5

Improving Protection Through Oversight and Data and Safety Monitoring

To advance the continuing safety of individuals who volunteer to participate in research, the Human Research Participant Protection Program (HRPPP) (“protection program” or the “program”) is responsible for systematically collecting and assessing information about the conduct of human research activities within its purview. Research involving humans is a data- and labor-intensive activity, from the inception of a protocol through its implementation to final completion and reporting of results. Ongoing review and monitoring is necessary to ensure that emerging information obtained from a study has not altered the original risk-benefit analysis. Yet in 1998, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) wrote that Institutional Review Boards1 (IRBs) do not adequately conduct ongoing reviews and that, in general, such reviews are “hurried and superficial” (OIG, 1998a,b). In addition to complying with the regulatory requirements for IRBs to conduct ongoing monitoring and review,2 additional efforts are needed so

that protection programs can improve the oversight and monitoring of ongoing studies.

Mechanisms should be in place to track protocols and study personnel and provide assurances that data are valid and are collected according to professional standards. These tasks should be accomplished in a way that safeguards participants’ safety, privacy, and confidentiality within the system. Protection measures should be monitored by various means at all levels of oversight—from the government to the research organization to the investigator—to ensure that informed consent has been properly obtained and that all adverse events have been identified and promptly reported by the investigator to the appropriate institutional body, sponsor, and federal agency(ies). In turn, investigators and participants require assurances that the process is being handled responsibly by the protection program, that federal rules are being applied, and that those charged with these responsibilities have been appropriately trained.

Although regulations and guidance are available from both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to direct IRBs, investigators, and sponsors in reporting and evaluating adverse events, confusion remains. Moreover, other entities not considered in the federal regulations, such as Data and Safety Monitoring Boards/ Data Monitoring Committees (DSMB/DMCs), are beginning to play an increasingly important role in safety monitoring (DeMets et al., 1999).

In 2001, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) stated that “For the purpose of continuing review, IRBs should focus their attention primarily on research initially determined to involve more than minimal risk” (2001b, p.112). NBAC reasoned that in research involving high or unknown risks, “the first few trials of a new intervention may substantially affect what is known about the risks and potential benefits of that intervention” (2001b, p.112). For minimal risk studies, NBAC stated the following:

Continuing review of such research should not be required because it is unlikely to provide any additional protection to research participants and would merely increase IRB burden. However, because minimal risk research does involve some risk, IRBs may choose to require continuing review when they have concerns. In these cases, other types of monitoring would be more appropriate, such as assessing investigator compliance with the approved protocol or requiring reporting of protocol changes and unanticipated problems. Although such efforts might fail to detect some protocol problems, the resource requirement inherent in conducting continuing reviews for all protocols and the distraction of the IRB’s attention from riskier research do not justify devoting a disproportionate amount of resources to continuing review (2001b, p.112).

This committee concurs with NBAC’s conclusion and thus focuses in

this chapter on a discussion regarding recommendations to require and improve safety monitoring of all higher-risk studies, particularly clinical trials.

Recommendation 5.1: Research organizations and Research Ethics Review Boards should have written policies and procedures in place that detail internal oversight and auditing processes. Plans and resources for data and safety monitoring within an individual study should be commensurate with the level of risk anticipated for that particular research protocol.

This chapter addresses the following topics surrounding the protection program’s responsibilities for oversight and data and safety monitoring:

-

government, industry, and local oversight;

-

internal tracking mechanisms;

-

data and safety monitoring within the program;

-

the role of the Research ERB;

-

data security;

-

privacy and confidentiality provisions;

-

reporting information to participants;

-

communication among program components; and

-

resource needs.

(Box 5.1 provides definitions for many of the terms and acronyms used throughout this chapter.) However, not all research with humans requires this level of intensive monitoring and safety review.

GOVERNMENT REGULATION OF RESEARCH

Through federal regulations, the government has established a system of protections for research participants that involves requirements for minimizing risk and monitoring the safety of studies that are under way. Seventeen federal agencies and departments adhere to the Common Rule (45 CFR 46, Subpart A), which is a set of identical regulations codified by each agency that applies to human research conducted or sponsored by the agency. In addition, FDA has its own regulatory authority over research involving “food and color additives, investigational drugs for human use, medical devices for human use, biological products for human use being developed for market, and electronic products that emit radiation” (21 CFR 50,56). The mechanisms by which oversight is generally conducted are described below. This system of protections, however, applies only to research that is federally funded by an agency that is subject to the Common Rule or that is subject to FDA review and approval.

|

Box 5.1 510(k) Notification: A marketing submission to FDA providing evidence that a medical device is “substantially equivalent” to a currently marketed device. A 510(k) clearance, not an approval, is granted for marketing these devices. Medical devices requiring a 510(k) clearance rather than a Premarket Approval (PMA) are typically lower-risk medical devices and devices that are substantially equivalent to devices that have been on the market since 1976 (pre-amendment devices). These devices also do not require an investigational device exemption for conducting clinical studies. Audit: A systematic and independent examination of study-related activities and documents to determine whether those activities were conducted and the data recorded, analyzed, and accurately reported according to the protocol sponsor’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and the applicable regulatory requirements. Biologic License Application (BLA): An FDA submission for marketing approval of specified biotechnology products such as products manufactured by recombinant DNA technology and monoclonal antibody products. A BLA is submitted to FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Common Rule: The colloquial name for 45 CFR 46, Subpart A, the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. This regulation consolidates requirements for IRB review and informed consent to participate in human subject research. It applies to any DHHS-funded research conducted on human subjects as well as that funded by 15 other agencies. FDA has promulgated its own regulations (21 CFR Parts 50 and 56) for FDA-regulated research, which closely mirror the Common Rule. Both sets of regulations apply when research is FDA-regulated and federally funded (wholly or partially). Continuing Review of Research: The concurrent oversight of research on a periodic basis by an IRB. In addition to the at least annual reviews mandated by federal regulations, reviews may, if deemed appropriate, also be conducted on a continuous or periodic basis. Data and Safety Monitoring Board/Data Monitoring Committee (DSMB/DMC): An independent data monitoring committee that may be established by the sponsor to assess at intervals the progress of a clinical study, the safety data, and the critical efficacy endpoints, and to advise the sponsor whether to continue, modify, or stop a study. The terms Data and Safety Monitoring Board, Monitoring Committee, Data Monitoring Committee, and Independent Data Monitoring Committee are synonymous. OR A committee of scientists, physicians, statisticians, and others that collects and analyzes data during the course of a clinical trial to monitor for adverse effects and other trends (such as an indication that one treatment is significantly better than another, particularly when one arm of the trial involves a placebo control) that would warrant modification or termination of the trial or notification of subjects about new information that might affect their willingness to continue in the trial. |

|

Federalwide Assurances (FWA): Under federal regulations, an approved Assurance of Compliance must be in place for any institution that is engaged in federally funded human subject research. This written Assurance of Compliance documents the research institution’s understanding of and commitment to comply with federal standards for the protection of the rights and welfare of the subjects enrolled in that research. For research funded by DHHS, these standards are found in 45 CFR Part 46. Assurances are awarded and monitored by the DHHS Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). In December 2000, OHRP issued a plan to require each institution engaged in research activities, either on its own or as a subcontractor, to hold its own FWA. A single FWA would cover all research conducted at that institution. The FWA would be renewed every three years, and compliance would be monitored by OHRP. A revised version of the FWA was issued in March 2002. Form FDA 483: Written documents describing objectionable practices observed during an FDA inspection of a sponsor, IRB, or research site. Good Clinical Practice (GCP): A standard established by the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) for the design, conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, recording, analyses, and reporting of clinical studies that provides assurance that the data and reported results are credible and accurate and that the rights, integrity, and confidentiality of study subjects are protected. (E6 is the relevant guideline.) Investigational New Drug Application (IND): Refers to the regulations in 21 CFR 312. An IND that is in effect means that the IRB and FDA have reviewed the sponsor’s clinical study application, all the requirements under 21 CFR 312 are met, and an investigational drug or biologic can be distributed to investigators. Monitor or Monitoring: The act of overseeing the progress of a clinical study and of ensuring that it is conducted, recorded, and reported in accordance with the protocol, SOPs, GCP, and applicable regulatory requirement(s). New Drug Application (NDA): An FDA submission for marketing approval of new drugs. An NDA is submitted to FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Premarket Approval (PMA): An FDA submission for marketing approval of new medical devices that impart significant risk. A PMA is submitted to FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Product License Application (PLA): An FDA submission for marketing approval of all other CBER-regulated products except those that require a BLA. This includes but is not limited to blood products, vaccines, and allergenic extracts. Standard Operating Procedure (SOP): A document that specifies all the operational steps, acceptance criteria, personnel responsibilities, and materials required to accomplish a task. |

Other mechanisms and authorities also are in place to monitor and oversee the research enterprise. For example, in 1992 the Office of Research Integrity was consolidated within DHHS and charged with overseeing investigator misconduct and prevention activities in DHHS-funded research, except for those investigators that fall under the jurisdiction of FDA. Investigative and oversight units of the Executive Branch and Congress have the authority to oversee various aspects of the research enterprise and report on its status. In addition, agencies that sponsor research reserve the right to revoke, suspend, or terminate funding if the research grantee or contractor is in violation of federal policy. Actions also can be taken at the recommendation of an agency’s Office of Inspector General, and Congress reserves the right to intervene through the budget process or its investigatory powers.

These activities at the federal level provide an overarching system of protections that are operationalized, implemented, and responded to by research institutions and programs. A central role of these agencies is the provision of monitoring and oversight. However, the two leading agencies responsible for regulating the bulk of human research in the United States— the DHHS OHRP and FDA—should do more to harmonize regulatory requirements in these areas; share the results and findings of oversight activities; and provide useful guidance for investigators, research institutions, and HRPPPs to facilitate the enhancement of protection functions.

Monitoring by the Office for Human Research Protections

DHHS is the federal agency in which the bulk of clinical research and its oversight occurs. Eighty percent of federally funded research with human participants is conducted by one DHHS agency, NIH (NBAC, 2001c). NIH was also the original home of the major regulatory office in this area—the Office of Protection from Research Risks (OPRR), which was created in 1972 within NIH and charged with the protection of research participants involved in all DHHS-funded research, including NIH’s intramural and extramural research programs. In June 2000, OPRR was replaced with OHRP, which was moved out of NIH and charged with protecting human research subjects in biomedical and behavioral research across DHHS and other federal agencies that follow the Common Rule (DHHS, 2000b). Thus, OHRP monitors compliance with regulations that specifically address IRBs, informed consent, vulnerable populations, and other issues directly related to the protection of participants as addressed in the federal regulations. Data verification, however, is not included in OHRP’s direct mandate.

OHRP operates on a system of Written Assurances of Compliance, in which the institution assures its compliance with the regulations. The office revised its assurance process for domestic institutions in December 2000, replacing the previous Single and Multiple Project Assurances (SPAs and MPAs) with a Federalwide Assurance (FWA).3 OHRP conducts periodic oversight evaluations “for cause,” based on “all written allegations or indications of noncompliance with the HHS Regulations derived from any source” (Koski, 2000).

If OHRP finds an institution to be noncompliant, it can suspend all or a portion of its research activities at the institution and revoke its MPA/ FWA. Between 1990 and June 2000, OPRR issued 40 Determination Letters to institutions and organizations citing violations of their MPA and in some cases suspended research activities until violations were addressed (NBAC, 2001b). Between July 2000 and May 2002, OHRP issued 289 Determination Letters.4 This increase in the number of Determination Letters is due in part to increased surveillance activity on the part of OHRP, but also reflects the volume of research currently being conducted and the increased instances of noncompliance identified nationwide.

Other OHRP initiatives include a new system for IRB registration, a quality improvement program directed to research organizations, and the sponsorship of the Award for Excellence in Human Research Protection.5 The latter two initiatives are particularly significant, as they represent a shift in the manner that OHRP and its predecessor agency, OPRR, have traditionally conducted business. Although ensuring compliance through monitoring and site visits is essential to maintaining the integrity of the system, to maximize its impact, OHRP should expend more resources on facilitating the work of protection programs to meet compliance goals. One way to do so is through informing the research organization of the outcome of its compliance assessment and by more proactively assisting programs in meeting regulatory requirements.

DHHS should provide additional resources to OHRP to build its capacity to develop useful guidance and facilitate educational and problem-solving activities to better complement its regulatory compliance mandate.

|

3 |

In March 2002, revised language for the FWA agreement was issued by OHRP. This language can be reviewed at ohrp.osophs.dhhs.gov/humansubjects/assurance/fwas.htm. |

|

4 |

Included within the count of 289 Determination Letters are instances in which a single institution received multiple letters. OHRP maintains determination letters from July 2000 forward at ohrp.osophs.dhhs.gov/detrm_letrs/lindex.htm. |

|

5 |

The Award for Excellence in Human Research Protection was established by the Health Improvement Institute. OHRP and DHHS are the funding sponsors for the award, which acknowledges three different categories of excellence. For more information, see www.hii.org. Friends Research Institute has also instituted an award for research ethics. For more information, see www.friendsresearch.org/award.html. |

In addition, OHRP should continue to advance its activities to emphasize an oversight system based on routine surveillance and proactive performance improvement (see, for example, Recommendation 3.8) rather than concentrating solely on compliance investigations and reporting of non-compliance and suspected violations.

Regulatory Requirements for Continuing Review

The federal regulations at 45 CFR 46.109(e) require that “an IRB shall conduct continuing review of research covered by this policy at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk, but not less than once per year, and shall have authority to observe or have a third party observe the consent process and the research.” Regular, continual review is necessary to ensure that emerging data or evidence have not altered the risks or potential benefits of a study in such a way that risks are no longer reasonable.

The conduct and adequacy of such reviews have been considered erratic and ineffective for some time. A 1975 study of 61 institutions conducted for the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (National Commission) found that half of the IRBs seldom or never reviewed interim reports from investigators (Cooke and Tannenbaum, 1978). The National Commission recommended, at a minimum, annual continuing review for research studies involving more than minimal risk or vulnerable populations (1978). In 1981, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research concluded that “many IRBs do not understand what is expected in the way of ‘continuing review’…[and] the problems manifested in these studies clearly need attention” (1981, p.47). In 1998, the DHHS OIG found that IRBs “conduct minimal continuing review of approved research” and that the reviews are “hurried and superficial” (OIG 1998a,c). In 2001, NBAC wrote that “Because the federal regulations are incomplete in describing what should be considered in continuing review, it is understandable that IRBs do not always conduct appropriate review. Thus, additional guidance is needed” (2001b, p. 112). This committee concurs with the NBAC statement and encourages OHRP to pursue the necessary activities to meet this need.6

|

6 |

The committee commends OHRP for issuing such guidance on July 11, 2002 (ohrp.osophs.dhhs.gov/humansubjects/guidance/contrev2002.htm), although the committee did not have the opportunity to review or assess the guidance. |

Monitoring by the Food and Drug Administration

Recommendation 5.2: The Food and Drug Administration and the Office for Human Research Protections should notify the research organization(s) under whose jurisdiction a study was conducted of any deficiency warnings as well as any responses to such warnings. The research organization should share this information with the relevant Research Ethics Review Board (Research ERB). Likewise, monitoring reports prepared by or for sponsors that identify serious violations should be submitted to the principal investigator and the designated Institutional Review Board of record. In multicenter trials, these reports should be submitted to the central Research ERB, if applicable. All such communications should occur in a prompt and timely fashion.

The most extensive system of data and safety monitoring exists in the area of clinical trials subject to FDA review and approval. FDA inspects investigators, IRBs, and occasionally sponsors, to verify compliance with GCP. FDA does not have the resources to inspect every investigator and thus is more likely to focus inspections on those entities that enroll large numbers of participants. Foreign as well as U.S. investigators are subject to inspection, but U.S. investigators are more likely to be scrutinized.

The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act7 promulgated new regulations to improve protections for persons involved in clinical research investigations. In addition to proving efficacy, sponsors were expected to monitor the progress of studies, and investigators were required to maintain case histories for enrolled participants that included reports of serious adverse events.

In 1977, a distinct oversight unit within FDA was formed to provide ongoing surveillance of clinical research investigations. The Bioresearch Monitoring Program audited the activities of clinical investigators, monitors, sponsors, and nonclinical (animal) laboratories. It was intended to ensure the quality and integrity of data submitted to FDA for regulatory decisions, as well as to protect research participants.

The regulations that permit FDA to consider the validity of data submitted to it are contained in 21 CFR 312 and 21 CFR 812. In 1981, FDA published final regulations at 21 CFR 50 and 56 that cover the protection of human subjects and IRBs and were intended to complement the regulations issued the same year by DHHS (45 CFR 46). Thus, FDA inspects data to ensure their validity in support of an application, as well as the protec-

|

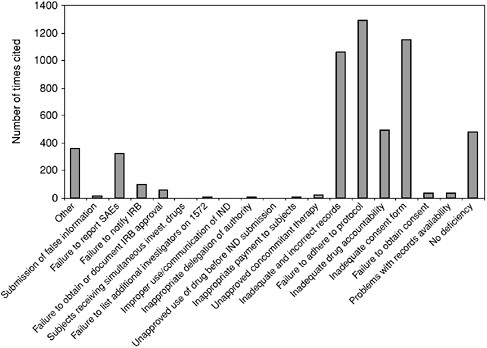

Box 5.2 From June 1977 through January 1994, FDA performed 3,092 onsite inspections and discovered that 56 percent of these sites had problems with consent forms. Other deficiencies included the following: 29 percent of the sites had not adhered strictly to the protocols; 23 percent kept poor records; 22 percent were unable to properly account for the drugs they had dispensed; 12 percent had problems with their IRBs; and 3 percent were missing a significant number of their records. Still, during this same interval, extremely serious problems—including those that led to barring of investigators from conducting clinical studies—had decreased from 11 percent of total trials to 5 percent (Cohen, 1994). Figure 5.1 depicts the number and category of form FDA 483: “Inspectional Observations” deficiencies issued to clinical investigators who have performed studies under an IND. The data reflect clinical investigator inspection files that are closed with a final classification by FDA. |

tion of the individuals from whom the data were collected. FDA may also audit the IRB of record for an inspected study, as well as investigate consumer complaints or reports from whistleblowers. If FDA finds that an investigator is noncompliant, he or she can be disqualified from future studies.

FDA inspections of clinical investigators generally are conducted after the trial is completed and a new drug application has been submitted for review (Box 5.2). NBAC has noted that

Most FDA inspections of investigators are conducted after the trial is complete. Thus, any detected violations of regulations to protect research participants are found after the point when participants in the particular trial could have received adequate protection. However, the inspections are helpful in improving compliance of investigators and, therefore, protection of participants in future research (2001b, p.52-53).

However, a significant gap in this oversight exists in situations in which a sponsor elects not to submit an application to FDA [NDA, PMA, BLA, PLA, and 510(k)] due to the toxicity or ineffectiveness of the candidate compound or medical device, because the termination of a trial before the submission of an application for approval will eliminate the trigger for an FDA inspection.

To improve the Research Ethics Review Board’s (Research ERB’s) capability to oversee participant protection, the committee recommends that any monitoring report for studies under a board’s purview be shared with that board. This would not affect ongoing oversight, but would alert a Research ERB to potential problems. It would be essential for the Research

FIGURE 5.1 Form FDA 483 Deficiencies Issued by CDER Since 1990

NOTE: This table is based upon data from 483s issued in connection with FDA audits of human investigational drug studies. The analysis for the table was conducted by Center for Clinical Research Practice utilizing a listing of 483s issued over a span of 10 years (ending in January, 2002) by Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and compiled by CDER (available at http://www.fda.gov/cder/regulatory/investigators/default.htm). The information does not include data from the Center for Devices and Radiological Health or the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

ERBs to also see the investigator’s response to the deficiency warning (and that of the research organization, as applicable), as the response often sheds light on the inspection findings and clarifies how future problems can be averted.

Types of Deficiency Warnings to be shared would include Letters of Determination and 483s, including those applying to manufacturing problems. Warning letters should be sent or at least copied to the head of the research organization for distribution to those who need to know (e.g., the Research ERB), as is the practice for industry Chief Executive Officers; and, again, investigator’s responses also should be forwarded.

Responsibility of Research Sponsors

A report issued by the Drug Research Board (DRB) of the Division of Medical Sciences of the National Research Council supported FDA’s approach to monitoring, which sought to place the burden of responsibility for clinical investigations on the research sponsor (Kelsey, 1991). The DRB agreed with FDA that the sponsor should assume responsibility for 1) the clinical competency of its investigators; 2) the adequacy of the facilities being used for the clinical investigations; and 3) the investigators’ understanding of the nature of the drug under investigation as well as the obligations that go with undertaking the investigation of that drug.

The DRB affirmed the sponsor’s responsibility to ensure through periodic site visits the accuracy of the data, the adequacy of the research records, and adherence to the protocol. The DRB also affirmed the responsibility of a sponsor to terminate studies as deemed advisable, relate adverse effects of drugs discovered in animals to potential effects in humans, and ensure that participant consent was obtained and institutional review undertaken. Finally, the DRB recommended that FDA should not be responsible for active monitoring, but rather should monitor on an occasional basis and when there is reason to question data. It is not surprising, therefore, that the program for ensuring data validity became known as “monitoring the monitor” (Kelsey, 1991).

According to the regulations, “A sponsor shall select a monitor qualified by training and experience to monitor the progress of the investigation.”8 In FDA-regulated studies, data validity monitoring is conducted routinely by 1) industry monitors during site visits who conduct ongoing review of research data and 2) DSMB/DMCs engaged to look at safety data independently, with participant protection as their priority. Sponsors of FDA-regulated studies monitor all their investigators regularly (or at least they should).

Sponsors regularly monitor investigator compliance with GCP and with specific study protocol, including the degree of participant protection achieved. Many sponsors transfer this obligation to “monitors” who are employed by contract research organizations (CROs) and are therefore once removed from direct contact with the investigator site. The sponsor, however, does see the site visit monitoring report and remains ultimately responsible for the quality of the data and the conduct of the study.

Contract Research Organizations

In 1987, FDA recognized CROs as regulated entities, and provided that authority for the conduct of a study could now be delegated by a sponsor to a CRO.9 Sponsors are expected to verify the accuracy of reports submitted by a CRO in support of a marketing application, thereby holding sponsors accountable for entities acting as their proxy.

In 1988, FDA published guidelines encouraging sponsors to enact policy that provides for monitors to make frequent site visits, review investigators’ adherence to their protocols, ensure that investigators communicate as necessary with the IRB of record, and ensure that records are properly kept (FDA, 1998). Pharmaceutical companies, or a CRO acting on behalf of the sponsor, generally send monitors to visit each participating site every 6 to 10 weeks to monitor the progress of the study, verify the accuracy and completeness of data submitted in case report forms, and assess investigator compliance with regulations and GCP.

The Need for Collaboration and Harmonization of Federal Monitoring Activities

Although FDA retains its enforcement authority for participant protections in FDA-regulated drug, biologic, and medical device clinical trials, it is hoped that the increased centralized oversight provided by OHRP will lead to more consistent and effective guidance in human participant protections across federal agencies. In addition, the agencies should collaborate on providing useful guidance for investigators and protection programs. Finally, the entire research community would benefit from knowing annually the results and conclusions of federal inspections conducted each year. This would provide a basis on which programs could improve compliance and incorporate federal findings into their quality assurance and improvement programs (see Chapter 6).

Recommendation 5.3: Federal oversight agencies should harmonize their safety monitoring guidance for research organizations, including the development of standard practices for reporting adverse events.

Harmonization is required regarding 1) safety monitoring needs at various levels of risk (e.g., high-risk research such as gene transfer studies that are likely to require frequent monitoring) and 2) a baseline level of monitoring/chart audits that would be acceptable to ensure compliance at

each risk level. In turn, each program should specifically address its internal monitoring and auditing processes for protocols at the various risk levels.

The appreciation and recognition of adverse events is particularly important in the context of clinical research, specifically in early phase clinical trials when little is known about the action of a test compound during initial exposure in humans and the determination of the safety profile is a critical marker. Indeed, the recognition and reporting of adverse events, coupled with appropriate intervention strategies, may constitute the most important function for research personnel in protecting research participants from harm and the population at large from subsequent exposure to a toxic or dangerous device or agent. Postmarketing surveillance and continued reporting of adverse events, as occurs through the MedWatch mechanism established by FDA, is particularly critical for drugs that receive approval on FDA’s fast-track mechanism.

Although the exact magnitude of adverse events in the general population and in clinical trials in particular is unknown, the incidence of adverse drug experiences related to the investigational and subsequent therapeutic use of drugs and biologics is an important health concern. These events may be attributable to a variety of factors, including inappropriate prescription of the drug(s) by physicians (e.g., improper dosing or inattention to drug interactions). In the research context, both FDA regulations and the Common Rule require that adverse events be reported.10 The Common Rule requires that adverse events be reported to the IRB of record, and FDA regulations contain requirements for the reporting of adverse events during all phases of product development as well as some post-approval reporting requirements. IRBs report that they are inundated with adverse event reports, but are provided with little guidance on how to analyze or make sense of them (NBAC, 2001b; OIG 1998a,b). In 1998, the DHHS OIG found that investigators were often frustrated and confused about what to report and to whom, and many were required to report adverse events separately to sponsors, NIH, the IRB, and FDA (OIG, 1998a,b). Complex and fragmented regulations contribute to a system of monitoring that is ripe for error. As well described by NBAC in 2001, adverse event reporting mechanisms should be immediately addressed to harmonize and simplify reporting requirements and timelines and to improve safety (2001b). NIH’s requirements, which differ from those of FDA and are not clearly linked to the regulatory language, contribute to significant confusion on the part of investigators. FDA’s definitions also are not entirely clear (for example, regarding investigational drugs versus devices). However, its system for

adverse event reporting is developed well beyond that of any other agency and is also the most widely used by investigators conducting clinical trials of FDA-regulated products.

Issues that require clarification by and harmonization among federal agencies include 1) the definition of an adverse event, 2) report format, 3) report recipients, and 4) reporting time lines. A standard reporting algorithm would be extremely useful and could greatly enhance compliance.

Finally, understanding basic pathophysiology and pharmacology is required for a full appreciation of the nature, cause, and diagnosis of an adverse drug reaction. Training in these areas should be offered as part of an institution’s ongoing continuing education program for relevant research staff, as only research staff that have the appropriate training and education should be evaluating research participants for adverse events. Clinical investigators should receive specific instruction about assigning a causal relationship of an adverse event to the drug, biologic, or device under investigation; Research ERBs should be provided guidance on how to interpret and respond to such reports; and clinical trial participants should be instructed on how to recognize and report adverse events to study personnel.

Recommendation 5.4: The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services should issue a yearly report summarizing the results of research oversight activities in the United States, including Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) findings from inspections conducted during the previous year. OHRP and FDA should issue joint and regular statements containing the type of content currently found within “FDA Information Sheets.”

FDA’s Office for Good Clinical Practice could spearhead this initiative to provide joint information regarding inspection findings from OHRP and FDA. Direct collaboration with OHRP should be strengthened, and the FDA office could be jointly staffed by both agencies. A set of recommendations to improve human participant protection compliance based upon inspection findings could provide valuable guidance to protection programs.

OVERSIGHT BY FEDERAL RESEARCH AGENCIES

Although at least 16 federal agencies support research with human participants, DHHS is the largest federal sponsor of research involving human subjects (NBAC, 2001c). In FY 1999, NIH supported nearly 83 percent of all federally funded research in the United States (NBAC, 2001c). As such, NIH is the federal agency most involved in monitoring activities and is the focus of the following section.

National Institutes of Health

Recommendation 5.5: When protocols warrant high levels of scrutiny because of risk to the participant, National Institutes of Health-sponsored clinical trials (intramural, extramural, and cooperative study groups) should be monitored with the same rigor and scrutiny as trials carried out through an investigational new drug application.

NIH Centers and Institutes are responsible for the oversight and monitoring of participant safety and data integrity for all NIH-sponsored clinical trials (intramural and extramural). In 1967, the National Heart Institute commissioned a report that recommended specific structural and operational components for NIH-sponsored cooperative trials (Heart Special Project Committee, 1967). Known as the Greenberg Report, it called for committee oversight, including the establishment of an Advisory and Steering Committee, protocol chair, and data coordinating center, and a mechanism for independent interim analysis of accumulating data that could call for premature study termination when warranted. DSMB/DMCs are the modern expression of this committee and are now routinely established for Phase 3, multisite clinical trials employing interventions that could pose a potential risk to participants. NIH policy further mandates a data and safety monitoring plan (DSMP) for all Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials (NIH, 2000a).

Research participant protections in the NIH extramural program are monitored by OHRP and FDA (if a research protocol involves an FDA-regulated product) through the relevant research organization’s HRPPP. Activities of the intramural program are monitored by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research, which oversees the multiple IRBs that sit for the various Institutes and the training of NIH clinical investigators. NIH’s Office of Biotechnology Activities oversees gene transfer clinical trials through its management of the NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, which ensures additional safeguards on the conduct of gene transfer clinical trials.

The committee endorses NIH’s requirement for DSMPs for all clinical trials, and further supports its extension to all studies involving more than minimal risk. However, the committee believes additional guidance is needed regarding what is expected of such plans. As appropriate, guidance provided by FDA and ICH for monitoring of investigations could be applied to federally funded studies (FDA, 1998; ICH, 1996). Further guidance is also needed regarding how to fund the DSMP requirement and how to assure compliance with established plans.

To meet this need, NIH could initiate an internal program based on FDA compliance program guidance or require that institutions conduct such reviews as a condition of receiving funds.

DATA AND SAFETY MONITORING BY THE PROGRAM

Data and Safety Monitoring Plans

Federal regulations require that protocols submitted under an IND include detailed descriptions of the “clinical procedures, laboratory tests, or other measures to be taken to monitor the effects of the drug in human subjects as to minimize risk.”11 As mentioned above, NIH is now requiring that all Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials have a DSMP.

Data Validity and Safety Monitoring

The practice of establishing data validity and safety monitoring is most firmly established in drug, biologic, and device studies subject to FDA review and approval. Data submitted to FDA in support of a marketing application must be complete, accurate, and verifiable, as the eventual safety of millions of people rests on the accuracy and integrity of data collected regarding a product’s efficacy and toxicity profile. Although behavioral studies conducted to test a hypothesis do not expose individuals to an investigational drug, device, or biologic, they nevertheless draw conclusions that could affect the lives and health care of millions. These data should therefore also be verified and the methods of collection monitored to ensure data validity and participant protection. The frequency and breadth of these monitoring activities should be proportional to the degree of risk assumed by the participant, as determined by the Research ERB.

The investigator is responsible for ensuring that any study conducted is scientifically sound and implemented according to standards of ethical conduct and, as appropriate, GCP, by a trained and knowledgeable research team. It is the responsibility of the research organization to ensure that policies and SOPs are written and updated for study conduct and participant protection. The research organization should ensure that these policies and procedures are followed by all individuals conducting research under its jurisdiction. Mechanisms to ensure compliance include monitoring and auditing activities that should be ongoing and independent of the investigative site.

Monitoring the data generated and the research activities associated with the conduct of a protocol involves many distinct activities, including but not limited to the following:

-

assuring adherence to the approved protocol and amendments;

-

verifying that all participants provided informed consent before the institution of any study-related procedures;

-

reviewing records to confirm protocol eligibility;

-

reviewing records to determine compliance with the protocol and study intervention;

-

properly storing, dosing, dispensing, and tracking investigational agents;

-

verifying that data submitted are supported by source documents (paper or electronic);

-

reporting adverse events to the Research ERB and sponsor completely and in a timely manner;

-

ensuring that changes in the protocol are submitted and approved by the Research ERB before implementation; and

-

ensuring the confidentiality of participant data.

The Role of the Research ERB in Safety Monitoring

Most institutions are familiar with risk assessment vis-à-vis the liability exposure of the organization. However, the principles of risk in clinical research need to be applied from the perspective of the participants and their exposure to risk, whether that risk is imposed by an investigational agent or through a breach of confidentiality. Determination of risk to a study participant would thus be a reasonable yardstick for allocating resources and personnel for program monitoring activities. General guidance in this area could be provided by the Research ERB at the time of initial review. Suggestions for risk assessment could include high-, medium-, and low-risk categories with monitoring resources focused primarily in the high-risk area, leaving medium- and low-risk studies subject to selective monitoring activities.

The Research ERB could assign a risk category to each study reviewed, and this assessment would provide oversight guidance for the program. Studies classified as “high-risk” would require more intensive and frequent monitoring of data and compliance with human participant protections. A random sample of medium-risk studies would provide random checks within the system and serve as an educational opportunity to instruct research staff. Less-than-minimal-risk studies would not require onsite visits, just as they often are not subject to continuing review by the Research ERB.

Monitoring the Consent Process

The informed consent process is fundamental to an effective participant protection system, and, therefore, the integrity of this process should be monitored over the course of a study. As previously discussed, it is the responsibility of the Research ERB to review and approve the original consent process and consent form presented to participants. In addition, once a study is under way, the Research ERB should monitor whether

changes are required in the informed consent process based on the emerging study data.

The Research ERB could utilize a variety of mechanisms to ensure that informed consent is an ongoing, dynamic process that is responsive to participant needs and emerging data that could alter the ethical aspects of the study. Examples include the following:

-

video presentations of informed consent,

-

selected monitoring of consent by Research ERB staff,

-

administering portions of the consent document through the Research ERB, and

-

appointing an ombudsman for participants.

In performing the monitoring function, the Research ERB staff should focus on protection issues specifically centered on the consent process, recruitment practices, and adverse event reporting activities. The Research ERB office could function as an ongoing educational resource for these particular program activities.

Role of the Program in Data Monitoring

Investigators and institutions should take a proactive role in ensuring the validity and integrity of the data generated at each investigative site. Principal investigators (PIs) should assume the overall responsibility for the ethical and scientific conduct of research activities as individual participants are recruited, enrolled, and followed during a study by appropriately educated and trained research staff. For clinical trials, SOPs and procedures that are based on regulations and GCP should be adopted and applied throughout the research organization (ICH, 1996).

Institutional monitors could focus on source document verification, protocol adherence, and regulatory compliance, which would include chart reviews, regulatory file documentation, and case report form verification with source documents. Individuals not employed by the PI or directly involved with the conduct of the study should perform the monitoring functions.

DATA AND SAFETY MONITORING BY AN INDEPENDENT BODY

Recommendation 5.6: All studies involving serious risks to participants, enrolling participants with life-threatening illnesses, or employing advanced experimental technologies (e.g., gene transfer) should

assign an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board/Data Monitoring Committee.

The committee believes that all studies involving more than minimal risk should include a DSMP for review by the Research ERB.12 However, as trials increase in size and levels of potential risk—Phase 3 and 4 studies— more than a plan may be needed to enhance safety. Studies involving life-threatening illnesses generally secure a DSMB/DMC to perform interim analyses to evaluate toxicity and treatment outcomes as part of the overall trial design.

If the data strongly suggest a beneficial effect, harmful effect, or the probability that the study objective will not be addressed, the DSMB/DMC could recommend early termination of the trial, to protect the enrolled participants from prolonged exposure to an ineffective or harmful drug or intervention.

An interim analysis should determine if the study has met the scientific and ethical criteria established in the protocol to terminate it prematurely or allow the study to proceed to its planned completion. Whichever statistical methods are applied to testing outcome data during an interim analysis, the interpretation of the results is a complex process. To accomplish this interpretation in an unbiased and scientifically sound manner, the use of an independent DSMB/DMC that includes an appropriate mix of expertise has become an established norm for trials funded by industry and those funded by the federal government.

The primary responsibility of the DSMB/DMC should be to protect study participants from exposure to an inadequate or harmful intervention or continued participation in a futile study. In order to meet these goals, the membership of the DSMB/DMC should reflect its stated mission. Clinicians expert in the field of study, in combination with a statistician, epidemiologist, ethicist, and participant representative who have no vested interest in the findings of the board, are appropriate DSMB/DMC members. One model for the establishment of appropriate DSMB/DMCs would be the disease-specific boards that are currently active in clinical trial areas such as AIDS, cancer, cystic fibrosis, and cardiovascular disease. The targeted nature of these boards helps the individuals serving as members to develop the necessary level of expertise in the specific pathophysiology and safety concerns relevant to the disease. The nature of disease-specific “standing boards” such as these DSMB/ DMCs also facilitates the necessary education activities that should occur if DSMB/DMCs are to fulfill their ethical obligations.

According to a predetermined schedule based on projections for participant accrual, the DSMB/DMC meets to monitor the study’s overall progress and conduct interim analyses on treatment outcomes and toxicity data. At first, all toxicity and efficacy data may be considered without regard to treatment group. If further refinement of the review is needed, the data can be segregated into blinded treatment groups. The identity of each treatment group is disclosed only if absolutely necessary for a final decision.

Most DSMB/DMCs meet during both open and closed sessions. During the open session, the DSMB/DMC may meet with representatives of the data coordinating center, sponsor, FDA, and study chair. A summation report of the study’s progress is presented by the sponsor or its representative that focuses on operational issues, including recruitment, data management, and protocol design. During the closed session, the DSMB/DMC members review and discuss the study data. The board may recommend early termination, continuation of the study as planned, or continuation with modifications to the original protocol design and/or operational procedures.

To maintain its independence and confidentiality, the interim data that involve treatment outcome should be available only to DSMB/DMC members. It is also critical that any action by the board not be released in advance of an official report to investigators or the press. Unofficial or erroneous statements may dramatically affect the ongoing enrollment and integrity of the clinical investigation.

Recent Guidance from the Food and Drug Administration

In November 2001, FDA issued draft guidance entitled “Guidance for Clinical Trial Sponsors: On the Establishment of Clinical Trial Data Monitoring Committees” (2001a). According to FDA, the sponsor is responsible for ensuring that the DSMB/DMC operates under appropriate SOPs, and the guidance document offers some FDA perspective on criteria for establishing a DSMB/DMC, including committee composition, conflict of interest considerations, and other general considerations.

DSMB/DMCs should be convened according to guidelines provided by FDA when the study is under FDA purview, and according to NIH guidelines when a study is federally funded. In general, the size and composition of the DSMB/DMC may vary, but DSMB/DMCs should include appropriate expertise (e.g., clinical, scientific, statistical, and ethical). In addition, DSMB/DMC members and the DSMB/DMC as a whole should be independent from sponsors, investigators, and institutions.

NIH is the logical agency to take a strong lead in developing additional DSMB/DMCs, because it has had significant experience with this process.13

NIH also should develop funding mechanisms to expand such programs to ensure DSMB/DMCs have adequate resources for performing their protection functions.

COMMUNICATING THE RESULTS OF DATA AND SAFETY MONITORING

FDA regulations require that sponsors review all information relevant to the safety of a drug from any source, including epidemiological or clinical studies and animal toxicology data. This also covers domestic and foreign reports for both investigational and approved drugs and both published and unpublished reports. The sponsor is also required to file an IND safety report with FDA and all participating investigators within a specified timeframe when the adverse experience associated with the use of the drug is both unexpected and serious or when animal studies of mutagenicity, teratogenicity, or carcinogenicity demonstrate a potential risk for human subjects.14 The regulations further require that “significant new findings developed during the course of the research which may relate to the subject’s willingness to continue participation will be provided to the subject.”15

The regulations do not specify when or how the sponsor or investigator should inform subjects no longer participating in a study about reports of serious clinical or animal adverse events associated with a drug or biologic. Although traditionally the consent form has stated that participants will be informed of new findings, generally it is not stated when and how this information should be communicated.

For active participants, the ongoing consent dialogue between the investigator and participant would provide the ideal venue for informing participants of new information that may affect their future or current participation in a study. A Research ERB-approved signed addendum to the consent form could serve to document this communication. In addition, individuals who have completed a study or who have chosen not to continue their participation should also continue to be informed of any new findings, particularly new toxicology data from animal studies or serious adverse events that could have an effect on a participant’s current or future

health (e.g., primary pulmonary hypertension and cardiac valve damage associated with the use of fenfluramine and phentermine).

In general, trial results are not routinely reported to participants, but rather appear as articles in peer-reviewed journals. However, published articles generally do not appear for many months or even years after a study is completed, and participants would not necessarily have easy access to or knowledge of these reports. Therefore, efforts should be made to utilize other more direct means of informing participants of study results.

Sponsor Communication with Regulatory Agencies, Investigators, Monitors, and Data and Safety Monitoring Boards/Data Monitoring Committees

The regulations for FDA-regulated products during IND development studies detail specific sponsor reporting requirements to the agency.16 These include periodic progress and annual IND and Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) reports of safety data and protocol amendments. Sponsors are also required to inform investigators about “new observations discovered by or reported to the sponsor on the drug, particularly with respect to adverse effects and safe use.”17 These observations may require that participants be “reinformed” and that a new consent form containing the updated information be discussed and signed. Sponsors are also responsible for selecting monitors to oversee the progress of an investigation and report to the sponsor their findings regarding investigator compliance with the protocol, reporting of adverse events, and the proper consent of subjects. Currently, this information is shared only with the sponsor and the investigator, but the material could provide valuable information to a local or central Research ERB regarding study conduct.18 Thus, sharing these reports with boards could improve their ability to protect research participants.

As discussed, DSMB/DMCs typically are established to provide a mechanism for looking at unblinded safety and efficacy data on an interim basis (while the study is ongoing) and determining whether it is appropriate to continue the study, a determination that is often driven by risk-benefit considerations. Currently, typically little or no communication occurs between DSMB/DMCs and IRBs because they are generally constituted under different premises (sponsor versus institution).

There is a similar lack of communication to IRBs regarding findings com-

piled for sponsors and regulatory agencies. Such findings would include monitoring reports submitted to sponsors about investigator compliance, closed session reports by the DSMB/DMC, or observations issued to an investigator in a form FDA 483 or a Letter of Determination issued by OHRP.

Monitoring reports that are currently performed for the sponsor are not routinely shared with the IRB. Yet, monitoring visits performed on behalf of the sponsor are usually the only real-time oversight activities that are conducted at the site, and they would be extremely useful for ethics review purposes. Violations in ethical conduct and/or noncompliance with regulations would require immediate action and remedy by the investigator.

A likely result of direct DSMB/DMC-Research ERB communication could be increased participant protection as a function of increased and timelier attention to risk-benefit analysis under unblinded conditions. However, it should be noted that the DSMB/DMC is a “protected body” that is able to look at unblinded data at a point at which no one else can. Premature disclosure of data and findings can in fact invalidate an entire study, and diligent care should be taken to ensure that this is avoided.

DATA SECURITY: PROTECTING CONFIDENTIALITY

All research with identifiable research participants involves issues related to the protection of confidentiality and privacy. Just as the protection program should monitor studies to ensure that risks are minimized and participant safety is assured, it also should take precautions to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants during and after the study. (The Committee on National Statistics/Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences and Education panel makes a number of recommendations regarding confidentiality in Appendix B.) In some cases, invasion of privacy or breeches of confidentiality might be the only research-related risks for participants (NBAC, 2001b). Current regulations regarding privacy require that IRBs only approve a study if “adequate” provisions are made to protect privacy and maintain confidentiality. Recent legislation, specifically the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA),19 includes some provisions for protecting privacy in the research context, but is limited in its reach. Recent activities in the realm of privacy protection in the research context are described below.

Privacy and Confidentiality Provisions

New regulations provide increased protection for medical records being sought for research purposes in circumstances in which it may not be

feasible to obtain authorization from patients. Under HIPAA,20 access to medical records that was once taken for granted will be more difficult to obtain. Research organizations and Research ERBs need to review their policies regarding exempt review in light of these regulations because they will affect organizational practices concerning the waiver of the requirement for informed consent and the need for ethics review. The regulations codify privacy standards throughout the United States and will have an effect on medical and behavioral research (see Chapter 7).

Food and Drug Administration Special Requirements for Management of Electronic Data in Clinical Trials

In March 1997, FDA issued a Final Rule addressing requirements for using electronic records and signatures.21 The regulation applies to a broad array of records and activities in the clinical trial setting used to support FDA product review and approval. The new ruling applies to all FDA-required records, including those generated during a clinical trial.

It is the sponsor’s responsibility to ensure that a computerized system design complies with federal regulations and is validated by qualified information technology personnel. In addition, the sponsor should provide appropriate training and tools to research personnel at the clinical site involved with the collection, correction, and transmission of data electronically. If an investigator at an institution is sponsoring research subject to 21 CFR 11 and utilizing computer systems under the jurisdiction of the research organization, then the research organization should assure that systems design, validation, and training comply with these regulations.

SUMMARY

The collection and assessment of information about participant safety and data integrity while a trial is ongoing is an essential component of any protection program. Thus, a DSMP is essential for research that has the potential for more than minimal risk. The intensity of monitoring beyond the DSMP should also be scaled to a study’s particular level of risk; this focusing of resources will help ensure that more HRPPP attention can be directed to studies that pose the greatest risks to participant safety.

Research organizations should explore their own monitoring activities and guidelines at the institutional level. To facilitate this examination, OHRP should provide guidance and educational opportunities. In addition,

federal agencies should harmonize their guidelines about safety monitoring at various risk levels and share information with the research community and the public regarding the results of federalwide monitoring. High-risk NIH studies (intramural or extramural) should be monitored with the same scrutiny as FDA-regulated trials, and for certain high-risk studies, DSMB/ DMCs are essential. NIH should therefore take the lead in developing and funding more DSMB/DMCs. Federal agencies also need to standardize their adverse event definitions and reporting requirements so that these reports can be more effectively used by Research ERBs to ensure participant safety.

To protect research participants as fully as possible, it is essential that the relevant program mechanisms communicate with one another effectively. To this end, the DSMB/DMC should advise the Research ERB regarding whether new information affects participant safety and, as appropriate, this information should in turn be communicated to participants.