Summary

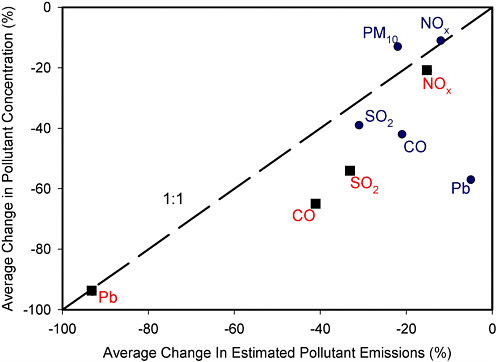

Over the past three decades, the nation has devoted substantial efforts and resources to protect and improve air quality through implementation of the Clean Air Act (CAA). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that the direct costs of this implementation have been as high as $20–30 billion per year. There is little doubt that these expenditures have helped reduce pollutant emissions despite the substantial increases in activities that produce these emissions (see Figure S-1). Although it is not possible to know what the exact concentrations of pollutant emissions might be in the absence of the CAA, it is reasonable to conclude that implementation of the act played an important role in lowering these emissions. Cost-benefit analyses have generally concluded that the economic value of the benefits to public health and welfare1 have equaled or exceeded the costs of implementation.

Despite substantial progress in improving air quality, the problems posed by pollutant emissions in the United States are by no means solved. Future economic and population expansions and the concomitant increased needs, for example, for electricity and transportation, will undoubtedly increase the potential for emissions. Consequently, additional effort will almost certainly be needed to maintain current air quality; even more effort will be needed to make further improvements. The CAA prescribes a com-

FIGURE S-1 Comparison of growth areas and emission trends. Note that the trends in the graph (except for aggregate emissions) did not change substantially in 1995; only the scale of the graph changed. SOURCE: EPA 2002a.

plex set of responsibilities and relationships among federal, state, tribal,2 and local agencies for implementing the CAA. This is essentially the nation’s air quality management (AQM) system.

CHARGE TO COMMITTEE

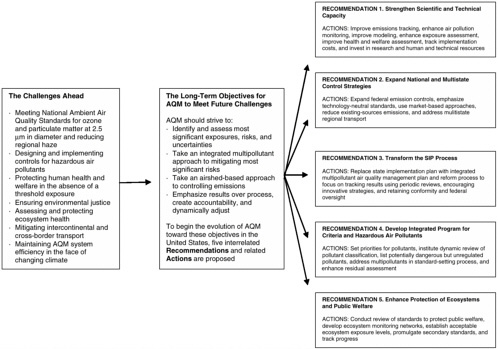

The Committee on Air Quality Management in the United States was formed by the National Research Council in response to a congressional request for an independent evaluation of the overall effectiveness of the CAA and its implementation by federal, state, and local government agencies. The committee was asked to develop scientific and technical recommendations for strengthening the nation’s AQM system. In response to its charge,3 the committee examined in detail the operation, successes, and limitations of the many components of the nation’s AQM system and developed a set of unanimous findings and recommendations, as discussed below and outlined in Figure S-2.

|

2 |

Hereafter, “state” will be used to denote both state and tribal authorities. |

|

3 |

See Chapter 1 for a discussion of the committee’s approach to carrying out its charge. |

FIGURE S-2 To meet the major challenges that will face air quality management (AQM) in the coming decade, the committee identified a set of overarching long-term objectives. Because immediate attainment of these objectives is unrealistic, the comm itteemade five interrelated recommendations to be implemented through specific actions.

THE CURRENT AQM SYSTEM

Two landmark events in 1970 helped to establish the basic framework for managing air quality in the United States: the enactment of the CAA Amendments and the creation of EPA. The CAA and its subsequent amendments (such as those in 1977 and 1990) endeavor to protect and promote public health and public welfare by pursuing the following goals:

-

Mitigate potentially harmful ambient concentrations of six so-called criteria pollutants: carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O3), particulate matter (PM), and lead (Pb).

-

Limit the sources of exposure to hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), also called “air toxics.”

-

Protect and improve visibility in wilderness areas and national parks.

-

Reduce emissions of substances that cause acid deposition, specifically sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides (NOx).

-

Curb use of chemicals that have the potential to deplete stratospheric ozone.4

The nation’s AQM system operates through three broad kinds of activities (Figure ES-1): (1) setting standards and objectives, (2) designing and implementing control strategies, and (3) assessing status and measuring progress. The committee’s detailed assessments of the strengths and limitations of these activities are presented in Chapter 2 (Setting Standards and Objectives), Chapter 3 (Implementation Planning), Chapter 4 (Mobile-Source Controls), Chapter 5 (Stationary-Source Controls), and Chapter 6 (Measuring Progress). Overall, the committee found that the AQM system has made substantial progress, especially in the following ways:

-

Setting National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for criteria pollutants, designing and implementing state implementation plans (SIPs) to comply with the NAAQS, and implementing other CAA programs to address hazardous air pollutants, acid rain, and other issues have all promoted enhanced technologies for pollution control and have contributed to substantial decreases in pollutant emissions.

-

Air quality monitoring networks have documented decreases in ambient concentrations of the criteria pollutants, especially in urban areas, and despite growth in power production and transportation uses. The NAAQS for sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide have

-

been largely attained. Monitoring networks have also documented a reduction in sulfate deposition in the eastern United States.

-

Economic assessments of the overall costs and benefits of AQM in the United States conclude that, even recognizing the considerable uncertainties, implementation of the CAA has had net economic benefits.

With regard to the three broad activities in AQM (Figure ES-1), the committee found the following:

Standard Setting

-

Standard setting, planning and control strategies for criteria pollutants and hazardous air pollutants have largely focused on single pollutants instead of potentially more protective and more cost-effective multipollutant strategies. Integrated assessments that consider multiple pollutants (ozone, particulate matter, and hazardous air pollutants) and multiple effects (health, ecosystem, visibility, and global climate change) in a single approach are needed.

-

Current risk assessment and standard-setting programs do not account sufficiently for all the hazardous air pollutants that may pose a significant risk to human health and ecosystems or for the complete range of human exposures both outdoors and indoors.

-

EPA’s current practice for setting secondary standards5 for most criteria pollutants does not appear to be sufficiently protective of sensitive crops and ecosystems.

Designing and Implementing Controls

-

Although pollutant concentrations have decreased, the federal, regional, and state emission-control programs implemented under the SIP process have not resulted in NAAQS attainment for ozone and particulate matter in many areas. In addition, the SIP process has become overly bureaucratic, places too much emphasis on uncertain emission-based modeling simulations of future air pollution episodes, and has become a barrier to technological and programmatic innovation.

-

Air quality models have often played a major role in designing air pollution control strategies. Much effort has gone into the development and improvement of these models; as a result, they are highly sophisticated. Limitations remain, however, in large part due to a lack of data to adequately evaluate their performance in specific applications for specific locations and an inability to rigorously quantify their uncertainty.

-

Progress has been made in recognizing and addressing multistate transport of air pollution, especially for ozone and atmospheric haze and their precursors, in some parts of the nation. However, transport issues need to be identified and addressed more proactively and the scope broadened to include international transport.

-

For mobile sources, regulations for light-duty vehicles, light-duty trucks, and fuel properties have greatly reduced emissions per mile traveled. Gaps remain, however, in the ability to monitor, predict, and control vehicular emissions, especially from nonroad vehicles, heavy-duty diesel trucks, and malfunctioning automobiles.

-

Emission reductions from stationary sources (for example, power plants and large factories) have also been substantial. However, most of the reductions have been accomplished through regulations on new facilities, while many older higher-emitting facilities continue to be a substantial source of emissions.

-

In recent years, emissions cap and trade has provided an effective mechanism for achieving stationary-source emission reductions at reduced costs. However, cap-and-trade programs have been limited to relatively few pollutants, and the process of revising caps and targets in response to new technical and scientific knowledge has been cumbersome.

Assessing Status and Measuring Progress

-

With the exception of continuous emissions monitoring at some large stationary sources, the nation’s AQM system lacks a comprehensive and quantitative program to confirm the emission reductions claimed to have occurred as a result of AQM.

-

The air quality network in the United States is a national resource but is nevertheless inadequate to meet important objectives, especially that of tracking regional patterns of pollutant concentrations, transport, and trends (see Figure S-3).

-

The AQM system has not developed a program to track health and ecosystem exposures and effects and to document improvements in health and ecosystem outcomes achieved from improvements in air quality. Ecosystem effects have not been reliably and consistently accounted for in cost-benefit analyses.

THE CHALLENGES AHEAD

Although the nation’s AQM system has been effective in addressing some of the most serious air quality problems, it has a number of limitations, as outlined above. In addressing how those limitations can best be remedied,

FIGURE S-3 Plot of the estimated relative trends in emissions versus ambient concentrations of various primary pollutants (PM10, NOx, SO2, Pb, and CO). Emission trends, which were derived from emission inventories, are shown along the xaxis, and the trends in average concentrations, which were derived from air quality monitoring networks, are shown along the y-axis. The squares are the relative trends in emissions and ambient concentrations for the 20-year period spanning 1983–2002 (except for PM10 emissions, which are for the trend period 1985–2002), and the circles are the relative trends for the 10-year period of 1993–2002. If the emission inventory trends were accurate and the nation’s air quality monitoring networks were able to accurately measure the average concentration of primary pollutants in the air overlying the United States, all the points on the graph would fall on the 1:1 (diagonal) line. However, the fact that most of the points on the graph do not fall on the 1:1 line indicates that the emission inventory trends are inaccurate and/or that the nation’s air quality network, which was initially designed to monitor urban pollution and compliance with NAAQS, has not been able to track trends in pollutant concentrations quantitatively across urban, suburban, and rural settings. Despite such uncertainty, it is important to note that the downward trend in ambient pollutant concentrations provides qualitative confirmation that pollutant emissions have been decreasing. SOURCE: Data from EPA 2003.

it is important to consider the major air quality challenges facing the nation in the coming decades. Seven major challenges are outlined below.

-

New Standards. Additional reductions in pollutant emissions will be required to meet the EPA 1997 standards for ozone and particulate matter and the 1999 regulations for regional haze. Improvements to the AQM system will be needed to best identify what emissions to reduce and to monitor the progress toward meeting new standards.

-

Toxic Air Pollutants. The human health risks from exposure to toxic pollutants remain significant and poorly quantified. A greater research effort that focuses on the sources, atmospheric distribution, and effects of most toxic air pollutants will be needed to address health risks and ensure adequate protection to the public.

-

Health Effects at Low Pollutant Concentrations. There is increasing evidence that there might not be an identifiable exposure concentration (threshold) for some criteria pollutants below which human health effects would cease to occur. A better understanding of the reducible (human-induced) and irreducible components of pollution, as well as the health and ecosystem impacts at low levels of exposure, is needed. Once improved scientific understanding is developed, it might be necessary to reconsider how to set standards to protect public health from pollutants for which thresholds can not be identified.

-

Environmental Justice. The CAA does not have any programs explicitly aimed at mitigating pollution effects that might be borne disproportionately by minority and low-income communities in densely populated urban areas. Addressing this need will require enhancing the science base for determining exposures of selected communities to air pollution and incorporating environmental equity concepts in the earliest stages of air quality planning. Native American tribes should be given help to develop and implement AQM programs for reasons of environmental justice and tribal self-determination.

-

Protecting Ecosystem Health. Although mandated in the CAA, the protection of ecosystems affected by air pollution has not received appropriate attention in the implementation of the act. A research and monitoring program is needed that can quantify the effects of air pollution on the structure and functions of ecosystems. That information can be used to establish realistic and protective goals, standards, and implementation strategies for ecosystem protection.

-

Multistate, Cross-Border, and Intercontinental Transport. Evidence is accumulating that shows that air quality in a specific area can be influenced by pollutant transport across multistate regions, national boundaries, and continents. To address multistate pollutant transport, the AQM system must improve the techniques for tracking and documenting pollutant

-

transport and develop more effective mechanisms for coordinating multistate regional air pollution control strategies. In addition, the nation should continue to pursue collaborative projects and enter into agreements and treaties with other nations to help minimize pollution transport to and from the United States.

-

AQM and Climate Change. The earth’s climate is warming. Although uncertainties remain, the general consensus within the scientific community is that this warming trend will continue or even accelerate in the coming decades. The AQM system will need to ensure that pollution reduction strategies remain effective as the climate changes, because some forms of air pollution, such as ground-level ozone, might be exacerbated. In addition, emissions that contribute to air pollution and climate change are fostered by similar anthropogenic activities, that is, fossil fuel burning. Multipollutant approaches that include reducing emissions contributing to climate warming as well as air pollution may prove to be desirable.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To meet the challenges of the coming decades and remedy current limitations, the committee identified a set of long-term, overarching objectives to guide future improvement of the AQM system. In the committee’s view, AQM should

-

Strive to identify and assess more clearly the most significant exposures, risks, and uncertainties.

-

Strive to take an integrated multipollutant approach to controlling emissions of pollutants posing the most significant risks.

-

Strive to take an airshed6-based approach by assessing and controlling emissions of important pollutants arising from local, multistate, national, and international sources.

-

Strive to emphasize results over process, create accountability for the results, and dynamically adjust and correct the system as data on progress are assessed.

Immediate attainment of these objectives is unrealistic. It would require a level of scientific understanding that has yet to be developed, a commitment of new resources that would be difficult to obtain in the short term, and a rapid transformation of the AQM system that is uncalled for in light of the system’s past successes. The committee proposes, therefore, that the AQM system be enhanced so that it steadily evolves towards meeting these

objectives. In that spirit, the committee makes five interrelated recommendations, to be implemented in concert through some 30 specific actions described in this report.

Recommendation One

Strengthen scientific and technical capacity to assess risk and track progress.

Improving the nation’s AQM system will depend heavily on reassessing and investing in relevant scientific and technical capacity to help evolve the AQM system to one that can focus on risk in priority setting and on performance in measuring progress. Without the enhancement of the nation’s scientific and technical capacity, implementation of the other four recommendations will be more difficult. The most critical actions are

-

Improve emissions tracking, including new emissions monitoring techniques and regularly updated and field-evaluated inventories.

-

Enhance air pollution monitoring, including new monitoring methods, expanded geographic coverage, improved trend analysis, and enhanced data accessibility.

-

Improve modeling, including enhanced emission and air measurement programs to provide data for model inputs and model evaluation and continued development of shared modeling resources.

-

Enhance exposure assessment, including improved techniques for measuring personal and ecosystem exposure and designing strategies to control the most significant sources of ambient, hot-spot,7 and indoor exposures.

-

Develop and implement a system to assess and monitor human health and welfare effects through the identification of indicators capable of characterizing and tracking the effects of criteria pollutants and hazardous air pollutants and the benefits of pollution control measures and their sustained use in assessments, such as the 2003 EPA Draft Report on the Environment.

-

Continue to track implementation costs by supporting the Pollution Abatement Cost and Expenditure (PACE) survey and conducting detailed

-

and periodic examinations of actual costs incurred in a subset of past regulatory programs, including comparisons of actual costs to the costs predicted by various parties prior to adoption of regulations.

-

Invest in research to facilitate multipollutant approaches that targets the most significant risks, including enhanced research into the full range of ambient, hot-spot, and indoor exposures and their potential risks.

-

Invest in human and technical resources through programs and incentives to attract and train a diverse corps of scientists and engineers contributing to AQM and the development of an environmental extension service.

Recommendation Two

Expand national and multistate performance-oriented control strategies to support local, state, and tribal efforts.

The role of EPA in establishing and implementing national and multistate emission-control measures should be expanded so that states can focus their efforts on local emission concerns. The most critical actions are

-

Expand federal emission-control measures especially for nonroad mobile sources (for example, aircraft, ships, locomotives, and construction equipment), area sources (relatively small dispersion), and building and consumer products. Development of these measures should actively involve states, local agencies, and stakeholders and allow for continued control-measure innovation at the state and local level.

-

Emphasize technology-neutral standards for emission control. Whenever practical, control measures should cap the total emissions from a given source or group of sources, as opposed to limiting the rate of emissions per unit of resource input or product output. In cases where a cap is not practical, standards should be set that promote improved technologies rather than being tied to a single technology and that are stringent enough to offset projected emission increases caused by future growth in economic activity.

-

Use market-based approaches whenever practical and effective through the expanded use of approaches, such as the acid rain SO2 emissions cap-and-trade program, that have the potential to be highly effective and realize substantial cost savings. Such programs must incorporate continuous emissions monitoring to ensure that emission goals are met and be designed to identify and minimize geographic and temporal disparities in results. Expansion to new industrial sectors will require enhanced continuous emission-monitoring systems, technologies to ensure that required re-

-

ductions are achieved, and ambient monitoring to establish that the program does not inadvertently result in geographic and temporal disparities in results.

-

Reduce emissions from existing facilities and vehicles, to the extent practical by promulgating standards for sources regardless of their age, status, or fuel. Older stationary sources and mobile nonroad sources are of particular concern.

-

Address multistate transport problems by providing EPA with greater statutory responsibility to assess multistate air quality issues on an ongoing basis and the regulatory authority to deal with them in a regional context. Constitutionally, interstate environmental rules and regulations must be based on federal authority, but EPA has not been given sufficient tools under the CAA to address the multistate aspects of most air quality problems.

Recommendation Three

Transform the SIP process.

Implementation planning at the state and local levels should be changed to place greater emphasis on performance and results and to facilitate development of multipollutant strategies. Critical actions include

-

Transform the SIP into an AQM plan. Each state should be required to prepare an air quality management plan (AQMP) that integrates the relevant air quality measures and activities into a single, internally consistent plan. An evolution of the SIP process to an AQMP approach should involve the following:

-

Given the similarity of sources, precursors, and control strategies, the AQMP should encompass all criteria pollutants in an integrated multipollutant plan.

-

EPA should identify key hazardous air pollutants that have diverse sources or substantial public health impacts. These pollutants should be included in an integrated multipollutant control strategy and addressed in each state’s AQMP.

-

The scope of the AQMP should explicitly identify and propose control strategies for air pollution hot spots and situations where disadvantaged groups may be disproportionately exposed and should provide incentives to implement the strategies.

-

Given the current statutory requirements and rules associated with the SIP, it might be necessary to implement this recommendation in stages and provide incentives to facilitate the transition to an AQMP approach.

-

-

Reform the planning and implementation process by

-

Encouraging regulatory agencies to concentrate their resources on tracking and assessing the performance of the strategies that have been implemented rather than on preparing detailed documents to justify the effectiveness of strategies in advance of their implementation.

-

Carrying out a formal and periodic process of review and reanalysis of the AQMP to identify and implement revisions to the plan when progress toward attainment of standards falls below expectations or when conditions change sufficiently to invalidate the underlying assumptions of the plan. Given the large contributions of federal and multistate measures to the success of any plan, it is essential that this review process be collaborative and include all relevant federal and state agencies.

-

Encouraging the development and testing of innovative strategies and technologies by not requiring predetermined and agreed-upon benefits for every strategy but periodically evaluating their effectiveness.

-

Retaining the federal requirement for conformity between air quality planning and transportation planning. Conformity could be improved by mandating greater consistency between the data, models, and time frames used in air quality and transportation plans.

-

Continuing to require that states implement agreed upon strategies, ensure private-sector compliance, and are held accountable for failure to meet the AQMP commitments through federally mandated sanctions.

-

Recommendation Four

Develop an integrated program for criteria pollutants and hazardous air pollutants.

The time has come for the nation’s AQM system to begin the transition toward an integrated, multipollutant approach that targets the most significant exposures and risks. The critical actions include

-

Develop a system to set priorities for hazardous air pollutants by expanding the approach embodied in EPA’s urban air toxics program. As proposed in Recommendation Three, a few hazardous air pollutants, because of their diverse sources, ubiquitous presence in the atmosphere, or exceptionally high risk to human health and welfare, might warrant treatment similar to criteria pollutants and be included in AQMPs.

-

Institute a dynamic review of pollutant classification, and reclassify and revise priorities for criteria pollutants and hazardous air pollutants accordingly.

-

List potentially dangerous but unregulated air pollutants for regulatory attention. Determine whether there are sufficient data on adverse impacts, chemical structure, and potential for population exposure and identify whether some level of regulatory response would be prudent and appropriate.

-

Address multiple pollutants in the NAAQS review and standard-setting process by beginning to review and develop NAAQS for related pollutants simultaneously.

-

Enhance assessment of residual risk by performing an increased number of assessments in the years to come and by attempting to include in the assessments other major sources of the same chemicals.

Recommendation Five

Enhance protection of ecosystems and other aspects of public welfare.

Many of the programs and actions undertaken in response to the CAA have focused almost entirely on the protection of human health. Further efforts are needed to protect ecosystems and other aspects of public welfare. The critical actions include

-

Completion of a comprehensive review of standards to protect public welfare.

-

Develop and implement networks for comprehensive ecosystem monitoring to quantify the exposure of natural and managed resources to air pollution and the effects of air pollutants on ecosystems.

-

Establish acceptable exposure levels for natural and managed ecosystems by evaluating data on the effects of air pollutants on ecosystems at least every 10 years.

-

Promulgate secondary standards where needed that take the appropriate form. For example, in some cases a standard based on the amount of a pollutant that is deposited on the earth’s surface over a particular area may be more appropriate than a standard based on the atmospheric concentration of that pollutant. Allow for consideration of regionally distinct standards.

-

Track progress toward attainment of secondary standards by using the aforementioned monitoring of ecosystem exposure and response.

MOVING FORWARD

Because the nation’s AQM system has been effective in many aspects over the past three decades, much of the system is good and warrants retaining. Thus, the recommendations proposed here are intended to evolve

the AQM system incrementally rather than to transform it radically. The recommendations are also not intended to deter current ongoing AQM activities aimed at improving air quality. Indeed, even as these recommendations are implemented, there can be little doubt that important decisions to safeguard public health and welfare should continue to be made, often in the face of scientific uncertainty. Moreover, new opportunities and approaches for managing air quality will appear. These include addressing pollution problems in multiple environmental media, such as air and water, taking advantage of new technologies, and undertaking pollution prevention activities rather than controlling air pollutants after they have been produced.

Implementation of the recommendations will require the development of a detailed plan and schedule of steps. The committee urges EPA to convene an implementation task force from the key parties to prepare a plan of action and an analysis of legislative actions, if any are needed.

Implementation of the recommendations will also require additional resources. Although these resources are not insignificant, they should not be overwhelming. For example, consider the costs associated with air quality research and monitoring. Even a doubling of the approximate $200 million in EPA funds currently dedicated to air quality monitoring and research would represent about 1% of annual expenditures nationwide for complying with the CAA. Such resources are even smaller when compared with the costs imposed by the deleterious effects of air pollution on human health and welfare.

Implementation of the recommendations will require a commitment by all parties to stages of implementation over several years. As that transition occurs, it is important that action on individual programs to reduce emissions continues to maintain progress toward cleaner air.

The full complement of scientific and engineering disciplines will need to be prepared to take up the substantial challenges embodied in these recommendations. Given the opportunity, the committee believes that the scientific and engineering communities can provide the human resources and technologies needed to underpin an enhanced AQM system and to achieve clean air in the most expeditious and effective way possible.