16

Youth Smoking Prevention Policy: Lessons Learned and Continuing Challenges

Paula M. Lantz

A large body of research shows that very few people in the United States initiate cigarette smoking or become habitual smokers after their teen years. Nearly 9 out of 10 current adult smokers started their tobacco use at or before age 18 (Giovino, 1999). Given the epidemiology of smoking initiation, a great deal of policy and programmatic attention has been directed toward youth smoking prevention (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 1994; Jacobson et al., 2001). Despite this strong policy focus, tobacco use among U.S. adolescents actually rose throughout most of the 1990s, until declining somewhat in the past few years. Given the wide range of interventions and policies that have been implemented—and the plethora of research that has been conducted regarding effectiveness—much can be said about the current state of youth tobacco control policy, and its triumphs and tribulations.

This chapter presents a synthesis of the burgeoning literature regarding efforts to prevent or reduce youth smoking, with an emphasis on policies and intervention strategies that have parallels in efforts to reduce alcohol consumption among minors (i.e., school-based interventions; regulation regarding youth purchase, possession, and use; advertising restrictions; mass media counter-marketing campaigns; community interventions; and comprehensive tobacco control programs). Brief summaries of the policy and evaluation literature regarding strategies aimed at youth smoking control are presented. These summaries are based primarily on other reviews that were recently published (Lantz et al., 2000; Jacobson et al., 2001) and a set of commissioned papers presented at the recent Innovations in Youth To-

bacco Control Conference, held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in July 2002 (sponsored by the University of Michigan Tobacco Research Network, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Ted Klein Youth Tobacco Research Project). This chapter concludes with a discussion of key lessons learned from youth tobacco control efforts that potentially are relevant for youth alcohol policy.

RECENT TRENDS IN SMOKING AMONG YOUTH AND YOUNG ADULTS

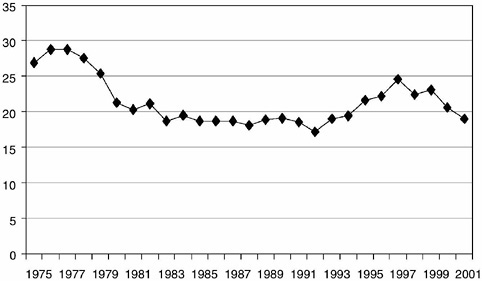

Trends in adolescent smoking typically are monitored in regard to ever smoking (also referred to as “initiation” and defined as having ever tried a cigarette), current smoking (defined as having smoked in the past 30 days), and daily smoking. Trend data regarding current smokers suggest that adolescent smoking increased during the 1960s and into the 1970s. In the late 1970s, rates began a slow yet steady decline that persisted until the late 1980s, when rates started to rise again and continued to rise for most of the decade (Jacobson et al., 2001). Data on high school seniors from 1975 to 2001 (see Figure 16-1) show that current smoking rates rose from 19.4 percent in 1990 to a peak of 24.5 percent in 1997, after which time rates

FIGURE 16-1 Prevalence of smoking in the past 30 days among twelfth graders, 1975-2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future (2002).

started to decrease slightly (Monitoring the Future, 2002; Johnston et al., 2001). Youth in all sociodemographic groups experienced increased rates of smoking during the 1990s, although in the past several years, male adolescents have had higher rates of smoking than females, and white and Native American adolescents have had higher rates than other ethnic groups.

The process of becoming a regular or habitual smoker can be considered as a series of transitions through several stages, starting with a first “initiating” puff of a cigarette (Flay, Hu, and Richardson, 1998). A clear finding from research is that smoking initiation or experimenting is a behavior of youth. Among adult smokers, the vast majority tried their first cigarette as an adolescent, and most of these initiators proceeded to the next stages in the transition to habitual smoking before the age of 19 (Giovino, 1999). The most recent estimates (from 2001) suggest that, among eighth graders, 36.6 percent have ever tried a cigarette, 12.2 percent are current smokers, and 5.5 percent are daily smokers. Among twelfth graders, 61 percent have ever smoked, 29.5 percent are current smokers, and 19 percent are daily smokers. Despite the recent declining trend, current rates are similar to what was observed for youth nearly two decades ago in the early 1980s (Monitoring the Future, 2002).

The “social context” of adolescent tobacco use is of critical importance. Socioeconomic status is associated with youth smoking, with youth from families with lower levels of parental education and income more likely to smoke (Jacobson et al., 2001; Giovino, 1999). Also, factors such as the attitudes of parents and friends/peers toward smoking, whether or not friends or peers smoke, and whether or not a parent or other family member smokes are all significantly associated with youth smoking behavior (Jacobson et al., 2001; Richter and Richter, 2001). In addition, tobacco use does tend to cluster with other types of risk behaviors—including alcohol use—among adolescents (Windle and Windle, 1999; Bauman and Phongsavan, 1999). For example, youth who smoke are more likely to engage in binge drinking (Johnson, Boles, Vaughan, and Kleber, 2000).

Smoking rates among young adults (ages 19 to 25) also rose dramatically during the 1990s. Trend data from National Health Interview Surveys suggest that current smoking rates among young adults rose from 22.9 percent in 1991 to a peak of 27.9 percent in 1999 (Lantz, 2002). Several studies suggest that this increase was observed among both college students and young adults not in school (Wechsler, Rigottu, Gledhill-Hoyt, and Lee, 1998; Johnston, O’Malley, and Bachman, 2001; Lantz, 2002). Although smoking rates among young adults also have declined recently, the dramatic increase observed during the 1990s remains alarming. Based on timeseries analysis (Lantz, 2002), it does appear that approximately 75 percent of this increase is due to a cohort effect: that is, the observed increase in smoking among young adults reflects in large part the aging of adolescent

cohorts with high rates of tobacco use. However, there is also evidence to suggest that the increase among young adults should not be dismissed totally as a cohort effect. This evidence includes an increase in the rate at which those who have experimented with tobacco become habitual smokers as young adults (especially among males), and concomitant increases in other types of substance use among adolescents and young adults in the 1990s, including binge drinking and use of marijuana and other illicit drugs (Johnston et al., 2001; Lantz, 2002). This suggests that risk-taking behavior regarding substances in general was on the rise among adolescents and young adults during the 1990s.

MAJOR YOUTH TOBACCO CONTROL STRATEGIES AND THEIR EFFECTIVENESS

School-Based Educational Interventions

During the past three decades, a number of school-based tobacco use prevention programs have been implemented, primarily at the elementary school and/or middle school level. The majority of these programs have tended to be based on one of three main approaches: (1) an information deficit or rational model in which the program provides information about the health risks and negative social consequences of tobacco use in an attempt to address “knowledge deficits,” most often in a manner intended to provoke fear, concern, or disgust; (2) an affective education model in which the program attempts to influence beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and norms related to tobacco use with a focus on enhancing self-esteem and values clarification; and (3) a social influence resistance model (Bruvold, 1993; Lantz et al., 2000). This last model emphasizes that, in addition to individual factors such as knowledge and attitudes, the social environment is a critical factor in tobacco use. Important aspects of the social environment include peer behavior and attitudes, and certain aspects of environmental, familial, and cultural contexts. Therefore, interventions based on this model focus on building skills needed to resist negative influences, including communication and decision-making skills, assertiveness training, and recognition of industry advertising tactics and peer influences. The results of several individual evaluations and meta-analyses strongly suggest that educational programs based on the social influence resistance model are the most effective of the three approaches (Bruvold, 1993; Jacobson et al., 2001; Botvin, 2000). These types of programs can have a modest but significant impact on both smoking initiation and level of use.

A recent trend in school-based interventions is the use of peer education programs (e.g., Teens Against Tobacco Use) (Black, Tobler, and Sciacca, 1998). In this type of program, older students are trained to deliver inter-

vention components to and become positive role models for middle and elementary school students. However, the long-term impact of this and other types of school-based educational interventions is of general concern because any existing effects appear to generally dissipate over a one- to four-year period (Jacobson et al., 2001). Booster interventions are needed to maintain effects over time (Botvin, 2000). Furthermore, just because an intervention is based on a social influences resistance model does not mean it will be effective. For example, studies regarding the Drug Abuse Resistance Education, or D.A.R.E.®, program (currently implemented in approximately three-fourths of the nation’s elementary schools) have been quite mixed, with the majority finding no short- and/or long-term impact on tobacco use (Ahmed, Ahmed, Bennett, and Hinds, 2002; Brown, 2001; Lynan et al., 1999; Ennett et al., 1994).

Based on the wide literature in this area, several sets of guidelines and “best practices” regarding the development, implementation, and evaluation of school-based tobacco prevention programs have been developed (IOM, 1994; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999b). In addition, however, some studies have actually shown “reverse effects” of educational interventions on youth smoking; that is, youth exposed to the intervention have significantly higher rates of smoking thereafter (Hawthorne, 1996; Ellickson and Bell, 1990). This trend has led some experts to raise concerns about the potentially counter-productive effects of educational interventions, especially those that do not include a focus on the social environment or broader community context (Peterson, Kealy, Mann, Marek, and Sarason, 2000).

Regulation, Restrictions, and Penalties Regarding Youth Access to Tobacco

In the past decade, the issue of youth access to tobacco products has received an explosion of attention. Policy action has been seen in a number of areas, including regulation of sellers, restrictions on the distribution of free products, and regulation of where and how tobacco can be sold, including efforts to restrict sales via vending machines.

Federal Public Law 102-321, enacted in 1991 and commonly referred to as the Synar amendment, stipulates that states must both (1) enforce laws restricting the sale and distribution of tobacco products to minors, and (2) demonstrate success in reducing youth tobacco access or risk not receiving the full complement of block grant funding for substance abuse prevention and treatment. The Synar amendment has led to a number of developments in youth tobacco control, including the passage of age-of-sale legislation with penalties for vendors who sell to minors and the increased use of undercover or “sting” operations (Jacobson and Wasserman, 1997).

However, few jurisdictions appear to enforce laws seriously regarding the sale of tobacco to minors. This lack of enforcement undermines the potential of such policies. Enforcement is a critical component of potential effectiveness; without ongoing enforcement, these types of laws appear to be benign (Jacobson and Wasserman, 1997; Forster and Wolfson, 1998; Stead and Lancaster, 2000). Several controlled community intervention studies have demonstrated that increased enforcement of laws regarding tobacco sales to minors can indeed reduce illegal sales (Rigotti, DiFranza, and Change, 1997; Altman, Wheelis, McFarlane, Lee, and Fortmann, 1999; Biglan et al., 1996).

Unfortunately, the evidence that a reduction in youth purchases of cigarettes actually translates into a reduction in consumption or a change in smoking behavior is limited. The majority of studies conducted in this area only explored the impact of enforcement on youth access or ability to purchase tobacco products rather than the impact on smoking rates. In studies that looked at both sales and smoking behavior, reduced sales typically did not go hand in hand with reduced smoking (Forster and Wolfson, 1998; Lantz et al., 2000). We might expect the enforcement of youth access laws to have an impact on smoking behavior if the primary way in which adolescents obtain their cigarettes is through illegal purchases. However, youth cite a number of “social sources” (such as family, friends, or even strangers) for their cigarettes in addition to illegal purchase. Thus, with the evidence to date, we can conclude that interventions that involve enforcement of state or local laws regarding tobacco sales to minors (i.e., “cracking down” on vendors) can produce reductions in illegal sales, but whether the enforcement also leads to sustained reductions in youth tobacco use remains speculative.

Penalties for Youth Possession, Use, and Purchase

A recent yet controversial response to youth tobacco use is the implementation of state and/or local laws that levy penalties against youth for the possession, use, or purchase of tobacco products. Some tobacco control advocates have stridently protested this approach as an attempt to shift attention and responsibility away from vendors who sell tobacco products to children to the minors themselves. Nonetheless, this shift in focus gained significant momentum during the 1990s. As Wakefield and Giovino (2002) reported, the number of states with legislation restricting possession of cigarettes among minors (those under age 18) grew from 6 in 1988 to 32 in 2001. In 2001, only 6 states and the District of Columbia had no laws mandating some type of penalty on youth possessing, using, or purchasing tobacco products (Wakefield and Giovino, 2002). The penalties associated with these laws vary widely, including receipt of a ticket, a fine, appearance

in court (including special “teen courts”), suspension from school, loss of driving privileges, referral to an educational or smoking cessation program, community service, and/or other court-ordered responses.

A small number of studies have been conducted to assess the impact of teen penalty laws on youth tobacco purchases and use. Wakefield and Giovino (2002) summarized the limited amount of research conducted to date:

Based on these studies, it is difficult to conclude there are strong positive effects from [possession, use, and purchase] laws. Some of the studies suggest small effects for some subgroups, such as low-risk younger students. However, in assessing the value of [these] laws, it is important to consider the net effects of [these] laws, rather than focusing upon one positive or negative aspect.

These reasons include the low likelihood of detection and thus punishment, the long time delay between detection and punishment, and the rather impersonal or distant relationship between the punisher (the state) and the youth involved.

Furthermore, concerns have been raised that possession, use, and purchase laws could actually undermine or confuse efforts being made by schools (Kropp, 1998) or may intensify parent-child relationships that are already vulnerable or troubled (Woodhouse, Sayre, and Livingood, 2001; Wakefield and Giovino, 2002). This type of regulation also raises concerns that the focus on youth relieves the tobacco industry of responsibility for its marketing tactics, and further reinforces the industry’s premise that smoking is a behavior for adults only, a perspective that likely enhances the appeal or allure of smoking for many youth. As with youth access laws, there is little evidence to suggest that this type of regulation has a significant impact on youth smoking behavior. As a result, some tobacco control experts have called for the shifting of research, intervention development, and advocacy resources away from this policy area (Ling, Landman, and Glantz, 2002; Fichtenberg and Glantz, 2002; Glantz, 1996).

Tobacco Advertising Restrictions and Mass Media Counter-Marketing Campaigns

Tobacco Advertising Restrictions

As a consumer product, cigarettes are heavily advertised and marketed. Despite the defensive claims of tobacco industry representatives that they only market to adults, a large and growing body of evidence shows that the industry has indeed developed product lines and large, intense advertising campaigns that target adolescents and even younger children (Jacobson et al., 2001). In a review of industry documents, Perry concluded that there

is significant evidence from the industry itself that: (1) youth smoking has been viewed as critical to economic viability; (2) decreases in youth smoking were perceived as negative and disturbing; and (3) specific products and advertising strategies were aimed specifically at youth, with successful results (Perry, 1999).

There is great concern that tobacco advertising and marketing—including the distribution of promotional products such as clothing, sporting equipment, and outdoor gear—are positively associated with youth smoking. There also is great concern that increased marketing activities aimed at young adults, including promotions on college campuses and at bars, nightclubs, and musical events, are partly responsible for the recent increase in smoking among young adults (Ling and Glantz, 2002; Lantz, 2002).

Estimating the effects of advertising and promotions on smoking initiation or cigarette consumption is technically difficult. Several studies have shown that the most popular cigarette brands among younger smokers are also those that are most heavily advertised (DiFranza et al., 1991; Cummings, Hyland, Pechacek, Orlandi, and Lynn, 1997; Arnett and Terhanian, 1998). Studies have also found that adolescents who are more susceptible to future tobacco or alcohol use have more favorable reactions to product advertising (Unger, Johnson, and Rohrbach, 1995). In addition, a growing amount of research evidence suggests that youth awareness of tobacco marketing campaigns, receipt of free tobacco samples, and receipt of direct mail promotional paraphernalia are associated with smoking susceptibility and initiation (Schooler, Feighery, and Flora, 1996; Gilpin and Pierce, 1997; Feighery, Borzekowski, Schooler, and Flora, 1998). Although some of the evidence to date is compelling, these studies primarily show an association rather than a causal relationship between exposure to tobacco advertising/marketing and youth smoking. Two longitudinal studies do provide evidence that exposure to tobacco industry promotional activities at a young age is associated with subsequent smoking (Pierce, Gilpin, and Choi, 1999; Pucci and Siegal, 1999). In fact, Pierce and colleagues (1999) concluded that nearly one-third of smoking experimentation among California youth between 1993 and 1996 is attributable to tobacco industry marketing and promotional tactics. Nonetheless, the potential effects of restrictions or bans on cigarette advertising on adolescent or young adult smoking behavior remain unclear at this time.

Mass Media Counter-Marketing Campaigns

Mass media strategies have been used for broad-based public education regarding a variety of public health issues, including immunizations, domestic violence, drunk driving, illicit drug use, and tobacco use. In general, mass media efforts are viewed as being especially effective in efforts to

reach youth because they tend to be more interested in and exposed to media messages. Youth have been the primary target of some forceful and sophisticated anti-tobacco media campaigns in a number of communities and states, primarily as a major part of state-funded tobacco control programs but also through the efforts of advocacy or activist groups (Jacobson et al., 2001; Farrelly, Niederdeppe, and Yarsevich, 2002b). Many of these campaigns have focused on efforts to “counter-market” the efforts of the tobacco industry to glamorize smoking and to downplay or deny the addictive, harmful nature of tobacco products (Farrelly et al., 2002b). In fact, both a campaign in Florida and a subsequent national effort launched by the American Legacy Foundation (the independent foundation established as part of the multistate settlement with the tobacco industry) have been labeled “the truth campaign” (Farrelly et al., 2002a). In addition, a number of other thematic approaches and message strategies have been or are currently being employed in campaigns at the state and local levels, including the short- and long-term consequences of smoking and changing social norms about smoking (Farrelly et al., 2002b).

Although it is difficult to evaluate the independent effects of mass media campaigns on smoking behavior, evaluation results from a number of community trials and statewide campaigns provide evidence that such interventions can be effective in reducing youth smoking. Farrelly et al. (2002b), in a recent review, concluded:

[T]here is growing evidence that aggressive youth prevention campaigns in states have been effective in reducing tobacco use, but it is still unclear to what extent increases in cigarette prices and other concurrent programs contributed to these decline … [In addition,] while counter-industry and branding approaches are fashionable, based on the experimental literature and results from recent campaigns, it is not clear if any particular message strategy dominates others (p. 14).

It appears that anti-smoking advertising campaigns aimed at youth have greater potential when reinforced by other community or school-based efforts implemented at the same time (Jacobson et al., 2001; Farrelly, Niederdeppe, and Yarsevich, 2002b). In addition, media campaigns that are theoretically driven and involve essential elements of social marketing stand the best chance of having an impact on attitudes and behaviors regarding tobacco use. The literature at hand suggests that mass media interventions increase their impact if the following conditions are met: (1) the campaign strategies are based on sound social marketing principles; (2) the effort is large and intense enough; (3) target groups are carefully differentiated; (4) messages for specific target groups resonate with “core values” of the group (rather than simply preach about the health risks of tobacco use) and are based on empirical findings regarding the needs and interests

of the group; and (5) the campaign is of sufficient duration, rather than a one-shot, limited effort (Jacobson et al., 2001).

Within the past few years, two large tobacco companies have launched their own media campaigns against youth smoking: (1) Philip Morris’ Think. Don’t Smoke, and (2) Lorillard’s Tobacco is Whacko, if You’re a Teen. Although the electronic and print ads that comprise these campaigns take a variety of forms, the core message is that smoking is an adult behavior in which kids should not engage. Based on what is known about youth smoking prevention and social marketing in general, there are many reasons to believe that the approach taken by the tobacco industry will not be effective. In fact, there are some reasons to believe that this message will serve to make smoking—as a forbidden “adult” behavior—even more appealing to youth. Farrelly and colleagues have reported that, in regard to the Philip Morris approach, exposure to the ads—which themselves are not particularly compelling to many teens—is associated with more positive attitudes toward the tobacco industry and with increased intentions regarding future smoking (Farrelly et al., 2002a; Farrelly, Niederdeppe, Yarsevich, 2002b). A developmental psychologist with experience in advertising and marketing wrote: “This [type of phenomenon] is behind the ‘don’t put peas up your nose’ phenomenon in child rearing. I do not recommend giving this command to a preschooler. And while you are at it, maybe you shouldn’t tell your teenager not to smoke” (Rust, 1999, p. 87). Thus, a cynic might suggest that the tobacco industry—with a primary interest in increasing industry credibility—knows full well that this approach to youth smoking prevention is at best benign, and may actually have counterproductive effects (Jacobson et al., 2001; Novelli, 1999).

Tobacco Excise Taxes

As a policy strategy, tobacco taxation not only generates revenue for federal, state, and some local governments, it also creates an economic disincentive to use tobacco products. Theoretically, increasing the price of cigarettes through taxation could reduce adolescent consumption through three main mechanisms: (1) serving as an inducement to quit smoking; (2) serving as an inducement to reduce the amount smoked; and (3) preventing some youth from starting to smoke (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1994). The extent to which higher cigarette taxes actually prompt these mechanisms depends on how responsive smokers and potential smokers are to price increases.

A number of economic studies of consumer responsiveness to cigarette pricing (or “price elasticity of demand”) have been conducted, although the majority have focused on the adult or overall demand for cigarettes, with

comparatively few focused on youth. The conclusion of numerous studies is that an increase in the price of cigarettes does lead to lower consumption by adults (Chaloupka and Warner, 2000). Although the evidence on the degree to which teenagers are responsive to changes in cigarette prices is a bit more mixed, the general consensus is that higher prices are an effective deterrent to youth smoking (Jacobson et al., 2001; Lantz et al., 2000). In fact, several studies have found an inverse relationship between price sensitivity and age, meaning that youth are more sensitive to cigarette prices than are adults (Farrelly and Bray, 1998; Lewit et al., 1997; Dee and Evans, 1998).

Because most excise tax increases in the United States have been relatively small to date, it is difficult to predict the exact impact that a large tax increase (e.g., $1 or more per pack) would have on youth smoking. One might assume that the effects would be proportionately greater than those of a smaller tax increase, but this is not certain. Nonetheless, the evidence to date does suggest that tobacco excise tax increases are an effective policy strategy for reducing youth smoking.

Smoke-Free Space Policies

Policy efforts to restrict smoking in public spaces—including airplanes, public/government buildings, worksites, hospitals, restaurants, bars, and hotels—have proliferated since the 1980s. The primary purpose of these bans is to reduce exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. These types of policies also are believed to impact smoking behavior. Theory suggests that the main reasons smoking bans could affect behavior are because they reduce opportunities for smoking, they provide further incentive to quit for those who are contemplating cessation, and they help to create and reinforce social norms against smoking. Several studies have shown that these types of “clean air” policies do have an impact on adult smoking, and can be implemented without negative economic repercussions (Brownson et al., 1997; Glantz and Charlesworth, 1999; Glantz, 1999).

The impact of smoke-free space policies on youth is less clear. However, a few studies have found evidence that clean indoor air laws do reduce teenage cigarette consumption (Chaloupka and Grossman, 1996; Wasserman, Newhouse, and Winter, 1991). It also appears that youth are positively affected by school-based policies regarding tobacco use (Wakefield et al., 2000; Pinilla et al., 2002; Chaloupka and Grossman, 1996; Pentz et al., 1989a). Schools may have their own smoking policies, responding to violations with a variety of penalties, including fines, smoking education and cessation classes, informing the student’s parents, suspension and/or expulsion, and community service assignments. These policies clearly are aimed at youth, but can restrict smoking behavior among adults as well. As

with other types of tobacco-related policies, it appears that school-based policies need to be enforced to be effective. As Moore, Roberts, and Tudor-Smith (2001) documented, the prevalence of smoking among students is associated with the presence of a smoking policy and the strength of its enforcement. There is some evidence to suggest that an increasing number of primary and secondary schools are developing and implementing smoking policies, and are also more actively enforcing these policies (Jacobson et al., 2001). In addition, over the past decade, a number of college and university campuses have implemented full or partial smoking bans. The creation of smoke-free environments on campus (including dormitories and other residence facilities, cafeterias, recreational areas, classrooms, and private offices) is in direct response to concern about the increase in smoking among college students (Wechsler et al., 2001). Chaloupka and Wechsler (1997) found that rates of smoking among college students were lower in the presence of policies restricting smoking on campus and in nearby restaurants. Again, however, these types of policies must be promoted and enforced to be effective.

An emerging area of interest is family or home-based smoking policies. Although few studies have been conducted on this topic to date, early research results suggest that having an articulated set of rules regarding smoking in the home environment has a negative impact on youth smoking behavior (Biglan et al., 1996; Spoth, Redmond, and Shin, 2001).

Smoking Cessation Interventions

In the face of rising smoking rates among adolescents, and with growing empirical evidence regarding the limitations of a number of primary prevention strategies, interest in the efficacy of youth smoking cessation interventions has grown over the past decade. A number of descriptive survey and focus group studies clearly show that many teen smokers are indeed motivated to quit (Jacobson et al., 2001). For example, in a sample of high school seniors, nearly 70 percent of regular smokers had tried to quit at least once, and 60 percent had attempted to quit in the past year (Burt and Peterson, 1998). Success in quit attempts, however, is quite low among adolescents (Mermelstein, 2002). Many youth also apparently believe that quitting is something done all alone and “cold turkey.” Most adolescent smokers are unfamiliar with the concept of a smoking cessation program or with methods available to support quit attempts; those who are aware tend to express concern regarding confidentiality and the involvement of parents in their cessation effort (Jacobson et al., 2001).

The psychology and physiology of nicotine dependence in adolescents are not well understood, nor is the impact of smoking cessation interventions in this population (Mermelstein, 2002; Jacobson et al., 2001; Sussman,

2002). None of the pharmacological interventions and nicotine replacement therapies currently on the market have been approved for use under the age of 18. Mermelstein (2002, p. 6) summarized the state of knowledge regarding teen smoking cessation by stating that the “evidence base behind smoking cessation interventions for adolescents is starting to grow, but unfortunately, the studies to date have frequently been plagued by major methodological problems,” including lack of control or comparison groups, inappropriate measures of cessation, follow-up periods that are too short, and vague descriptions of interventions.

Based on the evidence at hand, it does appear that some cessation interventions aimed at adolescents have met with some limited success. Sussman (2002) estimated average quit rates across a number of studies, and found that the immediate post-program quit rate for those receiving the intervention was double that for those in the control groups (14 percent versus 7 percent). This average quit rate, however, is much lower than that observed for adults, and is for immediately after the program ended and thus does not speak to either short-term or long-term sustainability. At the present time, many researchers and tobacco policy experts remain speculative or “cautiously optimistic” about the potential of smoking cessation interventions for adolescents. To date, only two studies regarding the nicotine patch have been conducted on minors, and both produced very low cessation rates (Hurt et al., 2000; Smith et al., 1996). Although it is premature to state “best practices” and to make policy recommendations in this area, Mermelstein (2002) did conclude:

[C]ognitive-behavioral approaches that emphasize skills training and self-management approaches may hold promise, along with perhaps brief motivational interviewing procedures in the context of health care delivery settings there is much promise, though, for “more and better to come” as almost two dozen well-designed trials are currently underway (p. 2).

The Case for Community Interventions and Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs

In-depth review of the current state of youth tobacco policy suggests that a number of prevention strategies are promising, especially if conducted in a coordinated way to take advantage of potential synergies across interventions (Jacobson et al., 2001). For example, research suggests that mass media interventions are most potent when implemented in conjunction with school-based efforts or community interventions (Farrelly, Niederdeppe, and Yarsevich, 2002b). Research also shows that school-based educational interventions are enhanced when supported by community interventions that target the social environment. In addition, it is clear that secondary prevention efforts (e.g., tobacco use cessation) need to

complement primary prevention strategies because primary prevention fails with a significant number of youth.

The increased understanding of the combined effects of individual factors and social environment conditions on tobacco use has resulted in an emphasis on community interventions. In general, community interventions have multiple components that target a community at a number of different levels, including individuals, institutions, policies, and the broad social environment. Typical or common elements include an emphasis on altering the social environment or social context in which tobacco products are obtained and used, with the shared goal of creating an environment that is supportive of nonsmoking and cessation. Intervention activities can involve families, schools, community organizations, houses of worship, businesses, the media, social service and health agencies, government, and law enforcement, with intervention strategies generally focused on making changes at both the individual and the environmental levels (Jacobson et al., 2001). Some examples of community interventions targeting tobacco use include COMMIT (Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation), Project ASSIST (American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention), and the Fighting Back program (Jacobson et al., 2002).

Although a number of communities have implemented multiple-component, community-focused interventions to reduce youth tobacco use, only a handful of published reports exist of evaluations using research designs that employ the use of a control or comparison group. Nonetheless, the research results that are available are encouraging in some cases. For example, a community intervention implemented in 15 communities in the Kansas City area incorporated mass media, school-based education, parent education, community organizing, and policy advocacy, and was found to significantly reduce tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use among youth. In specific regard to youth smoking, rates of current smoking were 19 percent in the targeted communities compared to 29 percent in the control communities two years after the intervention (Pentz et al., 1989b, 1989c). Positive evaluation results were also reported from the Class of 1989 Study (which was part of a larger community intervention called the Minnesota Heart Health Program) and an intervention in rural Oregon (Perry et al., 1992; Biglan et al., 1999).

There is a significant difference between “community-focused” or “community-placed” interventions and true “community-based” interventions. Interventions that target a specific community and attempt to reach diverse audiences through multiple channels within that community need to be designed and implemented with a strong community perspective. The best way to achieve this community perspective is to ensure that the intervention and all of its component parts are actually designed and planned by people from the community receiving the intervention, rather than by out-

side “experts” who likely do not fully understand the specific historical, cultural, socioeconomic, and political contexts of the community, or the best ways in which to build on the strengths or assets that already exist within it. The perspectives and principles of “community-based participatory research”—in which members of a community share full power and control in all stages of the design, implementation, and evaluation of an intervention—are critical for community-based efforts in youth tobacco control (Israel et al., 1998; Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995).

In summary, community-based interventions that work through parents/families, schools, the local media, and community-based organizations appear to have a stronger impact when they work in tandem over time rather than as single or separately implemented interventions (Jacobson et al., 2001). However, the results of the few controlled trials of community interventions that are available also suggest that most community interventions likely are insufficient to bring about dramatic and sustained declines in youth tobacco use. To produce significant and long-lasting effects, community interventions need to be combined with taxation, strong advocacy work aimed at policy and social environment change, and strong and sustained mass media strategies.

Increased understanding from community intervention studies, along with the availability of resources in most states from increases in the state tobacco excise taxes and/or from the Master Settlement Agreement, has fueled the development of coordinated state-based efforts in youth tobacco control. Over the past decade, several state health departments have implemented what is referred to as “comprehensive tobacco prevention and control programs.” These state programs are comprehensive in that they employ a variety of strategies to reach a number of different audiences; they incorporate multiple types of interventions at the regional, state, and local levels; and they attempt to have a strong policy component (Jacobson et al., 2002; Wakefield and Chaloupka, 2000). “Best practices” for this type of comprehensive tobacco control program have been summarized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 1999a). Recommended components of a comprehensive program include the following: (1) a statewide focus; (2) community-based interventions; (3) school-based interventions; (4) counter-marketing media activities; (5) cessation programs; (6) enforcement of existing laws and policies; (7) intervention programs aimed at chronic diseases caused by tobacco use; (8) surveillance and evaluation efforts; and (9) dedicated administration and management.

Although many comprehensive state programs are in the early stages of development and implementation, these comprehensive models—when sufficiently funded and at a significant level of intensity—have great potential for youth tobacco control. CDC developed model components based on the experiences of two states: California and Massachusetts. The California

Tobacco Control Program began in 1989, funded by Proposition 99, which raised the state tax on cigarettes from 10 to 35 cents. The goal of the program is to decrease smoking among both adolescents and adults. The program has multiple components (which have changed somewhat over the years), including a large, hard-hitting mass media campaign with multiple themes and messages; investments in the tobacco control capacity of local and city health departments; school-based interventions; a number of cessation efforts; and other strategies aimed at identified subpopulations through diverse channels. More recent efforts have concentrated on three main goals: (1) to reduce exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, (2) to reduce youth access, and (3) to counter protobacco influences (Pierce et al., 1998; Jacobson et al., 2001).

The Massachusetts Tobacco Control program also was funded through an increase in the state tobacco excise tax, which was passed in November 1992. A key component of the program is a statewide multimedia campaign with a number of themes and strategic messages. Other activities have included a telephone hotline to support cessation, a Tobacco Education Clearinghouse, providing technical support for capacity building in local health agencies and primary care facilities, school-based educational efforts, and activities restricting youth access (Biener, 1999). More recently, Florida was able to increase its youth tobacco control efforts after receiving the first installment of the settlement of the Medicaid litigation with the tobacco industry. The Florida program includes a strong marketing component (including the “truth” campaign described earlier). Other components include funding of community partnerships and community-based activities, youth programs, enforcement of youth access laws, and a strong evaluation effort (Jacobson et al., 2001).

A number of analyses and evaluations of the comprehensive programs implemented in California, Massachusetts, and Florida have been conducted, with a full review of research findings to date outside the scope of this chapter. In summary, however, there is substantial evidence that these programs can have an impact on tobacco use among both youth and adults (Jacobson et al., 2001). The rate of adolescent smoking in California dropped by 12 percent between 1995 and 1997, when smoking was increasing among youth nationally (Independent Evaluation Consortium, 1998; Pierce et al., 1998). During its first 9 years, the California program prevented an estimated 30,000-plus deaths from tobacco-related heart disease (Fichtenberg and Glantz, 2002). Not all evidence, however, points to a significant impact of the comprehensive efforts on youth. Rohrbach and colleagues (2002) recently reported that, in a survey of tenth graders in 84 randomly selected schools, there was no association between exposure to California Tobacco Control Program components and tobacco-related attitudes and behaviors.

Rates of smoking among both adults and adolescents in Massachusetts dropped after the state’s comprehensive tobacco control program was implemented. Between 1992 and 1996, per capita consumption dropped 6.1 percent nationally but 19.7 percent in Massachusetts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996; Biener, 1999). Florida also has witnessed startling and impressive declines in youth smoking. In a 1-year period (February 1998 to February 1999), the 30-day prevalence of smoking among teens dropped from 25.2 percent to 20.9 percent, with declines observed for both genders and all ethnic groups (Florida Department of Health, 2000). Analyses have shown that combining tax increases with other interventions leads to reductions in both adolescent and adult smoking above and beyond what price increases would do alone (Hu, Sung, and Keeler, 1995; Wakefield and Chaloupka, 2000). Lessons regarding the political nature of these programs also have been documented (Pierce et al., 1998; Balbach and Glantz, 1998; Siegel et al., 1997).

DISCUSSION: LESSONS FOR YOUTH ALCOHOL POLICY

The most obvious conclusion from this review is that adolescent smoking prevention efforts have had mixed results, and that there is no “magic bullet” in terms of youth tobacco control on the horizon (Jacobson et al., 2001). As a result, the position that a significant amount of policy attention and resources should be directed at youth smoking prevention is somewhat controversial. Some policy analysts have suggested that the emphasis on youth may actually have counterproductive effects, making smoking more rather than less attractive to them (Glantz, 1996; Hill, 1999). Others have suggested that because primary prevention strategies have met with only limited success, efforts should be focused on secondary prevention, specifically in interventions aimed at getting teens and young adults who smoke to quit. Still others have suggested that the most fruitful approach to tobacco control is to focus on cessation interventions and smoke-free policy interventions in the adult population (Hill, 1999). Jacobson et al. (2001) suggested that these different policy views are not mutually exclusive, and that multiple approaches—aimed at both adolescents and adults, and focusing on both primary and secondary prevention—can be implemented simultaneously. In addition, many of these interventions have great potential to be cost-effective because even modest intervention effects among youth could lead to significant reductions in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality across the life course. Nonetheless, the relative focus of resources and policy attention on adolescents versus adults and on primary versus secondary prevention remains under debate.

Brief comments on the state of knowledge for several major areas of youth tobacco control and some broad implications for youth alcohol policy

follow. First, it is clear that comprehensive programs involving a number of efforts targeted locally but coordinated at the state level are key. A number of different strategies—aimed at individual, family, institutional, community, and policy levels—need to be implemented simultaneously. As mentioned earlier, CDC recommends several components as critical in a comprehensive youth tobacco control program, all of which have parallels in efforts to reduce underage drinking. These components include implementing effective community-based and school-based interventions in a social context that is being hit with a strong media campaign (aimed at some set of “core values”) and with an effort to vigorously enforce existing policies regarding the purchase, possession, and use of the substance. In addition, excise taxes are believed to be very effective in reducing youth smoking, although the exact mechanism(s) by which they work is not known. Nonetheless, increasing the price of cigarettes through an increase in taxes is currently viewed as a cornerstone of youth tobacco control policy. An increase in the tobacco tax can have independent effects above and beyond that of other interventions being implemented simultaneously, and—if the political climate allows—also can be used a source of revenue to fund other tobacco control interventions. Evidence exists to suggest that adolescents are also sensitive to tax increases that raise the price of alcohol (Cook and Moore, 2002).

There is not a “one size fits all” comprehensive tobacco control program. States are currently experimenting with combinations of a number of different strategies at the state and local levels. In regard to school-based interventions, we know that these efforts need to meet several criteria to be effective, including the use of a social resistance model, the recognition of the importance of social context regarding attitudes and policies toward smoking, and program boosters throughout high school. These criteria hold for interventions targeting alcohol and illicit drugs as well. In addition, however, concern has been expressed recently that some school-based interventions are not only benign, but may actually produce reverse or counterproductive effects.

Why these reverse effects might occur is not clear, but a major hypothesis is that youth hear negative things about smoking in school yet often witness people using tobacco in their homes, communities, and the media, creating an aura of hypocrisy around the intervention message. In addition, it is also hypothesized that youth frequently receive the message that they should not smoke because they are kids, a message that casts smoking as an “adult behavior” and likely makes it even more attractive. Similar, and perhaps even heightened, concerns could be raised regarding school-based alcohol prevention efforts that cast drinking as an adult behavior. The “hypocrisy” concern—that the messages youth receive about not drinking occur in a broader social environment in which alcohol use is extremely

prevalent and positively presented—is great, as is concern about the potentially counterproductive effects of the message that drinking is fine for adults but not for anyone under the age of 21.

The evidence regarding youth access regulations, restrictions, and penalties at the state and local levels suggests that such policy efforts do reduce access because—when enforced—they do reduce illegal purchases by minors. As mentioned, enforcement of regulations and policies on the books is considered a critical component of a comprehensive state tobacco control program. However, there is little evidence that reduced access to tobacco through enforcement of purchase, use, or possession laws has a concomitant reduction on adolescent smoking behavior. In fact, there is a growing call in the tobacco control community to abandon this type of policy strategy, and to redirect research and advocacy resources toward avenues that appear to have greater potential for actually reducing tobacco use. The amount of time, energy, and money involved with passing these types of laws and then making sure they are enforced is quite significant, and is viewed by some as an unproductive drain on the limited financial and human resources available for tobacco control. Others, however, believe such interventions should remain a focal point of efforts. These are important issues and debates that should be considered by youth alcohol policy experts as well. Obviously, continual efforts need to be made to enforce laws regarding the purchase of alcohol by minors in stores, bars, and restaurants. The question, however, is what the relative degree of focus on this policy area in a comprehensive alcohol control program should be. In the tobacco control community, a primary concern among some experts is that a disproportionate amount of attention and resources has gone to implementing sting operations and other types of interventions when there is no evidence that reducing illegal sales/purchases actually translates into decreased smoking rates.

Regarding the media, the effects of restrictions on advertising or promotional strategies are not clear at the present time, although there is evidence that industry marketing does have an impact on the attitudes and behaviors of youth regarding smoking. In addition, specific types of counter-marketing campaigns are proving to have a significant and important impact on youth smoking. Hard-hitting campaigns that include pointed messages about industry manipulation of information about what is in cigarettes and about the health effects of smoking are viewed as having great potential. The ability of these types of campaigns to have a sustained impact, however, is not clear. Regarding youth alcohol prevention, it is not clear if a similar type of campaign—one that included hard-hitting messages regarding deceptive and manipulative behavior on the part of the alcohol industry—could be waged in a legitimate and successful fashion. Messages

regarding alcohol (including the messages in campaigns launched by the industry) are to drink responsibly as an adult, but to not drink as a minor. It seems within the realm of possibility that campaigns that attempt to reduce alcohol use among youth by emphasizing that drinking is an “adult behavior”—whether implemented by the industry or others—run the same risks as those promoting smoking as an adult choice. The effects, at best, are likely to be benign, but also could be counterproductive.

Another important component of current tobacco control strategies (for both youth and adults) is the promotion of smoke-free spaces through regulation at the state and local levels. An important aspect of these types of policies is that they provide strong social cues or messages about the social acceptance of smoking, thus reinforcing some of the messages youth are getting through school-based and other types of interventions. Both advocacy work and research in this area currently are considered important components of youth tobacco control. The role of this type of policy action in youth alcohol control, however, is less clear. Although smoke-free policies are considered critical because of their impact on social norms and the social environment, they are also politically feasible because they serve to decrease exposure to second-hand smoke (i.e., they help to decrease potential health threats that smokers cause to nonsmokers). The obvious parallel in alcohol use is drinking and driving. Policies that restrict alcohol consumption in order to protect others from the threats posed by drunk drivers are broadly supported and politically acceptable. Yet, given the pervasiveness of alcohol consumption in our society, it is unlikely that many communities would consider total bans on adult alcohol consumption at restaurants and other types of public places (e.g., sports arenas, hotels, airplanes). In terms of families enforcing social norms, alcohol-free homes are not likely to be as pervasive as smoke-free homes. Nonetheless, home-based alcohol policies could convey what is considered to be appropriate and acceptable alcohol usage by all family members both within and outside of the home, and what the consequences are for violating the home policy.

As mentioned earlier, there is some tension in the tobacco control community regarding the relative emphasis that should be placed on primary versus secondary prevention. In the case of youth tobacco control, secondary prevention primarily means clinical interventions regarding cessation. By the time they reach high school, many youth have not only tried smoking but are already either physiologically or psychologically addicted to cigarettes. At this point, tobacco use prevention messages are irrelevant. Given the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions for adults, and the large number of addicted teenagers, cessation programs tailored to youth are seen as a critical part of a comprehensive tobacco control program. Nonetheless, there is debate on how much emphasis should be placed

on this component relative to others. In addition, the research literature to date does not suggest that there is a number of effective methods for smoking cessation among adolescents.

As with tobacco, there is some tension between primary and secondary prevention in regard to youth alcohol use. Because alcohol is an addictive substance, and youth can come to abuse alcohol early in their drinking careers, secondary prevention should involve clinical interventions for youth with diagnosed drinking problems. However, a greater degree of tension is likely to involve the appropriate relative degree of emphasis on youth who have not initiated drinking (primary prevention) and youth who have already tried alcohol and are considered “current” drinkers (have had some alcohol in the past 30 days). The relative focus on these two areas should be informed by the degree of success seen by primary versus secondary prevention interventions. As mentioned, some people (tobacco control advocates) have expressed a sense of defeat regarding the primary prevention of youth smoking, and thus believe a more effective strategy will be to concentrate on new methods for secondary prevention among adolescents and young adults.

CONCLUSION

Trends in youth smoking paint a frustrating picture for public health. Clearly there have been ups and downs in the fight against adolescent tobacco use. However, at a time when the health hazards of smoking are widely accepted and understood, and when significant resources already have been invested in program and policy responses, youth smoking rates are disturbingly high. The decline in smoking rates in the past few years is indeed encouraging. Nonetheless, many policy makers, tobacco control experts, and public health advocates are taking a serious and critical look at where investments have been made and what these investments have reaped. The result, as described in this chapter, is some degree of consensus on the types of interventions with the greatest potential, yet also some disagreement about how limited human and financial resources are best invested in the future.

The tobacco control community has learned a great deal from efforts made in other areas of substance abuse, including youth alcohol control. Hopefully, some of the knowledge gained by the ongoing and intensive efforts made in youth smoking prevention—knowledge gained from intervention development and evaluation, other types of research, litigation, advocacy work, and political struggles—will be instructive for youth alcohol policy as well.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, N.U., Ahmed, N.S., Bennett, C.R., and Hinds, J.E. (2002). Impact of a Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program in preventing the initiation of cigarette smoking in fifth- and sixth-grade students. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(4), 249-256.

Altman, D.G., Wheelis, A.Y., McFarlane, M., Lee, H., and Fortmann, S.P. (1999). The relationship between tobacco access and use among adolescents: A four community study. Social Science and Medicine, 48(6), 759-775.

Arnett, J.J., and Terhanian, G. (1998). Adolescents’ responses to cigarette advertisements: Links between exposure, liking, and the appeal of smoking. Tobacco Control, 7, 129-133.

Balbach, E.D., and Glantz, S.A. (1998). Tobacco control advocates must demand high-quality media campaigns. Tobacco Control, 7, 397-408.

Bauman, A., and Phongsavan, P. (1999). Epidemiology of substance use in adolescence: Prevalence, trends and policy implications. Drugs and Alcohol Dependence, 55(3), 187-207.

Biener, LW. (1999). Progress toward reducing smoking in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from 1993 through FY 1999. Boston: University of Massachusetts at Boston, Center for Survey Research.

Biglan, A., Ary, D., Yudelson, H., Duncan, T.E., Hood, D., James, L., Koehn, V., Wright, Z., Black, C., Levings, D., Smith, S., and Gaiser, E. (1996). Experimental evaluation of a modular approach to mobilizing anti-tobacco influences of peers and parents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(3), 311-339.

Biglan, A., Ary, D.V., Smolkowski, K., Duncan, T., and Black, C. (1999, August). A randomized controlled trial of a community intervention to prevent adolescent tobacco use. Center for Community Interventions on Childrearing, Oregon Research Institute, Eugene, Oregon. Unpublished paper.

Black, D.R., Tobler, N.S., and Sciacca, J.P. (1998). Peer helping/involvement: An efficacious way to meet the challenge of reducing alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among youth? Journal of School Health, 68(3), 87-93.

Botvin, G.J. (2000). Preventing drug abuse in schools: Social and competence enhancement approaches targeting individual-level etiologic factors. Addictive Behaviors, 25(6), 887-897.

Brown, J.H. (2001). Youth, drugs, and resilience education. Journal of Drug Education, 31(1), 83-122.

Brownson, R.C., Eriksen, M.P., Davis, R.M., and Warner, K.E. (1997). Environmental tobacco smoke: Health effects and policies to reduce exposure. Annual Review of Public Health, 18, 163-185.

Bruvold, W.H. (1993). A meta-analysis of adolescent smoking prevention programs. American Journal of Public Health, 83(6), 872-880.

Burt, R.D., and Peterson, A.V. (1998). Smoking cessation among high school seniors. Preventive Medicine, 27, 319-327.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1996). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 45(SS04), 181-184.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999a). Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Smoking and Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999b). Tobacco use prevention curriculum and evaluation fact sheets. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dash/rtc/tob-curric.htm. Accessed October, 2002.

Chaloupka, F.J., and Grossman, M. (1996). Price, tobacco control policies and youth smoking. Working Paper No. 5740. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chaloupka, F.J., and Warner, K.E. (2000). The economics of smoking. In J.P. Newhouse and A. Cuyler (Eds.), Handbook of health economics. New York: Elsevier.

Chaloupka, F.J., and Wechsler, H. (1997). Price, tobacco control policies and smoking among young adults. Journal of Health Economics, 16(3), 359-373.

Cook, P.J., and Moore, M.J., (2002). The economics of alcohol abuse and alcohol-control policies: Price levels, including excise taxes, are effective at controlling alcohol consumption. Health Affairs, 21(2), 120-133.

Cornwall, A., and Jewkes, R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science and Medicine, 41(12), 1667-1676.

Cummings, K.M., Hyland, A., Pechacek, T.F., Orlandi, M., and Lynn, W.R. (1997). Comparison of recent trends in adolescent and adult cigarette smoking behavior and brand preferences. Tobacco Control, 6 (Suppl. 2), S31-S37.

Dee, T.S., and Evans, W.N. (1998). A comment on DeCicca, Kenkel and Mathios. Working Paper, School of Economics, Georgia Institute of Technology.

DiFranza, J.R., Richards, J.W., Paulman, P.M., Wolf-Gillespie, W., Fletcher, C., Jaffe, R.D., and Murray, D. (1991). RJR Nabisco’s cartoon camel promotes Camel cigarettes to children. Journal of the American Medical Association, 266, 3149-3153.

Ellickson, P., and Bell, R. (1990). Drug prevention in junior high school: A multi-site longitudinal test. Science, 247, 1299-1305.

Ennett, S.T., Rosenbaum, D.P., Flewelling, R.L., Bieler, G.S., Ringwalt, C.L., and Bailey, S.L. (1994). Long-term evaluation of drug abuse resistance education. Addictive Behaviors, 19, 113-125.

Farrelly, M.C., and Bray, J.W., and Office on Smoking and Health. (1998). Response to increases in cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups—United States, 1976-1993. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47(29), 605-609.

Farrelly, M.C., Healton, C.H., Davis, K.C., Messeri, P., Hersey, J.C., and Haviland, M. Lyndon. (2002a). Getting to the truth: Evaluating national tobacco counter-marketing campaigns. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 901-907.

Farrelly, M.C., Niederdeppe, J. and Yarsevich, J. (2002b, July). Future directions in tobacco counter-marketing mass media campaigns. Unpublished paper presented at the Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference, Santa Fe, NM.

Feighery, E., Borzekowski, D.L., Schooler, C., and Flora, J. (1998). Seeing, wanting, owning: The relationship between receptivity to tobacco marketing and smoking susceptibility in young people. Tobacco Control, 7, 123-128.

Fichtenberg, C.M., and Glantz, S.A. (2002). Youth access interventions do not affect youth smoking. Pediatrics, 109(6), 1088-1092.

Flay, B.R., Hu, F.B., and Richardson, J. (1998). Psychosocial predictors of different stages of cigarette smoking among high school students. Preventive Medicine, 27, A9-A18.

Florida Department of Health, Office of Tobacco Control. (2000, March 17). Report regarding the progress of the Tobacco Pilot Program. Unpublished, In-house.

Forster, J.L., and Wolfson, M. (1998). Youth access to tobacco: Policies and politics. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 203-235.

Gilpin, E.A., and Pierce, J.P. (1997). Trends in adolescent smoking initiation in the United States: Is tobacco marketing an influence? Tobacco Control, 6(2), 122-127.

Giovino, G.A. (1999). Epidemiology of tobacco use among U.S. adolescents. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 1(Supp. 1), 40-41.

Glantz, S.A. (1996). Editorial: Preventing tobacco use. The youth access trap. American Journal of Public Health, 86(2), 1156-1158.

Glantz, S.A. (1999). Smoke-free restaurant ordinances do not affect restaurant business. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 5(1), vi-ix.

Glantz, S.A., and Charlesworth, A. (1999). Tourism and hotel revenues before and after passage of smoke-free restaurant ordinances. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281(20), 1911-1998.

Hawthorne, G. (1996). The social impact of life education: Estimating drug use prevalence among Victorian primary school students and the statewide effect of the life education programme. Addiction, 91, 1151-1159.

Hill, D. (1999). Why we should tackle adult smoking first. Tobacco Control, 8, 333-335.

Hu, T.W., Sung, H.Y., and Keeler, T.E. (1995). Reducing cigarette consumption in California: Tobacco taxes vs. an anti-smoking media campaign. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 1218-1222.

Hurt, R.D., Croghan, G.A., Beede, S.D., Wolter, T.D., Croghan, I.T., and Patten, C.A. (2000). Nicotine patch therapy in 101 adolescent smokers: Efficacy, withdrawal symptom relief, and carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine levels. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154(1), 31-37.

Independent Evaluation Consortium. (1998). Final report of the independent evaluation of the California Tobacco Control Prevention and Education Program: Wave 1 data, 1996-1997. Rockville, MD: Gallup Organization.

Institute of Medicine. (1994). Growing up tobacco free: Preventing nicotine addiction in children and youth. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Israel, B.A., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A., and Becker, A.B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202.

Jacobson, P.D., Lantz, P.M., Warner, K.E., Wasserman, J., Pollack, H.A., and Ahlstrom, A.K. (2001). Combating teen smoking: Research and policy strategies. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Jacobson, P.D., and Wasserman, J. (1997). Tobacco control laws: Implementation and enforcement. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Johnson, P.B., Boles, S.M., Vaughan, R., and Kleber, H.D. (2000). The co-occurrence of smoking and binge drinking in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 25(5), 779-783.

Johnston, L.D., O’Malley, P.M., and Bachman, J.G. (2001). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2000. Vol. II: College students and adults ages 19-40. NIH Publication No. 01-4925. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Kropp, R. (1998, March 27). Essay against penalizing youth for possession of tobacco products. GASP of Colorado Education Library. Smoking Control Advocacy Resource Network. Available: http://www.gaspforair.org/gedc/gedcyout.htm.

Lantz, P.M. (2002, July). Smoking on the rise among young adults: Implications for research and policy. Unpublished manuscript presented at Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference, Santa Fe, NM.

Lantz, P.M., Jacobson, P.D., Warner, K.E., Wasserman, J., Pollack, H.A., Berson, J., and Ahlstrom, A. (2000, March). Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control, 9, 47-63.

Lewit, E.M., Hyland, A., Kerrebrock, N., and Cummings, K.M. (1997). Price, public policy, and smoking in young people. Tobacco Control, 6(Suppl. 2), S17-24.

Ling, P.M., and Glantz, S.A. (2002). Using tobacco-industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco-control campaigns. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(22), 2983-2989.

Ling, P.M., Landman, A., and Glantz, S.A. (2002). It is time to abandon youth access tobacco programmes. Tobacco Control, 1(1), 3-6.

Lynan, D.R., Milich, R., Zimmerman, R., Novak, S.P., Logan, T.K., Martin, C., Leukefeld, C., and Clayton, R. (1999). Project DARE: No effects at 10-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 490-593.

Mermelstein, R. (2002, July). Innovative approaches to youth tobacco control: Teen smoking cessation. Unpublished manuscript presented at Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference, Santa Fe, NM.

Monitoring the Future website. (2002, August 30). Available: http://monitoringthefuture.org.

Moore, L., Roberts, C., and Tudor-Smith, C. (2001). School smoking policies and smoking prevalence among adolescents: Multilevel analysis of cross-sectional data from Wales. Tobacco Control, 10, 117-123.

Novelli, W.D. (1999). Don’t smoke, buy Marlboro. British Medical Journal, 318, 1296.

Pentz, M.A., Brannon, B.R, Charlin, V.L., Barrett, E.J., MacKinnon, D.P., and Flay, B.R. (1989a). The power of policy: The relationship of smoking policy to adolescent smoking. American Journal of Public Health, 79, 857-862.

Pentz, M.A., MacKinnon, D.P., Dwyer, J.H., Wang, E.Y., Hansen, W.B., Flay, B.R., and Johnson, C.A. (1989b). Longitudinal effects of the Midwestern Prevention Project on regular and experimental smoking in adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 18, 304-321.

Pentz, M.A., MacKinnon, D.P., Flay, B.R., Hansen, W.B., Johnson, C.A., and Dwyer J.H. (1989c). Primary prevention of chronic diseases in adolescence: Effects of the Midwestern Prevention Project on tobacco use. American Journal of Epidemiology, 130, 713-724.

Perry, C.L. (1999). The tobacco industry and underage youth smoking: Tobacco industry documents from the Minnesota litigation. Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153, 935-941.

Perry, C.L., Kelder, S.H., Murray, D.M., and Klepp, K.I. (1992). Community-wide smoking prevention: Long-term outcomes of the Minnesota Heart Health Program and the Class of 1989 study. American Journal of Public Health, 82(9), 1210-1216.

Peterson, A., Kealy, K., Mann, S., Marek, P., and Sarason, I. (2000). Hutchison Smoking Prevention Project: Long-term randomized trial in school-based tobacco use prevention. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 92, 1979-1991.

Pierce, J.P., Gilpin, E.A., and Choi, W.S. (1999). Sharing the blame: Smoking experimentation and future smoking-attributable mortality due to Joe Camel and Marlboro advertising and promotions. Tobacco Control, 8, 37-44.

Pierce, J.P., Gilpin, E.A., Emery, S.L., White, M.W., Rosbrook, B., and Berry, C.C. (1998). Has the California Tobacco Control Program reduced smoking? Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 893-899.

Pinilla, J., Gonzalez, B., Barber, P., and Santana, Y. (2002). Smoking in young adolescents: An approach with multilevel discrete choice models. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 227-232.

Pucci, L.G. and Siegel, M. (1999). Features of sales promotion in cigarette magazine advertisements, 1980-1993: an analysis of youth exposure in the United States. Tobacco Control, 8(1), 29-36.

Richter, L., and Richter, D.M. (2001). Exposure to parental tobacco and alcohol use: Effects on children’s health and development. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(2), 182-203.

Rigotti, N.A., DiFranza, J.R., and Change, Y. (1997). The effect of enforcing tobacco-sales laws on adolescents’ access to tobacco and smoking behavior. New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 1044-1051.

Rohrbach, L.A., Howard-Pitney, B., Unger, J.B., Dent, C.W., Howard, K.A., Cruz, T. B., Ribisl, K. M., Norman, G. J., Fishbein, H., and Johnson, C.A. (2002). Independent evaluation of the California Tobacco Control Program: Relationships between program exposure and outcomes, 1996-1998. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 975-983.

Rust, L. (1999). Tobacco prevention advertising: Lessons from the commercial world. Nicotine and Tobacco Marketing, 1(Suppl.), 1-89.

Saffer, H., and Chaloupka, F. (1999, February). Tobacco advertising: Economic theory and international evidence. Working Paper No. 6958. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Schooler, C., Feighery, E., and Flora, J.A. (1996). Seventh graders’ self-reported exposure to cigarette marketing and its relationship to their smoking behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 1216-2121.

Siegel, M., Carol, J., Jordan, J., Hobart, R., Schoenmarklinn, S., DuMelle, F., and Fisher, P. (1997, September). Preemption in tobacco control: Review of an emerging public health problem. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 858-863.

Smith, T.A., House, R.F., Jr., Croghan, I.T., Gauvin, T.R., Colligan, R.C., and Offord, K.P. (1996). Nicotine patch therapy in adolescent smokers. Pediatrics, 98(4 Pt. 1), 659-667.

Spoth, R.L., Redmond, C., and Shin, C. (2001). Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: Adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 627-642.

Stead, L.F., and Lancaster, R. (2000). A systematic review of interventions for preventing tobacco sales to minors. Tobacco Control, 9(2), 169-176.

Sussman, S. (2002). Effects of sixty-six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tobacco Induced Disease, 1(1), 35-81.

Unger, J.B., Johnson, C.A., and Rohrbach, L.A. (1995). Recognition and liking of tobacco and alcohol advertisements among adolescents: Relationships with susceptibility to substance use. Preventive Medicine, 24(5), 461-466.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1994). Preventing tobacco use among young people: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Wakefield, M., and Chaloupka, F. (2000). Effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control programmes in reducing teenage smoking in the USA. Tobacco Control, 9(2), 177-186.

Wakefield, M.A., Chaloupka, F.J., Kaufman, N.J., Orleans, C.T, Barker, D.C., and Ruel, E. (2000, August). Effect of restrictions on smoking at home, at school, and in public places on teenage smoking: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal, 321, 333-337.

Wakefield, M., and Giovino, G. (2002, July). Teen penalties for tobacco possession, use and purchase: Evidence and issues. Unpublished manuscript presented at Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference, Santa Fe, NM.

Wasserman, J., Manning, W.G., Newhouse, P., and Winkler, J.D. (1991). The effects of excise taxes and regulations on adult and teenage cigarette smoking. Journal of Health Economics, 10, 43-64.

Wechsler, H., Kelley, K., Seibring, M., Kuo, M., and Rigotti, N.A. (2001). College smoking policies and smoking cessation programs: Results of a survey of college health center directors. Journal of American College of Health, 49(5), 1-8.

Wechsler, H., Rigotti, N.A., Gledhill-Hoyt, J., and Lee, H. (1998). Increased levels of cigarette use among college students: A cause for national concern. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1673-1678.

Windle, M., and Windle, R.C. (1999). Adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use: Current findings. Adolescent Medicine State of the Art Reviews, 10(1), 153-163.

Woodhouse, C.D., Sayre, J.J., and Livingood, W.C. (2001). Tobacco policy and the role of law enforcement in prevention: The value of understanding context. Qualitative Health Research, 11, 683-692.