CHAPTER 7

FINANCING OF PALLIATIVE AND END-OF-LIFE CARE FOR CHILDREN AND THEIR FAMILIES

[Let me mention] the frustrations that we did have with insurance. You need to have a business degree, I think, to deal with these things.

Winona Kittiko, parent, 2001

Wearing my administrator’s hat, I myself see [hospital palliative care] programs as a major risk. They . . . require short-term renovation costs and continuing personnel costs, and invite concern about lost long-term opportunities: What if we had put a profitable cardiac [catheterization] unit into the same space or a chemo infusion center?”

Thomas J. Smith (Lyckholm et al., 2001)

Health insurance—whether public or private—has traditionally focused on acute care services intended to cure disease, prolong life, or restore functioning lost due to illness or injury. It has excluded most preventive services as well as extended care for long-term, chronic illness. Medicaid has been the major exception. From the outset, this federal-state program has covered many long-term care services for beneficiaries with serious chronic health problems and disabilities. Early on, it added a range of preventive services, particularly for children. Medicare and private insurers have gradually added coverage for various preventive services (e.g., screening mammography), influenced in part by contentions that such services could reduce subsequent spending on disease treatment. Medicare and most Medicaid programs and private insurers also now cover at least one form of supportive care—hospice—for patients who are dying.

Nevertheless, gaps and other problems in the financing of palliative and end-of-life services contribute to access and quality concerns for adults and children living with life-threatening conditions. Complete lack of insurance is an obvious problem. Yet, even when a person is insured, coverage limitations, financing methods and rules, and administrative practices can create incentives for undertreatment, overtreatment, inappropriate transitions between settings of care, inadequate coordination of care, and poor overall quality of care. Low levels of payment to providers can discourage them from providing certain treatments and from treating some patients at all.

Obtaining a good picture of financing for palliative and end-of-life care services for children is difficult. Unlike virtually all elderly Americans, children are covered not by a single insurance program (Medicare) but, instead, by thousands of private insurers and a multitude of state Medicaid and other public programs that have differing eligibility and coverage policies. These policies are poorly or not conveniently documented and constantly changing, so such information as is available on private health plans and Medicaid programs may be incomplete or out of date.1 Further, because death in childhood is relatively uncommon, data from surveys (e.g., of hospice and home care services) may not provide reliable estimates. Insofar as available data permit, this chapter

-

describes payment sources for palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care for children and their families;

-

reviews relevant coverage and reimbursement policies for private health plans and Medicaid; and

-

recommends directions for changes in coverage and reimbursement policies.

WHO PAYS FOR PALLIATIVE AND END OF LIFE CARE FOR CHILDREN?

General

Sources of Payment

Policymakers have long made children, especially poor and sick children, a special focus of programs that promote healthy growth and provide access to needed health services. At the national level, the creation of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau in 1935 (Title V of the Social Security Act) was an important affirmation of the federal government’s interest and involvement in services for pregnant women, infants, and “crippled” children (Gittler, 1998).2 Since then, the program has expanded its focus to include other children with serious chronic health problems. The creation of Medicaid in 1965 significantly expanded access to health insurance and health services for children in low-income families, whether or not they had medical problems. Recently, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) has sought to extend coverage for poor children through Medicaid expansions or other strategies.

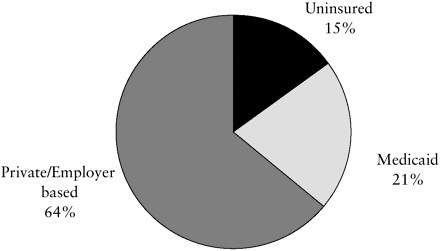

Most children (and adults) are, however, covered by private health plans sponsored by employers. As summarized in Figure 7.1, in 2000, almost two-thirds of this country’s 72 million children (under age 19) were covered by employment-based or other private health insurance (AHRQ, 2001b). An estimated 20 percent of children had public insurance (primarily Medicaid and then SCHIP).3 A significant proportion of children—some 15 percent of those under age 19—were not insured. (For those aged 19 to 24, the figure is 33 percent.)

National figures on coverage do not reflect the substantial variation across states. For example, in Maryland in 1997, approximately 78 percent

|

2 |

An earlier Maternity and Infancy Act, which was passed in 1921, expired in 1929. The Children’s Bureau dates back to 1912. In 1985, Congress changed the terminology for the relevant Title V components from “crippled children” to “children with special health care needs” to reflect expansions in the program’s focus and changing attitudes. (see www.ssa.gov/history/childb2.html and www.mchdata.net/LEARN_More/Title_V_History/title_v_history.html). |

|

3 |

Under special provisions, Medicare covers those diagnosed with end-stage renal disease who are insured under Social Security or who are spouses or dependent children of such insured persons. In 1997, approximately 2,200 individuals under age 15 were receiving Medicare-covered dialysis (see http://www.hcfa.gov/medicare/esrdtab1.htm). According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, about 600 children under age 18 received kidney transplants in 2000 (http://www.unos.org/Newsroom/critdata_transplants_age.htm#kidney). |

FIGURE 7.1 Source of health insurance coverage for children ages 0 to 18.

NOTE: Figure combines data reported separately for the 0–17 and the 18-year-old age groups.

SOURCE: Compiled from data from Center for Cost and Financing Studies, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, 2000.

of children were covered by private insurance, 6 percent by Medicaid, and 16 percent had no insurance (Tang et al., 2000). In neighboring West Virginia, the comparable figures are 54 percent, 35 percent, and 11 percent, respectively. Arizona, Alaska, and Texas had more than 25 percent of children uninsured compared to less than 8 percent in Hawaii, Minnesota, Vermont, and Washington state. These variations reflect a mix of factors including state economic conditions, immigration, demographics, and political choices about such matters as taxation and spending priorities.

In 1999, of children in poor families (at or below 100 percent of the poverty level or $13,290 for a family of three in that year), an estimated 26 percent were uninsured. Of children in near-poor families (up to 200 percent of the poverty level), an estimated 21 percent were uninsured (Broaddus and Ku, 2000).4 In 1999, an estimated 85 to 94 percent of low-income,

uninsured children were eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP, but their parents or guardians had not enrolled them (Broaddus and Ku, 2000; Dubay et al., 2002a). Approximately two-thirds of the eligible but uninsured children were eligible for Medicaid and the other third for SCHIP. Among children identified as eligible for Medicaid, participation in the program ranges from a high of 93 percent in Massachusetts to a low of 59 percent in Texas (Dubay et al., 2002b; see also HCFA/CMS, 2000g). For children with serious medical problems, hospital social workers or other health care personnel often assist low-income families in enrolling the child in Medicaid, SCHIP, or any other special programs. A recent survey indicated that from 1997 to 2001 the number of uninsured children (under age 18) dropped from 12.1 percent to 9.2 percent while the percentage of children reported to have difficulty getting care dropped from 6.3 to 5.1 percent during this period (Strunk and Cunningham, 2002).

Access to Care: More Than Just Insurance Coverage

Lack of insurance does not necessarily mean the lack of access to all health care, especially for children with life-threatening medical conditions. Uninsured children may have some care paid for or provided by their families, “safety-net providers,” philanthropy, and other sources, but they may also go without needed services. Improved financing of care is one cornerstone of improved access to care for children, including children and families living with life-threatening medical conditions (IOM, 1998; Lambrew, 2001).

When children are insured and parents are not, children may still suffer. For example, some research suggests that insured children are less likely to have preventive care if their parents are uninsured (Gifford et al., 2001). As a result, some federal and state insurance initiatives are also reaching out to parents. For example, states can apply for waivers of SCHIP or Medicaid requirements to cover parents directly or through subsidies for enrollment in employer-based plans (AHSRHP, 2001).

Variability in Coverage of Palliative, End-of-Life, and Bereavement Care

Coverage of end-of-life and palliative care services for children who die and their families varies tremendously, both across payer types (e.g., private insurance, Medicaid) and among payers of the same type. Regional variation in coverage policies and their day-to-day interpretation is substantial, as is variation by size and other characteristics of employers. Moving across a state border or changing jobs can result in substantial changes in services covered for seriously ill children and their families.

The next sections of this report review what is known about how three

major sources of insurance (private, Medicaid, and SCHIP) cover important palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement services. Other sources of funding for children’s care—including federal Title V programs, safety-net providers, philanthropy, family out-of-pocket payments, and clinical trials—are discussed briefly. The focus is on coverage of hospice, home health care, inpatient care, pharmaceuticals, psychosocial services, and respite care. Provider payment methods and levels and other important financing issues are discussed in subsequent sections.

Employment-Based and Other Private Insurance

General

As noted above, almost two-thirds of children in the United States are covered by private health insurance, mostly through plans sponsored by employers that also offer—usually for an additional charge—coverage for an employee’s family. Many employers, especially small, low-wage employers, do not offer health insurance, in part because their profit margins are slender and in part because premiums are typically much higher for small firms. Even when employers offer insurance, some employees do not “take up” coverage because the required employee contribution is too high or because better or less expensive coverage is available through a spouse.

Some self-employed and other parents are able to buy family coverage individually. These individuals tend to face high premiums, and those with past medical problems may have difficulty obtaining any coverage. Older children may be able to obtain coverage in their own right as an employee or college student. Some states have programs to help provide private insurance to uninsured individuals.

Summary data on coverage rates do not depict the extent of instability in employer-sponsored coverage. Insurance coverage for children and families may be interrupted or altered for a variety of reasons. Parents may lose their jobs or take new jobs that either offer coverage from different health plans or do not include health benefits at all.5 In addition, employers may change the scope of benefits they offer or switch health plans, which may mean changes in provider networks or administrative procedures. This can affect continuity of care, a particular concern for families with a seriously ill child. As discussed in Chapter 5, other employer-provided benefits, includ-

|

5 |

Federal law generally requires that firms with 20 or more employees allow eligible former employees and covered spouses and children to pay for continued coverage at group rates (actually, at 102 percent of the group premium) for up to 18 or 36 months, depending on the circumstances (http://www.dol.gov/dol/pwba/public/pubs/COBRA/cobra99.pdf). Not all individuals or families can, however, afford such continuation coverage. |

ing paid or unpaid leave, may help children with serious medical conditions and their families. Flexible spending accounts, funded with pre-tax dollars, can pay for health care services not covered by an employee’s health plan and for deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance that are required for covered services.

Many states have laws requiring that private health plans cover or offer coverage for a wide range of services (e.g., infertility treatments, breast implant removal), some of which (e.g., hospice, mental health care) are relevant to palliative and end-of-life care. Self-insured employers generally claim freedom from such requirements under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, commonly referred to as ERISA. Most large and many middle-sized employers are self-insured.

Private Insurance Coverage of Home Hospice Care

As an insurance benefit, hospice coverage normally includes home-based nursing care, physician services, physical or occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, medical social services, medical supplies and certain equipment, and prescription drugs. The benefit usually includes a limited amount of inpatient care if needed for respite or symptom management.

A study by Gabel and colleagues (1998) analyzed information about private hospice coverage from a national random sample of more than 1,500 employers with 200 or more employees each. It also drew on information from focus groups that included employee benefits managers and their insurance advisers. The researchers found that a substantial majority of employers surveyed (83 percent) offered formal hospice benefits. Most of the rest covered a similar range of services through high-cost case management programs that allow case managers discretion to pay for and assist in arranging services not otherwise covered by a health plan. Large employers were more likely to offer hospice benefits than were mid-size employers.

Many private insurance plans have adopted the hospice eligibility and coverage rules used by the Medicare program. Almost half of respondents to the survey by Gabel and colleagues reported that their health plan hospice benefit restricted eligibility to individuals with a life expectancy of six months or less. Another 30 percent did not know whether such a requirement existed in their plan. Unlike Medicare, 28 percent of the plans were reported to include an individual dollar cap on hospice benefits (e.g., $5,000), and 31 percent limited the length of stay.

A second study by Jackson and colleagues (2000) reported an analysis of booklets that summarized benefit plans for 70 large employers. According to these summaries, most employers (88 percent) offered hospice benefits. Most required a physician’s certification of a terminal illness, but only half specified a prognosis of six months or less of remaining life. Most plans

did not require cost sharing (e.g., paying a fixed amount per visit or a percentage of the charge) for the services, and the majority did not set lifetime day or dollar maximums. Further, in interviews with nine employer representatives, the researchers found more flexibility in the administration of benefits than was suggested by the written plan summaries. The typical comment was that waiving certain benefit restrictions on hospice care was “the right thing to do” (Jackson et al., 2000, p. 4).

Based on their interviews, Jackson and colleagues categorized the nine employer plans as following a Medicare-like model, a comprehensive model, or an unbundled approach. Only two plans followed the Medicare approach of requiring the suspension of curative treatment. Two of the three managed care plans used an unbundled approach, placing the plan’s case manager in a central position to enroll individuals in hospice and approve individual care plans and services.

In contrast to the studies described above, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, which are based on a large sample of large- and medium-sized private employers (those with 100 or more workers), showed lower rates of hospice coverage in 1997—just 60 percent across all categories (BLS, 1999). The BLS data indicated that health maintenance organization (HMO) plans were more likely to cover hospice than other plans (69 percent versus 43 percent, respectively). A separate BLS survey of state and local government employers reported that 64 percent offered hospice coverage in 1998 (BLS, 2000).

No individual employer example can represent the variability described above, but as an illustration, Table 7.1 presents the hospice coverage listed in the 2002 benefits description for the large Blue Cross Blue Shield options for federal employees. Among other restrictions, the plan requires prior approval. Coverage excludes bereavement services but includes inpatient care to provide brief respite for family members. As with all the other health plans offered to federal employees, the benefit structure is approved and sometimes directed by the federal Office of Personnel Management rather than unilaterally determined by the insurer or health plan.

Private Insurance Coverage of Home Health Care

Health plan rules, licensure regulations, and physician and family reluctance to accept hospice can make home hospice coverage less helpful than it might otherwise be for children who die and their families. For these children and families, home health care providers, including those affiliated with hospices, may offer an array of supportive medical and other services including home nursing care. Also, home health agencies may start providing care before a child is recognized as dying. Continuity with the same organization and personnel may be reassuring to a child and family, even

TABLE 7.1 2002 Hospice Coverage Benefits for Blue Cross Blue Shield Federal Employees Health Insurance Plan

|

Hospice Care |

You Pay–Standard Option |

You Pay–Basic Option |

|

Hospice care is an integrated set of services and supplies designed to provide palliative and supportive care to terminally ill patients in their homes. We provide the following home hospice care benefits for members with a life expectancy of six months or less when prior approval is obtained from the Local Plan and the home hospice agency is approved by the Local Plan: • Physician visits • Nursing care • Medical social services • Physical therapy • Services of home health aides • Durable medical equipment rental • Prescription drugs • Medical supplies |

Nothing |

Nothing |

|

Inpatient hospice for members receiving home hospice care benefits: Benefits are provided |

Preferred: $100 per admission copayment |

Preferred: $100 per day copayment up to $500 per admission |

when home hospice care is covered by the family’s health plan and would otherwise be acceptable to parents.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 85 percent of large and medium-sized private employers provided some home health care coverage (BLS, 1999). HMO plans were more likely to cover these services than other plans (93 percent versus 81 percent).

Health plans that pay for home health care may, however, exclude certain services that are often or sometimes included in hospice benefits (e.g., physical therapy, bereavement care). Moreover, state licensure requirements may restrict licensed home health care providers from providing certain end-of-life services such as bereavement care. In addition, employersponsored plans often limit coverage for home health care to a certain

|

Hospice Care |

You Pay–Standard Option |

You Pay–Basic Option |

|

for up to five (5) consecutive days in a hospice inpatient facility. Each inpatient stay must be separated by at least 21 days. These covered inpatient hospice benefits are available only when inpatient services are necessary to: • Control pain and manage the patient’s symptoms; or • provide an interval of relief (respite) to the family Note: You are responsible for making sure that the home hospice care provider has received prior approval from the Local Plan. Please check with your Local Plan and/or your PPO directory for listings of approved agencies. |

Member: $300 per admission copayment |

Member/Non-member: You pay all charges |

|

Non-member: $300 per admission copayment plus 30% of the Plan allowance, and any remaining balance after our payment |

|

|

|

Not covered: Homemaker or bereavement services |

All charges |

All charges |

|

NOTE: PPO = preferred provider organization. SOURCE: Blue Cross and Blue Shield, 2002 Service Benefit Plan, p. 63, http://www.fepblue.org/pdf/2002sbp.pdf (emphasis in the original). |

||

number of nursing or therapy visits (e.g., 60 visits per year) or require that care be expected to lead to improvement in the health condition. Thus, services needed by chronically or terminally ill patients on an ongoing basis such as nursing visits, respiratory therapy, and physical therapy may be limited or excluded altogether under an employer’s plan.

In one study of Medicare financing of end-of-life services, end-of-life care providers (including home health agencies as well as hospices) reported the need for end-of-life consults from a hospice team for dying patients not enrolled in hospice in order to assist in symptom management and end-of-life care planning (Huskamp et al., 2001). Such consultative services for a patient receiving home health care would not ordinarily be covered by private health insurance (unless the health plan waived coverage restric-

tions as described earlier). In these situations, lack of coverage for consultations by hospice or other palliative care experts may lead to avoidable pain and other suffering for dying children and their families.

As discussed in Chapter 6, telemedicine could help extend information and advice to support home health providers for children and families in smaller communities and rural areas. Private insurer coverage for telemedicine services is limited (OAT, 2001).

Private Insurance Coverage of Inpatient Hospital Care

The centerpiece of most private health insurance has traditionally been coverage for inpatient hospital services, which continue to be generously covered compared to other services. Thus, much of the emergency, intensive, and palliative care—including nursing care, diagnostic tests, medications, and many other services—that is provided to children with life-threatening conditions is routinely covered.

If, however, patients, families, and physicians choose to forgo curative or life-prolonging care in favor of inpatient care that is exclusively but intensively palliative, some health plans may refuse to pay if the plan limits inpatient coverage to treatment intended to cure or restore function. (As discussed later, even if coverage is not an issue, the case-based and other payment systems for hospitals are based on data and assumptions that exclude modern palliative services, which is a disincentive for hospitals to provide these services.) The committee found no systematic information on the extent to which coverage is approved or denied when inpatient pediatric care is exclusively palliative.

Private Insurance Coverage of Outpatient Prescription Drugs

Unlike Medicare, most employers that offer insurance to employees cover outpatient prescription drugs, subject to various limitations such as cost sharing requirements. Information from a large survey of employers indicates that nearly all employees (96 percent) covered by employer health plans had prescription drug coverage in 1997 (Marquis and Long, 2000). Even for small employers and low-wage employers, more than 85 percent provided outpatient drug coverage.

BLS data for medium- and large-sized private employers also show very high levels of employer coverage of outpatient prescription drugs (BLS, 1999). For nearly 80 percent of covered workers, the level of cost sharing for prescription drugs was no higher than for physician services; about 18 percent faced higher cost sharing for drugs.

Spending for prescription drugs has increased dramatically during the last decade. Health plans have responded by increasing the level of cost

sharing and using pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to manage drug benefits separate from their general health plan or plans (Cook et al., 2000; Mays et al., 2001). Elements of these programs typically include negotiated price discounts with manufacturers, a mail order service, drug utilization review to detect inappropriate prescribing patterns, processing of drug claims, and formulary management. In an insurance context, a formulary is a list of covered drugs.

Most HMOs, preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and PBMs report using some kind of formulary that sets forth what prescription drugs are routinely covered and what exceptions are permitted under specified circumstances (Wyeth-Ayerst, 1999). Some plans have closed formularies, meaning that they refuse to pay for drugs not on the list. These plans often offer an exemption process that allows coverage of an unlisted drug if a patient’s physician provides documentation that the particular drug is medically necessary for the patient. The flexibility of this “exemption” process varies across plans.

A three-tier approach to pharmacy benefits has become increasingly common. Although the specifics vary, the first tier, with the lowest copayments, typically consists of generic drugs (e.g., generic amoxicillin). The second tier consists of brand-name drugs that the organization considers to be safe, effective, and reasonably priced. The third tier consists of nonpreferred brand drugs, for example, those that the plan judges not to provide better outcomes for their extra cost. Drugs considered to be primarily “lifestyle-enhancing” in nature (e.g., Propecia for baldness, Viagra for sexual dysfunction) may also be included in the third tier, or they may be excluded from coverage altogether.

Depending on the values, knowledge, and choices of the health plan and the PBM about, for example, pain medications, these programs could make effective drugs more or less costly for children with serious medical problems (Motheral and Henderson, 2000; Motheral and Fairman, 2001). Formulary provisions could also lead parents and physicians to select less costly drugs that are also less effective for a particular child given, for example, his or her ability to metabolize certain opioids or other drugs.6

A separate and often controversial issue with employment-based health plans is the introduction of therapeutic substitution policies. Such policies

allow pharmacists to substitute an alternative drug (a different chemical entity) considered therapeutically equivalent7 in place of the drug prescribed by the physician. Such policies are controversial because designations of therapeutic equivalence may not adequately reflect the physiological variability that a clinician may recognize in an individual patient’s response to a drug but that has not yet been demonstrated scientifically.

Private Insurance Coverage of Psychosocial, Respite, and Other Services

Most employer health plans provide coverage for mental health services that may help children with life-threatening medical problems and assist families before and after a child’s death. Some health plans cover (i.e., allow direct billing by and payment to) for services provided by a clinical psychologist or clinical social worker. Child-life specialists, art therapists, music therapists, chaplains, or other personnel are rarely if ever reimbursed directly for their professional services.

Except through hospice, health insurance plans generally do not cover bereavement care as such, although insured parents or siblings may be covered for services to treat depression, anxiety, and certain other emotional problems experienced during bereavement. One disadvantage of coverage contingent on these diagnoses is that bereaved family members may receive a diagnostic label that could jeopardize their future ability to qualify for health insurance, especially individually purchased insurance. Even as part of their hospice benefits, private health plans do not universally cover

|

7 |

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “classifies as therapeutically equivalent those products that meet the following general criteria: (1) they are approved as safe and effective; (2) they are pharmaceutical equivalents in that they (a) contain identical amounts of the same active drug ingredient in the same dosage form and route of administration, and (b) meet compendial or other applicable standards of strength, quality, purity, and identity; (3) they are bioequivalent in that (a) they do not present a known or potential bioequivalence problem, and they meet an acceptable in vitro standard, or (b) if they do present such a known or potential problem, they are shown to meet an appropriate bioequivalence standard; (4) they are adequately labeled; and (5) they are manufactured in compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations. The concept of therapeutic equivalence, as used to develop the List, applies only to drug products containing the same active ingredient(s) and does not encompass a comparison of different therapeutic agents used for the same condition (e.g., propoxyphene hydrochloride vs. pentazocine hydrochloride for the treatment of pain). Any drug product in the List repackaged and/or distributed by other than the application holder is considered to be therapeutically equivalent to the application holder’s drug product even if the application holder’s drug product is single source or coded as non-equivalent (e.g., BN). Also, distributors or repackagers of an application holder’s drug product are considered to have the same code as the application holder. Therapeutic equivalence determinations are not made for unapproved, off-label indications.” (FDA Orange Book; http://www.fda.gov/cder/ob/docs/preface/ecpreface.htm#TherapeuticEquivalence-RelatedTerms). |

bereavement counseling for family members. (See, e.g., Table 7.1 and other illustrative examples at Presbyterian Health, 2001; and Aetna Insurance, 2001).

Traditionally, most private insurance plans have imposed special benefit limits (e.g., higher copayments or coinsurance, caps on the number of visits or total payments during a year or lifetime) for mental health services that they did not apply to other types of covered health care services. In the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-204, reauthorized for one year in 2001), Congress required that if an employee health benefit plan covers mental illness, the plan cannot set lower annual or lifetime spending limits for mental health services than those set for services for physical or surgical illnesses (Otten, 1998).8

Employer plans may cover limited amounts of respite care as part of hospice benefits. Otherwise, benefits for respite care appear to be rare.9 Most discussions of expansion in respite services focus on public programs (see, e.g., Silberberg, 2001). When a child has a severe chronic condition, families may bear extraordinary physical, emotional, and financial burdens because neither regular paid assistance nor occasional respite care is covered.

Innovations in Coverage

Some private health plans have developed or are testing innovative programs of coverage for palliative and end-of-life care focused on adults. For example, a recent publication sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) described nine programs involving Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans in various parts of the country (Butler and Twohig, 2001).

Two plans (Regence Blue Shield and Premera Blue Cross) participated with the state of Washington in an RWJF-sponsored research project led by the Children’s Hospital and Medical Center of Seattle. Regence’s program covered any child under age 21 in a health plan that included a benefits management clause that allows waivers of certain plan restrictions under certain circumstances. After the project began, the plan added payment for

a child’s participation in well-designed clinical research as a case management option, and it is developing a palliative care “add-on” feature to offer as part of future benefits packages. The Premera program was designed to assist early access to hospice care, promote active case management, and encourage creative use of home care benefits. Both plans used a “decision-making tool” (developed by medical ethicists at the University of Washington) that provided a comprehensive framework for discussing all aspects of a child’s care and taking into account medical circumstances, family preferences and situations, quality of life, and financial issues. Challenges identified by the two health plans included early identification of children and families who might benefit from hospice care and changing the relationship with hospices from adversarial to cooperative. Cost and satisfaction data are still being collected and analyzed.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Montana is participating in a multisite project, this one testing the Advanced Illness Coordinated Care model that was developed by the Life Institute and is described in its pediatric format in Chapter 6. This program is unusual because the plan will fund participation in the program of 120 people under age 65, whether or not they have coverage from the plan. The program is organized around six to nine home visits made by case managers to individuals who have a fatal diagnosis but do not meet hospice criteria. The case management services are paid for by the plan under a contract with the Life Institute. The plan anticipates that the discussions will lead to some cost savings based on advance care planning and avoidable hospitalization.

In addition, as one outgrowth of its involvement in community initiatives to improve end-of-life care, the Blue Cross Blue Shield plan (Excellus) in Rochester, New York, recently established payment for palliative care consultations by physicians certified in hospice and palliative medicine (BCBSRA, 2002). The plan also has established a program called CompassionNet aimed at children who meet one of the following criteria:

-

a diagnosis of a potentially life threatening illness,

-

two unplanned hospitalizations in the preceding six months (other than for asthma),

-

an acute exacerbation of a chronic illness that creates an extreme risk, or

-

a prognosis of three years of life or less.

Medicaid

General

The state–federal Medicaid program is a critical source of funding for services to low-income children. It covers large numbers of children with

chronic illnesses and serious disabilities. 10 Consistent with Title XIX of the Social Security Act, federal law establishes requirements for states that participate in Medicaid, which all states now do. Among other services, states must cover

-

children ages 6 to 18 with family incomes at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (in 2001, $14,630 for a family of three) (to be fully phased in as of 2002) and

-

children under age 6 and pregnant women with family incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level.

About 80 percent of Medicaid-enrolled children are covered under the mandatory categories. The remainder, whose families have higher incomes, are covered at the discretion of states. The optional coverage categories for children include

-

infants up to age 1 and pregnant women, who are not covered under the mandatory rules and whose family income is no more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level (with the specific percentage set by each state),

-

children under age 21 who meet the income and resources requirements for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) that were in effect in their state on July 16, 1996, and

-

children under age 18 who qualify under complicated federal and state rules as “medically needy.”

In general, the option for “medically needy” children allows a state to extend Medicaid coverage when the family’s income is too high to qualify otherwise but the child has very high medical expenses. The family “spends down” to eligibility because the child’s medical expenses reduce the family’s income below the state Medicaid maximum. If a state has a medically needy program, it must include certain children under age 18 and pregnant women who would otherwise be eligible as “categorically needy” under the optional coverage requirements.11

Overall, children comprise just over half of Medicaid enrollees, roughly 21 million out of 40 million total in 1998. Reflecting their generally good

|

10 |

Unless otherwise indicated, data in this section come from HCFA/CMS (2000b; 2001d). |

|

11 |

States may also allow families to establish eligibility as medically needy by paying monthly premiums to the state in an amount equal to the difference between family income (reduced by unpaid expenses, if any, incurred for medical care in previous months) and the income eligibility standard (HCFA/CMS, 1997; http://www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/meligib.htm). |

health, however, children accounted for only about 14 percent of Medicaid expenditures of nearly $170 billion dollars that year (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2001).

Within federal requirements (and monitoring capabilities), states have considerable discretion to establish eligibility for Medicaid, determine the scope of services covered (e.g., number of physician office visits during a year), set levels of enrollee cost sharing for adults except pregnant women (e.g., $5 per office visit), establish methods and rates of payment for services, and administer the program. Federal law requires, however, that state Medicaid programs cover a generally broader array of services for children than for adults. The major vehicle for achieving this objective was 1969 legislation (P.L. 90-248) and subsequent amendments requiring coverage for early periodic screening, detection, and treatment (EPSDT) services for those under age 21. In 1989, Congress specifically defined the required EPSDT benefits (P.L. 101-239). It also required states to provide necessary health care, diagnostic services, treatment, and other measures to “correct or ameliorate defects and physical and mental illnesses and conditions discovered by the screening services, whether or not such services are covered under the State plan” (42 USC §1396d(r)(5)). (See also HCFA/CMS, 2001c). Some states responded by expanding their list of covered services; other states provided that decisions about services not usually covered be made on a case-by-case basis (NASMD, 1999). Box 7.1 lists the services specified in the 1989 legislation.

The EPSDT provisions would seem to require states to provide children (including those with life-threatening medical conditions) access to almost any medical and supportive service identified as needed through screening.12 In practice, reflecting the potentially large additional costs they would face, states have often been slow to implement EPSDT provisions or have been very restrictive in their interpretations of the provisions (Perkins, 1999; O’Connell and Watson, 2001). These responses have prompted a number of lawsuits, several of which have focused on services for children with mental or developmental disabilities, including those on waiting lists for

|

12 |

Screening has been unconventionally defined in this context to include certain visits prompted by symptoms. “Interperiodic EPSDT Screening Services are physical, mental, dental, vision or hearing screens described in subsection (b) that, in furtherance of the preventive purpose of the EPSDT benefit: (i) occur at a time other than the applicable periodic EPSDT screening services referenced in subparagraph (A); and (ii) is requested by an enrolled child’s family or caregiver or by an individual who comes into regular contact with the child and who suspects the existence of a physical, mental or developmental health problem (or possible worsening of a preexisting physical, mental or developmental health condition)”(CHSRP, 1999, http://www.gwumc.edu/chpr/sps/part1.htm). See also the State Medicaid Manual discussion of medically necessary interperiodic screening (HCFA/CMS Publication 45; http://www.hcfa.gov/pubforms/progman.htm). |

home and community-based services. In any case, it is not clear what EPSDT services are effectively available to Medicaid-covered children in each state.

Adding to the complexity of summarizing state Medicaid coverage, most states have been rapidly enrolling beneficiaries in managed care programs, whose specific coverage and other policies also vary. Under Section 1915(b) waivers of “freedom-of-choice” provisions of Title XIX, states can require Medicaid enrollees to enroll in comprehensive or specialized (e.g., behavioral health) managed care plans (HCFA/CMS, 2001a). The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 allows states to institute mandatory enrollment through an amendment to their state plan and thereby bypass this waiver process. One exception is that states must still get a waiver to require managed care enrollment for children with special health care needs, a group that will include some children with fatal or potentially fatal medical conditions (Gruttadaro et al., 2001). This restriction recognizes the particular care requirements and vulnerabilities of special needs children.

In 2000, 56 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in some form of managed care, up from 40 percent in 1996 (HCFA/CMS, 2000b).13 These percentages include some who were enrolled in more than one kind of plan. In 1998, the percentage of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans ranged from zero in Alaska and Wyoming to more than 75 percent in a dozen states (HCFA/CMS, 2000b). More than 55 percent of all Medicaid managed care enrollees were children.

In addition to the freedom-of-choice waivers, states can also obtain waivers that allow them to include additional populations or services not otherwise covered under Medicaid. As discussed further below, under Section 1915(c) waivers, states can provide additional home and community-

|

Box 7.1

|

based services as an alternative to institutional care (Smith et al., 2000).14 Waiver services do not have to be provided on a statewide basis or to all those with similar levels of need.

Under yet another waiver authority (Section 1115), states can undertake demonstration projects to test innovative program ideas or service concepts. As noted in Chapter 1 and discussed further below, Congress has authorized several state demonstration projects to test innovative approaches to providing comprehensive palliative and end-of-life care for

SOURCE: Perkins, 1999. |

children and families. Eligibility for services provided under this demonstration waiver authority is not restricted to low-income families. A condition for both Section 1915(c) and Section 1115 waivers is that they be budget neutral (i.e., not generate costs to the federal government more than occur without the waiver).

As discussed in a later section on professional and provider payment, Medicaid coverage for specific services is less an issue for many physicians, hospitals, and Medicaid enrollees than is the level and predictability of payments. A significant fraction of physicians do not accept Medicaid patients because payment levels are low and claims administration can be frustratingly inconsistent (Yudowsky et al., 2000; see also AAP, 1999d). This can result in access problems for children covered by Medicaid.

Medicaid Coverage of Home Hospice

Under federal Medicaid requirements, hospice is an optional benefit for adults. Most state Medicaid programs include hospice, but programs in Connecticut, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Dakota do not (Tilly and Weiner, 2001). For children, however, the 1989 EPSDT amendments cited earlier include hospice as a covered service. Therefore, children should have coverage for hospice even in states that do not provide hospice coverage to adult Medicaid enrollees.

The Medicaid hospice benefit follows the Medicare benefit in defining covered services, payment categories, and payment rates. Like Medicare enrollees, Medicaid enrollees must be certified as having a life expectancy of six months or less and must agree to forgo curative treatment (interpreted to include life-prolonging therapies) of their terminal illness in order to be eligible for the hospice benefit (MedPAC, 2002). Even when children are enrolled in Medicaid, hospice services may not be covered because the physician is unable or reluctant to certify a six-month prognosis. As discussed in Chapter 4, determining prognosis is even more difficult and uncertain for children than for adults. Also, families seeking assistance from hospice may still want the option of potentially life-prolonging interventions for their child. Medicaid home health benefits (discussed below) may cover some but not all of the services provided by hospices.

Although Medicaid beneficiaries have to forgo curative care to receive hospice benefits, federal law no longer requires that Medicaid beneficiaries receiving hospice care give up other supportive Medicaid services. Specifically, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (P.L.101-508) allows “payment for Medicaid services related to the treatment of the terminal condition and other medical services that would be equivalent to or duplicative of hospice care, so long as the services would not be covered under the Medicare hospice program. This means that Medicaid can cover certain services which Medicare does not cover” (HCFA/CMS, 2001b).

Nonetheless, it appears that some state Medicaid programs (e.g., New York) may force families to choose between hospice and more benefits for home and community-based services (Tilly and Weiner, 2001). Hospice personnel have repeatedly mentioned this as a concern in discussions with committee members and staff. The apparent divergence between federal policy and some state practice requires further attention as an inappropriate barrier to needed services for dying children.

In addition, Huskamp and colleagues (2001) have noted access problems for some high-cost hospice patients (e.g., those requiring expensive pain medications, blood transfusions15) enrolled in Medicare. Providers

reported that hospices would not enroll some patients because the hospice felt it could not afford to provide the high-cost services needed by a patient, given the Medicare (and Medicaid) per diem rates for hospice care. Alternatively, patients might be enrolled under the condition that certain high-cost items would not be provided by the hospice. The extent to which Medicaid patients—adults or children—experience this kind of access problem warrants investigation.

Medicaid Coverage of Home Health Care

A child’s eligibility for home care services under Medicaid can be difficult to determine given the complexity of federal Medicaid provisions and the variability in state Medicaid policies (see, e.g., Smith et al., 2000). Under federal law, required home health services for eligible beneficiaries include nursing care, home health aides, and medical supplies and equipment.16 Optional home health services include physical and occupational therapy. States have the option to cover personal care services, including assistance with bathing, dressing, and other routine daily activities.

Nearly all state Medicaid programs also provide some home care coverage under Section 1915(c) waivers that—as noted earlier—encourage a wide range of home and community-based services as an alternative to institutional care. The federal waiver provisions specifically mention home health, personal care, case management, respite care, adult day health services, habilitation services, and homemaker services. Eligibility for services provided to children under this waiver authority is not necessarily restricted to low-income families, but coverage need not be state wide, and the groups targeted for assistance may be quite narrow (e.g., persons with brain injuries).

Again, notwithstanding general Medicaid policies, EPSDT provisions would appear to require that a range of home care and home health services

be covered for children for whom such services are necessary. Also, as discussed below, other federal and state programs—primarily those funded by Title V—may assist with home and other services for children with special health care needs and their families. Medicaid coverage for telemedicine services in the home is limited. Compared to private insurers, however, states appear to have been somewhat more receptive to arguments for such coverage (OAT, 2001; see also http://www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/telemed.htm).

Medicaid Coverage of Inpatient Hospital Care

As is the case for private insurance, much of the emergency, intensive, and palliative care provided to children who die is covered as an inpatient service. The EPSDT services listed earlier in Box 7.1 do not include inpatient palliative care specifically, but EPSDT coverage requirements would seem to extend to almost any medical and supportive service identified as needed by a child. The committee found no information on coverage in practice for hospitalized children receiving only palliative services. The same kinds of reimbursement issues mentioned in the review of private coverage of inpatient palliative services apply in a general sense to Medicaid and are discussed further below.

Medicaid Coverage of Outpatient Prescription Drugs

Prescription drug coverage is optional for adults covered by Medicaid, but federal EPSDT policy requires coverage for children and also prohibits cost-sharing requirements (Bruen, 2000, 2002). Some states set no restrictions on the number of covered prescriptions for children, whereas others require prior authorization once a numerical limit is reached. For example, a South Carolina survey reported that five of eight southeastern states had no restrictions on the number of prescriptions for children, but three required preauthorization for prescriptions above a specified number (e.g., six per month in Georgia and North Carolina) (Legislative Audit Council, 2000). Limits on the number of prescriptions covered could create a barrier to effective symptom management for children with life-threatening medical problems and multiple or difficult symptoms.17

Federal legislation passed in 1993 (P.L. 103-66) allowed states to institute a number of restrictions on coverage of prescription drugs, including

|

17 |

As discussed in Chapter 10, many drugs approved for use with adults do not have dosing information for children, and recent legislation includes incentives and requirements to stimulate the research needed to provide such information. |

prior authorization requirements and closed formularies (Kaiser Commission, 2001).18 If a drug is excluded from a formulary, patients must still be able to seek coverage through a prior approval process. Several state Medicaid programs (e.g., Michigan, Florida) recently announced an intention to implement a closed formulary (Bruen, 2002). As is true for private health plans, one goal of formulary implementation is to negotiate lower drug prices or additional services (e.g., chronic disease management programs in Florida) with manufacturers.

How restrictive closed Medicaid formularies are or will be is still unclear, as is how they may affect children with life-threatening medical conditions and their families. Their restrictiveness will depend on the burden imposed by the prior approval process and on the extent to which the formulary includes an adequate number and choice of drugs effective for the palliation of pain and other symptoms.

Managed care introduces another complication for assessments of outpatient prescription drug coverage. A 1999 report on Medicaid formularies concluded that “some states do not monitor to see whether managed care organizations are assuring that Medicaid recipients receive the Medicaid pharmacy benefit. Since often only a closed formulary is available to their commercial members, providers [managed care plans] may not treat Medicaid recipients differently” (Bazelon, 1999, online, no page number).

Legislation in 1990 (P.L.101-508) required states to develop retrospective and prospective Medicaid drug utilization review programs. A retrospective program could, for example, involve profiling of providers in an attempt to reduce inappropriate prescribing patterns. A prospective program could involve the use of automated systems that produce an alert when prescriptions might result in drug–drug interactions for a patient. The goals of these programs can include monitoring safety and quality of care as well as cost containment (Kaiser Commission, 2001). The effects on children living with life-threatening conditions could be positive or negative depending on which drugs were monitored and what safety or quality criteria were used.

Medicaid Coverage of Psychosocial, Respite, and Other Services

State Medicaid programs are required to cover a broader range of mental health services for children than for adults. Most attention has

focused on EPSDT-required services for the early identification and treatment of children’s mental health problems and on long-term services for children with developmental disabilities or mental illness.

A number of different categories of professionals provide mental health services, but state policies vary on whether they directly reimburse psychologists, social workers, clinical nurse specialists (psychiatric), and other nonphysicians for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. According to a 1995 analysis by the American Psychological Association, 42 states allowed direct payment to psychologists for EPSDT services (APA, 1995).

With increasing numbers of children enrolled in managed care plans, scrutiny of these plans includes contract provisions and plan practices (e.g., prior authorization based on “medical necessity” determinations) that may affect the availability and quality of mental health services for children, especially those with special needs (see, e.g., NIMH, 1998; Stroul et al., 1998). Scrutiny is also being directed at the practices of specialized managed behavioral health organizations into which states have directed Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health problems. Some studies suggest that families tend to have difficulties getting timely referrals from Medicaid managed care plans for mental health services—even short-term services— for children with special needs (see, e.g., Fox et al., 2000).

Although problems with Medicaid coverage of mental health services will affect some children who die and their families, they do not appear to be high-priority concerns for this population. Clinicians and families are generally focused on other issues.

Bereavement services for family members of a child who dies are not explicitly covered by Medicaid outside the hospice benefit. (As discussed later, payment for such services is included in the per diem payments to hospices, which end with the patient’s death.) A parent or sibling covered by Medicaid in his or her own right might, however, be able to receive supportive mental health services upon referral for a diagnosis of depression or certain other emotional problems.

As Box 7.1 indicates, state Medicaid programs are not required under federal law to provide respite care, which offers family members rest and relief from the demands of caring at home for a child with major health care needs. Some states have applied for waivers to cover such services, but these are usually limited to a subset of diagnoses or conditions (e.g., severe mental retardation) (see, e.g., http://ddd.state.wy.us/Documents/kathy1.htm and http://www.dhs.state.tx.us/programs/communitycare/mdcp/services.html). In reality, Medicaid in-home services for a child may provide respite to the child’s family caregivers, but this is not their explicit purpose.

Innovations in Medicaid Coverage

In 1999, Congress appropriated funds for a series of demonstration projects to support the development of children’s hospice programs that provide integrated medical, social, and other services to children with life-threatening medical conditions (CHI, 2002). A major task for these projects, called Programs for All-Inclusive Care for Children and their Families (PACC), is to identify obstacles to such integrated care that are related to Medicaid and other regulations. In its solicitation of proposals from these states (HCFA/CMS, 2000c), the government described the most burdensome obstacles to pediatric palliative care:

-

requirements that limit hospice eligibility to children certified by a physician as being within six months of death;

-

regulatory limits on the array of services that a child may need, including skilled, intermittent, and 24-hour nursing care, respite care, music and other therapies designed to meet children’s developmental needs, and bereavement care;

-

payment limits that discourage hospices from accepting children who require expensive care;

-

waiver program provisions (e.g., requirements that a child needs an institutional level of care) that are not fitted to the needs of children who could benefit from hospice care; and

-

EPSDT programs that are inconsistent or too narrow.

The goals of the demonstration projects include (1) identifying children and families who could benefit from better integration and coordination of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement services; (2) devising integrated care strategies and identifying necessary waivers of restrictive regulations; (3) reducing hospital use by increasing services in the community; and (4) increasing awareness of state officials, providers, and health care professionals of unmet needs and stimulating interest in further initiatives to meet those needs. Projects must show that the programs are not expected to increase a state’s Medicaid costs.

As specified in the appropriations conference agreement for FY 2000, the five initial projects are located in Florida, Kentucky, New York, Utah, and Virginia. A project in Colorado has since been approved. The projects differ in scope and strategies (CHI, 2002). Appendix H describes the approach in New York state to developing the demonstration project.

State Children’s Health Insurance Program

Congress created the State Children’s Health Insurance Program in 1997 as Title XXI of the Social Security Act.19 The objective was to increase health insurance coverage for lower-income children through Medicaid expansions or creation of separate state programs or both. (If a child is legally eligible under a state’s Medicaid program requirements, he or she is supposed to be enrolled in Medicaid as such.)

With federal matching funds, states can extend coverage to children in families with incomes that are 200 percent of the federal poverty level. For states that had already expanded Medicaid eligibility to optional groups, the law raised the income threshold to 50 percent above the state’s existing limit. Certain technical actions (i.e., use of “income disregards” allowed for in Medicaid under Section 1931 of Title XIX) can allow other states to exceed the 200 percent figures (AHSRHP, 2001). State SCHIP programs are, like state Medicaid programs, highly variable.

Separate SCHIP programs may or may not provide the same covered benefits as the state Medicaid program and may or may not use state-approved Medicaid managed care plans to provide services. A recent analysis indicated that “among the 34 states with separately administered SCHIP programs in effect in 2000, 32 states use coverage exclusions that would not be permissible in Medicaid” (Rosenbaum et al., 2001, p. 2). Services that tended to be excluded from separate SCHIP programs were hospice, case management services, and home and community-based services. Depending on the availability of other support, the result could be inadequate palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Also, if the state creates a separate SCHIP program, it is not precluded—as it would be for its Medicaid program—from requiring copayments.

For states with separate SCHIP programs, coverage may be part of the basic program or part of a program designed specifically for children with special needs. Some state programs, for example, Wisconsin’s BadgerCare program, also offer coverage to low-income uninsured parents who have a child under age 19 living with them (see http://www.dhfs.state.wi.us/badgercare).

|

19 |

For general information about SCHIP, several Web sites provide useful descriptions or analyses including CMS/HCFA (http://www.hcfa.gov/init/children.htm); George Washington University’s Center for Health Services Research and Policy (http://gwhealthpolicy.org); American Academy of Pediatrics (http://www.aap.org/advocacy/schip.htm); and American Public Health Association (http://www.apha.org/ppp/schip/); and Health Services Research (http://www.hsrnet.com/pubs/pub04.htm). |

Other Sources of Financing

Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grants

In addition to public insurance programs such as Medicaid and SCHIP, Title V block grant programs in each state provide services directly to a broad range of chronically ill children (Gittler, 1998; MCHB, 1998).20 In 1989, Congress required state Title V programs for children with special needs “to provide and promote family-centered, community-based, coordinated care . . . and to facilitate the development of community-based systems of services for such children and their families” (MCHB, 2000b, online, no page number; P.L. 101-239).

As discussed in Chapter 2, children with special needs are those who have or are at increased risk of a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. Children covered by Title V programs have conditions that tend to fall into three broad, overlapping groups: (1) developmental disabilities or delays (e.g., mental retardation); (2) chronic illnesses or ongoing medical disorders (e.g., diabetes, severe asthma); and (3) emotional or behavioral problems (e.g., attention deficit disorder). Depending on state eligibility criteria, children who have diagnoses such as fatal neurodegenerative diseases and certain cancers could be eligible for Title V services. Overall, however, most children covered by Title V programs have chronic conditions and disabilities that are not usually expected to lead to death in childhood, and the programs are not explicitly intended to provide or assist end-of-life care.

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau administers the federal Title V program. It conceptualizes Title V-supported activities as a “pyramid” consisting of (1) direct personal services, (2) enabling services that assist children and families in obtaining coverage or services, (3) population-based preventive services, and (4) infrastructure-building activities (e.g., support for information systems, standards development, program evaluation). One long-standing positive feature of state programs for children with special health care needs is their concern with the organization, coordination, and availability of services (Ireys, 1996).

Children with special health care needs may be identified for assistance in many ways, including family inquiries about the availability of assistance, referral by physicians and other care providers, and state outreach

programs. In addition, when the Social Security Administration determines that a child under age 18 is eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI),21 the child and family are referred to state programs for children with special health care needs for assistance in securing needed services and enrolling children in Medicaid. In some states, Medicaid enrollment for children with SSI is automatic.

Within the requirements of federal law, states have considerable discretion to establish the scope and organization of programs for children with special health care needs. They have different criteria for financial eligibility, provide different services in different ways, and vary in the definition of qualifying diagnoses or conditions. Congress has, however, required state programs to provide and promote family-centered, community-based, coordinated care. A major recent emphasis of Title V programs has been on promoting enrollment of children with special health care needs in managed care plans, monitoring results, and encouraging program and plan adjustments to better serve these children and their families.

Family Payments and Caregiving

Figure 7.1, presented earlier, includes information on the source of insurance coverage for children rather than the source of payment for services. Thus, it does not refer to out-of-pocket payments by families. Little specific information is available on the share of palliative and end-of-life care for children that is paid for by families out-of-pocket, although some hospices can identify the share of their income derived from family or individual payments.

Young families with children often have limited resources—both income and savings—to cover the considerable health care costs generated by a child’s serious illness or injury. Some qualify for Medicaid coverage or other public programs only after they have “spent down” their own financial resources, lost or given up their jobs to care for a child, or otherwise impoverished themselves.

As described in Chapters 4, 5, and 6, families also support their ill or injured children by personally providing much health and supportive care. Although the care provided by a mother, father, or other relative cannot be valued merely in economic terms, a comprehensive analysis of the economic

aspects of child illnesses would include not only out-of-pocket payments but also unpaid care and time lost from caregiver’s paid work.

In addition to initiatives to extend insurance coverage for children, efforts to assist family caregivers through training, respite services, and other support have been growing. Public and private financing of assistance for caregivers is, however, still limited and often offered only to narrowly defined groups, such as families of children with severe developmental disabilities or adults with dementia. A recent review for the American Associated of Retired People of 25 state programs for caregivers concluded that many have such limited budgets that they can serve only a small number of caregivers. The review also concluded that increased funding would help more people seeking to keep a family member at home, but increased flexibility is also needed to fit the diverse circumstances and needs of family caregivers (Coleman, 2000).

Health Care Safety Net

This country’s so-called health care safety net for the uninsured and underinsured has been characterized as “a patchwork of providers, funding, and programs tenuously held together by the power of demonstrated need, community support, and political acumen” (IOM, 2000a, p.17).22 In addition to direct Medicaid and Medicare payments for patient services, the resources for safety-net providers are a variable and often unreliable mixture that includes other local and state government support, patient payments, philanthropy, volunteer services, and federal payments for hospitals caring for a “disproportionate” share of low-income patients.

As defined in a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, the health care safety net consists of “those providers that organize and deliver a significant level of health care and other related services to uninsured, Medicaid, and other vulnerable patients” (IOM, 2000a, p. 3). Core safety-net providers are those that “either by legal mandate or explicitly adopted mission . . . maintain an ‘open door,’ offering access to services for patients regardless of their ability to pay” (p. 3–4).

For many seriously ill children, children’s hospitals, academic medical centers, community hospital emergency departments, and other providers act as an important but precarious safety net. Nonetheless, given its un-

stable financial base, this system cannot promise reliable, continuing, coordinated care to uninsured and underinsured children with life-threatening conditions.

Philanthropy and Volunteer Funding and Services

Philanthropy clearly plays a role in funding some palliative and end-of-life services for children and their families, but no data on the level or trends in such funding are available. Examples of philanthropic support for pediatric palliative care include

-

targeted community events to raise funds for palliative and hospice services for children and families,

-

inclusion of pediatric hospices in United Way campaigns,

-

foundation grants to support pediatric palliative care programs in children’s hospitals,

-

sponsorship of “make-a-wish” and similar programs,

-

grants and fundraising for camp programs that serve sick children or siblings, and

-

organization of community-based and on-line support groups.

Faith communities also support grieving families spiritually and emotionally. In addition, many enlist clergy and volunteers to provide counseling, visiting, transportation, meal delivery, and other services to families with sick children. Some also fund parish nurse and other programs that provide health and supportive services.

Some philanthropic contributions support direct services for individuals. Other funds go to projects intended to improve the quality of such services, for example, through the assessment of community needs or the development of tools for assessing symptoms and the adequacy of symptom management.

Even in countries in which most health services are financed publicly, hospices may out of choice or necessity rely substantially on private philanthropic contributions and volunteer services. For example, in England, most children’s hospice programs were established outside the structure of the National Health Service, although they may receive government payments as well as philanthropic grants and volunteer services.

Clinical Trials

Most clinical trials are designed to test therapies that researchers hope will prevent, cure, or slow the progression of disease or save injured persons from death or disability. Some trials are intended to test therapies that will

prevent or relieve pain, nausea, and other symptoms that arise from illnesses and injuries or their treatment. Trials may involve problems that are not life threatening, but many enroll patients with very serious conditions. Thus, although usually not intentionally, some end-of-life care is financed by research grants and other funds for clinical trials.

Insurance payments for those participating in clinical trials have long been controversial. Some private insurers have agreed to pay for certain trials or for routine care associated with trials, although many today and in the past have undoubtedly paid for such care without knowing it (IOM, 2000d; NCI, 2001b).23 In June of 2000, the President directed that Medicare explicitly authorize payment for routine patient care costs and costs to treat complications associated with participation in clinical trials.24 A recent study found that nearly 90 percent of Blue Cross Blue Shield plans already pay for routine care in clinical trials, and some encourage the creation of clinical trials to test certain therapies (IOM, 2000d). Coverage of investigational drugs is permitted by a few Medicaid plans, but the committee found no comprehensive information on such policies.

HOW PHYSICIANS, HOSPITALS, AND OTHER PROVIDERS ARE PAID

Overview

How insurers pay providers and how much they pay them can significantly affect child and family access to palliative and end-of-life care and

|

23 |

Routine costs have been defined to be those items or services that are “(1) typically provided absent a clinical trial (e.g., conventional care); (2) required solely for provision of the investigational item or service (e.g., administration of a noncovered chemotherapeutic agent), the clinically appropriate monitoring of the effects of the item or service, or the prevention of complications; and (3) needed for reasonable and necessary care arising from the provision of an investigational item or service—in particular, for the diagnosis or treatment of complications” (HCFA/CMS, 2000d). |

|

24 |

The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced in September 2000 that clinical trials with a therapeutic purpose that will qualify automatically include “1. Trials funded by NIH [National Institutes of Health], CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], AHRQ [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality], HCFA, DOD [Department of Defense], and VA [Department of Veterans Affairs]; 2. Trials supported by centers or cooperative groups that are funded by the NIH, CDC, AHRQ, HCFA, DOD and VA; 3. Trials conducted under an investigational new drug application (IND) reviewed by the Food and Drug Administration [FDA]; and 4. Drug trials that are exempt from having an IND under 21 CFR 312.2(b)(1) will be deemed automatically qualified until the qualifying criteria are developed and the certification process is in place” (announcement at www.hcfa.gov/coverage/8d2.htm). Because Medicare covers few children, this program change will have little impact on children and their families unless Medicaid and private payers adopt similar policies. |

also influence the quality of that care. Depending on the specifics, methods and levels of payment can encourage undertreatment, overtreatment, inappropriate transitions between settings of care, and inadequate coordination of care.

The past two decades have seen major changes in the way Medicare pays physicians, hospitals, and other care providers for their services. Many Medicaid and private insurers in the United States have followed Medicare’s lead and changed their payment methods to mirror those of Medicare. Even when other payers have not adopted the same payment methods as Medicare, they may use elements of those methods for analytic and monitoring purposes. Thus, even though Medicare covers few children,25 Medicare payment policies may have significant spillover effects on children and adults covered by Medicaid or private payers. Further, because Medicare is such an important payer, providers may develop perceptions and standard operating procedures based on Medicare policies that they then apply to patients covered by other payers and other payment methods. For these reasons, it is useful to understand Medicare payment policies and methods.

In 1983, Medicare adopted a prospective payment system (PPS) for inpatient hospital care. Under the PPS, Medicare reimburses hospitals a fixed payment per inpatient discharge regardless of length of stay. As explained below, the level of payment for each discharge varies based on the diagnosis-related group (DRG) into which the discharge is classified. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 mandated the adoption of PPSs for other services, including home health care and skilled nursing facility care. Later legislation modified some provisions, but the basic direction of change— toward prospective payment—remains.

The primary goals of prospective payment methods have been to limit the rate of increase in health care costs, increase efficiency in health care, and make cost trends more predictable. In addition, they also may reduce certain kinds of administrative burdens and allow health plans more flexibility. Depending on how providers react, the quality of care could improve (e.g., if unnecessary services are cut) or decrease (e.g., if beneficial services are curbed or patients are discharged before they or their out-of-hospital care providers are ready).

Prospective reimbursement systems can, however, threaten access to care for patients with particularly high-cost needs (i.e., needs for which the cost considerably exceeds the fixed payment for care). As noted above, Huskamp and colleagues (2001) documented reports from multiple loca-

tions of patients with high-cost care needs being denied access to hospice because the cost of the services required would far exceed the hospice per diem payment. Efforts to “risk-adjust” Medicare payments to match patient characteristics continue, but no approach is yet considered satisfactory (MedPAC, 2000a).

The use of separate payment systems by Medicare and other payers for different types of services also creates incentives for shifts in the setting of care that may not be most appropriate for patients. Huskamp and colleagues (2001) documented providers’ reports of transitions between care settings that were attributable to financial incentives in the Medicare fee-for-service program and that negatively affected the quality of care for the dying patient in the view of the provider.