2

The Need for a National Map

INTRODUCTION

This chapter reviews the need for and stakeholders in a national map, the policy context for the USGS role in building such a map, and related successful federal programs from which lessons could be learned. Without a well-defined need there will not be clear incentives for others to be partners with the USGS to build, maintain, and use The National Map. Building the partnerships that the USGS proposes is a complex and demanding task.

STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR NEEDS

From the USGS perspective The National Map (USGS, 2001) is needed to meet federal mapping requirements, to reduce unnecessary redundancy in federal mapping efforts, to continue to serve the needs of paper-map users, and to ensure standards for digital and paper maps. From the committee’s perspective there is a positive and significant benefit to the nation from coordinated, timely, and accurate topographic mapping. This benefit pertains to the myriad users at all levels, including that of the individual citizen. General facts about the surface of the Earth within the confines of the United States and its territories are public domain knowledge. These facts are of primary use to the assurance of

public safety during natural and human-induced disasters; can assure the effective use and protection of the nation’s resources; and support literally hundreds of applications that contribute to every citizen’s daily life. Accurate and timely map data aid the hunter, the boater, the letter carrier, the schoolchild, the city manager, the law enforcement officer, the scientist, and the President. In this way little has changed since 1807.

The value of The National Map approach for homeland security is apparent. Homeland security information must reside locally and be integratable nationally (e.g., see comments of Hugh Bender, Appendix D). When rapid response is needed in the critical first minutes and hours, local information is used by local first responders (e.g., see comments of Scott Oppmann and Ian von Essen, Appendix D), but when looking for patterns, trends, and tendencies, the national view will be critical. This was the case with the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, when local data in the form of New York City’s NYCMap (Keller and Kreizman, 2002) were prominent in helping in the rescue, recovery, and cleanup at the World Trade Center. As operations continued the federal role was to add new data and integrated information beyond the municipal boundaries of New York City.

All of these needs and applications must be balanced against the reality that The National Map will need to have a clear direction and focus and that it cannot be all things to all people and all applications (e.g., see comments of Yves Belzile, Appendix D), because this will generate unreasonable expectations and skepticism from data producers. In particular the committee distinguished between functions of unified coverage at a common scale, where the main contribution is to remove the arbitrary limitations of local districts through common specifications and extent versus the desire at all times to have the most accurate and up-to-date information, regardless of common standards or scale.

What do participants in the planning process for The National Map imagine it to be? During the workshop for this study, participants were asked to visualize and describe The National Map at some time in the future. The following vignette based on their input illustrates the range of stakeholders and process managers in The National Map.

It is now 2007 and the nation awaits preparation for the 2010 decennial census. Updating the TIGER (Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing) files for the 2000 census was a slow, massive, and costly undertaking, but there has now been a watershed change in thinking about how to coordinate the development of a consistent set of street centerlines for digital maps. New streets are routinely submitted in digital format by developers to municipal and county government offices to

ensure that they are given unique names and have logical street address numbering. These digital files are inserted into the county’s database. Once the county’s geodetic coordinator has verified the positional accuracy of the data and inserted a time stamp, this transaction is automatically sent to the state area integrator. At the state level the transaction is integrated with other transportation map themes. The state area integrator’s office automatically sends a notice to the state update subscribers who have requested notification of such transactions. The new roads are inserted into the E911 system. The transaction is then automatically forwarded to the USGS National Map coordinating office.

As guarantor of consistency and integration the National Map office runs a conflation routine and error-checking system to insert unique numbers for the street intersections and features according to the FGDC transportation feature standard. When these verification checks are completed, the new streets are inserted into the “online” version of the enhanced National Atlas, accessible immediately through Geospatial One-Stop, the Geography Network, and other distribution services, each of which determines whether it is time to update their distributed versions of the national road map layer. The National Atlas layers are backward integrated into the larger National Map that includes access to some proprietary data sources. The private sector can now redistribute the new roads data for vehicle navigation systems, location-based services, and specialized systems for the disabled community. Libraries and other on-demand map producers check The National Map to ensure that it is as current as possible. The entire data collection, verification, and distribution system is controlled by an approved workflow process and the system is virtual and transparent to the end user. The private sector has also developed a number of plug-ins for Web browsers that enable the users to develop their own user profiles, map design preferences, and specialized applications. There is a tab on the Google website for NSDI access.

Over the past five years several institutional changes have occurred. Geospatial One-Stop accelerated the completion of Framework data themes for the nation. Every thematic layer has accepted standards for content, attributes, spatial resolution, and accepted protocols for data capture. All federal agencies have agreed to use one consistent regional scheme to deal with states. The states have been able to acquire the updated address records from the utilities to ensure that the E911 system is complete, current, and accurate. Most states have developed their own system for aiding local governments, and 30 states have integrated street centerlines and addresses. There is a federal grant program to provide the “have not” state, local, county, and tribal governments with both human and technical capacity. NSGIC (National States Geographic Information Council)

representing all 53 states and territories is the recognized coordinating organization with the USGS and has become an effective body for raising congressional awareness about the importance of geographic data. Congress now provides a line item to maintain geographic data as part of the budget for the Department of Homeland Security. At the same time, a national fee for wireless communication has funded a high-resolution DEM (Digital Elevation Model) and the federal government is looking for new places to invest these funds. Federal agencies have minimal involvement in primary data capture. They serve as the quality assurance/quality control organizations.

The private sector has developed a robust market for location-based services and is providing a wide range of spatial data services to local governments, therefore companies are amenable to more liberal licensing agreements. Local governments recognize that the benefits of freely distributing their data outweigh the minimal revenue they earn. County planning offices generate substantial business opportunities due to frequent updating requirements. Graduation from high school requires attainment of geographic literacy standards. Several universities now offer courses in the NSDI. The libraries are infused with new funding for large-format paper-map reproduction, digital and hardcopy archiving, and organization of metadata. Researchers have provided the disabled with embedded assistive technology from NSDI to support personal navigation. Finally, to prepare for the 2010 census, the Bureau of the Census simply waits until January 2010 and downloads the current version of the enhanced National Atlas

Although perhaps optimistic (e.g., completed Framework layers, smooth workflow processes, availability of financial resources) the scenario articulates some of the changes that will be necessary if The National Map is to move from a concept to a reality.

CHANGING ROLES, FAMILIAR ISSUES

The activities of the USGS’s National Mapping program have changed significantly over the last 30 years, from a role of being a producer and maintainer of paper map products (principally the 1:24,000 seven-and-a-half-minute series) to that of developing digital core geographic databases through collaborative programs. Demand for federal digital map products has soared (Lemen, 1999). At the same time, the agency has suffered significant real budget reductions (e.g., USGS, 2002a), making it difficult for them to play the new role as catalyst for multipartner program collaboration. The cuts also caused the agency to scale back the updating

of the 1:24,000-scale map series. Increasingly the USGS has out-sourced such map tasks as orthophotography acquisition and maintenance.

The committee reviewed previous evaluations of federal mapping programs to build out the NSDI (see Appendix C). These programs have often been led by USGS. The committee was struck by the fact that in spite of over 20 years of largely convergent statements of clearly identified needs and strategies, a “national map” as envisioned in the preceding scenario has not been forthcoming. Numerous partially successful spatial data initiatives have come about that have in various degrees completed some of the parts of what should be considered a national map. This has happened largely in spite of, not because of, the various attempts at coordination at the federal level.

Fortunately the Office of Management and Budget Circular No. A-16 is unambiguous about the tasks federal agencies should perform (see Box 2.1) and the key role the FGDC should play in coordinating federal mapping. Given the critical earlier role of U.S. federal data in the spatial data community and in establishing world leadership in this nascent industry, the committee believes this federal role is also one of creating and maintaining a map of the nation for the public domain. The committee recognizes that the intermediate-scale (1:250,000 to 1:24,000), nationally consistent paper maps of the past are a poor future model. The opportunity to use existing local agency data creatively to provide higher resolutions, more detailed map scale, and timely map coverage should not be missed.

|

BOX 2.1 Since 1953 with revisions in 1967, 1990, and 2002, Circular No. A-16 has provided direction for federal agencies that produce, maintain, or use spatial data either directly or indirectly in the fulfillment of their mission. The circular establishes a coordinated approach to development of an electronic National Spatial Data Infrastructure and establishes the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) (see Box 1.3). Certain federal agencies have lead responsibilities for coordinating the national coverage and stewardship of specific spatial data themes. The roles of lead federal agencies include facilitating the development and implementation of needed FGDC standards and a plan for nationwide population of each data theme. The data themes led by the USGS are (in alphabetical order) as follows. |

|

Biological Resources. This dataset covers data pertaining to or descriptive of (nonhuman) biological resources and their distributions and habitats, including data at the suborganismal (genetics, physiology, anatomy), organismal (subspecies, species, systematics), and ecological (populations, communities, ecosystems, biomes) levels. Digital Orthoimagery. This dataset contains georeferenced images of the Earth’s surface, collected by a sensor in which image object displacement has been removed for sensor distortions and orientation, and terrain relief. Earth Cover. This theme uses a hierarchical classification system based on observable form and structure, as opposed to function or use. The theme differs from the vegetation and wetlands themes, which provide additional detail. Elevation (Terrestrial). These data are georeferenced digital representations of terrestrial surfaces, natural or engineered, which describe vertical position above or below a datum surface. Geographic Names. This dataset contains data or information on geographic place names deemed official for federal use by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. Geologic. The geologic spatial data theme pertains to all geologic mapping information and related geoscience spatial data (geophysical, geochemical, geochronologic, paleontologic) that can contribute to the National Geologic Map database. Hydrography. This data theme comprises such surface water features as lakes, ponds, streams and rivers, canals, oceans, and coastlines. Watershed Boundaries (co-leaders: Department of the Interior, USGS; and U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Conservation Service). This data theme encodes hydrologic, watershed boundaries into topographically defined sets of drainage areas. SOURCE: OMB (2002). |

BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES OF SHARING DATA

One goal set forth by the USGS (USGS, 2001) is to seek the most reliable, accurate, and timely data and use it to aggregate information up to a consistent national coverage. Prior national mapping efforts have created essentially stand-alone maps at specific scales, such as 1:100,000 and 1:24,000, whose update and production are independent operations. Although this was necessarily true in a paper map era, far more is

possible in the digital era. Best available data are often held by the private sector and are proprietary, or at the local, municipal, or county government level and are made available at significant cost or with restrictions on use. The problem becomes one of how these data can be “contributed” to a broader database, such as The National Map. The greatest challenges will be coordination among hundreds of participants and developing incentives for state and local governments to share and standardize their data or metadata (e.g., see comments of Scott Cameron, Appendix D). The greatest benefits will be an enrichment of the entire national coverage.

To achieve data sharing through the Mapping Partnership program (USGS, 2002b) the USGS has in the past used cooperative partnerships in the forms of conventional, innovative, and framework partnerships, and Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs). Partnerships have obvious benefits. For example, given a dual need for map revision and digital orthophotographic map production at the federal level, and the desire for a high-precision spatial database for facilities planning, local taxation, or even individual projects at the local level, the committee believes that the best way to conduct this mapping is by joint funding and shared commitments to acquisition support, map data processing, and data production. The committee believes that local strengths are in site-specific knowledge, transactional updates, programmatic requirements, and in utility; federal strengths are in coordination, support, development and application of standards, and data archiving and distribution. When the public domain is supported, local, state, and federal needs are met simultaneously and a powerful new model for public data sharing presents itself. Locally acquired data, including updates, could find their way into federally administered mapping programs and coarser-scale applications that suit national needs. In such an organizational circumstance all of the parties involved reap benefits.

BLANKETS AND QUILTS

The committee’s discussions covered two approaches to national mapping. On the one hand there is a need for a national map that is complete, consistent, at a common scale, and that can be updated selectively. A metaphor for this approach is a blanket, which covers a user uniformly at a single weight but is available universally at minimal cost. Earlier approaches that resulted in “blankets” are the 1:24,000 and 1:100,000 topographic map coverages, the Bureau of the Census’s TIGER files, and

the Digital Orthophoto Quadrangle (DOQ) map at 1:12,000 equivalent scale and 1-meter spatial resolution.1

An alternative approach follows the patchwork quilt metaphor. Here, individual squares are created by many processes (weaving, knitting, crochet), to different specifications, and for varied purposes, resulting in different materials and colors or fabric. In the metaphor the different weaves correspond to different map scales. Put another way, the different patches correspond to different levels of data resolution.

For individual pieces of the quilt to fit together there must be agreement on what size square to use, and on how the square patches will be assembled. For the creators willing to accept an overall set of design specifications, the benefit is in getting use of the quilt and in seeing their work in context. To further stretch the metaphor, the maintenance of each square could be the responsibility of its creator, thus creating a self-maintaining quilt.

The USGS vision for The National Map contains blanket and quilt components. The blanket component is the proposed continuation of the 1:24,000 series maps (USGS, 2001, p. 15), the proposed seamless national coverage with Landsat imagery (USGS, 2001, p. 10), and the proposed incorporation of the National Atlas into The National Map (USGS, 2001, p. 17). The quilt component is evident in the proposed high-resolution patches of data where local or state partners link their higher-resolution data (USGS, 2001, p. 2).

The importance of a quilt-first or bottom-up component to The National Map cannot be overstated. The blanket approach to national mapping has in the past been exclusively a top-down operation. As the USGS has built state and local cooperative arrangements as parts of cost sharing and cooperative research agreements, the blanket-only model has become increasingly strained. The most effective arrangements for federal collaboration are those in which both parties have a mutual interest in advancing the goals of accurate and timely mapping. The National Digital Orthophoto program (NDOP) and TIGER modernization programs are notable examples (see Boxes 2.2 and 2.3). Other examples

of partnerships that serve mutual interests are the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) National Watershed Boundary dataset project, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National GIS (Geographic Information System) Implementation plan, Bureau of Land Management’s Land Use plans, and the National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII).2 Additionally, lessons can be learned from the bottom-up organizational component of The National Map pilot projects3 (see Table 2.1).

Central to the success of the patchwork quilt model is that detailed mapping by a local agency or company can likely have value and quality added by being a part of The National Map. Federal mapping efforts also benefit from the continued reporting of modifications, updates, and new information that come from the local level. Models are available that favor exchanges based on incentives other than money, for example, exchanges based on the concept of equivalent value. Since updates are essentially the result of local processes, local reporting of updates-a sort of parallel processing for the nation-represents a way that a national map can be up-to-date, or at least sufficiently so to meet national needs, such as homeland security and natural disaster response. Acceptance of data into The National Map itself could have value. Similar to a “National Historical Landmark” designation, contributors would have their data certified as being from a “National Map partner.” Such designation could have implications for future data sharing, future cost sharing, and ongoing relationships associated with NSDI activities, and is more comprehensive and realistic than simply complying with fixed National Map Accuracy Standards. For example, a National Map partner county could be formally assured by the USGS that their census block and tract delineations conformed to locally maintained street and curbline map databases. When data are returned to participating cities and counties with increased value, the effect would also benefit the surrounding regions served by the city or county. When two adjacent counties conduct their mapping, neither has a mandate to ensure that a mapped road exiting one county arrives in the

correct place in the next county. If the USGS took responsibility for this kind of integration, both counties would benefit by participating in the project because each would get back a map showing their roads in the same position, thus connecting with each other. Ultimately, The National Map must be easy to understand, easy to participate in, and have obvious benefits for all stakeholders (e.g., see comments of Dennis Goreham, Appendix D).

|

BOX 2.2 Digital orthophotos are computer-compatible representations of aerial photographs with displacements and distortions caused by terrain relief, atmospheric conditions, and camera systems removed. The initial proposal for a National Digital Orthophoto program (NDOP) was made by the NRCS (formerly Soil Conservation Service) in May 1990. Primary support for the program came from the NRCS, the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS), and the USGS. The NDOP was funded cooperatively to provide national coverage in five years, with a 10-year average update cycle. Production for the estimated 220,000 digital Orthophoto quadrangles (DOQs) in the conterminous United States used the capability of the USGS and commercial contractors, the majority of work being done by the private sector. The federal land and resource management agencies are the principal users of DOQs, but many state and local governments and utilities with extensive geographic information system (GIS) operations are at the leading edge of innovation in digital Orthophoto applications. Applications include land and timber management, routing and habitat analysis, environmental impact assessment, evacuation planning, flood analysis, soil erosion assessment, facility management, and ground-water and watershed analysis. All DOQs are referenced to the North American Datum of 1983 (NAD 83). USGS DOQs must meet National Map Accuracy Standards for their respective scale map quadrangles. The specifications for the digital orthophotos are designed to accommodate DOQs from various producers. Published by the USGS as the Standard for Digital Orthophoto Quadrangles, they have been endorsed by the FGDC. Participation in the NDOP can occur through data-share, work-share, and joint-funding agreements. The results must meet the FGDC DOQ standards. The USGS Innovative Partnership program was developed to acquire digital spatial data that could be made available in the public domain from nonfederal sources. In October 1993 the list of Innovative |

|

Partnership data types was expanded to include DOQs. The program initially aimed at complete coverage in five years but was too ambitious given the federal budget situation. However, the rapid growth of state and local government interest and participation helped the program to near completion of first-time coverage of the nation in 2002. The NDOP partnerships have proven essential among all levels of the spatial data community, and serve as a good model for the nation in the development of other digital base map data. |

|

BOX 2.3 The entire nation was mapped to the block level for the first time for the 1990 decennial census. Although mapping by the Bureau of the Census was automated long before that, it was the TIGER line files of the 1990 census and the ability to disseminate these on CD-ROM that enabled this array of information to become widely available to the public for the first time. Now the bureau has signed a memorandum of understanding with the USGS to become a partner on street centerline data in The National Map (Robert Marx, Bureau of the Census, personal communication, 2002). Over the past two decades the Bureau of the Census has established a set of procedures and institutional arrangements for the creation, maintenance, and use of its TIGER line files. The representation of street centerlines and the associated address ranges are the key to a successful decennial census. The original version of the TIGER line files evolved during the 1980s through a cooperative agreement with the USGS. The addresses are compiled in the Master Address File (MAF), which is continually updated and becomes the Decennial Master Address File for the decennial census. The MAF is maintained collaboratively by the U.S. Postal Service, local governments, and the private sector. The Postal Service provides the bureau with its Delivery Sequence Files, which are tested for geocoding against the TIGER files to determine whether each address can be assigned to a unique census block. Through its 15 regional offices the bureau conducts a canvass of every block. Concurrently the MAF can be shared with local government units through the Local Update of Census Address (LUCA). The LUCA program provides the local government with an opportunity to identify addresses that should be added or deleted. These suggestions are field verified by the bureau. The bureau also has an arbitration process in place that includes independent review for any appeals that a local government may have to the |

|

MAF. As census day approaches the New Construction operation enables local government entities to identify new housing units. The private sector also plays an important role in the TIGER maintenance program. These arrangements vary from agreements with Geographic Data Technology to provide streets, street names, and address ranges to TIGER, with First Data Solutions to provide residential address lists, and with the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) to develop user-friendly software to manipulate features on maps. The creation of the American Community Survey (ACS) will provide an opportunity for continuous update of the MAP throughout the decade. The ACS program aims to provide “accurate up-to-date profiles of America’s communities every year” (Bureau of the Census, 2002a). When the ACS becomes operational in 2003 it will rely on a “self-enumeration through mail-out/mail-back methodology.” This method has procedures for telephone and field verification of the addresses of surveys not returned and will enable the bureau to update, maintain, and verify its address files on a continuing basis. The Federal Depository Library program (FDLP) of the U.S. Government Printing Office made the TIGER files and the census summary tape files for the 1990 census available to more than 1,300 libraries. Libraries are depositories for census information from the first census in 1790 forward; the electronic distribution of these data opened up new opportunities for libraries to provide access for analysis and interpretation over any desired geographic area. TIGER files and advances in technology have increased the speed with which GIS has become a multidisciplinary tool for interpreting and analyzing data of many types. By putting these data in the FDLP the Bureau of the Census demonstrated that public domain data can provide opportunities to the commercial sector for product development. At the same time the citizenry, including researchers, can benefit from government information in the public domain. A case in point is the participation of many of the FDLP libraries in the 1992 GIS Literacy project designed by the Association of Research Libraries working with ESRI. Workshops were conducted around the country for librarians to learn ArcView and identify software needs in the library community. Not only did hundreds of librarians become GIS literate but the commercial sector also learned how it could develop value-added products using the TIGER files and census data. The knowledge of GIS and its potential spread from libraries to K-12 programs in the nation’s schools. SOURCE: Bureau of the Census (2002a,b,c) |

The patchwork quilt approach for The National Map could meet the ambitious update goals set by the USGS. This type of national map would need to be flexible, be controlled autonomously rather than centrally, contain multiple spatial resolutions, be dividable spatially in almost any way (e.g., by census tracts, counties, congressional districts, watersheds, health districts), and would require a degree of public-private cooperation that is unprecedented (e.g., see comments of Hugh Bender, Appendix D). This patchwork quilt approach is bottom-up. If The National Map were built on this approach, the role of the USGS would be to act as an initiator of new working collaboratives, as a nurturer of collaboratives, as a coordinator, and as the guardian of consistency, standards, quality, and reliability. This role involves policing and facilitating content derived from the best available data contributed from local sources. It is separate from the provision of access tools enabling a user to view and utilize data. Many agencies, public, private and academic, will seek to provide portals to such a blanket and quilt system. Some systems are already based on this model, such as ESRI’s Geography Network and Geographic Data Technology’s Community Update.

TABLE 2.1 National Map Pilot Projects

|

Project/Location |

Focus Areas |

|

Delaware |

• Current, seamless base geographic datasets for entire state; • Partnerships with multiple agencies in Delaware; • Website addressing data integration issues: <http://www.datamil.udel.edu/nationalmappilot>. |

|

Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada Area |

• Integration of federal and local data; • Use of volunteer groups for updating datasets; • Collaboration with California on statewide vision for Framework data development and distribution. |

|

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina |

• Demonstration of current capabilities to provide access to, combine, view, and download a wide range of data themes from distributed data holdings at the national, state, and county levels; • Addressing such homeland security issues as continual service through mirror and backup data sites, and reprojecting data “on the fly.” |

TABLE 2.1 Continued

|

Project/Location |

Focus Areas |

|

Missouri |

• Multihazards risk assessment, mitigation, and emergency planning in southeastern Missouri; • Incorporation of best available data by working with local agencies; • Integration of geologic data with The National Map. |

|

Pennsylvania |

• Orthoimagery with frequent updates at county level to demonstrate data currency, archival, and maintenance functions of The National Map; • Hydrography data coordinated with local sources; • Land-cover data coordinated with state and local agencies. |

|

Texas |

• Expansion of USGS relationship with StratMap (Texas Natural Resources Information System database) as primary data source to The National Map; • Prototype map product and digital output mechanisms; • Refining local data linkage and integration techniques; • Website: <http://www.tnris.state.tx.us/digitalquad/>. |

|

Utah |

• Testing USGS capabilities to support critical transportation data for emergency response; • Urban and rural testbeds; • Integration of local transportation data. |

|

Washington-Idaho |

• Creation of new partnerships in rural areas lacking solid geospatial information; • Multijurisdictional, interstate project. |

|

U.S. Landsat |

• Providing access to Landsat satellite imagery as reference layer for The National Map; • Dynamic update cycle with archival and records retention; • Website: <http://gisdata.usgs.net/website/landsat>. |

|

SOURCE: USGS(2002d). |

|

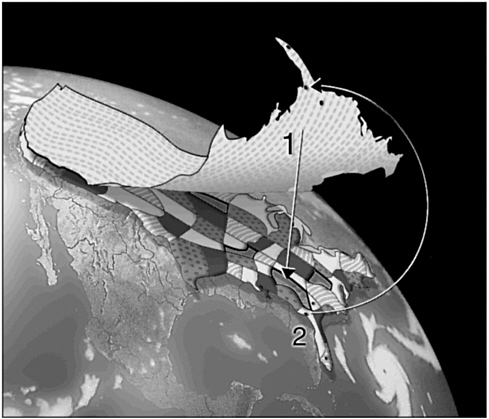

A combination approach of a blanket and quilt (see Figure 2.1) would ensure that a broad functional database was available nationally (the blanket), with

-

bottom-up feature-level4 updates;

-

enforced consistency;

-

a single scale (of, say, 1:12,000 or 1:24,000);

-

consistent generalization to alternative spatial reference frames (e.g., such spatial units or geographic extent as congressional or police districts); and

-

access over the Internet, with instantaneous availability for any citizen, agency, or community group.

At the same time, the patchwork quilt would contain public domain data and pointers to locally held proprietary data where such restrictions are necessary. Proprietary data could take the forms of (1) public domain metadata that includes contact and purchase or access information; (2) watermarked or encrypted data sets accessible for browsing but for download only by use of a controlled-access key; (3) degraded thumbnail images for browsing and limited use; or (4) fully public domain data. Any entity could contribute a data theme, but only those data used for updates in the blanket and that pass the acceptance tests of the USGS would receive The National Map status or endorsement.

Although this vision is somewhat consistent with that outlined by the USGS vision document (USGS, 2001), the facilitation and systems integration role for the USGS is a radical departure from prior activity. The success of integration efforts and later data update arrangements will depend on the ability to leverage local government, private, academic, and nonprofit support as a new kind of collaborative in a new kind of federal role. USGS is suited to take on this initiative because it has the experience, because it has a mandate in OMB Circular No. A-16, and because it already has part of the infrastructure (field offices and a spatially distributed system of centers) that is needed for success. The USGS support can come in several forms: as a broker of funding, a provider of technical expertise and advice, a provider of technical geospatial resources, and a coordinator of development efforts at all levels.

FIGURE 2.1 Illustration of the blanket and quilt metaphor and how the two components complement each other. The blanket covers holes in the quilt (1), and the quilt provides data and updates to the blanket (2). SOURCE: Susanna Baumgart, University of California, Santa Barbara.

SUMMARY

A national map as conceptualized by the USGS is justified and timely. Authority for such an enterprise is already delegated, yet the undertaking will require a cultural shift in the way that the USGS approaches its mapping. The future of mapping in the United States depends on forging partnerships among all levels of government and the private sector.