4

Implications of Past Chemical Events for Ongoing and Future Chemical Demilitarization Activities

Chapters 1 through 3 of this report are based on an examination of activities at Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) and Tooele Chemical Disposal Facility (TOCDF), both of which employ baseline incineration systems to destroy chemical agents. Third-generation incineration facilities are scheduled to begin operation in 2002 or 2003 at Anniston, Alabama, Umatilla, Oregon, and Pine Bluff, Arkansas. The committee believes that many of the observations and recommendations made in this report are applicable to all demilitarization facilities, including those that may not use incineration.

Evidence indicates that chemical demilitarization incineration facilities are safe as designed if they are operated properly and if the appropriate operating procedures and protocols are in place (NRC, 1996). The avoidance of risk during any type of process upset depends on having the necessary engineering controls in place and on the operator’s skill and training in using them to advantage. This level of preparedness requires in turn that a thorough hazard risk analysis be performed and that all personnel be thoroughly trained and given refresher courses at appropriate intervals. At both JACADS and TOCDF, extensive written procedures are in place for normal operations as well as for startup and shutdown, and operators receive systematic refresher training in these procedures. It can be expected that future chemical demilitarization facilities will also operate this way. Key factors for minimizing—if not eliminating—chemical events in the future include:

-

Sound risk and change management programs and procedures;

-

Effective safety programs that are focused on continuous improvement, and have the full visible support of all levels of management; and

-

Systems for efficient and timely program-wide dissemination of information and communication.

RISK AND MANAGEMENT OF CHANGE PROGRAMS ALREADY IN PLACE

This section describes the procedures that are in place for evaluation of change, including the risk associated with a change. The current Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program (CSDP) risk management program is fully described in Risk Assessment and Management at Deseret Chemical Depot and the Tooele Chemical Agent Disposal Facility (NRC, 1997). It is a multilevel program that defines policy, sets requirements, provides guidance on implementation, and, at the facility level, defines specific requirements the facility must meet and specific management processes that must be implemented. The CSDP risk management program is based on a long history of safety and hazard analysis and regulation by the Army. An informal risk management process was developed at the TOCDF in parallel with the site-specific quantitative risk analysis (QRA). This process was described in the NRC report Review of Systemization of the Tooele Chemical Agent Disposal Facility (NRC, 1996), which summarized a number of plant and operational changes that had been implemented as a result of accident scenarios identified in preliminary work on the QRA. As part of the risk management process, the following risk-monitoring activities have been introduced:

-

Performance evaluation (based on feedback from activities and incidents);

-

Emergency response exercises (periodic exercises on site, with Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Program (CSEPP) personnel);

-

Risk tracking (as new data become available, as risk models are improved, and when changes occur in the facility, the related changes in risk related to safety, environmental protection, and emergency preparedness will be calculated and tracked); and

-

As required by the Program Manager for Chemical Demilitarization (PMCD) now for essentially all facilities, participation in meetings and/or teleconferences about design lessons learned and programmatic lessons learned.

The Army’s formal risk management process is described in a program-wide document, Chemical Agent Disposal Facility Risk Management Program Requirements (U.S. Army, 1996c), which provides a basis for the CSDP risk management program. The risk management program is a framework for understanding and controlling all elements of risk within the disposal facility and the stockpile storage area. It links risk management needs to other specific requirements of the Army and other parties at top levels of management and identifies specific documents and references that apply to all CSDP facilities.

In January 1997, the Army issued its draft, A Guide to Risk Management Policy and Activities (the Guide) (U.S. Army, 1997b). This draft provides an overview of the processes for managing risks associated with Program Manager for Chemical Demilitarization (PMCD) activities and describes a process for managing changes that may affect the risk associated with PMCD activities. It defines issues that are matters of risk assessment and issues that are matters involving policy (value judgments) and attempts to establish an approach to integrating them and to involving the public in that integration.

The PMCD policy indicates that risk management is integrated into the normal functioning of the organization:

-

Operations are now based on the risk management program requirements document (U.S. Army, 1996c).

-

The Risk Management and Quality Assurance Office has been assigned the task of integrating risk management for operations, design, and construction.

-

The Environmental and Monitoring Office has been assigned the task of assessing hazards to the environment, the populace, and biota in terms of regulatory requirements.

-

The CSEPP has the task of planning for potential emergencies and providing liaisons with other emergency preparedness organizations. Note that this program is not a part of PMCD.

-

The Public Affairs Office is charged with providing liaisons among the public, the Citizens Advisory Commission (CAC), state authorities, and the Army to facilitate public involvement.

Another significant element in risk management is the management of change. Although changes are presumably made for good reasons, the overall safety of the facility could be compromised if the effects of change on risk estimates are not evaluated or understood. Changes need to be documented and analyzed to determine if they affect procedures, training, or other aspects of the program. This established configuration is based on the initial design of the facility and incorporates changes that have been approved and implemented. The established configuration is the basis for the plant’s up-to-date health risk assessment (HRA) and QRA.

If a proposed change is significant, assessing its value is acknowledged to be both a policy question and a factual question. Structured discussions focus attention on all factors that affect the decision, and information on the impact of the proposed change in significant cases should be made available to the public, to the CAC, and to state regulators, and public comments should be solicited when appropriate to the change contemplated. For the most significant changes (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Class 3) the Army, with the assistance of the controlling regulatory body, must schedule a public hearing. The definition of a RCRA Class 3 change is embodied in the existing federal regulations. The Army’s decision will take into account community desires (where appropriate to the complexity of the change) and needs as well as important facts and intangible factors, which are summarized in Table 4-1. Note that factor 6 in Table 4-1, “comparison to previous decisions,” ensures either that decisions are consistent or that the reasons for inconsistencies are clearly stated. A thorough consideration of uncertainties is also required. The Army is tasked to prepare

TABLE 4-1 Issues and Factors in Assessing the Value of Change Options

|

1 |

Public Input |

|

2 |

QRA Risk a. All available QRA risk measures, including expected fatalities, cancer incidence, fatalities at a one-in-a-billion probability, and probability of one or more fatalities b. Risk trade-offs: public versus worker, individual versus societal, processing versus storage c. Uncertainties in the technical assessment of risk d. Insights from sensitivity studies |

|

3 |

Hazard Evaluations |

|

4 |

HRA Risk a. Insight from sensitivity studies |

|

5 |

Programmatic a. Cost of the change relative to other proposals and program objectives b. Schedule for implementation c. Uncertainties in estimates d. Impact of implementation on overall objectives and schedule for disposal of the weapons and chemical agent e. Consideration of the improvement anticipated by this change with other proposed improvements |

|

6 |

Comparison to previous decisions |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted from U.S. Army (1997b), p. 53. |

|

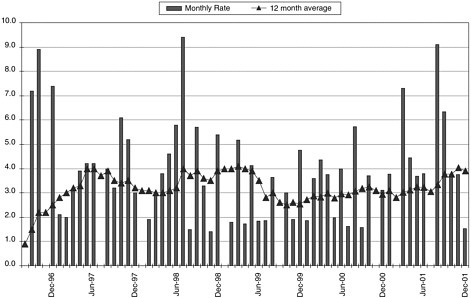

FIGURE 4-1 TOCDF recordable injury rate 12-month rolling average, August 1996 (the start of agent operations) through December 2001. SOURCE: Data up to 1998 from NRC (1999a); data for 1999 to 2001 from U.S. Army (2002b).

responses to all public comments and inform regulators and the CAC of decisions and their rationale.

If all issues are considered in an appropriate and timely manner, general consensus may be possible. But even if consensus is not reached, the Army, as decision maker, will provide a “synopsis of the considerations and a summary of the overall decision basis, listing the rationale for each factor” (U.S. Army, 1997b). In this way, interested parties can see if their concerns were considered and what effect they had on the decision.

SAFETY PROGRAMS

The safety of the public, the environment, and workers is a very significant part of a congressional mandate for the conduct of the chemical demilitarization program. The NRC’s Stockpile Committee previously expressed concern over production (agent destruction) having a higher priority than safety—at least from the standpoint of the contractors’ award fee criteria (NRC, 1999a and 2002). Responding to this observation, the Army revised the criteria to emphasize safety and production equally. An additional concern expressed repeatedly by the Stockpile Committee is a preoccupation with agent safety, to the detriment of traditional occupational health and safety programs and performance, and it has urged plant management to lead the operating sites toward a “safety culture” (NRC, 1999a).

At JACADS, significant progress was made in developing a safety culture, and during the latter phases of demilitarization operations the plant was consistently achieving excellent safety performance. This does not appear to have been the case at TOCDF (NRC, 1999a).

Although traditional performance indicators such as recordable injury rates (RIRs) at TOCDF are comparable to all-industry averages, there has been very little improvement in these metrics since operations began (Figure 4-1). Nor is there an indication that TOCDF has moved toward a safety culture at any appreciable rate, even though management has developed a TOCDF safety culture plan and has implemented several programs aimed at achieving the safety plan’s goals (NRC, 1999a). No additional findings or observations resulted from this study. The Committee on Evaluation of Chemical Events at Army Chemical Agent Disposal Facilities concurs with the Stockpile Committee in observing that the TOCDF is being operated in a safe manner, but that it can and should be continuously improving its safety programs and performance.

The Committee on Evaluation of Chemical Events also concurs with the Stockpile Committee in its belief that future

demilitarization facilities should be safer at start-up, as evidenced by performance metrics, than their predecessors. Such performance should not be difficult to achieve, given an effective programmatic lessons learned (PLL) program and the fact that several managers with chemical demilitarization experience will be working at the newer sites. Management and employees at new sites must begin the process of establishing a safety culture before operations commence.

PROGRAMMATIC LESSONS LEARNED PROGRAM

The PLL program—the principal means of communicating lessons learned both within and among the various chemical demilitarization facilities—is the PMCD’s only significant vehicle for communicating and coordinating risk, design, and operational issues among sites. The PLL program until recently was administered by PMCD with support from Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC). The program manager at SAIC was hired specifically because of his background in and extensive familiarity with detailed operating procedures, training, and quality control in a hazardous and demanding environment.

Dr. Mario Fiori, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations and Environment, presented his vision of some changes in the management and operating philosophy for the chemical demilitarization program to the Stockpile Committee on June 29, 2002. A major thrust of his presentation was that the contractors need to take “ownership” of the various aspects of the program for which they are responsible. Included in this change is the concept that PMCD would no longer be directly responsible for the PLL program, but that a contractor (yet to be selected from the two operating contractors) would instead be responsible for it.

The philosophy and purpose of the PLL program are:

-

to capture lessons learned during construction, equipment installation, systemization, operations, and closure, i.e., all phases of the operation

-

to provide assistance to the sites and PMCD in assessing and utilizing these lessons and experiences

-

to support PMCD’s emphasis on safety and environmental compliance

-

to reduce cost and schedule

-

to provide information to decision makers.

The PLL program is a comprehensive, multicomponent activity that is distributed across all PMCD demilitarization sites and includes workshops, assessments, technical bulletins, directed actions and updates, programmatic planning documents, site document comparisons, critical document reviews, and a “quick react” feature (Box 4-1).

PLL PROGRAM DATABASE

The PLL program is a mechanism for developing and maintaining information associated with lessons related to preconstruction and construction activities, systemization, operations, and closure of the chemical demilitarization facilities. The majority of lessons learned are captured in the PLL database, which contains considerable information and is potentially an excellent resource for helping to maintain a high level of operational safety and security. However, so much information is present that plant personnel believe it is hard to identify what will be helpful in any given situation.

The information in the PLL computerized database is available to all participants in the PLL program. The database is searchable using both Boolean logic (and key word(s)) and a decision tree. Although other means of communication exist for discussing the operational and safety issues arising at the demilitarization facilities (described below), essentially all the information is contained in the database. The data are continuously updated and include information from workshops since 1994 and document reviews before that date. Not all PLL program components that lead to data included in the database were in place in 1994, and some have been improved since their inception. For example, workshops, critical document reviews, quick reacts, and the PLL oversight board were initiated in 1994; the technical bulletin, in 1995; and operational assessments, in 1996.

The issues database was first provided to the chemical demilitarization sites in 1997, the programmatic planning documents became available in 1997, the site documents comparison began in 1998, the directed action philosophy was revised in 1999, the engineering change proposal (ECP) review process (which began in 1987) was integrated with PLL in 1999, and the lessons learned database (a different way of sorting and accessing the information) was started in 2000-2001. The PLL team has also developed a help line to facilitate easier use of the information.

Data in the PLL database are accessible to the following staff:

-

PMCD home office, which includes stockpile disposal, alternative technologies, non-stockpile materiel, cooperative threat reduction, support offices, and contractors.

-

Project Manager Chemical Stockpile Disposal (PMCSD) and Project Manager for Alternative Technologies and Approaches (PMATA) sites, which include field offices and site systems contractors.

-

Other stakeholders, including operations support command, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medi-

|

BOX 4-1 Additional PLL Program Components In addition to the computerized PLL database, the PLL program has several other significant components, including workshops, assessments, technical bulletins, directed actions and updates, programmatic planning documents, site document comparisons, critical document reviews, and a “quick react” feature. A brief description of these components follows.

The actual course of action is determined by PMCD operations management. |

-

cine, U.S. Army Materiel Systems Analysis Activity, Edgewood Chemical and Biological Center, and regulators.

As of August 2001 the database was organized as an “issues” database and included about 3200 items from which users can choose to determine lessons applicable to their particular problem. Currently the PLL team (SAIC) is developing a new way to present the data and estimates that 5000 lessons will ultimately be available from the issues represented to date.

Although not specifically categorized as such, a significant number of laboratory issues are included in the database. Until recently JACADS provided most of the cases, but TOCDF is now providing most of the issues. The database also includes lessons from Anniston, Pine Bluff, Aberdeen, Newport, and Umatilla, all of which are currently under construction or undergoing systemization. The PLL team categorized these lessons as design, 341; systemization, 687; operations, 843; and closure, 241. Of these, 196 are categorized as maintenance and 202 as training lessons. Prior to 1999, the ECPs were handled in a separate manner, but all ECPs have now been captured in the database. Permitting issues are also included in the database.

When the PLL program began in 1994-1995, the major source of issues was the review of documents (event reports, end-of-campaign reports, inspection reports, and so on.). Now most of the information comes from the facilitated workshops run by the PLL program, which allow input and peer review by multiple program personnel with expertise in the subjects under discussion. The initiators of the information (subjects) are primarily the chemical demilitarization sites, but some issues come from other program participants. As currently operating, the decision process used to determine the ultimate content of the PLL database is as follows:

-

PMCD approves the list of topics (subjects) used at a facilitated workshop.

-

Twice a year the PLL team holds workshops for environmental and environmental oversight topics.

-

The minutes from the workshop are prepared, reviewed, and tentatively approved by SAIC. These minutes are sent to PMCD for its review and approval.

-

PMCD then makes the final decision before the minutes and lessons learned are entered into the database.

-

The database is distributed as a CD-ROM to each chemical demilitarization site to be loaded onto its local area network. It is not available on the Internet or on a wide-area network.

There is no mechanism to track the use of the data, but SAIC stated to the committee that use of the data is extensive at the engineering change proposal (ECP) level, as well as at the chemical demilitarization sites during start-up and operation. The committee found no accurate means for assessing this assertion other than the use of anecdotal information. When queried, some operators were unaware of the database and its uses.

SAIC is in the process of prioritizing the data so that the highest-priority issues will require a response from the site. At present, a site does not have to respond, since there are too many issues in the database relative to staffing levels at the site. Additionally each ECP approved by any site is discussed at a biweekly ECP review teleconference. At a subsequent teleconference the sites inform the PLL team of what action will be taken regarding the ECP. These appear to be among the few issues that are handled in this more structured manner. The ECP review process consists of the following steps:

-

The sites approve the ECPs and forward approved ECPs to the PLL team.

-

The PLL team researches related issues and ECPs (using the database) and sends the ECPs and accompanying information to the other sites.

-

The ECP review team, which includes representatives of the PMCD office, demilitarization sites, Army Corps of Engineers, and the PLL team, conducts biweekly teleconferences and puts the decision documentation into the database.

The PLL database and PLL concept reflect a systematic effort to take advantage of lessons learned in one chemical demilitarization facility and use the information at another facility. At present only one facility is operating (TOCDF), and one is undergoing closure (JACADS). As more facilities come on line it will be more difficult to track the data and ensure that the most important issues are addressed at all sites. PMCD will need to strengthen the communication and implementing mechanisms in the near future. PMCD (SAIC) is currently developing a set of criteria for prioritizing the information in the PLL database. The intent is to create a few categories of issues (lessons), sorted according to relative importance. For instance, those with the highest priority (for example an important, operational safety directive) should probably be available and implemented at all facilities.

RESULTANT CHANGES

At JACADS and TOCDF, operations personnel did not appear to generalize lessons learned beyond the immediate equipment and task in the original incidents. There is room for making much wider use of these valuable lessons, such as by “mining” the information in the PLL database to detect patterns that may underlie several incidents. The effort to prioritize the data is a good start toward increasing the information’s usefulness. PMCD could also make better use of information available from industries such as the chemical and petroleum manufacturing sectors. Both have

very active trade associations and routinely share information regarding safety procedures and good operating and maintenance practices among different companies.

The destruction of chemical weapons was first begun at JACADS and its design was based on equipment and procedures developed at the Chemical Agent Munitions Disposal System (CAMDS) at Deseret Chemical Depot, Utah. Many design changes were made after operations had begun, some in response to chemical events, but most to correct recognized problems with the original design. (Both types are included in the PLL database.) For all operating chemical facilities, design changes are part of a continuing process aimed at taking advantage of lessons learned from ongoing operations, new technology as it is developed, or better procedures developed at a plant or transferred from another facility.

Many design changes have also been made to improve productivity (e.g., inclusion of the hot slag withdrawal system on the liquid incinerator (LIC) secondary burner, and the process, currently under review, for freezing the M2A1 projectiles at Anniston before disassembly to minimize spilling, and subsequent cleanup, of mustard agent). Design changes to improve operating safety, however, are not as readily identified except in direct response to a chemical event. For instance, the airflow systems handling ventilation throughout a plant as well as combustion air will have variable-speed motors driving the fans, allowing improved control of airflow, particularly at low rates (combustion airflow control was a problem for the operator during the May 8-9, 2000, incident at TOCDF).

A large number of changes have been made to operating procedures and equipment in response to the PLL program and based on incident reports from JACADS and TOCDF. Of the 24 recommendations for change resulting from the May 8, 2000, event at TOCDF, for example, all have been examined, although not all have required action at the newer plants because of differences in the feed mix and in the plant designs. In the committee’s view, some of the more significant changes made in response to the PLL are as follows:

-

Staggered automatic continuous air monitoring system (ACAMS) monitors are now being installed in exhaust ducts, to shorten the time for detection of any release of agent.

-

The deactivation furnace system (DFS) cyclone is contained in an enclosure that is monitored by an ACAMS.

-

There is a carbon filter on the incinerators’ exhaust.

-

As a result of the JACADS waste-bin event (discussed in detail in Chapters 2 and 3), drip trays have been added to rocket and mine lines, a search is on for combustible spill pillows, and spill pillows will generally be treated in the metal parts furnace, not the DFS.

-

The large isolation valves on the individual heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) carbon filter banks now have a small “bleed” valve, connecting to the exhaust flow, to maintain the filter bank at negative pressure even if it is temporarily out of service and to prevent migration of agent from the filter bank to the connecting vestibule. (Such migration of agent has been a problem in the past.)

Chapter 1 discusses the systems hazards analysis (SHA) performed for TOCDF. A primary purpose of a standard hazardous operation (HAZOP) analysis is to learn to anticipate where safety may be compromised. There have been many changes to the original design (see footnote 1, Chapter 5), some identified above and all included in the PLL database. It is not apparent that each of these design changes has been subjected to the appropriate level of HAZOP analysis. In view of the challenging nature of the chemical weapons disposal program and its perceived potential for harm, this aspect of the design process needs particular and ongoing attention.

It is common practice in industry for people who do the design and initial HAZOP analysis to be included on the plant start-up team. The people who did the actual detailed design work and participated in the HAZOP studies done as a part of the design process should also play a strong role in operator training in the use(s) of the HAZOP procedures and information. It is also common industry practice for companies to share nonproprietary information about safety issues, operating procedures, HAZOP findings, and so on. PMCD could make better use of the experiences of other industries, such as the chemical and petroleum refining industries, in the benchmarking of its procedures and processes.