APPENDIX D

CULTURAL DIMENSIONS OF CARE AT LIFE’S END FOR CHILDREN AND THEIR FAMILIES

Barbara A. Koenig, Ph.D.*and Elizabeth (Betty) Davies, Ph.D.†

“Every medical encounter involves the meeting of multiple cultures.”

Linda Barnes, et al., 2000 [1]

“Treatment may be given more as a ritual commitment to the value of fighting death than out of rational expectation that it will help the patients.”

Talcott Parsons, Renee Fox, and Victor Lidz, 1972 [2]

INTRODUCTION

The Relevance of Cultural Difference at Life’s End

End-of-life care and palliative care for children and their families encompass key domains of life that are inevitably shaped by cultural context. Understandings of the boundary between life and death and the rituals that give meaning to this key transition vary widely. Is it critical to fight death or should it be accepted as part of life, beyond the control of medicine? What is the meaning and significance of the loss of an infant or child? How do

parents, the family, and the broader community react to the crisis of life-threatening illness and experience a child’s loss? Finally, how should the American health care system incorporate attention to cultural difference in efforts to reform and improve care for children living with life-threatening and terminal illness and their families? To answer these questions we provide an overview of what is known about the relevance of cultural difference in health care for children and families, specifically focused on end-of-life care and bereavement.

When cultural difference is considered, we generally think of differences among families from varied ethnic backgrounds. “Ethnocultural” background influences all aspects of health care, nowhere more profoundly than when death is near. Even patients and families who appear well integrated into U.S. society may draw heavily on the resources of cultural background (particularly spirituality) when experiencing and responding to death. When cultural gaps between families and health care providers are profound—accentuated by language barriers and varied experience shaped by social class—negotiating the difficult transitions on the path to a child’s death, always a daunting challenge, becomes even more difficult. All domains of end-of-life care are shaped by culture, including the meaning ascribed to illness, the actual language used to discuss sickness and death (including whether death may be openly acknowledged), the symbolic value placed on a child’s life (and death), the lived experience of pain and suffering, the appropriate expression of pain, the styles and background assumptions about family decision making, the correct role for a healer to assume, the care of the body after death, and appropriate expressions of grief. When the patient’s family and health care providers do not share fundamental assumptions and goals the challenges are daunting. Even with excellent and open communication—the foremost goal of culturally appropriate care— barriers remain. Differences in social class and religious background may further accentuate the profound challenge pediatric palliative care presents to the health care system.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and continuing today, the death of a child has been considered a tragedy of the first order in the United States. For the family, few experiences are as difficult to navigate and to survive emotionally, physically, and economically intact. Significant health care resources have been devoted to forestalling premature death in children and newborns, often with great success, such as in the treatment of childhood cancers. The high cost of intensive care for premature newborns may be lamented, but services are rarely questioned or denied. Some might argue that this devotion to forestalling death in childhood is itself a deeply rooted cultural feature of U.S. society, expressed vividly in the priorities of the political and medical care systems.

The question of whether the loss of a child is experienced in a funda-

mentally different way in societies with different values or significantly higher childhood death rates is of more than academic interest [3]. Clearly if a family bears eight children and only expects two to survive to adulthood, the experience of death will not mirror that of a United States middle class family whose only child dies, although feelings of grief and loss will be as deeply felt, albeit differently expressed. In resource-poor environments it may not be possible to devote significant means—emotional or financial— to stave off a child’s death, even one that is theoretically preventable. One might argue that the U.S. focus on child death as a tragedy is in some ways a feature of affluence. Unlike many countries today and unlike most periods of human history, we have the privilege to focus on extending the lives of children with chronic, life-threatening conditions.1 Significantly, immigrants to the United States may have markedly different expectations about child death shaped by the experience of severe poverty, health care systems marked by inequality, and war or other catastrophes.

Thus, a key cultural feature of our efforts to improve the care of dying children in the United States is a profound yet generally unspoken background assumption: we believe that death in childhood is “unnatural” and unthinkable, that morally it should or ought to be controllable. Because death in childhood is an unspeakable tragedy, almost an obscenity, we devote nearly unlimited resources to preventing it. A significant consequence of this cultural stance is that the death of infants and children in the United States health care system takes place only after all aggressive efforts to stave off death have failed. Often, death follows an explicit negotiation about the exact moment, location, and mode of dying. Estimates are that a high percentage of deaths in intensive care units (ICUs) (some studies report close to three-quarters) occur following an explicit negotiation or decision-making process [4, 5]. This makes good communication—the core element of decision making—a high priority. In an increasingly diverse society, the goal of excellent communication about palliative care realities, which is difficult under the best of circumstances, becomes a serious obstacle to care.

When the Institute of Medicine (IOM) conducted its first comprehensive assessment of care of the dying in the United States [6], little was

known about the impact of increasing cultural diversity on the provision of palliative care services or end-of-life care generally. In 1993, Koenig conducted a review published in the IOM report that described the paucity of research findings to date; the review focused on the importance of unexamined Western assumptions undergirding bioethics practices guiding end-of-life care for adults and emphasized the importance of encouraging a sophisticated understanding of the nature of cultural difference, in order to avoid the harmful effects of stereotyping patients [7]. Since that first report a growing literature documenting the role of cultural factors in end-of-life (EOL) care for adult patients has developed (see a recent review by Kagawa-Singer and Blackhall [8]). Although still incomplete, the research to date reveals the dimensions of cultural difference most salient in EOL care, including the focus on autonomous decision making by individual patients, varying preferences about the intensity of treatment, differential hospice use, disparities in access to pain medications, and concerns about trust in the health care system. By contrast, very little research on cultural issues specific to infants and children has been published.

A Firm Research Base Is Lacking in Pediatrics

An extensive review of the health care, psychological, and anthropological literature conducted by one of the authors (Medline 1990–2001, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Anthropological Literature) using a variety of keywords in numerous combinations (including but not limited to children, pediatric, culture, ethnic, death, dying, palliative, hospice, illness) documents the lack of published research in this area. We found approximately 20 articles published over the last 10 years that report empirical findings related to cultural issues in families where a child is seriously ill or dying or has already died. Some of those studies included a discussion of cultural issues in palliative care outside the United States. Although of theoretical interest, studies of other societies—when the cultural background of the patient and family match that of the health care team in a homogeneous society—are less germane to the situation of plural societies like the United States. We conclude that a firm research base on cultural dimensions of end-of-life care for children and families is lacking. In particular, how culture affects negotiation about treatment decisions and palliative care in the American context is little studied.

As with pediatric palliative care more generally, and as documented in the IOM report for which this background paper was prepared [9], the research base supporting practice is limited. However, because children are inevitably part of families, much that has been learned about the cultural dimensions of EOL care for adults may be directly relevant to children, although research specific to the unique needs of children is of course

necessary. Whether the person dying is a newborn or a revered grandparent, serious illness affects the family as a whole, and decision making about end-of-life care is often a shared responsibility, even for adolescent and adult patients.

Furthermore, structural and other constraints on the provision of palliative and EOL care to certain population groups are likely to be shared across age groups, affecting both children and adults. Differences in utilization of hospice services among U.S. populations, for example, are well known. African-Americans—12.3 percent of the U.S. population—comprise only 8 percent of hospice patients [10]. As a group, minority patients account for 25 percent of the population but only 17 percent of those receiving hospice care [11]. Although the exact reasons for these disparities are unknown, it has been suggested that hospice care may present barriers to underserved populations, those without the economic resources to shoulder the burden of family care giving, or those who lack a stable home for the provision of home-based services. Subtler barriers may be created by the hospice philosophy of open acceptance of and discussion of death. Additional research to investigate this possibility is required.

The Significance of Population Diversity and Profound Health Disparities

There are two primary reasons for the current attention to the issue of ethnocultural diversity in health care. One is primarily political—the recognition and growing acceptance of the United States as a multicultural society marked by inequality; the other is demographic—the increasing diversity of the population.

The task of providing culturally appropriate healthcare services is a daunting one. As widespread disparities in U.S. morbidity and mortality rates are documented and links to varied access to health care services are confirmed, attention to “difference” takes on added significance [12]. Eliminating health disparities across the U.S. population is an established national priority [13]. Recently, as one effort to reduce health disparities, the Office of Minority Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) released national standards for “culturally and linguistically appropriate health services” [14]. It is not always clear, however, how these standards can be applied to improving EOL care for children and what barriers exist to their implementation.

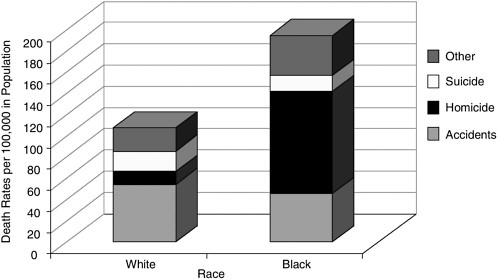

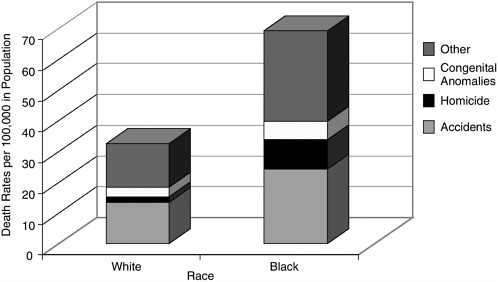

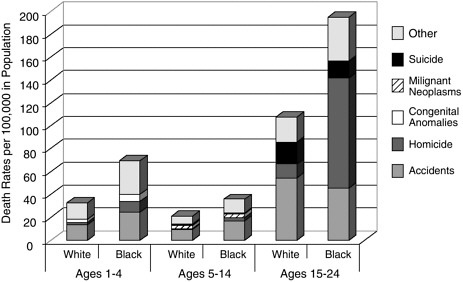

The existence of significant disparities in U.S. mortality rates, for example the continuing excess mortality of African-American males across the life-span [12, 15], complicates the goal of improving EOL care. Figures D.1, D.2, and D.3 compare the rates for leading causes of death in children for African-American males and European Americans at various ages. Differences in cause of death are striking, particularly for violent death and

FIGURE D.1 Death rates for white and black males, ages 1 to 4 (1998).

SOURCE: Table 8 in Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 1998. National Vital Statistics Reports, July 24, 2000, 48(11):1–105.

FIGURE D.2 Death rates for white and black males, ages 15 to 24 (1998)

SOURCE: Table 8 in Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 1998. National Vital Statistics Reports, July 24, 2000, 48(11):1–105.

FIGURE D.3 Death rates by selected causes of death for white and black males, ages 1 to 4, 5 to 14, and 15 to 24 (1998)

SOURCE: Table 8 in Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 1998. National Vital Statistics Reports, July 24, 2000, 48(11):1–105.

accidents. HIV/AIDS does not occur in the “top 10” list for European Americans, while it is included for African-American children from birth through their teens. Excess deaths from preventable causes change the underlying dynamics of care.

Documented health disparities, especially those that reveal higher mortality rates in U.S. populations that have been subject to past racial discrimination, are directly relevant to efforts to improve end-of-life care in the United States, whether for children or adults. Recent studies that reveal differential access to curative services are particularly troubling, such as a lower rate of surgical referral for African-American adults with potentially curable (Stage I and II) lung tumors than for whites [16]. Findings documenting disparities in access to services are less clear-cut in pediatrics. One study found that black children and adolescents with end-stage renal disease were 12 percent less likely to be waitlisted for transplant than whites, even though all were Medicare-eligible [17]. The historical context of lack of access to health care services makes the explicit negotiation of death a particularly charged issue, one likely to be contested [11, 18, 19]. Even if differential access to care and varied treatment outcomes in children prove to be less extensive than those documented in adults, the existence of systematic black/white health disparities will continue to have an impact on the care of infants and children. The prior experience of parental decision makers with their own care, or with the care of other family members, will

inevitably shape their interactions with care providers about a critically ill child. African-Americans may now be seeking treatment for their seriously ill child in a hospital that denied care to blacks within the memory of their parents and grandparents.

The attention of physicians to palliative care needs is also affected by historical patterns of discrimination. Physicians practicing in communities lacking access to care may make life-saving technologies—rather than improving care for the dying—a top priority. Focus groups conducted with African-American physicians (including pediatricians), who often care for high numbers of minority patients, in four regions of the United States found that end-of-life care was simply not a priority [20]. The “Initiative to Improve Palliative Care for African-Americans” is a national effort to focus attention on care near the end of life [21]. Strategies targeted to the needs of particular communities are critical.

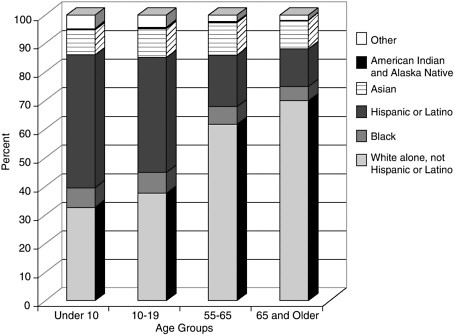

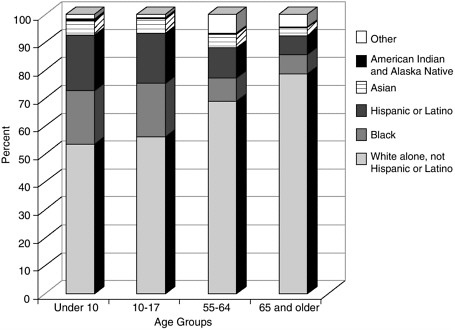

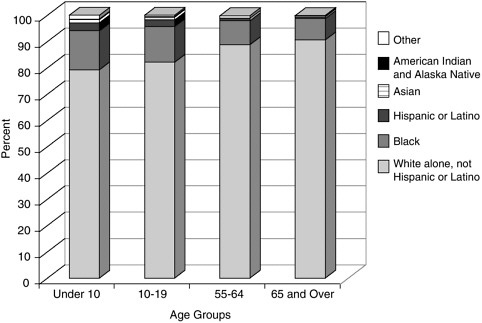

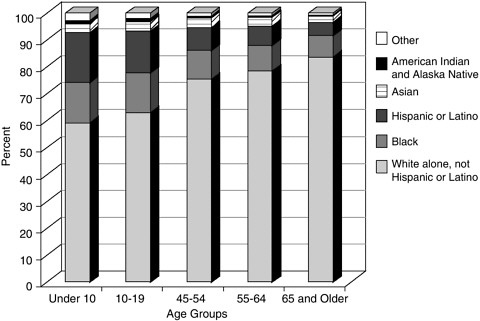

The diversity of the U.S. population has increased markedly over the past decades. Although most pronounced in states like California and New York, the U.S. population as a whole is more diverse today than at any point in the twentieth century. The 2000 census reveals that 20 percent of the U.S. population, or 56 million people, are immigrants or first-generation residents. Projections suggest that some areas of the U.S. will have no “majority” population by the middle of the twenty-first century; people of color will triple by the year 2050. Due to higher birth rates in some communities and greater immigration rates among the young, the diversity in the U.S. population is greater in the youngest age groups. This means that when one considers the arena of end-of-life care, there is far greater diversity in pediatric than in adult practice. Overall, the majority of U.S. deaths occur among individuals greater than 65 years of age, in the eight, ninth, and increasingly the tenth decade of life. Thus, the typical adult hospice or hospital-based palliative care service will have a population of patients that is considerably “whiter” than a clinic focusing on children; attention to cultural diversity is more acutely needed in pediatrics than in the adult practice arena. Figures D.4 through D.7 compare the U.S. population diversity by age group in three states and for the U.S. as a whole (Figure D.7). In California (Figure D.4), only 30 percent of the population under age 10 are identified as white; in New York (Figure D.5), the figure is 50 percent; and in Ohio (Figure D.6), 80 percent.

The increased attention to diversity is also a strong political and moral commitment, not simply a response to “the numbers.” During the early twentieth century, the expectation was that new immigrants would simply melt into the U.S. mainstream. Accepting the health care practices of the dominant society was an explicit element in the “acculturation” process. The fact that certain populations, specifically those set apart by the practices of racism, were excluded from the melting pot was little noticed. Populations do not “melt” with equal rapidity.

Likewise the idea of “acculturation” has proven to be a poor model of the complex process of accommodation and adaptation occurring in the United States. In a truly multicultural society, all parties in the exchange are transformed—it is not simply a matter of immigrants gradually becoming Americanized while stewing in the “melting pot.” In health care for seriously ill children, it is not helpful to consider the absolute level of acculturation of any specific individual or family. Inevitably, families will be varied in their knowledge of and integration into “mainstream” health care practices. A single family may be “multicultural,” including grandparents who are very much involved in caring for a child with a life-limiting condition but who are unable to speak English and lack familiarity with the United States’ health care system. In the same family the child and his or her siblings may have been born and educated in the United States, leaving the parents caught in between the expectations of their American-born children and their desire to meet the demands of grandparents. Members of the same family may draw on the resources of culture differently; they may embrace different religious faiths or engage selectively in cultural practices.

Increased population diversity is a feature of health care professionals and health care workers in general, not just of patients. Many nursing assistants and home health aids, as well as physicians, nurses, and social workers, are themselves immigrants or self-identify as belonging to a particular ethnocultural group. The varied cultural backgrounds of care providers may influence their expectations about what is appropriate care for seriously ill children. Cultural expectations of nursing home personnel caring for the elderly have been show to be of concern when decisions are made to withhold or withdraw treatment, particularly tube feeding, which may have significant symbolic value [22]. Similar concerns may exist in pediatric long-term care settings if care providers come predominantly from cultural or religious backgrounds where feeding is considered obligatory, regardless of benefit to the patient or the desires of the child or family. Potential conflict in negotiations about appropriate end-of-life care comes to the fore in situations of diversity.

DEFINING THE KEY DIMENSIONS OF CULTURAL DIFFERENCE: INTERSECTIONS OF “RACE,” ETHNICITY, SOCIAL CLASS, AND IMMIGRATION STATUS

What Differences Make a Difference?

Considerable research documents the relevance of ethnocultural and religious differences in the experience of death and dying and in clinical approaches to end-of-life care [23, 24]. However, health research in general does a poor job of making clear analytic distinctions among the key ele-

ments of difference. When we talk about “cultural” difference, do we mean a patient or family’s voluntarily adopted and expressed “ethnic identity,” their nation of origin if recent immigrants, their “race” as assigned by a government enforcing discriminatory laws such as segregation, or specific health-related practices such as diet or use of medicinal herbs? In health care research there is considerable confusion in terminology, particularly with regard to the use of the term “race.” In a review of articles making comparisons among human population groups published in Health Services Research, Williams noted, “Terms used for race are seldom defined and race is frequently employed in a routine and uncritical manner to represent ill-defined social and cultural factors” [25]. Lack of precision—näively conflating race, biology, and culture—makes it impossible to tease out the causes of health disparities between racialized2 populations and more privileged groups.

The lack of consistency in the use of terminology for concepts of race, ethnicity, ancestry, and culture is manifest in the wide variance in terms used to identify individual and group identities [27]. Terms such as white, Caucasian, Anglo, and European are routinely used interchangeably to refer to certain groups, whereas black, colored, Negro, and African-American are used to refer to comparison groups [28]. Also, white–black comparisons are straightforward in contrast to the confused use of terms such as Hispanic and Asian. Both of these labels, one based on linguistic criteria and the other on continental origin, lump together many populations of people reflecting enormous variability in factors related to health and medical care.

Extensive debates in the biomedical literature focus on the appropriate use of terms such as race, ethnicity, and culture [29, 30]. Much is “at stake” in how these categories of difference are utilized when conducting research or in designing programs to improve the cultural competence of health care providers. In particular, approaches to conceptualizing disease etiology or health outcomes may have moral significance if one naively assumes that culture predicts behavior in a precise way or that something essential or “inherent” in a certain population leads to poor health outcomes or barri-

|

2 |

The term “racialized” population is preferred by many anthropologists to the use of the term “race.” Because human races are socially constructed categories, and not biological or genetically distinct groups, use of the active term makes it clear that different populations are understood as biologically inferior only within particular social and historical contexts. Within U.S. history, for example, certain populations, such as Jews, the Irish, and immigrants from southern Europe were once considered as separate “races,” but were later de-racialized. These changes are reflected in the categories used by the U.S. census in describing population differences. See reference 26. |

ers to health care access. In the case of black–white differences in infant mortality or homicide rates, for example, how one thinks about causation, and the relative contribution of genes, environment, and social structure, may determine the type of intervention recommended. Meaningful genetic and biological differences do not always map clearly onto social categories of human difference, whether defined as race, ethnicity, or culture. If we talk about “racial” differences about preferences for palliative care services, what exactly do we mean? In the United States efforts to tease apart the independent contributions of “race” and socioeconomic status (SES) when analyzing health care outcomes may be daunting.

Although the dimensions of difference most relevant to EOL care are likely to be social or cultural, biological or genetic variation may also be germane. For example, the field of pharmacogenomics tracks individual and group differences in drug metabolizing enzymes to predict response to medications such as chemotherapy or pain medicines. Although classic understandings of human “races” do not parallel actual genetic variation at the molecular level [31], there may be allele frequency differences among socially defined populations relevant to pharmacogenomics [32, 33]. More sinister applications of genetic reductionism may link excess homicide rates in certain populations to a genetic predisposition to violence. Although this example may seem extreme, it points out the importance of clear thinking about the relative contribution of genetic variation, environment, and social context in thinking about cultural difference in health care. It has been known for decades that there is ethnocultural variation in the expression of pain or painful symptoms [34]; the degree of variation in the actual experience of pain—possibly modulated through the action of pain medicines— remains unexplored.

Immigration status is another key category of cultural difference. Recent immigrants provide challenges to the health care system, particularly in end-of-life care. In much of the world, the American ideal of open disclosure of information about diagnosis and prognosis is not the norm [35, 36]. In fact, patients and families may experience the directness about diagnosis characteristic of U.S. health care as needlessly and aggressively brutal, violating norms espousing “protection” of the ill. Although children may be seen as more in need of protection than adults, much pediatric palliative care literature recommends openness—appropriate to an ill child’s age—as preferable to concealment. U.S. bioethics procedures governing end-of-life care may seem unfathomable to those newly in this country, but it is perhaps the assumptions of bioethics that are culturally bound. As Die Trill and Kovalick note, “Those who argue that children always should be told the truth about having cancer must recognize that the truth is susceptible to many interpretations” [37] (p. 203). Parents or other family members who object to sharing the full differential diagnosis with an ill child

may be accused of being “in denial” about the severity of their child’s illness. Lastly, the experience of those immigrants who are refugees from political violence or war adds another dimension. The effects of multiple losses—on family members, including the death of other children in the family, one’s country, one’s entire history—are difficult to predict but clearly shape a family’s response to the serious illness and threatened loss of a child. Responses may appear to be overly stoic or overly emotional.

In the U.S. context it is especially important to separate analytically the concepts of culture, ethnicity, and race from the effects of SES. Historically underserved populations may have special barriers to EOL care that have little to do with difficulties in communication and are not related to their identification with a certain set of ethnic traditions. In a ground-breaking study, Morrison documented the lack of availability of narcotic analgesics in minority communities such as Harlem; pharmacies simply did not carry the opiates that are “state-of-the-art” drugs for pain control in children as well as adults [38]. The American “drug wars,” including the recent battles about the abuse of time-release opiates like oxycontin, are often fought in poor neighborhoods with limited access to legitimate employment [39]. Children from minority backgrounds may not receive adequate pain control if drugs are not prescribed because of fears of theft or abuse by a child’s family members. When members of the health care team are hesitant to prescribe narcotics it may be a legitimate concern based on factual information about a particular family’s drug history, or it may be the exercise of racial stereotyping. The end result is the same: children may be denied needed pain relief. The experience of children with sickle cell disease, whose pain is often undertreated, is an example [40-42]. Culture thus contributes to inadequate symptom management, but indirectly, through the actions of health care providers. Research in a Los Angeles emergency department documented that Hispanic patients with injuries identical to whites were given less analgesic medication [43].

Strategies: Cultural Competence, Cultural Sensitivity

Within the U.S. health care system, considerable attention has been paid to efforts to improve the “cultural competence” of practitioners, including pediatric care providers [44, 45]. Most recently, national guidelines, including standards for the availability of translation services, have been promulgated [14]. The American Psychological Association has posted guidelines for culturally sensitive end-of-life care on its Web site [46].

In spite of considerable rhetoric, there are no widely accepted definitions of terms such as cultural competence, cultural sensitivity, or culturally appropriate care. We argue below that no one clinician can ever be fully “competent” because it is impossible to learn by memory a full compen-

dium of the world’s cultural practices and beliefs. The language of “competence” also suggests that all dimensions of cultural difference are encapsulated within the bounds of the patient–family–care provider relationship, ignoring social forces that inevitably impinge on the most virtuous clinician. In general, we favor the notion of culturally “sensitive” or “appropriate” care, which focuses on specific skills, such as communication, rather than on mastery of cultural traits. It also fosters the notion of respect for diverse beliefs, and self-reflection about one’s own cultural background [18].

Major efforts in health professional education in end-of-life (EOL) care have paid attention to the cultural dimensions of EOL care. The American Medical Association’s Education for Physicians in EOL Care (EPEC) program and the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) include attention to ethnocultural difference.

A Caution Regarding Use of Language—Ethnocultural Difference

In the discussion that follows, we define culture as the “the conscious and unconscious structures of communal life that frame perceptions, guide decisions, and inform actions. It is the web of meaning in which each person lives” [1]. This interpretive rendering of culture has dominated anthropological theories since formulated by Clifford Geertz [47]. We use the term “ethnocultural” difference to refer to patterns of values, beliefs, and attitudes found among individuals who share a common language and may claim the same ancestry, religion, folk or dietary practices, or general world view. The term “ethnicity,” when correctly used, is similarly defined.3 However within biomedicine the term ethnicity has unfortunately been appropriated as a “politically correct” replacement for race. We use the term ethnocultural to keep our analysis focused on the cultural domain, while at the same time avoiding an “essentialist” view of cultural difference. Suggesting that ethnic culture is an essential feature of individuals or families—rather than a complex, dynamic resource, embraced or abandoned and constantly changing—is dangerous and inaccurate. Much naïve work in cultural competence education seems to suggest that culture predicts behavior in a straightforward way. This approach is inherently reductionistic and risks stereotyping individuals and families.

Furthermore, attributing differences in behavior, attitudes and beliefs to race has the potential to reinforce racist stereotypes. Certainly, some U.S.

populations have been racialized in the past, with groups subject to discrimination based on notions of inherent difference correlated with skin color or national origin. Thus explaining how “race” is relevant to palliative and EOL care is complex; it is most relevant when examining lack of access to services or failure to embrace bioethics practices that demand a fundamental level of trust in the health care system. The term itself must be used cautiously to avoid the implication that inherent, essential differences among human populations exist.

WHAT’S KNOWN; WHAT’S NOT KNOWN

Review of the Research Base on Cultural Dimensions of EOL Care in Adults and Families: Can We Extrapolate?

Progress has been made in understanding the relevance and importance of cultural diversity in end-of-life care for adult patients [8]. The primary clinical implications of that research base are discussed below, with a focus on communication and negotiation about appropriateness of care. Here we ask the following questions: Can we extrapolate from what we know about the cultural dynamics of providing EOL care to adults? Do significant differences exist when the goal is providing culturally sensitive end-of-life care to infants or children with life-limiting conditions and their families?

Negotiations about appropriate care of children unlikely to survive to adulthood are shaped by cultural context. What is the meaning of a child’s death for the child, the family, the broader society? Is it an ultimate tragedy, a life-changing event? Or is it taken for granted, deeply felt, but understood as part of life? Because a child’s dying is “out of order” in most industrial societies, this relatively rare event is managed very differently in pediatrics than in adult medicine or geriatrics.

The epidemiology of death in childhood is also significantly different from that of death in older people. Compared with adults, the causes of death in children are more varied and the pathways to death are less predictable (see Chapter 2, “Patterns of Childhood Death in America”). Accidents are more common, and many deaths are the result of genetic or neurodegenerative illnesses and may follow a prolonged period of disability. A large proportion of pediatric death occurs during infancy. There are more commonalities in the cause of death among adults, with the majority succumbing to the major killers, cardiovascular disease and cancer. In children the picture is considerably more complex, making the tasks of prognostication difficult. Christakis has documented the sociological features of medical practice that lead to physicians’ routine overestimation of patients’ likely survival [48]. In pediatrics, the inherent uncertainty of prognostication is increased by the variability of diagnoses leading to death, contribut-

ing to delays in implementation of palliative care even greater than those with adult patients.

CULTURE MATTERS: KEY DOMAINS OF CLINICAL SALIENCE

A basic principle of pediatric palliative care is providing family-centered care that takes into account both the common and the unique needs of families when a child has a terminal condition and is dying [49]. Despite this emphasis, remarkably little attention has been paid to understanding how a family’s cultural background influences its experience as it faces this most traumatic event. This seems a remarkable oversight, since it is widely recognized that cultural values, beliefs, and practices play a central role in shaping how families raise and care for their children not only when they are healthy, but especially when they are seriously ill [37]. Watching a child fall sick and die is a crisis of meaning for families, and it is through their cultural understandings and practices that families struggle to explain and make sense of this experience [50].

Extrapolating from the growing literature on cultural issues in EOL care for adult patients and families, and gleaning what has been documented in the more limited pediatric literature, it is possible to identify the key domains of clinical significance in caring for children from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds who are unlikely to survive to adulthood. In general, the cultural challenges of EOL care can be divided into two fundamental categories: those that do, and those that do not, violate the health care team’s foundational cultural values, norms that may also be enforced by legal requirements. In the first category are cultural values or practices that call into question the biomedical goal of combating disease and extending life. A family who refused to allow a potentially curative limb amputation for a female child with osteosarcoma because of beliefs about the need to preserve bodily integrity, and a daughter’s marriageability, would immediately create consternation for health care team members. By contrast, another family who wished to engage a spiritual healer to pray for a successful outcome to the same surgery would not create a cultural crisis, since the family’s goals could easily and effortlessly be incorporated into the clinicians’ care plan. Generally, issues such as care of the body after death do not provide a fundamental challenge to biomedical values and beliefs; thus customs prescribing particular approaches to post-death care are relatively easy to implement unless they violate laws governing disposal of the body. However, even in post-death care there may be situations that lead to cultural conflict, such as requests for autopsy or organ donation in situations where the wholeness of the body is highly valued. And the domain of grief counseling and bereavement care may or may not elicit conflict. For pediatric specialists focused on cure, less is “at stake” once a child has died

and can no longer be saved, but conflicts may still emerge over differing definitions of acceptable grieving practices.

Family Roles and Responsibilities in Shared Decision Making

In traditional bioethical decision making about end-of-life care for a competent adult patient, the decisions are left up to the individual; theoretically the family or broader community is not critical to the patient’s choices. In the case of children, where parents become surrogate decision makers, the situation is much more complex [51]. Disagreements about the goals of care, although rare, are emotionally difficult for all. In many cross-cultural situations, the Western view that individual patients (or in the case of a dying child, parents alone, in consultation with their child’s physicians) will make decisions about care may be too narrow. In some societies a social unit beyond the nuclear family may also have considerable decision-making authority. Elders in an extended family or clan group may expect to be involved, and parents may desire this. Integrating them into care in a Western hospital or pediatric unit is hard but may be desirable. Gender may play a role as well. In traditional male-dominated societies, mothers may never have experienced the level of decision-making authority automatically granted to both parents in the United States. This may be a source of tension. Similarly, the evolving practice in pediatrics of requesting “assent” to care by older children, especially girls, may create tensions within the family.

A further dynamic may result from the ideal “shared decision-making” model. Tilden et al. have documented stress among family members involved in decisions to withhold treatment [52]. The impact of parental involvement in decisions to terminate treatment has not been studied extensively. Inexperienced clinicians or trainees may present decisions about limiting painful or aggressive procedures—sometimes an opening to a transition to palliative or hospice care—in an insensitive way, making it appear that the parents or other decision makers must give “permission” for futile care to be withheld. Although the parents’ role in making decisions on behalf of their infant or child must be respected, few parents, regardless of their cultural background, are able to do this easily. In fact, the resistance to giving up hope and explicitly limiting therapies found among families from diverse backgrounds may be appropriate. Models of care that do not require that curative therapies be abandoned in order to obtain excellent palliative services may ultimately lessen this problem. Parents should never be told that care will be withheld; rather the focus should be on meeting the needs of the child and family.

Varied Understandings of the Role of Health Professionals or Healers

Just as the appropriate role of parents caring for a seriously ill child may vary, the families’ expectation of the role played by health professionals may differ. In some societies, healers are expected to make a diagnosis almost magically, perhaps by feeling the pulse without asking any questions. Healers may exert considerable power and authority; they may expect and receive deferential behavior. Patients and families schooled in these traditions may be confused by the shared decision-making ideals of Western practice. They may lose confidence in physicians who do not appear to know unequivocally the correct course of action but instead ask for the parents’ views.

In many societies the roles of healer and religious specialist intersect. “Each religious tradition has its own images and ideals of the doctor, in which the individual engaged in healing is defined as enacting some of the highest ideals of the tradition itself” [1]. The healer’s role at the end of life may be particularly meaningful, or it may be proscribed to take on the care of those not expected to survive, as in the Hippocratic tradition.

Families who have been denied access to health care providers may also question the trustworthiness of the “establishment” health system, worried that those in power do not have their best interests at heart. The disparities in morbidity and mortality across U.S. populations suggest that often African-American patients receive less intensive care. The irony is that research on end-of-life decision making in adults reveals that minority patients may actually desire more aggressive care near the end of life [53].

Communication Barriers, Need for Translation

Negotiation about the appropriateness of clinical services for children nearing the end-of-life is a complex task when health care professionals and family members share fundamental goals and assumptions. By no means has a successful “formula” for such communication been established. When cultural barriers exist, particularly those created by language, the goal of open and effective communication is exceptionally difficult. Language translators may be available only intermittently, and are often poorly trained. In March 2002, two hospitals in Brooklyn, New York, that routinely serve large numbers of Spanish-speaking patients were sued for failure to provide

translation services, examples of a number of such legal actions dating back several decades.4

The task of language translation in the arena of ethical decision making and end-of-life care is particularly complex. How does one translate a discussion about a “do not resuscitate” decision to a family with no previous experience of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and no prior knowledge of the American bioethics tradition of requiring permission not to offer CPR, even to an infant or child actively dying? What if the language characters representing resuscitation are interchangeable with those suggesting the religious concept of resurrection? Although it sounds silly from the perspective of Western, scientific understandings of death, who would not elect to have their dying child brought back to life if offered the choice

in those words? How might medical interventions at the moment of death be understood among practitioners of Buddhism who believe that rituals spoken during the dying process guide the “soul” through dangerous spiritual territory and ultimately determine where and how a person will be reborn? How do you negotiate with a family about the location of death— home versus hospital—against a cultural background where speaking of an individual’s death is thought to bring it about or where certain illnesses cannot be named? The use of family members as interpreters—which may be unavoidable—may make discussions such as these even more problematic. Family members may see their primary role as protecting others in the family from harm and thus “shield” them from information viewed as harmful [54].

Furthermore, models of professional translation, such as those employed in courtrooms where relationships are fundamentally adversarial rather than collaborative, assume that language interpreters should function as neutral “machines.” Health care providers need to be aware that translation services such as those available by phone from AT&T may be based on legal models of interpretation. This stance ignores the interpreter’s potential value in providing information about the family’s cultural background, as well as providing language interpretation. When interpreters are engaged as full partners in providing care, they may aid in negotiations about difficult end-of-life dilemmas [55, 56]. When included as part of the health care team—for example, in programs where native speakers of commonly encountered languages are employed as bilingual medical assistants— interpreters can also serve the useful function of explaining the culture of biomedicine to families.

Integration of Alternative and Complementary Medicine into Palliative Care

Parents and other family members may be subject to strong pressures to utilize “ethnomedical” practices and procedures believed to be efficacious. Recent immigrants may utilize products obtained abroad. Practices vary widely, including acupuncture for pain, cupping or coining, dietary prohibitions based on “hot–cold” belief systems, Chinese herbal products, Ayurvedic patent medicines, and full-blown rituals including chanting and the sacrifice of animals. A skilled practitioner creates an open environment in which the child, family, and perhaps a ritual specialist from the community may openly discuss the appropriate blending of biomedically sanctioned medicines and procedures with ethno-medical products. Although some patent medicines and food supplements are known to be harmful and may actually contain potent pharmaceuticals, the health care team is unlikely to obtain a full accounting of all treatments used for a particular child

unless a nonjudgmental attitude is maintained. This may be a challenge when a health care provider must compromise his or her own “ideal” care.

The need to integrate alternative and complementary medicine into palliative care is not limited to patients from particular ethnocultural communities. Research documents that a large percentage of Americans have utilized “alternative” medicine in the recent past [57], with prayer being the most widely utilized practice (82 percent of Americans believe in the healing power of personal prayer) [1].

The Meaning of Pain and Suffering for the Child and Family

Palliative care has as a primary goal the relief of pain and suffering. Ethnocultural difference is relevant to pain management in multiple ways. The effectiveness of symptom management may be lessened by economic barriers to medicines or special treatments. Physicians may undertreat patients because of fear that drugs may be “diverted.” Cross-cultural research with adult patients has documented differences in the way people experience and express pain. It is likely that the appropriate expression of pain by adults in a family will influence what is considered acceptable for children: Is stoicism rewarded? Are there gender differences in outward discussion of painful symptoms? Spirituality may have an impact on the meaning of suffering and hence on the management of symptoms. A study of infants and children with a rare genetic disease (recombinant 8 syndrome) in long-time Spanish-speaking residents of the American Southwest revealed the complexity of suffering. The experience of affected children in these devout Catholic families was thought to mirror Christ’s suffering, providing meaning to an otherwise unexplainable tragedy [58].

Defining the Boundary of Life and Death

Biomedical definitions of death, including the concept of brain death, appear to be clear cut. However, when examined closely considerable ambiguity remains, particularly in pediatrics [59]. Even among biomedical professionals one frequently hears confusion in language when speaking, say, about an organ donor who is technically brain dead, but may appear to be as “alive” as adjacent patients in an ICU. Linguistically, these brain-dead bodies experience a second “death” once organs are retrieved for transplantation and ventilatory support is removed [60]. It is thus not surprising that patients and families can also become quite confused about states resembling death, including brain death, the persistent vegetative state, or coma. Societies such as Japan, which utilize the same biomedical technologies as in the U.S., have not readily accepted the concept of brain death, in spite of the demands of transplant programs for organs [60].

Disputes arise when a child meets the biomedical criteria for “brain death,” but the family refuses to allow withdrawal of “life” support. In a masterful essay, Fins describes two clinical negotiations about withdrawing life support from children defined as brain dead [61]. In one case, the hospital team engages the family’s orthodox rabbi and other religious authorities in a complex series of negotiations, respecting throughout the family’s view that the patient is not truly dead and that only God can declare death. A more contentious case involves an African-American family who maintains a stance of mistrust toward the health care establishment in spite of every effort on the part of the clinical team. The family’s past experience shaped its understanding of the team’s intentions in spite of great effort to gain their trust. Disputes such as these are the “hard” cases, revealing cultural clashes that cannot be ameliorated simply by motivated clinicians, sensitivity, or excellent communication skills, although clearly those things may keep conflict to a minimum or may keep small cultural disputes from erupting into major pitched battles.

Since the causes of pediatric death are much more varied than those in adult medicine, the need for autopsy to determine an exact cause of death may be more important. In the case of rare genetic disease, autopsies may help establish a diagnosis or benefit a future child. The acceptability of autopsy, or other uses of the body following death, is deeply sensitive to cultural and religious prohibitions [62]. Knowledge about the acceptability of autopsy, or requests for organ donation in the case of acute trauma, cannot usually be guessed by “reading” a family’s background.

Furthermore, different ethnocultural groups may have varied understandings of the nature, meaning, and importance of cognitive impairment in a child. In a society where social relationships are a core value, esteemed more highly than individual achievement, disabilities that affect intellectual functioning but do not interfere with the infant’s or child’s role in the family may be more readily “accepted.”

Acceptance of Hospice Philosophy

As mentioned above, utilization of hospice care programs is not identical across racialized U.S. populations. African-Americans (primarily adults) utilize hospice services at a lower rate than do European Americans. There are significant barriers to hospice care for children in general, since many hospices take children only rarely, and few have dedicated programs for children [9]. Thus, the barriers to care for children from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds are likely to be even higher.

Home death is often considered an ideal within the hospice philosophy. A “good death” is often characterized as one that takes place at home, surrounded by family and/or friends, with pain and symptoms under con-

trol, spiritual needs identified and met, and following appropriate goodbyes. Traditionally, this ideal good death required giving up curative interventions. At the moment in U.S. history—the 1970s—when hospice care became a viable alternative, aggressive end-of-life interventions were commonplace, and efforts to secure patient participation in decision making were not yet fully realized. Thus, the home became a refuge from the ravages of hospital death. Even though the strict implementation of a six-month prognosis requirement for hospice is changing, it remains more difficult in pediatrics to predict the terminal or near-terminal phase of illness. Acknowledging that death is near may be particularly difficult. Home death may not be valued in ethnocultural groups where it is considered inappropriate, dangerous, or polluting to be around the dead. Among traditional Navajo, the dying were removed from the hogan dwelling through a special door to a separate shed-like room to avoid the catastrophe of a death occurring in the hogan, which would then have to be destroyed. Burial practices were organized to make certain that ghosts could not find their way back to the hogan, and family members did not touch the dead body. This task was relegated to outsiders. These issues remain salient for those practicing in the Indian Health Service [63]. In some Chinese immigrant communities a death at home may affect the value of a particular property on resale [64].

Care of Family After Death; Bereavement Needs

When a child dies, supportive services to aid a grieving family are vitally important and should be covered by institutional protocols and procedures intended to establish accountability for the consistent provision of such services [9]. The cultural background of the family may be particularly salient in planning for and providing bereavement care. Some authors [65] have specifically addressed family bereavement following a child’s death, but most research includes primarily European-American families. Most researchers recommend extending the work to include families of other cultures, but very little work has focused on cultural issues and family bereavement when a child has died.

Although findings specific to children in the setting of a multicultural U.S. society are lacking, much is known about culture and bereavement more generally. Cultural heritage helps define how individuals and families react to loss, and provides insight into behavior, the expression of emotion, and understandings of death. Cultural approaches to dealing with loss may be more or less standardized but almost always involve a core of understandings, spiritual beliefs, rituals, expectations, and etiquette. In many cultures, different kinds of deaths are understood differently and dealt with differently. The meaning of death and the rituals called for, the emotions

felt, the extent to which others are involved, and how the body is to be disposed of—all may vary depending on such factors as whether the death is a suicide, a drowning, the result of illness, the death of a child, or the death of an elder [66]. Among the Bariba in Africa, certain infants are defined as witches and thus mothers may not be allowed to express grief on their death [67]. Thus, even if one knows something about how a “typical” death is handled in a particular society, one may not be prepared to understand what is going on when a child dies.

In most cultures, it is believed that children should not die before their parents, even though infant mortality may be high. Common sayings attest to this belief. In China, for example, it is said that “black hair should not precede the white hair.” A Korean maxim states that if your parents die, you bury them underground; if a spouse dies, they are also buried underground; but when your child dies, you bury the child in your heart. In Western countries, it is often said that when a person’s parents die, one loses the past, but when one’s child dies, the parents lose their future. The death of a child represents a unique loss. Nonetheless there may be distinctions made based on age, sex, or disability. In many societies a newborn is not afforded the full status of “personhood” until a specified period of time has passed, often 30 days, after which the child is “named” and becomes part of the tribe or group. Bodies of infants who die prior to that period may not be provided with full funerary rites.

In the anthropological literature, significantly more attention has been focused on the rituals surrounding death and the disposal of the body than on the management of death and the dying process [68]. Behaviors and rituals surrounding a child’s dying may be understood in the context of beliefs about the transition of dying, a fundamental “rite of passage.” Many cultures view death as a transition, often described as involving a journey to some other place or state [69]. In many cases, people understand that the deceased will continue to have an impact on the living and continue to communicate with the living. Rituals around dying therefore may have special significance. From a Korean perspective, for example, a dying person should not be left alone, for to die alone means a lonely journey after death to a new life. For Korean families, therefore, it is particularly important that all efforts should be made to enable family members to be with their child at the time of death.

Rituals can be understood as “defining” events: they define the death, the cause of death, the dead person, the bereaved, the relationships between the bereaved and others, the meaning of life, and societal values [69]. Rituals can help to restore a sense of balance to life; they help to strengthen the bonds that connect family members to others in their community. In many societies, death rituals are often extended over considerably more time than is common in American society. They may require isolation of the

bereaved, the wearing of special mourning clothing or special markings, and even actions that seem unpleasant to outsiders, such as tearing at one’s own clothing or hair. Westerners who are accustomed to a single funeral ceremony may fail to appreciate the religious, social, and personal significance of such events. Moreover, families from such societies who reside in the Western world may find themselves unsupported during their bereavement, particularly within health care institutions.

If grieving involves engaging in certain rituals and being able to think, feel, and do certain things in a social environment that supports those endeavors, being in an alien social environment can be very difficult for the bereaved. Grief is not an individual response, but a social one. Moreover, proper grieving may require things as well as people, and those things may not be available when one is away from one’s home community. In addition, when one is living far from home, a death can set off grief for deaths that occurred at the time the person left his homeland, for the home left behind, for a lost way of life, or for other things related to leaving [69]. Consequently, such individuals may feel overwhelmed by the totality of their losses that have been triggered by the death of their child.

In some cultures, the outward expression of feelings is not always recommended or socially appropriate. One study compared and contrasted the experiences of Korean, Taiwanese, and American families whose child had died from cancer [70]. In Korea, external expression of grief when one’s parents die is expected and almost demanded, whereas when a child dies, the expression of grief by crying is more complicated. Internal grief may be more common. Parents may not wish to burden others and especially do not want to add to the burden of their surviving children; therefore, they cry alone or may smile artificially when they wish to cry. However, Korean parents were like Chinese and American parents in wanting to have a certain period of time to externalize their grief feelings, and in appreciating private space and time to do so. Similarities in grief responses were reported in a second study that explored the experiences of bereaved mothers following a child’s death from cancer in Canada, Norway, England, Greece, Hong Kong, and the United States [71].

Somatic expression of emotional distress and grief is also reported in a study by Caspi et al., who conducted interviews with 161 Cambodian refugees living in America. An extraordinarily high percentage of these families (43 percent) had experienced the death of one or more children in the previous 10 years, a result of having lived in a war-torn country before emigrating to the United States [72]. While objective measures showed physical and daily functioning to be unaffected by having lost a child, the bereaved parents strongly believed that they were limited in their ability to do simple physical activities like climbing a flight of stairs or going for a short walk. They also felt that they had difficulty accomplishing chores

such as doing laundry or going shopping. Bereaved parents were far more likely to be experiencing somatic symptoms such as poor vision, pain, and numbness, as well as culturally defined symptoms such as bebachet—translated by the authors as a deep worrying sadness. However, they did not experience more symptoms of psychological depression than the nonbereaved parents.

Similar patterns may exist amongst Mexican families as well, although findings are sparse. Using ethnographic methods, Fabrega described how families respond to the unexpected death of a child in rural Mexico [73]. He found that behavioral and psychological expressions of grief were very common in bereaved mothers, and were understood by the family and the community as manifestations of acute somatic illness. Help was sought from a traditional healer who treated the mother with medicinal herbs and restorative teas.

The question of meaning, and specifically the influence of culture on how families understand the illness and death of their child, has not been adequately addressed in the research literature. However, isolated findings speak to the importance of how families understand the cause of their child’s death and the significant role of culture in shaping these explanatory models. Miller, the author of a popular book on culture and bereavement following the death of a child, indicates that parents of all cultures struggle with finding the answer to two questions following a child’s death: “Why did my child die?” and “Why has this happened to me”[74]? The answers to these questions, however, may vary markedly across the world. In Brazil, Bali, Sulawesi, West Africa, and India, the answers have one thing in common: they each turn attention from the ones who are grieving to the child who has departed. In these places, parents are asking for information about the child’s fate, his destiny, his time, his choice. In other cultures, particularly in the Western world, parents are more often wondering what went wrong and, in many cases, what they did wrong. Guilt seems to be characteristic of all cultures but is more prevalent in some societies. In some cultures, for example, the mother is seen as being most responsible for children, so that when a child becomes ill and dies, the mother reexamines all her behaviors to find the cause of death. Such mothers carry a heavy load of guilt.

Clinical interventions to aid the bereaved must take into account cultural differences. It is critical to acknowledge that Western ways of grieving and disposing of the body are not universally accepted as the “right” way. It is also likely that our theories of grief and mourning, including definitions of “normal,” are inappropriately based on Western behavioral norms. For example, a standard way in the West of dealing with grief is to talk—about one’s experience, one’s relationship with the deceased, one’s feelings. But in some cultures, talking may disrupt hard-earned efforts to feel what is ap-

propriate, and to disrupt those efforts may jeopardize one’s health or safety. In some cultures, talk is acceptable, but one must never mention the name of the deceased person. In other cultures, talk is acceptable as long as it doesn’t focus on oneself. Even in the West, however, not everyone is open to talking. It is important not to label those who do not openly express their emotions as “pathological”[75]. In fact, the concept of pathological grief is primarily a Western construction. A mother in the slums of Cairo, Egypt, locked for seven years in the depths of a deep depression over the death of a child is not behaving pathologically by the standards of her community [76]. There is enormous variation in what is considered appropriate behavior following death. The ideal among traditional Navajo is to express no emotion, while in tribal societies a death may be met with wild outpourings of grief, including self-mutilation [77]. Even in certain Mediterranean societies, widowhood was considered a permanent state of mourning, and mourning clothes were worn for years, if not decades. In a compelling book, titled Consuming Grief, Conklin describes how native Amazonians assuaged their grief by consuming the body of their dead affinal5 kin [78].

Marked generational differences in dealing with death are common. Typically, the older generation seems to be more observant of the traditional rituals, perhaps especially true in immigrant communities. It is important for outsiders who want to help to be sensitive to the possibility of different needs, expectations, standards, and practices in different generations. Moreover, if one’s informant about a particular culture is a younger person, the information that is given may not accurately represent an older person’s experience.

Expertise in dealing with someone from another society is qualified by the limits of one’s experience and knowledge. Even if one has dealt with bereaved people from a given small-scale society, one cannot presume that one’s experience will help in understanding the next bereaved person from that society. Moreover, many people in any one country or society may function within a mix of cultural traditions. Therefore, it may be most helpful to assume that whatever grieving families do has meaning and value to them and then to try to understand it as they do. The task of the outsider who wants to help is to understand the cultural realities of the bereaved, not to fit what they do into a framework that makes sense in terms of the outsider’s culture. Much remains to be learned from the bereaved themselves.

IT’S NOT JUST THE PATIENT AND FAMILY WHO “HAVE CULTURE”

Cultural Aspects of Biomedical Practice in Pediatrics

The lack of pediatric palliative care services in the United States is itself a telling cultural statement. One might ask why the United Kingdom has 23 hospices dedicated to providing services to children with life-threatening illness—more than the entire United States [10]. It is not an accident that hospice and palliative care did not originate in the United States. The shape of our current health care system—which privileges research over care and curative efforts over palliation—reflects firmly established national priorities. Making this observation is not an indictment, rather it is an acknowledgment of the profound paradox embedded in our health care system. Our technological successes carry the seeds of our failures. Indeed, our values have led to the development of cures for many pediatric ailments and an increase in the number of children living with serious chronic illness. Paradoxically, the high value placed on children and their care, and the fact that child death is viewed as a particularly profound tragedy, provide the cultural roots of our current lack of palliative care services for children. Biomedical practices express the cultural assumptions of the wider society, in this case supported as well by political and economic forces. Short, episodic illness is well covered by health insurance. But even relatively well-off middle-class families may experience serious economic consequences when a child is ill and dies over a long period of time. One study estimated an average of $140 per week in uncompensated “indirect” costs associated with care [10].

Unexamined cultural assumptions are apparent throughout biomedicine. Even within the subspecialty of pediatrics a single, monolithic culture does not exist. There are significant differences within subspecialties and between professions. Research has revealed that practitioners interpret the exact prognosis of patients with life-threatening illness quite differently. Even diseases that technically have identically poor prognoses may not be considered equally “terminal” [48]. For example, do-not-resuscitate orders are written more commonly for some diseases and conditions, in spite of similar outcomes [79].

Significant differences exist between professions as well, particularly between physicians and nurses, who often view their roles and responsibilities in end-of-life care quite differently. Muller and Koenig found that understanding a patient’s status as “terminally ill” was much more salient to the fundamental tasks of nursing than for internal medicine, where the work of diagnosis dominated other activities, often to the exclusion of considering whether a patient’s disease trajectory included death in the

foreseeable future [80]. (An exception was extremely time-limited trajectories, clearly revealed by physiological deterioration or imminent dying. In those situations the patient’s terminal condition was the preeminent consideration.) Anspach has demonstrated how physicians and nurses practicing in neonatal intensive care, a site of many infant deaths, have diverse understandings of their patients’ prognoses [81]. She attributes these different assessments to the varied interactions with patients associated with the roles of nurse or physician. Based on situated knowledge, each professional group “reads” the data about an infant’s likely outcome differently. These differing assessments complicate efforts to communicate with family members and negotiate withdrawal and withholding of life-extending technologies [4]. Family members may realistically complain they are hearing a different story depending on whom they talk to on a given day.

Recognizing Cultural Differences That Are Easy to Respect in Practice Versus Those That Offer Fundamental Challenges to Pediatric Palliative Care Providers

Respecting cultural difference may offer a profound challenge to health care practitioners’ most fundamental values. In perhaps the best “text” explaining the cultural dynamics underlying the treatment of a critically ill child, Anne Fadiman, in The Sprit Catches You and You Fall Down, offers a detailed account of how the physicians caring for a young Hmong child with life-threatening, difficult-to-control epilepsy ultimately fail her because of their desire to offer her “state-of-the-art” care identical to that offered to any of their other patients [82]. Through her detailed ethnographic account, Fadiman reveals how in this case the physician’s quest for the “perfect” treatment was the proverbial “enemy of the good.” The parents of the child, Lia Lee, were refugees from the American war in South-east Asia, illiterate in their own language, with ideas about the cause of epilepsy and its appropriate treatment that were completely at odds with the views of the Western health care team. They were not, however, the only participants in the exchange shaped by cultural background and context. Fadiman’s work documents the culture of biomedicine, explaining with great clarity how the physicians’ uncompromising dedication to perfection kept them from negotiating a treatment regimen acceptable to all.

The Need for Clinical Compromise in Order to Improve Outcomes and Care

Often in cross-cultural settings it is imperative to learn to compromise one’s own clinical goals in order to meet the patient “halfway.” Fadiman’s book recounts the profound miscommunication between the pediatricians

and family physicians involved in Lia’s care, the Lee family, and the broader Hmong community. When her parents are unable to carry out a complex regimen of antiepilepsy drugs, the child is turned over to the state’s child protective services agency, provoking a profound and deepening spiral of tragedies. In the end, the physicians wish they had compromised their goals and prescribed a more simple medication schedule. Ironically, the parents’ observation that the medicines were making Lia sick proved true in that one of the antiepileptic drugs contributed to an episode of profound sepsis that resulted in Lia’s persistent vegetative state. A number of American medical schools assign this book as a required text in cultural sensitivity training. Its brilliance lies in revealing both sides of a complex equation: a Hmong enclave transported to semirural California and a group of elite, Western-trained physicians and health care practitioners caught up in a drama they cannot understand, not because the Lee family’s cultural practices are so esoteric, but because they fail to recognize how their own cultural assumptions and deeply held values limit their ability to help the ill child.

The Culture of Biomedicine and Biomedical Death Reflect Features of U.S. Society

National efforts to improve end-of-life care for both children and adults often include the notion that “cultural change” or promotion of “cultural readiness” is essential for reform efforts to be successful [83, 84]. Yet, what this cultural change would look like and what barriers to such change exist are rarely itemized. National public awareness campaigns such as “Last Acts” have used a variety of strategies to change the “culture of dying” in America, including working with the media. For example, one strategy has been to sponsor script-writing conferences to encourage widely viewed television programs, such as “ER,” to include realistic stories about patients near the end of life. In fact, a recent episode focused on end-stage cystic fibrosis. Narratives created for television might convey the idea that a comfortable, pain-free death is possible and should be “demanded” by patients and families as an essential feature of a comprehensive health care system. The stories might convey the important lesson that physicians and other caregivers may forgo their most aggressive efforts at cure without abandoning patients. Unfortunately, these efforts at change ignore a fundamental and problematic social fact—a profound cultural resistance to giving up hope for recovery, a problem in EOL care generally that is most pronounced when a family must negotiate the details of a child’s dying while simultaneously mourning the loss of that child’s future. Difficult for all families and for patients of all ages, this negotiation is particularly troubling if the family has no idea of the cultural “script” being followed by health care providers.

Research by Koenig and her team revealed that adult patients from minority backgrounds, in particular recent immigrants, seemed to lack a sense of the narrative structure of EOL care that English-speaking, middleclass European-American families understood more readily. In particular, the idea that patients and families would make an explicit choice to abandon curative therapy, followed by the “limiting” of aggressive interventions like intensive care and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, did not seem to be a story patients understood. Recent Chinese immigrant patients could not answer questions that presupposed a transition from curative to palliative goals; it was simply beyond their experience [85]. In their experience, doctors do not “stop” treating patients. Efforts to change the culture through engagements with the media—encouraging op-ed pieces in newspapers, script-writing workshops, and so forth—may educate potential patients about existing approaches in palliative and hospice care. Of course, efforts to target media serving different communities speaking different languages would be critical.

However, one cultural barrier is difficult to surmount. Before physicians can recommend palliative care and before patients and families agree to it, in our current system one must first accept the possibility that death is imminent or at least that one’s likely survival is seriously limited. Eventually, current reform efforts—most prominent in pediatrics—to introduce palliative care early in a trajectory of disease or illness may decrease the need for patients or families to embrace a clear transition between curative and palliative modalities of treatment. But it is unlikely that the tension caused by the need to balance conflicting goals will ever dissipate totally.

Thus, even if one embraces the narrative of limiting aggressive treatment and adopting comfort care, including attention to spiritual and interpersonal goals, as a good idea “in principle” for children facing death, there still exists the radically difficult and jarring transition itself, the need to imagine your child, your family, as now taking center stage in a particular EOL narrative. It is no longer theoretical but real. The resistance to seeing oneself, and particularly one’s child, in this role is considerable and may prove insurmountable for many. A set of powerful cultural narratives operates to feed this resistance and encourage its perpetuation. Consider, as one example, the heroic narratives of successful research and triumphant cure that are much more often portrayed by the media than stories of failed therapy and excellent end-of-life care [86]. The content of public relations materials produced by medical centers and ads published by drug companies convey powerful cultural metaphors that are directly counter to the mundane realities of palliative care, often focused on managing symptoms such as constipation. Hospital ads suggest that it is vital to “keep shopping” and eventually you will find the program offering the experimental or innovative therapy that will cure your child. The heroic search for cure is

celebrated in media accounts such as the film Lorenzo’s Oil or a recent New York Times Magazine profile of a family seeking gene therapy to cure their child’s severe, life-limiting genetic illness (Canavan disease) [87]. A full analysis of the culture of dying in the United States must acknowledge these powerful counterimages.