8

Bipolar Disorder

DEFINITION

One of the first descriptions of mania dates from 30AD,[1] but it was not until the conceptual separation of schizophrenia from other psychoses and the description of mania by Kraepelin in 1921 [2] that focused research and attempts to define mania accurately began. The discovery of lithium therapy as an effective treatment for mania argued for the origins of this disorder as being biological. The subsequent research precipitated by these findings revealed bipolar disorder (also known as manic-depressive illness) as a distinct diagnosable condition.

Despite the strong neurobiological indicators that have been discovered for bipolar disorder,[3,4,5 and 6] diagnosis is made on the basis of characteristic symptoms of mood disorder, which include alternating episodes of extreme elevation of mood (mania) and severe depression.[7] Elevated mood can be accompanied by delusions, hallucinations, insomnia, and extreme excitement, and depressive states by persistent low mood or sadness that is accompanied by both physical and psychological symptoms of at least 2 weeks duration and an associated impact on social functioning.

Kraepelin characterized manic psychosis by its periodic course, good prognosis, and mood symptoms in the acute phase.[2] It is important to note that bipolar disorder remains a clinical syndrome and that the neurobiology underlying its causes is not yet fully known. There is at present no biological test or marker that can identify the disease (or a predisposition to it) independently of clinical assessment (e.g., recognizing a family history of the disorder). Both standardized diagnostic mechanisms for disease, the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) ,[8] and the (APA) Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual, fourth edition (DSM-IV) still rely on the course of the illness (see table 8-1 and table 8-2) [9]:

-

Bipolar I = at least one manic (elevated mood) episode (hypomania = less severe presentation without the need for hospitalization or impediment to occupational or social functioning).

-

Bipolar II = at least one episode of mania or hypomania and a full major depressive episode.

In contrast with other psychoses, the psychotic symptoms of bipolar disorder must be congruent with the prevailing elated or depressed mood state. For these purposes, irritability is presumed to be congruent with an elated or elevated mood state.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Mortality

The evidence clearly reveals the exceedingly high mortality rate from suicide exacted by bipolar disorder. Evidence from developed countries has shown varying rates for attempted suicide of between 25 and 50 percent among patients with the disorder.[10,11] Follow-up studies have found that as many as 15 percent were completed suicides. This rate is approximately 30 times greater than the rate for general populations.[11,12]

In developing countries, similar rates of suicide have been observed.[ 13,14] High rates of attempted suicide (24 percent) were found in a study conducted in a psychiatric hospital in Taiwan.[15] An earlier age of onset, interpersonal problems with partners and close family members, and occupational maladjustment rather than demographic characteristics are suggested as collectively identifying those with bipolar disorder at high risk of suicide attempt.

Social and Economic Costs

In light of the findings of the 1996 Global Burden of Disease study and more recent estimates of the same measurements of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), neuropsychiatric conditions have been recognized as a significant social and economic burden (see Chapter 2).[16,17] Bipolar disorder is considered to represent 11 percent of the disease burden from neuropsychiatric conditions in low- and-middle income countries. Moreover, within these estimates for low- and middle-income countries, bipolar disorder is estimated to account for a full 1.1 percent of all categories of disease burden. When estimating the disability weight measurements for the Global Burden of Disease study, the burden of bipolar disorder was weighted somewhere between that of paraplegic and quadriplegic physical disability.[16]

TABLE 8-1 Overview of the DSM-IV Criteria for Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

|

Bipolar Disorder I |

Bipolar Disorder II |

|

|

|

Specify if: Mixed: if symptoms meet criteria for a mixed episode. |

|

|

Specify (current or most recent episode):

|

Specify (current or most recent episode):

|

|

Specify (for current or most recent major depressive episode only if it is the most recent type of mood episode):

|

|

|

Specify:

|

|

|

Source: [9] |

|

TABLE 8-2 Overview of the ICD-10 Criteria for Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

|

F.30 Manic Episode Three degrees of severity are specified here, sharing the common underlying characteristics of elevated mood, and an increase in the quantity and speed of physical and mental activity. All the subdivisions of this category should be used only for a single manic episode. If previous or subsequent affective episodes (depressive, manic, or hypomanic), the disorder should be coded under bipolar affective disorder. F.32 Depressive Episode In typical depressive episodes of all three varieties described below (mild, moderate, and severe), the individual usually suffers from depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, and reduced energy leading to increased fatiguability and diminished activity. Marked tiredness after only slight effort is common. Other common symptoms are:

The lowered mood varies little from day to day, and is often unresponsive to circumstances, yet may show a characteristic diurnal variation as the day goes on. As with manic episodes, the clinical presentation shows marked individual variations, and atypical presentations are particularly common in adolescence. In some cases, anxiety, distress, and motor agitation may be more prominent at times than the depression, and the mood change may also be masked by added features such as irritability, excessive consumption of alcohol, histrionic behaviour, and exacerbation of pre-existing phobic or obsessional symptoms, or by hypochondriacal preoccupations. For depressive episodes of all three grades of severity, a duration of at least 2 weeks is usually required for diagnosis, but shorter periods may be reasonable if symptoms are unusually severe and of rapid onset. |

|

Source: [8] |

Bipolar disorder is a chronic disease with high frequencies of relapsing symptoms that often worsen over time, even when appropriate pharmacotherapy is administered.[18] During both manic and depressive states, sufferers are often limited in their social, familial, and employment roles.[19,20] Several recent studies in developed countries found that patients with bipolar disorder had substantial impairment in health-related quality of life in comparison with the general population.[21,22] Bipolar patients were less compromised in areas of physical functioning than chronic back pain patients, but had similar impairment in overall mental health and social functioning.[23]

Despite the identification of bipolar disorder early in the 20th century and prevalence rates in developed countries that are higher than those for nonaffective psychoses, less research has been conducted in these countries on this disorder in comparison to other psychiatric conditions (including those discussed elsewhere in this report). In developing countries, an even smaller and similarly inconclusive body of research exists. For the purposes of this report, we include, where applicable, data from one or both settings and where possible make comparisons

between them. After reviewing the literature, the committee concluded that more investigation into the etiology of and interventions for bipolar disorder are needed to reduce its long-term debilitating effects. Recent advances in genetic research have greatly increased the potential for unraveling the complex neurobiology of bipolar disorder and meeting the challenges involved in its treatment.

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

According to the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey,[24] bipolar affective disorder is nearly three times more prevalent than nonaffective psychoses. However, bipolar disorder has not been investigated on the same scale, for example, in a large-scale international comparative study on schizophrenia (such as the study described in Chapter 7), to validate the cross-cultural reliability of diagnosis between developed- and developing-country settings. Nevertheless, in a cross-cultural study that included two developing countries and used a single, standardized diagnostic method, lifetime rates of bipolar disorder were found to be similar across populations (0.3/100 in Taiwan and 1.5/100 in New Zealand).[25] Another study in India using standard DSM-III-R criteria found rates of diagnosis and course of illness in children and adolescents to be similar to the findings in developed countries.[26]

However, when comparisons are made both within and between countries the evidence points to some variation in both the incidence and prevalence of the symptoms of bipolar affective disorder.[27,28,29,30,31,32 and 33] In the United States, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study used DSM-III criteria.[27] It reported a lifetime prevalence of 2.7 percent for a manic episode. Manic symptoms were more common in the 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 and 29 age group and more common in men than women. Yet there was no significant sex difference in actual bipolar disorder. The lifetime prevalence of Bipolar I was 0.8 (0.7 male, 0.9 female), and that of Bipolar II was 0.5 (0.4 male, 0.5 female). There was also no ethnic difference in the rate of these disorders. However, there was a difference in the rates of illness among study sites.

Population-based studies in Italy showed a higher 1-year prevalence in women (1.86 percent) than in men (0.65 percent), with an overall Bipolar II rate of 0.2 percent.[28] In Taiwan, the prevalence for a manic episode was found to be between 0.7 and 1.6 percent, depending on whether a city or small town was studied.[29] In Puerto Rico, the prevalence of a manic episode was 0.7 for males and 0.4 for females,[30] and similar rates were found in Alberta, Canada.[31] A study in the Netherlands found much lower rates of 0.1 percent for a manic episode in both genders.[32]

Prevalence is dependent not only on the rate of new illness, but also on the availability of medical interventions and social buffers to the development of symptoms. Incidence studies are a better index of illness rates, but there are few such studies. Incidence studies in Scandinavia have reported rates of 9.2–15.2

cases per 100,000 for men and 7.4–32.5 cases per 100,000 for females.[33] A retrospective study of hospital admission rates in Denmark and the United Kingdom has been used as a proxy measure for incidence —virtually identical rates of 2.6 per 100,000 were found in both centers.[ 34]

A recent WHO study found comparable rates of mood disorders in Mexico and Brazil as compared with the United States, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands.[35] However, the results included no indication of the proportion of mood disorders that were unipolar and bipolar. Research has shown significant variations among countries in the ratio of unipolar to bipolar illness, but even the most conservative estimate would identify bipolar illness as a significant health problem in the developing countries.

Few studies of bipolar disorder have been conducted in developing countries and many of these have offered inconclusive and variable evidence, as illustrated by the examples described below.

In India, Brown et al. looked at affective psychosis in Chandigarh and found that all 24 patients with mania experienced full recovery within a 1-year period. At 1-year follow-up, 75 percent of manic patients demonstrated no symptoms or social impairment. The mean episode duration was 10.2 weeks, and the rate of relapse was 21 percent. Overall, these outcomes are considerably more favorable than those found in comparable studies of affective disorders in developed-country settings.[36]

Higher rates of bipolar disorder were found among some Indonesian groups and the Hutterites in North America [37] as compared with their overall population rates. Among Jewish people of European background in the United States, the rates are higher than among those of North African background.[38] Bazzoui found that 44 percent of patients admitted with affective disorder in Iraq suffered from bipolar disorder.[39] Though only a fifth of people suffering from affective disorders in Sweden suffer from bipolar disorder, one in three such patients in Jerusalem suffers from the disorder.[40]

Khanna et al. investigated the course of bipolar disorder in India. In their consecutive admission sample, they found that recurrent mania was common, and there was a significantly greater frequency of manic compared with depressive relapses.[41] They also found a marked preponderance of male subjects. This finding may have been due in part to their methodology, but this is unlikely to be a complete explanation. It may be that the low female admission rates reflect sociocultural determinants of admission. The greater tendency for men to display aggressive behavior may mean that their symptoms are less well tolerated socially than in females. Moreover, the greater economic impact of men's incapacity to work may influence their admission rate, and the stigma of mental illness in a culture in which marriages are arranged may decrease the rate of female admission.

RISK FACTORS

Genetic

Evidence for high aggregates of familial risk and results of recent research conducted in developed countries to elicit genetic linkage in families with bipolar disorder supports the argument for a significant genetic contribution to the etiology of bipolar disorder.[42,43,44,45,46,47 and 48] However, the findings reported to date are inconsistent and larger-scale replication of many of these studies will be required before the evidence is conclusive.[3] Data from a recent French study suggest that early- and late-onset bipolar disorders differ in clinical expression and familial risk, and may therefore foreshadow findings of different subforms of the disorders within genetic research.[49]

It is known that there is a 1.5 percent lifetime risk for the children of an affected person, 6 percent for brothers, 4.1 percent for mothers, and 6.4 percent for fathers.[24] In a recent U.S. study, the offspring of parents with early-onset bipolar disorder were found to experience high levels of psychopathology.[ 50] Studies in both developed and developing countries showing high familial risk for bipolar disorder indicate that establishing the diagnosis of a family member with the disorder can be an important factor in attempting to diagnose children who may present with symptoms common to other disorders, such as attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder as well as adults who may present only with symptoms of unipolar depression.[26,51,52 and 53] Correct diagnosis is, of course, essential to ensure the appropriate course of treatment, which differs significantly among these disorders.

Substance Abuse

Data from both developed and developing countries countries reveal high levels of comorbidity in bipolar illness. Data collected on bipolar disorder show rates of substance abuse that are 5–6 times greater than those among general populations.[13,54] Three studies found the rate of substance misuse in those with Bipolar I disorder to be over 60 percent, and at least 35 percent of total bipolar disorder cases were complicated by alcohol abuse.[ 24,55] A diagnosis of an underlying bipolar illness may be missed because of the high rate of comorbidity and the more conspicuous signs and symptoms of substance abuse.[56]

Strakowski and DelBello's recent review of the existing literature on the co-occurrence of bipolar disorder and substance abuse found evidence to support four distinct hypotheses to explain this association: 1) substance abuse occurs as a symptom of bipolar disorder; 2) substance abuse is an attempt by bipolar patients to self-medicate symptoms; 3) substance abuse causes bipolar disorder; and 4) substance use and bipolar disorders share a common risk factor. The variability in findings from the existing evidence suggests that additional studies to examine the relationship between substance abuse and bipolar disorder are

needed. Future studies that increase the understanding of this frequent co-occurrence may eventually provide guidance toward improved prevention and treatment strategies for both conditions.[57]

Environmental

Several studies have indicated that social conditions and experiences contribute to both the onset and recurrence of relapse in bipolar disorder. Striking urban–rural differences have been found, with the illness being three times more common in urban than in rural populations.[58] It is still unclear whether variations in the rates of mania among different populations are due to genetic loading or societal factors.

Associations with Age and Gender

Findings of recent studies in developed as well as developing countries estimate the peak age of onset for bipolar disorder between 18 and 24.[26,58,59] Though the age of onset and number of affective episodes of each polarity have not been shown to differ between men and women,[24] some studies have shown that women experience depressive episodes of the disorder more frequently and men have been shown to be at greater risk for manic episodes.[60,61,62 and 63]

Several studies have yielded similar findings for childhood-onset bipolar disorder. Irritability was the predominant affective disturbance in younger manic children, but prepubertal bipolar children began their illness with cycles of dysphoria, hypomania, and agitation intermixed, and increasingly extreme cycles of manic and depressive states became more common with the onset of puberty.[64,65] Adolescents who are early into their illness are often prone to highly elevated mood states and grandiose delusions resulting in poor adherence to treatment.[11,53] Similar findings on the course of bipolar disorder in children have been reported in India.[25,51]

Factors Affecting Course and Outcome

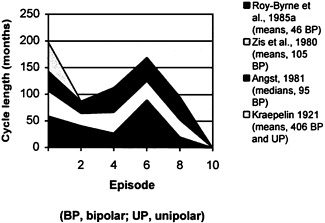

Bipolar disorder is quite disabling because of its recurrent course, frequency of suicidal ideation, and significant impact on social functioning during acute episodes of both polarities.[66] Data on the frequency of variable levels of recurrence are inconsistent, yet telling. An older study found that patients averaged as many as 12 episodes during a 25-year period.[67] Winokur et al. (1994) estimated that over a 10-year period, patients averaged three episodes and five hospitalizations.[68] Even with pharmacological intervention, those suffering one manic episode almost always go on to have another.[69,70] Ongoing and significant symptoms between major episodes occur even in individuals who suffer infrequent acute episodes.[71]

Figure 8-1 Increasing probability of relapse with each episode of manic-depressive illness. Source: [11]

Despite the likely significant mortality, morbidity, and burden on families developing countries is very limited. If the epidemiology in the developed world is applicable, the burden in developing countries would be significant. The impact of social and environmental factors on the presentation, course, and incidence of the illness argues for the need for much more work to delineate the treatment needs in developing countries. This work could also lead to vital etiological data that could inform primary prevention interventions in both developed and developing countries.

Recommendation 8-1. Research to determine the applicability of current diagnostic methods in the local settings of developing countries should be conducted to better understand the epidemiology of bipolar disorder in developing countries and to ensure the effectiveness of efforts to identify and treat the disease within various health care settings. Research to determine the local risk factors and patterns of heredity for bipolar disorder should also be undertaken to further inform effective courses of intervention.

Recommendation 8-2. Large-scale population-based studies in developing countries should be carried out to expand and validate the findings of previous studies relative to bipolar disorder, particularly in the area of genetic research. The existence of isolated populations and extended family environments in parts of the developing world may provide uniquely appropriate settings for such research. Collaborative efforts between researchers in developing countries and well-equipped research institutions in developed countries should be emphasized, in part to build the research capacity of developing-country centers.

INTERVENTIONS

Prevention

Currently, there is no known method or strategy of primary prevention for bipolar disorder. Even for those at risk because of familial history, no method to eliminate or preempt the origins of the disease exists. Once the disorder has been diagnosed, risk factors and the physical and psychological symptoms can be reduced and controlled, but not eliminated. Nevertheless, research into presymptomatic detection of bipolar disorder is important,[72] and the prospect of prevention is likely to become increasingly realistic with advances in knowledge of the genetic basis for the disorder and its neurodevelopmental pathophysiology.

Treatment

Though no current data are available, the conspicuous lack of research on bipolar disorder in developing countries would support the argument that effective treatments currently available in developed countries are not reaching those suffering from the disorder elsewhere. Even in developed countries, the treatment of bipolar disorder is underinvestigated. The complexity of the disorder and the variability of its symptoms make clinical treatment a complicated endeavor.[72] Treatment often requires a combination of medications, and caution must be exercised because of the high rate of significant side effects. Because of the lack of available data from developing countries, the following discussion on treatments for bipolar disorder is based on the research literature of developed countries. Where very limited information from developing countries is available, it is noted.

The difficulty of clinical diagnosis for bipolar disorder is twofold. First, those who are experiencing the manic phase of the disorder do not usually seek treatment because this period is characterized by highly elevated mood states. Often it is only when patients present with high levels of agitation or aggression that treatment will be pursued. Second, those who seek treatment when experiencing the depressed state of the disorder are frequently diagnosed with unipolar

depression. Though bipolar and unipolar disorders are clinically recognized as distinct, the lack of research on distinguishing the pathophysiology of the conditions provides little support for more accurate diagnosis.[41,61] Moreover, the stigma associated with mental illness in developing countries (see Chapter 2) is often a major deterrent in individuals seeking treatment for psychological problems or feelings of emotional distress.

For the majority of patients in developed countries, treatment and care need to be provided on a lifelong basis, with periodic reviews of outcome and adjustment of the mix of interventions according to need and the phase of the illness. It is of overriding importance to recognize that the symptoms and behavioral impairments associated with bipolar disorder are shaped by interactions between intrinsic vulnerabilities caused by the disease and the psychosocial environment. Good practice in the management and treatment of bipolar disorder requires addressing both sides of this interaction.

TABLE 8-3 Critical Challenges in the Stages of Pharmacological and Psychosocial Treatment

|

Stage |

Goals of Treatment |

Issues for Patient/Family |

|

Acute |

Gain control over severe symptoms |

Trauma and shock, dealing with police and/or hospitalization (in some cases), making sense of what has happened |

|

Stabilization |

Hasten recovery from the acute episode, address residual symptoms/impairment, encourage medication compliance |

Adapting to post-episode symptoms and social–occupational deficits, financial stress, accepting a regular medication regime, uncomfortable discussions about medication and illness, denial about the realities of the disorder |

|

Maintenance |

Prevent recurrences, alleviate residual affective symptoms, continue to encourage medication compliance |

Fears about the future, accepting the illness and the vulnerability to future episodes, coping with ongoing deficits in social–occupational functioning, issues surrounding long-term medication adherence |

|

SOURCE: [66] |

||

Pharmacotherapy

Recurrent affective disorders often require treatment to prevent relapse, as well as to alleviate acute episodes. Acute episodes of mania are best treated with antipsychotic (typical and atypical) medication (see Chapter 7 on considerations for the use of antipsychotics in developing countries), though they can be treated with high doses of mood stabilizers. Because the significant side effects from typical antipsychotics, particularly tardive dyskinesia, tend to occur with greater frequency in bipolar patients as compared with those suffering from schizophrenia and other psychoses,[73,74 and 75] their use should be minimized, and preference may be given to high doses of mood stabilizers.[76] Acute episodes of depression can be treated with antidepressant medication and electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) (see Chapter 9 on considerations for the use of antidepressants and ECT in developing countries). However, particular caution must be exercised in the use of tricyclic antidepressants because the data suggest that they can trigger episodes of mania, hypomania, and rapid cycling in bipolar patients.[77] Once acute symptoms are under control, decisions about prophylaxis need to be made. It is important to treat bipolar disorder actively because each episode of mania increases the risk of progression of the illness, with increasingly severe episodes occurring with greater frequency.[78]

Mood Stabilizers

The following commonly used mood stabilizers have some antidepressant effect, but are prescribed mainly for the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder.

Lithium is the best-investigated mood stabilizer. It is used for the treatment of mania and for the prophylaxis of bipolar and unipolar affective disorders.[79,80 and 81] Retrospective studies ranging from 4 months to 3 years indicate that the relapse rate for bipolar patients treated with placebo is 80 percent, while the relapse rate for those treated with lithium is as low as 35 percent.[78,82] Lithium has been shown to decrease the severity as well as the frequency of episodes.[11,83,84] Those with a family history of bipolar affective disorder and complete recovery between relapses are likely to respond to lithium. Patients whose first episode is manic rather than depressive and those who have a good response to lithium during the acute episode tend to respond to prophylaxis. Lithium has been noted as the most influential medication for preventing suicidal behavior.[85] Patients with neurological signs or mania secondary to cerebral injury respond less well, as do patients who are rapid cycling and those with histories of drug abuse.[79,80]

The side effects of lithium reflect its effects on numerous bodily systems. Most patients experience at least one side effect.[84] Thyroid function may be reduced; patients with existing thyroid illness or family histories of the illness are at increased risk for this side effect.[84] In one-third of patients, changes in the

architecture of the kidneys are apparent within the glomerulus and tubules. However, these changes rarely lead to deterioration in renal function, except when toxicity has occurred.[84] A fine tremor is reported by 25 percent of patients. A few patients develop Parkinsonian features, which are not amenable to treatment with anticholinergic drugs.[80] A number of other side effects have been described,[86] including reversible t-wave flattening and abdominal discomfort. In the first trimester of pregnancy, 4–12 percent of exposed babies will develop congenital malformations.[87] Lithium toxicity can be life-threatening, and patients who have survived it may be left with permanent cerebellar signs.[88]

Lithium is currently considered the first-line, most appropriate medication for acute bipolar depression and the first-line monotherapy for the treatment and prophylaxis of bipolar disorder.[89,90] Data from a recent study in Iran show a lower ratio of lithium to side effects in patients treated only with lithium than in those treated with combinations of lithium and neuroleptics.[91]

Carbamazepine has been tested for efficacy in only a few small placebocontrolled trials.[92] The mood-stabilizing action of carbamazepine was first reported in 1973.[93] Carbamazepine has shown possible antimanic and antidepressant effects as a monotherapy or in combination with lithium.[94,95] Patients with dysphoric mania, mixed states, no family history of bipolar disorder, mania following brain injury, or a history of rapid cycling may be more likely to respond initially to carbamazepine than to lithium. However, there is some evidence that the effects of carbamazepine decrease 3 years or so into treatment.[96] A combination of lithium and carbamazepine is more effective than either monotherapy in the treatment of rapid cycling.[97]

The most common side effects are nausea, dizziness, diplopia, and ataxia. Among 15 percent of patients, an itchy rash develops within 2 weeks of starting treatment. A number of idiosyncratic side effects have been described as well, such as a small percentage of patients who develop agranulocytosis.[98,99 and 100]

Sodium valproate has been shown to be effective for mania and for mixed affective states. It is useful in patients who are resistant to lithium and carbamazepine, and may be especially valuable in preventing relapse of depression, rapid cycling, or mixed states in bipolar patients,[ 101] as well as in treating elderly patients.[78] There are a number of dose-dependent side effects, including nausea and stomach cramps, hair thinning, lethargy, and elevated liver function, which can be managed by decreasing the dose. Agranulocytosis, liver failure, and pancreatitis are idiosyncratic reactions that contraindicate further treatment. A fetal valproate syndrome has been described that includes congenital malformations, jitteriness, and seizures in the fetus.[102]

Other Mood Stabilizers

A number of other drugs have been used as mood stabilizers, either by themselves or as adjunctive therapy. Clonazepam is used as adjunctive therapy

with lithium, and verapamil and lamotrigine are used acutely and also as prophylaxis in cases of treatment failure with lithium or carbamazepine. There are also a number of new drugs currently undergoing trials, but to date none of these equals current treatments in risk-benefit analysis and their effects on unipolar disorder have not been adequately reported. Most of these mood stabilizers are relatively expensive as compared with lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate. Additionally, despite concerns about the described side effects of lithium, a recent review of existing research regarding the use of lithium for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder concluded that it should remain the first-line treatment.[103]

In developed countries, the drugs discussed previously have been shown to be effective and because they are available in generic form they are relatively low cost. Only limited analysis has been done to determine actual cost-effectiveness, but given the highly disabling effects of this disorder it is likely that cost-effectiveness will bear out in future studies.[22,104] No evidence exists for developing countries, but the need for blood monitoring poses unique challenges even when low-cost medications may be available. Problems encountered with the development of therapeutic drug monitoring in India have been highlighted by Gogtay et al.[ 105] They found that the service was available only in large teaching hospitals or in the private sector. Lack of funding and problems with the quality of medicines and the availability of generic products made quality control difficult and increased the risks associated with drug toxicity.

The limitations imposed by the cost of long-term prophylaxis drug treatment in India affect the current practice regarding the use of prophylaxis treatment beyond five years. Upon review of the first five years of treatment, the occurrence of relapse is examined and if no relapse has occurred then drug treatment is stopped. Decisions regarding the continuation of drug treatment for patients still experiencing relapse are based on the frequency of relapse and periodic review of the course of illness thereafter.[106]

Better epidemiological and treatment outcome data is needed in developing countries to determine the need for and course of treatment for bipolar disorder in local health care settings.

Psychosocial Treatment

Bipolar disorder is characterized by high rates of relapse of the acute states of polarity even when patients are maintained on proper pharmacotherapy. It has been argued that stressful life events and disturbances in social-familial support systems affect the cycling of the disorder in the context of other genetic, biological, and cognitive vulnerabilities.[107,108] Some current models of psychosocial treatment focus on modifying the effects of social or familial risk factors and may help improve the course of the disorder.[109,110,111 and 112]

Adjunctive psychotherapy may assist patients in understanding the implications of having bipolar disorder and assist with more positive attitudes about compliance with drug therapy to avoid more frequent relapses involving manic or depressive episodes. Individual, family, or group psychotherapy may help both patients and families address feelings of denial, difficulties with interpersonal functioning, and concerns about worsening of the disorder.[11,113] Therapeutic and nonjudgmental environments allow for open discussion of symptoms, treatments, and their side effects. Such discussion can create long-term stability, optimize compliance, and allow for early identification and intervention when relapsing episodes occur.[ 114]

Preliminary research has been conducted on three models of psychotherapy that are beneficial for bipolar disorder and may be applicable in developing countries: problem-solving therapy, interpersonal therapy, and family-focused treatments for psychoeducation and communication enhancement.[66,115,116 and 117] Where resources are limited, it may be difficult to implement psychotherapy treatments that require specialized knowledge of mental illness and lengthy periods of training.

Recommendation 8-3. Lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate, considered by WHO to be “essential medications” for bipolar disorder, should be made readily available to developing-country medical facilities for the treatment of the disorder. Additionally, treatment programs that make mobile facilities for blood monitoring more readily available to more remote populations should be developed to enable appropriate courses of treatment that avoid the toxic and sometimes lethal side effects of mood stabilizers.

Recommendation 8-4. Side effects of treatment can be intolerable for some patients, and lack of adherence to drug treatment is a frequent obstacle to effective treatment of bipolar disorder with mood stabilizers. Stressful life events and other social factors are suspected to contribute to the onset and frequency of relapse as well. Programs that promote adherence to drug treatment in conjunction with psychosocial therapy should therefore be implemented within community-based management programs for health care. Training for family-based therapy should be provided to those in the households of bipolar patients.

Recommendation 8-5. Current knowledge of bipolar disorder suggests that biological vulnerability affecting brain development and function and environmental influences, including psychosocial factors, interact and potentiate each other at every stage of the disorder—preclinical, acute, and residual. Programs aiming at early treatment, stabilization, and rehabilitation of those afflicted must

consider this essential feature of bipolar disorder and engage the system as a whole—the patient, the family, and the community. Programs to limit the chronicity of bipolar disorder should also address substance abuse and suicidal behavior frequently associated with patients suffering from this disorder.

Recommendation 8-6. Randomized controlled trials (in the form of large-scale demonstration projects) of pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial treatments should be conducted to identify locally cost-effective methods of treatment.

CAPACITY

The generic primary health care model (see Chapter 3) is probably the single most important vehicle for providing essential care within the community to the majority of patients with bipolar disorder in the developing world. The model is well adapted to the acute shortage of medical staff in rural areas and redefines the role of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals as being focused primarily on providing training; designing methodological tools, such as problem detection and treatment guidelines; and offering tertiary consultation.[27,28,29 and 30]

The primary health care model has been implemented in a number of developing countries. The lack of systematic data collection and exchange of information across the developing world, however, makes it impossible to determine if bipolar disorder is being properly diagnosed or treated within these settings. The findings of large-scale epidemiological studies would inform the process of priority setting and health planning for developing countries. Currently, the high prevalence and significantly disabling effects of bipolar disorder, found in developed countries and a limited number of developing countries along with the disproportionately high rates of suicide associated with the disease, argue for placing effective interventions on the public health agenda of national and local planners.

Recommendation 8-7. Randomized controlled trials of the efficacy and feasibility of affordable community-based management programs for those with bipolar disorder (within the context of the extended health care system) should be conducted to determine the most appropriate programs for treatment. Using the evidence from developed countries as a guide, initial trial programs should have three specific aims:

-

Reduce the frequency of manic and depressive relapses;

-

Reduce the risk of premature mortality due to suicide; and

-

Reduce stigma, and protect the patient's human rights.

Such a program should involve at least three operational components:

-

Adaptation of existing screening and diagnostic tools for bipolar disorder, with a view to accounting for differences in the local presentation of the disorder and making them suitable for use by personnel in the primary care setting.

-

Pharmacological treatment, with specific guidelines for symptom control in acute episodes, maintenance of stabilization and prevention of relapse, and means of ensuring adherence to the treatment protocol.

-

Mobilization of family and community support, including providing education on the nature of the disorder and its treatment, involving the family in simple problem-solving training, and involving the local community in providing a supportive and nonstigmatizing environment.

REFERENCES

1. F. Adams. The extant works of Aretaeus, the Cappadocian. London, The Syndenham Society 1856. Reprinted in the Classics of Medicine Library Series. Gryphon Editions Inc.: Birmingham, AL, 1990.

2. E. Kraepelin. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. E&S Livingstone: Edinburgh, 1921.

3. C. Friddle, R. Koskela, K. Ranade, J. Hebert, M. Cargill, C.D. Clark, M. McInnis, S. Simpson, F. McMahon, O.C. Stine, D. Meyers, J. Xu, D. MacKinnon, T. Swift-Scanlan, K. Jamison, S. Folstein, M. Daly, L. Kruglyak, T. Marr, J.R. DePaulo, and D. Botstein. Full-genome scan for linkage in 50 families segregating the bipolar affective disease phenotype. American Journal of Human Genetics 66:205–215, 2000.

4. D.H.R. Blackwood, L. He, S.W. Morris, A. McLean, C. Whitton, M. Thomson, et al. A locus for bipolar affective disorder on chromosome 4p. Nature Genetics 12:427–430, 1996.

5. E.I. Ginns. A genome-wide search for chromosomal loci linked to bipolar affective disorder in the Old Order Amish. Nature Genetics 12:431–435, 1996.

6. N.B. Freimer, et al. Genetic mapping using haplotype, association and linkage methods suggests a locus for severe bipolar disorder (BPI) at 18q22–q23. Nature Genetics 12:436–441, 1996.

7. A.L. Stoll, M. Tohen, Baldessarini, D.C. Goodwin, S. Stein, S. Katz, et al. Shifts in the diagnostic frequencies of schizophrenia and affective disorders from 1972 through 1998; A combined analysis from four North American psychiatric hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:130–132, 1994.

8. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1992.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. American Psychiatric Association: Washington D.C., 1994.

10. M.A. Oquendo, C. Waternaux, B. Brodsky, B. Parsons, G.L. Haas, K.M. Malone, and J.J. Mann. Suicidal behavior in bipolar mood disorder: Clinical characteristics of attempters and nonattempters. Journal of Affective Disorders 59(2):107–117, 2000.

11. F.K. Goodwin and K.R. Jamison. Manic-Depressive Illness. Oxford University Press: New York, 1990.

12. G.K. Brown, A.T. Beck, R.A. Steer, and J.R. Grisham. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68(3):371–377, 2000.

13. S.Y. Tsai, J.C. Lee, and C.C. Chen. Characteristics and psychosocial problems of patients with bipolar disorder at high risk for suicide attempt. Journal of Affective Disorders 52(1–3):145–152, 1999.

14. A. Ucok, D. Karaveli, T. Kundakei, and O. Yazici. Comorbidity of personality disorders with bipolar mood disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry 39(2):72–74, 1998.

15. C.Y. Liu, Y.M. Bai, Y.Y Yang, C.C. Lin, C.C. Sim, and C.H. Lee. Suicide and parasuicide in psychiatric inpatients: Ten years experience at a general hospital in Taiwan. Psychological Reports 79(2):683–690, 1996.

16. C. Murray and A. Lopez, eds. The Global Burden of Disease. Boston: The Harvard Press, 1996.

17. WHO (World Health Organization). The World Heath Report. Geneva: 1999.

18. T.C. Monschreck and A.H. Leighton. Reducing disability in mood disorders and schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:262–265, 1992.

19. J.M. Murphy, D.C. Oliver, A.M. Sobol, R. R. Monson, and A.H. Leighton. Diagnosis and outcome: Depression and anxiety in a general population Psychological Medicine 16:117–126, 1986.

20. P. Martin. Impacts économiques des troubles bipolaires de l'humeur. Encephale 23(Spec No 1):49–54, 1997.

21. G.M. MacQueen, L.T. Young, J.C. Robb, M. Marriott, R.G. Cooke, and R.T. Joffe. Effect of number of episodes on wellbeing and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101(5):374–381, 2000.

22. K.B. Wells and C.D. Sherbourne. Functioning and utility for current health of patients with depression or chronic medical conditions in managed, primary care practices Archives of General Psychiatry 56(10):897–904, 1999.

23. L.M. Arnold, K.A. Witzeman, M.L. Swank, S.L. McElroy, and P.E. Keck Jr. Health-related quality of life using the SF-36 in patients with bipolar disorder compared with patients with chronic back pain and the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 57(1-3):235–239, 2000.

24. R.C. Kessler, K.A. McGonagle, S. Zhao, C.B. Nelson, M.Hughes, S. Eshleman, et al. Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-III-R, psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994.

25. M.M. Weissman, R.C. Bland, G.J. Canino, C. Faravelli, S. Greenwald, H.G. Hwu, et al. Cross-National Epidemiology of Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder Journal of the American Medical Association Jul 24/31; 276(4), 1996.

26. Y.C. Reddy, S. Girimaji, and S. Srinath. Clinical profile of mania in children and adolescents form the Indian subcontinent. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42(8):841–846, 1997.

27. L. N. Robins, J. E. Helzer, M. M. Weissman, H. Orvaschel, E. Gruenberg, J. D. Burke, et al. Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites . Archives of General Psychiatry. 41:949–958, 1984.

28. C. Faravelli, B.C. Deg'llnnocenti, L. Azzi, G. Incerpi, and S. Pallanti. Epidemiology of mood disorders: A community survey in Florence. Journal of Affective Disorders 20:135–141, 1990.

29. H. G. Hwu, E. K Yeh, and L.Y. Chang. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:136–147, 1989.

30. G.J. Canino, H.R. Bird, P.E. Shrout, M. Rubio-Stipee, M. Bravo, M. Sesman, et al. Prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:727–735, 1987.

31. R.C. Bland, S.C. Newman, H. Orm, eds. Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 77 (Suppl 338), 1988.

32. P. Hodiamont, N. Peer, and N. Syben. Epidemiology aspects of psychiatric disorder in a Dutch health area . Psychological Medicine 17:495–505, 1987.

33. J.H. Boyd and M.M. Weissman. Epidemiology of affective disorders: A reexamination and future directions . Archives General Psychiatry 38:1039–1046, 1981.

34. J.O. Leff, M. Fisher, and A. Bertelsen. A cross national epidemiological study of mania. British Journal of Psychiatry 129:428–442, 1976.

35. WHO (World Health Organization). International consortium in psychiatric epidemiology. Cross national comparisions of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(4):413–426, 2000.

36. A.S. Brown, V.K.Varma, S.Malhotra, R.C. Jiloha, S.A. Conover, and E.S. Susser. Course of acute affective disorders in a developing country setting . Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 186(4);207–213, 1998.

37. J.W. Eaton and R.J. Weil. Culture and mental disorders: A comparative study of the Hutterites and other populations. New York: New York Free Press, 1955.

38. E. S. Gershon and J.H. Liebowitz. Socio-cultural and demographic correlates of affective disorders in Jerusalem. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:37–50, 1975.

39. W. Bazzoui. Affective disorders in Iraq. British Journal of Psychiatry 117:195–203, 1970.

40. R.H. Belmaker and H.M. Van Praag. Mania and evolving concept. New York: Spectrum, 1980.

41. R. Khanna, N. Gupta, and S. Shanker. Course of bipolar disorder in eastern India. Journal of Affective Disorders 24:35–41, 1992.

42. D.F. MacKinnon, K.R. Jamison, and J.R. DePaulo. Genetics of manic depressive illness. Annual Review of Neuroscience 20:355–373, 1997.

43. W.H. Berrettini, T.N. Ferraro, L.R. Goldin, D.E. Weeks, S. Detera-Wadleigh, J.I. Nurnberger Jr, et al. Chromosome 18 DNA markers and manic-depressive illness: Evidence for a susceptibility gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 91:5918–5921, 1994.

44. O.C. Stine, J. Xu, R. Koskela, F.J. McMahon, M. Gschwend, C. Friddle, et al. Evidence for linkage of bipolar disorder to chromosome 18 with a parent-of-origin effect. American Journal of Human Genetics 57:1384–1394, 1995.

45. F.J. McMahon, P.J. Hopkins, J. Xu, M.G. McInnis, S. Shaw, L. Cardon, et al. Linkage of bipolar affective disorder to chromosome 18 markers in a new pedigree series. American Journal of Human Genetics 61:1397–1404, 1997.

46. L.A. McInnes, M.A. Escamilla, S.K. Service, V.I. Reus, P. Leon, S. Silva, et al. A complete genome screen for genes predisposing to severe bipolar disorder in two Costa Rican pedigrees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 93:13060–13065, 1996.

47. D. Curtis. Chromosome 21 workshop. American Journal of Medical Genetics 88:272–275, 1999.

48. C. Van Broeckhoven and G. Verheyen. Report of the chromosome 18 workshop. American Journal of Medical Genetics 88:263–270, 1999.

49. F. Schuhoff, F. Bellivier, R. Jouvent, M.C. Mouren-Simeoni, M. Bouvard, J.F. Allilaire, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: Two different forms of manic-depressive illness? Journal of Affective Disorders 58(3):215–221, 2000.

50. K. D. Chang, H. Steiner, and T. A. Ketter. Psychiatric phenomenlogy of child and adolescent bipolar offspring Journal of American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry Apr 39(4):453–460, 2000.

51. P.J. Alexander and R. Raghavan. Childhood mania in India. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36(12):1650–1651, 1997.

52. G.S. Sachs, C.F. Baldassano, C.J. Truman, and C. Guille. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with early-and late-onset bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157(3):466–468, 2000.

53. J. Biederman, R. Russell, J. Soriano, J. Wozniak, and S.V. Faraone. Clinical features of children with both ADHD and mania: Does ascertainment of source make a difference? Journal of Affective Disorders 51(2):101–112, 1998.

54. D.A. Regier, M.E. Farmer, D.S. Rae, B.Z. Locke, S. J. Keith, L.L. Judd, et al., Comorbidity of mental disorders with drug and alcohol abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. Journal of the American Medical Association 264:2511–2518, 1990.

55. M. Tohen and F. Goodwin. Epidemiology of Bipolar Disorder. In: M.T. Tsuang, M. Tohen, and G. E.P. Zahner, eds., Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Wiley-Liss: New York, pp.301–317, 1995.

56. J.E. Helzer, A Burnam, and L.T. McEvoy. Alcohol abuse and dependence. In: L.N. Robins and D.A. Regier, eds. Psychiatric Disorders in America. Free Press: New York. pp. 81–129, 1991.

57. S.M. Strakowski and M.P. DelBello. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review Mar;20(2):191–206, 2000.

58. M.M. Weissman, M.L.Bruce, P.J. Leaf et al. In: L.N. Robins and D.A. Reiger, eds. Psychiatric Disorders in America. Free Press: New York, pp. 53–81, 1991.

59. S. Sethi and R Khanna. Phenomenology of mania in Eastern India. Psychopathology 26:274–278, 1993.

60. J.C. Robb, L.T. Young, R.G. Cooke, R.T. Joffe. Gender differences in patients with bipolar disorder influence outcome in the medical outcomes survey (SF-20) subscale scores. Journal of Affective Disorders 49(3):189–193, 1998.

61. J. Angst. The course of affective disorders, II: Typology of bipolar manic-depressive illness. Archiv fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 226:65–73, 1978.

62. L. Tondo and R.J. Baldessarini. Rapid cycling in women and men with bipolar manic-depressive disorders American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1434–1436. 1998.

63. P. Roy-Byrne. R.M. Post, T.W. Uhde, T. Porcu, and D. Davis. The longitudinal course of recurrent affective illness: Life chart data from research patients at the National Institute of Mental Health Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement 317:5–34, 1985.

64. J. Wozniac, J. Biederman, K. Kiely, J.S. Ablon, S.V. Faraone, E. Mundy, et al. Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:867–876, 1995.

65. T. Shiratsuchi, N. Takahashi, T. Suzuki, and K. Abe. Depressive episodes of bipolar disorder in early teenage years: Changes with increasing age and the significance of IQ. Journal of Affective Disorders 58(2):161–166, 2000.

66. D.J. Miklowitz and M.J. Goldstein. Bipolar disorder: A family-focused treatment approach. The Guilford Press: New York, 1997, p. 36.

67. J. Angst, W. Felder and R. Frey. The course of unipolar and bipolar affective disorders In: M Schou and E. Stromgren, eds. Origin, prevention and treatment of affective disorders. New York: Academic Press, p. 20, 1979.

68. G. Winokur, W. Coryell, J.S. Akiskal, J. Endicaott, M. Keller, and T. Mueller. Manic-depressive (bipolar) disorder: The course in light of prospective ten-year follow-up of 131 patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:102–110, 1994.

69. F.K. Goodwin and K.R. Jamison. The natural course of manic-depressive illness. In: R.M. Post and J.C. Ballenger, eds. Neurobiology of mood disorders. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, pp. 20–37, 1984.

70. T. Silverstone and S. Romans-Clarkson. Bipolar affective disorder: Causes and prevention of relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry 154:321–335, 1989.

71. M.J. Gitlin, J. Swendsen, T.L. Heller, and C. Hammen. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1635–1640, 1995.

72. M.T. Compton and C.B. Nemeroff. The treatment of bipolar depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(9):57–67, 2000.

73. P.E. Keck Jr, S.L. McElroy, S.M. Strakowski, C.A. Soutullo. Antipsychotics in the treatment of mood disorders and risk of tardive dyskinesia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(Suppl 4):33–38, 2000.

74. S. Mukherjee, A.M. Rosen, G. Caracci, and S. Shukla. Persistent tardive dyskinesia in bipolar patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:342–346, 1986.

75. M.A. Frye, T.A. Ketter, L.L. Altshuler, K. Denicoff, R.T. Dunn, T. A. Kimbrell, et al. Clozapine in bipolar disorder: Treatment implications for other atypical antipsychotics. Journal of Affective Disorders 48:91–104, 1998.

76. M.A. Brotman, E.L. Fergus, R.M. Post, G.S. Leverich. High exposure to neuroleptics in bipolar patients: A retrospective review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(1):68–72, 2000.

77. M. Srisurapanont, L.N. Yathan, and A.P. Zis. Treatment of acute bipolar depression: A review of the literature Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 40(9):533–544, 1995.

78. J.C. Masters. When lithium does not help: The use of anticonvulsants and calcium channel blockers in the treatment of bipolar disorder in the older person. Geriatric Nursing 17(2):75–78, 1996.

79. J. Cookson. Lithium and other drug treatments for recurrent affective disorder In: S. Checkley, ed. The Management of Depression. Blackwell, U.K., 1998.

80. A.Coppen and M.T. Abou-Saleh. Lithium in prophylaxis of unipolar depression. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 76:297–301, 1983.

81. P. Vestergaard. Clinically important side effects of long term lithium treatment: A review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 305:1–36, 1983.

82. P.E. Keck Jr. and S.L. McElroy. Outcome in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16(2 Suppl):15S–23S, 1996.

83. L. Tondo, K.R. Jamison, and R.J. Baldessarini. Effect of lithium maintenance on suicidal behavior in major mood disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 836:339–351, 1997.

84. P. Vestergaard, A. Adisen, and M. Schou. Clinically significant side effects of lithium treatment: A survey of 237 patients in long term treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica 62:193–200, 1980.

85. L. Tondo and R.J. Baldessarini. Reduced suicide risk during lithium maintenance treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(9):97–104, 2000.

86. G. Johnson. Lithium. Medical Journal of Australia 141:595–601, 1984.

87. L.S. Cohen, J.M. Friedman, J.W. Jefferson, E.M. Johnson, and M.L. Weiner. A reevaluation of risk of in utero exposure to lithium. Journal of the American Medical Association. 271:146–150, 1994.

88. S. M Long. Lasting neurological sequelae after lithium intoxication. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica 70:594–602, 1984.

89. A.J. Frances, D.A. Kahn, D. Carpenter, J.P. Docherty, and S.L. Donovan. The Expert Consensus Guidelines for treating depression in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(Suppl 4):73–79, 1998.

90. G.L. Zornberg, H.G. Pope. Treatment of depression in bipolar disorder: New directions for research Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:397–408, 1993.

91. A.R. Dehpour, E.S. Emamian, S.A. Ahmadi-Abhari and M Azizabadi-Farahant. The lithium ratio and the incidence of side effects. Progress in NeuroPsychopharmacological & Biological Psychiatry 22:959–970, 1998.

92. R. M. Post, G. S. Leyerich, A. S. Rosoff, and L. L. Altshuler. Carbamazepine prophylaxis refractory affective disorders: A focus on long-term follow-up. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology Oct; 10(5):318–327, 1990.

93. Okuma, A. Kishimoto, K Inoue et al. Anti-manic and prophylactic effects of carbamazepine on manic depressive psychosis: A preliminary report. Folia Psychiatric Neurology, Japan 283–297, 1973.

94. D.G. Folks, L.D. King, S.B. Dowdy, W.M. Petrie, R.A. Jack, J.C. Koomen, B.R. Swenson, and P. Edwards. Carbamazepine treatment of selected affectively disordered inpatients American Journal of Psychiatry 139:115–117, 1982.

95. Y. Kwamie, E. Persad, and H. Stancer. The use of carbamazepine as an adjunctive medication in the treatment of affective disorders: A clinical report. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 29:605–608, 1984.

96. R.M. Post, T.W. Uhde, P.P. Roy-Byrne, and R.T. Joffe. Correlates of antimanic responses to carbamazepine. Psychiatric Research 21:71–84, 1987.

97. K.D. Denicoff, E.E. Smith-Jackson, E.R. Disney, S.O. Ali, G. S. Leverich, and R.M Post. Comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium, carbamazepine, and the combination in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:470–478, 1997.

98. L. Banfi, M. Ceppi, M. Colzani, F. Guzzini, R. Morena, and P. Novati. [Carbamazepine-induced agranulocytosis. Apropos of 2 cases]. Recenti Progressi in Medicina [Article in Italian] Oct;89(10):510–513, 1998.

99. D.W. Kaufman, J.P. Kelly, J.M. Jurgelon, T. Anderson, S. Issaragrisil, B. E. Wiholm, et al. Drugs in the aetiology of agranulocytosis and aplastic anaemia. European Journal of Haematology supplement 60:23–30, 1996.

100. H. Askmark and B.E. Wilholm. Epidemiology of adverse reactions to carbamezepine as seen in a spontaneous reporting system. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica Feb;81(2):131–140, 1990.

101. J. R. Calabrese and M. J. Woyshville. A medication algorithm for treatment of bipolar rapid cycling? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56(3):11–18, 1995.

102. E. Thisted and F. Ebbeson. Malformations, withdrawal manifestations and hypoglycaemia after exposure to valproate in utero. Archives of Diseases of Childhood 69:288–291, 1993.

103. N. Poolsup, A. Li Wan Po, and H.R. de Oliveira. Systematic overview of lithium treatment in acute mania. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 25(2):139–156, 2000.

104. J. Novacek and R. Raskin. Recognition of warning signs: A consideration for cost-effective treatment of severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49(3):376–378, 1998.

105. N.J. Gogtay, N.S. Kshirsagar, and S.S. Dalvi. Therapeutic drug monitoring in a developing country: An overview. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 48(5):649–654, 1999.

106. R.S. Murthy, personal communication, 2000.

107. B.O. Rothbaum and M.C. Astin. Integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for bipolar disorder Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(Suppl 9):68–75, 2000.

108. D.J. Miklowitz and L.B. Alloy. Psychosocial factors in the course and treatment of bipolar disorder: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108(4):555–557, 1999.

109. K.C. Wilson, M. Scott, M Abou-Saleh, R. Burns, and J.R. Copeland. Long-term effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy and lithium therapy on depression in the elderly. British Journal of Psychiatry 167(5):653–658, 1995.

110. N.A. Huxley, S.V. Parikh, and R.J. Baldessarini. Effectiveness of psychosocial treatments in bipolar disorder: State of the evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8(3):126–140, 2000.

111. E.M. Van Gent. Follow-up study of 3 years group therapy with lithium treatment. [Article in French] Encephale 26(2):76–79, 2000.

112. D. Dudek and A. Zieba. Development and application of cognitive therapy in affective disorders [Article in Polish] Psychiatria Polska 34(1):81–88, 2000.

113. S.A. Hlastala, E. Frank, A.G. Mallinger, M.E. Thase, A.M. Ritenour, and D.J. Kupfer. Bipolar depression: An underestimated treatment challenge. Depression and Anxiety 5(2):73–83, 1997.

114. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder American Journal of Psychiatry 151(Suppl 12):1–36, 1994.

115. N.A Reilly-Harrington, L. B. Alloy, D.M. Fresco, and W.G. Whitehouse. Cognitive styles and life events interact to predict bipolar and unipolar symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108:567–578, 1999.

116. T.L. Simoneau, D.J. Miklowitz, J.A. Richards, R. Saleem, and E.L. George. Bipolar disorder and family communication: Effects of a psychoeducational treatment program. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108:588–597, 1999.

117. E. Frank, Swartz H.A., A.G. Mallinger, M.E. Thase, E.V. Weaver, and D.J. Kupfer. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: Effects of changing treatment modality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108(4):579–587, 1999.

|

Summary of Findings: Depression in Developing Countries

|