6

RESEARCH AREA 5

LAND USE

Research on transportation and the environment has only recently begun to explore in any significant depth the complex relationships among land development patterns, transportation investments, travel behavior, and consequent environmental impacts.1 Decision makers and practitioners have little knowledge about, for example, the role the built environment may be playing in causing Americans on a per capita basis to drive more and to transport goods farther each year, as has been the pattern for several decades. Transportation professionals need to know more about other factors, in addition to land use, that have contributed to today’s travel patterns and that interact with land use in sometimes subtle ways to influence travel choices. Decision makers and practitioners also know very little about the reverse—how driving habits and related factors affect land use and community life. In general, a better understanding is needed of the complex forces that shape land development and subsequent community form so

that decision makers and the public can evaluate alternative policy and investment strategies for the future.

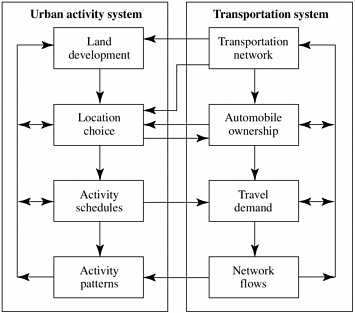

These are immensely challenging topics, in part because the causal relationships involved are two-way: land use has profound impacts on transportation, and transportation has profound influences on land use. Figure 6-1 illustrates this relationship. The land use–transportation relationship is depicted as two closed-loop systems that exert influence over each other. Simply put, the development of land for a particular use can generate new trips, thereby influencing demand and ultimately the need for new transportation facilities. Conversely, improvements to transportation systems have the ability to influence accessibility to existing activity centers, thereby improving land values and influencing location decisions and development patterns (Meyer and Miller 2000). Improving the knowledge base on these subjects is critical because—through the marketplace, public policy, or, more likely, a combination of the two—Americans will be making decisions about how to accommodate a likely 50 percent increase in population during the next half-century. These 140 million new residents will need mobility to access homes, schools, shops, workplaces, and recreation. Where and

FIGURE 6-1 Urban activity (including land development) and transportation systems interaction. (Source: Meyer and Miller 2000, Figure 3.7, p. 130.)

how this expected growth is distributed on the landscape is likely to have major implications for surface transportation, as well as for the landscape itself. The transportation community needs better information on ways to handle this growing population that better account for, respond to, and, where possible, avoid transportation-related environmental impacts.

SURFACE TRANSPORTATION AND LAND USE

Metropolitan areas in the United States expanded at rates from 2 to as many as 20 times faster than population growth during the second half of the 20th century (see Tables 6-1 and 6-2). Expansive land development has come to rural areas and small towns as well. According to the Department of Agriculture, in the 1990s Americans converted open space to developed land at a rate of 2.2 million acres per year or 251 acres per hour—a rate of conversion 50 percent greater than that of the 1980s2 (USDA 2000). The land most affected by the extent and pace of expansive development is that closest to existing cities and towns—the farms and open space that Americans often care most about. Development on the metropolitan fringe typically is low-density, scattered, and automobile-dependent. Some of the longest commutes in metropolitan regions are made by residents who live at the metropolitan edge. Not only are citizens and their leaders questioning the transportation impacts of such development, but they are also concerned about the effects of sprawling land development on ecosystems, farmland, scenic and historic resources, and Americans’ senses of place and community (see also Chapters 3 and 4). Citizens are concerned, too, about the economic and social consequences of prevailing development patterns, both for new communities with new fiscal burdens and for older communities left behind as investment and employment opportunities flow outward3 (Orfield 2002; Burchell et al.

TABLE 6-1

GROWTH IN POPULATION AND LAND CONSUMPTION, 1950-1990

|

Urbanized Area |

Population Growth, 1950–1990 (%) |

Developed Land Growth, 1950–1990 (%) |

Ratio of Area Growth to Population Growth |

|

Pittsburgh, Pa. |

9.50 |

206.30 |

21.72 |

|

Buffalo, N.Y. |

6.60 |

132.50 |

20.08 |

|

Milwaukee, Wis. |

47.90 |

402.00 |

8.39 |

|

Boston, Mass. |

24.30 |

158.30 |

6.51 |

|

Philadelphia, Pa. |

44.50 |

273.10 |

6.14 |

|

St. Louis, Mo. |

39.00 |

219.30 |

5.62 |

|

Cleveland, Ohio |

21.20 |

112.00 |

5.28 |

|

Cincinnati, Ohio |

49.10 |

250.70 |

5.11 |

|

Kansas City, Mo. |

82.70 |

411.40 |

4.97 |

|

Detroit, Mich. |

34.30 |

164.50 |

4.80 |

|

Baltimore, Md. |

62.70 |

290.10 |

4.63 |

|

New York, N.Y. |

30.50 |

136.80 |

4.49 |

|

Norfolk, Va. |

243.60 |

971.00 |

3.99 |

|

Chicago, Ill. |

38.00 |

123.90 |

3.26 |

|

Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn. |

110.70 |

360.20 |

3.25 |

|

Atlanta, Ga. |

325.40 |

972.60 |

2.99 |

|

Washington, D.C. |

161.30 |

430.90 |

2.67 |

|

34 metropolitan areas with population > 1 million |

92.40 |

245.20 |

2.65 |

|

Source: Meyer and Miller (2000). |

|||

TABLE 6-2

GROWTH IN POPULATION AND LAND CONSUMPTION, 1982–1996

|

Urbanized Area |

Population Growth, 1982–1996 (%) |

Developed Land Growth, 1982–1996 (%) |

Ratio of Area Growth to Population Growth |

|

Detroit, Mich. |

−1.1 |

19.6 |

– |

|

Rochester, N.Y. |

−3.1 |

15.5 |

– |

|

Buffalo–Niagara Falls, N.Y. |

0.0 |

52.0 |

– |

|

Pittsburgh, Pa. |

6.6 |

39.0 |

5.9 |

|

Harrisburg, Pa. |

14.5 |

72.0 |

5.0 |

|

Boston, Mass. |

5.6 |

26.9 |

4.8 |

|

Chicago, Ill.–Northwestern Ind. |

10.9 |

44.2 |

4.1 |

|

Cleveland, Ohio |

6.3 |

23.8 |

3.8 |

|

New York–Northeastern N.J. |

2.9 |

10.1 |

3.4 |

|

St. Louis, Mo.–Ill. |

9.2 |

30.8 |

3.3 |

|

Baltimore, Md. |

26.2 |

64.4 |

2.5 |

|

Nashville, Tenn. |

25.0 |

53.9 |

2.2 |

|

Tucson, Ariz. |

42.2 |

86.7 |

2.1 |

|

Las Vegas, Nev. |

138.9 |

243.8 |

1.8 |

|

Los Angeles, Calif |

23.4 |

22.7 |

1.0 |

|

Houston, Tex. |

27.5 |

9.8 |

0.4 |

|

Avg. of 70 U.S. metropolitan regions |

20.2 |

28.8 |

1.43 |

|

Source: Meyer and Miller (2000). Calculated on the basis of data from Texas Transportation Institute (1998). Developed land growth as represented by urbanized area in census data. |

|||

2002). The cumulative effect of individual development decisions is that development continues to occur in a dispersed pattern, for reasons that are not fully understood but that include a range of individual preferences, market forces, and public policies.

At the same time that metropolitan areas have been expanding, the amount of driving in personal cars and light trucks (mainly minivans, sport utility vehi-

cles, and pickup trucks) has also grown substantially. As with developed land area, driving has grown at a significantly faster rate than population. For the 5 years 1996 through 2000, driving grew at an average rate of more than 2 percent per year, ranging from a 3.1 percent increase in 1997 to no increase in 2000, a year of higher fuel prices and a dampened economy.4 Although the relationships of association and causation between the two trends are complex and only partly understood, their implications are significant for the future of community development, transportation planning, transportation system efficiency, and environmental quality.

Environmental Problems Associated with the Land Use–Transportation Connection

Understanding how metropolitan growth and travel trends are related—how land use and other factors, including national and local policies and investment decisions, influence travel behavior—will be fundamental to the choices American society must make as the country’s population and economy grow in the 21st century. What is apparent now is that, whatever the causes, the absolute and per capita growth in vehicle travel has been associated (either directly or indirectly) with the expansion of metropolitan areas and with a number of environmental problems.

Tailpipe Emissions

While improved emissions technology has resulted in cleaner air in many parts of the country, transportation in the United States still contributes some 450 million metric tons annually of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, to the atmosphere (see Chapter 2). This figure represents about 32 percent of total U.S. carbon emissions, and the amount is growing rapidly. Carbon emissions from transportation are increasing at a 20 percent faster rate than overall

emissions from all sources.5 In addition, as discussed in Chapter 2, cars and other highway vehicles constitute a continuing major source of air pollutants that are harmful to human health, including carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides, diesel soot, and a number of carcinogenic and toxic chemicals.6

A publication of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) summarizes the situation and suggests that the rising trend in emissions from transportation sources is due in substantial part to urban sprawl and changes in land use:

Despite considerable progress, the overall goal of clean and healthy air continues to elude much of the country. Unhealthy air pollution levels still plague virtually every major city in the United States. This is largely because development and urban sprawl have created new pollution sources and have contributed to a doubling of vehicle travel since 1970. (EPA 1994)

Government analysts are concerned that current trends in vehicle trips and miles driven, even with continuing incremental improvements in emission control systems, threaten to reverse recent national improvements in air quality by causing increases in total emissions of not just carbon dioxide, but also other pollutants (including sulfur dioxide and particulates) (EPA 2001a; EPA 2001b; FHWA n.d.; EPA 1993). Nitrogen oxide emissions are of particular concern. Despite improvements in the emission performance of individual vehicles, total nitrogen oxide emissions from highway vehicles rose

some 2.1 percent from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. Although there was some leveling in the latter part of the 1990s, Department of Transportation analysts predict that nitrogen oxide emissions from highway vehicles will grow between now and 2015 in metropolitan areas that experience continued traffic growth unless tighter vehicle controls than those currently scheduled are adopted (FHWA 1996b, 19; DOT 1995, 12).

Infrastructure-Related Impacts

Transportation decision makers have frequently responded to the increasing volume of automobile travel by building more roads. The mileage of public roads and streets in the United States grew steadily after 1900 to nearly 4 million miles in 1999 (BTS 2000, 6, Table 1-4). Nationwide, roads now occupy 11.1 million acres, an area equal in geographic size to the states of Maryland and Delaware combined. Parking lots are estimated to occupy an additional 1.2 to 1.9 million acres (EPA 2001a; EPA 2001b). Private infrastructure has grown as well: analysts report that in the 1990s more space was devoted to parking than people in typical new suburban workplaces, providing as much as 1,400 square feet of parking, usually in surface lots, for every 1,000 square feet of office space (Downs 1992). As discussed in Chapter 3, transportation-related pavement is a major source of runoff water pollution in many water-sheds.7 Highways also fragment wildlife habitats and significantly alter previously pristine areas. In addition, it is becoming increasingly clear that new highway capacity can itself induce additional travel and land development, which in turn can necessitate still more roadway space and other infrastructure, although the extent and workings of this dynamic are still largely to be determined, and more research is needed before any definitive conclusions can be drawn (Noland and Lem 2002).

Social and Economic Impacts

Although the focus of this report is on the environment, it bears mention that the impacts of traffic and land development go further. With growth in driving

has come increased congestion.8 Today 70 percent of peak-hour travel on urban Interstate highways occurs on congested roads operating at more than 80 percent of capacity. Researchers have estimated the annual cost to the American economy of lost productivity from congestion-related delays to be $78 billion in 1999. At current rates of population growth and urban expansion, public agencies lack sufficient fiscal resources to keep pace with congestion and Americans’ increasing propensity to travel by automobile through the construction of expensive new highway lanes, even if the provision of more roadway space were to constitute an adequate response.

Growth in traffic and land development has substantial impacts on communities in addition to congestion. As investment follows transportation facilities to the fringe of metropolitan regions, existing communities in central cities and traditional towns can suffer declining jobs and opportunities. This pattern can have serious consequences for populations left behind, including a disproportionate number of low-income neighborhoods (see Chapter 4).

Dispersed and low-density land development also requires increased expenditure of scarce economic resources for additional infrastructure beyond that related to transportation, such as schools, sidewalks, crosswalks, public safety, water, sewer, natural gas, electric power, telecommunications, and other utility lines. Some have estimated that the infrastructure needed to serve low-density development costs 9 to 12 percent more per capita than that required for more compact land use (Burchell et al. 2002). Moreover, service routes for mail and parcel delivery, police, and fire and ambulance units may become longer and less efficient.

CURRENT STATE OF KNOWLEDGE

Researchers have studied the causes of growth in automobile and truck travel and the relationships of that growth to urban and regional development patterns. However, most of the work has been conducted on a limited scale and scope; there has been little or no coordination of the research. Researchers have evaluated cases of local transportation and land development policies,

but have used such widely different variables and definitions that comparisons across studies are not always possible. A number of studies have examined correlations between travel and land development patterns, but have not controlled for such variables as household income, household size, automobile ownership, and age of household members, leaving the findings subject to interpretation. Research has also been limited by a lack of data or a lack of resources to assemble available data from local sources. Other than in a few regions, the subject has not been a major focus of government or other institutional activity.

Despite these shortcomings, it is generally accepted that travel is substantially affected by land use and urban development patterns; that federal, state, and local government policies significantly affect both travel and land use choices; and that current trends have significant adverse consequences for air and water pollution, emissions of greenhouse gases, natural ecosystems, and the American landscape (Giuliano 1995; Garrison and Deakin 1991). Questions remain concerning the magnitude of the effects, the relative contribution of transportation policies to travel and development choices, the role of current public policy in steering these choices and outcomes, and alternative policy instruments that might be considered. In many cases, the findings of current research suggest where future study should be directed.

Effects of Development Patterns on Travel Behavior

Much of the research undertaken to date has focused on the relationships between the density of residential neighborhoods and household travel behavior. Some of this research has been performed by environmental organizations, in cooperation with the federally chartered mortgage institution Fannie Mae and other federal agencies, to investigate the impact of neighborhood characteristics on transportation spending patterns.9 Related research on household density, neighborhood characteristics, and travel behavior has been scattered among a number of institutions. For example, such research has been conducted in the private sector at the Urban Land Institute and at a number of academic institutions, and summarized in presentations at meetings of the Transportation Research Board.10 International research on the subject includes

that sponsored by the World Bank, as well as that conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the European Council of Ministers of Transport.11

The overall body of work on density and travel, notwithstanding differences in methodologies and variations in specific results, is generally consistent in its findings: as population and employment density decline, as occurs with expansive land development, travel distances lengthen, vehicle trips and usage increase, and transit usage and walking decline. Indeed, these associations have been demonstrated in research dating as far back as 1963 (Handy 1997).

An extensive 1998 review of the literature on the costs of sprawling land development performed for the Transit Cooperative Research Program found support for all of these conclusions. With respect to growing vehicle-miles traveled (VMT), the review led to the following conclusion:

Three factors have contributed about equally to the growth in VMT— changing demographics, growing dependence on the automobile, and longer travel distances. Thus, sprawl, which creates the longer travel distances and increased dependence on the automobile, is a major source of increased vehicle use. (Burchell et al. 1998)

The review also revealed support in the literature for the proposition that sprawling land use reduces the cost-efficiency and effectiveness of transit service as compared with more compact development, and causes households to spend higher proportions of their income for personal transportation. Moreover, travel in sprawling areas generates higher social costs. Findings on the effects of sprawl on total travel times were mixed.

Researchers have investigated a number of other factors in addition to land use density that contribute to travel patterns. One important category of such factors encompasses the effects of other neighborhood characteristics, such as the extent to which jobs, housing, and other activities are mixed or separated from each other in development parcels; the presence or absence of pedestrian amenities; and proximity to central business districts and transit stations (see, for example, Frank and Pivo 1994; Cervero 1996; Ewing and Cervero 2001; Dunphy and Fisher 1996). Most of the studies addressing these factors

are small, and there are wide variations among the results. Nevertheless, the available evidence indicates that these factors also are relevant to the number of driving trips made and the distances driven.

Other Factors Relevant to Land Use and Travel

In addition to research on the effects of development patterns on travel, several scattered lines of inquiry are addressing other factors that may be relevant to land use, travel, or both. One such factor is government policies that may have the ancillary effect of causing or contributing to low-density development patterns. These policies include, for example, zoning regulations; state and federal tax policies; subsidies for sewage treatment facilities; and even implementation of state or federal regulatory statutes, such as the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. There is little existing research on these subjects. The same can be said for research on how highways and public transit facilities affect development patterns and communities, although the issue has been examined both in histories (e.g., Warner 1962; Jackson 1985) and in a long but sparse series of empirical case analyses (e.g., for transit, Spengler 1930; Boyce et al. 1972; Gannon and Dear 1972; Webber 1976, Knight and Trygg 1977; Landis and Loutzenheiser 1995; Weinberger 2001; for highways, U.S. Congress 1961; Payne-Maxie and Blayney-Dyett 1980; Forkenbrock et al. 1990; Boarnet 1995; Hansen et al. 1993).

Research is even more widely scattered and piecemeal on other potentially relevant phenomena, such as the effect on travel of such factors and trends as changing demographic characteristics, shifts in consumer and household opportunities and preferences, changes in the organization and location of workplaces, and shifts in shopping habits (Kitamura 1988; Kitamura et al. 1994; Redmond and Mokhtarian 2001; Ferrell and Deakin 2001). Knowing more about such factors is essential to understanding the true impacts of land use.

Sparse research has also been undertaken to test a number of claims about the positive transportation-related impacts of expansive land use. The 1998 literature review noted above (Burchell et al. 1998) and a more recent study on sprawl by the same authors (Burchell et al. 2002) cite a number of these claims, including shorter commuting times (if not distances), reduced congestion, lower governmental costs (because transit is claimed to require greater subsidy than driving), and travel efficiency. These reviews reveal that the work to date on these claims has failed to produce a consensus. Yet these claimed benefits are highly relevant to the attractiveness and likely success of attempts

to affect travel behavior through alternative forms of land development, and need to be understood.

Ultimately, a critical goal of scientific inquiry into the relationships between land use and transportation must be improving the ability of decision makers, practitioners, and the public to evaluate the likely effects of different policy and investment choices on travel behavior and communities. New, technologically advanced tools, such as geographic information systems and other forms of visual imaging, are becoming available to assist in these efforts. In some applications, technology for forecasting land use patterns and integrating land use and transportation models is improving as well. The substantial LUTRAQ (land use, transportation, and air quality) effort undertaken in Portland, Oregon, in the 1990s and the ongoing SMARTRAQ (Strategies for Metropolitan Atlanta’s Regional Transportation and Air Quality) research initiative in Atlanta illustrate how these tools can be applied (1000 Friends of Oregon 1997). The need to strengthen existing tools and models for assessing land use and transportation has been documented at recent conferences of modeling experts (Shunk 1995).

Lack of Research Coordination

One of the most challenging obstacles to advancing understanding of the relationships between transportation and land use is that there is no central repository, coordinating body, or effective cataloging operation to which one can turn to locate salient data and evidence and assess relevant studies.

Looking only at the federal government, for example, no agency or institution is in charge of tracking and assembling land use–transportation information, to say nothing of communicating such information to potential users and the public. Instead, there are numerous independently conceived and managed studies scattered among separate institutions, including the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Highway Administration, the Federal Transit Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Energy, Fannie Mae, and others. These institutions rarely coordinate closely with each other; in fact, they frequently lack sufficient internal coordination. This fragmentation is also apparent in the scattered undertakings among the 50 states, various real estate development interests, environmental organizations, transportation service providers, universities and other research institutions, trade associations, and private corporations.

Benefits of Increased and More Focused Research

A better understanding of the interactions among land use, public and private transportation infrastructure, and travel behavior could have profound economic and environmental benefits by helping states, localities, and their federal partners allocate both public and private resources more wisely. Better-informed decisions about the consequences of alternative development and transportation investment scenarios could help reduce public expenditures and private costs and generate potentially large reductions in air emissions and other pollution from transportation, while avoiding unnecessary impacts on the landscape.

Although many of the problems associated with transportation and development patterns (e.g., increasing congestion, loss of open space due to urban sprawl) are evident to most Americans, the solutions are far less obvious. A commitment to better, expanded, and more systematic research on these issues could aid in finding ways to meet the access and mobility needs of America’s citizens while reversing, or at least limiting the growth of, travel and development patterns that have significant environmental impacts.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 5-1.

Expand and focus research on the impacts of development patterns and characteristics on travel behavior.

Existing research indicates that neighborhood density, mix of uses, pedestrian amenities, and related characteristics may have significant impacts on travel behavior. The research suggests that encouraging different development patterns could play a significant role in helping to reduce infrastructure needs and limit growth in the number of vehicle trips made and miles driven, thereby playing a role in reducing environmental impacts as well. If the land use and mobility needs of a growing population and economy are to be met, it is critical that this research be intensified and expanded. Examples of useful future research in this area are presented below.

Example: Expanded geographic scope. To date, study of the influence of neighborhood form on travel has been geographically limited. For example, the research on travel expenditures and urban form being conducted by nonprofit environmental organizations in cooperation with Fannie Mae is currently

limited to three major U.S. cities; other research has been even more limited, to specific neighborhoods or developments. Additional studies should extend this type of inquiry to other cities, including smaller ones, and to nonmetropolitan areas as well. The research should be coordinated so that comparisons can be made across cases. Comparison of the results for different communities could both enhance understanding of the dynamics of the land use–transportation relationship and suggest different approaches for encouraging greater travel efficiency that may be appropriate to particular areas.

In addition, Americans drive cars and trucks nearly twice as much as do Europeans per capita, and more than twice as much as do the Japanese12 (FHWA 1998, Section VI). Neighborhood density and related factors could perhaps explain this difference, but so might fuel or automobile prices, or differences in policy or culture. It would be useful to expand and refine current knowledge of the extent to which the associations with neighborhood characteristics found in American cities also apply in European and Asian cities—for example, whether differences in household income levels have similar impacts in different countries. If the general tendencies are the same throughout the world, the findings might assist in other lines of inquiry, such as the extent to which gasoline and automobile price differences affect travel behavior.

Example: Refinements in methodology. Research is needed to improve on the current methodology used to study the impacts of development patterns on travel behavior. For example, studies of urban design and its relation to travel behavior have typically relied on available data that may be too aggregate to capture all relevant effects. Future research might assess more precise characteristics of neighborhoods and locations, as well as various aspects of driving, walking, use of public transit, and other transportation behavior. The relative significance of other variables known to affect travel behavior, such as household size and income, could be tested more completely as well. An additional important line of inquiry is better understanding of the shape of the curve of the relationship between neighborhood density and driving: At what points of increased density do we reap the most benefit in terms of reduced driving?

Also needed is a better understanding of causality rather than mere correlation between neighborhood characteristics and travel. Given that a host of factors affect travel decisions and behavior, to what extent can trends and differences among locations be properly attributed to neighborhood characteristics instead of, for example, differences in income or household demographics? For instance, research shows that denser neighborhoods are associated with less travel, but how much of that effect might be explained by lower incomes, lower automobile ownership levels, and smaller household sizes that are often found in denser neighborhoods? Also, how much does travel behavior reflect urban form and travel opportunities versus personal and household characteristics? How important are transportation characteristics in housing location choices? Do people’s preferences for driving, taking transit, walking, and so on remain largely the same regardless of their location and the options offered? Or do those who move from more compact to more dispersed areas end up driving more and owning more cars? If behavior changes, how long does it take for the adjustment to occur? Are the results the same if the direction is reversed; that is, as people move from dispersed areas to compact neighborhoods, do they immediately begin driving less?

Finally, although it is likely that future research will confirm and refine the current understanding that development patterns play a significant role in influencing how much Americans travel and by what means, it is probable that other factors are significant and help explain rising rates of vehicle use. These factors might include, for instance, economic growth, rising personal incomes, new living options made possible by communications technology, entry of multiple household members into the workforce, and continued relatively low fuel prices, among others. To understand the true influence of land development patterns on travel behavior, it will be necessary to identify and assess the impact of these other factors as well (see also Chapter 7).

Example: Study of impacts on public transit. Another important linkage among land use, urban design, and travel behavior is the relationship between land use and public transit usage. Although transit still represents a small portion of total trips made nationwide, it represents a major and growing share in many places (APTA 2001; STPP 2001). Indeed, recent years have seen striking increases that reverse decades of declining ridership, and many public transit systems are now struggling to keep up with demand. One special focus of research on the relationship of neighborhood and location characteristics to travel behavior should be the impacts on transit usage, along with other factors affecting transit ridership, such as the comfort, safety, and

convenience of transit systems. Transportation planners and decision makers need to identify those combinations of factors most conducive to transit usage.

Example: Commercial locations and concerns. Much of the quantitative work to date relates to differences in travel behavior associated with various characteristics of residential locations—the typical origins of trips. Intuitively, however, it appears plausible that such characteristics as density, transit access, and pedestrian amenities could make a difference on the destination side as well. Indeed, the impacts might vary with particular types of commercial locations, such as workplaces, shopping areas, and service providers. Future research could explore these potential influences.

Some intriguing corollary questions concerning commercial locations also need to be explored more fully than in the past. The most recent comprehensive study of the impact of commercial development on travel is a Transportation Research Board study on travel characteristics of large-scale suburban activity centers (Hooper 1989). There is a need to update this study. For example, do suburban campus-style offices generate more or less travel than more compact or centralized alternatives, and is there any difference in travel time? Do regional malls and other suburban shopping centers generate different patterns of travel from those associated with traditional downtown areas? Does the concentration of jobs in a single location (a downtown) correlate with reduced or increased travel and travel times, and if so, to what extent? To what degree are differences in the distribution of high-paid versus low-paid (or professional versus industrial) jobs responsible for these effects? If a region has multiple centers or one center with subcenters, does this lead to more or less efficiency than having one large center? How much does the provision of parking, either paid or free, affect these results? What is the price elasticity connecting parking fees with the propensity to drive to work?

Moreover, nearly all of the existing research on these subjects is related exclusively to personal transportation. But one might hypothesize that areas with certain density and proximity characteristics are associated with reductions in trips and mileage for package delivery and other freight transportation as well, because the distances from retailer to distributor and from distributor to final recipient, for example, are smaller. An alternative hypothesis would be that freight transportation has a very different set of controlling variables from personal transportation and does not vary with urban design characteristics. These and related hypotheses should be tested.

Recommendation 5-2.

Continue and expand research on the impacts of transportation facilities.

Another important category of research encompasses the impacts of highway, transit, walking, and bicycling facilities on travel behavior, as well as on land use and the community.

Example: Transportation facilities and travel behavior. The body of evidence from the United States and elsewhere supports the notion of “induced demand”: that the demand curve for travel is like that for other goods and services and that, at least under some conditions, the construction or expansion of highway lane capacity will lead to more driving, not just make a preexisting amount of driving more efficient by relieving traffic congestion (Hansen et al. 1993; Cervero 1991; Boarnet 1995). Knowing the extent to which this supposition is true can help in making a more accurate determination of the long-range efficiency of transportation investments (see also Chapter 7). Moreover, while a helpful body of international research on the subject is available, it has not been applied extensively in American transportation planning. Thus there is also a need for better linkages between research on this subject in other countries and the United States.

Transportation professionals and decision makers need to have a better understanding of a range of factors relevant to behavioral responses to added capacity (induced travel), as well as to congestion. What conditions must be present for induced travel to occur? What role is played by land development induced or facilitated by highway construction? To what extent is induced traffic a cause of increasing regional travel volume? And given that added lane capacity may also produce at least short-term benefits, how does induced traffic affect the cost–benefit analysis of highways in particular situations? As metropolitan highway networks become more congested, it is also important to understand better how people and businesses adapt over time. Do they move farther out, relocate to more transit-accessible locations, move to less congested communities, or otherwise internalize the added costs of congestion?

Such research should not be limited to the impacts of highways. What happens when system providers add public transit access or capacity? What conditions must be present for the level of transit demand to be changed by facilities and investments? To what extent do transit facilities affect regional rates of driving? What effect do additional bicycle and pedestrian facilities have on transportation behavior, including rates of driving?

Example: Transportation facilities and land use, development, and community. Decision makers, practitioners, and the public need to know more about how transportation facilities affect land development, not just how development affects transportation. For example, it is evident from observation that the opening of new freeways is often followed by the construction of commercial facilities near exits. Is it reasonable to hypothesize that highway construction induces expansive land development? If so, can the development impacts be predicted? What is the geographic zone of influence of roadways and intersections in affecting development? How do these factors interact with changes in land prices due to improved access to influence development? To what extent, if any, does induced development play a role in the amount of and changes in overall regional vehicle use? (See Meyer and Miller 2000; Forkenbrock et al. 2001.)

There is also inadequate research on the influence of public transit facilities, especially fixed-rail transit construction, on property development near stations. Most of the research done on this subject examines residential property; only a few studies have addressed commercial property as well (Weinberger 2001). In addition, most of the available research has taken a very short-term perspective; more research concerning effects over a 25- or 50-year time horizon would be helpful. Research is also needed to examine the overall impacts (beyond those related to transportation per se) of transit stations and facilities on communities, and how those impacts vary with different types of communities and transit-facility designs.

Another important category of inquiry is the effects of transportation facilities on the social environment of communities as places to live, work, and play (see Chapters 4 and 7). What effects do highways have when they bisect existing communities and when they detour traffic around communities? Moreover, just as some communities are beginning to dismantle unpopular public housing projects, some are deciding not to repair or replace freeways, as was the case following the last major San Francisco earthquakes. How has the decommissioning of highways affected surrounding communities and travel behavior?

Roadway design has also become an important topic in many communities. Efforts are under way to reconsider design standards for major roads; these efforts include federal and state initiatives to develop context-sensitive designs. However, the concern that standard designs are often not sufficiently sensitive to impacts on place and community extends across the entire range of facilities, including regional and local arterials, collectors, and residential streets. Research should address the impacts (including but not limited to land use) of various design types on different kinds of rural areas, suburban communities, and urban

neighborhoods. Can an adequate template for context-sensitive design be developed? What are the impacts of alternative street designs on the affected neighborhoods, districts, and corridors and their inhabitants, and on transportation system performance? What effects do different forms of highway access management have on communities, development patterns, and related travel?

Finally, many municipalities have begun to implement measures designed to further community cohesion and safety, as well as to encourage walking and bicycling. Examples include traffic-calming measures, enhanced pedestrian crossings, shaded sidewalks, and dedicated bicycle lanes, among others. The transportation community needs to learn more about the effects of these measures on both travel patterns and affected neighborhoods and communities.

Example: Agency evaluation of impacts. The National Environmental Policy Act and many state laws require that the environmental impacts of major actions, including significant new transportation facilities, be evaluated prior to implementation. It is important that decision makers and other reviewers of impact statements understand not just the immediate impacts of a proposed facility (e.g., the loss of a particular wetland supplanted by a new roadway), but also the secondary and cumulative impacts, including the likely effects of the facility on travel behavior and land development. Research is needed to address emerging knowledge on these subjects and provide information and understanding that can serve as a basis for best practices.

Recommendation 5-3.

Conduct and expand research on the causes and benefits of current development patterns.

Evidence suggests that expansive land development and so-called “leapfrog” development that skips over undeveloped land are associated with increased motor vehicle use per capita. Such development patterns also cause or are associated with a wide range of additional environmental and social impacts (Burchell et al. 2002). In opinion polls, Americans register increasing concern about these impacts, as well as growing interest in and preference for alternatives.13 But there is little question that, despite the problems associated with low-density development and citizens’ expressed concerns about concomitant impacts, such development remains the dominant pattern of land use in the

United States. Thus there is an apparent dissonance between what people say they would like to experience with respect to community and their actual behavior. Given the emerging national interest in smart growth and other alternatives to sprawling development, researchers need to identify and understand the factors that contribute to dispersed growth patterns so these factors can be addressed to the extent possible. Research in this area might focus on two important categories of forces driving sprawl, as described below.

Example: Personal benefits and preferences associated with housing and business location. It has long been held, largely on the basis of anecdotal evidence, that residents and businesses have been choosing outer-suburban locations to escape problems that plague central cities, and now inner suburbs as well. These problems include a real or perceived greater risk of crime; unaffordable housing; expensive land prices; and, especially for families, inferior public school systems. There are also those who contend, with some empirical justification, that racism has caused white flight to the suburbs.14 In addition, residents and businesses are increasingly choosing outer-suburban locations simply to be closer to each other or to find a quieter environment (Burchell et al. 1998). Dispersed development patterns may also be caused or influenced by Americans’ patterns of time management, which are shifting because of emerging technology (see Chapter 5).

As noted earlier, some perceived benefits of suburban sprawl, such as shorter commuting times and reduced traffic congestion, are related directly to transportation. Others relate to the environment, such as the larger yards and personal open space available in some outlying developments, as well as real or perceived greater access to public and private open space beyond the metropolitan edge or on land passed over by leapfrog development. In many cases, residents who perceive their local environment to be threatened by any new development, regardless of how well designed, resist changing an expansively developed community to one that is more supportive of transportation efficiency. At the same time, higher inner-city housing values and the rapid sale of new residential offerings in more urban locations, as well as in more compactly designed new suburban developments, suggest that demand for urban and denser suburban locations remains high.

Government officials and other interested parties need to understand the extent to which these and other consumer preferences drive location decisions

and which of these factors are most important. Developers and land use planners need to learn whether the attributes preferred by residents and businesses can be provided in communities and developments with different urban designs. For businesses, it is especially important that the convenience of access to various markets (workers, clients, users) be among the attributes studied.

Example: Public policy influences. A range of public policies appears to be important in influencing the shape and location of development. Examples include zoning and building codes that once made sense (such as those mandating large lot sizes or separation of residential and commercial uses), but that now often limit market-based decisions that could support the building of developments more conducive to walking and transit. A related topic is local governments’ frequently apparent preference for revenue-generating commercial developments and opposition to developments (particularly those with affordable housing) that require expensive government services, such as schools. Some observers have also expressed concern that interpretation of certain federal regulatory statutes, such as the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, may unintentionally contribute to dispersed development. Research is needed to investigate such claims.

A number of related questions need to be explored. For example, how do federal, state, and local tax policies, including special policies for particular developments, influence development decisions? To what extent do competitive tactics among different municipalities—for instance, offering subsidies, free infrastructure, and tax breaks to attract businesses—lead to some forms of development? To what extent do state and federal assistance programs for infrastructure, such as roads, schools, and water treatment, provide incentives for choosing dispersed rather than central or compact suburban locations? And what impact does the location of government facilities themselves, such as courthouses, post offices, and agency offices, have on local development patterns? Participants in location decisions need to learn more about which of these factors have been most influential in shaping the built landscape and how shifts in policy are most likely to produce different results.

Recommendation 5-4.

Assess and compare alternative transportation and land use strategies.

Closely related to causes of vehicle use and expansive land development are questions concerning how different transportation and land use strategies will most likely affect travel patterns (see Chapter 7). Many communities are

interested, for example, in obviating the high cost of building new highway capacity to free resources for maintenance of the existing system; many are also struggling to overcome increasing traffic congestion. In addition, finding effective methods for educating the public on the connections between land use and transportation is critical.

Example: Effectiveness of strategies. Because of the complexity, difficulty, and cost of modeling long-run changes in land use and travel behavior given different transportation investment scenarios, many metropolitan areas do not use very sophisticated techniques to analyze land use as part of the transportation planning process by incorporating the interaction over time among new facilities, subsequent land development patterns, and altered travel behavior. A striking exception is the LUTRAQ study in Portland, Oregon, which involved extensive evaluation over several years. A somewhat more developed body of international research has also been undertaken, although its applicability to the U.S. context is uncertain (see, e.g., Mackett 1985 and Wegener 1987).

Efforts such as LUTRAQ and SMARTRAQ that involve simultaneously evaluating land use and transportation scenarios need to be applied elsewhere and made simpler for communities with limited resources. In addition, a broad range of research should be undertaken at multiple sites across the United States to determine what effects different strategies have on travel behavior and which approaches are most effective in reducing pollution and other environmental impacts. Available options might include the following: transit-oriented development and other land use strategies, such as those discussed earlier; rideshare strategies, including increased use of paratransit services; road pricing; improvements to public transit systems; park-and-ride lots or structures at transit stations; and other market-oriented or regulatory techniques. All of these options should be explored.

Research should also address the effectiveness of, and problems associated with, policy measures being developed and applied across the country to shape land development in a more environmentally benign manner. These measures include, for example, urban growth boundaries (such as those pioneered in Oregon), limits on infrastructure spending in locations less desirable for development (such as those being applied in Maryland), land conservation measures (such as conservation easements and programs for the purchase of development rights), financial incentives to homebuyers in smart-growth locations (such as the location-efficient mortgage), direct acquisition of lands that should be protected from development, tax policies, the imposition of local impact fees and exactions, and special zoning in areas targeted for development.

American communities are increasingly employing variations on and combinations of these growth-management techniques, all of which have potentially significant implications for transportation investment needs and travel choices. A portion of the research agenda should be directed to studying the impacts and effectiveness of all the available strategies, and identifying those aspects and combinations that are most effective, as well as the social and economic conditions and institutional and policy frameworks most supportive of particular approaches. Studies might also be undertaken to compare and improve our understanding of the current differences in land use and travel behavior among communities with widely divergent characteristics, such as Portland, Houston, Phoenix, and Boston. In addition to investigation at the community level, analysts should compare the likely effects of alternative policy and investment scenarios at the state and federal levels.

Example: Development and refinement of models for assessing strategies. In investigating the above questions, researchers will frequently need to develop better methodologies that are sensitive enough to predict the likely outcomes of alternative policy choices. Such new models might encompass many variations. One example is the development of a better method for assessing the economic attractiveness of alternative scenarios comprising different combinations of transportation investment and management decisions and land use planning and development patterns. Transportation is one of the largest categories of public expenditure, yet there is not a valid and accepted methodology for comparing, within a given geographic sector of a metropolitan region, the economics of roadway investments versus different sorts of transit expansions and land use strategies in a way that accounts correctly for the likely effects of development patterns on travel behavior.

The performance of integrated land use–transportation models also should be examined to determine what refinements to the models are needed. For example, forecasts of the LUTRAQ model could be evaluated and their prediction accuracy assessed. With each passing year, more data become available to illuminate how accurate that model has been in predicting travel behavior and what refinements might be appropriate. Other applications of integrated transportation land use models might similarly be evaluated.

Transportation professionals are hampered by the fact that current models used to predict travel behavior do not deal well, if at all, with walking and bicycling and with short trips in general. Since many land use and community design strategies are aimed at encouraging walking and cycling and reducing trip lengths, this is a major shortcoming. Models should be developed that are

capable of accurately evaluating the potential substitution of walking trips for motorized travel under different land use scenarios. Some current research suggests that the effects of transit facilities and walking on travel patterns may be more extensive and subtler than is allowed for by current models.

Using existing research as a starting point and developing additional methodologies, researchers and planners might attempt to create a template that could be used by a region to satisfy its accessibility and mobility needs at minimum cost. The objective of such a template would be to determine optimum investments in highway capacity and transit expansion for any given land use pattern, while taking into account economic incentives for development that is more compact. A tool that would aid in least-cost planning could have immense practical benefits in supporting what are now mainly informal and underinformed evaluative processes. (Additional issues with respect to planning methods are discussed in Chapter 7.)

Example: Models for regional cooperation. Changes in federal transportation law—the most important of these being the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act and its successor, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century—have made a difference in encouraging states, municipalities, and metropolitan regions to work together in planning a region’s major transportation investments (at least those that receive federal funds). This change is important because regional economies and travel patterns predominate in today’s highly mobile and interconnected world. Residents and businesses seldom remain within their own jurisdictional borders as they go about their daily business. Yet many metropolitan regions have yet to achieve the level of cooperation anticipated by Congress in federal transportation legislation. For example, concerns are frequently raised about the adequacy of representation of different jurisdictions and constituencies within metropolitan planning organizations.

One of the most significant challenges to be met is the coordination of transportation and land use planning (see also Chapter 7). Ideally, it is desirable to plan the two together because of the extent to which they influence each other. While some incremental progress has been made in regional transportation thinking, minimal progress has been achieved with regard to regional decision making for land use, which remains the near-exclusive domain of the smallest units of government in most locations. The difficulties posed by this dynamic can be immense given the sheer number of government units that can be involved in a given region. Metropolitan Chicago, for example, has been estimated (though the reported estimates vary) to comprise some 267 municipalities and counties

and some 1,250 “governments” of one sort or another, including various school and service districts and regional authorities. All of these entities can have impacts on land use patterns and, by extension, on the transportation system. Such jurisdictional fragmentation can make regional coordination of transportation and land use virtually impossible.

Portland (Oregon), Minneapolis–St. Paul, and Atlanta are among the metropolitan regions that are attempting to overcome this challenge with new regional institutions. Other arrangements are being developed in various locales around the country, with wide variation among strategies and methods. As regions gain experience with coordination mechanisms, it is important that these undertakings be monitored and assessed, and that further study be undertaken to ascertain which mechanisms hold the most promise in furthering the ability of regions to consider land use and transportation together rather than separately. Both evaluation research and exploration of new forms of cooperative planning would be important.

Recommendation 5-5.

Translate research findings into accessible tools for practitioners and citizens.

As noted earlier in this chapter, research on the interactions between land development patterns and transportation has been piecemeal and scattered with respect to both substance and geography. The field comprises a rather bewildering array of disconnected literature and undertakings that even experts find difficult to identify, assemble, and apply. And nowhere is the bewilderment felt more acutely than at the state and local levels, where transportation planners and engineers, along with elected officials and their citizen constituents, must make sense of policy options. Practitioners and citizens need new tools that can make this body of evolving information more accessible and easy to use. Such accessibility can take many forms—from the development of so-called “sketch” models that can reveal quickly and broadly the likely impacts of alternative development scenarios, to sophisticated new visual applications using geographic information system technology, to traditional best-practices manuals (see Chapter 7). Development of such tools is an essential component of any meaningful research agenda on transportation and land use.

In making this complex body of research more accessible, some attention needs to be paid to the dissemination of data on overall land development and transportation trends and patterns. Currently, a lack of standards and uniform

practices in collecting and reporting these data limits their availability and usefulness. In fact, more research should be conducted on means of assessing and improving upon current methods for measuring land use characteristics and patterns. Special emphasis should be placed on techniques that use computer imagery and other visual media.

At the same time, there is a need to improve education and training among transportation professionals so that state departments of transportation and other public agencies will have enhanced expertise on these often rapidly developing issues. There is a particular need for urban planners and other land management professionals to help coordinate transportation and land use planning at the state level.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

APTA American Public Transportation Association

BTS Bureau of Transportation Statistics

DOT U.S. Department of Transportation

EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

NTI National Transit Institute

STPP Surface Transportation Policy Project

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

American Farmland Trust. 2001. Protecting Our Most Valuable Resources: The Results of a National Opinion Poll, 2001. Washington, D.C.

American Planning Association. 2000. The Millennium Planning Survey: A National Poll of American Voters’ Views on Land Use.

APTA. 2001. Public Transportation Ridership Statistics: Third Quarter—2001. Washington, D.C.

Boarnet, M. G. 1995. New Highways and Economic Growth: Rethinking the Link. Access: Research at the University of California Transportation Center, No. 7, Fall, pp. 11–15.

Boyce, D. E., B. Allen, R. R. Mudge, P. B. Slater, and A. M. Isserman. 1972. Impact of Rapid Transit on Suburban Property Values and Land Development. PB 220 693. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

Brookings Institution. 2000. Moving Beyond Sprawl: The Challenge for Metropolitan Atlanta. Washington, D.C.

BTS. 2000. National Transportation Statistics 2000. U.S. Department of Transportation.

Burchell, R. W., N. A. Shad, D. Listokin, H. Phillips, A. Downs, S. Seskin, J. S. Davis, T. Moore, D. Helton, and M. Gall. 1998. TCRP Report 39: The Costs of Sprawl— Revisited. TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Burchell, R. W., G. Lowenstein, W. R. Dolphin, C. C. Galley, A. Downs, S. Seskin, K. G. Still, and T. Moore. 2002. TCRP Report 74: Costs of Sprawl—2000. TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Cervero, R. 1991. Land Uses and Travel at Suburban Activity Centers. Transportation Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 4.

Cervero, R. 1996. Jobs-Housing Balance Revisited: Trends and Impacts in the San Francisco Area. Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 62, No. 4, Autumn, pp. 492–511.

DOT. 1995. Our Nation’s Travel: 1995 NPTS Early Results Report.

Downs, A. 1992. Stuck in Traffic: Coping with Peak-Hour Traffic Congestion. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Dunphy, R. T., and K. Fisher. 1996. Transportation, Congestion, and Density: New Insights. In Transportation Research Record 1552, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., pp. 89–96.

EPA. 1993. Automobiles and Ozone. Fact Sheet OMS-4. Office of Mobile Sources.

EPA. 1994. Motor Vehicles and the 1990 Clean Air Act. Fact Sheet OMS-11. Office of Mobile Sources.

EPA. 2001a. EPA Guidance: Improving Air Quality Through Land Use Activities. EPA 420-R-01-001.

EPA. 2001b. Our Built and Natural Environments: A Technical Review of the Interactions Between Land Use, Transportation and Environmental Quality. EPA 231-R-01-002.

Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2001. Travel and the Built Environment: A Synthesis. In Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 1780, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., pp. 87–114.

Ferrell, C., and E. Deakin. 2001. Changing California Lifestyles and Consequences for Mobility. Working Paper 545. University of California Transportation Center, Fall.

FHWA. 1996a. Summary of National and Regional Travel Trends: 1970–1995. U.S. Department of Transportation.

FHWA. 1996b. Transportation Air Quality: Selected Facts and Figures. FHWA-PD-96-006. U.S. Department of Transportation

FHWA. 1998. Highway Statistics 1998. U.S. Department of Transportation.

FHWA. n.d. VMT Growth and Improved Air Quality: How Long Can Progress Continue? www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/vmt_grwt.htm.

Frank, L. D., and G. Pivo. 1994. Impacts of Mixed Use and Density on Utilization of Three Modes of Travel: Single-Occupant Vehicle, Transit, Walking. In Transportation Research Record 1466, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., pp. 44–52.

Forkenbrock, D. J., T. F. Pogue, N. S. J. Foster, and D. J. Finnegan. 1990. Road Investment to Foster Local Economic Development. Public Policy Center, University of Iowa, May.

Forkenbrock, D., S. Mathur, and L. Schweitzer. 2001. Transportation Investment Policy and Urban Land Use Patterns. Public Policy Center, University of Iowa.

Gannon, C., and M. Dear. 1972. The Impact of Rail Rapid Transit Systems on Commercial Office Development: The Case of the Lindenwold Line. PB 212 906. Urban Mass Transportation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation.

Garrison, W. L., and E. Deakin. 1991. Land Use. In Public Transportation (G. Gray and L. Hoel, eds.), Prentice-Hall, New York.

Giuliano, G. 1995. Transportation and Land Use. In The Geography of Urban Transportation, 2d ed. (S. Hanson, ed.), Guilford Press, New York.

Handy, S. 1997. How Land Use Patterns Affect Travel Patterns: A Bibliography. Council of Planning Librarians.

Hansen, M., D. Gillen, A. Dobbins, Y. Huang, and M. Puvathingal. 1993. The Air Quality Impacts of Urban Highway Capacity Expansion: Traffic Generation and Land Use Change. UCB-ITS-RR-93-5. Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Berkeley.

Holtzclaw, J. 1994. Using Residential Patterns and Transit to Decrease Automobile Dependence and Costs. Natural Resources Defense Council, San Francisco, Calif.

Holtzclaw, J., R. Clear, H. Dittmar, D. Goldstein, and P. Haas. 2002. Location Efficiency: Neighborhood and Socioeconomic Characteristics Determine Auto Ownership and Use—Studies in Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Transportation Planning and Technology, Jan.

Hooper, K. G. 1989. NCHRP Report 323: Travel Characteristics at Large-Scale Suburban Activity Centers. TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Jackson, K. T. 1985. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, New York.

Janes, M. 1999. States, Local Policymakers Stress Livability Issues. AIArchitect, Sept.

Kitamura, R. 1988. Life-Style and Travel Demand. In Special Report 220: A Look Ahead: Year 2020: Proceedings of the Conference on Long-Range Trends and Requirements for the Nation’s Highway and Public Transit Systems, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., pp. 149–189.

Kitamura, R., P. L. Mokhtarian, and L. Laidet. 1994. A Micro-Analysis of Land Use and Travel in Five Neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area. Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Davis.

Knight, R. L., and L. L. Trygg. 1977. Land Use Impacts of Rapid Transit: Implications of Recent Experience. U.S. Department of Transportation.

Kuzmyak, J. R., R. H. Pratt, and G. B. Douglas. Forthcoming. Land Use and Site Design. Chapter 15 in Traveler Response to Transportation System Changes, TCRP Project B-12A, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Landis, J., and D. Loutzenheiser. 1995. BART@20: BART Access and Office Building Performance. Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California at Berkeley.

Mackett, R. L. 1985. Integrated Land Use: Transport Models. Transport Reviews, Vol. 5, No. 4, Oct.–Dec., pp. 325–343.

Meyer, M. D., and E. J. Miller. 2000. Urban Transportation Planning: A Decision-Oriented Approach. McGraw-Hill, New York.

National Association of Local Government Environmental Professionals. 1999. Profiles of Business Leadership on Smart Growth. Washington, D.C.

National Association of Realtors. 2001. The Public Voices Its Opinions and Priorities on Open Space. In On Common Ground, Washington, D.C., Summer.

Noland, R. B., and L. L. Lem. 2002. A Review of the Evidence for Induced Travel and Changes in Transportation and Environmental Policy in the US and the UK. Transportation Research D, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1–26.

NTI. 2000. Coordinating Transportation and Land Use: Course Manual. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.

1000 Friends of Oregon. 1997. Making the Connections: A Summary of the LUTRAQ Project. Vol. 7, Portland, Oreg., Feb.

Orfield, M. 2002. Metropolitics. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Payne-Maxie Consultants and Blayney-Dyett. 1980. The Land Use and Urban Development Impacts of Beltways Guidebook. U.S. Department of Transportation and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Powell, J. A. 2000. Race, Poverty, and Urban Sprawl. The Institute on Race and Poverty, University of Minnesota School of Law, Minneapolis.

Princeton Survey Research Associates. 2000. Straight Talk from Americans—2000. Pew Center for Civic Journalism.

Redmond, L. S., and P. L. Mokhtarian. 2001. Modeling Objective Mobility: The Impact of Travel-Related Attitudes, Personality and Lifestyle on Distance Traveled. Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Davis.

Shunk, G. 1995. Proceedings of a Conference on Land Use Modeling. Dallas, Tex.

Smart Growth America. 2000. Americans’ Attitudes About Growth Are Changing. In Greetings from Smart Growth America, Washington, D.C.

Spengler, E. H. 1930. Land Values in New York in Relation to Transit Facilities. Columbia University Press, New York.

STPP. 2001. Americans Flock to Transit, Ease Up on Gas Pedal. Press release. Washington, D.C., April.

Texas Transportation Institute. 1998. Urban Roadway Congestion: Annual Report 1998. College Station, Tex.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2000. Estimates of the United States Population: April 1, 1980 to July 1, 1999. Population Estimates Program, Population Division, updated May.

U.S. Congress. 1961. Final Report of the Highway Cost Allocation Study, Part VI: Studies of the Economic and Social Effects of Highway Improvement. House Document No. 72, 87th Congress, U.S. Government Printing Office.

USDA. 2000. 1997 National Resources Inventory. Natural Resources Conservation Service, revised Dec.

Warner, S. B. 1962. Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870–1900. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Webber, M. M. 1976. The BART Experience: What Have We Learned? Institute of Urban and Regional Development and Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

Wegener, M. 1987. Transport and Location in Integrated Spatial Models. In Transportation Planning in a Changing World, Aldershot, Hants, United Kingdom.

Weinberger, R. R. 2001. Light Rail Proximity: Benefit or Detriment in the Case of Santa Clara County, California? In Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 1747, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., pp. 104–113.