2

Social, Health, and Economic Consequences of Underage Drinking*

Ralph Hingson and Donald Kenkel

Since 1988, it has been illegal for someone under the age of 21 to drink alcohol in all 50 states. This was a reversal of an earlier policy trend: In the wake of the 1972 constitutional amendment that extended the right to vote to 18-year-olds, 29 states had also lowered their legal drinking ages. Higher traffic fatalities and other problems experienced in those states were part of the impetus for the national drinking age of 21. This national drinking age has been a clear policy success (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1987; Jones, Pieper, and Robertson, 1992; Shultz et al., 2001; Wagenaar and Toomey, 2002). However, as we will discuss, many underage youth continue to consume alcohol and to experience alcohol related problems.

In the remaining sections of this chapter, we review evidence on the health and social consequences of underage drinking. Research from different perspectives—in terms of disciplines, data, and methods—helps to document these consequences. High-quality data document some of the immediate consequences of underage drinking, such as the number of traffic fatalities that involve underage drinkers. Self-reported data further suggest that a variety of health risks are associated with underage drinking. An intriguing line of emerging research suggests that age of drinking initiation may be a risk factor for adult drinking problems. These patterns should be

viewed with some caution, however, both because of the shortcomings of self-reported data and because of the difficulty of determining the extent to which underage drinking causes other health risks rather than simply being associated with these risks. We then explore research on the economic consequences of underage drinking, including both immediate health care expenditures and earnings losses experienced by underage drinkers over their entire life-course. Finally, we present a brief discussion and conclusion about the program and policy implications of the social and economic consequences of underage drinking.

UNDERAGE ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Despite the legal drinking age of 21 in all states, according to the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) (N = 68,929 age 12 and over, 32,002 ages 12 to 20, response rate 67 percent), 28.5 percent of persons ages 12 to 20 reported using alcohol in 2001 at some point in the 30 days prior to the survey (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] 2002). Projected onto the U.S. population that age, 10.1 million persons ages 12 to 20 drank in the past 30 days. Nearly 6.8 million, or 19 percent, were binge drinkers (consumed 5 or more drinks on an occasion at least once in the past 30 days). More than 2 million, or 6 percent, drank 5 or more drinks on at least 5 occasions in the past 30 days. Since 1980, the average age people began drinking has dropped from 17.4 to 15.9 years old (SAMHSA, 2002).

Males ages 12 to 20 were more likely to report binge drinking in the past month than their female peers (22 percent versus 16 percent). Binge drinking was reported by 21.7 percent of underage whites and 18.5 percent of underage American Indians or Alaska Natives, but only by 10.7 percent of underage Asians and 10.5 percent of underage blacks.

Among persons under age 21, those ages 18 to 20 were the most likely to drink. Just over half drank in the past month, 30 percent reported binge drinking at least once in the past 30 days, and 13 percent reported consuming 5 or more drinks on at least 5 occasions in the past 30 days.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Youth Risk Behavior Survey examined a national random sample of high school students (Grunbaum et al., 2002), nearly all of whom are ages 14 to 18. Completed for CDC in 2001, the survey used a three-stage probability sample to obtain 13,601 completed questionnaires from a representative sample of high school students in public and private schools in the United States, with a response rate of 65 percent. Large numbers in that age group also drink and drink heavily. That survey showed 47 percent of high school students drank alcohol in the past month. Projected to the U.S. high school student population, 7,018,364 drank alcohol in the past month. Thirty-

four percent, or more than 5 million, drank 5 or more drinks within a two-hour period on at least one occasion in the previous month. Seventy-eight percent, or more than 11.6 million, had consumed alcohol at some point in their lives and 29 percent, or 4.3 million, reported starting to drink before age 13. Thirteen percent, or 1.9 million, drove after drinking in the past 30 days and 31 percent, or 4.6 million, rode with a drinking driver. Five percent, or more than 700,000, drank at school in the past 30 days.

For some, heavy drinking begins even before high school. In 2001, according to the NHSDA, 2 percent of 12-year-olds and 3 percent of 13-year-olds consumed 5 or more drinks on at least one occasion in the past 30 days.

HEALTH RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH UNDERAGE DRINKING

Not only is drinking by persons underage an illegal activity, but persons that age who drink are more likely than those who do not to engage in behaviors that pose a risk to their health and the health of others.

Deaths Associated with Underage Drinking

Traffic Crash Deaths

The greatest single mortality risk posed by underage drinking is traffic crashes. Traffic crashes are the leading cause of death in the United States for persons ages 4 to 34 (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA] 2002). According to the Fatality Analysis Reporting System of the NHTSA, in 2001, 39 percent of traffic deaths by those ages 16 to 20 involved a driver, passenger, or pedestrian who had been drinking (2,365/ 6,051) (NHTSA, 2001). Of course it is possible that some of the drinking drivers in those fatal crashes were 21 or older. In 2001, 1,884 drivers under age 21 in fatal motor vehicle crashes had positive blood alcohol levels, including 45 of whom were under age 16. Of those drivers, 1,109 died in those crashes. Many persons other than the drinking driver were also killed in those crashes. In 2001, 1,099 persons other than drinking drivers under age 21 died in fatal crashes when those drivers under age 21 were involved. Six hundred thirty were under age 21, and most of them (587) were passengers either in the vehicle driven by or struck by the drinking driver under age 21.

Epidemiologic research comparing drivers in single-vehicle fatal crashes with drivers operating motor vehicles at similar times on the same roadways who were not involved in fatal crashes has revealed that each 0.02 percent increase in blood alcohol level nearly doubles the risk of single-vehicle fatal crash involvement and that the risk of death increases with each drink

more for younger drivers than it does for drivers above the age of 21 (Zador, 1991). A more recent national analysis found that in all age and gender groups, there was at least an 11-fold increased risk of single-vehicle fatal crash involvement at a blood alcohol level of 0.08 percent (the legal limit for intoxication for adults in most states). However, for male drivers ages 16 to 20, there was a 52-fold increased single-vehicle fatal crash risk (Zador, Krawchek, and Voas, 2000).

The National Survey of Drinking and Driving conducted for NHTSA in 1999 (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2000) reported that 2 percent of 16- to 20-year-old drivers drove within two hours of drinking in the past month. Though this percentage is substantially lower than the 12 percent reported by all drivers ages 16 and older, drivers ages 16 to 20 drove 12 million times in the preceding year within two hours of drinking (95 percent CI 4, 119). Those drinking driving trips averaged 11 miles in length compared to 14 for all drinking driving trips among drivers ages 16 and older. Particularly disturbing, however, was that when NHTSA calculated the average blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of drivers during their most recent drinking driving trip—based on weight, hours of drinking, gender, volume of consumption, length of drinking episode—and time since last drink, the average calculated BAC for 16- to 20-year-old drivers was 0.10 percent, more than 3 times the level for drivers of all ages and at or above the legal limit for adult drivers in every state. A 170-pound man would have to consume 5 drinks in an hour on an empty stomach to reach a blood alcohol level of 0.10 percent. Furthermore, 40 percent of those 16-to 20-year-olds were driving with another passenger in the vehicle during their most recent drinking driving trip, thereby risking not only their own life but the lives of others. Four percent were driving with children under the age of 15.

Of note, 44 percent of the 16- to 20-year-old drinking drivers believed they were driving at levels that exceeded the legal limit. In other words, nearly half reported engaging in behavior they knew was illegal. Of parallel concern, it is illegal for all persons under age 21 to drive after any drinking, and 56 percent, a majority, who did so did not recognize that they were engaging in illegal behavior. Studies of states that adopted laws making it illegal for persons under 21 to drive after drinking relative to other states have achieved 18 percent declines in driving after any drinking, 23 percent declines in driving after 5+ drinks (Wagenaar, 2001), and 21 percent decline in the type of fatal crash most likely to involve alcohol (single vehicle at night) among drivers under 21 (Hingson, Heeren, and Winter, 1994). In studies where teen awareness of the law has been heightened, significantly greater declines in alcohol-related crashes among drivers under 21 have been recorded (Blomberg, 1992).

Other Unintentional Injury Deaths

Of course, traffic fatalities are not the only type of injury death that has been linked to alcohol. In 2000 there were 15,733 unintentional injury deaths among persons under 21. Of those, 8,797 were traffic deaths and 6,936 were from other causes (e.g., drowning, burns, falls) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2002). A review of more than 300 medical examiner studies in the United States over a 20-year period (Smith, Branas, and Miller, 1999) revealed that the percentage of nontraffic unintentional injury deaths that test positive for alcohol closely corresponds to the percentage of motor vehicle deaths that are alcohol related: 38 percent versus 40 percent. Among persons under age 21, 34 percent of unintentional traffic deaths (2,956/8,797) are alcohol related. If 34 percent of unintentional injury deaths other than motor vehicle deaths among persons under 21 were alcohol related, then 2,358 unintentional injury nontraffic deaths among persons under 21 were alcohol related.

Intentional Injury Deaths

Among adults alcohol was also found to be present in 47 percent of homicides and 29 percent of suicide deaths (Smith et al., 1999). In 2000 there were 4,314 homicides and 2,905 suicides among those under the age of 21. It has been reported that among persons under 21, 36 percent of homicide deaths, 12 percent of male suicide deaths, and 8 percent of female suicide deaths were alcohol related (Levy, Miller, and Lox, 1999). If correct, more than 1,500 homicides and 300 suicides in 2000 among persons under 21 were alcohol related.

Self-Reports of Health Risks Associated with Underage Drinking

Drinking, especially frequent heavy drinking, has been associated with a variety of health risks behaviors among adolescents. An association, of course, does not mean alcohol use causes the other risky behaviors, but it can certainly increase risks to health. For example, if frequent heavy drinkers drive after drinking more often, their risk of traffic crash involvement is higher. If they are also less likely to wear safety belts, then their risk of being injured or killed in those crashes is also higher.

When asked about their drinking in the past 30 days, 28 percent of high school students responding to the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Grunbaum et al., 2002) reported at least one occasion when they drank 5 or more drinks. Nine percent reported one such occasion. Six percent reported two occasions, another 6 percent reported 3 to 5 and 7 percent drank 5+ drinks on at least 6 occasions. Nine percent of the

sample drank in the past 30 days, but never as many as five drinks at one sitting. Drinkers were more likely than nondrinkers to engage in a variety of behaviors that pose a risk to health, and the more frequently respondents reported heavy drinking (5 or more on an occasion), the greater their likelihood of engaging in behaviors that pose a risk to health.

Risks in Traffic

As Tables 2-1a and 2-1b show, a greater percentage of those who drank compared to those who never drank engaged in behaviors in traffic that increased their risk of being in a motor vehicle crash and being injured if in a crash. Moreover, the more frequently respondents drank 5 or more drinks, the greater the percentage who engaged in risky behaviors in traffic. Only 3 percent of respondents who never drank said they never wore safety belts compared to 15 percent of those who drank 5+ at least 6 times in the past month (frequent heavy drinkers). Only 14 percent of those who never drank rode with a driver who had been drinking, compared to 80 percent of frequent heavy drinkers. Of course, none who never drank drove after drinking, while 41 percent of frequent heavy drinkers did so. Twenty-two percent of respondents said they rode on a motorcycle and 63 percent on a

TABLE 2-1a Traffic Risks According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Of Motorcyclists Never Wear a Helmet |

27% |

29% |

33% |

36% |

42% |

45% |

|

Of Bicyclists Never Wear a Helmet |

73% |

81% |

86% |

88% |

89% |

92% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-1b Traffic Risks According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never |

Drank Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Never Wear Seat Belt |

3% |

3% |

5% |

7% |

10% |

15% |

|

Ride with Drinking Driver |

14% |

31% |

50% |

60% |

69% |

80% |

|

Drive after Drinking |

0% |

11% |

13% |

32% |

43% |

41% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

bicycle in the past 30 days. Of those who never drank, 27 percent said they never wore helmets on motorcycles and 73 percent said they never wear bicycle helmets. In contrast, among frequent heavy drinkers, 45 percent never wear motorcycle helmets and 92 percent never wear bicycle helmets.

Weapons and Violence

Compared to nondrinkers, a greater percentage of drinkers and especially frequent heavy drinkers carried weapons, engaged in physical violence (Tables 2-2a and 2-2b), felt sad or hopeless, attempted suicide (Table 2-3), engaged in other psychoactive drug use (Tables 2-4a, 2-4b, and 2-4c), had sex at an earlier age, had more partners, and were more likely to have unprotected sex and to have been or gotten someone pregnant (Tables 2-5a, 2-5b, and 2-5c). Among nondrinkers, 10 percent carried a weapon and 3 percent a gun in the past 30 days. Forty-four percent of frequent heavy drinkers carried a weapon and 22 percent a gun in the past 30 days. Not only were the frequent heavy drinkers more likely to carry weapons and

TABLE 2-2a Weapons and Violence According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Carry Weapon |

10% |

18% |

22% |

26% |

28% |

44% |

|

Carry Gun |

3% |

4% |

8% |

8% |

11% |

22% |

|

Weapon at School |

3% |

6% |

9% |

10% |

13% |

20% |

|

In a Fight Past Year |

23% |

35% |

43% |

46% |

52% |

62% |

|

Injured in a Fight Past Year |

2% |

4% |

7% |

6% |

7% |

13% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-2b Weapons and Violence According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Fight at School Past Year |

9% |

13% |

17% |

17% |

19% |

74% |

|

Threatened at School |

6% |

8% |

11% |

12% |

12% |

19% |

|

Boy/Girlfriend Hit/Slapped Past Year |

6% |

10% |

11% |

15% |

17% |

23% |

|

Forced to Have Sex |

5% |

8% |

9% |

12% |

13% |

18% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-3 Depressed Mood and Suicidal Behavior According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Felt Sad or Hopeless |

24% |

34% |

36% |

40% |

36% |

40% |

|

Ever Attempted Suicide |

4% |

9% |

10% |

15% |

14% |

18% |

|

Injured in a Suicide Attempt |

1% |

2% |

3% |

5% |

5% |

9% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-4a Substance Use According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Used Marijuana at School Past 30 Days |

1% |

5% |

8% |

12% |

17% |

27% |

|

Ever Used Cocaine |

3% |

7% |

14% |

20% |

28% |

43% |

|

Cocaine Use Past 30 Days |

0% |

2% |

6% |

8% |

14% |

26% |

|

Ever Sniff Glue |

6% |

14% |

17% |

21% |

24% |

32% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-4b Substance Use According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Ever Used Heroin |

<1% |

1% |

3% |

6% |

7% |

15% |

|

Ever Used Methamphetamine |

2% |

6% |

13% |

29% |

27% |

37% |

|

Ever Used Steroids |

1% |

3% |

5% |

9% |

11% |

18% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-4c Substance Use According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Ever Inject Drugs |

<1% |

1% |

2% |

4% |

5% |

13% |

|

Past Year Offered Drugs at School |

19% |

32% |

37% |

42% |

48% |

57% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-5a Sexual Risk Behaviors According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Past 30 Days Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Ever Had Sex |

34% |

56% |

62% |

71% |

74% |

87% |

|

Sex Before Age 13 |

5% |

8% |

9% |

10% |

11% |

18% |

|

Sex with 6+ Partners |

4% |

9% |

9% |

13% |

17% |

31% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2001). |

||||||

TABLE 2-5b Sexual Risk Behaviors According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Past 30 Days Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

3+ Sex Partners Past 3 Months |

2% |

4% |

5% |

8% |

10% |

20% |

|

Alcohol or Drugs Before Last Sexual Intercourse |

3% |

9% |

16% |

23% |

36% |

52% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2001. |

||||||

TABLE 2-5c Sexual Risk Behaviors According to Frequency of Drinking 5+ Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Past 30 Days Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Birth Control Last Sex |

83% |

85% |

88% |

86% |

83% |

82% |

|

Been/Gotten Someone Pregnant |

5% |

7% |

7% |

11% |

11% |

19% |

|

Used Condom Last Sex |

63% |

61% |

64% |

62% |

57% |

54% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2001. |

||||||

guns, they were more likely to be in fights in the past year than nondrinkers (62 percent versus 23 percent) and in fights at school (7 percent versus 9 percent). Not surprisingly, they were more likely to have been injured in a fight in the past year (13 percent versus 2 percent) and to feel unsafe or threatened at school (1 percent or 19 percent, respectively, versus 6 percent of nondrinkers).

Twenty-three percent of frequent heavy drinkers reported being hit/ slapped by a boyfriend or girlfriend in the past year, compared to 6 percent of nondrinkers. Eighteen percent of the frequent heavy drinkers said they

were forced to have sex in the past year, compared to 5 percent of nondrinkers.

Suicidal Behaviors

Frequent heavy drinkers were more likely to report feeling helpless or sad than nondrinkers (40 percent versus 18 percent), to report suicide attempts in the past year (18 percent versus 4 percent), and to have been injured in a suicide attempt (9 percent versus 1 percent).

Tobacco and Illicit Drugs

Compared to nondrinkers, frequent heavy drinkers were more likely to have used tobacco products: cigarettes (94 percent versus 46 percent), snuff (32 percent versus 2 percent), and cigars (51 percent versus 4 percent). They were dramatically more likely in the past 30 days than nondrinkers to have used marijuana (73 percent versus 7 percent), to have used cocaine (26 percent versus 0 percent), to have sniffed glue (32 percent versus 2 percent), and to have used heroin (15 percent versus <1 percent), methamphetamines (37 percent versus 2 percent), steroids (18 percent versus 2 percent), and illegal injected drugs (13 percent versus <1 percent). First exposure to drugs began at a younger age among frequent heavy drinkers, with 37 percent using marijuana before age 13, compared to only 4 percent of nondrinkers.

A recent analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AdHealth, N = 4,831) revealed that the proportion of persons who use alcohol and tobacco both steadily increase during each consecutive year of adolescence and young adulthood (Jackson, Sher, Cooper, and Wood, 2002). Prior alcohol use more strongly predicted tobacco use than the reverse. In other words, initiation of smoking was a function of prior drinking more so than drinking was a function of prior smoking. The disinhibitory effects of alcohol may reduce resistance to smoking and lead to initiation of use (Sheffiman and Balabanis, 1995).

Although the exact mechanism by which drinking increases the likelihood of smoking has yet to be determined, the findings suggest that the negative consequences of early drinking include heavier smoking and the attendant health consequences of that heavier smoking.

Kandel, Yamaguchi, and Chen (1992) and Kandel and Yamaguchi (1993) analyzed drug use behavior among a random sample of New York high school students and identified a clear sequential pattern of drug involvement with the earliest stages involving use of either alcohol or cigarettes. In this sequence of use, alcohol was generally the drug of first use among males, whereas cigarette and tobacco use most often preceded use of marijuana and other drugs among females. Subsequent stages involved use

of marijuana and then other illicit and/or prescribed drugs. For example, use of marijuana typically preceded use of crack.

Morral, McCaffrey, and Paddock (2002) have published an analysis of the U.S. Household Survey of Drug Use to test a theory of marijuana use as a “gateway” to the use of other drugs. Their analyses did not disprove a gateway effect, but instead demonstrated another plausible alternative. A general drug use propensity may contribute to both marijuana use and the use of other drugs. Whether such an alternative explanation also could explain the association between alcohol and later marijuana and other illicit drug use has yet to be tested.

Sexual Behaviors

According to the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Grunbaum et al., 2002), frequent heavy drinkers relative to nondrinkers were also more likely to have had sexual intercourse (87 percent versus 34 percent), sex before age 13 (18 percent versus 5 percent), and sex with at least 6 different partners (31 percent versus 4 percent), and sex with at least 3 partners in the past month (20 percent versus 2 percent). Given their heavier drinking and drug use, frequent heavy drinkers not surprisingly were more likely than nondrinkers to have used alcohol or drugs prior to their last intercourse (52 percent versus 3 percent). Despite their far greater frequency of sexual activity with multiple partners, frequent heavy drinkers were no more likely to use birth control during their last sex (82 percent versus 83 percent) and were less likely to have used a condom (54 percent versus 63 percent). Frequent heavy drinkers were more likely to report having been pregnant or causing someone else to become pregnant (19 percent versus 5 percent) (Grunbaum et al., 2002).

Adolescents in other surveys report they were more likely to have unplanned sexual intercourse when they or a potential partner had been drinking (Strunin and Hingson, 1992). Moreover, young persons who are sexually active are more likely to have unprotected sex when they have intercourse after drinking than when they have intercourse when they have not been drinking (Strunin and Hingson, 1992; Hingson, Strunin, Berlin, and Heeren, 1990; Leigh and Stall, 1993; Stall, McResnick, Wiley, Coates, and Ostrow, 1996).

These findings are important because annually more than 900,000 adolescents become pregnant and most teen pregnancies are unplanned (Henshaw, 1998). Furthermore, adolescents are overrepresented in the nearly 1 million cases of sexually transmitted infection, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis (CDC, 1999), which in turn heighten risk of HIV infection. To date in the United States, 138,153 AIDS cases among 13-to 29-year-olds have been reported (U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, 2000), with most infected during their adolescent years (CDC, 2001).

Academic Performance

Finally, the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Grunbaum et al., 2002) reveals that persons who never drank were more likely to report receiving mostly A grades—29 percent compared to 21 percent who drank but never 5 or more drinks at a time, compared to only 12 percent of those who drank 5+ drinks on at least 6 occasions in the past month (Table 2-6). Persons who never drank were also less likely to report receiving mostly Ds and Fs—5 percent compared to 7 percent who drank but not 5 or more at a time, and 15 percent of those who drank 5 or more drinks on at least 6 occasions in the past 30 days. As we will discuss later in this chapter, if alcohol use contributes to poorer academic performance in adolescence, the economic consequences may extend into adult life.

Age of Drinking Onset and Alcohol-Related Health Risks

Not only are adolescents who drink heavily more likely to engage in behaviors that pose a risk to their health, but the younger adolescents are when they begin drinking alcohol, the more likely they are to experience alcohol related problems both during adolescence and in adulthood, including a higher frequency of drinking (Samson, Maxwell, and Doyle, 1989; Gruber, DiClemente, Anderson, and Lodico, 1996), heavier drinking (Barnes, Welte, and Dintcheff, 1992; Hingson, Heeren, Jamanka, and Howland, 2000), alcohol abuse (DeWit, Adlaf, Offord, and Ogborne, 2000), alcohol dependence (DeWit et al., 2000; Grant and Dawson, 1997; Chou and Pickering, 1992), alcohol misuse (Hawkins et al., 1997), alcohol related unintentional injuries (Gruber et al., 1996; Hingson et al., 2000;

TABLE 2-6 Academic Performance According to Frequency of 5 or More Drinks on an Occasion in the Past 30 Days

|

|

Never Drank |

Drank Not 5+ |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6+ |

|

N = |

7,228 |

2,187 |

1,248 |

840 |

845 |

891 |

|

Grades Mostly |

||||||

|

A’s |

29% |

21% |

17% |

15% |

16% |

12% |

|

B’s |

40% |

40% |

40% |

39% |

36% |

34% |

|

C’s |

22% |

27% |

31% |

33% |

32% |

34% |

|

D’s |

4% |

6% |

6% |

7% |

9% |

10% |

|

F’s |

1% |

1% |

1% |

2% |

3% |

5% |

|

SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2001. |

||||||

Hingson, Heeren, Levenson, Jamanka, and Voas, 2002), and getting into fights after drinking (Hingson, Heeren, and Zakocs, 2001). These associations consistently have been found in nationally representative samples of adults in the United States (Hingson et al., 2000; Grant and Dawson, 1997; Chou and Pickering, 1992; Hingson et al., 2002; Hingson et al., 2001), Ontario (DeWit et al., 2000), and New York (Barnes et al., 1992), as well as in national and convenience samples of college undergraduates (Samson et al., 1989) and public high school students (Gruber et al., 1996; Hawkins et al., 1997). Although most studies used cross-sectional designs, Hawkins and colleagues (1997) conducted a longitudinal study following a class of fifth graders for seven years and found similar associations, as did Chassin, Pitts, and Prost (2002), who followed a cohort for eight years whose average age at baseline had been thirteen.

Analyses of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiology Survey (NLAES) have revealed that those with a younger age of drinking onset are more likely to experience alcohol dependence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In 1992 a random sample of more than 42,000 adults nationwide were surveyed in person by the U.S. Census Bureau, with a response rate of 90 percent. Among both males and females, persons with and without a family history of alcoholism, and persons who began drinking prior to age 14, were at least 3 times more likely than those who waited until age 21 to begin drinking to experience alcohol dependence (Grant, 1998). More than 40 percent of those who began drinking prior to age 14 experienced dependence at some point in their lives.

Subsequent analyses of the NLAES reveal that even after controlling for history of alcohol dependence, those who began drinking at younger ages are more likely to drink heavily (5 or more drinks on an occasion) with greater frequency (Hingson et al., 2000) (Table 2-7).

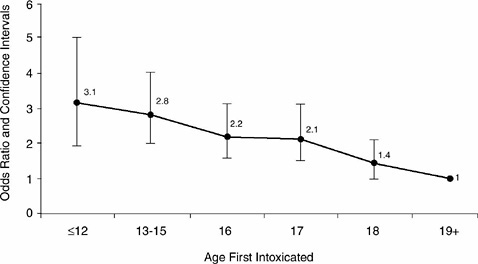

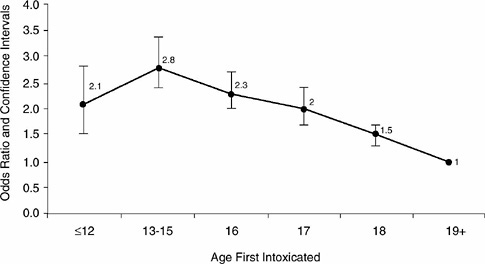

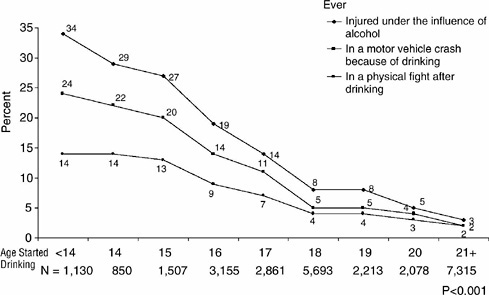

Furthermore, compared to persons who waited until they were 21 years or older, those who started at age 14 or younger were 12 times more likely to be unintentionally injured while under the influence of alcohol (Hingson et al., 2000), 7 times more likely to be in a motor vehicle crash after drinking (Hingson et al., 2002), and at least 10 times more likely to be in a physical fight after drinking (Hingson et al., 2001) (Figures 2-1 and 2-2). The significant relations between starting to drink at a younger age and these alcohol related injury and trauma outcomes persisted even after controlling for history of alcohol dependency, frequency of heavy drinking, years of drinking, age, gender, race/ethnicity, history of cigarette smoking, and illicit drug use.

These relationships were found ever in the respondent’s lifetime and for the year prior to the survey. Because the average NLAES respondent was

TABLE 2-7 Adjusted Odds Ratios Frequency of Heavy Drinking Occasions According to Age Started Drinking

|

|

Past Year Drank Heavily at Least Once Per Week |

||||||||

|

Age of Onset |

Drink 5+ on an Occasion |

Drank to Intoxication |

Lifetime Period of Heaviest Drinking Drank 5+ Daily |

||||||

|

|

OR |

95% |

CI |

OR |

95% |

CI |

OR |

95% |

CI |

|

<14 |

1.44 |

1.1, |

1.88 |

2.79 |

1.75, |

4.45 |

2.76 |

2.13, |

3.58 |

|

14 |

1.70 |

1.2, |

2.42 |

2.80 |

1.84, |

4.77 |

2.37 |

1.65, |

3.40 |

|

15 |

1.56 |

1.19, |

2.03 |

3.34 |

2.11, |

5.29 |

2.12 |

1.61, |

2.79 |

|

16 |

1.34 |

1.07, |

1.69 |

2.78 |

1.83, |

4.23 |

1.52 |

1.21, |

1.91 |

|

17 |

1.25 |

0.99, |

1.58 |

1.77 |

1.13, |

2.78 |

1.29 |

1.00, |

1.67 |

|

18 |

1.26 |

1.02, |

1.55 |

1.97 |

1.29, |

3.03 |

1.27 |

1.03, |

1.57 |

|

19 |

1.33 |

1.02, |

1.72 |

1.35 |

0.72, |

2.55 |

1.21 |

0.91, |

1.62 |

|

20 |

0.96 |

0.7, |

1.31 |

1.82 |

1.05, |

3.16 |

1.07 |

0.79, |

1.45 |

|

21+ |

1.00 |

_ _ |

|

1.00 |

_ _ |

|

1.00 |

_ _ |

|

|

Regressions control for Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity (White Non-Hispanic, Black Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Other), Education, Drug Use (Current, Former, Never), Smoking (Current, Former, Never), Marital Status (Never Married, Married, Other), Family History of Alcoholism, Alcohol Dependence (Current, Former, Never). SOURCE: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2001. |

|||||||||

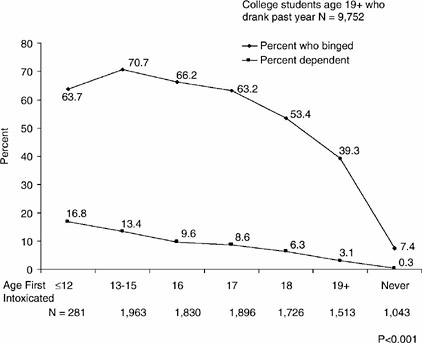

FIGURE 2-1 Ever experienced alcohol related problems according to age started drinking.

SOURCE: Hingson et al. (2000); Hingson et al. (2001); Hingson et al. (2002).

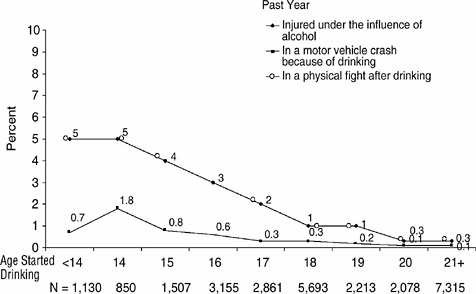

FIGURE 2-2 Past year experiences alcohol related problem according to age started drinking.

SOURCE: Hingson et al. (2000); Hingson et al. (2001); Hingson et al. (2002).

age 44, these findings indicate that risks of injury associated with underage drinking are increased during adolescence, but also persist into adult life (Hingson et al., 2000, 2001, 2002).

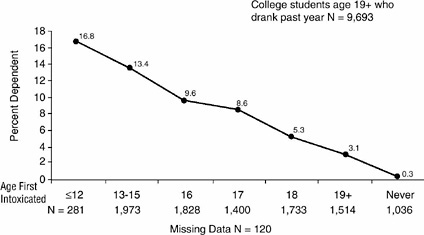

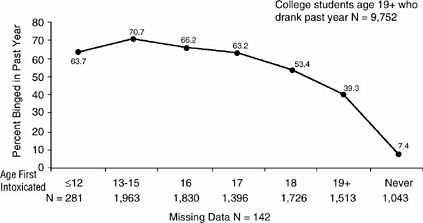

More recent analyses (Hingson et al., 2003a, 2003b) of the 1999 Harvard School of Public Health National College Alcohol Survey of over 14,000 students attending full-time at a representative sample of 4-year colleges (response rate 60 percent), found that the earlier the age at which persons ages 19 and older (N = 9,698) first drank to intoxication, the more likely they were to experience alcohol dependence (Figure 2-3) and frequent binge or heavy drinking—5 or more drinks for a man and 4 or more for a woman on a single occasion (Figure 2-3). The latter relation was seen even after further controlling for alcohol dependence. These relationships were found even after controlling analytically for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, parental drinking history, and age of first smoking cigarettes and marijuana (Figures 2-4 and 2-5). Furthermore, the younger respondents were when first drunk, the more likely they were to report driving after drinking and drinking heavily (5+), riding with a drinking driver, unintentional injuries because of drinking, and unplanned and unprotected sex because of drinking. Moreover, these relations also persisted after con-

FIGURE 2-3 College alcohol study 1999 binge drinking and alcohol dependence among college students who drink according to age first intoxicated.

SOURCE: Hingson et al. (2003a,b).

FIGURE 2-4 Alcohol dependence according to age first drunk: 1999 college alcohol survey.

SOURCE: Hingson et al. (2003a,b).

FIGURE 2-5 Binged past year according to age first drunk: 1999 college alcohol survey.

SOURCE: Hingson et al. (2003a,b).

trolling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, age of first use of cigarettes and marijuana, marital status, and whether a respondent’s parents had an alcohol problem. The increased rates of driving after drinking, driving after 5+ drinks, injuries, and unplanned and unprotected sex after drinking among college students persisted after further controlling for alcohol dependence and frequency of consuming 5 or more drinks on an occasion in the past 30 days (Figures 2-6 and 2-7).

We should caution that most results on age of drinking onset and alcohol-related risks later in life were based on self-report in cross-sectional surveys and, hence, may be subject to limitations associated with self-report. On the one hand, social desirability biases may foster underreporting of alcohol use and injury involvement after drinking. On the other hand, persons willing to report heavy drinking may be less hesitant than others to report injury involvement after drinking. Although the samples studied were nationally representative and large, and in one in particular the response rate was excellent at 90 percent (Grant et al., 1997), it would be useful to replicate these results in a longitudinal study with chemical markers in addition to self-report. Also, it is possible that people who engage in a variety of deviant or illegal behaviors at an early age are more likely to continue them later in life. For example, childhood conduct disorder has been associated with substance abuse later in life (Robins, 1993).

These findings indicate a need for additional research in two areas. First, research is needed to explain why starting to drink at an early age relates to alcohol dependence and to heavier drinking later in life, even among persons who are not dependent. Genetics may play a role by predisposing certain individuals to exhibit tolerance to the physiologic effects of alcohol early in their drinking careers, thereby contributing to the establishment of heavier drinking patterns that persist later in life (Schuckit, 1999). Familial influences, both genetic and environmental, may account for the early onset/later dependence relationship (Prescott and Kendler, 1999). Persons who drink earlier may have physiologic changes that contribute to greater tolerance and the need to drink more to achieve the same pleasurable sensations after drinking. They may have learned to drink in less controlled situations with peers whose drinking norms are to drink to intoxication rather than with family and parents who might drink more moderately. They may also have parents who are heavier drinkers. A central construct of Social Learning Theory (Akers, 1977), Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986), and Problem Behavior Theory (Jessor and Jessor, 1975; Jessor, van Den Bos, Vanderryn, and Costa, 1995) is that adolescents learn and engage in behaviors by observing others. Adolescents whose parents drink alcohol are more likely to drink (Hawkins et al., 1997; Jessor et al., 1995), and adolescents with heavy or problem-drinking parents may be more likely to develop similar patterns.

The Multistage Social Learning Model (Simons, Conger, and Whitbeck, 1988) and Family Interaction Theory (Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, and Cohen, 1990) suggest that parenting styles may also influence the drinking patterns of their children. Generally, parents with authoritarian parenting styles (i.e., demanding), as opposed to authoritative styles (i.e., demanding but also involved and supportive) are more likely to have offspring who develop alcohol problems (Hawkins et al., 1997; Chassin et al., 2002). Parenting styles that lack warmth, support, supervision, and discipline also predict greater adolescent drinking behavior (Reifman, Barnes, Dintcheff, Farrell, and Uhteg, 1998; McGue, Sharma, and Benson, 1996; Gerrard, Gibbons, Zhao et al., 1999; Simons-Morton, Haynie, Crump, Eitel, and Saylor, 2001; Duncan, Tildesley et al., 1995; Cohen, Richardson, and LaBree, 1994; Simons-Morton, Haynie et al., 1999; Simantov, Schoen, and Klein, 2000; Zhang, Welte, and Wieczorek, 1999).

Parental rules about alcohol use by their children, and supervision and enforcement of those rules, may influence how and when youth begin to drink, and how much they drink both as adolescents and adults. In a longitudinal study (Chassin et al., 2002), parents with a history of alcohol dependence and antisocial personality were found to have children who begin binge drinking at younger ages and who binge at least once per week at ages 19 to 20.

Also, persons who develop alcoholism later in life may have had more adverse experiences in childhood such as psychological, physical, and sexual abuse; domestic violence; and substance abuse by parents (DeWit et al., 2000). A recent national household probability survey of 4,023 adolescents ages 12 to 17 (Kilpatrick et al., 2000) reported that adolescents who had been physically assaulted or sexually assaulted, who had witnessed violence, or who had family members with alcohol and drug use problems had at least a twofold increased risk for alcohol and marijuana abuse and dependence. Sexual assault, physical assault, or witnessed violence were also associated with an earlier age of drinking onset (14.4 years compared to 15.1 among those not victimized). The relations between age of onset and subsequent dependence were not specifically examined. Early age drinking and heavy drinking that leads to dependence may be stimulated by efforts to cope or deal with negative family experiences.

Lastly, lax law enforcement of community and state regulations regarding underage drinking may contribute both to starting to drink at a younger age and to the development of heavier drinking patterns that result in dependence.

The second need for additional research is to examine why, even when diagnosis of alcohol dependence and measures of frequency of lifetime and past-year heavy drinking are controlled, persons who began drinking at an earlier age are more likely after drinking to place themselves in situations that pose risk of injury. Several explanations are possible. Those who begin drinking at an early age may be less fearful of injury and situations that pose risk of injury. Some may derive pleasure or a sense of self-esteem by taking risks associated with injury. It is well known that persons who drive after drinking, for example, are more likely to speed and less likely to wear seat belts (Hingson, Howland, Schiavone, and Damiata, 1990). Alternatively, persons who start drinking at earlier ages may not be as aware of or appreciate how alcohol increases injury risk. Studies have shown that people who drive after heavy drinking are more likely to believe they can drive safely after higher amounts of alcohol consumption (Hingson et al., 2003a,b). For example, they may believe the risks of traffic crashes and other injuries increase only for people who are visibly intoxicated. Also, their heavier consumption of alcohol may further impair the judgment of those who start drinking at a younger age. After drinking, they may be less likely than when sober to recognize situations that pose risk of injury or to fully appreciate the risks posed by those situations.

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF UNDERAGE DRINKING

In addition to social and health consequences, there are also economic consequences for underage drinkers and for the rest of society. In this

section, we provide a partial accounting of the immediate and life-course economic consequences of underage drinking. The immediate economic consequences stem from the fact that efforts to prevent and treat underage drinking problems and the consequences of underage drinking divert scarce societal resources from alternative uses. The life-course consequences occur if underage drinkers invest in less human capital, which reduces the standard of living they enjoy over their entire life-course. There are additional life-course consequences to the extent underage drinkers are more likely to suffer drinking problems later in life. A central challenge in this line of research is whether the future labor market and drinking problems would have occurred without the underage drinking. There is a need to isolate the extent to which underage drinking causes these problems and is not merely associated with them.

We want to stress that our partial accounting of the economic consequences of underage drinking does not constitute a complete economic evaluation (cost/benefit analysis or cost-effectiveness analysis). A recent cost of illness study estimates that in 1996, the total cost of underage drinking was $52.8 billion (U.S. Department of Justice, 1999; Levy et al., 1999a). Because reductions in costs are a benefit to society, it is tempting to conclude from this estimate that by eliminating underage drinking, society could reap $52.8 billion of benefits. However, from a practical standpoint, it is not really useful to compare the current situation to a highly unlikely alternative scenario where no one under the age of 21 drinks.

In addition, the cost of illness approach is not consistent with the standard methods of economic evaluation (Cook and Ludwig, 2000; Kenkel, 1994). The cost of illness approach is “implicitly based upon the maximization of society’s present and future production” (Landefeld and Seskin, 1982). In contrast, economic evaluations of underage drinking are based on the value of the increased well-being of members of society, including their enhanced safety and quality of life. Economic evaluations focus on specific interventions and use comprehensive approaches to measure the benefits of a reduction in underage drinking, such as societal willingness to pay in a cost/benefit analysis (Kenkel, 1998) or the number of quality-adjusted life years saved in a cost-effectiveness analysis (Gold, Siegel, Russell, and Weinstein, 1996).

Although not a cost/benefit analysis, the estimates below provide a quantitative perspective on the importance of underage drinking as a public policy problem (Weimer and Vining, 1989). As Mooney and Wiseman (2000) observe about a similar approach to health priority setting, our approach “measures problems and not the value of solutions.” But by providing a more complete understanding of the problem, our estimates are helpful to begin to design appropriate policy solutions.

Immediate Economic Consequences of Underage Drinking: Health Care Expenditures

The immediate consequences of underage drinking are estimated to include at least $8.4 billion of health care expenditures. These expenditures due to underage drinking represent a societal loss because societal resources have been diverted away from other valuable uses. Health care expenditures related to underage drinking include expenditures for alcohol abuse services and expenditures for the medical consequences of alcohol abuse.

We estimate that $7.3 billion are spent annually in the United States for alcohol abuse services for underage drinkers. This estimate is based in part on data from the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. These data indicate that in 1998, 138,000 youths ages 12 to 17 were admitted to substance abuse treatment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002). Of these, 9 percent of youth admissions involved alcohol abuse only, and half involved both alcohol and marijuana. Assuming that half of the treatment expenditures for admissions that involved both alcohol and marijuana were for the treatment of the alcohol abuse, we estimate that an equivalent of 47,000 youth were treated for alcohol abuse. The NLAES provides information on youth over 17, but still underage. These data show that 3 percent of young adults ages 18 to 20 sought treatment for alcohol problems. Based on the current population in that age group, this suggests an additional 356,520 young adults were treated. At an average estimated treatment cost of $18,000 (Goodman, Nishiura, and Humphreys, 1997), this means the United States spent $7.3 billion for alcohol abuse services for slightly over 400,000 underage drinkers in treatment. To develop this estimate, we also assumed but do not know for certain that the average treatment costs for youths and adults are the same. The estimate may be high or low depending on whether average treatment costs for youth are higher or lower than costs for adults.

Expenditures for medical consequences related to alcohol abuse by underage drinkers are estimated based on medical expenditures related to traffic crashes that involved an underage drinking driver. Levy et al., (1999a) estimated that these medical care costs total about $1.1 billion. This estimate omits costs related to medical consequences of underage drinking other than traffic crashes.

Life-Course Consequences

Many underage drinkers are in high school or college; in economic terms they are investing in their human capital. If underage drinkers invest in less human capital than their nondrinking peers, later in life they may be less productive workers who earn less and suffer a lower standard of living.

Although these losses are mainly borne by the underage drinkers themselves, the rest of society shares some of the losses to the extent that over their lifetimes, less productive workers receive more antipoverty transfer payments, pay less in taxes, and generate less economic surplus.

Econometric studies provide fairly consistent evidence that underage drinking problems result in less investment in schooling and other aspects of human capital. Mullahy and Sindelar (1989) analyzed Wave I (1980-1981) of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) data set. The rich ECA data allowed Mullahy and Sindelar to control statistically for a variety of factors related to educational attainment, including family background measures such as father’s education and occupation, and whether the youth suffered from other mental disorders as a teenager. After controlling for these factors, Mullahy and Sindelar estimated that males who experience symptoms of alcoholism before the age of 18 attain on average 1.5 fewer years of schooling. Early symptoms of alcoholism were also associated with a lower probability of later employment in a white-collar professional occupation. Yamada, Kendix, and Yamada (1996) analyzed data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth-1979 (NLSY79). This study was also able to control statistically for a range of other determinants of educational attainment, including family background and the student’s academic aptitude test score. Yamada and colleagues (1996) estimated that youth who were frequent drinkers have a high school graduation rate that is 4.3 percentage points below that of their peers.

Several studies have extended this line of research to estimate the causal impact of drinking on college attainment. Cook and Moore (1993) used the NLSY79 data to investigate the relationship between heavy drinking in high school and the number of years of college eventually completed. A major concern of this study is that observed patterns of drinking and schooling reflect intertwined decisions, making it difficult to know the extent to which drinking causes the reduced educational attainment. To address this concern, Cook and Moore (1993) relied on the natural or quasi-experiments created by differences in states’ alcohol control policies. They estimated that controlling for other factors, students who spend their high school years in states with relatively high beer taxes and minimum legal drinking ages are more likely to graduate college. Using data from the 1993 College Alcohol Study, Wolaver (2002) estimated that high school drinking has small residual effects on college study hours, grade point average (GPA), and declaration of college major; she estimated that drinking while in college has much stronger effects on college outcomes. By combining the results of her study with estimates from labor economics on the returns to college GPA and major, Wolaver estimated that high school and college drinking will eventually translate into substantial earnings losses later in life. For example, she estimated that because of the effects of college drink-

ing on choice of major, college-educated males’ future annual earnings are reduced by 1.6 percent to 3.7 percent, while college-educated females’ future annual earnings are reduced by 2 percent to 9.8 percent.

The econometric estimates we have reviewed suggest that even those underage drinkers who do not experience alcohol problems as adults may experience reduced earnings and a lower standard of living over their life-course because of their high school and college drinking. Other evidence suggests that the earnings losses may be even larger for those underage drinkers who continue to abuse alcohol as adults. A long line of economics research examines the extent to which current alcohol problems reduce the earnings of working adults (for example, Rice et al., 1990; Mullahy and Sindelar, 1989; 1993, 1994; Kenkel and Ribar, 1994; and National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIDA/NIAAA], 1998). Although the evidence is somewhat inconsistent, prime-age males with drinking problems appear to earn less, but so do abstainers, compared to their moderate drinking peers (Cook and Moore, 2000). The positive association between moderate drinking and earnings could reflect a causal impact, where moderate drinking improves health and worker productivity. However, ongoing research is also exploring other possible explanations for the association. The studies that find a positive impact of moderate drinking have not examined underage drinking, and it seems highly unlikely that underage drinking that persists as problematic adult drinking will have beneficial productivity effects.

Most of the studies of adult problem drinking and earnings control for other differences between problem and nonproblem drinkers to focus on the direct impact of alcohol problems on earnings. As Mullahy and Sindelar emphasize, this approach underestimates the total impact of alcohol problems if the alcohol problems are the root causes of some of the other differences. Accounting for the indirect effects of problem drinking through lower schooling attainment and occupational choices substantially increases estimates of the earnings losses associated with problem drinking (Mullahy and Sindelar, 1989, 1993, 1994; Kenkel and Ribar, 1994).

In addition, early drinking together with an adult drinking problem may have an interactive or synergistic effect on earnings. NIDA/NIAAA (1998) reported the results of the econometric analysis of the NLAES data used to estimate the productivity effects of alcohol abuse. The results indicated that early initiation of drinking plays an important role in determining worker productivity later in life. Males who met criteria for alcohol dependence and who also initiated drinking before the age of 15 on average earned 13.1 percent less than their nondependent counterparts. Males who met criteria for alcohol dependence, but who were not early initiators on average, earned only 4.4 percent less. If alcohol-dependent males who initiated drinking while underage experienced the same earn-

ings losses as alcohol-dependent males who initiated drinking later in life, the NIDA/NIAAA productivity costs of alcohol abuse would fall from $84 billion to $51 billion. The difference of $33 billion is an estimate of the portion of the productivity costs currently suffered by alcohol-dependent males that is associated with their previous underage drinking. Of course, association does not prove causation: It is a challenging research question to determine the extent to which the future productivity losses are indeed due to the earlier underage drinking.

Yet another channel for underage drinking to have adverse economic consequences over the life-course is if early drinking is a contributory causal factor in adult drinking problems. As described earlier, in the NLAES data earlier age of drinking is associated with higher rates of subsequent problem drinking and alcohol related unintentional injuries. Cook and Moore (2001) reported new econometric evidence that suggests early drinking is causally related to later drinking. They again relied on the natural or quasiexperiments created by state alcohol control policies to study the persistence of youthful drinking. They found that respondents to the NLSY79 who at age 14 lived in a state where the legal drinking age was 18 instead of 21 were more likely to binge drink years later as adults. This evidence that underage drinking increased the risks of adult drinking problems means that some of the earnings losses experienced by adult problem drinkers actually can be traced back to their underage drinking.

DISCUSSION

No matter how careful the assumptions used in this chapter were to estimate the magnitude of injury mortality associated with underage drinking, it would be preferable if all persons who die from unintentional and intentional injury deaths were tested for alcohol. That would provide a more accurate assessment of the magnitude of alcohol related injury deaths among youth and would, if continued over time, permit more informative analyses of the impact of program and policy changes to reduce underage drinking-related deaths. Part of the reason progress has been made in reducing alcohol related traffic deaths in the past two decades is that most drivers who die in traffic crashes are tested for alcohol. This allows comparison of states before and after new drunk driving and other alcohol regulations with states that do not make those changes to assess whether the regulations produce reductions in fatal crashes involving alcohol. Testing is needed not only for traffic deaths, but for deaths from other unintentional injuries (e.g., falls, drownings, burns, overdoses) as well as intentional injuries such as homicide and suicide.

Also, while research needs to be done to determine whether delaying the onset of drinking will prevent alcohol related problems and economic

consequences later in life, we believe findings outlined in this volume provide important information for physicians and other health care providers to share with their adolescent patients about risks associated with early age of drinking onset. They should explore the age their patients started to drink and advise their patients that people who start drinking at early ages not only have an increased risk of developing alcohol dependence, but they also have an increased risk of experiencing motor vehicle and other unintentional injuries and alcohol related violence, which are the major causes of death among adolescents and young adults. They should point out that decisions about underage drinking and schooling may have lifetime economic consequences as well as sometimes literally being a matter of life and death.

Treatment interventions to reduce drinking have been found to reduce alcohol related traffic injuries, violence, and other harms associated with alcohol abuse. A systematic review of randomized control trials to reduce alcohol dependence and abuse (Dinh-Zarr, Diguiseppi, Heitman, and Roberts, 1986) reported reductions in alcohol related traffic crashes, aggressive behavior (Potamainos, North, Meade, Townsend, and Peters, 1986), assaults (Sitharthan, Kavanaugh, and Sayer, 1996) and domestic violence (Barber and Crisp, 1995), and criminal and domestic violence (Toteva and Mi’anov, 1996) associated with posttreatment reductions in drinking. A more recent randomized trial evaluated a brief motivational intervention to reduce drinking among injured problem drinkers (Gentilello, Rivara, Donovan et al., 1999). One year later, the intervention group averaged 3 drinks less per day and experienced a 47 percent reduction in emergency department, trauma center, and hospital injury admissions. The greatest declines involved intentional injuries and were among mild to moderate drinkers. Similar benefits have been observed in a separate experimental evaluation of adolescents positive for being treated in an emergency department (Monti et al., 1999). A brief motivational intervention for older adolescents (mean age 18) produced a significantly lower incidence at 6-month follow-up of alcohol related injuries and alcohol related problems with dates, friends, police, and parents and at school and a lower incidence of driving while intoxicated than experienced by those who received standard care. Both intervention and comparison groups experienced significant posttreatment declines in drinking.

Furthermore, results on age or drinking onset reinforce the need for policies that reduce adolescent drinking, such as the minimum legal drinking age of 21. That law has been found to reduce drinking, alcohol related traffic deaths, and deaths from unintentional injuries under the age of 21 (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1987; Jones et al., 1992; Shultz et al., 2001; Wagenaar and Toomey, 2002). Some studies (Davis and Reynolds, 1990; Parker, 1995), but not all (Hughes and Dodder, 1992; Engs and

Hanson, 1986), have also found that raising the minimum legal drinking age is associated with declines in fighting among the age groups targeted by the law, and one study reported that increases in the legal drinking age was associated with reductions in sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents (Harrison and Kasslet, 2000). One multistate study found that person who were raised in states with a drinking age of 21 relative to younger ages were not only less likely to drink when they were under age 21, but they were less likely to drink when ages 21 to 25 (O’Malley and Wagenaar, 1991). Community-based programs that use compliance check surveys to assess the extent of sales of alcohol to minors and that increase enforcement to prevent sales to underage persons can reduce underage drinking (Wagenaar, Murray, Gehan et al., 2000) and alcohol related traffic crashes and assault injuries (Holder, Gruenwald, Ponick et al., 2000). Whether these community-based programs to heighten enforcement of laws to prevent underage drinking also reduce other health, social, and economic consequences associated with underage drinking during both adolescence and adult years warrants immediate investigation.

REFERENCES

Akers, R.L. (1977). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: Author.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barber, J.G., and Crisp, B.R. (1995). The pressure to change approach to working with the partners of heavy drinkers. Addiction, 90, 269-276.

Barnes, G.M., Welte, J.W., and Dintcheff, B. (1992). Alcohol misuse among college students and other young adults: Findings from a general population study in New York State. International Journal of the Addictions, 27, 917-934.

Blomberg, R. (1992). Lower BAC limits for youth: Evaluation of the Maryland .02 laws. DOT HS 807 859 Technical Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Brook, J.S., Brook, D.W., Gordon, A.S., Whiteman, M., and Cohen, P. (1990). The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 116, 111-267.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). STD surveillance 1998. Atlanta: Georgia Department of Health and Human Services, Division of STD Prevention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2001). Division of HIV/AIDS prevention surveillance report. Atlanta: National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention

Chassin, L., Pitts, S., and Prost, J. (2002). Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 67-78.

Chou, S.P., and Pickering, R.P. (1992). Early onset of drinking as a risk factor for lifetime related problems. British Journal of Addictions, 87, 1199-1204.

Cohen, D.A., Richardson, J., and LaBree, L. (1994). Parenting behaviors and the onset of smoking and alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 94, 368-375.

Cook, P.J., and Ludwig, J. (2000). Gun violence: The real costs. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cook, P.J., and Moore, M.J. (1993). Drinking and schooling. Journal of Health Economics, 12(4), 411-430.

Cook, P.J., and Moore, M.J. (2000). Alcohol. In A.J. Culyer and J.P. Newhouse (Eds.), Handbook of health economics (pp. 1629-1674). New York: Elsevier Science.

Cook, P.J., and Moore, M.J. (2001). Environment and persistence in youthful drinking patterns. In J. Gruber (Ed.), Risky behavior among youths (pp. 378-438). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Davis, J.E., and Reynolds, N.C. (1990). Alcohol use among college students: responses to raising the purchase age. Journal of American College Health, 38, 263-269.

DeWit, D.J., Adlaf, E.M., Offord, D.R., and Ogborne, A.C. (2000). Age of first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 745-750.

Dinh-Zarr, T., Diguiseppi, C., Heitman, E., and Roberts, I. (1986). Preventing injuries through interventions for problem drinking: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 34, 797-799.

Duncan, T. E., Tildesley, E., Duncan, S. C., and Hops, H. (1995). The consistency of family and peer influences on the development of substance use in adolescence. Addiction, 90, 1647-1660.

Engs, R.C., and Hanson, D.J. (1986). Age specific alcohol prohibition and college students’ drinking problems: Examining the effects of raising the purchase age. Psychological Reports, 59, 979-984.

Gentilello L.M., Rivara, F.P., Donovan, D.M., Jurkovich, J.G., Daranciang, E., Dunn, C. et al. (1999). Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Annuals of Surgery, 230, 473-484.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F.X., Zhao, L., Russell, D.W., and Reis-Bergan M. (1999). The effect of peers’ alcohol consumption on parental influence: A cognitive mediational model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol (Supplement 13), 32-44.

Gold, M.R., Siegel, J.E., Russel, L.B., and Weinstein, M.C. (Eds.). (1996). Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine: Report of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press

Grant, B. (1998). The impact of family history of alcoholism on the relationship between the age of onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22, 144-147.

Grant, B.F., and Dawson, D.F. (1997). Age of onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse, 9, 103-110.

Gruber, E., DiClemente, R.J., Anderson, M.M., and Lodico, M. (1996). Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine, 25, 293-300.

Grunbaum, J., Kann, L., Kindun, S., Williams, B., Ross, J. Lowry, R., and Koelbe, L. (2002). Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States 2001. Morbidity, Mortality Weekly Report, 51(5504), 1-64.

Harrison, P., and Kasslet, W.J. (2000). Alcohol policy and sexually transmitted disease rates. United States, 1981-1995. Morbidity, Mortality Weekly Report, 49, 346-349.

Hawkins, J.D., Graham, J.W., Maguin, E., Abbott, R., Hill, K.G., and Catalano, R.F. (1997). Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58, 280-290.

Henshaw, S.K. (1998). Unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1982-1993. Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 24-29.

Hingson, R., Howland, J., Schiavone, T., and Damiata, M. (1990a). The Massachusetts Saving Lives Program: Six cities shift the focus from drunk driving to speeding, reckless driving and failure to wear safety belts. Journal of Traffic Medicine, 3, 123-132.

Hingson, R., Strunin, L., Berlin, B.M., and Heeren, T. (1990b). Beliefs about AIDS, use of alcohol and drugs and unprotected sex among Massachusetts adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 80, 295-299.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., and Winter, M. (1994). Lower legal blood alcohol limits for young drivers. Public Health Reports, 109, 738-744.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., Jamanka, A., and Howland, J. (2000). Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 1527-1531.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., and Zakocs, R. (2001). Age of drinking onset and involvement in physical fights. Pediatrics, 108(4), 872-877.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., Levenson, S., Jamanka, A., and Voas, R. (2002). Age of drinking onset, driving after drinking and involvement in alcohol related motor vehicle crashes. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 34, 85-92.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., Zakocs, R., Winter, M., and Wechsler, H. (2003a). Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(1), 23-31.

Hingson, R., Heeren, T., Winter, M., and Wechsler, H. (2003b). Early age of first drunkenness as a factor in college students’ unplanned and unprotected sex attributable to drinking. Pediatrics, 111(1), 34-41.

Holder, H.D., Gruenewald, P.J., Ponicki, W.R., Treno, A.J., Grube, J.W., Saltz, R.F., Voas, R.B., Reynolds, R., Davis, J., Sanchez, L., Gaumont, G., and Roeper, P. (2000). Effect of community-based interventions on high-risk drinking and alcohol-related injuries. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(18), 2341–2347.

Hughes, S.P., and Dodder, R.A. (1992). Changing the legal minimum drinking age: Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 568-575.

Jackson, K., Sher, K., Cooper, L., and Wood P. (2002). Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use: Onset persistence and trajectories of use across two samples. Addiction, 97, 517-531.

Jessor, R., and Jessor, S.L. (1975). Adolescent development and the onset of drinking. A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 36, 27-51.

Jessor, R., van Den Bos, J., Vanderryn, J., and Costa, F. (1995). Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology, 31, 923-933.

Jones, N., Pieper, C., and Robertson, L. (1992). The effect of the legal drinking age on fatal injuries of adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 112-114.

Kandel, D., and Yamaguchi, K. (1993). From beer to crack: Developmental patterns in drug involvement. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 851-855.

Kandel, D., Yamaguchi, K., and Chen, K. (1992). Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 153, 447-457.

Kenkel, D.S. (1994). The cost of illness approach. In G.S. Tolley, D. S. Kenkel, and R. Fabian (Eds.), Valuing health for policy: An economic approach (pp. 42-71). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kenkel, D.S. (1998). A guide to cost-benefit analysis of drunk-driving policies. Journal of Drug Issues, 28(3), 795-812.

Kenkel, D.S., and Ribar, D.C., (1994). Alcohol consumption and young adults’ socioeconomic status, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity-Micro, 119-161.

Kenkel, D.S., and Wang, P. (1999). Are alcoholics in bad jobs? In F.J. Chaloupka, M. Grossman, W.K. Bickel, and H. Saffer (Eds.), The economic analysis of substance use and abuse: An integration of economic and behavioral economic research (pp. 251-278). Prepared for the National Bureau of Economic Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kilpatrick, D., Acrerino, R., Saunders, B., Renick, H., Best, C., and Schnury, P. (2000). Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 19-30.

Landefeld, J.S., and Seskin, E.P. (1982). The economic value of life: Linking theory to practice. American Journal of Public Health, 76(6), 555-566.

Leigh, B.C., and Stall, R. (1993). Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist, 48, 1035-1045.

Levy, D., Miller, T., and Lox, K. (1999a). Costs of underage drinking. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Levy, D., Miller, T., Spicer, R., and Cox, K. (1999b, July). Underage drinking: Immediate consequences and their costs. Working Paper, July 1999. Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Bethesda, Maryland.

McGue, M., Sharma, A., and Benson, P. (1996). Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 57, 8-18.

Monti, P.M., Spirit, A., Myers, M., Colby, S.M., Barnett, N.P., Rohsenow, D.J., Woolard, R., and Lewander, W. (1999). Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 989-994.

Mooney, G., and Wiseman, V. (2000). Burden of disease and priority setting. Journal of Health Economics, 9(5), 369-372.

Morral, A., McCaffrey, D., and Paddock, S. (2002). Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect. Addiction, 97, 1493-1504.

Mullahy, J., and Sindelar, J., (1989). Life-cycle effects of alcoholism on education, earnings, and occupation. Economic Inquiry, 26(2), 272-282.

Mullahy, J., and Sindelar, J. (1993). Alcoholism, work, and income. Journal of Labor Economics, 11(3), 494-520.

Mullahy, J., and Sindelar, J. (1994). Alcoholism and income: The role of indirect effects. Milbank Quarterly, 72(2), 359-375.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2000). National Survey of Drinking and Driving Attitudes and Behavior 1999. DOT HS 809190. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2001). Fatality analysis reporting system. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2002). Traffic Safety Facts 2001 Overview. DOT HS 809476. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

National Institute of Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1998). The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States—1992. Bethesda, MD: Author.

O’Malley, P., and Wagenaar, A. (1991). Effects of minimum drinking age laws on alcohol use, related behavior and traffic crash involvement among American youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 52, 478-491.

Parker, R.N. (1995). Alcohol and homicide—A deadly combination of two American traditions. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Potamainos, G., North, W.R.S., Meade, T.W., Townsend, J., and Peters, T.J. (1986). Randomized trial of community-based center versus conventional hospital management in treatment of alcoholism. Lancet, 2, 797-799.

Prescott, C.A., and Kendler, K.S. (1999). Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: A non-causal association. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(1), 101-107.

Reifman, A., Barnes, G.M., Dintcheff, B.A., Farrell, M.P., and Uhteg, L. (1998). Parental and peer influences on the onset of heavier drinking among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 59, 311-317.

Rice, D.P., Kelman, S., Miller, S.L., and Dummeyer, S. (1990). The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse and mental illness. Washington, DC: Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration.

Robins, L.N. (1993). Childhood conduct problems, adult psychopathology and crime. In S. Hodgins (Ed.), Mental disorder and crime (pp. 173-193). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Samson, H.H., Maxwell, C.D., and Doyle, T.F. (1989). The relation of initial alcohol experience to current alcohol consumption in a college population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50, 254-260.