APPENDIX D

Analysis of Problems and Impediments to Cooperation Between the U.S. and Russia on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Ways of their Elimination or Mitigation

Table of Contents

Introduction

Bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation is principally aimed at strengthening the international nuclear nonproliferation regime, as a component of the international collective security system. Further progress in this area depends to a large extent on the results of the bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation.

The international nuclear nonproliferation regime comprises a set of legal, organizational, administrative and technical measures to prevent the diversion or undeclared production of nuclear fissionable materials, or undeclared use of technologies by a non-nuclear state for the purpose of acquiring nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.

The key elements of the international nuclear nonproliferation regime are as follows:

![]() The Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The NPT came into force in 1970 and, due to active involvement of nuclear states, was extended in 1995 for unlimited duration. Having been signed to date by 187 countries, the NPT became virtually a universal document,

The Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The NPT came into force in 1970 and, due to active involvement of nuclear states, was extended in 1995 for unlimited duration. Having been signed to date by 187 countries, the NPT became virtually a universal document,

![]() The nuclear safeguards system of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA),

The nuclear safeguards system of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA),

![]() The nuclear export control system: the Zangger Committee (created in 1971) and the Nuclear Suppliers Group (created in 1975), and

The nuclear export control system: the Zangger Committee (created in 1971) and the Nuclear Suppliers Group (created in 1975), and

![]() The International Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials During Their Use, Storage and Transportation (1987).

The International Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials During Their Use, Storage and Transportation (1987).

There are two major types of nuclear nonproliferation: nuclear nonproliferation in the nuclear-weapon states and that in the non-nuclear-weapon countries. As regards nuclear states, the nuclear nonproliferation issues—and the main subject of the present study—have two dimensions:

-

Commercial peaceful use of their nuclear technologies in non-nuclear countries with no threat of their diversion to military or terrorist purposes (this is an external dimension of nuclear nonproliferation for the nuclear states)

-

Physical protection, control and accounting, including export control, of national fissionable and radioactive materials, relevant equipment and technologies (an internal dimension of nuclear nonproliferation for the nuclear states).

The Project entitled ”Analysis of problems and impediments to cooperation between the U.S. and Russia on nuclear nonproliferation, and ways of their elimination or mitigation“ has been developed within the framework of the Joint U.S.-Russian Academies Committee on nuclear nonproliferation headed by J.P. Holdren (U.S.A.) and Academician N.P. Laverov (Russia). Major General W.F. Burns (U.S. Army, ret.) and R. Gottemoeller lead the Project on the U.S. side, and Academician A.A. Sarkisov on the Russian side. Academician E.N. Avrorin (Russian Federal Nuclear Center VNIITF) and Alternate Member of RAS L.A. Bolshov (IBRAE RAS) are the Project participants on behalf of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS). In addition to RAS representatives, some leading experts in nuclear nonproliferation of the Russian Federation (R.F.) Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Atomic Energy (Minatom R.F.) and Ministry of

Economic Development and Trade participated in the study and development of this report (Attachment 1).

It should be pointed out that all participants of the Project serve as independent experts in nuclear nonproliferation for the purpose of this study. As a consequence, their viewpoints as stated in the report may not necessarily coincide with official positions of their parent ministries or organizations.

One should proceed from the fact that the fundamental positions of the U.S. and Russia on nuclear nonproliferation coincide. The U.S., as well as Russia, possess by far the largest arsenals of nuclear weapons and fully realize the huge potential hazards of nuclear proliferation, fraught with making it more difficult to control the process by international agencies, and with higher chances for countries with totalitarian and unpredictable political systems to acquire “nuclear” status. Realizing the need to ensure their own national security and maintain international stability, Russia and the U.S. are equally interested in keeping and consolidating the world nuclear nonproliferation system.

Despite many positive and encouraging results in the U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation, a variety of problems and impediments have emerged, which reduce significantly the efficiency of joint efforts of both countries focused on the ultimate goal. There are different causes of these impediments to cooperation, which result from political, legal, technical, managerial, bureaucratic, structural, psychological and other issues.

The Project is aimed at identifying and analyzing the existing impediments and complications to the whole complex of the U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation and elaborating joint recommendations to overcome or mitigate them to be forwarded to the Presidents of the U.S. and Russian Academies.

Despite the obvious importance of the problem under consideration, so far it has not been the subject of special analysis and research. Thus, the report is actually one of the first attempts at a systematic examination of such an important problem. The authors fully realize how complex and interrelated the causes of emerging difficulties and impediments to cooperation are, and they are quite aware of the fact that no single remedy will be able to solve these problems.

At the same time it seems quite possible and useful to develop and propose a set of recommendations and considerations as well as specific actions and measures based on a comprehensive analysis of the whole problem to be used by governing bodies as an adequate framework for choosing optimal lines of work and for making decisions.

The first joint working meeting of the Project participants took place in May 2003 in Moscow and addressed the Project goals, contents, milestones and expected results (Attachment 2). It was agreed that in compliance with basic provisions of this document both sides would carry out independent research and draw up their own versions of a joint report on overcoming impediments to the bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation and would submit the documents for discussions at the next working meeting in Vienna (September 2003).

The present report is an interim Russian version of the future joint U.S.-Russian Academies report. It comprises the results of the analysis of the impediments and problems to the U.S.-Russian bilateral cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation based, largely, on relevant programs in which the Russian participants of the Project, as well as their departments and agencies, were and/or are involved.

Based on the results of the U.S. and Russian interim reports and their discussions in Vienna, further research will be carried out in order to develop and release a joint Final Project report tentatively in January 2004.

1. Nuclear Proliferation Threats

It is believed that in the present-day world nuclear weapons serve as deterrents, a sort of the "Sword of Damocles,” that would be an inevitable punishment for a potential aggressor. However, nuclear weapons by their very nature have huge destructive power and the many other deadly effects inherent in weapons of mass destruction. In case of uncontrolled nuclear proliferation there is a potential threat to the established system of maintaining international stability. Therefore, the responsibility of the nuclear-weapon countries (the so-called “Nuclear Club” comprising, among other countries, the U.S. and Russia) for international stability is extremely high.

On a very general level, factors that may encourage a non-nuclear country to acquire a nuclear weapon, are as follows:

-

General status of the collective security system (the UN) and the efficiency of the international safeguards to ensure the security of a given country as regards any potential aggressor. However, this first-priority challenge goes beyond the scope of this study.

-

Fulfillment by Nuclear Club countries of their commitments within the framework of the international nuclear nonproliferation regime concerning, first and foremost, the reduction of their nuclear arsenals to the minimum acceptable and sufficient level. This problem is rooted in the cold war, as a relic of the arms race, when nuclear countries (and first of all, the U.S. and Russia) fabricated and accumulated nuclear weapons in such quantities that their destructive potential was many times over the above level.

Fundamental obligations of the U.S. and Russia on reducing their nuclear arsenals were stated in the Treaty on the Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (START-I, 1991) and in the Treaty on the Reduction of Strategic Offensive Potentials (SOP, ratified by the sides in 2003). Among the U.S.-Russian projects dealing with the problem under consideration, the following ones should be singled out:

Dilution of Russian Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) into Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) and shipping it to the U.S. to fabricate fuel for commercial nuclear reactors (HEU-LEU Agreement of 1993)

Dilution of Russian Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) into Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) and shipping it to the U.S. to fabricate fuel for commercial nuclear reactors (HEU-LEU Agreement of 1993)

-

Dismantlement of decommissioned Russian nuclear-powered submarines and ships (Agreement on Cooperation in the Elimination of Strategic Offensive Arms (SOAE), 1993)

Dismantlement of decommissioned Russian nuclear-powered submarines and ships (Agreement on Cooperation in the Elimination of Strategic Offensive Arms (SOAE), 1993) Conversion of plutonium-production reactors in Russia (U.S.-Russian Plutonium Production Reactor Agreement (PPRA) of 199715)

Conversion of plutonium-production reactors in Russia (U.S.-Russian Plutonium Production Reactor Agreement (PPRA) of 199715) Disposition of surplus weapons-grade plutonium, which is no longer needed for defense purposes in the U.S. and Russia (Agreements of 1998 and 2000)

Disposition of surplus weapons-grade plutonium, which is no longer needed for defense purposes in the U.S. and Russia (Agreements of 1998 and 2000)

-

The present-day technologies of using nuclear power for peaceful purposes (including the nuclear power industry, research reactors, and power reactor facilities of nuclear submarines and surface vessels) have the following peculiarities: most of the associated nuclear fuel cycle stages are potentially vulnerable (to a variable degree) from the viewpoint of nonproliferation of nuclear materials, which could be used to fabricate nuclear weapons. These are:

Uranium enrichment

Uranium enrichment Nuclear fuel fabrication

Nuclear fuel fabrication Power generation

Power generation Interim storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel (SNF) prior to its ultimate disposal or reprocessing

Interim storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel (SNF) prior to its ultimate disposal or reprocessing SNF reprocessing with extraction of power-grade plutonium

SNF reprocessing with extraction of power-grade plutonium Storage of extracted plutonium

Storage of extracted plutonium Shipping of fresh or spent nuclear fuel.

Shipping of fresh or spent nuclear fuel.

So far this vulnerability has been compensated to a considerable extent by the IAEA international safeguards system and by a set of safeguards arrangements and activities at the national and regional levels.

Unfortunately, the current IAEA safeguards are mainly based on inspections, which, in case of a global growth of nuclear power, may become ineffective and excessively expensive. To ensure long-term sustainable development of the world community, nuclear power in the future will have to resolve the problem related to the risk of indirect nuclear proliferation (i.e., due to the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes) by the development and large-scale deployment of advanced and innovative nuclear energy technologies capable of ensuring proliferation resistance by an optimum combination of predominantly intrinsic features (technologies and materials) and extrinsic measures (IAEA safeguards, nuclear material protection, control and accounting, export control). When considering extrinsic measures (i.e., IAEA safeguards), use of permanent instrumental monitoring systems to eliminate unauthorized modifications in reactors or fuel cycle facilities will be, evidently, necessary as well.

In this context the following initiatives and related opportunities deem important:

-

Bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation on advanced nuclear reactors and fuel cycles (Moscow Summit of the U.S. and Russian Presidents in May, 2002), and

-

Multilateral cooperation of the U.S. and Russia within the framework of the international projects initiated by these countries in the year 2000 on the development of advanced “Generation IV” reactors (GIF) and the IAEA project on innovative nuclear reactors and fuel cycles (INPRO), respectively.

2. Scope, Results and Good Practices of the U.S.-Russian Cooperation on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Related Areas

Besides problems and impediments emerging in U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation, useful experience has been gained, and many specific results obtained. Prior to the analysis of problems and impediments to bilateral cooperation, it would be worthwhile to summarize the experience and good practices that could be used in the development of recommendations on overcoming or mitigation of the impediments.

When analyzing the achievements, a consideration of some other bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation projects related to nuclear nonproliferation (e.g., in the area of improving nuclear safety at nuclear power plants (NPPs)) is deemed useful for learning lessons in nuclear nonproliferation projects.

2.1 Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (Nunn-Lugar Program)

An umbrella Agreement on the safe and secure transportation, storage and destruction of weapons and the prevention of weapons proliferation (also known as the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (CTR) Program), signed by the Presidents of the U.S. and Russia in June 1992, provided a framework for implementation of the START I Treaty, initiated large-scale cooperation on this subject, and was especially important for strengthening strategic stability. The initiative focused on Russia and some other former Soviet Union countries, and was initiated on the U.S. side by U.S. Senators Nunn and Lugar; for this reason the Agreement is often called the Nunn-Lugar program.

As an extension of the intergovernmental umbrella Agreement, about twenty executive agreements have been signed covering a wide range of bilateral interactions, such as elimination of strategic offensive arms, safety improvements of nuclear weapons transportation and storage, disposal of chemical weapons stocks, improvement of the nuclear material protection, control and accounting system, construction of a storage facility for surplus weapons-grade fissionable materials, and shutdown of weapons-grade plutonium production reactors.

When summing up the CTR program implementation results over more than 10 years, it could be concluded that the Agreement made and still makes it possible to address successfully in a relatively short time such important challenges as:

-

Ensuring safe shipping to Russia of nuclear ammunition [warheads] from the Ukraine, Byelorussia and Kazakhstan;

-

Upgrading considerably the safety level in storing both nuclear weapons at R.F. Ministry of Defense facilities and nuclear submarine SNF at the Russian Navy facilities;

-

Modernizing the systems of nuclear material protection, control and accounting at more than 25 Russian nuclear facilities;

-

Constructing a storage facility for surplus weapons-grade fissionable materials (Cheliabinsk, commissioning due date for the first phase the beginning of the year 2004);

-

Building power-generating capacities using fossil fuel to replace those of weapons-grade plutonium producing reactors to be shut down in Tomsk-7 and Krasnojarsk-26 (2005-2006).

Both sides have been continuously working to enhance the efficiency of the CTR program implementation. It should be especially stressed that the decision of the U.S. Government on active involvement of Russian subcontractors and wide use of Russian special purpose equipment contributed significantly to accelerating the progress and improving the cost-effectiveness of the CTR program.

The issue of increasing the share of funds allocated by the U.S. Congress to be received by Russia has been gradually taken care of. At the initial stages of cooperation over 50% of the funds were forwarded to reimburse the costs incurred by U.S. subcontractors and for overhead charges for the U.S. program managers. A mechanism of financial audit of the program costs within contracts with enterprises has been agreed upon and is functioning sufficiently well.

In 1992-1993, in the context of the CTR Agreement, supplementary agreements were signed. To date, some of them have been already completed, while others are still under implementation. Special shipping casks for fissionable materials, equipment to mitigate the consequences of emergency situations and related personnel training programs, and protective coatings and sets to reequip railcars and security cars have been supplied to Russia. Both Russian and U.S. specialists designed and began to construct a safe and reliable storage facility for fissionable materials produced in the process of nuclear weapons elimination.

In 1995 the U.S. President stated that 200 tonnes of fissionable materials were to be decommissioned from the U.S. nuclear arsenal and never used in future to fabricate weapons.

At the 41st session of the IAEA General Conference (1997) a statement of the R.F. President was made public that up to 500 tonnes of HEU and 50 tonnes of plutonium released during the nuclear disarmament process would be withdrawn step-by-step from the Russian defense nuclear programs.

In 2000 an Intergovernmental U.S.-Russian Agreement on disposition of surplus weapons-grade plutonium was signed, according to which each of the sides shall convert 34 tonnes of weapons-grade plutonium into mixed oxide uranium-plutonium (MOX) fuel for NPPs.

The weapons elimination process caused the need to solve tasks related to safe and secure storage of nuclear materials, disposition of surplus fissionable materials, and restructuring and conversion of the Russian nuclear weapons industries. Under conditions of a terrorism threat, both sides have agreed to initiate work aimed at ensuring physical protection of all types of radiation sources.

Between 1997 and 2000, within the framework of the U.S.-Russian plutonium production reactors Agreement, specialists of R.F. Minatom performed design work on converting three plutonium production uranium-graphite reactors operating at the Siberian Chemical Combine (SCC) and the Mining Chemical Combine (MCC). The reactors supply the towns of Seversk and Zheleznogorsk with heat and electricity as by-products. However, the chosen reactor conversion strategy has proved rather expensive and technically complicated. Eventually, a decision was made to construct heat and power generating plants using organic fuel in both Seversk and Zheleznogorsk. After the commissioning of these plants the obsolete plutonium production reactors will be shut down for good.

In addition to the CTR and related agreements, some other important bilateral accords have been concluded to strengthen the nuclear nonproliferation regime.

Since 1993, the HEU-LEU Agreement providing for dilution during 20 years of 500 tonnes of Russian HEU into LEU and shipping of the latter to the U.S. to fabricate fuel for commercial nuclear reactors has been successfully implemented. As of 2003 more than 190 tonnes of HEU have been diluted and 5,700 tonnes of LEU shipped to the U.S., which secured power generation at U.S. nuclear power plants amounting up to 10% of the annual electricity production in the U.S. (i.e., about 50% of nuclear electricity). In its turn, Russia received about $3.7 billion of revenues to be spent to upgrade the safety level of the nuclear power industry, “convert nuclear cities”, and conduct research and development work on advanced nuclear reactors and fuel cycles.

During 1998 through 2003 an Agreement on cooperation to realize the "Nuclear Cities Initiative" was in force, focused on the creation of new work for the personnel made redundant from nuclear defense programs (the Agreement expires in September 2003).

2.2. Nuclear Submarine Dismantlement

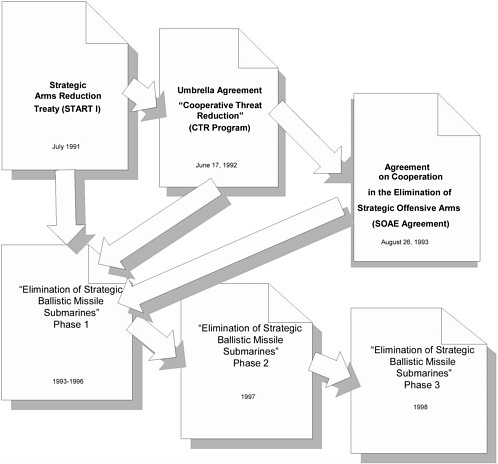

The resolution of the House of Representatives of the U.S. Congress initiated by Senators Nunn and Lugar contained a directive to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) to assist the former Soviet Union countries in the decommissioning of weapons of mass destruction. As a result, on the 26th of August 1993 the U.S. DOD and the R.F. Committee for Defense Industries signed the SOAE Agreement. Due to changes in the R.F. executive authority structure, the Russian commitments related to the Agreement’s implementation were transferred to Rosaviakosmos. Since dismantlement of nuclear submarines decommissioned from the Russian Navy was implemented by R.F. Minatom, an amendment to the SOAE was signed by both R.F. Rosaviakosmos and the U.S. DOD in 2003. The history of the Russian nuclear submarine decommissioning within the framework of the Nunn-Lugar Program is summarized below (Figure 1).

The decommissioning of nuclear submarines is a large-scale political, engineering and environmental problem involving a multitude of facilities and a large complex of interrelated technologies. Among engineering operations related to the decommissioning, those dealing with SNF unloading, storage, transportation and reprocessing (i.e., directly related to nuclear nonproliferation) are the most sophisticated and important.

The start of work on the decommissioning of Russian nuclear submarines coincided with political changes in Russia, accompanied with a severe economic recession. As a consequence, some important decisions were based on specific considerations of the moment and were made under severe financial constraints.

In compliance with the program during 1996-1999 some specialized equipment critical for the program implementation was supplied, including cutting equipment (e.g., an automatic guillotine to cut submarine hulls into sections) and specialized cutting tools, cable reprocessing facilities, and other specialized equipment.

Under the U.S. Government financial support within the program framework a radioactive waste treatment complex was designed and commissioned in October 2000, and a land-based facility for interim storage of SNF unloaded from the decommissioned nuclear submarines was put into operation at the end of 2002.

Under this program the U.S. Government is also funding work on the dismantling of strategic ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). For example, the dismantlement of five "Delta"-class nuclear submarines at the state enterprise “Zvezdochka" was financed in 1998 through 2000.

It is worthy of notice that the U.S. participates only in the dismantling of the SSBNs and, despite appeals from the Russian government, allocates no funds to dismantle Russian multi-purpose nuclear submarines, the number of which substantially exceeds that of the SSBNs. Such considerations are based on the fact that in the latter case the U.S. security is not affected. At the same time the U.S. side has no objections to using the infrastructure built to dismantle the SSBNs for dismantling the multi-purpose submarines.

Figure 1. Phases of the Russian Nuclear Submarine Dismantling Program (within the Nunn-Lugar Program)

2.3. Export Control

Export Control is another important cooperative program between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the R.F. Minatom. This program has been implemented within the framework of both the bilateral U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation and the Protocol of Intent on joint export control activities of 1997 between R.F. Minatom Department of international and external economic cooperation and the U.S. DOE.

Within the program a wide range of subjects has been addressed, which include, but are not limited to:

-

organization of workshops on export control for R.F. Minatom enterprises,

-

development of training documentation for training courses on nuclear export control for Minatom enterprises,

-

development of training documentation for training courses on nuclear export control for the educational system at the R.F. State Customs Committee, and

-

development of appropriate tools to support export control activities (handbooks, databases, glossaries, dictionaries, computer document management and control systems).

In 1997 two R.F. Minatom export control laboratories were established at the State Unitary Enterprise "Physics and Power Institute" (IPPE) and VNIITF. These laboratories perform extensive research for R.F. Minatom, do training and work on export control at the R.F. Minatom enterprises, and review export contracts to identify science-intensive export products.

Within the U.S.-Russian cooperation program these laboratories fulfilled the following tasks:

-

During 1997-2003 the two laboratories held 25 training and methods courses on export control and nuclear nonproliferation related issues (among them, 16 industry-wide and 9 courses for specialists of individual enterprises). About 400 specialists from 135 R.F. Minatom enterprises as well as from other ministries involved in inter-company export control programs at their enterprises attended the industry-wide training courses. In addition, about 450 scientists, engineers and chief executives responsible for export contracts and International Scientific & Technical Center (ISTC) projects took part in the on-site courses.

-

In 1998 specialists of the IPPE laboratory with participation of VNIITF developed the first draft of “The Manual for Nuclear Export Control.” In the course of the following years "The Manual" was regularly revised and supplemented. In 2003 the 6th edition of "The Manual" was issued.

-

Three training courses on nuclear export control were developed jointly with the VNIITF laboratory for basic and advanced training of customs personnel.

The two laboratories also developed:

-

"Nuclear Export Control Desk Reference Book" for R.F. Minatom enterprises (based on "The Manual"),

-

Generic instruction manual on inter-company export control at enterprises,

-

Leaflet for the IPPE export control laboratory on the IPPE web site,

-

English-Russian/Russian-English Glossary and Dictionary-Term Reference Book on export control,

-

"Electronic document management and control concept" to support the R.F. Minatom export control system, and

-

Reference Database on the Internet Information Resources on export control.

This list of activities conducted by the laboratories during 7 years is, obviously, far from being complete.

To ensure transparency of funding and avoid duplication of work performed by the laboratories, working meetings have been held twice a year, which addressed the progress of work within the concluded contracts, their results, the need for work extension, and prospects for further cooperation. Activities that do not have confirmed interest for either of the sides are not considered eligible for funding.

Taking into consideration political aspects of the export control cooperation, the R.F. Minatom is motivated to ensure the involvement of representatives of all R.F. ministries that bear responsibility for the functioning of the export control system in Russia. Such an approach makes it possible to avoid potential bureaucratic impediments to the practical implementation of the cooperation challenges. It is believed that the issues of both export control and nuclear nonproliferation will remain one of most important lines in the U.S.-Russian collaboration in the near future.

2.4. International Nuclear Safety Program

The International Nuclear Safety Program (INSP), though not focused directly on nuclear nonproliferation, is closely related to this subject. It demonstrates a good example of U.S.-Russian cooperation remarkable for its transparency and free access to information on the tasks (including funding) and progress of the whole program, as well as on its specific projects. The INSP program was initiated shortly after the Chernobyl accident and was intended to assist Russia in improving safety of its operating NPPs. By now the program has been largely completed. However, the experience gained appears to be very useful for other areas in the U.S.-Russian cooperation, including nuclear nonproliferation.

Initially information on the progress of the program’s implementation within individual NPP safety improvement areas could be obtained from quarterly and annual reports put together by the U.S. DOE. Later on, as the number of joint projects increased, they were classified by subject, supplied with a detailed description and an identification number to be used when searching for information on an individual project on the INSP web site. Information on project progress was routinely placed in the Internet and, in addition, forwarded in a paper form to NPPs and organizations involved in the project, as well as to R.F. Minatom managers at different levels (from division head to deputy minister) involved in the INSP implementation and the solution of emerging problems.

Project information included description of project goals, due dates (start date and scheduled completion date), obligations of the sides, description of planned activities, names of executive managers from the U.S. DOE and the U.S. company involved in the project, and names of managers from Russian NPPs or enterprises involved into the project with their contact phones and email addresses. This information allowed for easy contact of any project manager in the shortest possible time to resolve the issues.

The funding chart demonstrated not only a total amount allocated for every project in a given fiscal year, but also what had been already spent on the project since its start, as well as an amount needed to complete the project assessed by the project managers. Such transparency made the distribution of funds much easier and allowed for making decisions on funding support of individual projects for the coming fiscal year or vice versa, and for refusal of further funding of some projects in favor of new, more important projects.

The INSP program in Russia, as well as many other cooperative programs, was coordinated by the Joint Coordinating Committee (JCC INSP) comprising managers of the U.S. DOE, the R.F. Minatom, and other principal institutions involved in the program. Routinely, managers of individual INSP projects on both sides discussed the project needs, problems, and progress on their own level. For this reason, successful implementation of INSP projects often depended on mutual relations between the U.S. and Russian managers and on their readiness to make compromises as well. However, all decisions on the funding of INSP projects were made by the JCC INSP.

Twice a year the identification of projects to be funded during the next fiscal year was on the agenda of JCC INSP meetings. For every JCC meeting project managers prepared information on the project’s progress, problems emerging during their implementation that could not be resolved at their managerial level, and justification for additional funding if the relevant project needed money for the next fiscal year. Not only the total amount of funds to be allocated for the next fiscal year was approved at JCC INSP meetings, but also the distribution of funds among individual projects according to established priorities and effective use of already allocated funds.

2.5. Joint Verification Experiment

Cooperation between R.F. Nuclear Centers and U.S. National Laboratories began in the late 1980s. Joint experiments on the verification of nuclear tests was the first large project on this subject. Within the project framework, the U.S.S.R. experts measured a nuclear explosion’s power at the Nevada test site, while the U.S. scientists performed measurements at the Semipalatinsk test site. It should be especially stressed that, when implementing this project, both sides had to overcome many objective and subjective impediments, such as:

-

Need to protect sensitive information concerning fundamental national security issues,

-

Mutual distrust and even suspicion,

-

Different technical solutions of the methods used to perform nuclear tests and measure a nuclear explosion’s power,

-

Necessity for urgent solution of access control issues related to the arrival of large groups of technical experts of the other side, and

-

Examination of sophisticated equipment for installed intelligence devices.

Successfully overcoming these impediments was to a large extent due to thorough analysis of the issues at the U.S.-U.S.S.R. negotiations in Geneva with the participation of diplomats and representatives of leading research institutions of both countries. As a result of the Geneva

negotiations, an inter-governmental agreement addressing all principal problems was drawn up and concluded.

There was another factor, which contributed considerably to the success of these activities: high-level managers empowered to resolve urgent problems headed the teams of both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. experts. Such important joint work brought the experts of both countries closer together. The high professional level of the involved specialists inspired respect and affection that ensured their professional and personal contacts in the following years. The atmosphere developed between the two groups of experts of both countries at the Nevada test site and at the Semipalatinsk test site could be a good example to emulate in cooperation on other subjects. Joint detailed discussions of the experiments’ results were also useful. Thus, the joint verification experiment was a major step toward strengthening confidence between our countries.

2.6. International Scientific and Technology Center

The idea of establishing an International Scientific & Technology Center (ISTC) emerged in the course of the visit of James Baker, the U.S. Secretary of State, to Snezhinsk (VNIITF). The major purpose of the ISTC is to motivate Russian scientists and experts on the weapons of mass destruction to continue their professional activities in Russia and prevent them from leaving to "problem" (rogue) countries. Thus, the ISTC became an appreciable source of support for such scientists in the hardest years of restructuring Russia.

The scope of activities and the number of Russian scientists involved in ISTC projects has no equal. In the last 10 years the ISTC funded projects to the total amount of about $500 million, which involved over 51 thousand scientists at 700 research institutes in Russia, Byelorussia, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Kirghizia.

To a large extent the success of the ISTC activities was due to the fact that the following key issues were agreed at the preliminary stage:

-

Requirements for project proposals and format of their presentation

-

Mechanism of coordination with Russian governmental bodies

-

Project review procedure: expert appraisal at the Scientific Advisory Board and decision-making by the funding parties at the Board of Governors

-

Issues of audit and access to Russian institutions

-

Reimbursement of (exemption from) taxes and customs duties

-

Payment of project grants for their participants

-

Operational support of the ISTC projects by its Executive Directorate.

All participating parties formalized the above arrangements as an international agreement.

2.7. Transparent Dismantlement of Nuclear Warheads

During preparation for a Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START III) and in compliance with the Joint Statement of the U.S. and Russian Presidents (Helsinki, March 1997), multi-purpose studies were carried out at weapons laboratories of the U.S. and Russia in 1996 through 1998

focused on potential approaches, technological and organizational measures, and techniques to ensure transparent dismantlement of nuclear warheads under the conditions of future arms reductions.

The research performed at VNIITF gave an appreciable positive impetus to the better understanding of the issues and of the potential measures capable of enhancing confidence on both sides of the nuclear warheads elimination issues. The following basic proposals were drawn up:

-

a concept of controlled transparent dismantlement of nuclear warheads,

-

technical approaches to confirm authenticity of dismantled warheads and the irreversibility of their elimination,

-

potential scenarios of transparent dismantlement, and

-

experimental control methods.

These activities were mainly performed within contracts between VNIITF and the U.S. national laboratories. The development and demonstration of technologies to be potentially used to ensure transparent dismantlement of nuclear warheads were one of the results of this work:

-

Radiation certification

-

Detection of explosives (because management of explosives necessitates a very careful treatment, instrumental methods were proposed to identify them within the structures to be dismantled)

-

Elimination of nuclear warhead cases

-

Elimination of explosive substance components.

2.8. Nuclear Material Protection, Control and Accounting

Upgrading and improving the system of nuclear materials protection, control and accounting (MPC&A) became one of the most important areas of U.S.-Russian cooperation, both on nuclear nonproliferation and on counteracting unauthorized diversion of nuclear material. Such cooperation made it possible to:

-

Construct new nuclear material storage facilities at R.F. Minatom enterprises and upgrade the available ones,

-

Develop MPC&A related standards and regulations,

-

Develop a federal information system for nuclear material control and accounting,

-

Upgrade instrumentation and methodological support of nuclear material control and accounting,

-

Improve radio communication for ensuring physical protection of facilities with dangerous nuclear material,

-

Improve safety when shipping nuclear materials,

-

Institute departmental security training centers,

-

Equip R.F. Minatom enterprise security units,

-

Establish departmental supervision at R.F. Minatom enterprises,

-

Maintain operability of MPC&A related systems and equipment.

The U.S.-Russian cooperation on this subject involving nuclear facilities of the R.F. Minatom and the R.F. Ministry of Defense (MOD) has been carried out for about 10 years and is characterized by high efficiency and appreciable practical results.

The security level of nuclear materials was considerably improved at more than 25 Minatom facilities involving tens of tons of nuclear materials (including fissionable weapons grade materials). Among such facilities are Federal Nuclear Center “Arzamas-16” (Sarov) and “Cheliabinsk-70” (VNIITF, Snezhinsk), IPPE (Obninsk) and RRC “Kurchatov Institute.”

A long-term plan of joint activities at 10 other Russian nuclear facilities was agreed. During implementation of projects focused on equipping the R.F. MOD facilities with up-to-date physical protection systems the following equipment has been supplied: over 120 units of perimeter protection systems, 400 sets of computer equipment, devices to detect alcohol and drugs in human bodies, and a training complex for the maintenance personnel.

Storage facilities for non-irradiated cores of nuclear submarine reactors equipped with up-to-date MPC&A systems were built for the Arctic and Pacific Navy; storage facilities for both non-irradiated and spent nuclear fuel were equipped with similar systems.

An integrated pilot MPC&A system for the multi-purpose experimental pulse nuclear reactor facility housing tens of kilograms of nuclear weapons-grade materials was developed in 1995 through 2002 at VNIITF in Snezhinsk. For these purposes the U.S. granted an equivalent of $13.1 million as financial and technical support.

These activities were based on the U.S.-Russian CTR Agreement of June 17, 1992; the Protocol of June 15-16, 1999; and the U.S. DOE and R.F. Minatom Protocol of April 25, 2002 addressing the work at VNIITF. According to the latest Protocol, $38 million is to be allocated in 2002-2006 for the continuation and further development of the work.

A special U.S. DOE working group comprising representatives of six U.S. national laboratories served as points of contact with the U.S. labs. The contents of every working stage, labor days, equipment composition and costs were discussed and coordinated at working meetings between the U.S. DOE working group and VNIITF specialists. The working group members controlled the quality of work and the use of funds.

2.9. Inter-Laboratory Cooperation Programs

Relations between Russian Nuclear Centers and the U.S. national labs were not always unclouded. In this context an initiative of S. Hecker, the former Los-Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) Director, to conclude so-called “umbrella” cooperative agreements was of major importance. To date VNIITF has umbrella agreements with LANL, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), and Sandia National Laboratories (SNL).

Such umbrella agreements do not require stipulating general conditions of interactions within every contract as regards specific activities and, thus, facilitate the contract consent processes both at the U.S. DOE and the R.F. Minatom.

Unfortunately, these interactions have been so far mainly a one-way street, because finances have been forwarded to Russia, whereas the scientific information has gone to the U.S. Currently more and more possibilities emerge to establish a balanced cooperation.

3. Impediments to Cooperation Between the U.S. and Russia on Nuclear Nonproliferation

Along with positive results, the multi-year experience of the U.S.-Russian interactions on nuclear nonproliferation revealed a number of "weak points" and impediments hindering further development of the U.S.-Russian collaboration on the subject, some of them a matter of principle. The analysis undertaken in the present research made it possible to classify these problems as follows:

-

High-level political issues

-

Legal issues

-

Scientific and technical cooperation

-

Program management issues

-

ZInteractions at different levels

-

Legacy of the cold war mentality

-

Funding issues

3.1. High-Level Political Issues

3.1.1. Practices of the U.S. Congress to Link the Funding of CTR Projects to Unrelated Political Conditions.

As it is explained by the U.S. side, such linkage results from peculiarities of the U.S. legislation, according to which the U.S. Congress can take yearly funding decisions related to the CTR program implementation only once the U.S. President confirms the fulfillment of the R.F. obligations on international agreements.

As it is known, the lack of convincing evidence that Russia is fulfilling the Chemical Weapons Convention was the pretext to block CTR program funding in 2002. Later on this decision was suspended but only for a limited time.

Quite a similar politically motivated situation is arising regarding the new U.S.-Russian Agreement on the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The U.S. is not willing to take such a step until Russia "freezes" its collaboration with Iran in the nuclear area, which, in the U.S. opinion, could contribute to the build-up of a military nuclear program in that country.

Russia, as it was repeatedly stated, considers the U.S. concerns subjective and unjustified and has given multiple clarifications on this subject. Realizing that the U.S.-Russian cooperative

programs on nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation are of crucial importance for further strengthening of strategic stability and, therefore, meet the vital interests of both countries, linkage of their implementation to any political condition seems counterproductive.

3.1.2. The U.S. Dissatisfaction with the Access Control of U.S. Representatives to Classified Russian Nuclear Sites.

When solving the access-related issues, both sides are guided by their own legislation in force. Despite some restrictions (e.g., a special request notification deadline of 45 days preceding any visit to a Russian classified site), within the U.S.-Russian cooperative programs such access is granted on the basis of yearly-approved lists of the U.S. delegates, which are updated once every six months. Multi-entry visas to Russia for U.S. specialists involved in the R.F. Minatom program implementation are granted by Russia on a limited scale because in most cases such work involves visiting sensitive facilities. To mitigate the entry-visa problem, at present the R.F. Minatom confers double-entry visas to Russia for the U.S. specialists for a period of three months.

At the same time the Russian side fully realizes that in order to attract U.S. private investments (to fund, e.g., the project of “converting” classified nuclear towns in Russia), the issue of access control for the U.S. partners necessitates a more general solution.

It seems that in future a possible solution of the issue could be a removal of concerned production units of the classified facility to be converted from the site’s jurisdiction. The nuclear center "Arzamas-16" (town of Sarov) has had some good experience on this subject related to the joint production with an American company of an artificial kidney machine at the former defense plant "Avangard" (which used to specialize in assembling nuclear warheads).

In its turn, considerable toughening of the U.S. immigration policy after the September 11, 2001 events also resulted in an increasingly complicated procedure of granting the U.S. entry visas to Russian citizens, including specialists involved in the implementation of joint nuclear nonproliferation programs. Having an understanding of the objective reasons for such measures, one has to confess that such a situation cannot help affecting negatively the quality and due dates of program implementation, and needs to be corrected at a high level (i.e., at least at the level of foreign policy departments).

The recently established practice of interviewing Russian citizens at the U.S. Consulate in Moscow prior to granting a U.S. entry visa is also worthy of addressing. Today the U.S. side requires personal attendance at such interviews by every Russian citizen who applies for a U.S. visa. This leads, on the one hand, to additional expenses for interviewees (travel to Moscow, lodging, etc.) and, on the other, results in unnecessary tension due to the unbalanced visa requirements of the sides. Given the arrangement of not interviewing project participants with diplomatic or governmental (business) passports, the U.S. side recently began replacing passports of their specialists with the “right” ones exempting them from the interviews in the Russian Consulate.

It is believed that in this particular case the visa application procedures for both U.S. and Russian specialists could be simplified if they are well-known persons (e.g., included in some pre-agreed lists) involved in the implementation of known (intergovernmental and interdepartmental) projects.

3.1.3. Both the U.S. and Russia are nuclear countries with their own national defense interests, in particular, with their own plans for use of nuclear technologies aimed at ensuring their national security.

Within the CTR cooperative programs it is not a rarity that information on "sensitive" subjects requested by one side cannot be submitted by the other side without affecting its national security interests. Both the requests for such information and the refusals to submit it exert negative effects on maintaining and strengthening confidence between the two partners.

To avoid such situations, it is recommended that (international) requirements (standards) be developed and introduced for nuclear nonproliferation during joint research involving nuclear facilities of nuclear countries sensitive for the countries’ national security. Such requirements could be developed by any two (or more) nuclear countries interested in such cooperation in order to reduce the nuclear proliferation threat. There is no question that these requirements should fully comply with the NPT and international law as a whole, as well as with national legislation, standards, and regulations of the involved countries.

Among other things, such requirements could comprise an agreed classification of nuclear facilities of collaborating countries related to their national security and sensitive to nuclear proliferation, and, therefore, included in the CTR programs. They could also specify comprehensive symmetrical data on such facilities to be submitted by one nuclear country to the other(s) when performing cooperative programs on this subject.

3.1.4. The U.S. and Russia are nuclear countries with their own national economic interests, in particular in the area of commercial peaceful use of nuclear technologies in the non-nuclear countries.

The lack of internationally accepted, explicit, and comprehensive requirements for the non nuclear counties developing peaceful uses of nuclear energy or having plans for their development provides a possibility for the nuclear countries to put forward claims, not always justified, and double (or even triple) standards.

The above reveals the need of ensuring a fair competition for nuclear technologies developed by the nuclear countries, including the U.S. and Russia, in the markets of non-nuclear countries. The competition should proceed in conformity with international rules, which should exclude any possibility for NPT provisions to be used as impediments for penetration of a peaceful nuclear technology developed by a competitor-country into a non-nuclear country.

The economic, scientific, and engineering cooperation program between Russia and Iran to assist Iran in completing and bringing into operation the nuclear power plant in Bushehr is an example of such collaboration. It is joint Russian and Iranian opinion that during program implementation

both sides totally fulfill their international obligations, including those on nuclear nonproliferation. In response to appeals of the international community Iran began consultations with the IAEA on signing the Additional Protocol to the Agreement on the IAEA nuclear safeguards. This Protocol would enlarge considerably the IAEA’s powers to require disclosing undeclared nuclear activities. (Having been signed by 80 countries, the Protocol has already entered into force in 40 countries.)

However, in the U.S. view Iran does not need to develop a national nuclear industry because of abundance of organic fuel resources. In its turn Iran declares that the country is willing to use its natural resources at its own discretion to ensure national (energy) security. For this reason Iran is planning to use natural fossil fuel resources with maximum effectiveness to ensure growth of its national economy by different means, including export sales. The U.S. reproaches Iran for insufficient openness and, in this context, keeps alleging that the Iranian nuclear program may have a military motive. Under the circumstances, when there is no direct evidence to confirm the implementation of a military-oriented nuclear program in Iran, Russia does not share the U.S. opinion.

To avoid such a situation in the future, it is recommended that international requirements for nuclear nonproliferation in commercial use of nuclear technologies supplied by the nuclear countries to the non-nuclear ones be developed and introduced. Two (or more) nuclear countries interested in commercial promotion of their nuclear technologies to the non-nuclear countries could initiate the development of such requirements. The requirements should fully comply with the NPT and comprise explicit information to be submitted by any nuclear country supplying its nuclear technology to a non-nuclear country or to other nuclear country/countries. The development of such requirements could initiate a long-term transition from an international nonproliferation regime based largely on prohibitive measures (which are known to be most often counterproductive) to a nonproliferation regime encouraging the use of nuclear technologies for peaceful purposes in compliance with the established international rules.

When a country that acquired a nuclear weapon after the NPT had been concluded may not be a party to the Treaty (e.g., Israel, India, and Pakistan) or may withdraw from it (North Korea), the NPT’s effectiveness may not live up to expectations. Most likely, an ultimate solution to the nuclear nonproliferation problem may be possible only once possession of nuclear weapons becomes a heavy economic burden outweighing by far the benefits. In other words, instead of closing the entrance doors to the Nuclear Club (which experience tends to demonstrate to be impractical) the admission fee needs to be made exceedingly expensive, therefore rendering the entrance unjustified.

3.1.5. International nuclear nonproliferation requirements for commercial use of nuclear technologies developed by the nuclear countries in the non-nuclear countries, as well as when nuclear states conduct joint studies at facilities sensitive to their national security, could constitute a conceptual foundation for institutionalization of nuclear nonproliferation at a national level.

This can be realized by establishing dedicated high-level nuclear nonproliferation posts to report to the respective Presidents and head a national inter-ministerial Council on nuclear

nonproliferation. The responsibilities of such an official would include coordination of the whole range of issues related to implementation of the U.S.-Russian bilateral projects on nuclear nonproliferation.

It is suggested that a bilateral U.S.-Russian Commission on nuclear nonproliferation be set up to directly coordinate all issues related to implementation of bilateral projects on nuclear nonproliferation, including those of confidentiality and information protection. Based on specific arrangements with agencies involved in the nuclear nonproliferation activities, such a Commission could render administrative and legal support to the organizations in implementing the nonproliferation projects. The Commission could also ensure control over spending of budget funds and submit annual reports to both the U.S. Congress and the R.F. Federal Assembly.

3.2. Legal Issues

As will be seen from the following chapters, the maturity of the legislative basis, the availability of appropriate organizational frameworks and mechanisms to ensure practical application of existing laws, and other legal issues directly affect the implementation of cooperative nuclear nonproliferation programs (as well as those in other areas). The issue is very complicated and of paramount importance, and, therefore, deserves special consideration. Far from pretending to be a comprehensive analysis, an attempt is made to outline specific legal impediments (principally, in the Russian legislation), whose elimination or mitigation would make a significant contribution to further development of U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation.

3.2.1. Taxation

So far within the U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation programs of economic, scientific and technical assistance, “aid” has prevailed, wherein the U.S. Government acts as a "donor," while Russian federal, regional and local executive bodies, legal entities and individuals act as "recipients."

To enhance the efficiency in the implementation of such assistance the Agreements on cooperation in Russia provide different sorts of privileges for both "donors" and "recipients." Among them are: exemption from or refund of the value added tax (VAT), income tax, and other taxes collected by the federal budget when using funds, equipment, labor and other services within the R.F. territory during the execution of cooperative programs.

The issue is most fully addressed in the 1992 CTR Agreement, according to which "…the U.S., their personnel, contractors and contractors' personnel are completely exempted from any taxes and dues of the R.F. and its bodies in relation to activities in line with the Agreement.” Similar privileges have been ensured in case of export from/import to Russia of any equipment, materials, or services necessary for the CTR Agreement implementation. Moreover, the R.F. or its bodies have been taxing neither equipment nor services purchased by the U.S. or on behalf of the U.S. within the R.F. territory, when implementing the CTR Agreement.

It should be emphasized that, thanks to the clearness of the tax exemption clauses in the CTR Agreement, no serious complications related to the exemption from taxation within the

Agreement framework have ever emerged. Even when it expired in 1999, a Protocol to prolong the CTR program for seven years was signed in June 1999, and since then the Agreement has been used in a provisional manner. However, to make the above privileges completely legal, the Protocol needs ratification by the Russian State Duma.

A set of Russian laws regulate interactions of the cooperating sides with the Russian State authorities, among which the following could be singled out:

![]() The 1992 Income tax law concerning enterprises and organizations,

The 1992 Income tax law concerning enterprises and organizations,

![]() The 1992 Tax law concerning the real estate and other property of enterprises, and

The 1992 Tax law concerning the real estate and other property of enterprises, and

![]() The 1999 (May 4) Law on the assistance (aid) to the Russian Federation, amendments and additions to be introduced into specific R.F. legal acts on taxes and privileges on the payments to the state out-of-budget funds in relation to the assistance (aid).

The 1999 (May 4) Law on the assistance (aid) to the Russian Federation, amendments and additions to be introduced into specific R.F. legal acts on taxes and privileges on the payments to the state out-of-budget funds in relation to the assistance (aid).

The complex of the R.F. laws, Government directives, orders of individual Ministries and Agencies, and the U.S.-Russian Agreements on nuclear nonproliferation as a whole seem to constitute a necessary legislative taxation framework during implementation of the cooperative programs.

The taxation situation was much more complicated with other U.S.-Russian Agreements in this area, wherein the issues of tax exemption were regulated by specific directives of the R.F. Government and orders of specific ministries and agencies.

The situation considerably improved after the coming into force of the above Federal Law No_ 95 of May 1999 on assistance (aid) to the Russian Federation, which to a large extent brought order to the taxation and tax exemption processes. Key definitions were introduced by the law, such as the (technical) assistance (aid), which makes related means, goods, and services liable to tax exemption.

In keeping with the R.F. Government Order #1046 of September 17, 1999 the registration of technical aid (assistance) programs is performed by the R.F. Ministry for Economic Development and Trade upon submittal (either by the recipient or the donor) of an application to the Commission on International Technical Assistance set up by the R.F. Government. Prior to making a decision on registration, an expert examination of the submitted documents is to be made by the Commission to verify the compliance of any technical assistance project with the national priorities and principal areas in technical assistance.

However, despite some progress made in the tax exemption area after entering into force of the Federal Law No 95 (1999), a number of problems still persist and need further solution:

![]() Lack of a clear mechanism of the law’s execution in the form of special clauses in the Russian Tax Code. More specifically, Part 2 of the Russian Tax Code, which came into effect in 2000, has no clarification on the tax exemption mechanism regarding the participants in programs of scientific and technical assistance (including the U.S.-Russian cooperative programs). Such a situation results in ambiguous interpretation/execution of the laws as regards the tax exemption/refund mechanism (especially in case of VAT) and,

Lack of a clear mechanism of the law’s execution in the form of special clauses in the Russian Tax Code. More specifically, Part 2 of the Russian Tax Code, which came into effect in 2000, has no clarification on the tax exemption mechanism regarding the participants in programs of scientific and technical assistance (including the U.S.-Russian cooperative programs). Such a situation results in ambiguous interpretation/execution of the laws as regards the tax exemption/refund mechanism (especially in case of VAT) and,

ultimately, slows down the process of the cooperative program implementation. (The experience shows that the VAT paid is reimbursed with substantial delays.)

![]() Long bureaucratic procedures for granting the status of the technical assistance (aid) to such projects due to insufficient "operating capacity" of the Commission.

Long bureaucratic procedures for granting the status of the technical assistance (aid) to such projects due to insufficient "operating capacity" of the Commission.

![]() Lack in the Federal Law of any direct prescription concerning complete exemption from taxes to be paid to the budgets of Russian regions (i.e., administrative subjects). More active involvement of regional authorities in the implementation of the U.S.-Russian cooperative programs on nuclear nonproliferation could be a possible solution of this problem.

Lack in the Federal Law of any direct prescription concerning complete exemption from taxes to be paid to the budgets of Russian regions (i.e., administrative subjects). More active involvement of regional authorities in the implementation of the U.S.-Russian cooperative programs on nuclear nonproliferation could be a possible solution of this problem.

![]() Preservation of the so-called "Single Social Tax" to be paid by individuals—Russian tax residents—involved in bilateral cooperative programs. Cancellation of this tax in relation to a relatively minor group of Russian citizens would cause no harm to the R.F. budget, but could contribute to improving the efficiency of the cooperative efforts.

Preservation of the so-called "Single Social Tax" to be paid by individuals—Russian tax residents—involved in bilateral cooperative programs. Cancellation of this tax in relation to a relatively minor group of Russian citizens would cause no harm to the R.F. budget, but could contribute to improving the efficiency of the cooperative efforts.

At present the Russian State Duma jointly with the Russian Government and related ministries and agencies are looking for ways to improve the Russian legislation on this subject. Several options are being considered, including introduction of amendments to the R.F. Law No 95 of 1999, adoption of a new Federal law preliminarily entitled "On the Order of Use of the foreign assistance for elimination and dismantlement of weapons of mass destruction in the Russian Federation;" and/or introduction of necessary amendments to the R.F. Tax Code.

It seems that, to resolve some of the above problems, the Umbrella Agreement signed by Russia with 10 countries, the EU, and EURATOM in May 2003 on a “Multilateral Nuclear Environment Program in the Russian Federation" (MNEPR) provides a good example. The Agreement has articles regulating the issues of tax exemption (VAT and other taxes regarding the equipment and goods procured in Russia to implement projects/programs within the Agreement framework) and a simplified order of project registration.

3.2.2. Nuclear Liability

The lack of consensus between the U.S. and Russia on formulation of provisions concerning nuclear liability in the bilateral agreements represents a rather serious impediment to further development of cooperation between the two countries in this area. The problem concerns not only new agreements on nuclear nonproliferation, but also prolongation of agreements in force, such as, for example, the "Nuclear Cities Initiative" (expiration date: September 22, 2003) and the "Scientific and technical cooperation in the management of plutonium withdrawn from nuclear defense programs" (expired on July 24, 2003).

The U.S. insists on inclusion in every new Agreement between the U.S. and Russia (and those to be prolonged) of provisions on nuclear liability similar to the relevant article of the 1992 CTR Agreement. According to the CTR Agreement, the U.S. side obtained immunity for its personnel in case of both nuclear and non-nuclear damages. Moreover, in compliance with the CTR Agreement, the responsibility in all cases rests with Russia, including (intended) legal wrong-doing by a foreign citizen.

The Russian side is ready to implement the "liability exemption," but only within the generally recognized standards of international law and, first and foremost, within the framework of the 1963 Vienna Convention on civil liability for nuclear damage (signed by Russia in 1996 and to be ratified by the Russian State Duma).

The exemption from liability for any damage contradicts the Russian civil legislation in force, which provides for reparation of damages by the guilty person(s).

Thus the above U.S. proposal proves unacceptable for Russia because it would commit Russia to exempt the U.S. side from, first, any (not only nuclear) liability, and, second, from the liability for intended damage.

The Russian side has more than once brought the attention of its U.S. partners to the precedents of not providing exemptions from liability in the case of intended actions by U.S. personnel:

![]() An Agreement on the operational safety improvements, measures on risk reduction, and nuclear safety standards for civil nuclear facilities in the Russian Federation» (1993),

An Agreement on the operational safety improvements, measures on risk reduction, and nuclear safety standards for civil nuclear facilities in the Russian Federation» (1993),

![]() The “Nuclear Cities Initiative" (1998),

The “Nuclear Cities Initiative" (1998),

![]() An “Agreement on the scientific and technical cooperation in the management of plutonium withdrawn from the nuclear defense programs" (1998).

An “Agreement on the scientific and technical cooperation in the management of plutonium withdrawn from the nuclear defense programs" (1998).

Another example is the Protocol to the MNEPR Agreement on claims, legal proceedings, and exemption from liability for damaged property, signed in May 2003 by 10 countries (not by the U.S.), the EU and EURATOM. Similar principles had been also put into the 1963 Vienna Convention.

A question may arise why Russia accepted the U.S. wording on liability for damage in the CTR Agreement in 1992, whereas it refuses to do so at present. The reason is that since 1992 important amendments have been introduced into Russian legislation. More specifically, in 1995 the Federal Law on international agreements of the Russian Federation came into effect. In compliance with its provisions, any international agreement between Russia and another country or countries containing clauses that contradict the Russian legislation in force, is to be ratified by the State Duma of the R.F. Federal Assembly.

Because the 1992 CTR Agreement between the U.S. and Russia was signed in compliance with the former Russian legislation, it came into effect immediately on signing without ratification by the State Duma. When the CTR Agreement expired in June 1999 a Protocol was signed to prolong it for 7 years, and today the Agreement is used on a temporary basis. Simultaneously, in compliance with the new Russian legislation in force, a procedure to prepare for ratification of both the CTR Agreement and the Protocol was initiated.

At present the results of considerations of the above documents by the Russian State Duma are difficult to predict because the main provisions of the CTR Agreement Article concerning the civil liability contradict not only the Russian legislation, but also the international legal practices in this area.

As for the prolongation of the U.S.-Russian agreements signed after 1995 and conclusion of new agreements, the Russian sides stands firmly on the need to strictly comply with both the Russian legislation in force and the international legal nuclear liability practices.

Since negotiations on this key subject have virtually reached a deadlock, in order to find a mutually acceptable solution a working meeting between U.S. and Russian experts in the international law would be appropriate in the near future.

The identification and overcoming of the issues related to civil liability for nuclear damage and requiring legislative handling have been a long-standing problem. In recent years these issues have been examined very closely by the Russian State Duma as well as by many governmental and non-governmental entities.

More than once representatives of the donor-countries have placed the issues of "liability for potential nuclear damage" in the forefront and have referred to the 1963 Vienna Convention as one of the fundamental documents in this area, whose ratification by Russia is essential to the implementation of cooperative programs, including those in the nuclear nonproliferation area. Russia signed the Vienna Convention in 1996, but has not yet ratified it. It should be emphasized that among nuclear states only the U.K. and Russia signed it, and none has ratified it. In this context, the importance of ratification of the Vienna Convention by Russia to U.S.-Russian cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation needs further consideration.

3.2.3. Global Partnership Against Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction

The statement made at the June 2002 G8 Summit in Kananaskis, Canada, on establishing the G8 Global Partnership to prevent the spread of weapons and materials of mass destruction (WMD) has been an important step toward reducing the threat of the WMD use. The Global Partnership calls for spending $ 20 billion over the next 10 years (up to 2012) to secure and destroy nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and materials in the former Soviet Union. In its turn, in compliance with the Russian President's statement, Russia has made a firm resolution to assign $ 2 billion for purposes of the Program implementation.

It is expected that the U.S. will cover one half of the above $ 20 billion since the country invests about $ 1 billion every year in nuclear threat reduction activities in Russia and former Soviet Republics. In fact, the continuation of assistance to Russia within the framework of the CTR Agreement will constitute the U.S. contribution to the implementation of the Global Partnership Initiative. Thus, the 1992 CTR Agreement, along with the Protocol on the CTR Agreement Prolongation of June 1999 and some specific intergovernmental and inter-departmental agreements, form the legal basis of U.S.-Russian cooperation within the framework the Global Partnership Initiative.

However, in practice the assistance to Russia for purposes of WMD destruction depends on the solution of a number of issues that must be regulated by the legislature, such as:

![]() Transparency of WMD destruction technologies;

Transparency of WMD destruction technologies;

![]() Guaranteeing the expenditure of allocated funds and equipment as intended;

Guaranteeing the expenditure of allocated funds and equipment as intended;

![]() Taxation of the assistance;

Taxation of the assistance;

![]() Access control of foreign specialists to WMD destruction facilities;

Access control of foreign specialists to WMD destruction facilities;

![]() Holding tenders for the right of performing WMD destruction-related work;

Holding tenders for the right of performing WMD destruction-related work;

![]() Nuclear liability related issues, including the issue of ratifying the Vienna Convention on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage.

Nuclear liability related issues, including the issue of ratifying the Vienna Convention on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage.

The above-mentioned draft legislative act "On the order of use of the foreign assistance for elimination and dismantlement of WMDs in the Russian Federation" might be a solution to ensure the economic, scientific, and technical assistance to Russia is provided in keeping with the uniform long-term rules.

3.3. Scientific and Technical Cooperation

3.3.1. The present-day nuclear power industry based on defense nuclear reactor technologies and related fuel cycles (uranium enrichment for thermal reactors and plutonium extraction from SNF to close the fuel cycle) creates a potential risk of generating weapons-grade nuclear materials. A non-nuclear country importing conventional nuclear power technologies can under specific conditions make an attempt to divert it for military or terrorist purposes.

In case of further expansion of these technologies and facilities in the world the international control over them will be bulky and not quite reliable, whereas the prospects for nuclear disarmament will become doubtful. When thousands of tons of fissionable uranium and plutonium isotopes are circulating in the world's nuclear industry, there will be almost no way of tracing their use. In such a context, technological support of the nonproliferation regime should be put in the forefront: international scientific and engineering programs focused on the development of proliferation-resistant commercial nuclear technologies are needed.

It should be emphasized that, in principle, the nuclear nonproliferation problem cannot be resolved only by technological methods, because there will always be a possibility for illegal use of advanced technologies of uranium enrichment or plutonium extraction from the SNF stored for a long time in cooling ponds or dry storage facilities. Such risks could be only averted by upgrading the present day international, political, and legal nonproliferation regime, including relevant measures of protection, control, and enforcement. The introduction of nuclear technologies not requiring uranium enrichment and/or plutonium extraction, as well as other measures related to the implementation of nuclear nonproliferation, should simplify the control problem.

3.3.2. The lack of a U.S.-Russian agreement on peaceful use of nuclear energy and the presence of the so-called “unresolved intergovernmental political issues” hinder the expansion of joint bilateral research and development on advanced nuclear reactors and fuel cycles resistant to nuclear proliferation.

Such work, which is of crucial importance for both countries, was initiated at the U.S.-Russian Presidents' summit in Moscow in May 2002, where a decision was made on the establishment of a working group to prepare proposals on a joint working program on this subject. At that time the

Presidents' initiative was considered a breakthrough in U.S.-Russian scientific and technical cooperation related to the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

In September 2002 the Ministers of the U.S. DOE and the R.F. Minatom approved the working group report comprising recommendations on further activities in this area. However, so far these activities received no further development because of the "Iranian issue" considered above.

3.3.3. A multi-purpose cooperation—with the participation of the U.S.and Russia—on joint development of proliferation resistant advanced nuclear reactors and fuel cycles is needed. Unfortunately, to date these possibilities still remain unrealized. Taking into account the large and, in our strong belief, mutually beneficial potential of the U.S.-Russian cooperation in the nuclear nonproliferation area, this issue is worthy of a more detailed consideration.