Immunization Issues in Texas

Immunization is a subject of renewed concern in Texas because the state currently has the nation’s lowest immunization coverage rate for 2-year-olds. As reported at the workshop, the Texas Immunization Survey put the coverage rate for the 4:3:1 immunization series1 at 70 percent in 2000. The latest data from NIS (for 2000) indicate that only 64 percent of Texas 2-year-olds are fully immunized with the 4:3:1:3 series, whereas the national average is 74 percent (see Table 2 and www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage/default.htm). Rates vary across the state, ranging from 68 percent in Dallas County to only 59 percent in Houston, according to NIS data. Throughout the state, coverage rates have declined since 1998.

The immunization rates for older adults (ages 65 and over) are more encouraging but still fall short of the national public health goal of 90 percent. For 1999, 70 percent of older adults in Texas reported that they had received a vaccination against influenza in the previous year, compared with a 67 percent rate nationally, and 56 percent reported that they had ever received a vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia, compared with a 54 percent rate nationally (CDC, 2001).

TABLE 2 Estimated Vaccination Coverage for the 4:3:1:3a Series Among Children Ages 19 to 35 Months, 1996–2000

|

|

Percent |

||||

|

Area |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

United States |

76 |

76 |

79 |

77 |

74 |

|

Texas |

72 |

74 |

74 |

71 |

64 |

|

Bexar County (San Antonio) |

74 |

79 |

79 |

72 |

66 |

|

Dallas County |

71 |

74 |

71 |

71 |

68 |

|

El Paso County |

62 |

65 |

78 |

68 |

66 |

|

City of Houston |

68 |

64 |

61 |

61 |

59 |

|

Rest of state |

—b |

— |

77 |

73 |

63 |

|

aFour or more doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and whole-cell pertussis vaccine, three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine, one or more doses of any measles-containing vaccine, and three or more doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. b— = not available. SOURCES: CDC (1997, 1998), Herrera et al. (2000), and CDC, National Immunization Survey (www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage/default.htm). |

|||||

Through several presentations, the workshop examined various aspects of the financing and delivery of immunization services in Texas.

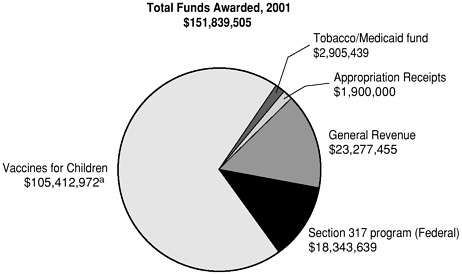

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

Sharilyn Stanley, associate commissioner for disease control and prevention at the Texas Department of Health, reviewed trends in public funding for immunization activities in Texas and some of the challenges facing the state. For 2001, the immunization program budget amounted to $151.8 million (Figure 2). Federal funds make up 76 percent of this amount (VFC funds make up 53 percent and Section 317 program funds make up 23 percent). State funds from general revenue and other sources account for the remaining 24 percent. During the previous 2 years, the program received small amounts of funding from the state’s tobacco settlement.

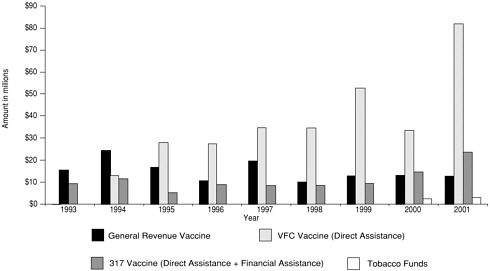

Of the total, $121.1 million was for vaccine purchase and distribution and $30.7 million was for infrastructure activities. Steady increases in funding for vaccine purchase have occurred since 1993 (Figure 3). The total declined slightly for 2000 because of the withdrawal of the rotavirus vaccine. The newly required pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, however, added $30 million in vaccine purchase costs for the state. State funds are used to purchase vaccines for adults and for children not eligible for VFC

FIGURE 2 Amount and source of funds for the Texas Immunization Program, 2001. Federal funds from the Section 317 program and VFC are for the calendar year. State funds (general revenue and tobacco and other funds) are for the state fiscal year.

aVFC Vaccine (DA) is awarded in multiple installments during the year. The fourth installment was received in November 2001.

SOURCE: Sharilyn Stanley, Texas Department of Health, IOM workshop presentation, 2001.

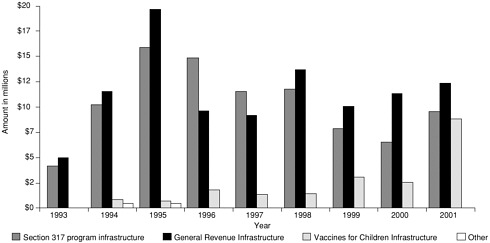

plus special-use vaccines such as the rabies and meningococcal vaccines. Funding for the immunization infrastructure peaked in 1995, followed by decreases in both federal and state funding (Figure 4). At present, state general revenue is the largest single source of funding for the immunization infrastructure. VFC contributes relatively little to support for the immunization infrastructure, but for 2001 the state received a one-time VFC award of $4.25 million to upgrade the pharmacy inventory control system to help manage vaccine ordering and distribution practices.

In the face of the declining immunization rates for 2-year-olds, Dr. Stanley described the challenges facing the state. She noted that the Texas Immunization Survey, which offers more detailed information than the NIS, shows improving coverage rates for children 3 to 6 months of age but declines in the coverage rates for older children. Immunization rates appear to be improving for African-American children and children enrolled in the Medicaid program but are declining for WIC participants. Evidence of a lag in immunization for Hispanic children is a concern because they account for a growing proportion of the state’s large annual

FIGURE 3 Amount and source of funding for vaccines, Texas Department of Health, 1993–2001. Federal funds from the Section 317 program and VFC are for the calendar year. State funds (general revenue and tobacco funds) are for the state fiscal year.

SOURCE: Sharilyn Stanley, Texas Department of Health, IOM workshop presentation, 2001.

FIGURE 4 Amount and source of funding for immunization infrastructure, Texas Department of Health, 1993–2001. Federal funds from the Section 317 program and VFC are for the calendar year. State funds (general revenue and tobacco funds) are for the state fiscal year.

SOURCE: Sharilyn Stanley, Texas Department of Health, IOM workshop presentation, 2001.

birth cohort. In 1998, about 44 percent of the 342,200 children born in Texas were Hispanic.

The state’s increasing birth rate combined with requirements for more expensive vaccines creates a challenge for the state’s budget for vaccine purchase. After the addition of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the immunization schedule in 2000, for example, no supplemental state funds were made available to the immunization program for 2000 or 2001, despite the state’s obligation to provide the vaccine to certain children. The demand for state-purchased vaccines is also coming from children who are not eligible for VFC but who are referred to public clinics by private providers. Dr. Stanley noted that the size of the state’s population and vast geography add to the cost and complexity of distributing and tracking vaccines and monitoring immunization coverage.

Under an immunization improvement plan adopted in May 2000, the state health department will work to improve community involvement in immunization efforts, to enhance provider awareness and participation in VFC and other immunization activities, to improve data systems such as the immunization registry, and to increase the immunization program’s coordination with other key health and human services agencies, including Medicaid and WIC.

Coordination with Medicaid, in particular, could be important in raising immunization rates, since many low-income children are enrolled in the Medicaid program.

A LEGISLATOR’S VIEW

Dianne White Delisi, a member of the Texas legislature and of the IOM planning committee, offered a political perspective in the workshop deliberations. She noted that Texas has a population of about 21 million with an annual per capita income of about $27,000, which is less than the national average of $28,500. The state had the second highest birth rate in the nation in 1999, and 45 percent of schoolchildren in Texas are eligible for free school lunches. In terms of immunization issues, most legislators are committed to meeting the needs of children, but many of them arrive unfamiliar with the current array of recommended vaccines or the challenges of delivering immunization services. Representative Delisi emphasized the importance of educating legislators about these issues. She described her own education through her involvement in the early 1990s in a statewide immunization project called Shots Across Texas, in which Dr. Smith also participated during his tenure as state health commissioner. Representative Delisi is now involved in efforts to revitalize the project in response to the state’s low immunization rates for 2-year-olds.

In terms of the budgetary and financing aspects of immunization, the

state adopted a “first-dollar” coverage law in 1999, which requires health plans and insurers under state jurisdiction to cover immunizations without requiring copayments or prior fulfillment of plan deductibles. The legislature is considering several immunization issues with budgetary implications, including the cost of purchasing additional vaccines and policies for the state’s immunization registry. An evaluation of the operation of the Texas Department of Health (Bomer, 2001) has proposed that statutory changes be made to shift from an “opt-in” to an “opt-out” system for the immunization registry (that is, inclusion of a child in the registry unless parents request exclusion) and to give all immunization providers access to the registry. These steps are likely to help in efforts to improve the state’s immunization coverage rates but also raise concerns in the legislature about privacy and parental rights. Nevertheless, Representative Delisi sees support for these proposals, as well as for using the registry to support a statewide immunization recall and reminder campaign. She concluded by urging a stronger collaboration between the public health system and primary care providers to meet the state’s immunization needs.

A LOCAL PERSPECTIVE

Local health departments play an important role in implementing certain elements of the state’s immunization program. They often operate clinics to provide vaccinations to children and adults in the community. With the advent of VFC, however, they have also taken on responsibility for recruiting private providers to participate in the program and for assessing immunization rates in public clinics and private provider practices. Jorge Magaña, director of the El Paso City-County Health and Environmental District, discussed his experience in El Paso with these changing roles and responsibilities.

Dr. Magaña noted several challenges in serving the El Paso area. The population includes many new immigrants who are often highly mobile and have limited education. Children frequently need catch-up immunizations, and many families have fears about the vaccines. Dr. Magaña noted that physicians have been leaving El Paso, and the area is underserved compared with other parts of the state. In 2001, 104 El Paso providers, primarily pediatricians and family physicians, participated in VFC, down from 128 providers in 1998. In addition, a prenatal care program in health department clinics that had helped link new mothers with immunization services has been transferred to local hospitals and is less likely to serve the uninsured.

Before 1994, the local health district provided most immunization services in El Paso, and the coverage rate for the 4:3:1 series had reached

81 percent in 1994. As of 2000, providers who participate in VFC are administering 70 percent of immunizations in the area, but coverage rates have dropped to 71.5 percent. In 1997, a state-sponsored pilot study demonstrated that VFC providers in El Paso were not assessing immunization coverage accurately and also were not documenting children’s immunization histories. Since 1997, the health district has worked with limited numbers of providers who participate in VFC to conduct systematic record assessments using CDC’s AFIX (assessment, feedback, incentives, exchange) program strategy, which includes use of the Clinic Assessment Software Application. With these assessments, immunization rates among participating providers rose from as low as 40 percent in 1997 to 90 percent or higher in 2000.

The assessment program requires considerable staff time and therefore creates a need for funding. Initially, state funds supported the work of three El Paso health district staff members on the assessment program. To respond to a growing demand for assessment services, Dr. Magaña obtained additional funding by turning to a local foundation, the El Paso del Norte Health Foundation. The foundation made a 2-year grant through the El Paso County Medical Society for a collaborative effort with the health district. The assessment program has been effective in raising immunization rates in El Paso and in helping the health district build partnerships in the community and with the state health department. Dr. Magaña emphasized, however, that foundation funding was only a short-term means of supporting the assessment program and that other funding solutions are necessary to sustain those activities.