6

Alcohol Use and Misuse: Prevention Strategies with Minors

William Hansen and Linda Dusenbury

Research since 1980 demonstrates the potential for a variety of education and community interventions that target individuals or groups of individuals to reduce the onset of alcohol use and misuse among minors. This chapter reviews approaches that involve schools, families, and communities and recommends strategies for achieving a broad-based effort for reducing alcohol use among youth.

SCHOOL-BASED APPROACHES

Extensive research has been completed during the past two decades on school-based approaches to alcohol prevention. To a large extent, these approaches have taken advantage of several facts. Programmatically, students in schools are relatively easy to reach; it is the setting in which most youth can easily be found, there is a place in the curriculum of most schools for alcohol to be addressed, and addressing alcohol use and misuse is consistent with the broader goals of education.

In many instances, research projects have not limited the focus of intervention to alcohol. Many projects—even those specifically designed to prevent alcohol use and misuse—have included other substances as well. In part, this approach reflects researchers’ understanding of the relationships among substances; alcohol is often used early in the cycle of substance use. Those who drink heavily are more likely to go on to use other substances. Those who use other substances are also more likely to begin drinking heavily and develop problematic patterns of use.

Three prevention projects that have had an alcohol-specific focus have been completed. These include: (1) the Alcohol Misuse Prevention Trial (AMPS) (Dielman, Shope, Leech, and Butchart, 1989); (2) the Adolescent Alcohol Prevention Trial (AAPT) (Hansen and Graham, 1991); and (3) Project Northland (Perry et al., 1996 [main outcome paper Phase I]; Perry et al., 2002 [main outcome paper Phase II]).

AMPS

The AMPS program was designed to prevent the misuse of alcohol among students enrolled in their last year of elementary school (Dielman, Shope, Butchart, and Campanelli, 1986; Dielman et al., 1989). The original goal of AMPS was to reduce the prevalence of alcohol use among middle school students through an intervention that focused on resistance skills training. Students were taught skills believed to be necessary to avoid alcohol misuse, including saying “no” to peer pressure. Fifth- and sixth-grade classes of students were randomly assigned either to receive the program or to serve as no-treatment controls. Fifth-grade classes were also randomly assigned to receive or not to receive a booster program. Half of all students in each group were tested prior to the beginning of the program. All students were tested 2, 14, and 26 months after program delivery.

There was no reduction in alcohol misuse among fifth graders who received the AMPS program compared with those in the control group. This was true for those enrolled in the core AMPS program as well as those who received the booster program.

For sixth graders, there were some reductions in alcohol misuse. There was a lower rate of onset of drinking among all students that was, statistically speaking, marginally significant. Effects were stronger when only students with some prior experience with alcohol were considered. Notably, increases in drinking by sixth-grade students who had some prior experience with drinking were significantly lower among those who received the program compared to those who did not. There were no differences between groups if students hadn’t used alcohol prior to the start of the study.

Because this evaluation of AMPS found that effects were not maintained over time, an enhanced AMPS curriculum was developed, which included more sessions, role playing, and norm-setting activities within the program. The goals of the enhanced AMPS program were to teach students about alcohol use and misuse in their social contexts and to develop students’ skills for identifying and resisting social pressures to use alcohol. The purpose of this research was to describe the development, implementation, and evaluation of this enhanced AMPS curriculum. Specifically, students’ exposure to AMPS and their prior drinking experiences were studied in

relation to their curriculum knowledge and rates of alcohol use and misuse over time.

A total of 1,725 students from 35 elementary and middle schools in southeastern Michigan participated in the study. Schools were randomly assigned to treatment and control conditions. The treatment condition received the AMPS curriculum and the controls did not. The AMPS curriculum was administered to the treatment students in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. Questionnaires were administered to both treatment and control students at the beginning of the study in the sixth-grade fall semester and again during the spring semesters of sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. The students were surveyed about their alcohol use and misuse, curriculum knowledge (alcohol facts, knowledge of pressures to use alcohol, norms regarding use, decision-making skills, and resistance skills), and prior drinking history. Based on students’ prior alcohol use, they were assigned to one of three groups: (1) abstainer; (2) supervised drinker, and (3) unsupervised drinker.

Treatment group students had significantly higher levels of curriculum knowledge compared to control students. Across all three posttests from grades six through eight, the treatment group’s mean knowledge scores increased significantly from pretest. Control students’ mean knowledge scores did not increase significantly over time from pretest to grades seven and eight posttests.

Increases in the rates of alcohol use were similar for treatment and control group abstainers and supervised drinkers. Unsupervised drinkers in the control group increased their alcohol use more than did similar students in the treatment group. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

The rate of alcohol misuse over time for prior abstainers and supervised drinkers appeared to be about the same for both treatment and control conditions. For abstainers, both the treatment and control groups significantly increased their alcohol misuse from pretest to all posttests. Control supervised drinkers significantly increased their alcohol misuse from pretest to posttests at grades seven and eight. Treatment group supervised drinkers significantly increased their alcohol misuse from pretest to grade eight posttest. However, the rates of misuse over time for prior unsupervised drinkers were different compared to the supervised drinkers and abstainers. The control unsupervised subgroup significantly increased their misuse rates from pretest to grade eight posttest; the treatment unsupervised group did not significantly increase their misuse rates over the same time period.

The results of this evaluation imply that programs like AMPS may be most effective among students with prior histories of unsupervised drinking. Students who had a history of unsupervised drinking and received the

intervention increased their rate of alcohol use and misuse less over time compared to unsupervised drinkers in the control condition. The authors (Dielman, Shope, Butchart, and Campanelli, 1986; Dielman, Shope, Leech, and Butchart, 1989) suggested that the success among students with a prior unsupervised drinking history may be because they had more reason to find the program material relevant. Programs that utilize the social influence approach, such as AMPS, may benefit form identifying students based on their prior drinking histories. This could help tailor programs for students from different drinking backgrounds. Although students who have histories of unsupervised drinking clearly have the most to gain from a prevention program, students with less experience or no experience with drinking should be targeted as well. Taking into account students’ drinking histories may enhance the effectiveness of alcohol use prevention programs.

A recently completed analysis of data from AMPS examined the role of resistance skills and normative beliefs (Wynn, Schulenberg, Maggs, and Zucker, 2000). Results indicate that normative beliefs mediated the effect of the intervention on alcohol overindulgence from 7th through 8th grade and from 8th through 10th grade. In contrast, although the prevention program increased refusal skills, the ability to resist peer pressure did not mediate the effect of the program.

AAPT

The goal of AAPT (Donaldson, Graham, and Hansen, 1994; Hansen and Graham, 1991) was to test the importance of normative education versus building skills for resisting peer pressure as program components for preventing alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. AAPT was an efficacy trial with a high degree of control over the delivery of program content by trained specialists who were employees of the University of Southern California.

Two intervention strategies were developed. The first approach was titled Normative Education. The goal of this program was to establish beliefs in conventional norms among students. This program taught students that the prevalence of substance use among their peers was lower than they might otherwise expect. It also taught students that substance use was generally not approved of by their peer group. The norm-setting activities currently included in All Stars (Hansen, 1996) had their origins in this research project and, except for improvements that have been incorporated over the years, are essentially the same sets of lessons that were developed for AAPT.

The second approach was titled Resistance Skills Training. The goal of this program was to help students to build skills to resist peer and other forms of social pressure. Students were taught a variety of techniques for identifying and resisting social pressure. They were taught skills for being

assertive in peer interactions and they practiced these skills through role-played scenarios. Individual approaches were compared, as was a program that included both elements and a program that included neither element. The latter included only information about consequences of using alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana.

The Normative Education program produced lower rates of increase for all three substances measured. The Resistance Skills Training program, in contrast, did not produce lower use rates for any of the substances. Between pretest and posttest, classes that were exposed to either the Information Only program or the Resistance Skills Training Only program demonstrated increases in the percentage of students reporting “ever being drunk” (11 percent). The increase for students in classes exposed to Normative Education was 4 percent. Only 1.4 percent of students reported having problems that could be associated with alcohol use in the seventh grade. By eighth grade, problems associated with alcohol among students who were not enrolled in a Normative Education class increased 2.4 percent. Problem alcohol use among students in Normative Education classes increased 0.3 percent.

Initial use of alcohol among students in Normative Education classes increased 11 percent. Among students in classes that did not receive Normative Education, the increase was 14 percent. At pretest, 5 percent of students overall reported drinking during the past week. This increased by 5 percent among those with no Normative Education classes, but increased less than 3 percent among students exposed to Normative Education. Furthermore, the onset of marijuana use was lower among students exposed to the Normative Education program. Reports of ever having used marijuana increased 2.2 percent among students exposed to Normative Education; the rate increased 6.2 percent among students who did not receive Normative Education. Normative Education students reported lower smoking in the past 30 days (4.8 percent) than students not enrolled in Normative Education (6.5 percent).

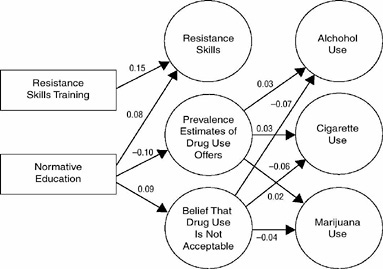

The outcomes of the AAPT interventions (see Figure 6-1) were examined by looking at the role specific mediators played in changing substance use onset (Donaldson et al., 1994). Findings indicated that both programs changed their primary targeted mediating variables. The Resistance Skills Training program significantly improved the skills of students who received instruction. Similarly, students exposed to Normative Education had improved significantly, meaning more conventional perceptions of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use norms within the peer group. Of significant interest was the finding that the presence of offers to use drugs was actually reduced among those who participated in the Normative Education program.

The analysis of these data revealed no relationship between improving

FIGURE 6-1 Statistically significant paths: AAPT examination of mediating variables.

SOURCE: Donaldson et al. (1994).

resistance skills and reducing drug use. In contrast, improved normative beliefs and reduced offers for drug use were significantly predictive of a reduction in the onset of drug use. A recent study (Taylor, Graham, Cumsille, and Hansen, 2001) in which growth curve modeling was applied to AAPT data over a 5-year period (through grade 11) demonstrated that the Normative Education program had two enduring effects. The first effect was to suppress the overall level of alcohol and tobacco use throughout the period. The second effect was to suppress the rate of increase of these substances. Both results speak strongly to the efficacy of the applied normsetting approach to achieving prevention goals.

AAPT intervention approaches have been integrated into All Stars, a program that targets alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and inhalant use as well as fighting. Short-term results show a similar pattern with significant reductions in alcohol and tobacco use. An analysis of the program’s effects on mediators reveals that the program was effective only when targeted mediators were successfully manipulated by instructors.

Project Northland

Project Northland is a communitywide alcohol use prevention program for young adolescents that builds on research of the past two decades in

primary prevention of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use with young adolescents. Project Northland extends its approach to prevention by systematically linking and studying curricula in schools, parental involvement programs, extracurricular peer leadership, and communitywide task forces for young adolescents in grades 6 to 8 and in grades 11 and 12 (Perry et al., 2002). This is the only project targeting high school students. Project Northland involved 24 school districts and 28 adjoining communities in northeastern Minnesota. Although Project Northland is thus more than a classroom curriculum, it includes a school-based intervention.

Project Northland included three school interventions—Slick Tracy, delivered during sixth grade; Amazing Alternatives!, delivered during seventh grade; and PowerLines, delivered during eighth grade. The objectives of the program were to: (1) create a nondrinking norm for teens; (2) provide peer and parent role models; (3) structure alcohol-free opportunities and decrease opportunities for teens to get alcohol; (4) provide knowledge of social influences and increase self-efficacy to resist influences; and (5) reinforce the value of nondrinking.

The Slick Tracy Home Team Program was implemented with sixth-grade students and their parents, and involved a “home team” approach, consisting of four sessions of activity story books (with characters Slick Tracy and Breathtest Mahoney as role models). Students completed activity books with their parents as homework during four consecutive weeks. In addition, Northland Notes for Parents were included in each Slick Tracy activity book and contained information for parents on young adolescent alcohol use. The intervention also involved small group discussions around the themes of the books during school and the Slick Tracy Family Fun Night, an evening fair where students’ posters and projects from the program were displayed. The major themes of the Slick Tracy Home Team Program included facts and myths about alcohol use, advertising influences, peer influences, and parent-child communication (Williams, Perry, Dudovitz, and Veblen-Mortenson, 1995).

The Amazing Alternatives! Program consisted of a peer-led classroom curriculum. The overall theme was to introduce seventh-grade students and their parents to ways to resist and counteract influences on teens to use alcohol, and to introduce alternatives to drinking. The classroom program included eight sessions of peer- and teacher-led activities over 8 weeks (Hingson, Howland, Schiavone, and Damiata, 1990; Perry, et al., 1989). The program used audiotape vignettes, group discussions, class games, problem solving, and role plays related to themes of why young people use alcohol and alternatives to use, the influences to drink, strategies for resisting those influences, normative expectations that most people their age do not drink, and intentions not to drink. Peer leaders for the classroom program were selected with an open election in which students chose individu-

als they “liked and respected,” without any admonishments from teachers to restrict the leaders to nonusers of alcohol.

PowerLines was implemented in 1993-94 and consisted of an eight-session classroom curriculum. The goals of the eighth-grade interventions were to introduce students to the “power” groups (individuals and organizations) within their communities that influence adolescent alcohol use and availability and to teach community action/citizen participation skills. Students interviewed parents, local government, law enforcement, school teachers and administrators, and retail alcohol merchants about their beliefs and activities concerning adolescent alcohol use. Students conducted a “town meeting” in which small groups of students represented various community groups and made recommendations for community action for alcohol use prevention.

Alcohol use outcomes were measured by the Alcohol Tendency Scale and its separate items for spring 1994 (see Table 6-1). Among all students, those in the intervention districts had statistically significantly lower scores on the Tendency Scale by the end of eighth grade, indicative of less likelihood of drinking, than did students in the reference districts. The Tendency Scale score was also significantly lower among baseline nonusers (those who had not yet used alcohol at the beginning of sixth grade) in the intervention districts.

For all students, the percent of students who reported alcohol use in the past month and past week was significantly lower in the intervention group at the end of eighth grade. For nonusers of alcohol at the pretest, the percentages of students reporting alcohol use, cigarette use and marijuana use were significantly lower in the intervention districts at the end of the eighth grade. Differences between conditions in multiple-drug use among all students were examined by calculating the prevalence of combinations of alcohol and cigarette use. Among all students, 14.3 percent of those in the intervention districts reported both using alcohol in the past month and smoking cigarettes on more than one or two occasions. This compares with 19.6 percent of those in the reference districts, a difference that was statistically significant and indicates a 27 percent reduction in “gateway” drug

TABLE 6-1 Project Northland: Eighth-Grade Outcomes for All Students (N = 1,901)

|

Outcome |

Intervention Communities |

Reference Communities |

|

Alcohol Tendency Scale (8-48) |

16.0 |

17.5 |

|

Past month alcohol use |

23.6% |

29.2% |

|

Past week alcohol use |

10.5% |

14.8% |

use, or drug use that progresses from nonillicit substances to more dangerous and illicit substances. These outcomes were further analyzed using mediation analysis, which found the changes in peer norms and peer role models targeted in the intervention were the most predictive of change in alcohol use (Komro et al., 2001). By 10th grade, effects had decayed and no differences between groups were observed. However, Project Northland resumed with students in the eleventh and twelfth-grades, and rates of increase in alcohol use were significantly reduced in the intervention districts compared with the reference districts from tenth to twelfth grades (Perry et al., 2002).

The school components of Project Northland were integrated with family and community interventions. This research implies that interventions that focus on norm setting, that are delivered in an interactive manner, and that are integrated with broad-based approaches have significant potential to reduce the onset of alcohol use and misuse among minors.

Lessons Learned from Other School-Based Prevention Projects

A number of researched programs that target multiple substances, primarily including tobacco and marijuana, have also demonstrated reductions in alcohol use. Indeed, many of these projects target multiple substances because of the evidence that demonstrates strong linkages among them.

The Life Skills Training program, a broader personal and social skills training program for middle school students, is designed to prevent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, and has been evaluated in 10 separate published evaluation studies (Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Botvin, and Diaz, 1995; Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Tartu, and Botvin, 1990; Botvin et al., 1989a; Botvin, Dusenbury, Baker, James-Ortiz, and Kerner, 1989b; Botvin et al., 1992; Botvin and Eng, 1982; Botvin, Renick, and Baker, 1983; Botvin, Baker, Botvin, Filazzola, and Millman, 1984; Botvin, Schinke, Epstein, and Diaz, 1994). These studies have shown relative reductions of up to 50 to 75 percent in tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana use at seventh-grade posttest. A recent 6-year follow-up of 4,466 seventh-grade students showed that results erode only slightly by the end of high school, with 66 percent reductions in the use of all three: tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana. Minority students comprised at least 75 percent of the sample in 6 out of 10 separate studies; in each of these 6 studies, there was a combination of Blacks (11 to 87 percent) and Hispanics (10 to 74 percent).

There has been one published, 6-year evaluation of Project Alert (Bell, Ellickson, and Harrison, 1993; Ellickson and Bell, 1990; Ellickson, Bell, and Harrison, 1993), a social resistance skills training program for students in grades six and seven, or seven and eight. Project Alert consists of 11

sessions in the first year, and 3 in the second. Results showed immediate posttest relative reductions in drinking of up to 50 percent. In the second year of the study (in the eighth grade), there were declines in marijuana use of 33 to 60 percent, and smoking reductions of 17 to 55 percent. All positive effects disappeared after 15 months. In addition, there were some negative effects for high-risk youth. Minority students comprised 30 percent of the sample (10 percent Asian, 9 percent Hispanic, 8 percent Black, 3 percent other ethnic groups). Perhaps in response to some of the questions about Project Alert’s lasting impact, the project has been expanded to include an intervention for high schools that is now being tested in South Dakota (RAND, 2000).

A substance abuse prevention component for grades five through eight that was later integrated into the Michigan Model, a comprehensive health education curriculum, was recently evaluated in a small study (Shope, Copeland, Marcoux, and Kamp, 1996). The program significantly reduced the rate of smoking, drinking, marijuana use, and cocaine use, but not smokeless tobacco use. One concern about the generalizability of these findings to the Michigan Model is whether teachers will implement the 7 lessons related to drug use with fidelity when they are being asked to implement 40 to 60 sessions of the comprehensive health education program each year.

Project STAR (Pentz et al., 1989; Pentz et al., 1990) included an 18-session social resistance skills training approach for students in grades five to eight. Drinking, smoking, and marijuana use dropped 30 percent at 1-year follow-up; results persisted through the 3 years of the study. The intervention involved multiple components (school curriculum, family program, media spots), but only the presentation of the school curriculum was experimentally manipulated.

FAMILY-BASED APPROACHES

Research has identified important family predictors of alcohol use. Parents are a powerful source of influence on their children. That influence can be negative or positive. Parental alcohol abuse, for example, has been shown to increase the likelihood that children will drink. Compared with children of social drinkers, adult children of alcoholics are more likely to report that they have drunk more all their lives and more frequently during high school (Ross and Hill, 2001). In terms of positive influence, Catalano (1993) calls parents “a formidable key in preventing teen substance use,” for parents have the power to affect their children’s decisions whether or not to use alcohol (as well as other drugs) in two important ways: they can inhibit their children’s use directly, and they can reinforce their children’s involvement in positive alternatives (such as religious or athletic programs)

that are inconsistent with alcohol and other drug use (Bry and Slechta, 2000).

Parental monitoring also is a key factor in reducing the likelihood that young people will drink (Dusenbury, 2000; Jackson, Henrickson, and Dickinson, 1999). Easy access to alcohol also has been associated with higher rates of drinking among young people (Jackson et al., 1999). Other factors that increase risk include family norms that support drinking by children at home, and the absence of clear family rules and policies prohibiting the use of alcohol (Jackson et al., 1999).

A number of family-based prevention programs have been developed. Most of these are concerned with substance abuse broadly defined (alcohol and other drug use). Some of these programs are universal programs targeting all youth; other selective approaches respond to the needs of youth at high risk for alcohol or other drug abuse because their parents abuse these substances.

Five family-based prevention projects that have had an alcohol-specific focus have been completed. These include: (1) Prenatal and Infancy Home Visitation by Nurses (Olds, 1997); (2) The Michigan State University Multiple Risk Outreach Program (Nye, Zucker, and Fitzgerald, 1995; Maguin, Zucker, and Fitzgerald, 1994); (3) Family Matters (Bauman, Ennett, Foshee, Pemberton, King, and Koch, 2002); (4) Project Northland (Williams, Perry, Farbakhsh, and Veblen-Mortenson, 1999); and (5) Preparing for the Drug-Free Years (Kosterman, Hawkins, Spoth, Haggerty, and Zhu, 1997).

Prenatal and Infancy Home Visitation by Nurses was a program serving low-income women during pregnancy and continuing into early childhood (Olds, 1997). Nurses were used to educate mothers and support them during the important transition to becoming a parent. Nurses addressed maternal health issues, provided education about child development and parenting, encouraged support by family and friends, and provided linkages to needed services. The program focused on three general risk factors: the mother’s use of drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes during pregnancy; maladaptive care of the child; and issues relative to the mother’s adjustment, including family size, work, and welfare dependence.

Results revealed that the program improved diet and reduced smoking during pregnancy, reduced subsequent child neglect and abuse, improved children’s IQ scores, and reduced risk for later substance use by children and parents. A 15-year follow-up revealed 79 percent fewer incidents (verified reports) of child abuse or neglect, 69 percent fewer arrests of the mother, and a 44 percent reduction in behavioral problems due to alcohol and drug abuse.

The Michigan State University Multiple Risk Outreach Program was designed to interrupt important family mediators of later alcoholism. The project recruited fathers from a group of men convicted of driving while

impaired. The program provided parents with training in consistent monitoring and reinforcement for prosocial behavior. Families were assigned to one of three conditions: (1) both parents participate (n = 22); (2) only mothers participate (n = 20); and (3) no-treatment control group (n = 23).

The 10-month intervention focused on child management training and included a component on marital problem solving. The program consisted of weekly sessions and two telephone contacts per week until parents mastered the training objectives (usually 4 months), followed by biweekly sessions and weekly telephone contacts to support and maintain mastery.

The program resulted in significant improvements in child behavior (measured on the Child Behavior Rating Scale-Preschool Version) when families completed the program and when mothers had a high level of participation and investment in the program. Only increases in positive behaviors were sustained at follow-up. The effects were strongest when both parents participated (Maguin et al., 1994; Nye et al., 1995).

Family Matters is a universal, family-based prevention program that targets alcohol and tobacco. The intervention mails parents four booklets, each of which is followed up by a telephone call from a health educator. An evaluation with 1,014 families with 12- to 14-year-old children revealed reductions in tobacco and alcohol use by children in the 12 months following the program. The program also increased rule setting about tobacco and alcohol use in families (Ennett et al., 2001; Bauman, Foshee, Ennett, Pemberton, Hicks, King, and Koch, 2001).

As noted earlier, Project Northland is a multicomponent alcohol prevention program for students in middle school. Specifically, the program includes family-based components in sixth and seventh grades, a school-based component in seventh grade, and a community-based component in eighth grade. During eight sessions per year for 3 years, the school-based program emphasizes Normative Education and Social Resistance Skills Training. During the sixth and seventh grades, highly appealing informational packets and homework activities were completed by parents and children together and were brought by students or mailed to the families. They included suggestions for setting up family policies, holding family meetings, and communicating with teens.

Toomey and colleagues (1996) found in evaluating the seventh-grade mailed program that a third of parents completed activities that had been mailed to them. Mailing materials home to parents provides greater flexibility than having students take materials home from school. As a result of the parent program intervention, students were more likely to be aware of their family’s rules concerning alcohol, and had more discussions about alcohol with their parents. The program also had a positive impact on parent-child communication and other important family protective factors.

Outcome studies over 3 years with 1,901 sixth graders showed that the multicomponent program reduced use of alcohol as well as tobacco and marijuana. The program also reduced students’ misperceptions about the prevalence of drinking. In terms of effects specific to the family-based component, by the end of sixth grade more intervention than reference students reported that their parents had spoken to them about drinking. By the end of eighth grade more students reported that their families had rules about drinking.

Preparing for the Drug-Free Years (PDFY) is a universal, five-session program for parents of children ages 8 to 14. This program, designed primarily for parents, empowers parents with the skills needed to enhance protective factors (e.g., bonding to child by increasing opportunities for involvement with the child as well as interaction; how to effectively resist negative influences and reinforce good behavior through effective management techniques) and reduce risk factors (e.g., family conflict). The program trains parents in communication skills so they can effectively communicate norms that do not support substance use. Parents also learn skills and techniques for effectively managing their families. Finally, the program helps parents teach their children the skills they will need to effectively resist influences to use alcohol.

The program is based on the social development model. In order to make the intervention sensitive to the culture of the target community, community members who have received training deliver the program. The use of videos in each session helps to standardize content.

Kosterman, Hawkins, Spoth, Haggerty, and Zhu (1997) report that PDFY increased communication between parents and children and improved the quality of parent-child relationships in two rural, economically depressed communities in the Midwest. Other studies suggest the program can be adapted to other cultural groups. Park and colleagues (2000) report that the program significantly improved parents’ norms concerning alcohol use, and reduced the growth of alcohol use in their children. Spoth, Guyll, and Day (2002) report a savings of $5.85 in alcohol-use disorder costs for every dollar spent on the program.

COMMUNITY-BASED APPROACHES

Communities play an important role in supporting norms for alcohol use, as well as restricting alcohol availability. Social interaction and social influences are critically important in drinking. To prevent underage drinking, community factors and norms clearly must be addressed (Wagenaar and Perry, 1994).

A variety of prevention efforts have included multiple components involving schools, families, communities, and media (for example, Pentz et al.,

1989; Perry et al., 1996; Hawkins, Catalano, and Miller, 1992). Gorman and Speer (1996) identified eight published evaluation studies of community-based approaches. Many of these were multicomponent interventions. Although experts agree that comprehensive approaches that target multiple domains are much more likely to be effective, evaluations of multicomponent approaches have not yet determined how much each component contributes to a program’s overall effectiveness. Four community-based prevention approaches are described: (1) Project Northland; (2) Day One Community Partnerships; (3) Communities Mobilizing for Change; and (4) Community Trials Intervention to Reduce High Risk Drinking.

In Project Northland, communitywide task forces were mobilized to reduce the availability of alcohol and to improve community attitudes about and against teen drinking (Perry et al., 1996; Williams and Perry, 1998) during the first year of the project. Task forces included members from a cross-section of the community: government, law enforcement, school representatives, business representatives, health professionals, youth workers, parents, concerned citizens, clergy, and adolescents. During the first year, task forces focused primarily on promoting awareness of alcohol issues among teens and the organization and implementation of alcohol-free recreational activities for adolescents (Veblen-Mortenson et al., 1999).

During the second year of the program, the intervention included a peer participation program named T.E.E.N.S. (The Exciting and Entertaining Northland Students). This intervention was designed to provide peer leadership experience outside the classroom through participants’ involvement in planning alcohol-free activities for seventh-grade students. Adult volunteers were recruited from the middle and junior high schools and surrounding communities to facilitate the T.E.E.N.S. groups. One-day leadership training sessions were held for student representatives. The leadership training included learning methods to find out seventh graders’ favorite activities, to plan a budget for an activity, and to publicize an activity. Planning booklets were given to students. Sixteen percent of the students in the program participated in planning at least one activity for their peers and nearly 50 percent attended at least one activity. These student planners significantly reduced their levels of alcohol use by the end of seventh grade (Komro, Perry, Veblen-Mortenson, and Williams, 1994; Komro et al., 1996).

During the second year of the project, communitywide task force activities involved the passage of five alcohol-related ordinances and three resolutions, including enactment of local ordinances requiring responsible beverage service training to prevent illegal alcohol sales to underage youth and intoxicated patrons in three of the communities. Other activities included the initiation of a Gold Card program to link community businesses

and schools. Gold Cards issued to students by participating businesses provided discounts to students who pledged to be alcohol and drug free.

During the third year of the project, T.E.E.N.S. activities continued. The communitywide task forces increased their collaboration with existing organizations to make as many linkages as possible with local groups that directly influence underage drinking. Activities included: (1) discussions with local alcohol merchants about their alcohol-related policies concerning young people; (2) distribution of materials that support policies concerning the sale of alcohol to minors, including ID checks and legal consequences for selling alcohol to minors; (3) ongoing meetings to initiate new Gold Card Programs to link community businesses and schools; and (4) continued sponsorship of alcohol-free activities for young teens, including the establishment of a teen center in one community.

Day One Community Partnerships involved a community coalition in a diverse urban community in southern California. Comprehensive alcohol prevention activities were used. The most promising was the adoption of comprehensive policies by the city government to reduce the availability of alcohol to minors. A 3-year survey indicated a trend in reducing monthly use of alcohol for middle and high school students. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in weekly alcohol use for 12th graders (Rohrbach, Johnson, Mansergh, Fishkin, and Neumann, 1997).

Communities Mobilizing for Change is a Center for Substance Abuse Prevention model program. The program is designed to organize and mobilize communities to reduce access to alcohol for 13- to 20-year-olds. It is a universal prevention intervention that provides resource materials to help communities organize, including materials for civic groups, faith organizations, schools, law enforcement, and liquor licensing boards. Materials include alcohol compliance check procedure manuals, model ordinances, model public policies, institutional policies, and research material. The intervention reduced drinking among 18- to 20-year-olds. It improved practices in places that serve alcohol, it increased the number of alcohol merchants checking age, and reduced the number of older teens providing alcohol to other teens.

Community Trials Intervention to Reduce High Risk Drinking is a multicomponent, community-based intervention that targets environmental factors supporting alcohol use (Holder et al., 1997). The intervention is designed to increase community awareness, reduce access to alcohol for young people, and encourage responsible beverage service and enforcement. Six intervention and control communities in southern California and South Carolina participated in an evaluation. These communities had populations of approximately 100,000. The intervention decreased sales to minors, increased driving under the influence enforcement, and increased coverage of alcohol issues in the media. Results indicated that driving under the

influence was cut in half. Following the intervention, half as many people reported that they drank too much. There was a 10 percent reduction in nighttime crashes, and a 6 percent reduction in crashes where the driver was under the influence of alcohol. Forty-three percent fewer assault injuries were treated in emergency rooms.

KEY ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE ALCOHOL PREVENTION APPROACHES FOR MINORS

From these studies, we conclude that there are several important lessons to be learned about what key elements are important for preventing the use and misuse of alcohol among minors.

Strategies That Work

Interventions should be multicomponent and integrated. Schools provide a captive population for the delivery of prevention programs. School-based programs have shown evidence of effectiveness. Similarly, family-and community-based interventions have produced short-term reductions in the prevalence and intensity of alcohol use. Prevention benefits when all of these venues are used in concert in a coordinated and mutually supporting manner. A meta-analysis by Tobler and colleagues (2000) revealed that systemwide change interventions were most effective. These interventions utilized a community component involving family and other community leaders (e.g., teachers, counselors) or tried to change the school environment. Communities and schools are encouraged to use interactive substance use prevention programs, especially those that combine community involvement or work to change school environment. Communities should adopt prevention interventions that include school, family, and community components.

Interventions should be sufficient in dose and follow-up. Passing through adolescence takes a decade. During this period, significant developmental changes occur. For interventions to be effective, they must be delivered throughout this period to have lasting effects. Educational and family programs focus most heavily on the first part of adolescence and then become increasingly rare. The increased use of boosters and multiyear programs should be encouraged. Community interventions may similarly come and go during the period of a decade. However, a combined and consistently implemented approach to prevention will yield results.

Programs need to establish nonuse norms. Extensive research demonstrates that establishing positive norms is a key to preventing alcohol use and misuse. During adolescence, it is common for youth at risk for engaging in inappropriate alcohol behaviors to grossly overestimate the prevalence and acceptability of alcohol use among peers. One method of chang-

ing norms is to change these prevalence estimates by providing the real data, or to employ peer leaders who model nonuse in their classrooms and communities.

Parental monitoring should be stressed. Research on prevention with families consistently demonstrates that parental monitoring, including monitoring free time and time with friends, is highly effective as a strategy for preventing the onset of alcohol use and misuse. Programs that provide parents with skills for active monitoring should be encouraged. Increasing parent-child communication concerning alcohol use promotes positive norms at home and helps parents to explain reasons for monitoring their children.

Educational programs need to be interactive in their approach. The effective educational programs reviewed earlier were all highly interactive in their nature. That is, they did not rely on didactically presented messages, but used teaching techniques that encouraged participants to be actively engaged in the process of forming social norms. The Tobler et al. (2000) meta-analysis revealed that interactive programs that delivered more hours of programming were more effective than interactive programs that delivered fewer hours. This trend was not evident among noninteractive programs. This was true for all studies together and for the high-quality studies.

Interventions should be implemented with fidelity. There is strong evidence that the quality of program delivery is highly related to successful outcome (Dusenbury, Brannigan, Falco, and Hansen, 2003). Training for providers is crucial. Providers also must have sufficient time to become fluent in delivering the program. On the initial attempt, program providers typically focus on understanding the mechanics of a program. Only after they have mastered the mechanics of program delivery are they able to focus on underlying psychological and sociological constructs that define quality implementation.

Interventions should limit access to alcohol. Family and community interventions that were successful included a focus on limiting youth access to alcohol. Such approaches need to include not only the adoption of laws and ordinances, but their enforcement and the development of a strong social norm that supports the intent of such policies.

Interventions should be institutionalized. Institutionalization is crucial for prevention to realize its full potential. Institutionalized programs can have long-lasting effects.

Strategies That Do Not Work

Noting which strategies do not work is important because these should be avoided. Many programs have not yet been demonstrated to be effective.

However, lack of evidence of effectiveness is different than evidence about contraindicated approaches. Those that researchers have broadly concluded either not to work or to be counterproductive include: (1) scare tactics; (2) congregating high-risk students; (3) exclusive focus on information; and (4) a failure to specifically focus on alcohol and tie information, norms, and skills development to alcohol use.

REFERENCES

Bauman, K.E., Ennett, S.T., Foshee, V.A., Pemberton, M., King, T.S., and Koch, G.G. (2002). Family matters: A family-directed program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Health Promotion Practice, 2(1), 81-96.

Bauman, K.E., Foshee, V.A., Ennett, S.T., Pemberton, M., Hicks, K.A., King, T.S., and Koch, G.G. (2001). Influence of a family program on adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. American Journal of Public Health, 91(4), 604-610.

Bell, R., Ellickson, P., and Harrison, E. (1993). Do drug prevention effects persist into high school? How project ALERT did with ninth-graders. Preventive Medicine, 22, 463-483.

Botvin, G.J., Baker, E., Botvin, E.M., Filazzola, A.D., and Millman, R.B. (1984). Prevention of alcohol misuse through the development of personal and social competence: A pilot study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 45, 550-552.

Botvin, G.J., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L., Botvin, E.M., and Diaz, T. (1995). Long-term followup results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273(14), 1106-1112.

Botvin, G.J., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L., Tortu, S., and Botvin, E.M. (1990). Preventing adolescent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive-behavioral approach: Results of a three-year study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58, 437-446.

Botvin, G.J., Batson, H., Witts-Vitale, S., Bess, V., Baker, E., and Dusenbury, L. (1989a). A psychosocial approach to smoking prevention for urban black youth. Public Health Reports, 104, 573-582.

Botvin, G.J., Dusenbury, L., Baker, E., James-Ortiz, S., and Kerner, J. (1989b). A skills training approach to smoking prevention among Hispanic youth. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12, 279-296.

Botvin, G.J., Dusenbury, L., Baker, E., James-Ortiz, S., Botvin, E.M., and Kerner, J. (1992). Smoking prevention among urban minority youth: Assessing effects on outcome and mediating variables. Health Psychology, 11(5), 290-299.

Botvin, G.J., and Eng, A. (1982). The efficacy of a multicomponent approach to the prevention of cigarette smoking. Preventive Medicine, 11, 199-211.

Botvin, G.J., Renick, N.L., and Baker, E. (1983). The effects of scheduling format and booster sessions on a broad-spectrum psychosocial smoking prevention program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 6, 359-379.

Botvin, G.J., Schinke, S.P., Epstein, J.A., and Diaz, T. (1994). Effectiveness of culturally-focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority youths. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 8, 116-127.

Bry, B.H., and Slechta, C.A. (2000). Research evidence for home-based, school, and community interventions. In N. Boyd-Franklin and B.H. Bry, Reaching out in family therapy: Home-based, school, and community interventions (pp. 181-201). New York: Guilford Press.

Catalano, R.F. (1993). Prevention column: Parents: A formidable key in preventing teen substance use. Adolescent Magazine, 6(4), 16-17.

Dielman, T.E., Shope, J.T., Butchart, A.T., and Campanelli, P.C. (1986). Prevention of adolescent alcohol misuse: An elementary school program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 11(2), 259-284.

Dielman, T.E., Shope, J.T., Leech, S.L., and Butchart, A.T. (1989). Differential effectiveness of an elementary school-based alcohol misuse prevention program by type of prior drinking experience. Journal of School Health, 59, 255-263.

Donaldson, S.I., Graham, J.W., and Hansen, W.B. (1994). Testing the generalizability of intervening mechanism theories: Understanding the effects of adolescent drug use prevention interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17(2), 195-216.

Dusenbury, L. (2000). Family-based drug abuse prevention programs: A review. Journal of Primary Prevention, 20, 337-352.

Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., and Hansen, W.B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18, 237-256.

Ellickson, P.L., and Bell, R.M. (1990). Drug prevention in junior high: A multi-site longitudinal test. Science, 247, 1299-1305.

Ellickson, P.L., Bell, R.M., and Harrison, E.R. (1993). Changing adolescent propensities to use drugs: Results from Project ALERT. Health Education Quarterly, 20, 227-242.

Ennett, S.T., Bauman, K.E., Pemberton, M., Foshee, V.A., Chuang, Y., King, T.S., and Koch, G.G. (2001). Mediation in a family-directed program for prevention of adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Preventive Medicine, 33, 333-346.

Gorman, D.M., and Speer, P.W. (1996). Preventing alcohol abuse and alcohol related problems through community intervention: A review of evaluation studies. Psychology and Health, 11, 95-131.

Hansen, W.B. (1996). Pilot test results comparing the All Stars program with seventh-grade D.A.R.E.: Program integrity and mediating variable analysis. Substance Use and Misuse, 31(10), 1359-1377.

Hansen, W.B., and Graham, J.W. (1991). Preventing alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: Peer pressure resistance training vs. establishing conservative norms. Preventive Medicine, 20, 414-430.

Hawkins, D.J., Catalano, R.F., and Miller, J. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. American Psychological Association Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64-105.

Hingson, R.H., Howland, J., Schiavone, T., and Damiata, M. (1990). The Massachusetts saving lives program: Six cities widening the focus from drunk driving to speeding, reckless driving, and failure to wear seat belts. Journal of Traffic Medicine, 18, 123-132.

Holder, H.D., Saltz, R.F., Grube, J.W., Treno, A.J., Reynolds, R.I., Voas, R.B., and Gruenewald, P.J. (1997). Overall results and observations: Summing up: Lessons from a comprehensive community prevention trial. Addiction, 92, S293-S301.

Jackson, C., Henriksen, L., and Dickinson, D. (1999). Alcohol-specific socialization, parenting behaviors and alcohol use by children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60, 362-367.

Komro, K.A., Perry, C.L., Murray, D.M., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Williams, C.L. and Anstine, P.S. (1996). Peer planned social activities for the prevention of alcohol use among young adolescents. Journal of School Health, 66(9), 328-333.

Komro, K.A., Perry, C.L., Veblen-Mortenson, S., and Williams, C.L. (1994). Peer participation in Project Northland: A communitywide alcohol use prevention project. Journal of School Health, 64, 318-322.

Komro, K.A., Perry, C.L., Williams, C.L., Stigler, M.H., Farbakhsh, K., and Veblen-Mortenson, S. (2001). How did Project Northland reduce alcohol use among young adolescents? Analysis of mediating variables. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 16(1), 59-70.

Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J.D., Spoth, R., Haggerty, K.P., and Zhu, K. (1997). Effects of a preventive parent-training intervention on observed family interactions: Proximal outcomes from preparing for the drug free years. Journal of Community Psychology, 25(4), 277-292.

Maguin, E., Zucker, R.A., and Fitzgerald, H.E. (1994). The path to alcohol problems through conduct problems: A family based approach to very early intervention with risk. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4, 249-269.

Nye, C., Zucker, R., and Fitzgerald, H. (1995). Early intervention in the path to alcohol problems through conduct problems: Treatment involvement and child behavior change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 831-840.

Olds, D. (1997). The prenatal/early infancy project: Fifteen years later. In G.W. Albee and T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Primary prevention works (pp. 41-67). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Park, J., Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J.D., Haggerty, K.P., Duncan, T.E., Duncan, S.C., and Spoth, R. (2000). Effects of the preparing for the drug free years curriculum on growth in alcohol use and risk for alcohol use in early adolescence. Prevention Science, 1(3), 125-138.

Pentz, M.A., Dwyer, J.H., MacKinnon, D.P., Flay, B.R., Hansen, W.B., Wang, E.Y.I., and Johnson, C.A. (1989). A multi-community trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse: Effects on drug use prevalence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 261(22), 3259-3266.

Pentz, M.A., Trebow, E.A., Hansen, W.B., MacKinnon, D.P., Dwyer, J.H., and Johnson, C.A. (1990). Effects of program implementation on adolescent drug use behavior. Evaluation Review, 14(3), 264-289.

Perry, C.L., Grant, M., Ernberg, G., Florenzano, R.U., Langdon, M.D., Blaze-Temple, D., Cross, D., Jacobs, D.R., Myeni, A.D., Waahlberg, R.B., Berg, S., Andersson, D., Fisher, K.J., Saunders, B., and Schmid, T. (1989). W.H.O. collaborative study on alcohol education and young people: Outcomes of a four-country pilot study. International Journal of Addictions, 24(12), 1145-1171.

Perry, C.L., Williams, C.L., Komro, K.A., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Stigler, M.H., Munson, K.A., Farbakhsh, K., Jones, R.M., and Forster, J.L. (2002). Project Northland: Longterm outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Education Research, 16(5), 101-116.

Perry, C.L., Williams, C.L., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Toomey, T., Komro, K.A., Anstine, P.S., McGovern, P.G., Finnegan, J.R., Forster, J.L., Wagenaar, A.C., and Wolfson, M. (1996). Project Northland: Outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 86(7), 956-965.

Rohrbach, L.A., Johnson, C.A., Mansergh, G., Fishkin, S.A., and Neumann, F.B. (1997). Alcohol-related outcomes of the day one community partnership. Evaluation and Program Planning, 20(3), 315-322.

Ross, L.T., and Hill, E.M. (2001). Drinking and parental unpredictability among adult children of alcoholics: A pilot study. Substance Use and Misuse, 36, 609-638.

Shope, J.T., Copeland, L.A., Marcoux, B.C., and Kamp, M.E. (1996). Effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program. Journal of Drug Education, 26(4), 323-337.

Spoth, R., Guyll, M., and Day, S.X. (2002). Universal family-focused interventions in alcohol-use disorder prevention: Cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses of two interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 219-228.

Taylor, B., Graham, J.W., Cumsille, P., and Hansen, W.B. (2001). Modeling prevention program effects on growth in substance use: Analysis of five years of data from the adolescent alcohol prevention trial. Prevention Science, 1(4), 183-197.

Tobler, N.S., Roona, M.R., Ochshorn, P., Marshall, D.G., Streke, A.V., and Stackpole, K.M. (2000). School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 20, 275-336.

Toomey, T.L., Williams, C.L., Perry, C.L., Murray, D.M., Dudovitz, B., and Veblen-Mortenson, S. (1996). An alcohol primary prevention program for parents of seventh-graders: The amazing alternatives! Home Program. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 5, 35-53.

Veblen-Mortenson., S., Rissel, C.E., Perry, C.L., Forster, J., Wolfson, M., and Finnegan, J.R. (1999). Lessons learned from Project Northland: Community organization in rural communities (pp. 105-117). In Neil Bracht (Ed.), Health promotion at the community level (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wagenaar, A.C., and Perry, C.L. (1994). Community strategies for the reduction of youth drinking: Theory and application. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4, 319-345.

Williams, C.L., and Perry, C.L. (1998). Lessons from Project Northland: Preventing alcohol problems during adolescence. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22(2), 107-116.

Williams, C.L., Perry, C.L., Dudovitz, B., and Veblen-Mortenson, S. (1995). A home-based prevention program for sixth-grade alcohol use: Results from Project Northland. Journal of Primary Prevention, 16, 125-147.

Williams, C.L., Perry, C.L., Farbakhsh, K., and Veblen-Mortenson, S. (1999). Project Northland: Comprehensive alcohol use prevention for young adolescents, their parents, schools, peers and communities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 13, 112-124.

Wynn, S., Schulenberg, J., Maggs, J.L., and Zucker, R.A. (2000). Preventing alcohol misuse: The impact of refusal skills and norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 36-47.