3

How People Learn

An important objective of the conference was to review the contributions that research has made to education and to examine its potential for playing an even greater role in narrowing achievement gaps and helping all students reach high standards. An organizing premise was that research is one of the most important tools available to ensure that education policies and practices are thoughtful and effective. Yet the great potential of research to improve education has yet to be realized (National Research Council, 1999d:11; Shaw, 1997:8).

This principle was articulated by the many speakers at the conference and preconference workshops who underscored the importance of research-based reforms. Phyllis Hunter described her collaboration with researcher Barbara Foorman in implementing a research-based reading program in Houston and later throughout the State of Texas. Like several other speakers, she emphasized that the success of research-based reforms depends on developing a partnership among researchers, administrators, and teachers that is based on mutual respect. Like other speakers, she emphasized the importance of a two-way flow of information between the reformer or change agent and teachers. “Professional development is often based on fads, accountability pressure and is often coercive, so teachers just freeze up. . . . The lynch pin of any initiative to increase student achievement is a knowledgeable and caring teacher.”

This chapter discusses the cognitive dimensions of learning and the immediate social contexts in which learning occurs. Much of the information presented is drawn from the presentations of Barbara Bowman,

Catherine Snow, and John Bransford, especially their discussions of the published findings of the National Research Council (NRC) committees that each chaired (National Research Council, 1998a, 1998b, 1999a, 1999b, 2000a, 2001b). The chapter also draws on the presentation of child development researcher Craig Ramey.

Specifically, the chapter presents research findings on human learning from the perspective of cognitive science; early childhood development and the characteristics of social environments that effectively promote it; and the teaching and learning of early reading skills. First presented are principles of learning as discussed by John Bransford. These general principles are derived from research in cognitive science and summarized in How People Learn (National Research Council, 1998a). These general principles of learning are applicable across the life span and inform material presented later in the chapter on early childhood development and education and on how children learn to read. The chapter concludes with a discussion of a theoretical model of school learning and instructional capacity developed by David Cohen et al. (2001) and presented by Cohen in a preconference workshop. This model provides a helpful conceptual and theoretical framework for uniting the cognitive and developmental perspectives on learning presented in this chapter with the social and cultural perspectives that are the focus of Chapter 4.

This review of research on learning and education, including its cognitive and social dimensions, necessarily is highly selective. Research discussed by conference presenters and reported here highlights findings on the above-mentioned topics of particular relevance to the conference themes. The reports of the NRC committees that Bransford, Bowman, and Snow chaired or cochaired are themselves selective summaries of major findings on learning, the development of young children, and early reading about which there is broad scientific consensus. For a fuller discussion of these topics, the reader is directed to the published committee reports and to other references cited in those reports and in this volume.

COGNITION AND LEARNING

The Science of Learning

According to John Bransford, learning research can be an important tool for educators who want to help many more students develop the kinds of advanced intellectual skills that W.E.B. DuBois long believed were the province of only “the talented tenth.” Although research from the cognitive sciences on learning is not the sole answer for closing the achievement gap and bringing all students to high academic standards, it can be considered a good starting point.

Cognitive science originated in the late 1950s when the complexity of human behavior and its causes was becoming increasingly apparent. At that time, new experimental methodologies, theories, and conceptual tools were emerging that enabled scientists to transcend both the nonscientific formulations of philosophy and the empiricist limitations of the then-dominant behaviorist model. The new discipline of cognitive science facilitated for the first time the formulation and testing of scientific theories of mental functioning, including the processes of learning (National Research Council, 1998a:8).

|

New ideas about ways to facilitate learning—and about who is most capable of learning—can powerfully affect the quality of people’s lives. At different points in history, scholars have wor ried that formal educational environments have been better at selecting talent than developing it. National Research Council, 2000a:5 |

A focus on learning with understanding is the hallmark of much research in cognitive science (e.g., Piaget, 1978; Vygotsky, 1978). The research focus on learning with understanding that emerged in the latter half of the 20th century is fortuitous, given education’s evolving role in preparing young people for full participation in the emerging technology- and information-intensive economy. Schooling in the early 20th century was mostly limited to the “three Rs”—reading, writing and ’rithmetic—and certain essential facts considered important for citizenship and functioning in an economy dominated by agriculture and manufacturing. By the end of the 20th century, the ability to think and read critically, to express oneself in a logical and persuasive manner, and to solve complex problems involving science and mathematics had become the new educational standard. As noted by Herbert Simon, the meaning of “knowing” had shifted during the course of the 20th century from being able to remember and recite information to having the skills needed to access and use it (National Research Council, 2000a; Simon, 1996).

Personalization and Learning for Understanding

Accessing and using information requires more than the ability to remember seemingly unrelated facts that teachers deem important for reasons unknown to the student. It requires that one be able to juxtapose—to put together in new ways—information from various sources to

address problems or issues at hand. In other words, it requires learning for understanding and that students be able to integrate school learning into the fabric of their own lives. Learning for understanding, in turn, means that students are personalizing the lessons they are taught in school.

Each student brings to school understandings and beliefs derived from his or her own idiosyncratic experiences that, in turn, are shaped by socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, gender, religious, and other social identities that come into play in various social contexts. A premise of learning science is that humans are goal-directed agents who actively seek information from the environment (National Research Council, 1998a:10). How students seek out and interpret information at school and whether they make the mastery of academic lessons an important personal goal is profoundly affected by how preexisting knowledge and interests from the home and community environments mesh with school-based meanings and identities. Information is transmitted to students at school both through formal instruction and through informal interaction with teachers and classmates. Lessons learned at school may be essentially consistent with lessons learned at home and in one’s community. Alternatively, school lessons may be rather different from lessons learned at home and in the community, or perhaps even dissonant with the meaning system, interests, and identities of home, peers, or community.

|

Learning research suggests that there are new ways to introduce students to traditional subjects, such as mathematics, science, history, and literature, and that these new approaches make it possible for the majority of individuals to develop a deep under standing of important subject matter. National Research Council, 2000a:5 |

Bransford noted that people are inherently motivated to solve problems and to maintain a sense of competence in activities that are important to them (National Research Council,1998a:48; White, 1959). Teachers who respect and make an effort to understand the interests of their students make it easier for those students to appreciate the relevance of lessons taught at school (Garcia, 1999). Similarly, teachers who respect and draw on the knowledge, beliefs, and interests of their students help them feel that school is a place where they belong. Bransford cited Robert Moses’ Algebra Project as a good example of an instructional strategy that draws on these principles.

The Algebra Project curriculum links mastery of algebra to the civil rights struggle. The successes of the civil rights movement cleared obstacles out of the pathway from poverty to the middle class. A message of the Algebra Project is that to walk down that pathway, students must demand a quality education and then take full advantage of the learning opportunities it offers. Mastering algebra in the 8th or 9th grade is seen as the unavoidable gateway to a college preparatory curriculum. Part of the project’s methodology is to help students make the connection between their personal experiences and the struggle for civil rights, and then to link what they have learned from visiting civil rights historical sites and related hands-on experiences to mathematical constructs. The project has been successful in helping some low-income minority students who otherwise might not understand the relevance of algebra to their lives (Moses and Cobb, 2001).

If teachers make the effort to connect their lessons with the preexisting knowledge base of their students, they increase the probability that the students will master the lessons. If this occurs, students are likely to feel that they are respected and competent actors in the social environment of the school. This reinforces their personalization of school lessons, their identification with learning objectives, and motivation to establish a sense of competency in relation to the curricula.

This strategy is consistent with an important tenet of learning science—that people construct new knowledge and understandings based on what they already know and believe (National Research Council, 1998a:10). The greater the social and cultural distance between the school environment and the home and community environments, the more difficult it is for students to draw on their preexisting funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1993) as they work to understand school lessons.

Learner-Centered Teaching

Effective teachers have both the interest and the skills needed to link the lessons and culture of the school with those of the home—to tie school lessons with the preexisting knowledge base of the student. That is, they have the ability to make their classrooms and their teaching learner centered (National Research Council, 1998a:122). Engaging parents and other caregivers as partners in their children’s education is one obvious strategy to do this.

Bransford used the term constructivism to refer to a tenet of learning theory that all learning necessarily involves the use of existing knowledge to construct new knowledge. The term also is used, however, to describe a pedagogical theory emphasizing active learning, discovery, and problem solving rather than direct instruction and lecturing. According to

Bransford, equating these two usages of constructivism is a common misunderstanding of learning theory.

Certainly, if a school provides instruction through active learning and discovery (e.g., doing a science experiment) students are constructing knowledge. However, as described by Bransford, the student who listens to a lecture also is constructing knowledge as he or she tries to make sense of what is being said by integrating the new information presented into his or her preexisting knowledge base. A student who attends to a teacher who is giving direct instruction is constructing meaning, no less than the student who is engaged in discovery learning (Adams and Englemann, 1996).

|

Transfer from school to everyday environments is the ultimate purpose of school-based learning. National Research Council, 2000a:78 |

Efforts to teach children about the concept of mass and the density of matter can quickly illustrate why active learning sometimes is preferable to lecturing. However, there are situations in which teaching by telling may be more effective (National Research Council, 1998a:10, 11). In either case, teachers who provide learner-centered instruction will take into consideration the preconceptions that students bring to the learning situation to help them integrate new information with the old.

Knowledge-Centered Teaching

Bransford emphasized that providing instruction that is learner centered is not enough. To use a metaphor from How People Learn, “if good teaching is conceived as constructing a bridge between the subject matter and the student, teachers must keep a watchful eye on both ends of the bridge” (National Research Council, 1998a:124). That is, instructional environments should be knowledge centered as well as learner centered. Teachers who are learner centered work to understand what students know, care about, are able to do, and want to do. Knowing this, they are better able to establish and maintain the flow of discipline-based knowledge across “the bridge.” But research has shown that thinking and problem solving require mastery of well-organized bodies of knowledge to support planning and strategic thinking (National Research Council, 1998a:9). Learner-centered and knowledge-centered teaching intersect when awareness of students’ preconceptions are used as a starting point

to gain a deep understanding of subject matter and eventually to retrieve and apply relevant concepts in a variety of problem-solving situations. For the latter to occur, it is important that students’ retrieval of information not be contingent on the context in which it was learned. Appropriately selecting and applying knowledge in a variety of problem-solving contexts require understanding the relationships among ideas within and between domains of knowledge.

In knowledge-centered learning environments, the content, organization, and sequencing of curricula are carefully constructed to facilitate students’ development of a deep understanding of the subject matter. Knowledge-centered educators organize instruction in a manner that helps learners to understand the inherent structure of the knowledge domains and disciplines that are taught. Standards that have been proposed or established in such areas as mathematics, science, and reading help to define the knowledge and competencies that students should acquire and the instructional strategies that will help them develop a deep understanding of it (National Research Council, 1996, 1999b; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1989; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2000). To extend Bransford’s metaphor, knowledge-centered instruction entices students to cross the bridge that leads from their familiar, comfortable intellectual environment to new domains of knowledge.

Assessment-Centered Teaching

In addition to being learner centered and knowledge centered, Bransford argues that learning environments also should be assessment centered. What students are learning should be assessed frequently to measure whether they understand the relationships among ideas presented, not just how well they have memorized facts. In other words, students should be frequently tested and their learning evaluated by other means to measure whether they are learning for understanding. Frequent assessment of progress toward mastery of explicit learning objectives provides valuable feedback to both teacher and student. These kinds of assessments (called formative assessments) provide the teacher with valuable real-time information to use in modifying instructional plans to better accomplish learning objectives.

Frequent formative assessments also provide students with valuable feedback that can help them to reflect on their learning strategies and to modify them if necessary. In other words, they help students to become metacognitive. Being metacognitive means that they can reflect on the soundness of their reasoning and make changes in thought processes as necessary. This is essential if they are to successfully adapt what they

have learned in school to address problems in everyday settings. According to How People Learn, this, after all, is the ultimate goal of schooling (National Research Council, 1998a:66).

|

Increasing the amount of information available to teachers about what is working would be a very helpful thing to do. Technology can start making this happen. Having well-aligned goals and frequent formative assessments are the most important things [that could be done to improve student learning]. * * * Doing frequent formative assessments is the single most impor tant thing I know for helping teachers see which kids are making the kind of progress you expect and which kids need extra help. Increasing the information that is available to teachers and par ents to make decisions about what is working would be a very helpful thing. John Bransford, Chair, Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning |

Community-Centered Teaching

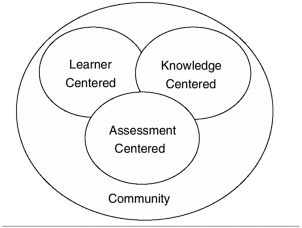

Finally, learning environments also should be community centered. Ideally, students, teachers, and other interested parties have a common commitment to learning and high standards that causes the behavioral norms of school and community to reinforce each other. This ideal situation makes it easier for students to understand the importance of school learning in very concrete ways—to personalize it and integrate it into the fabric of their lives. That school-community ties always are important is clear, especially when one considers the small amount of time that students spend in school compared with community settings. Activities in homes, community centers, and after-school clubs can have important effects on students’ academic achievement (National Research Council, 1998a:142). Schools that make deliberate plans to improve their ties to the community create more favorable learning environments for their students (Comer, 1980, 1989). Figure 3-1 depicts the overall concept.

Children’s capacity for abstract thinking increases as they grow older and, although important throughout the life span, the relevance of learning for the satisfaction of immediate personal and emotional needs gradually decreases. Accordingly, knowledge-centered instructional strategies assume greater importance as students go through elementary and sec-

FIGURE 3-1 Perspectives on Learning Environments. SOURCE: Bransford et al., 1998.

ondary school. Personalization and learner-centered instruction are most essential during early childhood, when children’s socioemotional developmental needs are the most salient (National Research Council, 2000a:79-113).

YOUNG CHILDREN: EAGER TO LEARN

In 1965, fewer than 20 percent of young children were enrolled in early childhood education. By 1997, 65 percent of 4-year-olds and 40 percent of 3-year-olds attended preschool. These figures strongly suggest that preschool enrollments are large, growing, and increasingly important in their potential contribution to academic achievement (National Research Council, 2001b:25). Whether at home or in preschool, the early learning experiences of young children have a profound effect on their later education.

For many years, the federal government has played an important role in helping young children get ready for school through its support of child health and nutrition programs and most especially through its sponsorship of Head Start. Since the 1990 launch of the first Bush administration’s America 2000 initiative, having all children start school ready to learn has been at the top of the list of federal education priorities. This continued under the Clinton administration’s Goals 2000 program. Yet much more can be done to improve the school readiness of many preschool children, as discussed by Barbara Bowman and Craig Ramey in Eager to Learn: Educating Our Preschoolers and in From Neuron to Neighbor-

hoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (National Research Council, 2000c; 2001b). According to Bowman and Ramey, we know how to improve the development and school readiness of young children. The question is whether the resources and political will can be marshaled to do it.

Ready to Learn?

The U.S. Department of Education’s Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99, presents data on the cognitive development and learning of a nationally representative sample of young children. As outlined in detail by Zill and West (2000) and discussed by Bowman, school readiness skills are far from evenly distributed across racial/ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. Bowman noted that many sources have documented that both individual and group differences in learning achievement already exist when children first enroll in school. Without intervention, these differences tend to persist into the later grades. Gaps in early academic skills statistically explain much of the achievement differential apparent years later in secondary school and beyond (Phillips et al., 1998b). Both Bowman and Ramey argued that much could and should be done during the preschool years to counteract this by working to ensure that students from all backgrounds enter school on an even footing.

Eager to Learn (National Research Council, 2001b) focused on three questions:

-

What is it about young children that defines the parameters for thinking about early learning?

-

What should children learn and how should they be taught?

-

What public policies are needed to ensure that all children have the opportunity to learn what they need to be educationally successful?

Development and Learning

The Eager to Learn title refers to one of the committee’s most important findings—that young children are naturally predisposed to learn. Cognitive, social-emotional, and physical development are complementary and mutually supportive. They occur naturally during the preschool years, given the active involvement of caring, knowledgeable adults. For this reason, Bowman reported, the study found the common semantic

distinction between child care and child learning (preschool) environments to be misleading and unfortunate (National Research Council, 2001b:6-7). She argued that learning, especially learning that is related to school readiness, should be an explicit emphasis of all early childhood settings. This is especially true for settings that serve young children who are most at risk of school failure.

The most effective teachers of preschool children are adults who know and care about them, who recognize the developmental milestones that each child has passed, and who use that knowledge to guide children through new learning and to the next developmental milestones for which they are ready. That is, effective preschool teachers know how to assist each child to master those tasks that are within his or her zone of proximal development (National Research Council, 2001b: 42-43; Vygotsky, 1978; Rogoff, 1990).

|

[A]dequate care involves cognitive and perceptual stimulation and growth, just as adequate education for young children must occur in a safe and emotionally rich environment. National Research Council, 2001b:33 |

Given a safe and emotionally rich environment in which to grow and develop, Bowman stated all children have a similar capacity to learn— although what they learn depends on what the environment has to offer. Not all environments, however, are equally good at helping children learn. When there are too few resources, or when children experience overwhelming doses of hunger, disease, danger, abuse, or neglect, learning is compromised. Poverty is one of the major results of deficient environments. A large proportion of children—more than one-third of all black and Hispanic children—come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and many of these families are stressed by poverty.

Child Development and School Readiness

According to Bowman, just because children come from low-income families, it should not be assumed that their environment necessarily deprives them of the capacity to learn. Most low-income and minority children flourish despite hardships and can learn well—but often not in school. This is because school achievement requires a particular kind of learning. In school, children are taught to read, write, do arithmetic, sit in chairs at desks, not talk very much, line up, make friends, and do what

the teacher says. Some children learn early things that help prepare them for school, while other children learn different things that may not be helpful in school. For example, children who gain experience at home or in preschool with counting, distributing, and reflecting about quantity are likely to be successful with arithmetic. Other children, such as those who are very active physically, may be at a disadvantage in school. One child’s parent may feel uncomfortable in school and stay away, while another child’s parent may feel more comfortable in school and may get involved. Thus, the preschool experiences of some children help them become better prepared for school than others. Children who are not well prepared when they start school often fail. Preschools that are successful in their efforts to reach out and involve parents may be better positioned to understand and use children’s existing funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1993) as a foundation for building their academic skills.

Children at risk for school failure come from all kinds of families but disproportionately have low incomes and minority status. Their poor academic performance begins early, and the achievement gaps widen as they progress through the school years. While skin color has nothing to do with how people learn, Bowman noted, people continue to talk about race because historically it has been the basis for discrimination and poverty, and the color issue continues to be one of the hardest ones for Americans to come to grips with.

Respect and Acceptance

A prejudicial environment is created at school when a child’s typical language and behavior, which are acceptable at home, are considered unacceptable or inadequate at school. This situation tends to erode children’s self-confidence and undermines self-esteem—two attributes that are essential for learning. Commenting on the behavioral and learning implications of this, Bowman stated, “Just as many of us would do if we had to build an igloo, live in a jungle, or go to sea, children just shut down, or learn not to care because they do not know the things they are supposed to know.” This can happen at any time from preschool through high school, but the danger of it occurring is particularly acute during the preschool years. Preschools should work to ensure that culturally and linguistically diverse children are accorded the same respect and advantages as others. If they can accomplish this, preschools are more likely to play an important role in giving children the kind of solid foundation they need to excel in school.

Transactional Experiences Conducive to Learning and Development

Craig Ramey discussed at the conference a number of careful studies of high-quality preschool programs, including the Abecedarian Project, Project CARE, and the Infant Health and Development Program (Ramey and Ramey, 1998b). Distilling findings from more than 1,000 scientific studies, he discussed the following seven transactional experiences that children have with adult caregivers, including parents and preschool teachers. According to Ramey, all seven are important to children’s learning, development, and school readiness. Research has shown that children who:

-

are encouraged to explore,

-

are mentored in basic skills,

-

have their developmental advances celebrated,

-

are guided in rehearsing and extending newly developed skills,

-

are protected from inappropriate disapproval and punishment,

-

are communicated with richly and responsibly, and

-

whose behavior is lovingly guided and limited at times

are children who are more competent when they enter first grade (Ramey and Ramey, 1998b). The evidence from studies of the above-mentioned programs and from many others makes it clear that high-quality preschool programs that emphasize these kinds of interactions between adults and children produce significant cognitive and social developmental benefits—especially for those children who are most at risk. Although studies show that measurable cognitive and social program effects often fade and sometimes disappear as children progress through elementary and secondary school, some programs appear to produce long-lasting effects, including lower dropout rates and delinquency rates. The size and duration of program effects appear to be related to preschool program quality, age at entry, length of time in the program, and the quality of subsequent educational services (Ramey and Ramey, 1998b; Campbell and Ramey, 1994).

Caring and Well-Educated Teachers

Because of the need to ensure that young children, especially the most at risk, are learning the early literacy and numeracy skills that they will need to succeed in school, Eager to Learn recommends that all preschool teachers have at least a bachelor’s degree (National Research Council, 2001b:13). As Bowman put it, “Adults help [children learn] by knowing when to scaffold a new skill and when to back off and let children do

things for themselves. In other words, the adult role is critical, and the more she or he knows about children, how they learn, and how to support their learning, the better children will learn.”

For example, posting the alphabet on the wall and singing the alphabet song are not likely to enable children to learn how letters and sounds map to each other or how the sounds represented by letters are combined into words. These simple teaching devices are unlikely to help children to construct the various components of the reading process, from verbal language, vocabulary, phonemics, and phonetics to reading for meaning. Having a preschool teacher who is skilled in helping children—especially the most disadvantaged—learn these skills is essential if progress is to be made toward the goal of having all children start school ready to learn. Preschoolers need to be well on their way to learning these and other sophisticated tasks as they make the transition to first grade.

Bowman noted that there is a considerable gap between the kind of education and training that Eager to Learn concludes that teachers should have to do a competent job and what currently exists. This gap is partly due to the belief that preschool children are too young to need well-educated teachers. Yet the research consistently correlates teacher education, especially in child development and education, with children’s improved performance in critical domains for school achievement (National Research Council, 2001b:261-276). Compounding the problem are low salaries that make recruiting college graduates to work as preschool teachers extremely difficult.

PREVENTING READING DIFFICULTIES IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Early Reading: A Foundational Skill

Building strong reading skills beginning in early childhood is the foundation on which nearly all subsequent school-based learning is built. Yet many children—especially those who are black, Hispanic, or American Indian, come from low-income families, or live in high-poverty neighborhoods or attend high-poverty schools—are at great risk of not acquiring essential early reading skills (National Research Council, 1998b:96-98). Catherine Snow, who chaired an NRC study on preventing reading difficulties in young children, discussed the nature and extent of reading difficulties in young children, drawing on the study report in her presentation. While noting that the practical challenge of preventing reading difficulties in young children is enormous, she argued that this is one educational problem for which research has shown that there is a viable solution.

The Risk of Falling Behind Early

Academic success, conservatively defined as high school graduation, can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by knowing how well a student reads at the end of third grade. The student who does not read at least moderately well by the end of third grade has a lesser chance of graduating from high school (National Research Council, 1998b: 21; Slavin et al., 1994). According to the National Assessment Governing Board (2000), 4th graders with basic reading skills are able to demonstrate an understanding of the overall meaning of what they read. They can make relatively obvious connections between the text and their own experiences and extend the ideas in the text by making simple inferences. On the 1998 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), 64, 60, and 53 percent of black, Hispanic and American Indian 4th graders, respectively, lacked basic reading skills. This compares with 27 percent of white 4th graders and 31 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders who scored below basic (National Center for Education Statistics, 1999a; National Research Council, 1998b:96-98).

The concentration of poor readers in certain ethnic groups and in poor, urban neighborhoods and rural towns is a matter of great concern (National Research Council, 1998b:327-328).

The educational careers of…[these] children are imperiled because they do not read well enough, quickly enough, or easily enough to ensure comprehension in their content courses in middle and high school. Although some men and women with reading disability can and do attain significant levels of academic and occupational achievement, more typically poor readers, unless strategic interventions in reading are afforded them, fare poorly on the educational and subsequently the occupational ladder.

Problems in Early Identification and Treatment

Drawing on the report, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children, Snow argued that early identification, coupled with effective intervention, is essential to any effective strategy to address this problem. It is estimated that more than 2 million children—approximately 3.5 percent of all U.S. schoolchildren—have been diagnosed with reading disabilities and are enrolled in special education programs for that reason. Students identified as reading disabled constitute approximately 80 percent of all children receiving special education services.

Because of the diagnostic criteria commonly used by federally supported special education programs, many children are not identified as having a reading disability until 3rd or 4th grade. By then, they typically

are lagging badly in their reading skills, which, in turn, increasingly causes them difficulties in other subjects. Without effective intervention, this situation saps children’s natural enthusiasm and eagerness to learn (National Research Council, 2001b) and can lead to a downward spiral of demoralization and school failure.

Reading Benchmarks

Snow argued that one step toward preventing this from occurring is for preschool, kindergarten and early elementary school educators to frequently assess (i.e., on a monthly if not weekly basis) their children’s prereading and reading skills in relation to relevant benchmarks. Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children established two sets of developmental accomplishments—one for children from birth to age 3, and one for 3- and 4-year-olds. It also includes four lists of benchmark reading accomplishments for children from kindergarten through grade 3 (National Research Council, 1998b:61, 80-83; 1999b:15-125). These benchmarks outline dimensions or types of skills that contribute to good reading.

Children’s proficiency in these skills and, indeed, in reading itself tend to be normally distributed in the population. In assessments of reading skills, as is true with other normally distributed phenomena, such as blood pressure, there are no categorical markers that differentiate normalcy from disability or pathology (National Research Council, 1998b:87-93). With reading difficulties, as with hypertension, scores at the tail end of the normal distribution are interpreted to signify the need for remedial action. Although the reading difficulties of some children have clearly identifiable conditions associated with them—e.g., cognitive deficiencies, hearing impairment, early language impairment, attention deficit (pp. 100-108)—in most cases there are no clear causes for reading difficulties (pp. 85-96). For this reason, Snow suggested, educators should recognize that reading is a skill that simply is more difficult for some children to acquire than for others. Rather than categorize or label most children who are poor readers as dyslexic or reading disabled, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children recommends that they be provided with high-quality reading support beginning in preschool (pp. 135-274). The quality of early reading instruction in classrooms serving at-risk children should be at least equal to, if not better than that available to children from more advantaged backgrounds. The report recommends that schools that enroll many at-risk children receive extra funding to pay for instructional programs that have been proven successful, reduce class size, hire the most capable teachers, and purchase a sufficient quantity of high-quality books and other materials (National Research Council, 1999b:133-134).

Snow commented on how her committee intended for its reading

benchmark lists to be used. To illustrate, she noted that the following items were included among the benchmark reading development accomplishments for 4-year-olds:

-

showing an interest in story books,

-

telling a brief story,

-

recounting an event in his or her own words, and

-

knowing 10 letters of the alphabet.

She added that the reading development benchmarks were not meant to be used as tests: “They weren’t meant to be the sorts of things you had to get to before you could have your fifth birthday party. They were meant to be helpful to adults in thinking about the kinds of experiences that we should be giving kids—what kids could be expected to be able to learn— not what they have to know. They can be helpful if used to judge the adequacy of reading instruction programs.”

Potential Benefits of Early Intervention

Although many Head Start programs have not yet focused or are just beginning to focus on preliteracy skills, Head Start and similar publicly funded programs serving children from low-income families typically produce significant gains (e.g., one-half of a standard deviation) in reading-related skills (National Research Council, 1998b:150). In certain small, model programs such as the Abecedarian Project, effects can be larger and longer lasting. Participants in the Abecedarian Project received enriched day care services that stressed language and cognitive development from infancy through age 5. Former participants had statistically significant gains over control subjects in their reading achievement from age 8 through 15.

|

It is not reasonable to expect children to learn how to do this difficult thing if they don’t know what it is good for; if they don’t understand that reading gives them access to the pleasure of sto ries, to information that might be useful to them; that writing gives them access to very fulfilling, useful functions like making lists so you don’t forget, labeling things, and sending off nasty letters to people who have offended you. Catherine Snow, Conference Co-Moderator |

Opportunity to Develop Enthusiasm for Reading

Rather than focus on any specific program or strategy as being superior to others, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children emphasizes broad principles for early reading instruction. One is the need for young children to have the opportunity to develop enthusiasm for learning to read and write. Snow noted the similarity between this finding and the comments of Edmund Gordon and John Bransford, both of whom emphasized the personalizing of school lessons. Reading and writing must be perceived as important or relevant in the context of children’s lives at home and in their communities. As Snow noted, “Many kids encounter real problems [in learning to read and write] but, with sufficient enthusiasm for the task, it is possible for them to persist through the difficult moments because they understand the uses and functions of written language.”

Research indicates that group differences in reading skills associated with race/ethnicity and class are not related to a lack of interest in developing literacy skills among minority and disadvantaged students or among their families (National Research Council, 1998b: 29-30; Nettles, 1997). However, the literacy experiences of children from different backgrounds have often differed. Some studies have found that although the amount of literacy-related homework done by young children with different levels of reading skills is similar, children with more advanced skills are more likely to play with books and read for pleasure (p. 31). The latter activities are more common among children from more affluent families.

Learning the Alphabetic Principle

In addition to providing young children with the opportunity to learn the pleasures and practical value of reading and writing, Snow argued that it is equally important that they learn the alphabetic principle—that written spellings systematically represent the sounds of spoken words. An early step toward learning the alphabetic principle is the development of phonological and especially phonemic awareness. Phonological awareness refers to the ability to attend to the sounds of language as well as to meaning. Phonemic awareness is the ability to divide words into individual sounds and to blend sounds into individual words. It is promoted by experiences of rhyming and sorting words by beginning and ending sounds. Singing songs and making rhymes in which the meanings change with these sorts of substitutions of sounds, syllables, and phonemes help develop these skills (National Research Council, 1999b:46).

Mastering the alphabetic principle means being able to fluently map letters to sounds and then to access the meaning of the word being read. Children who develop phonological awareness during the preschool years are less likely to have problems with 1st grade reading instruction. Deliberately teaching such skills from the preschool years into the early elementary grades is no less important than giving children the opportunity to appreciate written language by exposing them to good literature.

There is no single formula or mix of strategies that works equally well for all students in teaching sound-letter relationships, vocabulary, and comprehension. Each child needs varying amounts and kinds of knowledge and learning experiences to get started as a reader. After that, children need to acquire substantial reading experiences to build on these skills to the point at which associating meaning with written text becomes rapid and automatic. Awareness of the mechanics of reading should fade into the background as the reasons for reading are fulfilled (pp. 79, 84).

Correlates Are Not Causes

For a variety of reasons, children differ in how easily they learn to read and the age at which they acquire various prereading and reading skills. In her presentation, Snow cited a number of social correlates for the development of reading skills as well as risk factors for reading difficulties. She emphasized, however, that the correlates of reading skills should not be considered prerequisites and causation should not be attributed to the risk factors associated with reading difficulties for individual students. Snow argued that the knowledge and practice of teaching literacy skills to young children have progressed to the point at which the ability of educators to develop effective programs no longer is in doubt. A large number of programs that show impacts on reading outcomes already exist, including Success for All, described in greater detail in Chapter 6.

Knowing What to Do and How to Do It

According to Snow, effective reading programs for young children provide teachers with some “scripting” (i.e., a tightly structured instructional plan), along with effective professional development. They also have good curricula that are based on principles alluded to here and discussed in much greater detail in her study’s two volumes (National Research Council, 1998b, 1999b), more time (especially uninterrupted time) on task, instructional leadership, and a conscious effort to recruit support for reading instruction from outside the school (especially from parents).

While confident that educators have demonstrated that they know how to teach early reading skills, she was less sure about the ability of educators to develop the reading comprehension and vocabulary skills of older students. Although studies of model programs have demonstrated techniques that work well in deepening students’ reading comprehension skills and expanding vocabulary, there is little to suggest that even successful model programs are sustainable—even when taught by well-trained teachers. As Snow put it, “it is not by chance that vocabulary instruction and reading comprehension are two domains where we don’t know how to implement effective programs. It is because they involve many more unconstrained knowledge domains than does early reading instruction.”

Snow also cited as a daunting challenge the task of implementing effective early reading programs while simultaneously attempting to do the same with mathematics and science. She observed:

Do we know how to do them altogether in the same school with the same teachers, when they are competing with one another for resources? Do we have any idea about how to stage the introduction of a successive focus on early reading, math and science? Strategies to get your faculty to do a better job with 1st grade reading may conflict with other things we are doing to help them do a better job at 2nd grade math instruction.

We need to think about how to develop schools into learning institutions that have their own internal development trajectories. We know how to do reform efforts that focus on one thing at a time, but we don’t have any models for doing multiple reforms simultaneously.

BUILDING INSTRUCTIONAL CAPACITY

Instruction as a Complex System of Social Interaction

David Cohen, who participated in one of the preconference workshops, described a conceptual model that clarifies some of the challenges in addressing this problem (Cohen et al., 2001). In Cohen’s view, improving instructional capacity in reading or mathematics or across many fields is not simply a matter of improving the curriculum or teacher preparation. Drawing on the work of Vygotsky (1978), Cohen views instruction as a function of the interaction between students and teachers. Viewed in this way, the social environment of the surrounding community is not simply an extraneous factor that can affect instruction at school. Instead, Cohen argued, children could be considered “delegates” from the outside world who bring with them to instruction all sorts of knowledge, beliefs, and values that may be more or less familiar to their teachers and to other

kids. Viewed in this way, the environment becomes active within instruction, as children enact it and teachers respond to it.

|

School improvement is a problem of knowledge use at many lev els. It is also a problem of creating organizations that respect and support knowledge use. . . . It is something that public educa tors have only begun in a few cases to apprehend as a real prob lem. David Cohen, Workshop Presenter |

Instructional capacity then, is not a quality of curricula. It is not an attribute of teachers, nor is it an attribute of students. Instructional capacity consists of their interactions. So, if one wants to improve instructional capacity and the learning that results from it, one must simultaneously address the many things that affect that interaction. In Cohen’s model, then, considering the quality of instruction apart from the qualities that characterize school-community relations is necessarily artificial and incomplete. Cohen identifies four factors that are essential to improving instructional capacity:

-

coordination of instruction,

-

use of resources,

-

mobilizing incentives for performance, and

-

managing the environment.

To improve instructional capacity, one has to think beyond how to get teachers more professional development, how to improve the curriculum, and how to make sure that students have adequate nutrition, eyeglasses, etc. All of these things are important, but it is entirely possible to address each of them singly and still have teachers unable to make use of these improvements to enhance student learning. Rather, the various elements that could contribute to improved instruction must be coordinated with each other around the goal of learning. As Cohen put it, “because instruction is interactive, there are almost infinite possibilities for discoordination between teachers and students about what they are doing.”

Linking School and Community in Education Reform

Many schools lack essential resources that could improve instruction. Cohen believes that many other schools, however, do not use what they

have. Resources are of no value if they are not used. For example, a well-designed curriculum unit or readily available computer resources do no good if the curriculum unit cannot be fit into the schedule, or if there is no strategy for integrating computer use into a comprehensive instructional plan. Incentives must be mobilized to support both students’ and teachers’ motivation to excel. Finally, the environment of the school, along with the various environmental influences of home and community, need to be managed in a manner that is conducive to student learning. Ideally, the environments of school, home, and community function to mobilize the incentives of students to learn and the incentives of teachers to teach effectively. The incentives affecting the behavior of all actors involved in the instructional process need to be aligned, necessary resources must be available and used, and all of this must come together in a coordinated way to enhance instructional capacity.

When the four factors that Cohen sees as central to improving instructional capacity are addressed in a comprehensive way, then one can plausibly expect education reforms to take root. The seeming intractability of many educational problems over the years gives evidence of the complexity of this task, underscoring the limitations of unidimensional and scattershot approaches to reform. As Cohen put it, scaling in reform programs is a very difficult task that must be accomplished before one can plausibly expect to be successful in scaling up. Supportive government policies, superior curricula, well-prepared teachers, and ample educational resources are helpful to this task. However, there is no escaping the fact that implementing program elements that effectively coordinate these components so as to enhance instructional capacity must occur one school and one community at a time—a point underscored later in the conference by Robert Slavin.

SUMMARY

This chapter and the conference presentations on which it is based have focused primarily on cognition and learning, early childhood development, and teaching young children to read. Conference presenters highlighted the implications of this research for enhancing the education of minority and disadvantaged students and the theme of achieving high educational standards for all. A common thread running through all of the presentations is that education reform should not be thought of as something that takes place solely in school—although both basic and applied research have demonstrated school-based reforms that are promising and certainly would contribute to improved student learning.

The personalization of learning—tying school-based learning into the relevant structures of students and their families—is particularly impor-

tant during early childhood. But, as emphasized by John Bransford, personalization is essential to learning for older children and adults as well, and it is especially important for minority and disadvantaged students. Personalization is a theme that cuts across all of the presentations discussed in this chapter.

There is much that educators can do to demonstrate the relevance of school-based lessons to minority and economically disadvantaged students in ways that can be both compelling and culturally sensitive. Yet, as argued by Edmund Gordon, the adverse effects of economic insecurity and the legacy of racial discrimination have had an enormous impact on the schooling of minority and low-income students.

How do race/ethnicity and social class affect student learning? What can schools do to mitigate their effects and ensure that all students, regardless of background, have an equal opportunity to learn? How close are schools to providing students with equal educational opportunities, when the educational outcomes of students vary so much by race/ ethnicity and class? These are among the issues examined in Chapter 4.