Executive Summary

Microbes live in every conceivable ecological niche on the planet and have inhabited the earth for many hundreds of millions of years. Indeed, microbes may be the most abundant life form by mass, and they are highly adaptable to external forces. The vast majority of microbes are essential to human, animal, and plant life. Occasionally, however, a microbe is identified as a pathogen because it causes an acute infectious disease or triggers a pathway to chronic diseases, including some cancers. Certainly, humankind remains ignorant of the full scope of diseases caused by microbial threats, as only a small portion of all microbes have been identified by currently available technologies.

Microbial threats continue to emerge, reemerge, and persist. Some microbes cause newly recognized diseases in humans; others are previously known pathogens that are infecting new or larger population groups or spreading into new geographic areas. Within the last 10 years, newly discovered infectious diseases have emerged in the United States (e.g., hantavirus pulmonary syndrome from Sin Nombre virus) and abroad (e.g., viral encephalitis from Nipah virus). During the same time, the worldwide resurgence of long-recognized infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, malaria, cholera, and dengue) has gained in force. The United States has seen the importation of infectious diseases, such as West Nile encephalitis, measles, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, malaria, and cyclosporiasis, from immigrants, U.S. residents returning from foreign destinations, and products of international commerce.

The realization of just how quickly newly discovered infectious diseases

can spread has generated a heightened appreciation of the inherent dangers of microbial pathogens. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) has become the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide in a mere 20 years since its discovery. Today, more than 40 million people are living with infection from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and 20 million people have died from AIDS. In just 3 years since West Nile virus was discovered in the Western Hemisphere, the virus has spread from its epicenter in New York to 39 states (including California), infecting thousands and killing hundreds.

The emergence and spread of microbial threats are driven by a complex set of factors, the convergence of which can lead to consequences of disease much greater than any single factor might suggest. Genetic and biological factors allow microbes to adapt and change, and can make humans more or less susceptible to infections. Changes in the physical environment can impact on the ecology of vectors and animal reservoirs, the transmissibility of microbes, and the activities of humans that expose them to certain threats. Human behavior, both individual and collective, is perhaps the most complex factor in the emergence of disease. Emergence is especially complicated by social, political, and economic factors—including the development of megacities, the disruption of global ecosystems, the expansion of international travel and commerce, and poverty—which ensure that infectious diseases will continue to plague us. Today we also face the threats of intentionally introduced biological agents. The risks to humankind from the willful spread of highly virulent and contagious microbes are considerable, and we in the United States are preparing to defend ourselves with new vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics against the many microbes that might be used in a biological attack. We also are cognizant of the need to rebuild public health infrastructure locally and globally as an indispensable means of reacting to such threats.

Can a focus on naturally occurring microbial threats be maintained in the face of expanded efforts to contain the threat of intentional biological attacks? Some may ask which is the greater risk—the intentional use of a microbial agent to cause sudden, massive, and devastating epidemics of disease, or the continued emergence and spread of natural diseases such as tuberculosis, AIDS, malaria, influenza, and multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. It is a tragic reality that hundreds of people die from naturally occurring infections every hour, whereas until now, intentional biological attacks on a major scale have remained a theoretical risk, rife with political as well as technical uncertainties. HIV/AIDS has taught us the importance of remaining vigilant to the devastation of naturally arising epidemics, which can have profound effects not only on individuals, but also on whole nations and regions. The economic and social disruption that often follows

an infectious disease outbreak and typically accompanies the persistent burden due to endemic infectious diseases can be a major destabilizing force for any nation. The challenge is to keep our concerns and responses in reasonable balance. This report contains prescriptions for acting wisely to integrate our surveillance, control, and prevention efforts aimed at natural scourges with enhanced security from intentional biological attacks.

Throughout history, humans have struggled to control both the causes and the consequences of infectious diseases, and we will continue to do so into the foreseeable future. Disease control for many pathogens includes vaccines and pharmaceuticals, but how long these controls will remain effective or even available is uncertain. We appear less able (or willing) to develop new antimicrobials and vaccines than once was the case, especially for infectious diseases that affect developing countries disproportionately. A variety of technical, political, social, and economic issues challenge our ability to develop and deploy new antimicrobials and vaccines. The burden of infectious diseases has become further compounded as resistance to vector-control agents and antimicrobials has grown pervasive not only in the United States, but also worldwide.

The 1992 Institute of Medicine report Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States took a fresh look at the impact of new and reemerging infectious diseases on the United States. In 2001, the Committee on Emerging Microbial Threats to Health in the 21st Century was charged to identify, review, and assess the current state of knowledge regarding factors in the emergence of infectious diseases; to assess the capacity of the United States to respond to emerging microbial threats to health; and to identify potential challenges and opportunities for domestic and international public health actions to strengthen the detection and prevention of, and response to, microbial threats to human health. The committee acknowledges that infectious diseases in animals and agriculture have indirect effects on human health (e.g., reductions in available food sources, economic and psychological hardships for food-animal producers due to culling), and are an important component of the overall assessment of infectious disease response and control. The scope of this report, however, was limited to infectious diseases in humans.

SPECTRUM OF MICROBIAL THREATS

The spectrum of microbial threats is a continuum that comprises the emergence of newly recognized infectious diseases, the resurgence of endemic diseases, the appearance of new antimicrobial-resistant forms of diseases, the recognition of the infectious etiology of chronic diseases, and the intentional use of biological agents for harm.

FACTORS IN EMERGENCE

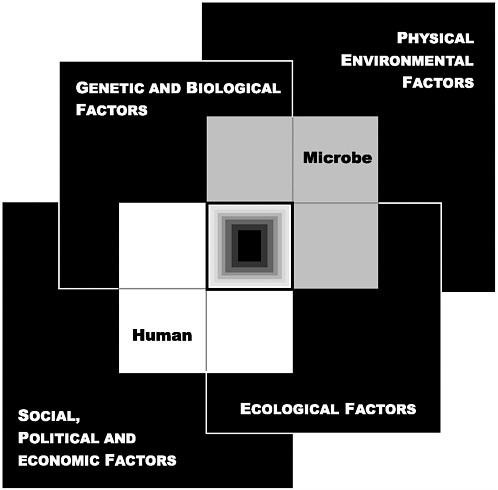

The convergence of any number of factors can create an environment in which infectious diseases can emerge and become rooted in society. A model was developed to illustrate how the convergence of factors in four domains impacts on the human–microbe interaction and results in infectious disease (see Figure ES-1). Ultimately, the emergence of a microbial threat derives from the convergence of (1) genetic and biological factors; (2) physical environmental factors; (3) ecological factors; and (4) social, political, and economic factors. As individual factors are examined, each can be envisioned as belonging to one or more of these four domains. The following individual factors in emergence are examined in this report:

Microbial adaptation and change. Microbes are continually undergoing adaptive evolution under selective pressures for perpetuation. Through structural and functional genetic changes, they can bypass the human immune system and infect human cells. The tremendous evolutionary potential of microbes makes them adept at developing resistance to even the most potent drug therapies and complicates attempts at creating effective vaccines.

Human susceptibility to infection. The human body has evolved with an abundance of physical, cellular, and molecular barriers that protect it from microbial infection. Susceptibility to infection can result when normal defense mechanisms are altered or when host immunity is otherwise impaired by such factors as genetically inherited traits and malnutrition.

Climate and weather. Many infectious diseases either are strongly influenced by short-term weather conditions or display a seasonality indicating the possible influence of longer-term climatic changes. Climate can directly impact disease transmission through its effects on the replication and movement (perhaps evolution) of pathogens and vectors; climate can also operate indirectly through its impacts on ecology and/or human behavior.

Changing ecosystems. In general, changes in the environment tend to have the greatest influence on the transmission of microbial agents that are waterborne, airborne, foodborne, or vector-borne, or that have an animal reservoir. Given today’s rapid pace of ecological change, understanding how environmental factors are affecting the emergence of infectious diseases has assumed an added urgency.

Economic development and land use. Economic development activities can have intended or unintended impacts on the environment, resulting in eco-

FIGURE ES-1 The Convergence Model. At the center of the model is a box representing the convergence of factors leading to the emergence of an infectious disease. The interior of the box is a gradient flowing from white to black; the white outer edges represent what is known about the factors in emergence, and the black center represents the unknown (similar to the theoretical construct of the “black box” with its unknown constituents and means of operation). Interlocking with the center box are the two focal players in a microbial threat to health—the human and the microbe. The microbe–host interaction is influenced by the interlocking domains of the determinants of the emergence of infection: genetic and biological factors; physical environmental factors; ecological factors; and social, political, and economic factors.

logical changes that can alter the replication and transmission patterns of pathogens. A growing number of emerging infectious diseases arise from increased human contact with animal reservoirs as a result of changing land use patterns.

Human demographics and behavior. An infectious disease can result from a behavior that increases an individual’s risk of exposure to a pathogen, or from the increased probability of exchange of a communicable infectious disease between humans as the world’s population increases in absolute number. Additional factors include demographic changes such as urbanization and the growth of megacities; the aging of the world’s population and the associated increased risk of infection; and the growing number of individuals immunocompromised by cancer chemotherapy, chronic diseases, or infection with HIV.

Technology and industry. Infectious diseases have emerged as a direct result of changes in technology and industry. Advances in medical technologies, such as blood transfusions, human organ and tissue transplants, and xenotransplantation (using an animal source), have created new pathways for the spread of certain infections. Even the manner in which animals are raised as food products, such as the use of antimicrobials for growth production, has abetted the rise in infectious diseases by contributing to antimicrobial resistance.

International travel and commerce. The rapid transport of humans, animals, foods, and other goods through international travel and commerce can lead to the broad dissemination of pathogens and their vectors throughout the world. Microbes that can colonize without causing symptoms (e.g., Neisseria meningitidis) or can infect and be transmissible at a time when infection is asymptomatic (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C) can spread easily in the absence of recognition in traveling or migrant hosts. Pathogens in meat and poultry, such as the agents of “mad cow disease,” can also be delivered unintentionally across borders, while the vectors of tropical diseases can be transported in cargo holds or in the wheel wells of international aircraft.

Breakdown of public health measures. A breakdown or absence of public health measures—especially a lack of potable water, unsanitary conditions, and poor hygiene—has had a dramatic effect on the emergence and persistence of infectious diseases throughout the world. The breakdown of public health measures in the United States has resulted in an increase in nosocomial infections, difficulties in maintaining adequate supplies of vaccines in recent years, immunization rates that are far below national targets for many population groups (e.g., influenza and pneumococcal immunizations in adults), and a paucity of needed expertise in vector control for diseases such as West Nile encephalitis.

Poverty and social inequality. At the same time that infectious diseases have

significant and far-reaching economic implications, social inequality, driven in large part by poverty, is a major factor in emergence. Mortality from infectious diseases is closely correlated with transnational inequalities in income. Global economic trends affect not only the personal circumstances of those at risk for infection, but also the structure and availability of public health institutions necessary to reduce risks.

War and famine. War and famine are closely linked to each other and to the spread of infectious diseases. Displacement due to war and the fairly consistent sequelae of malnutrition due to famine can contribute significantly to the emergence and spread of infectious diseases such as malaria, cholera, and tuberculosis.

Lack of political will. If progress is to be made toward the control of infectious diseases, the political will to do so must encompass not only governments in the regions of highest disease prevalence, but also corporations, officials, health professionals, and citizens of affluent regions who ultimately share the same global microbial landscape. The complacency toward the threat of infectious diseases that has become somewhat entrenched in developed countries must reverse in direction if we are to avoid losing windows of opportunity to reduce the global burden of infection.

Intent to harm. The world today is vulnerable to the threat of intentional biological attacks, and the likelihood of such an event is high. The U.S. public health system and health care providers should be prepared to address various biological agents that pose a risk to national security because of their potential to cause large numbers of deaths and widespread social disruption.

Recognizing and addressing the ways in which the factors in emergence converge to change vulnerability to infectious diseases is essential to the development and implementation of effective prevention and control strategies. Detecting and responding to global infectious disease threats is in the economic, humanitarian, and national security interests of the United States and essential to the health of its people.

ADDRESSING THE THREATS: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The response to a microbial threat—from detection to prevention and control—is a multidisciplinary effort involving all sectors of the public health, clinical medicine, and veterinary medicine communities. The committee’s recommendations emerged from focused deliberations and applica-

tion of the criteria of urgency, priority, and amenability to immediate action. Given that infectious diseases are a significant threat to the health of the world’s population, several of the committee’s recommendations could be justified solely on the basis of humanitarian need; all are justified as being in the best interest of the United States to protect the health of its own citizens.

Enhancing Global Response Capacity

Infectious diseases are a global threat and therefore require a global response. Nations not only must be concerned about the endemic diseases that plague their own citizens, but also must expand their concerns to include the global burden of disease that ultimately encompasses the gamut of potential threats—even if these threats are not currently found within their borders. While the true burden of infectious diseases in many areas of the world is unknown, the greatest burden occurs within developing countries, where an estimated one in every two persons dies from such a disease. The United States’ capacity to respond to microbial threats must therefore include a significant investment in the capacity of developing countries to monitor and address microbial threats as they arise.

The United States should seek to enhance the global capacity for response to infectious disease threats, focusing in particular on threats in the developing world. Efforts to improve the global capacity to address microbial threats should be coordinated with key international agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and based in the appropriate U.S. federal agencies (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the Department of Defense [DOD], the National Institutes of Health [NIH], the Agency for International Development [USAID], the Department of Agriculture [USDA]), with active communication and coordination among these agencies and in collaboration with private organizations and foundations. Investments should take the form of financial and technical assistance, operational research, enhanced surveillance, and efforts to share both knowledge and best public health practices across national boundaries.

Improving Global Infectious Disease Surveillance

Global surveillance, especially for newly recognized infectious diseases, is crucial to responding to and containing microbial threats before isolated outbreaks develop into regional or worldwide pandemics.

The United States should take a leadership role in promoting the implementation of a comprehensive system of surveillance for global infec-

tious diseases that builds on the current global capacity of infectious disease monitoring. This effort, of necessity, will be multinational and will require regional and global coordination, advice, and resources from participating nations. A comprehensive system is needed to accurately assess the burden of infectious diseases in developing countries, detect the emergence of new microbial threats, and direct prevention and control efforts. To this end, CDC should enhance its regional infectious disease surveillance; DOD should expand and increase in number its Global Emerging Infections Surveillance (GEIS) overseas program sites; and NIH should increase its global surveillance research. In addition, CDC, DOD, and NIH should increase efforts to develop and arrange for the distribution of laboratory diagnostic reagents needed for global surveillance, transferring technology to other nations where feasible to ensure self-sufficiency and sustainable surveillance capacity. The overseas disease surveillance activities of the relevant U.S. agencies (e.g., CDC, DOD, NIH, USAID, USDA) should be coordinated by a single federal agency, such as CDC. Sustainable progress and ultimate success in these efforts will require health agencies to broaden partnerships to include nonhealth agencies and institutions, such as the World Bank.

Rebuilding Domestic Public Health Capacity

Strong and well-functioning local, state, and federal public health agencies working together represent the backbone of an effective response to infectious diseases. The U.S. capacity to respond to microbial threats is contingent upon a public health infrastructure that has suffered years of neglect. Upgrading current public health capacities will require considerably increased, sustained investments.

U.S. federal, state, and local governments should direct the appropriate resources to rebuild and sustain the public health capacity necessary to respond to microbial threats to health, both naturally occurring and intentional. The public health capacity in the United States must be sufficient to respond quickly to emerging microbial threats and monitor infectious disease trends. Prevention and control measures in response to microbial threats must be expanded at the local, state, and national levels and be executed by an adequately trained and competent workforce. Examples of such measures include surveillance (medical, veterinary, and entomological); laboratory facilities and capacity; epidemiological, statistical, and communication skills; and systems to ensure the rapid utility and sharing of information.

Improving Domestic Surveillance Through Better Disease Reporting

Open lines of communication and good working relationships among health care providers, clinical laboratories, and public health authorities are essential to robust systems of surveillance and effective implementation of disease investigation and response activities. The reporting of infectious diseases by health care providers and laboratories, however, remains inadequate.

CDC should take the necessary actions to enhance infectious disease reporting by medical health care and veterinary health care providers. Innovative strategies to improve communication between health care providers and public health authorities should be developed by working with other public health agencies (e.g., the Food and Drug Administration [FDA], the Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], USDA, the Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], state and local health departments), health sciences educational programs, and professional medical organizations (e.g., the American Medical Association, the American Society for Microbiology, the American Nurses Association, the American Veterinary Medical Association, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, the Association of Teachers of Preventive Medicine).

CDC should expeditiously implement automated electronic laboratory reporting of notifiable infectious diseases from all relevant major clinical laboratories (e.g., microbiology, pathology) to their respective state health departments as part of a national electronic infectious disease reporting system. The inclusion of antimicrobial resistance patterns of pathogens in the application of automated electronic laboratory reporting would assist in the surveillance and control of antimicrobial resistance.

Exploring Innovative Systems of Surveillance

The ability to gather and analyze information quickly and accurately would improve the nation’s ability to recognize natural disease outbreaks, track emerging infections, identify intentional biological attacks, and monitor disease trends. Surveillance systems within the United States, however, remain fragmented and have not evolved at the same rate as the electronic technological advances that could significantly improve the timeliness and integration of data collection.

Research on innovative systems of surveillance that capitalize on advances in information technology should be supported. Before widespread implementation, these systems should be carefully evaluated for their usefulness in detection of infectious disease epidemics, including their potential for detection of the major biothreat agents, their ability to monitor the spread of epidemics, and their cost-effectiveness. Research on syndromic surveillance systems should continue to assess such factors as the capacity to transmit existing data electronically, to standardize chief complaint or other coded data, and to explore the usefulness of geospatial coding; CDC should provide leadership in such evaluations. In addition, promising approaches will need to be coordinated nationally so that data can be shared and analyzed across jurisdictions.

Developing and Using Diagnostics

Etiologic diagnosis—identifying a microbial cause of an infectious disease—is the cornerstone of effective disease control and prevention efforts, including surveillance. Etiologic diagnosis has declined significantly over the past decade. A dangerous consequence of decreased etiologic diagnosis has been an increase in the inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Improving etiologic diagnosis would be of value to human health worldwide in directing appropriate therapy, as well as informing disease surveillance and response activities.

CDC and NIH should work with FDA, other government agencies (e.g., DOD, USDA, the national laboratories), and industry on the development, assessment, and validation of rapid, inexpensive and cost-effective, sensitive, and specific etiologic diagnostic tests for microbial threats of public health importance.

Public health agencies and professional organizations (e.g., those concerned with patient care, health education, and microbiological issues) should promulgate and publicize guidelines that call for the intensive application of existing diagnostic modalities and new modalities as they are established. Such guidelines should be incorporated into continuing education programs, board examinations, and accreditation practices. Payers for health care should cover diagnostic tests for infectious diseases to increase specific diagnoses and thereby inform both public health and medical care, including monitoring of inappropriate use of antimicrobials.

Educating and Training the Microbial Threat Workforce

The workforce necessary to accomplish the needed improvement in the national capacity to respond to microbial threats must be supported with strong training programs in the applied epidemiology of infectious disease prevention and control. As a vital component of this workforce, the knowledge and skills needed to confront microbial threats must be better integrated into the training of all health care professionals to ensure a prompt and effective response to any and all infectious disease threats, whether naturally occurring or maliciously introduced.

CDC, DOD, and NIH should develop new and expand upon current intramural and extramural programs that train health professionals in applied epidemiology and field-based research and training in the United States and abroad. Research and training should combine field and laboratory approaches to infectious disease prevention and control. Federal agencies should develop these programs in close collaboration with academic centers or other potential training sites. Domestic training programs should include an educational, hands-on experience at state and local public health departments to expose future and current health professionals to new career options, such as public health.

Vaccine Development and Production

Our nation—and the world—faces a serious crisis with respect to vaccine development, production, and deployment. Concern has increased over the inadequacy of vaccine research and development efforts, periodic shortages of existing vaccines, and the lack of vaccines to prevent diseases that affect persons in developing countries disproportionately. Yet, too little has been done to resolve these issues. The evolving threat of intentional biological attacks makes the need for focused attention and action even more critical.

The challenges associated with vaccine innovation, production, and deployment are many and complex. Solutions will require a novel, coordinated approach among government agencies, academia, and industry. Issues that must be examined and addressed in a more meaningful and systematic fashion include the identification of priorities for research, the determination of effective incentive strategies for developers and manufacturers, liability concerns, and streamlining of the regulatory process. Currently, the federal government is neither addressing all of these challenges at a sufficiently high level nor providing adequate resources. Leadership, empowerment, and accountability are urgently needed at the cabinet level to

ensure a comprehensive, integrated vaccine strategy that will address the following critical elements:

The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure the formulation and implementation of a national vaccine strategy for protecting the U.S. population from endemic and emerging microbial threats. Only by focusing leadership, authority, and accountability at the cabinet level can the federal government meet its national responsibility for ensuring an innovative and adequately funded research base for existing and emerging infectious diseases and the development of an ample supply of routinely recommended vaccines. The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services should work closely with other relevant federal agencies (e.g., DOD, the Department of Homeland Security, VA), Congress, industry, academia, and the public health community to carry out this responsibility.

The U.S. Secretary of Defense, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security should work closely with industry and academia to ensure the rapid development and deployment of vaccines for naturally occurring or intentionally introduced microbial threats to national security. The federal government should explore innovative mechanisms, such as cooperative agreements between government and industry or consortia of government, industry, and academia, to accelerate these efforts.

The Administrator of USAID, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Secretary of State should work in cooperation with public and private partners (e.g., leaders of foundations and other donor agencies, industry, WHO, UNICEF, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) to ensure the development and distribution of vaccines for diseases that affect populations in developing countries disproportionately.

Need for New Antimicrobial Drugs

Drug options for treatment of infections are becoming increasingly limited, largely as a result of growing antimicrobial resistance. Many generic but essential antibiotics are in short supply, and the development of new antibiotics has been severely curtailed. In the past three decades, only two new classes of antibiotics have been developed, and resistance to one class emerged even before the drugs entered the commercial market. Only four large pharmaceutical companies with antibiotic research programs

remained in existence in 2002 and not one new class of antibiotics is in advanced development. Likewise, antivirals for only a limited number of viral diseases are available, and few are in development. In the event of a natural or intentionally introduced microbial threat, antimicrobials may be the only available first line of response. A readily available supply, therefore, should be a priority of preparedness plans.

The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure the formulation and implementation of a national strategy for developing new antimicrobials, as well as producing an adequate supply of approved antimicrobials. The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services should work closely with other relevant federal agencies (e.g., DOD, the Department of Homeland Security), Congress, industry, academia, and the public health community to carry out this responsibility.

The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security should protect our national security by ensuring the stockpiling and distribution of antibiotics, antivirals (e.g., for influenza), and antitoxins for naturally occurring or intentionally introduced microbial threats. The federal government should explore innovative mechanisms, such as cooperative agreements between government and industry or consortia of government, industry, and academia, to accelerate these efforts.

Inappropriate Use of Antimicrobials

The world is facing an imminent crisis in the control of infectious diseases as the result of a gradual but steady increase in the resistance of a number of microbial agents to available therapeutic drugs. The problem is of global concern and is creating dilemmas for the treatment of infections in both hospitals and community health care settings. Moreover, as noted above, the pharmaceutical industry is developing fewer new antimicrobials than in previous years. Therefore, immediate action must be taken to preserve the effectiveness of available drugs by reducing the inappropriate use of antimicrobials in human and animal medicine.

CDC, FDA, professional health organizations, academia, health care delivery systems, and industry should expand efforts to decrease the inappropriate use of antimicrobials in human medicine through (1) expanded outreach and better education of health care providers, drug dispensers, and the general public on the inherent dangers associated with the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, and (2) the increased use

of diagnostic tests, as well as the development and use of rapid diagnostic tests, to determine the etiology of infection and thereby ensure the more appropriate use of antimicrobials.

FDA should ban the use of antimicrobials for growth promotion in animals if those classes of antimicrobials are also used in humans.

Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Disease Control

Vector-borne and zoonotic diseases remain major causes of morbidity and mortality in humans living in tropical climates, and represent a large portion of newly emerged diseases worldwide. Vector-borne and zoonotic pathogens have the ability to spread rapidly across broad geographical areas, as evidenced by the spread of West Nile virus across the United States. Exacerbating the situation is the potential for many vector-borne and zoonotic agents to be weaponized and used by terrorists. The national and international capacity to address these diseases must be strengthened by rebuilding the workforce and infrastructure, and developing the tools necessary to respond appropriately to such threats.

CDC, DOD, NIH, and USDA should work with academia, private organizations, and foundations to support efforts at rebuilding the human resource capacity at both academic centers and public health agencies in the relevant sciences—such as medical entomology, vector and reservoir biology, vector and reservoir ecology, and zoonoses— necessary to control vector-borne and zoonotic diseases.

DOD and NIH should develop new and expand upon current research efforts to enhance the armamentarium for vector control. The development of safe and effective pesticides and repellents, as well as novel strategies for prolonging the use of existing pesticides by mitigating the evolution of resistance, is paramount in the absence of vaccines to prevent most vector-borne diseases. In addition, newer methods of vector control—such as biopesticides and biocontrol agents to augment chemical pesticides, and novel strategies for interrupting vector-borne pathogen transmission to humans—should be developed and evaluated for effectiveness.

CDC, DOD, and NIH should work with state and local public health agencies and academia to expand efforts to exploit geographic information systems (GIS) and robust models for predicting and preventing the emergence of vector-borne and zoonotic diseases.

Comprehensive Infectious Disease Research Agenda

To ensure that the United States is strategically poised to protect itself against the threat of infectious diseases and to maximize its assistance in global efforts to combat these diseases, further investments must be made to support a diverse array of multidisciplinary research domains. These new investments must be part of an overall strategy for improved public health preparedness and protection against infectious disease threats. A comprehensive system of accountability must be in place to ensure that no critical areas are neglected. Given that the emergence of infectious diseases is the result of a complex convergence of factors, it is clear that multidisciplinary studies are greatly needed.

NIH should develop a comprehensive research agenda for infectious disease prevention and control in collaboration with other federal research institutions and laboratories (e.g., CDC, DOD, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation), academia, and industry. This agenda should be designed to investigate the role of genetic, biological, social, economic, political, ecological, and physical environmental factors in the emergence of infectious diseases in the United States and worldwide. This agenda should also include the development and assessment of public health measures to address microbial threats. A sustained commitment to a robust research agenda must be a high priority if the United States is to dramatically reduce the threat of naturally occurring infectious diseases and intentional uses of biological agents. The research agenda should be flexible to permit rapid assessment of new and emerging threats, and should be rigorously reevaluated on a 5-year basis to ensure that it is addressing areas of highest priority.

Interdisciplinary Infectious Disease Centers

As noted, addressing the highly complex nature of infectious disease emergence requires the involvement of experts from a broad range of disciplines and health sectors. The present structure of academic and public health institutions, however, requires that most of these arenas operate independently of each other. Opportunities for collaboration and synergism will be enhanced if experts convene under the same roof (or on the same campus) to discuss a problem, thus avoiding lost opportunities for collaboration and reducing often unnecessary redundancies of effort and expense. Furthermore, an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach can facilitate the training of the workforce needed to address the problems of emerging microbial threats facing the world today.

Interdisciplinary infectious disease centers should be developed to promote a multidisciplinary approach to addressing microbial threats to health. These centers should be based within academic institutions and link (both physically and virtually) the relevant disciplines necessary to support such an approach. They would collaborate with the larger network of public agencies addressing emerging infectious diseases (e.g., local and state health agencies, CDC, DOD, the U.S. Department of Energy, FDA, the Food Safety and Inspection Service, NIH, the National Science Foundation, USAID, USDA), interested foundations, private organizations, and industry. The training, education, and research that these centers would provide are a much-needed resource not only for the United States, but also for the entire world.

CONCLUSION

Today’s world is truly a global village, characterized by growing concentrations of people in huge cities, increasing global commerce and travel, progressive damage to natural ecosystems, poverty, famine, and social disruption. One can safely predict that infectious diseases will continue to emerge, and that we will encounter unpleasant surprises, as well as increases in already worrisome trends. Depending on present policies and actions, this situation could lead to a catastrophic storm of microbial threats.

Thus while dramatic advances in science and medicine have enabled us to make great strides in our struggle to prevent and control infectious diseases, we cannot fall prey to an illusory complacency. We must understand that pathogens—old and new—have ingenious ways of adapting to and breaching our armamentarium of defenses. We must also understand that factors in society, the environment, and our global interconnectedness actually increase the likelihood of the ongoing emergence and spread of infectious diseases. It is a sad irony that today we must also grapple with the intentional use of biological agents to do harm, human against human.

No responsible assessment of microbial threats to health in the twenty-first century, then, could end without a call to action. The magnitude and urgency of the problem demand renewed concern and commitment. We have not done enough—in our own defense or in the defense of others. As we take stock of our prospects with respect to microbial threats in the years ahead, we must recognize the need for a new level of attention, dedication, and sustained resources to ensure the health and safety of this nation—and of the world.