1998.

59. B. Lozoff, E. Jimenez, and A. W. Wolf. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine 325(10),687–694, 1991.

60. WHO (World Health Organization). ICD-10:International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1992.

61. A. Sommer and K. P. West, Jr. The duration of the effect of Vitamin A supplementation. American Journal of Public Health. Mar; 87(3),467–469, 1997.

62. N. Scheper-Hughes. The madness of hunger: Sickness, delirium, and human needs. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry Dec;12(4),429–458, 1988.

63. N. Scheper-Hughes. Death Without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. University of California: Berkeley, p. 547, 1992.

64. B. A. de Santana, M. M. Fukujima, and R.M. de Oliveiria. Socioeconomic characteristics of patients with stroke. Arq Neuropsichiatr [Portugese] 54(3),428–432, 1996.

65. V. Patel, J. Perieira, L. Coutinho, R. Fernandes, J. Fernandes, and A. Mann. Psychological disorder and disability in primary care attenders in Goa, India. British Journal of Psychiatry 171,533–536, 1998.

66. V. Patel, E. Simunyu, and F. Gwanzura. The pathways to primary mental health care in Harare, Zimbabwe. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32,97–103, 1997.

67. K. Saeed, R. Gater, A. Hussain, and M. Mubbashar. The prevalence, classification and treatment of mental disorders among attenders of native faith healers in rural Pakistan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology Oct;35(10),480–485, 2000.

68. G.L. Birbeck. Seizures in rural Zambia. Epilepsia Mar;41(3),277–281, 2000.

69. A. Singh and A. Kaur. Epilepsy in rural Haryana–Prevalence and treatment seeking behaviour. Journal of the Indian Medical Association Feb;95(2),37–39, 1997.

70. A. F. Mirsky. Perils and pitfalls on the path to normal potential: The role of impaired attention. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology 17(4),481–498, 1995.

71. J.E. Miller. Developmental screening scores among preschool-aged children: The roles of poverty and child health. Journal of Urban Health 75(1),135–152, 1998.

72. M. Haq and K. Haq. Human Development in South Asia: The Education Challenge. Oxford University Press: Karachi, 1999.

73. V. McLoyd. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist 53(2),185–204, 1998.

74. I. Heath, A. Haines, Z. Malenica, J. Oulton, Z. Liepando, D. Kaseje, et al. Joining together to combat poverty. Croatian Medical Journal Online (http://www.vms.cmj.2000/410104.htm), 2000.

75. G. Alvarez. The neurology of poverty. Social Science and Medicine 16(9),945–950, 1982.

76. J. L. Aber, N. G. Bennett, D. C. Conley, and J. Li. The effects of poverty on children's health and development. Annual Review of Public Health 18,468–483, 1997.

77. E. Pollitt. Poverty and child development: Relevance of research in developing countries to the United States. Child Development 65,283–295, 1994.

78. R. J. Hackett, L. Hackett, and P. Bhakta. The prevalence and associated factors of epilepsy in children in Calicut District, Kerala, India. Acta Paediatrica 86(11),1257–1260, 1997.

79. D.J.P. Barker and C. Osmond. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. In: D.J.P. Barker, ed. Fetal and Infant Origins of Adult Disease. British Medical Journal: London, 1992.

80. T. A. Pearson. Cardiovascular disease in developing countries: Myths, realities, and opportunities. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy 13,95–104, 1999.

81. G. Lewis, P. Bebbington, T.S. Brugha, M. Farrell, B. Gill, R. Jenkins, et al. Socioeconomic status, standard of living and neurotic disorder. Lancet 352,605–609, 1998.

82. B.P. Dohrenwend, I. Levav, P.E. Strout, S. Schwartz, S. Naveh, B.C. Link et al. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: The causation-selection issue. Science Feb 21;255(5047) 946–952, 1992.

83. S. Weich and G. Lewis. Poverty, unemployment and the common mental disorders: A population-based cohort study. British Medical Journal 317,115–119, 1998.

84. G. Lewis and A. Sloggett. Suicide, deprivation and unemployment: Record linkage study. British Medical Journal 317,1283–1286, 1998.

85. S. V. Thomas and V. B. Bindu. Psychosocial and economic problems of parents of children with epilepsy Seizure 8,66–69, 1999.

86. E. Bahar, A.S. Henderson, and A.J. Mackinnon. An epidemiological study of mental health and socioeconomic conditions in Sumatera, Indoniesia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 85(4),257–263, 1992.

87. D.J. Gunnell, T.J. Peters, R.M. Kammerling, and R.J. Brooks. Relation between parasuicide, suicide, psychiatric admissions, and socioeconomic deprivation. British Medical Journal 311,226–230, 1995.

88. S. Jejeebhoy. Wife-beating in rural India: A husband's right? Evidence from survey data. Economic and Political Weekly (3),855–862, 1998.

89. D. B. Mumford, K. Saeed, I. Ahmad, S. Latif, and M. Mubbashar. Stress and psychiatric disorder in rural Punjab: A community study British Journal of Psychiatry 170,473–478, 1997.

90. J. Broadhead and M. Abas. Life events and difficulties and the onset of depression among women in a low-income urban setting in Zimbabwe. Psychological Medicine 28,29–38, 1998.

91. J. Cooper and N. Sartorius, eds. Mental Disorder in China, Gaskell: London, 1996.

92. M. Gibbon. The use of romal and informal health care by female adolescents in eastern Nepal. Health Care for Women International Jul–Aug;19(4),343–360, 1998.

93. R. Warner. Recovery from Schizophrenia: Psychiatry and Political Economy. Routledge and Kegan Paul: London:, 1985.

94. C.E. Okojie. Gender inequalities of health in the Third World. Social Science and Medicine 39(9),1237–1247, 1994.

95. S. Malik. Women and mental health. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 35,3–10, 1993.

96. V. Pearson. Goods on which one loses: Women and Mental Health in China. Social Science and Medicine 45,1159–1173, 1995.

97. B. Davar. The Mental Health of Indian Women: A Feminist Agenda. Sage: New Delhi, 1999.

98. G. W. Brown and T.O. Harris. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. Free Press: New York, 1978.

99. S. Guatam. Post partum psychiatric syndromes: Are they biologically determined? Indian Journal of Psychiatry 31,31–42, 1989.

100. G.W. Brown, M. Bhrolchain, and T. Harris. Social class and psychiatric disturbance among women in an urban population. Sociology 9,225–257, 1975.

101. V. Makosky. Sources of stress: events or conditions? In: Lives in Stress: Women and Depression. Belle, D., ed. Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, California, pp.35–53, 1982.

102. I. Blue, M.E. Bucci, S. Jaswal, A. Ludermir, and T. Harpham. The mental health of low-income urban women: case studies form Bombay, India; Olinda, Brazil; and Santaigo, Chile. In: Urbanization and Mental Health in Developing Countries, Harpham, T., Blue, T., eds. Avebury: Aldershot, pp.75–101, 1995.

103. R. Kessler. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology 48,191–214, 1997.

104. A. Kleinman, J. Kleinman, and L. Sing. The Transforming of Social Experience in Chinese Society. Special Issue of Culture, Medicine, and Society 23(1),1–156, 1999.

105. V. Hendrick, L.L. Altshuler, and R. Suri. Hormonal changes in the postpartum and implications for postpartum depression. Psychosomatics Mar–Apr;39(2),93–101, 1998.

106. P.J. Lucassen, F. J. Tilders, A. Salehi, and D. F. Swaab. Neuropeptides vasopressin (AVP), oxytocin (OXT) and corticotropin-realesing hormone (CRH) in the human hypothalamus: Activity changes in aging, Alzheimer's disease and depression. Aging (Milano) 9(4),48–50, 1997.

107. L. Dennerstein, J. Astbury, and C. Morse. Psychosocial and Mental Health Aspects of Women's Health. World Health Organization : Geneva, 1993.

108. M.C. Inhorn. Kabsa (a.k.a. mushahara) and threatened fertility in Eygpt. Social Science and Medicine Aug;39(4),487–505, 1994.

109. R. Kumar. Postnatal mental illness: A transcultural perspective. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Nov;29(6),250–264, 1994.

110. S. Nhitawa, V. Patel, and S.W. Acuda. Predicting postnatal mental disorder with a screening questionnaire: A prospective cohort study from a developing country. Journal of Epidemiology and Community of Health 52,262–266, 1998.

111. Y.A. Aderibigbe, O. Gureje, and O. Omigbodun. Postnatal emotional disorders in Nigerian women. British Journal of Psychiatry 163,645–650, 1993.

112. M. E. Reichenheim and T. Harpham. Maternal mental health in a squatter settlement in Rio de Janeiro British Journal of Psychiatry 159,683–690, 1991.

113. L. Murray and P. Cooper. The impact of postpartum depression on child development. Internal Review of Psychiatry 8,55–63, 1997.

114. P. Cooper, M. Tomlinson, L. Swartz, M. Woolgar, L. Murray, and C. Molteno. Postpartum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. British Journal of Psychiatry 175,554–558, 1999.

115. J. Holden. The role of health visitors in postnatal depression. International Review of Psychiatry 8,79–86, 1996.

116. R. L. Fishbach and B. Herbert. Domestic violence and mental health: Correlates and conundrums within and across cultures. Social Science and Medicine 45,1161–1170, 1997.

117. M.K. Chapo, P. Somse, A.M. Kimball, R.V. Hawkins, and M. Massanga. Predictors of rape in the Central African Republic. Health Care for Women International Jan-Feb;20(1),71–79, 1999.

118. E. Mulugeta, M. Kassaye, and Y. Berhane. Prevalence and outcomes of sexual violence among high school students Ethiopian Medical Journal Jul;36(3),167–174, 1998.

119. D.M. Menick and F. Ngoh. [Sexual abuse in children in Cameroon]. Médecine tropicale: Revue du corps de santé colonial 58(3),249–252, 1998.

120. A.L. Coker and D.L. Richter. Violence against women in Sierra Leone: Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence and forced sexual intercourse. African Journal of Reproductive Health Apr;2(1),61–72, 1998.

121. R. Knight, A. Hotchin, C. Bayly, and S. Grover. Female genital mutilation—Experience of The Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne. Autralian New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Feb;39(1),50–54, 1999.

122. K. Jain, K.A. Maheshwari, and N. Agarwal. Genital injuries in sexually abused young girls. Indian Pediatrics Dec;35(12),1218–1220, 1998.

123. M. D. Stein and L. Hanna. Use of mental health services by HIV-infected women. Journal of Women's Health 6,569–574, 1997.

124. F. K. Judd and A.M. Mijch. Depressive symptoms in patients with HIV infection. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30,104–109, 1996.

125. A. J. Leblanc, S. A. London, and C. S. Aneshensel. The physical costs of AIDS care-giving. Social Science and Medicine 45,915–923, 1997.

126. M. Mbizvo, A. Mashu, T. Chipato, E. Makura, R. Bopoto, Fotrell. Trends in HIV-1 and HIV-2 prevalence and risk factors in pregnant women in Harare, Zimbabwe. Central African Journal of Medicine 42,14–21, 1996.

127. D. Sonali. An Investigation into the Incidence and Causes of Domestic Violence in Sri Lanka. Women in Need (WIN): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1990.

128. S. Toft, ed. Domestic Violence in Papua New Guinea. Law Reform Commission Occasional Paper NO. 19, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1986.

129. S. Valdez and E. Shrader-Cox. Estudio Sobre la Incidencia de Violencia Domestica en una Microregion de Ciudad nezahualcoyotl. Centro de Investigacion y Lucha Contra la Violencia Domestica: Mexico City, 1991.

130. N. Almeida-Filho, J. J. Mari, E. Coutinho, J. F. Franca, J. Fernandes, S. B. Andreoli, and E. A. Busnello. Brazillian multicentric study of psychiatric morbidity. Methodological features and prevalence estimates. British Journal of Psychiatry 171,524–529, 1997.

131. J.C. Campbell and L.A. Lewandowski. Mental and physical health effects of intimate partner violence on women and children. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20,353–374, 1997.

132. N. Malhotra and M. Snood. Sexual assault—A neglected public health problem in the developing world. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics Dec;71(3),257–258, 2000.

133. G.M. Carstairs. Death of a Witch: A Village in North India, 1950–1981. Hutchinson: London, 1983.

134. L. Cohen. No Aging in India. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1998.

135. E. Chinyadza, I. M. Moyo, T. M. Katsumbe, D. Chisvo, M. Mahari, D. E. Cock, O. L. Mbengeranwa. Alcohol problems among patients attending five primary health care clinics in Harare city. Central African Journal of Medicine 36,26–32, 1993.

136. T. F. Babor and M. Grant. Programme on Substance Abuse. Project on identification and management of alcohol-related problems. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1992.

137. C. Pritchard. Suicide in the People's Republic of China categorized by age and gender: Evidence of the influence of culture on suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica May;93(5),362–367, 1996.

138. M.M. Khan and H. Reza. The pattern of suicide of Pakistan. Crisis 21(1),31–35, 2000.

139. A. Alem, D. Kebede, L. Jacobsson, and G. Kullgren. Suicide attempts among adults in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica (supplement); 397,70–76, 1999.

140. C. La Vecchia, F. Lucchini, and F. Levi. Worldwide trends in suicide mortality, 1955–1989. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Jul;90(1),53–64, 1994.

141. World Health Organization (WHO). Stroke trends in the WHO MONICA Project. Stroke 28,500–506, 1997.

142. P. Thorvaldsen, K. Asplund, K. Kuulasmaa et al. Stroke incidence, case fatality, and mortality in the WHO MONICA project. World Health Organization Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease. Stroke 26,361–367, 1995.

143. Bulletin of the Indian Academy of Neurology Nov/Dec 8(3) Bangalore India, 1999.

144. R.S. Murthy. Rural psychiatry in developing countries. Psychiatric Services Jul;49(7):967–969, 1998.

145. V. Patel. Personal communication 2000.

146. Data from the African Medical and Research Foundation, http://www.amref.org/, 2000.

147. Data from the HR Program (Observatory) at Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 2000.

148. Koon Sik Min. Data from the Sam Yook Rehabilitation Center. Personal communication 2000.

149. Hisao Sato, Japan College of Social Work, 2000.

150. B.S. Singhal. Bombay Hospital Institute of Medical Sciences, personal communication 2000.

151. A. Gallo Diop. Centre Hospitalier Universitarie De Fam, Dakar, Senegal. Personal communication, 2000.

152. Annual Congress of the Neurology Association of South Africa, 1998.

153. CIA World Fact Book, 2000.

154. Pan American Health Organization Scientific Publication, 561.

155. Data from the Uruguay Medical Society, 2001.

156. Meeting on Promotion of Psychiatry and Mental Health in Africa, 2000.

157. World Bank. Entering the 21st Century World Development Report 1999/2000. Oxford University Press: New York, 2000.

158. A. Alem. Human rights and psychiatric care in Africa with particular reference to the Ethiopian situation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica (supplement) 399,93–96, 2000.

159. A. Mohit, K. Saeed, D. Shahmohammadi, J. Bolhari, M. Bina, R. Gater, et al. Mental health manpower development in Afghanistan: A report on a training course for primary health care physicians. Eastern Mediterrean Health Journal Mar;5(2),373–377, 1999.

160. V. Ganju. The mental health system in India. History, current system, and prospects International Journal of Law and Psychiatry May-Aug;23(3–4):393–402, 2000.

161. Data from the Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University. Cairo, Egypt, 2000.

162. WHO Estimates of Health Personnel in http://who.int.org.

|

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS: Integrating Care of Brain Disorders into Health Care Systems

|