Executive Summary

OVERVIEW

Existing guidelines and regulations for evaluating the safety of conventional food ingredients (e.g., vitamins and minerals) added to infant formulas have worked well in the past; however they are not sufficient to address the diversity of potential new ingredients proposed by manufacturers to develop formulas that mimic the perceived and potential benefits of human milk. Proper nutrition, while important throughout life, is particularly critical during infancy when growth and development are most rapid and when the consequences of inadequate nutrition are most severe. Not all organ systems are fully mature at birth, and many are highly susceptible to environmental inputs as they undergo further development. Thus optimization of nutrition and minimization of exposure to potentially harmful substances in the food supply is of heightened importance during infancy.

Multiple health organizations endorse breastfeeding as the optimal form of nutrition for human infants because of its potential advantages to the infant, including prevention of infectious diseases and its role in neurodevelopment. Despite these recommendations, the vast majority of infants worldwide are fed infant formulas (e.g., liquid or reconstituted powders) at some point in their first year of life, whether as their sole source of nutrition or in combination with human milk, supplemental foods, or both. Infant formulas have been modified over the years to improve flavor, increase shelf life and, recently, to mirror the composition of human milk and the performance of breastfeeding.

Existing guidelines and regulations to assess the safety of ingredients new to infant formulas do not provide a clear and complete set of tools to address the new scientific challenges created by the addition of new ingredients (e.g., probiotics and other complex ingredients). For example, in the United States the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Notification is the most common approach that manufacturers use when they seek to add a new ingredient to infant formula. This process, while scientifically rigorous and transparent, was developed to regulate food ingredients for the general population, not for infants who are a more vulnerable population.

This report, prepared at the request of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada (with potential international utility), addresses the regulatory and research issues that are critical in assessing the safety of the addition of new ingredients to infant formulas.

COMMITTEE CHARGE AND APPROACH

The Committee on the Evaluation of the Addition of Ingredients New to Infant Formula, convened by the Institute of Medicine, was asked to:

-

review methods currently used to assess the safety of ingredients new to infant formulas,

-

identify gaps in current safety assessment guidelines, and

-

identify tools to evaluate the safety of ingredients new to infant formulas under intended conditions of use in term infants.

The committee was asked to focus on ingredients that are regulated under the food provisions of the law and to consider the health and well-being of term infants from birth to 12 months of age. This charge included determining which new ingredients or classes of ingredients are of lesser or greater concern, which additional data would be needed to demonstrate the safety of a component already present in human milk when it is added to the matrix of infant formula, the usefulness of certain safety tools and approaches, and the utilization of preclinical and clinical studies and in-market monitoring. Finally, the committee was asked to apply its recommendations to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs), recently determined GRAS, as a new ingredient in infant formulas and to other ingredients as appropriate.

The committee reviewed U.S., Canadian, and European laws and regulations to examine current processes for manufacturers who wish to add new ingredients to infant formulas: a GRAS Notification and a Food Additive Petition. The committee drew on this review, especially the GRAS Notification process, as it developed its recommendations. The committee also reviewed the special needs of infants and their implications for evaluating the safety of infant formulas.

The committee developed and used algorithms throughout the report to graphically depict the overall process and recommends the use of stepwise decision-tree approaches for the process and for preclinical studies, clinical studies, and in-market surveillance. Each algorithm is a step-by-step decision tree that depicts the logic of a process but does not denote a particular chronology. Algorithms provide a useful tool and a visual way to explain the process of planning the type and depth of safety assessments; to improve data collection, problem solving, and decision making; to incorporate multiple levels of information into a single document; and to utilize a linear approach to identify critical information needed at major decision points. The committee also applied its recommended approaches to LC-PUFAs and to probiotics, recently determined GRAS, to examine the utility of the approaches.

The committee recognizes that some of its recommendations may require statutory changes. Even with this limitation, the committee encourages dialogue among members of government agencies, the public, industry, and academia to act on the recommendations set forth by this report in the best interest of our most vulnerable members of society—our infants.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Approach for Evaluating Safety

Safety evaluation of food ingredients in the United States is based on “reasonable certainty of no harm.” Sections 201(s), 201(z), 409, and 412 of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, associated regulations, and FDA’s Toxicological Principles for the Safety Assessment of Direct Food Additives and Color Additives Used in Food, also known as the Redbook,1 provide guidelines that are used to assess the safety of food ingredients and infant formulas. The Canadian Food and Drugs Regulations, administered by Health Canada, include specific requirements for infant food, novel food, and food ingredients.

In Canada and the United States, the food additive petition processes are similar and require premarket review and approval. In the United States, under the proposed GRAS Notification rule, a manufacturer can declare that a substance is GRAS if there is scientific consensus among qualified experts about its safety under the conditions of intended use. The manufacturer then notifies FDA, and if the agency has no questions, a letter of no objection is issued.

A primary difference between the two routes is that the Food Additive Petition places the responsibility of declaring that a substance is safe and approved under the conditions of use with the regulatory agency, whereas the GRAS Notification process places the responsibility of demonstrating that a substance is GRAS, and therefore safe under the conditions of use, with the manufacturer. The GRAS Notification and Food Additive Petition procedures are intended to ensure the safety (“a reasonable certainty of no harm”; FD&C Act Section 409), not the efficacy, of the proposed ingredient. The vast majority of new ingredients will likely follow the GRAS process to establish safety.

In addition to the regulations, FDA provides preclinical guidelines in its Redbook. This document was prepared to assist in the design of protocols for animal studies conducted to test the safety of food ingredients and includes detailed guidelines for testing the effects of food ingredients on mothers and their developing fetuses. However the special conditions surrounding infancy require distinct procedures to ensure the safety of infant formulas.

The GRAS process is rigorous, flexible, credible, and transparent. However its application does not clearly address possible concerns for the multitude of potential new ingredients in infant formulas. New ingredients may possess a variety of chemical characteristics, nutritional contributions, and pharmacological and physiological activities. Ingredients may be derived from novel sources or processes (e.g., products of fermentation or biotechnology). Such diversity requires safety guidelines that are clear but not overly prescriptive because of the disparity in the issues that each class of ingredient to be added to infant formulas may present. Because of its wide use, the committee used the GRAS Notification process as a starting model in developing its proposed approach for assessing the safety of new ingredients added to infant formulas, without being prescriptive. Some elements of the system proposed by the committee are currently in place.

Infant formula is the only source of nutrition for many infants and, therefore, additional safeguards have been established for infant formulas to which new ingredients are added that are not required for other foods. Regulations under Sections 201(s), 201 (z), and 412 of the FD&C Act have been implemented to ensure the safety of an infant formula to be marketed with a new ingredient. Under these sections of the Act, a proposed rule would

mandate that manufacturers must demonstrate that the formula containing the new ingredient is capable of sustaining physical growth and development over 120 days when formula is likely to be the sole source of infant nutrition. The committee believes that data from growth and development studies should be submitted as part of the material demonstrating safety.

Important Safety Considerations When Regulating Infant Formulas

Most of the principles that govern the safety of ingredients new to infant formulas derive from the same principles that govern food safety for older children and adults. The committee concluded that the six issues listed below must be considered as important safety issues when regulating infant formulas:

-

Infant formulas are the sole or predominant source of nutrition for many infants.

-

Formulas are fed during a sensitive period of development and may therefore have short- and long-term consequences for infant health.

-

Animals may not be the most appropriate model on which to base decisions of safety.

-

“One size fits all” food safety models may not work for all new additions to formulas.

-

Infant formulas could be considered as more than just food (i.e., as a delivery system for non-nutritional agents).

-

Potential benefits, along with safety, should be considered when adding a new ingredient to formulas.

Use of a Hierarchical Approach

Since infants have distinct needs and vulnerabilities, a set of guidelines should be developed to provide a hierarchy of decision-making steps for manufacturers seeking to add new ingredients to infant formulas. Because specific safety assessments will need to be targeted according to the nature of the ingredient, the set of guidelines should allow for flexibility in the approach, while being rigorous and scientifically based.

A hierarchical approach assists in determining the appropriate level of assessment by considering: (1) the harm (e.g., toxicity), and (2) the potential adverse effects of a new ingredient. This hierarchical approach will guide the level of assessments to be applied to the new ingredient by considering the following factors:

-

the reversibility of potential harmful effects,

-

the severity and consequences of adverse effects,

-

the time of onset of manifestations of the adverse effects,

-

the likelihood that a new ingredient could adversely affect a specific system, and

-

whether the effect would be common or rare.

This approach to evaluating the safety of new ingredients to be added to infant formulas was based on the uniqueness and vulnerability of the infant population. Therefore each step in the process requires empirical evidence from many disciplines and the application of the highest standards, whether using methods of bioassay, nutritional analysis, or basic chemistry. This approach is valuable in determining the relative importance of potential adverse effects for each specific new ingredient by providing generic templates for different steps in the safety assessment process rather than specific recommendations for each compound. It is neither realistic nor desirable to design individual templates for each new ingredient; rather,

expert panels can refine the generic templates as needed. This approach is designed for a broad spectrum of ingredients and could be applied to new ingredients to be added to infant formulas regardless of the regulatory process used.

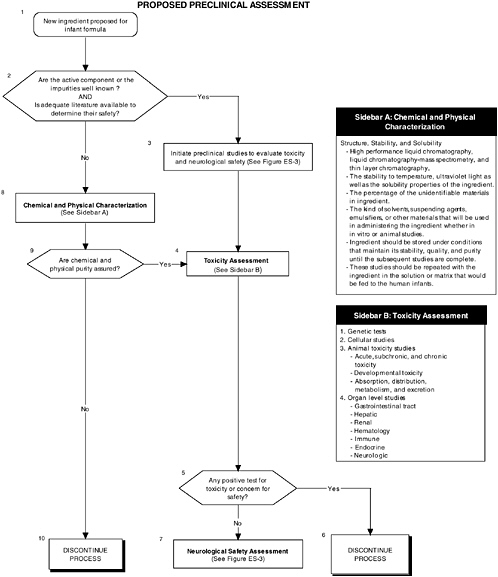

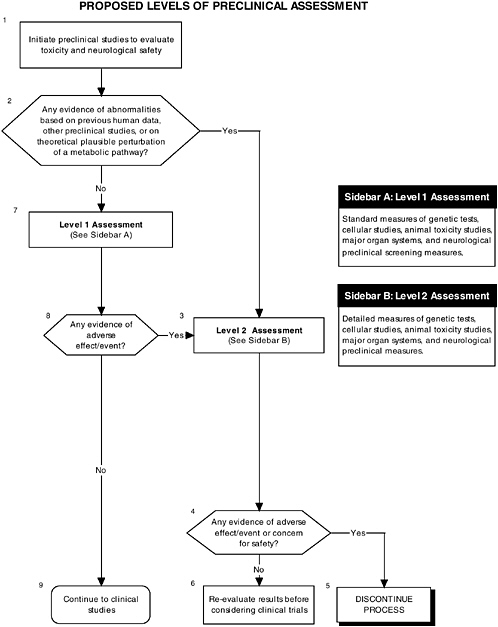

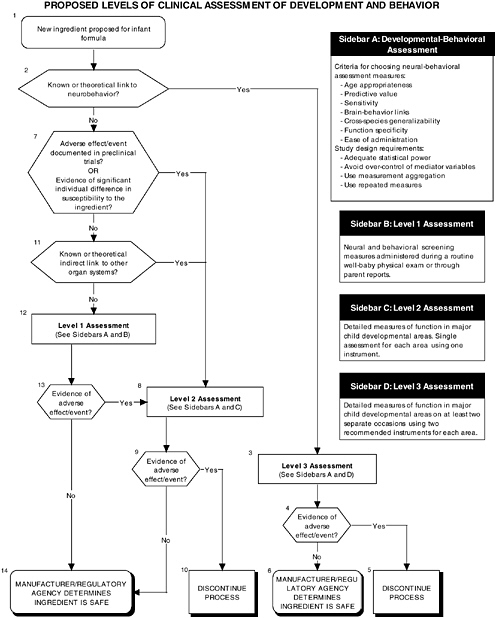

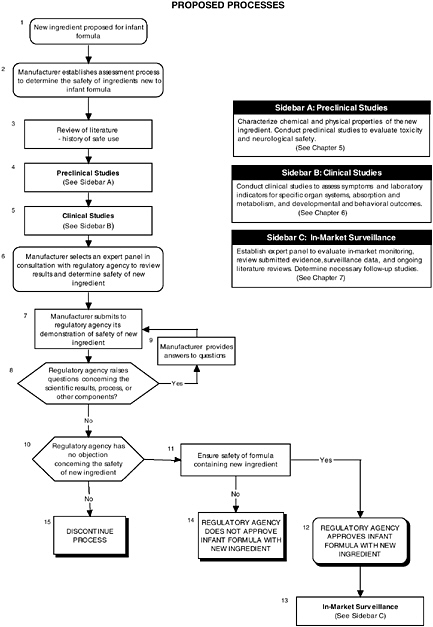

The hierarchical approach is graphically presented by algorithms throughout the report and is applied in Appendix D to LC-PUFAs and probiotics. Each algorithm (see Figures ES-1 through ES-7) is a step-by-step decision tree that depicts the logic of the process but does not denote a particular chronology. For example, a manufacturer may initiate several different studies and procedures at the onset of the process, the results of which could be assessed at different steps in the algorithm. Any new ingredient considered for use in infant formulas must be considered in the context of its form, the matrix, and other ingredients with which it may interact.

Expert Panels

The committee recommends that manufacturers establish balanced, qualified expert panels in consultation with the regulatory agency. The existing GRAS process requires consensus by qualified experts to evaluate the safety of the ingredient under consideration; this consensus is often reached through a panel of scientific experts. The current system does not specify the composition of the panel, and manufacturers may be uncertain about the selection of appropriate panel members.

The panel should have experts that will ask the right questions and form an opinion that is robust and of the highest scientific integrity. The committee strongly recommends that the expert panel include a physician experienced in clinical study assessments, preferably a pediatrician. Guidelines for selecting a panel early in the process could improve the efficiency and objectivity of the process. Each expert panel should be responsible for determining the requisite levels of preclinical and clinical studies and in-market surveillance needed to ensure the safety of new ingredients by utilizing evidence-based approaches and high-quality scientific data.

Additional Elements of a Safety Assessment

Elements of the safety assessments of infant formulas need to be standardized (e.g., toxicity studies, risk assessment). A scientifically rigorous set of guidelines must also allow for flexibility in their approach since specific safety assessments must be targeted according to the nature of the ingredient.

The committee recommends that bioavailability be specifically addressed in any evaluation of the safety of infant formulas. Other factors that should be considered for safety are: tolerance, allergenicity, impact of gastrointestinal flora, and possible nutrient imbalances (if ratios or cofactors are important). While bioavailability is a factor considered under the proposed infant formula regulations, other factors are also of special importance to infants and should be specifically addressed in any evaluation of the safety of infant formulas.

The committee recommends that the manufacturer implement an appropriate in-market surveillance strategy that is based on findings from preclinical and clinical studies and the potential for harm to infants. Infant formula manufacturers routinely conduct passive surveillance (e.g., contact with health care professionals), but guidelines do not exist to assist manufacturers in determining the appropriate type and length of surveillance, from simple methods (e.g., incoming toll-free calls) to rigorous methods (e.g., clinical follow-up of the original study population).

FIGURE ES-1 Proposed process for evaluating the safety of ingredients new to infant formulas algorithm. In-market assessment should be planned in conjunction with preclinical and clinical testing. This algorithm is modeled after the U.S. Generally Recognized as Safe Notification process; similar schemes can be adapted to other regulatory processes. ![]() = a state or condition,

= a state or condition, ![]() = a decision point,

= a decision point, ![]() = an action, sidebar = an elaboration of recommendation or statement.

= an action, sidebar = an elaboration of recommendation or statement.

Preclinical Studies for Evaluating Safety

Preclinical studies are a vital first step to assess the safety and quality of ingredients new to infant formulas. Guidelines and regulations should consider the special needs and vulnerabilities of infants. Also, the diversity in the ingredients and issues requires clear but flexible preclinical guidelines. For example, a complex mixture or ingredients derived from novel sources or processes present unique safety issues. Also, guidelines should provide the most appropriate animal models at relevant developmental stages for testing infant formulas. For example, the most commonly used animal models for general toxicological studies are the rat and mouse, which are of limited use for developmental studies because of the difficulty of feeding formula to a preweanling rodent. The nonhuman primate and the piglet are more amenable for these types of studies because they readily accept infant formula as a nutrient source.

Current guidelines, provided in the FDA Redbook, and regulations do not address the special needs and vulnerabilities of infants or the diversity of potential ingredients.

The committee recommends the use of a two-level assessment approach to determine the potential toxicity of the ingredient, its metabolites, and their effects in the matrix on developing organ systems (see Figure ES-3, Sidebars A and B). Level 1 assessments include standard measures for each organ system (gastrointestinal, blood, kidney, immune, endocrine, and brain). Level 2 assessments include in-depth measures of organ systems that would be used to explicate equivocal level 1 findings or specific theoretical concerns not typically addressed by level 1 tests. Preclinical assessments range from cellular-molecular through whole animal studies (see Figure ES-2, Sidebars A and B).

The committee recommends that a distinct set of procedures that use an appropriate number and type of animal model at relevant developmental stages be included in preclinical studies. At least two animal models should be selected, and justification for the studies, as well as limitations in extrapolating to humans, should be clear, especially regarding the comparative development between the animal model and the human. The appropriate species, age, and safety factors, as well as other factors, such as the timing, bioavailability of the ingredient, and differences in pharmacokinetics and dietary imbalances, should also be considered.

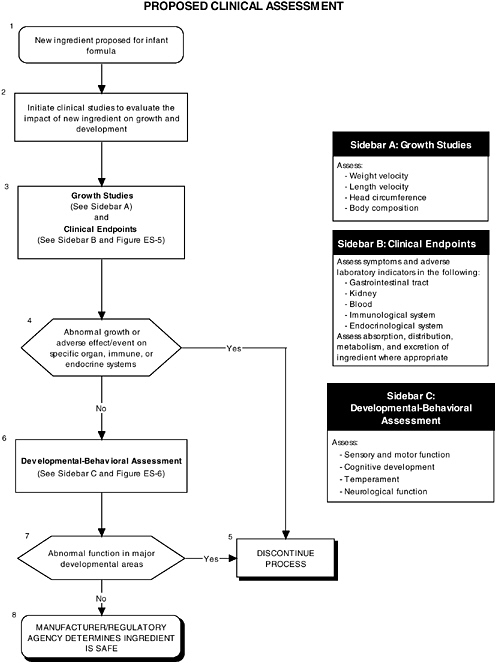

Clinical Tests for Evaluating Safety

Human clinical studies in infants are a vital second step in the safety assessment process after preclinical studies have been satisfactorily completed. Clinical studies can predict how a new infant formula may affect growth and development, organ systems, and developmental-behavioral outcomes. Clinical studies in human infants are needed for several reasons. First, extrapolation from animal studies may be limited by differences between animal and human structure, physiology, and development. Second, extrapolation from isolated tissue studies is limited by the inability of such models to assess functions in the context of whole organ systems where coordination and integration are the rule. Third, there may be no available animal or tissue model to test specific conditions or functions (e.g., tests for allergenicity or higher cognitive functions found only in humans).

There are no explicit requirements for clinical testing of ingredients new to infant formula specified under Canadian or U.S. regulations. However FDA recommends that the studies conform to guidelines presented in section VI.A. of the Redbook. In addition, in the proposed rule under Section 412 of the FD&C Act, FDA proposes that researchers use the 120-day growth study as the main method to assess the ability of an infant formula to sustain normal infant growth.

Growth

The committee recommends that growth studies should continue to be a centerpiece of clinical evaluation of infant formulas and should include precise and reliable measurements of weight and length velocity, and head circumference. Appropriate measures of body composition should also be assessed (see Figure ES-4, Sidebar A). These measures help researchers understand the impact of an ingredient new to infant formulas. For example, weight is responsive to acute insults, such as infectious morbidity or changes in nutrient intakes, and recumbent length is an overall indicator of linear or bone growth.

The committee recommends that clinical growth studies follow the study participants for the entire period when infant formula remains a substantial source of nutrients in the diet of the infant. The committee believes that a 120-day growth study, in the 1996 FDA proposed rule, may be insufficient for several reasons. Currently human milk is recommended as the sole nutrient source for infants ages 4 to 6 months; infant formula, intended as a human milk substitute, is recommended for the same period of time. Ideally formula should be tested for the entire period for which it is intended to be fed as the sole source of infant nutrition (up to 6 months, or roughly 180 days, consistent with breastfeeding guidelines) rather than the currently proposed 120-day period. An additional and more serious limitation of the 120-day growth study is that it does not allow for the determination of delayed effects or for understanding longer-term effects of early perturbations in growth.

The committee recommends the development of specific guidelines that define normal growth and establish a level of difference that represents a safety concern. Specifically, the committee recommends that any addition of an ingredient new to infant formulas should be judged against two controls: the previous iteration of the formula without the added ingredient and human milk. The proposed rule does not define “normal” growth, nor does it identify what represents a biologically meaningful difference among groups of infants consuming different formulas. The committee recognizes that there is very little scientific evidence to establish a level of difference associated with long- or short-term health consequences. However the committee concluded that any systematic and statistically significant difference in size or growth rate among infants fed a formula with the new ingredient versus human milk or an already approved formula should be a safety concern.

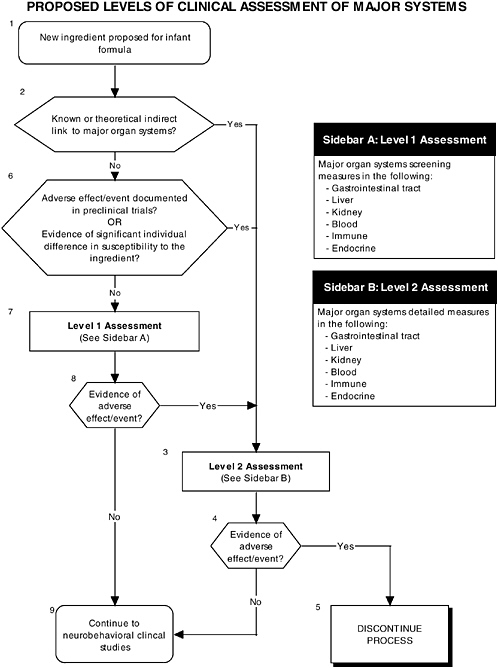

Organ Systems, Neurobiological Development, and Behavior

In addition to growth studies, the committee recommends a two-level assessment approach to assess organ, immunological, and endocrinological systems (see Figure ES-5, Sidebars A and B). Level 1 assessments include standard measures for each organ system (gastrointestinal, blood, kidney, immune, endocrine). Level 2 assessments include in-depth measures of organ systems that would be used to explicate equivocal level 1 findings or specific theoretical concerns not typically addressed by level 1 tests.

These major organ systems must be studied because growth deficits are likely to appear only secondary to effects on specific organs or tissues and may not appear for some time after nutritional insult. For example, slow or inadequate growth is a common denominator of impaired gastrointestinal function, but it does not identify the function that is impaired. In addition, some organ systems (e.g., immune and endocrine) are immature at birth; every effort must be made to ensure that ingredients new to infant formulas will not affect the development of these systems or the expression of their function.

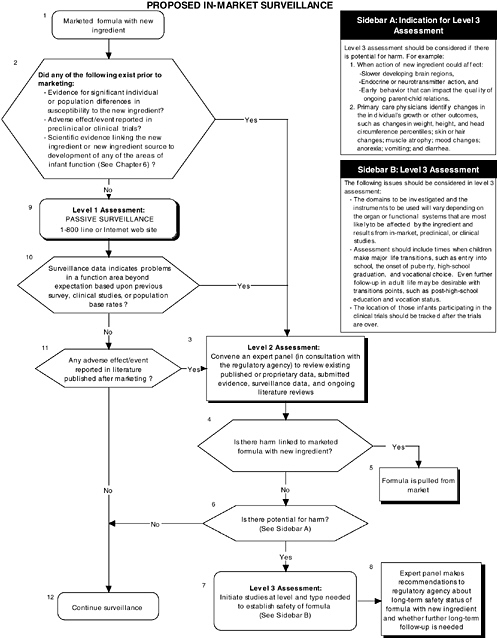

The committee recommends a three-level assessment approach to assess developmental-behavioral outcomes, including sensory-motor, cognitive development, temperament, and

neural functions, with appropriate measurement instruments and study design features (see Figure ES-6, Sidebars B, C, and D). Level 1 assessments include developmental screening measures. Level 2 assessments include in-depth measures of child functions in major developmental areas (single assessment with one instrument). Level 3 assessments include in-depth measures using repeated assessments with multiple instruments.

These developmental-behavioral outcomes are important for the following reasons:

-

Behavioral outcome measures are sensitive to exposure to toxic substances.

-

Developmental-behavioral measures can have long-term predictive value.

-

Bidirectional brain-behavior links exist (e.g., brain development mediates changes in behavioral competence, but the child’s interactions with his or her environment also can influence brain development).

The proper application of developmental-behavioral studies requires the use of the most appropriate measurement instruments and study design features to assess sensory and motor functions, cognitive development, infant temperament, and neurological function.

In-Market Surveillance to Detect Adverse Effects

Although satisfactory completion of the appropriate preclinical and clinical studies diminishes the likelihood of systematic adverse reactions, the risks for adverse reactions cannot be ignored. Adverse effects may not be detected in preclinical studies if the wrong animal model was chosen, if the assessment instrument chosen measured a function other than the one adversely affected by the new ingredient, or if a subpopulation of individuals who are highly sensitive to the new ingredient added to infant formulas was not sufficiently represented in clinical studies. Also, brain areas that are adversely affected by a new ingredient may not become functionally apparent until later in development. Therefore in-market surveillance is needed to ensure safety and normal development of the infant population.

The committee recommends that all submissions seeking to add a new ingredient to infant formula include a systematic plan for continued in-market monitoring and long-term surveillance (see Figure ES-7). Formal regulatory guidelines for in-market surveillance do not exist for infant formulas. Surveillance is generally limited to consumer reporting of adverse events through toll-free numbers or Internet sites established by the manufacturer or the regulatory agency. There are a number of reasons why this approach is inadequate. One reason is the risk of underestimating actual negative occurrences given that not all caregivers will report a problem. Furthermore, caretakers will be less likely to link a child’s problems to earlier intake of infant formula.

The committee, however, recognizes that there are methodological factors (e.g., length of follow-up, confounding factors, lack of statistical power), practical concerns (e.g., continuity of the research team, tracking of subjects, record retention), and cost considerations that limit the implementation of certain in-market surveillance programs.

The committee recommends a three-level assessment approach to determine appropriate in-market surveillance strategies. Level 1 assessments include monitoring the toll-free line or Internet website (passive surveillance). Level 2 assessments include in-market panels to review existing data (both published and proprietary). The same selection and composition recommendations presented earlier also hold with regard to in-market panels. Level 3 assessments include conducting retrospective and/or follow-up studies (active surveillance).

The committee recommends that an expert panel determine the level and strategies to be utilized based on conditions under which potential adverse effects of a new ingredient added

to infant formulas might have been missed in preclinical or clinical trials involving the ingredient.

In-market monitoring information must be assessed for each area of function reviewed, as appropriate. Level 1 assessments are recommended only when all the following conditions occur:

-

There is no evidence of adverse effects in preclinical or clinical studies, including adverse effects with potentially plausible alternative explanations (e.g., the effects are viewed as the result of random chance or the reviewers believe that there may be methodological or statistical problems in the studies).

-

A review of the relevant scientific literature indicates there is no link between the new ingredient, metabolites, secondary effectors, or source and development of any of the areas of infant function previously described.

Level 2 assessments are required when any one of the above conditions does not occur or when level 1 assessments indicate unexpected problems in a function area, based on previous surveys, clinical information, or population-based rates.

In-market follow-up information must be assessed for each area of function reviewed, as appropriate. Level 2 assessments are recommended when any one of the following conditions occurs:

-

A review of the relevant scientific literature indicates that there is existing evidence linking the new ingredient, metabolites, secondary effectors, or source to the growth and development of organ systems that could result in cumulative adverse effects over time.

-

There is evidence of adverse effects in preclinical or clinical studies, including adverse effects with potentially plausible alternative explanations.

-

In-market monitoring reveals any adverse effects reported for the new ingredient, metabolites, secondary effectors, or source.

Level 3 assessments for in-market follow-up are required when any one of the above conditions occurs and level 2 assessments of in-market follow-up (review by the expert panel) indicate potential for harm in a function area.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This report describes the critical need to ensure the safety of infant formulas resulting from a number of converging issues:

-

Infancy is a uniquely vulnerable period of life.

-

Infant formulas are consumed by the vast majority of infants and are the sole source of nutrition for a large segment of infants up to the first 6 months of life.

-

Manufacturers are increasingly interested in adding new ingredients to formulas in an attempt to mimic the perceived and potential benefits of human milk.

-

Existing guidelines and safety regulations lack clarity and completeness in adequately addressing the unique growth and development requirements of infants and the vast diversity of potential new ingredients.

The committee is confident that this report will provide regulatory agencies—FDA, Health Canada, and others—with the recommendations, tools, and resources required to improve guidelines to ensure the safety of infant formulas for generations to come.