2

A Systemic Approach to Human Research Participant Protection Programs

The current system for protecting research participants is based on established ethical principles and federal regulations that grew out of a research context consisting largely of single investigators at single institutions developing, conducting, and publishing the results of original research. Today’s research environment is far more complex and requires a more multifaceted and interconnected system of protections. To sustain the current level of research, the protections that are thought to be essential should be reviewed and a more responsive and flexible organizational structure that will better assure that the necessary protections are in place should be created.

This chapter describes what the committee has termed a “Human Research Participant Protection Program” (HRPPP), also called throughout this report a “program” or a “protection program,” and introduces the protection functions intrinsic to its overarching framework. Subsequent chapters elaborate the specific mechanisms and accountability provisions needed to carry out program functions.

THE NEED FOR A SYSTEMIC APPROACH

In envisioning such a protection program, the committee attempted to examine the perspective of the individual who volunteers to participate in a research study. This individual might be a healthy volunteer, might have a specific disease or condition, or might be a participant in a sample survey. The focus the committee adopted in devising the program is best repre-

sented by the following question—“What protections would a potential participant want in place before and after he or she has consented to be a part of a study?” Based on testimony from research participants and their families (Cohen, 2001; Gonsalvez, 2001; Pedrazzani, 2001; Terry, 2001; Wayne, 2001) and the committee members’ own experiences as research participants, investigators, and research administrators, the committee believes that the goals of an effective program are to ensure that

-

Participant welfare is of central concern to the investigator(s) and staff and that researchers take steps to minimize the level of harm to which participants may be exposed and treat participants with respect and dignity throughout the study.

-

The investigator(s) who designed the study, those who will collect the data, and others who interact with participants are appropriately trained and well qualified to conduct research with humans and to perform all study procedures.

-

The investigator(s) who designed the study, those who will collect the data, and those who oversee the research have no financial or other conflicts of interest that could bias the study or negatively affect participant care, and unavoidable potential for conflict has been disclosed to participants before enrollment and adequately managed throughout the study.

-

The proposed study has been reviewed by neutral scientific experts to ensure that the question(s) asked are important; that the protocol is feasible, well designed, and likely to result in an answer(s) to the research question(s); that the risks have been minimized and do not outweigh the benefits (even if the participants will not directly benefit); and that participants are given all the information necessary to make an informed decision1 about participation in language they can understand.

-

An advocate or friend can help explain the details of the study to participants if necessary or desired.

-

Participants understand that they are free to refuse to participate or to withdraw from the study without fear of retribution or loss of benefits to which they are otherwise entitled.

-

The investigator(s) or a central coordinator will monitor the progress of longitudinal studies, and if new information pertinent to the protocol becomes available during the study that might be important to participants, the research team will share it with participants and adjust their individual involvement as appropriate (similarly, if the risks are greater than first believed or if the intervention is found to be successful earlier than predicted, the study might be stopped by the central coordinator).

-

Provisions are in place to cover the cost of participants’ medical and rehabilitation services should they experience an adverse event related to the research.

-

The data analysis is of high quality and free from bias, and study findings are reported to the scientific community and study participants, regardless of the outcome.

Recommendation 2.1: Adequate protection of participants requires that all human research be subject to a responsible Human Research Participant Protection Program (HRPPP) under federal oversight. Federal law should require every organization sponsoring or conducting research with humans to assure that all of the necessary functions of an HRPPP are carried out and should also require every individual conducting research with humans to be acting under the authority of an established HRPPP.

In its 2001 report, Ethical and Policy Issues in Research Involving Human Participants, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) states that “Federal policy should cover research involving human participants that entails systematic collection or analysis of data with the intent to generate new knowledge” (2001b, p.40). The committee agrees with NBAC that research protections should extend to the entire private sector, as a responsible system of protections should be afforded to all who volunteer to participate in research, regardless of sponsor or location. Therefore, a first and essential step in improving the current system of protections is to require that it be in place universally.2

Congress should extend federal regulatory jurisdiction to all research, whoever sponsors or conducts it. Although a number of mechanisms might be used to bring privately sponsored and conducted research within the constitutional reach of the federal government, one approach could be to extend jurisdiction to all providers or entities that receive federal funds for health care, education, or any other relevant activity. In the meantime, until federal authority is extended, state legislatures have the authority to regu-

late research conducted within their borders that has not been regulated by the federal government. To avoid confusion, the committee encourages the states to do so in a manner that is consistent with the existing federal regulations and with the recommendations and approach offered in this report. The Maryland statute adopted in 2002 provides one such model for this approach (An Act Concerning Human Subject Research—Institutional Review Boards. House Bill 917. General Assembly of Maryland. 2002).3

DEFINING PROTECTION PROGRAMS

Appropriate protection that incorporates the necessary safeguards can most effectively be provided through a program of systematic and complementary functions within which discrete roles and respective accountability are clearly articulated. By definition, “a system is a set of interdependent elements interacting to achieve a common aim…” (Reason, 1990). The critical factor in the effectiveness of any given system lies in how the discrete elements are brought together to achieve their common aim (IOM, 2001b)—in this context, the protection of research participants. Therefore, the form the program assumes is less important than the functions it performs. However, each entity that conducts human research should have a defined set of processes and procedures that are appropriate to its research portfolio. In some cases, this may involve the utilization of an independent IRB or Contract Research Organization, while in other cases, all oversight activities would be performed by “in-house” entities. Regardless of the specific program configurations, the system should be developed to maximize participant protection and minimize unproductive administrative activities and excessive costs.

In its first report, Preserving Public Trust: Accreditation and Human Research Participant Protection Programs (IOM, 2001a), the committee adopted the term “HRPPP” to embrace a set of functions somewhat broader than is represented in the customary emphasis on the Institutional Review Board (IRB). In that report, the key components of the program were defined as follows:

-

the participants involved in the research;

-

the investigators carrying out the research;

-

the review boards responsible for reviewing the scientific and ethical integrity of the research;

-

the organizational units (which may include the investigator) responsible for designing, overseeing, and conducting the research and analyzing data and reporting study results; and

-

the monitoring bodies, including Data and Safety Monitoring Boards/Data Monitoring Committees (DSMB/DMCs),4 ombudsman programs, and data collection centers.

The program’s most basic function is to develop and implement policies and practices that ensure the adequate protection of research participants. Because the conduct of human research has expanded to diverse settings—including the public and private sectors, academic centers, and community clinics, as well as unisite, multisite, and international sites—the requirements of the system for protection should be universal and should adhere to a basic set of principles that encompass the items outlined above.

Box 2.1 includes several examples of such policies from a range of research contexts. The diligent application of program policies and practices will ensure that participants in any research project are protected against undue risk, that they provide informed consent to participate, and that all efforts are made to ensure that the rights, privileges, and privacy of participants are protected throughout the study, the subsequent analyses of collected data, and the dissemination of study results.

Four basic functions are intrinsic to any program, regardless of research setting or sponsor:

-

comprehensive review of protocols (including scientific, financial conflict of interest, and ethical reviews),

-

ethically sound participant-investigator interactions,

-

ongoing (and risk-appropriate) safety monitoring, and

-

quality improvement (QI) and compliance activities.

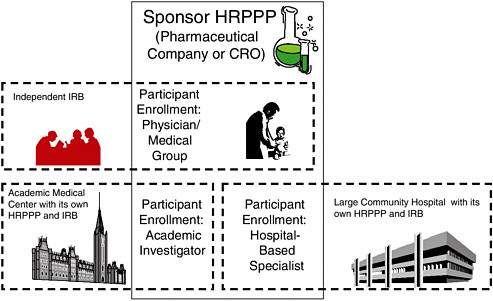

The precise structure of a program will vary from organization to organization and from protocol to protocol. In fact, the program may be most appropriately conceptualized as a modular framework assembled to meet the participant protection needs intrinsic to a particular protocol. An illustration of such a framework that might be assembled for a clinical trial is depicted in Figure 2.1. In this case, the collective HRPPP includes modules and activities within several individual HRPPPs. The elements of these

|

Box 2.1 International or National HRPPP: The set of policies and practices dictated by legislation and regulation (e.g., 45 CFR 46, 21 CFR 50 and 56, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice [GCP]) and enforced by governmental authorities (e.g., Office for Human Research Protections [OHRP], the Food and Drug Administration [FDA], the National Institutes of Health [NIH]) or recommended by international bodies (e.g., International Conference on Harmonisation, for drug trials). Academic HRPPP: The set of policies and practices existing at a particular research institution, consistent with regulations, guidelines, and other applicable standards but enhanced with local laws and/or research-specific considerations and community-specific input. Industry HRPPP: The set of policies and practices existing at a particular industrial organization, consistent with GCP or other applicable standards but enhanced with local and/or research-specific considerations. Collaborative HRPPP: The set of policies and practices existing at particular research institutions and industrial firms engaged in collaborative research (e.g., multicenter trials), consistent with GCP or other applicable standards but enhanced with considerations applicable to the collaborative research. In most cases, the sponsor HRPPP would retain ultimate accountability for the conduct and oversight of the study; however, various functions may be contracted out to other appropriate entities (such as contract research organizations or academic institutions) with the necessary assurances. |

individual HRPPPs come together to form the system responsible for carrying out all necessary protection functions for a particular protocol. Despite this flexibility, however, it is essential that all basic protection functions be met—although various organizations, depending on their missions and activities, might utilize different individuals, offices, or authorities to exercise each function.

For example, in some research universities a separate office might manage all issues related to financial conflicts of interest, while a smaller research institution might address those issues through the Office of General Counsel (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). In most instances, who ensures that certain functions are being addressed matters less than the fact that responsibility and accountability are clearly defined for each function and that each unit of the protection program understands the system and its role within it. Thus, although systems-based protection programs could take many forms, currently, it is likely that a significant portion of them

FIGURE 2.1 A Schematic Illustration of Roles and Interactions of HRPPPs in a Typical, Multisite Clinical Trial

Multiple HRPPP modules often collaborate to form the HRPPP for a specific protocol. In this situation, the sponsor’s HRPPP is ultimately accountable for the entire trial. For participants enrolled by the community physicians, the sponsor’s HRPPP bears direct responsibility for all of the protection functions except the protocol ethics review conducted by the independent IRB under contract with the sponsor. For participants enrolled by the academic investigator and the hospital specialist, it is likely that the sponsor will contract, respectively, with the academic medical center and the community hospital to carry out many (though perhaps not all—data and safety monitoring may be retained, for example) of the protection functions, including science and ethical review (which may be ceded to a lead IRB); education of investigators, board members, participants, etc.; conflict of interest review; and quality improvement for their portions of the study.

employ a set of processes conducted by IRBs and a few other entities within an organization—e.g., regulatory compliance.

The committee acknowledges that the research process itself is a complex and adaptive one and that efforts to integrate an additional complex system within it will be challenging and could create bureaucratic and administrative distractions rather than contribute value and enhance performance. However, the committee has concluded that appropriate participant protection can best be assured through a systemic approach that utilizes diversified and distributed elements with clearly defined and articulated responsibilities. A similar systems-based approach to ensuring patient safety has been recommended by panels that have examined the quality of health

care (IOM, 2000b, 2001b). Minimizing duplication, role confusion, and red tape among the varied program components will be critical to the success of the committee’s proposed reconfiguration of the existing approach to participant protection. Thus, the coordination of protection functions requires deliberate attention if we are to surmount the current difficulties that confront us as we work to achieve a performance-based system.

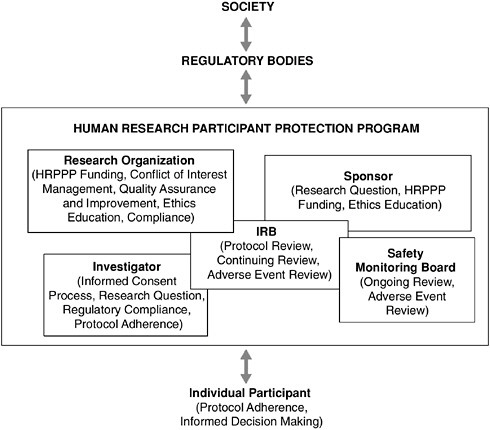

ESTABLISHING A BALANCED PROGRAM

Research is a societal enterprise, with the responsibility for the strength and appropriateness of the endeavor transcending the various layers of involvement in the process. As depicted in Figure 2.2, a stream of accountability begins with the individual research participant agreeing to enroll in a study and follow its protocol and runs through the HRPPP (including the investigator, the research organization, the oversight bodies, and the sponsor), to the federal agencies charged by our elected officials with overseeing the research enterprise. It is important that the respective responsibilities at each level are reflected in the composition of any individual HRPPP, and to ensure the optimum performance of protection programs, the perspectives of the various stakeholders should be effectively balanced. Although formal operating and communication procedures are essential to achieving such balance, the establishment by program leadership of an ethically sound research culture throughout the program is critical to ensuring the comprehensive protection of research participants.

Necessary Conditions for a Sound Protection Program

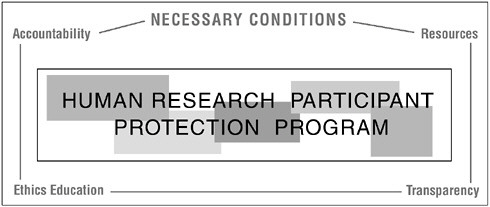

As illustrated in Figure 2.3, the prerequisite conditions of any protection program are

-

accountability—to assure the quality and performance of the protection program,

-

adequate resources—to assure that sufficiently robust protection activities are in place,

-

ethics education programs—to provide research personnel and oversight committees with the knowledge necessary to carry out their obligation to conduct or oversee ethically sound research, and

-

transparency—to ensure open communication and interaction with the local community, research participants, investigators, and other stakeholders in the research enterprise.

Each organization involved in research should ensure that these conditions are met for studies conducted under its purview in a manner that is

FIGURE 2.2 Accountability for Human Research Activities

Responsibility for the protection of research participants and the quality of the human research enterprise is shared among all those involved. Individuals considering participation in a research study should do so carefully and with regard to the responsibilities entailed. Human Research Participant Protection Programs (HRPPPs) have a direct responsibility for the safety of those enrolled in studies carried out under their purview. Regulatory bodies should provide HRPPPs with cogent guidance and able leadership, and society should ensure that regulatory bodies have the tools necessary to oversee and guide the national protection system. Owing to the modular nature of HRPPPs, the specific relationships that track participant protection duties within a protection program may vary from project to project. However, this flexibility does not alleviate the absolute obligation of all parties to ensure adequate safeguards are in place for every research participant.

FIGURE 2.3 Effective Human Research Participant Protection Programs Require Four Necessary Conditions

In order to establish and operate a sufficiently robust Human Research Participant Protection Program (HRPPP), four necessary conditions should be pervasive throughout a research culture. These conditions include accountability for all participant protection activities; sufficient resources to carry out those activities (monetary and non-monetary); ethics education programs for those who conduct and those who oversee research with humans; and transparency, in terms of open communication with the public and other stakeholders regarding HRPPP policies and procedures.

tailored to its mission, the breadth and substance of its research program, and the specific context of its community.

Accountability

Recommendation 2.2: The authority and responsibility for research participant protections should reside within the highest level of the research organization. Leaders of public and private research organizations should establish a culture of research excellence that is pervasive and that includes clear lines of authority and responsibility for participant protection.

Administrative responsibility for the program may reside within a designated office of the organization (perhaps called “Office for the Protection of Research Participants”), but ultimate responsibility for the adequacy of the program resides at the highest level of the research organization. In private organizations, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is ultimately responsible for participant protection; in an institutional academic setting,

the responsibility lies with the president. Authority for implementing the protection program could be delegated to others within the organization or institution, such as a vice president or a dean, but final accountability for the program’s mission, goals, and success (or failure) resides with the CEO or president.

Some elements of the HRPPP may reside within the same research organization or they may be external entities with which the sponsor or the research organization has contracted. Whatever the structure, mechanisms should be in place to assure that appropriate integration of the different elements occurs. For example, financial conflict of interest issues may be subsumed in a more general institutional policy on conflict of interest, but such determinations relevant to research involving humans should be made available to the IRBs reviewing the research in order to be included in the comprehensive ethical review of the study. Lack of coordination and communication within a program leads to duplication of effort that can result in a significant loss of time and resources. Most significantly, lack of communication diminishes a program’s capacity to protect research participants.

When multiple organizations are involved in the research, at least one organization should have primary responsibility for obtaining appropriate and documented assurances from the other participating organizations. In the case of a university and a pharmaceutical firm, for example, the firm would be responsible for meeting FDA sponsor regulations (including safety monitoring) and for choosing qualified investigators and site(s) where an institutional protection program was in place. The university would be responsible for ensuring that the investigators conducting the research at their facilities are appropriately trained in GCP or other relevant standards, that the study is scientifically sound, that the study’s potential benefit outweighs the potential risks, and that the participants are properly informed about these potential risks. The university would also be responsible for complying with all applicable federal, state, or local regulations. In a multisite project, each site could designate its own IRB as the responsible oversight body, or several sites could designate one of the IRBs as the primary IRB (see Chapter 3).

The organization with primary responsibility for obtaining the assurances should also be responsible for acting decisively should violations occur. Such actions could include termination of the study or the site and/or reporting violations and violators to relevant authorities. However, it should not be assumed, for example, that an industry sponsor participating in FDA-regulated trials has sole responsibility for the protection program. Participants are best protected if all organizations and individuals involved share equally in that responsibility, particularly because research organizations and investigators are more directly and closely involved with the research participants than would be a remote sponsor.

One committee suggestion for ensuring that accountability within any approved human research study is clearly articulated is the use of a document that explicitly defines the roles and responsibilities of all relevant parties at various stages of a protocol’s development. Such a document could be very useful to the IRB and others in the program as a tool for confirming that the necessary protection elements are in place within an HRPPP for a specific protocol. One template that could be adapted to address the protection needs within individual protocols is presented in Appendix C, along with several case scenarios developed to illustrate how this template might be used to establish protocol-specific accountability plans.

Within an organization such as an academic institution, the roles and responsibilities would likely remain the same for most single-site investigator-initiated trials, with the specific protection-related tasks determined by the degree of risk posed and protocol methodology. In contrast, the roles and responsibilities in large multicenter trials involving both private industry and academic institutions may vary widely from study to study. Again, the composition of the program for any protocol may be distributed among different elements or organizations as long as all parties clearly understand and meet their respective protection obligations.

A key to assuring accountability throughout the conduct of human research is efficient and frequent communication among all components of the protection program. This process is particularly critical when program components are geographically dispersed (i.e., multisite studies). HRPPPs will benefit from improved electronic linkages that will expedite communication and facilitate a “seamless” system of protections. For example, an electronic version of the template presented in Appendix C could be used to track the completion of tasks by each component of the HRPPP for a particular research study.

Two fundamental assumptions should underlie the interactions among program elements: 1) sound research is necessary for improvement of the human condition and 2) all research must be conducted in an ethical manner. Communication between the organizations sponsoring, reviewing, and conducting human research and the overseeing regulatory agencies provides the primary framework within which protections are provided.5 Thus, programs should establish mechanisms for ensuring that effective communication occurs between all entities. Just as individual program components are accountable to the senior leadership of research organizations, the overall program is accountable to the appropriate federal oversight office(s). Based upon their research portfolios, educational institutions may be ac-

countable to several federal agencies, while commercial enterprises may be primarily accountable to FDA. Accreditation by one of the independent accrediting agencies, presuming that accreditation is found to be effective, may provide assurance that the organization is achieving a particular level of protection. However, the goal of any organization should be an ongoing commitment to improve participant protections, not simply to comply with regulations. As stated in the committee’s first report, regulatory compliance should be the floor below which organizations do not fall; in no way should it represent the ceiling (IOM, 2001a).

Resources

Recommendation 2.3: Research sponsors and research organizations— public and private—should provide the necessary financial support to meet their joint obligation to ensure that Human Research Participant Protection Programs have adequate resources to provide robust protection to research participants.

No research study involving human participants should be allowed to proceed without ensuring adequate financial support for the proper functioning of the relevant HRPPPs. Providing the resources needed to establish and maintain the infrastructure for a robust protection program is the joint responsibility of the institution (or other organization) conducting the research and the research sponsor. Necessary resources for the HRPPP would include adequate space, equipment, and personnel, as well as a sufficient annual budget.

Assumption of the responsibility to pay for participant protection has been an issue of dispute within the funder/researcher alliance for some time. Although both sponsors and investigators agree that funds must be allocated to pay investigators and staff and to cover the out-of-pocket costs of research,6 no satisfactory agreement has been reached regarding how the increasing costs of protecting participants should be distributed. Not surprisingly, and as the recent tragedies and citations for administrative infractions at various academic medical centers demonstrate, the responsibility for protecting research participants ostensibly was not sufficiently funded at otherwise prestigious institutions (OHRP, 2000, 2001; Zieve, 2002). Agreements with OHRP that permitted the centers in question to continue federally funded research required significant increases in institutional support, in terms of both finances and personnel (McNeilly and Carome, 2001; NBAC, 2001b).

For example, one seriously overlooked cost in providing participant protection is that of providing the highly skilled professionals who are required to staff, manage, and serve on IRBs the time necessary to perform their duties, and monetary compensation for their services. Evaluation of protocols requires a variety of skills and knowledge, ranging from technical scientific design expertise to a strong working knowledge of the ethical literature. Both senior staff and IRB members should be familiar with the potential participant communities that will be enrolled and affected by a particular study. Even assuming that an individual—or a collection of individuals— possesses the needed skills, a rigorous and thoughtful review of protocols will still be time consuming. In most academic settings, unfortunately, the time needed to participate in dedicated IRB service is not provided.

To help address these issues, IRB membership should be viewed as an institutional obligation, and those who serve on IRBs should receive release time from other job responsibilities without financial or academic penalty (similar to that provided for jury duty). Ideally, such coverage might also be extended to community representatives who serve on IRBs. At a minimum, research organizations should provide such allowances to their faculty members so that they have more time to participate in dedicated IRB efforts.

Few data have been published that quantify the costs of ethics review, making it difficult to determine reasonable compensation for offices or individuals involved in the process (NBAC, 2001b; Wagner, unpublished data).7 The committee once again stresses the need for data collection and applauds the efforts now under way by the Consortium to Examine Clinical Research Ethics at Duke University to systematically begin addressing this task (Duke University, 2002).

One existing model that might be instructive in estimating costs are for-profit and not-for-profit independent fee-for-service IRBs; their fee structure can provide some notion of what the private sector now pays for protocol review. Although the committee acknowledges that academic and nonacademic boards operate under different frameworks, because both must accomplish the same mandated tasks, some comparability exists.

In general, research is funded by NIH, the National Science Foundation, or other federal agencies, private foundations, or industry. The private sector generally pays for its initial and ongoing IRB review explicitly, and other sponsors should do so as well.

The committee anticipates that some government agencies will argue that the funds for obtaining ethical review of individual protocols are pro-

vided through the indirect rate attached to the direct costs of research. Due to the infrastructure nature of HRPPP activities, officials claim that they have already paid for this review, as it is a cost that transcends individual projects. However, not all research projects involve humans, and even in the case of human research, the extent of the review and ongoing monitoring will vary widely according to the risks presented by a specific protocol. Consequently, the costs per project are discrete.

In response to this argument regarding indirect cost recovery, academic institutions counter that the limited overhead funds available for facilities and administrative costs must be used to meet a number of competing needs. This is especially challenging for academic medical centers in the current era of managed care, in which payments for patient care have markedly diminished, restricting their ability to subsidize research programs at past levels. However, the committee asserts that because sufficient resources are fundamental to implementing a robust participant protection program, providing the needed funds is a real cost of doing research.

Private foundations, which frequently provide much lower indirect costs than federal grants, should also provide money for HRPPP review within their yearly project budgets. Ethics review of investigator-initiated protocols that receive only internal funding should be paid for by the academic department or the institution supporting the research. If an organization cannot provide the resources for the protections, it should not conduct the research.

Payment schemes can be determined by attempting to calculate the actual cost of the time and effort involved in the review process or by agreeing to a fixed percentage of directly expended research dollars. In either event, a robust quality assurance process should determine whether the amounts committed are sufficient to accomplish the required tasks (see Chapter 6). Institutional funding might come from a variety of sources. IRBs could charge for their services, as many already do (IRB teleconference8). Overhead funds allocated through industry grants and federal indirect costs could include a specific percentage designated for such activities.

The committee commends NIH for beginning to address this fundamental need through its Request for Applications to support one-time infrastructure building activities and its ongoing grant mechanisms in research ethics, informed consent, and clinical research education programs (NIH, 2001; NIH, 2002b,c). This most recent initiative is soliciting creative solutions to improve HRPPP infrastructure, such as better methods for ongoing monitoring of adverse events or better software systems for tracking clinical trials within a program, that will benefit protection efforts across the

|

8 |

See Appendix A, “Methods,” for more information. |

country. Unfortunately, this particular mechanism does not provide for ongoing support to stabilize the enhanced operations of most programs. The committee encourages NIH and other research sponsors to continue working with research institutions to bridge the gap between resource needs and the availability of funding mechanisms to meet them.

Ethics Education

Recommendation 2.4: Research organizations should ensure that investigators, Institutional Review Board members, and other individuals substantively involved in research with humans are adequately educated to perform their respective duties. The Office for Human Research Protections, with input from a variety of scholars in science and ethics, should coordinate the development and dissemination of core education elements and practices for human research ethics among those conducting and overseeing research.

Education regarding the research process and the ethical issues intrinsic to research involving human participants is essential at every level of accountability in the program. Investigators, key research personnel, IRB members, and institutional officials should all possess a core body of knowledge relating to the ethical design and conduct of a research protocol.

The research organization is responsible for ensuring that program personnel are educated about their responsibilities and proper conduct. The research sponsor also shares responsibility for ensuring that a research organization has the qualified personnel and resources needed to carry out a study—and the adequate education of personnel is part of this responsibility. If an investigator is not part of an institution, the sponsors themselves must provide sufficient education in order to enlist an investigator in a particular project. For example, CROs enlisting private practice clinicians to carry out a study should ensure that they are appropriately trained in ethical research practice, good clinical practices, and the specific protocol (Wyn Davies, 2001). Therefore, both entities must provide adequate resources for initial and continuing education.

One-time education modules do not ensure that these individuals fully appreciate the complex issues involved in human research. Education and consultative services should be ongoing in order to create a rich culture of ethical research. Continuing education options might include activities at annual professional meetings focused on various aspects of ethical research design and conduct, tuition reimbursement for participation in formal education courses, formal mentoring programs to facilitate the training of new investigators, “brown bag” sessions on particularly complex topics or new information, seminars, Web-based tutorials, or in-house research consulta-

tion services. Because of the many competing demands on all parties involved (i.e., those developing the protocols as well as those reviewing them), these educational programs should be efficient as well as effective.

It should be noted, however, that the effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education programs has been in question (Davis, et al., 1995; Davis and Taylor-Vaisey, 1997; Thomson O’Brien, et al, 2002), and that although education is important, other program elements also are essential in ensuring that participants are protected and research is conducted ethically. Ideally, the cumulative effect of a comprehensive education program and the inculcation of an ethically sound research culture will enhance the performance of all parties involved in human research, thereby improving the protection participants receive.

An evolving core body of knowledge and best practices that focuses on ethical considerations, contextual concepts and issues, applicable regulations, and case law should be established. OHRP, in consultation with other federal agencies, should pursue efforts to facilitate the development and dissemination of this knowledge and best practices. The pertinent content for education programs at the various levels of the HRPPP is discussed below.

Organizational Leadership. Consistent with Recommendation 2.2 regarding ultimate accountability for human research protections, those within the administrative structure who have oversight responsibility for program functions should be knowledgeable about the ethical tenets underlying an effective program. Box 2.2 describes the type of information that those who oversee program activities should have and suggests that appropriate professional organizations work together to develop the relevant curriculum.

Investigators. Research investigations that enroll participants require a specialized knowledge base that goes beyond that provided through traditional scientific training. Research investigators and key personnel should be versed in the ethical foundations underlying research participant protection, the regulatory requirements for carrying out such research (including confidentiality issues), the relevant research administration and management skills (Phelps, 2001), and, as applicable, GCP and medical ethics. Failure to understand the complexities of conducting research with humans may lead to serious errors in the implementation of a study that would compromise the safety of the participant(s) and/or the integrity of the data and its subsequent interpretation, possibly exposing participants to unnecessary risks, however minimal the risks may have been.

Until recently, few research investigators have received formal education in the human participant protection issues underlying the theory, de-

|

Box 2.2 President, Chancellor or CEO: The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), in concert with Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research (PRIM&R) and the Applied Research Ethics National Association (ARENA) should develop educational materials and programs for executive leadership positions in private industry and academic institutions. These could include knowledge of the federal regulatory structure, especially the assurance process; an overview of the federal regulations governing human research; the definition and function of each component of a program; an overview of the program accreditation process and specific knowledge of the accreditation standards at the level of the institution; continuing education on evolving issues in human participant protections. Dean for Research or Industry Counterpart: AAMC and PhRMA, in concert with PRIM&R and ARENA should develop educational materials and programs for Deans, Vice Presidents, and Department Chairs. These would include knowledge of the federal regulatory structure, especially the assurance process; an overview of the federal regulations governing human research; the definition and function of each component of a program; an overview of the program accreditation process and specific knowledge of the accreditation standards for the institution; continuing education on evolving issues in participant protections. Federal Research Assurance Signatory: In-depth knowledge of the federal regulatory structure, especially the assurance process; an overview of the federal regulations governing human research; the definition and function of each component of a program; an overview of the program accreditation process and specific knowledge of accreditation standards at all levels; continuing education on evolving issues in participant protections. Institutional Compliance Officer: In-depth knowledge of the federal regulatory structure, especially the assurance process; an overview of the federal regulations governing human research; an understanding of the certification process for IRB professionals and investigators; the definition and function of each component of a program; an overview of the program accreditation process and specific knowledge of accreditation standards at all levels; continuing education on evolving issues in participant protections. Academic or Unit Department Head/Scientific Merit Signatory: Certification as an investigator; overview of the federal regulatory structure and assurance process; overview of federal regulations governing human research; knowledge of professional codes of research ethics and conduct such as the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki; a working knowledge of the IRB process of ethics review; in-depth knowledge of the review process for scientific merit; specific knowledge of program accreditation standards for investigators; review of accreditation standards for other program components; continuing education on evolving issues in participant protections.

|

sign, or conduct of biomedical or behavioral studies (NBAC, 2001b). This standard is not acceptable, as researchers should have a strong working knowledge of these topics. The committee believes that as individual researchers increase their understanding of the ethical principles and the regulations (state and federal) that govern research, and their intent, they are more likely to comply with them.

IRB Members and Staff. The specialized education requirements for IRB members are even more substantial than those for investigators, yet as a group, IRB members are similarly undereducated. A 1995 survey of 186 IRBs at major universities found that almost half provided no training or less than an hour of training to IRB members (Hayes et al., 1995). Although research institutions and IRBs increasingly recognize the need for training, and the ARENA certification program has resulted in more trained IRB professionals, the extent to which such training occurs nationwide and the effectiveness of such programs remain unclear (NBAC, 2001b).

IRB members are responsible for the comprehensive review, safety assessment, and continuing monitoring activities of protocols, and uniquely within the research organization, for considering the participant advocacy perspective in protocols. In some cases, individuals serving on the board are providing a nonscientific, community perspective in the protocol review process and are likely to need a general knowledge of the research process to facilitate their IRB activities.9 To be effective, IRB members should understand the ethics and history of research with humans, the current structure and funding of research projects, and the regulatory structure of research, including local laws (see Chapter 3 for an elaboration of IRB education needs). In addition, IRB members should be able to read scientific literature and protocols at some level, understand scientific methods for various disciplines, assess the impact of the research on the community and vulnerable populations within it, conduct a risk-benefit analysis for the proposed protocols, and appreciate and enforce the principles of informed consent. The committee does not expect that every IRB member will possess all the requisite expertise, but rather that as a group the full complement of knowledge is provided within the IRB and that individuals maintain a basic appreciation for all issues. IRB professional staff should have similar knowledge to facilitate the effective operation of the board and to support members, investigators, and organizations in their respective roles. The organizations of Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research and

ARENA should be encouraged to continue developing their education tools for IRB members and staff.

Research Participants. An even more underserved partner in this process is the research participant. Research participants should have a general understanding of the research process in terms of how ideas are generated and decisions are made. At the very least, participants should know that they are able to ask questions about their potential participation and the types of questions to consider in their decision making process regarding participation (see Chapter 4).

Recently, two guides directed at potential research participants have been published (ECRI, 2002; Getz and Borfitz, 2002). These documents include explanations of the clinical trial process and the phases of research, factors to consider and questions to ask before participating, what a participant should expect from study staff, how to evaluate the consent form and the participant’s consent obligations, the potential costs of participating in research, what do to if things go wrong, and how to find and enter clinical trials.

Transparency

Recommendation 2.5: Human Research Participant Protection Programs should foster communication with the general public, research participants, and research staff to assure that the protection process is open and accessible to all interested parties.

The system of protections established by any HRPPP should be transparent and open to the public. Yet, recent press reports have described IRB activities as closed and “insulated from public accountability” (Wilson and Heath, 2001d). If research institutions, federal agencies, and private companies seek to maintain the trust of those in the community and continue to ask individuals to participate in research studies, the mechanisms used to protect participants from undue harm and to respect their rights and welfare must be apparent to everyone involved. This transparency requires communication among all parties to ensure that current or prospective research participants can question the mechanisms used to develop, review, and implement research protocols.

Program transparency can be achieved by providing graded levels of information and guidance to interested parties. At the first level, the general public should have access to information about how the local programs operate. All protection programs (both private and public) should provide basic information regarding the principles of human research protection and the structure and functions of their own programs. In some cases, it

may be useful to provide the names of individuals responsible for carrying out particular program functions. This general information should be available upon request as pamphlets or through Web-based media with links to relevant federal Web sites. Beyond general program information, IRBs in particular are increasingly likely to be held publicly accountable for their actions. A recent Maryland law begins to move in this direction by requiring that copies of IRB minutes, redacted to remove confidential information, be made available within 30 days of being requested (An Act Concerning Human Subject Research—Institutional Review Boards. House Bill 917. General Assembly of Maryland. 2002). It may also be helpful to provide general contact information for individuals interested in future research participation. Public education is a key component in the promotion of transparency and the sustenance of public trust in the research process.

At the second level, prospective research participants should be provided access to detailed, project-specific information, which may include more information about the overall protection process and relevant financial conflict of interest information regarding the investigators or institution. For example, prospective participants may want assurances that indemnification means that they will not pay out-of-pocket expenses, or they may want additional explanation of general conflict of interest information disclosed to them through the informed consent process. This type of study-specific information should be readily available upon request, either through a secure Web site or a neutral third party within the program who can answer specific questions.

A third level of communication should be available to participants who are enrolled in an ongoing research protocol. Programs should make available a responsible, knowledgeable neutral third party to whom participants (or their families) can bring any questions or concerns regarding their experience in the study or with any member of the research team or institution. This individual should also be available to those involved in the research process who are not participants, such as investigators, co-investigators, or support staff and should be available to provide guidance regarding the appropriate channels for voicing concerns and the actions that will be undertaken to further evaluate and/or address a particular situation. Research participants, and every individual involved with the conduct of human research, should feel confident that their concerns will be taken seriously and that the program has an established and efficient mechanism for addressing them. In addition to an ongoing mechanism to hear stakeholder concerns, it may also be useful to establish a more structured forum through which participants have the opportunity to provide feedback to the protection program. For instance, a “Research Day” event in which past and current participants are invited to share concerns or complaints about their research experience can provide a proactive means to gain valuable input

into program operations as well as an opportunity to further clarify program policies and oversight procedures (Zieve, 2002).

These communication and education processes can reassure the public that the protection program is open and approachable and help to allay concerns that decisions are made “behind closed doors” for the benefit of investigators, institutions, or companies, rather than for the protection of participants.

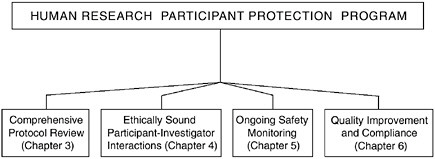

FUNCTIONS INTEGRAL TO THE PROTECTION SYSTEM

This chapter has focused on defining the purpose and structure of the HRPPP and the conditions necessary to ensure a viable system that will protect research participants. The remaining chapters will provide details about the four essential functions of a participant protection program— comprehensive protocol review; ethically sound participant-investigator interactions; ongoing safety monitoring; and quality improvement and compliance (see Figure 2.4). The following section will briefly outline each of these four functions, which may be carried out in a variety of ways within an organization’s protection program, and refer the reader to the appropriate chapter for further information.

Comprehensive Protocol Review

The initial review of a protocol is one of the most powerful tools for protecting research participants, because when used appropriately, it can prevent problems before the research begins. The role of the IRB is to provide participant protection through the careful ethical review of protocols, both at the outset and during the progress of a research project.

In order to provide a comprehensive ethical review, every proposal should receive a rigorous scientific review by an appropriately expert panel. It is important to stress that the process through which any protocol is reviewed should be commensurate with the potential risks participants will face. For example, the design of clinical trials should be based on sound statistical principles, and issues such as sample size, stopping rules, endpoints, and the feasibility of relating endpoints to objectives. These factors are pivotal to a successful trial and should be included in the technical or scientific review process.

In addition, every protocol should be explicitly reviewed for potential financial conflicts of interest at both the individual (investigator and research staff) and organizational levels.10 For those protocols in which po-

FIGURE 2.4 The Essential Functions of a Human Research Participant Protection Program

Four functions are fundamental to the protection of research participants and must be carried out by any assembled Human Research Participant Protection Program. These functions include comprehensive protocol review, ethically sound participant-investigator interactions, ongoing safety monitoring, and quality improvement and compliance.

tential conflict of interest is present, the initial in-depth determination regarding those conflicts and the development of any management strategies to deal with them should be conducted by a program element other than the IRB, which does not have the necessary resources or authority in this area. Therefore, this responsibility should lie with the research organization, and thus this aspect of the conflict of interest discussion is considered in Chapter 6.

In order to weave the three disparate aspects of proposal review together effectively (science, conflict of interest, ethics), the scientific and financial conflict of interest analyses for every project should be communicated in a clear and generally understandable format to the IRB for use in its comprehensive ethical deliberation and final assessment of the research protocol (see Chapter 3).

Ethically Sound Participant-Investigator Interactions

The interaction between the investigator and the participant is fundamental to the protection of research participants. Even the most elaborately and fully developed protection system will not work if the investigator does not adhere to ethical standards and obligations or if the research participant does not understand his or her responsibilities as a participant or give truly informed consent. In clinical trials, particularly those in which the investigator is also a treating physician, the need to assess participant un-

derstanding regarding the research nature of the study he or she is considering is especially important due to the pervasiveness of the therapeutic misconception (see Chapter 4). In addition, investigators should be aware of their own potential conflicts of interest and must disclose those with financial implications to the designated institutional body for assessment and any necessary management.

Informed consent is also fundamental to the ethical conduct of research. To fully respect participant autonomy, informed consent should be more than a signature on a form; it should be a process during which a structured conversation takes place to help the participant understand the study he or she may enter. In order to exercise their rights, participants should be prepared to ask questions about any aspect of the research that they would like to better understand and about their responsibilities as participants (see Chapter 4).

Ongoing Safety Monitoring

Ongoing oversight and monitoring of research is a critical program function. To be most effective, however, ongoing monitoring activities such as protocol review processes should be correlated to the level of risk posed to participants. In high-risk studies, regular, ongoing review is necessary to ensure that emerging data or evidence have not altered the risk-benefit assessment to the point that the risks are no longer reasonable. In addition, mechanisms are needed to monitor adverse events, unanticipated problems, and changes to a protocol and their subsequent incorporation into the informed consent process. Programs could better meet these responsibilities with improved federal guidance and funding and through some restructuring of the review and monitoring processes.

Research monitoring was foremost among the problems identified by Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG, 1998a, 2000a). Because IRBs are already overwhelmed with their primary responsibility to comprehensively review the ethics of research proposals, they may not be the entity best able to carry out the specialized monitoring of research studies. The committee believes that research monitoring—including adverse event reporting, DSMB/DMCs, ombudsman programs, reporting mechanisms for concerns or complaints, and consent monitoring programs—should be defined as part of program activities but should not rest solely with the IRB component (see Chapter 5).

Quality Improvement and Compliance

As detailed in Chapter 6, assessing institutional, IRB, and investigator compliance and implementing a CQI program can help to ensure that a

program is functioning adequately. The only mechanisms currently available for assessing such compliance include compliance assurances issued by DHHS and several other federal departments, site inspections of IRBs conducted by FDA, other types of site inspections for participant protection, and institutional audits. Some institutions have taken steps to establish ongoing mechanisms for assessing investigator and/or IRB compliance with regulations.11 However, institutions vary considerably in their efforts and abilities to monitor investigator compliance, from those that have no monitoring programs to those that conduct random audits. Assessing the performance of investigators and all program entities is an important part of protecting research participants and should be considered a serious responsibility of each protection program.

SUMMARY

A number of core systematic and complementary functions are essential to the protection of research participants and can be provided through a protection program that ensures that the research is conducted ethically. The entity within the protection program that carries out each function may vary according to the specifics of the protocol, but it is essential that some component within the established program have the clearly delineated responsibility for each core function in every study. To accomplish these essential functions, those at the highest levels of organizations that participate in human research should ensure that explicit lines of authority and responsibility are established and that a culture of ethics is pervasive throughout the organization. In addition, the research organization should ensure that those conducting and overseeing research with humans have the appropriate ethical and regulatory knowledge and that continuing education programs and consultative services are available to supplement basic education. Sponsors are obligated to effectively partner with research organizations to provide adequate resources for all elements of protection programs. Protection programs should be structured so that information regarding their general operations and specific protocol-related activities is accessible in a format useful to the public and, in particular, to current and potential research participants. In addition, research organizations and sponsors should ensure that all functions are carried out by responsible parties in order to fully protect research participants.