7

Schools

Schools are one of the primary locations for reaching the nation’s children and youth. In 2000, 53.2 million students were enrolled in public and private elementary and secondary schools in the United States (U.S. Department of Education, 2002). Many of these schools are also locations for preschool, child-care, and after-school programs in which large numbers of children participate.

The school environment has the potential to affect national obesity prevention efforts both because of the population reach and the amount of time that students spend at school each day. Children obtain about one-third1 of their total daily energy requirement from school lunch (USDA, 2004a), and should expend about 50 percent of their daily energy expenditure while at school, depending on the length of their school day. Given that schools offer numerous and diverse opportunities for young people to learn about energy balance and to make decisions about food and physical activity behaviors, it is critically important that the school environment be structured to promote healthful eating and physical activity behaviors. Further-

more, consistency of the messages and opportunities across the school environment is vital—from the cafeteria, to the playground, to the classroom, to the gymnasium.

Increasingly, schools and school districts across the country are implementing innovative programs focused on improving student nutrition and increasing their physical activity levels. Parents, students, teachers, school administrators, and others play important roles in initiating these changes, and it is important to evaluate these efforts to determine whether they should be expanded, refined, or replaced and whether they should be further disseminated.

It is acknowledged that the school environment is complex, and schools face many economic and time constraints on their ability to address a broad array of student needs. Further, many food- and physical activity-related policies and practices are linked at multiple levels. A change in one practice may impact other areas of the school environment, either related directly to food or physical activity or indirectly to other areas (such as academic, extracurricular, financial, or administrative). The recommended actions, described below, therefore, were developed with the goal of being implemented concurrently and not as stand-alone strategies. Moreover, these actions should reinforce and support each other not only in the schools but in other settings, including the community and home environments (Chapters 6 and 8). Recommendations regarding schools also must acknowledge the diverse ways in which public schools are governed and funded throughout the United States. Although public school governance is primarily local (school boards that oversee school districts), there is variability in the additional role that states play (NRC, 1999).

The recommended actions in this chapter are intended to apply, as relevant, to all the settings where children and youth spend a majority of their organized time outside the home. For most children and youth over the age of 5 years, this will be a school setting (i.e., elementary school, middle school, or high school). For children below the age of 5 years, this may be kindergarten, formal preschool, early childhood education program, child development center, child-care center, or family or other informal child-care setting.

FOOD AND BEVERAGES IN SCHOOLS

The school food environment has undergone a rapid transition from a fairly simple to a highly complex environment, particularly in high schools. Traditionally, school cafeterias offered only the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) federally subsidized school meal, which is required to meet defined nutritional standards. Recently there have been increases, however, in the amount of “à la carte” foods and beverages—items offered individu-

ally and not as part of a school meal—sold in or near the school cafeteria in tandem with the federally reimbursed school meal. Individual foods and beverages are also sold or served in vending machines, at school stores, or at school fundraisers.

Foods and Beverages Sold in Schools

Federal School Meal Programs

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was established in 1946 to “safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other food” (7CFR210.1). Each school day approximately 28 million school-aged children participate in the NSLP and some 8 million participate in the School Breakfast Program (SBP) (USDA, 2003).

Nutrition guidelines for the school meal programs have been revised periodically to maintain consistency with changes in nutritional recommendations. Current regulations for the programs require that the meals be consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and adhere to the RDAs for energy, protein, calcium, iron, vitamin A, and vitamin C. These guidelines are described in Box 7-1.

Several food-based menu-planning approaches are used in the NSLP to ensure that lunches and breakfasts are nutritionally balanced. The majority of schools use the “traditional” food-based menu-planning system, which

|

BOX 7-1 USDA Requirements for School Meal Programs

SOURCES: 7CFR210.10; 7CFR220.8; 7CFR Appendix B to Part 210. |

requires school lunches to offer five food items selected from four food types: fluid milk; meat or meat alternative; at least one serving of bread or grain products; and two or more servings of fruit, vegetables, or both. A second approach is the “nutrient-based” menu-planning approach used by about one-fourth of schools (USDA, 2004c). School food authorities prepare a nutrient analysis of meals for a one-week period to determine whether these meals meet the nutritional requirements outlined by the dietary guidelines (USDA, 2004b). Schools that use this approach must serve milk and offer at least one entrée and one side dish per meal. Requirements for fruit and vegetable servings are not specified under the current guidelines (USDA, 2004b), and it should be noted that high-calorie, energy-dense items (e.g., cookies, cake, and batter-fried foods) can be served to students as part of their school meals.

The target goals for the NSLP and SBP are that no more than 30 percent of calories should come from fat and less than 10 percent of calories from saturated fat (USDA, 2004b). Because milk with high saturated fat content has been a particular concern regarding the students’ dietary intake, schools were required to offer both whole and low-fat milk (currently defined as having 1 percent fat content or less) beginning in 1994 (USDA, 2004b).

In response to research in the early 1990s indicating that school meals were generally not meeting key nutritional goals, USDA launched the School Meals Initiative for Healthy Children in 1995, which provides schools with educational and technical resources for meal planning and preparation (USDA, 2001b). According to data from the second School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study (SNDAS-II), a nationally representative study of the NSLP and SBP conducted in the 1998-1999 school year, lunches in elementary schools provided an average of 33 percent of calories from fat (target goal is 30 percent or less) and 12 percent of calories from saturated fat (target goal is less than 10 percent). The average lunch in secondary schools provided about 35 percent of calories from fat and 12 percent of calories from saturated fat, also failing to meet the targets (USDA, 2001b). However, compared with the first SNDAS survey in the 1991-1992 school year, there were significant increases in the percentages of schools that served meals consistent with the Dietary Guidelines regarding fat and saturated fat content. In the second survey, approximately two-thirds of NSLP menus offered two fruit and vegetable choices, and more than 25 percent included five or more fruit and vegetable choices (USDA, 2001b).

All students are eligible to take advantage of the NSLP and SBP. The 1998-1999 SNDAS-II survey found that approximately 60 percent of students at participating schools did so, either through full-price or reducedcost purchase or by being eligible to receive free meals. Participation was highest in elementary schools (67 percent) and lowest in high schools (39

percent) (USDA, 2001b). Participation was highest among students approved to receive free meals (80 percent) as compared with students receiving reduced-price meals (69 percent) or students paying full price (48 percent).

Only a few studies have compared dietary quality of NSLP participants and nonparticipants. Cullen and colleagues (2000) found that fifth-grade students who selected only the NSLP meal reported consuming up to twice as many servings of fruit, juice, and vegetables than students who ate from the snack bar or brought their lunch from home. In a two-year follow-up study, diets of students as fourth-graders (when they had access to NSLP lunches only) were compared with their diets during the subsequent year, when as fifth-graders they had access to the snack bar in middle school (Cullen and Zakeri, 2004). During that second year the students consumed fewer fruits, fewer nonfried vegetables, less milk, and more sweetened beverages.

Competitive Foods

The term “competitive foods” is used to describe all foods and beverages served or sold in schools that are not part of the federal school meal programs. This includes “à la carte” foods and beverages offered by the school food service; items sold from vending machines located inside or outside the school cafeteria; foods and beverages sold anywhere in the school as part of fundraising efforts by student, faculty, or parent groups; items served in the classroom for snacks and rewards; and foods and beverages made available during after-school activities. As discussed below, competitive foods from these various sources are typically lower in nutritional quality than those offered as part of the school meal programs.

Current federal nutritional guidelines for competitive foods are limited. Foods of “minimal nutritional value”—narrowly defined primarily as soft drinks and certain types of candy (Box 7-1) (7 CFR Appendix B to Part 210)—are prohibited from sale in the school cafeteria while meals are being served. However, no other national standards currently exist to screen competitive foods for nutritional quality within the school setting. Thus items of low nutrient density or high energy density, including cookies, candy bars, potato chips, and other salty or high-fat snack foods, are often allowed for sale in direct competition with the school meals. Furthermore, federal guidelines do not prohibit foods of minimal nutritional value from being sold in vending machines near the cafeteria or at other school locations.

States and school districts, however, may implement their own more-restrictive policies regarding competitive foods, and many states have passed legislation that limits the types of foods allowed for sale in the schools and

the hours during which they are available. A recent report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) found that 21 states had policies that restrict competitive foods beyond USDA regulations (GAO, 2004). For example, California has mandated guidelines for foods and beverages offered in schools. This 2001 legislation includes a provision for funding pilot programs that would, among other things, require fruits and vegetables to be offered for sale in any school location where food or beverages are sold. Additionally, the board of the Los Angeles Unified School District in 2001 voted to implement standards for beverages, which led to a ban on the sale of carbonated beverages on all school campuses (Los Angeles Unified School District, 2004). West Virginia prohibits schools from serving or selling candy bars, foods, or drinks consisting of 40 percent or more added sugar or other sweeteners; juice or juice products containing less than 20 percent real juice; and foods with more than 8 grams of fat per 1-ounce serving. In addition, all soft drinks are prohibited in West Virginia elementary and middle schools (Stuhldreher et al., 1998; Wechsler et al., 2000). Local schools and school districts are also implementing their own restrictions on competitive foods (GAO, 2004). The issues surrounding competitive foods are currently being discussed in many other states and school districts.

Specific policies and nutritional standards are still needed, however, in most school districts. Data from the 2000 School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS) found that only about 40 percent of school districts, but almost no state governments, required schools to offer a choice of two or more fruits or two or more vegetables at lunch time (Wechsler et al., 2001). With the exception of California, the 2000 SHPPS found that no states require schools to offer fruits and vegetables in school stores, snack bars, or vending machines. At the district level, 3.7 percent of school districts require fruits and vegetables to be available in school stores and snack bars, and 1.7 percent require fruits and vegetables to be available in vending machines (Wechsler et al., 2001). A recent statewide survey of Minnesota secondary school principals found that only 32 percent of their schools had policies of any kind about nutrition and food and that 18 percent had policies regarding items sold from school vending machines (French et al., 2002). Seventy-seven percent of these school principals reported having vending machine contracts with soft drink companies.

Competitive foods represent a significant share of the foods that students purchase and consume at school, particularly in high schools (Wechsler et al., 2001). National survey data from the 2000 SHPPS show that competitive foods are widely available in many elementary schools, most middle schools, and almost all secondary schools (Wechsler et al., 2001). In 2000, food and beverage items were sold to students from vending machines, school stores, or snack bars in 98 percent of secondary schools, 74 percent of middle schools, and 43 percent of elementary schools.

Data from a recent study of 20 high schools in Minnesota found a median of 11 vending machines in each school—typically four soft drink machines, five machines dispensing other beverages (e.g., fruit juice, sports drinks, or water), and two snack machines (French et al., 2003).

Available data show that competitive foods are often high in energy density (often high fat or high sugar) and low in nutrient density (Story et al., 1996; Harnack et al., 2000; Wechsler et al., 2001; Zive et al., 2002; French et al., 2003). National data from the SHPPS survey show that 80 percent of the à la carte areas in high schools sell high-fat cookies and baked goods, and 24 percent sell chocolate candy (Wechsler et al., 2001). Although fruits and vegetables are generally available—they are sold in the à la carte areas of 68 percent of elementary schools, 74 percent of middle schools, and 90 percent of secondary schools—energy-dense foods tend to comprise the majority of competitive foods offered for sale. For example, at the 20 Minnesota high schools noted above, chips, cookies, pastry, candy, and ice cream accounted for 51.1 percent of all à la carte foods offered, while fruits and vegetables were at 4.5 percent, and salads 0.2 percent (French et al., 2003).

Because students’ food choices are influenced by the total food environment, the simple availability of healthful foods such as fruits and vegetables may not be sufficient to prompt the choice of these targeted items when other food items of high palatability (often high-fat or high-sugar items) are easily accessible, especially those that are heavily marketed to children and youth. Data from two recent studies conducted in middle schools provide empirical evidence for this hypothesis (Cullen et al., 2000; Kubik et al., 2003). Fruit and vegetable intake was lower among students at schools where à la carte foods were available, in comparison with schools where à la carte foods were not available. Not surprisingly, when given the choice many students select the higher fat and higher sugar items. However, data from a recent randomized trial involving 20 high schools indicate that offering a wider range of healthful foods can be an effective way to promote better food choices among high school students (French et al., 2004). In combination with student-led schoolwide promotions, increases in the availability of healthier à la carte foods led to significant increases in sales of the targeted foods to students over a 2-year period. Taken together, such findings suggest that restricting the availability of high-calorie, energy-dense foods in schools while increasing the availability of healthful foods might be an effective strategy for promoting more healthful food choices among students in schools.

The present reality, however, falls short of this situation. The rapid growth in the availability and marketing of à la carte foods and beverages, of soft drinks and other high-sugar beverages in school vending machines, and of other sources of competitive foods throughout the school environ-

ment has become an important issue. Bearing significantly as it does on student nutrition and obesity prevention efforts, this issue urgently needs attention from leaders at national, state, and local levels. New policies are needed, both to ensure that the foods available at schools are consistent with current nutritional guidelines and to support the goal of preventing excess energy intake among students and helping students achieve energy balance at a healthy weight.

School-Based Dietary Intervention Studies

School-based interventions to improve food choices and dietary quality among students have been designed primarily as multifaceted interventions that include one or more of the following components:

-

Changes in food service and the food environment (e.g., food availability, preparation methods, price)

-

Promotional activities (cafeteria-based or schoolwide)

-

Classroom curricula on nutrition education and behavioral skills

-

Parental involvement (e.g., informational newsletters or parentchild home activities).

Most often these interventions have targeted total fat, saturated fat, or fruit and vegetable intake. In addition, they may have addressed other weight-related behaviors such as physical activity or television viewing (reviewed later in this chapter). This section focuses on the large-scale controlled intervention studies that have examined weight status or body mass index (BMI) changes as an outcome measure. A much larger literature exists on school-based interventions to change the dietary behaviors of students, including the 5-A-Day and Know Your Body studies (Walter et al., 1985; Hearn et al., 1998).

Evaluation of the literature on such interventions is complicated because of their variety and the multicomponent nature of their designs, making comparisons of results difficult. In addition, differences exist across studies in the number and types of food-related behaviors and age groups targeted. Studies based in elementary, middle, and high schools differ not only in the developmental stage of the students, but in the corresponding physical and social environments, which contrast dramatically, for example, in the availability of à la carte foods, fast foods, snack bars, and vending machines. High school students are also more likely than elementary or middle school students to leave campus during the lunch period. These variables may moderate the effects of interventions designed to influence food choices in the school setting.

The Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH), the largest and most comprehensive school-based intervention yet undertaken, targeted diet and physical activity behaviors as secondary outcome variables (Box 7-2). This randomized trial involving 96 elementary schools did not result in significant changes in body weight; however, significant changes did occur in the school food environment and in reported dietary intakes by students (Luepker et al., 1996). Compared to control schools, the fat content of meals at the intervention school meals was substantially lowered, and intervention students’ reported dietary fat intake was significantly reduced relative to that of control students. Also, as noted below in the discussion on physical activity, the percentage of physical education classroom time with moderate to vigorous physical activity increased in the intervention schools. The researchers speculated that the reasons for the lack of changes in physiologic risk factors may be related to the growth and development stage of the students or to the relatively low magnitude of the changes in food intake and physical activity levels (Luepker et al., 1996).

Pathways, a large, multicomponent school-based intervention designed as an obesity prevention study, was conducted among third- to fifth-grade American-Indian children in reservation schools over a 3-year period (Caballero et al., 1998). Pathways did not significantly affect body-weight change, but significant intervention-related changes were observed for some dietary and physical activity behaviors, including lower fat intake and higher self-reported physical activity levels in the students in the intervention schools (Caballero et al., 2003). The goal of the food service intervention—to reduce the fat content of the school meals—was achieved. Both the CATCH and Pathways interventions show the feasibility of making positive changes in the school food environment, but also the challenges still to be faced in designing primary obesity prevention interventions in schools. As pointed out by the researchers in the Pathways study, restriction of energy intake is not an option in schools because there are students who are below the fifth BMI percentile, additionally, the school meals programs have to meet minimum mandatory levels for calorie content (Caballero et al., 2003).

Several other school-based intervention studies have shown significant effects on body-weight outcomes; these studies tested multicomponent interventions not limited only to targeting dietary change. Planet Health reported reductions in the prevalence of obesity among girls only (Gortmaker et al., 1999), and the Stanford Adolescent Heart Health Program observed reductions in BMI, triceps skinfold thickness, and subscapular skinfold thickness among boys and girls (Killen et al., 1988).

Overall, school-based interventions, both multicomponent and single component, have produced healthful food choices among students. Envi-

|

BOX 7-2 Selected School-Based Interventions Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH)—Designed as a health behavior intervention for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, CATCH was evaluated in a randomized field trial in 96 elementary schools in California, Louisiana, Minnesota, and Texas (Luepker et al., 1996).CATCH schools received school food service modifications and food service personnel training, physical education (PE) interventions and teacher training, and classroom curricula that addressed eating behaviors, physical activity, and smoking (Luepker et al., 1996). The primary individual outcome examined was change in serum cholesterol concentration; school-based outcomes were also examined. Pathways—Designed to reduce obesity in American-Indian children in grades three through five, a randomized trial was conducted in 41 schools serving American-Indian communities in Arizona, New Mexico, and South Dakota (Caballero et al., 1998; Davis et al., 1999). This multicomponent program involved incorporation of high-energy activities in PE classes and recess; food service training and nutritional educational materials; classroom curricula enhancements; and family efforts including family fun nights, take-home action- and snack-packs, and family advisory councils. The primary outcome measure was the mean difference between intervention and control schools in percentage of body fat at the end of the fifth grade. Planet Health—A curriculum-based health intervention, Planet Health lessons were integrated into the math, language arts, social studies, science, and PE curricula of grades six through eight. The lessons focus on teaching better dietary |

ronmental interventions, which target reduced consumption of high-fat foods and greater intake of fruits and vegetables through variations in availability, pricing, and promotion in the school environment (Whitaker et al., 1993, 1994; Luepker et al., 1996; Caballero et al., 1998; Perry et al., 1998, 2004; Reynolds et al., 2000; French et al., 2001, 2004; French and Stables, 2003) may have a particularly significant independent effect on food choices (French et al., 2001; French and Stables, 2003). But their impacts are perhaps smaller in magnitude than when deployed as part of a multicomponent intervention program (Perry et al., 1998, 2004; French et al., 2001; French and Stables, 2003).

Because classroom education/behavioral skills curricula, for example, have typically been embedded in a multicomponent program, the effectiveness of this intervention component is difficult to evaluate as an isolated strategy. Furthermore, caution is needed in interpreting studies of self-reports of dietary intakes, which may be subject to reporting errors and bias.

|

habits, promoting physical activity, and reducing television viewing (Gortmaker et al., 1999). Evaluation of the intervention involved comparing obesity prevalence and behavioral changes among students in five intervention and five control schools in the Boston area. Sports, Play and Active Recreation for Kids (SPARK)—A school-based intervention designed to improve the quantity and quality of physical education, the evaluation involved seven elementary schools in southern California in a 3-year study (McKenzie et al., 1997). The SPARK program involves enhancements to the PE curriculum, implementation of a self-management curriculum, and teacher inservice training programs. Outcomes assessed included changes in student BMI and physical activity levels. Stanford Adolescent Heart Health Program—Designed to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors in high school students, the intervention consisted of 20 50-minute classroom sessions on physical activity, nutrition, smoking, and stress (Killen et al., 1988). The evaluation of the intervention compared the results of 10th-grade students in four high schools in northern California on behavioral changes and physiological variables including BMI. Stanford S.M.A.R.T. (Student Media Awareness to Reduce Television)—Designed to motivate children to reduce their television watching and video game usage, the intervention was evaluated in two elementary schools in California (Robinson, 1999). Students in the intervention third- and fourth-grade classrooms participated in an 18-lesson, six-month curriculum and families could use an electronic television time manager. The primary outcome measure was BMI; other physiologic variables and behavioral changes were also assessed. |

Recent and Ongoing Pilot Program

Several pilot programs have been developed at the school, district, state, and federal levels to explore strategies to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among students in school. The committee is not aware of any published outcome evaluation of these studies but the programs are described here to illustrate current approaches that may warrant continued funding and more systematic analysis. The most recent and perhaps largest effort to increase the availability and consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables was implemented by USDA during the 2002-2003 school year (Buzby et al., 2003). One hundred schools in four states (Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Ohio) and seven schools in New Mexico’s Zuni Indian Tribal Organization participated in the pilot program, which distributed fruit and vegetables free to participating schools. Schools could choose when and how to distribute the produce to students. The program requested, however, that the fruits and vegetables be made available to students outside the regular school meal periods. Due to limited funding, no

quantitative data were collected on the effects of the program on students’ fruit and vegetable consumption or on any other dietary outcomes. However, schools and school food-service staff reported that the program was positively received (Buzby et al., 2003), and there are plans to expand the program. A similar program was developed and pilot-tested on a national basis in the United Kingdom beginning in 2000. As far as the committee is aware, no quantitative evaluation data are available (United Kingdom Department of Health, 2002).

The Department of Defense’s Fresh Produce Program has been working with schools in several states to provide fresh produce for the school meal programs. Schools have also begun to incorporate produce from school gardens (Morris and Zidenberg-Cherr, 2002; Stone, 2002), school salad bars (USDA, 2002), and farmers’ markets (Misako and Fisher, 2002) into the school meal program in an effort to increase student participation and specifically to increase their fruit and vegetable consumption (Box 7-3). Evaluation of these and other similar programs is important in determining the effects of these changes on student dietary behaviors.

Next Steps

As discussed above, several large-scale school-based intervention studies demonstrate that changes in the school food environment can impact students’ dietary choices and improve the nutrient quality of their diets while at school.

Schools, school districts, and state educational agencies need to ensure that all meals served or sold in schools are in compliance with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Additionally, schools should focus on improving

|

BOX 7-3 Edible Schoolyard The Edible Schoolyard is a nonprofit program conducted at the Martin Luther King Junior Middle School in Berkeley, California, a public school for sixth- through eighth-graders. Students participate in all phases of the Seed to Table approach—planting vegetables, grains, and fruits; tending and harvesting the crops; preparing meals with the produce they have grown; and recycling the vegetable scraps back to the garden. This cooking and gardening program involves classroom lessons and hands-on experience in the garden and in the kitchen. The program’s goals include an enhanced understanding of the cycle of food production; the focus of evaluation efforts to date has been on ecoliteracy. SOURCE: Edible Schoolyard, 2004. |

food quality in the school meal programs. Increasing the availability of whole-grain foods, low-fat milk, and fresh local produce will not only be more healthful for participating students, but has the potential to attract greater participation.

Current nutritional standards are extremely limited for regulating competitive foods sold in schools, and many schools are selling high-calorie, energy-dense food and beverage items, often in competition with school meal programs. To ensure that foods and beverages sold or served to students in school are healthful, USDA, with independent scientific advice, should establish nutritional standards for all food and beverage items served or sold in schools. Such standards need to be applied to all meals and all foods and beverages served or sold within the school environment.2 Among the many nutritional issues, consideration should be given to setting standards for the fat and sugar content of school foods, because they are often high in calories and in energy density. State education agencies and local school boards should adopt and implement these standards or develop stricter standards for their local schools. Without such schoolwide standards, different sources compete for student sales under unequal conditions. Such competitive practices often give unfair advantage to those selling less healthful food and beverage items to students. Providing and enforcing uniform standards for meals, foods, and beverages on a school-wide basis also establishes a social norm for healthful eating behaviors. The standards ensure that the school environment is one in which healthful eating is promoted and modeled, consistent with nutrition education messages taught in the classroom.

It is important that evaluations be conducted to assess the impact of changes on competitive foods’ nutritional value and availability, on student dietary quality, and on revenues generated by food and beverage sales. Evaluations of the school food environment may benefit from point-of-service purchase information available from automated systems in school cafeterias. Additionally, evaluations of the efficacy and effectiveness of school-based multicomponent interventions are needed to determine whether these programs should be continued, replicated, expanded, or replaced.

In efforts to make changes in school foods, the school food industry should be an important partner in developing innovative approaches to preparing and serving healthful foods and beverages. Training of school

nutrition and food-service personnel should include a focus on obesity prevention efforts. Furthermore, as schools are built or renovated, school districts should take into consideration plans for school kitchens that have adequate preparation and serving space as well as plans for school cafeterias that are of adequate size and layout so that students will not be rushed, uncomfortable, or scheduled to eat lunch too early or too late in the school day.

Funding and Sales of School Meals and Competitive Foods

School Meal Funding

School nutrition programs are financially self-supporting and must generate sufficient revenues to pay for food-service staff, food purchases, and equipment. Schools that participate in the NSLP receive a fixed amount of reimbursement for each school meal served. Federal reimbursement rates are typically 9 to 10 times higher for free meals than for reduced-price or paid meals (FNS/USDA, 2003). Although some states contribute a supplemental amount and most schools also receive donated commodity foods through USDA, federal reimbursements at their present levels are insufficient to cover the remainder of the meals’ actual costs.

To generate funds needed to function, school food services often sell additional foods and beverages that are not part of the school meals program (GAO, 2003). As noted earlier, these items are called “competitive foods” because they compete with the meal programs for students’ spending on foods and beverages while in school. Thus, the federal funding structure places a school food service in the paradoxical situation of competing with itself as well as with other sources that sell food or beverages in school—such as student groups or the school administration (through vending machine contracts)—for student patronage.

In fact, the nationwide SNDAS-II school survey found that sales of à la carte items were inversely related to sales of NSLP meals (USDA, 2001b). Not surprisingly, states that restricted competitive food sales, such as Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, had school meal program participation rates that were higher than the national average (USDA, 2001a).

Full funding for the school meal programs could relieve the pressure on schools’ food services to generate extra funding through the sales of competitive foods. Such a policy may enhance food services by focusing on providing high-quality nutritious meals to encourage maximum participation and may also help alleviate any perceptions among students that only low-income individuals eat the school meals.

Sales of Competitive Foods

Local schools and school education agencies should consider examining policies and practices on the sale of competitive foods and beverages, including those sold in vending machines and as fundraisers. As discussed above, these foods and beverages are often calorie-laden and low in nutrient density. If nutritional standards are developed and implemented for competitive foods and beverages, as recommended in this report, the standards would apply to all food and beverage items sold in the schools, including those sold through vending machines and in fundraising. As seen in states and districts that have already implemented nutritional standards, the result of these standards and policies is that soft drinks and energydense foods are often precluded from being sold. The goal is, of course, a “win-win” situation where sales of healthful foods and beverages in vending machines and other venues would be more healthful for students as well as profitable to schools and school groups.

Current policies vary widely between schools and school districts about how funds are used from the different types of food and beverage sales. Vending machine revenues are often used by school administrators for discretionary budget purposes (Wechsler et al., 2000); examples include purchases of computers, sports equipment, and funding of other school programs and activities that are not funded in the school budget (Nestle, 2000). One of the issues that has been raised is the exclusivity of some schools’ marketing contracts with specific soft drink companies that may include financial and in-kind incentives for the volume of beverages sold (Nestle, 2000; Wechsler et al., 2000).

Food and beverage sales have been used at special events to generate funds needed by student groups, school administrators, and booster clubs to support worthwhile activities such as field trips or the acquisition of uniforms, equipment, or other supplies that are not covered by existing budgets. Schools and school districts should consider adopting policies to discourage the sale of foods and beverages and instead encourage other types of fundraising activities, such as walkathons or fun runs.

Pricing strategies may also be an effective means of promoting the sales of healthful foods, while discouraging sales of high-fat or energy-dense foods and beverages. In an initial pilot study, purchase of fresh fruit and vegetables from à la carte areas in two high schools increased two- to four-fold when prices were reduced by 50 percent (French et al., 1997). In a second study over a 2-year period at 12 high schools and 12 worksites, purchases of more healthful vending machine snacks successively increased when prices of lower fat foods were reduced by 10 percent, 25 percent, and 50 percent compared to prices of the higher fat snacks that were also available (French et al., 2001). Importantly, no significant reduction in

vending machine profits were observed during the price reduction intervention. More generally, reducing the prices of targeted foods has consistently produced increases in their purchase among adolescents in school settings, regardless of whether the target foods were vending machine snacks or fresh fruits and vegetables sold in food-service areas.

These pilot studies point to the need for further research and evaluation of pricing strategies. If competitive food sales to students continue, school food services should consider the strategy of price increases on higher fat, low-nutrient-dense foods in tandem with lower prices on more healthful foods (Hannan et al., 2002). This strategy could achieve the dual goals of promoting healthful food choices among students and maintaining needed school food-service revenues.

Next Steps

Innovative approaches are needed to encourage students to consume nutritious foods and beverages. Pilot programs offer the potential to implement and carefully evaluate a variety of strategies related to pricing and funding issues.

The committee proposes that USDA conduct pilot studies to examine the benefits and costs of providing full funding for school breakfast, lunch, and snack programs in a targeted subset of schools that include a large percentage of children at high risk for obesity. Outcomes to be examined would include the impact on student nutritional status and on obesity prevalence. It may also be valuable to examine whether the cost of providing free meals is less expensive than the cost to monitor and track free and reduced-price eligibility for school meals.

Pilot programs could also be used to develop, implement, and evaluate alternative models to financially support school and student programs without relying significantly on food and beverage sales.

Experimental research is needed to examine the effects of school-based interventions and policy changes on students’ dietary intake and eating behaviors. For example, changes in food availability and access to both healthful and less healthful foods, pricing of foods and beverages sold through competitive food sources and pricing of the school meals, promotional programs to support healthful food choices, and corporate-sponsored in-school food and beverage marketing activities need to be evaluated to determine their effects on students’ diet and eating behaviors. Experimental and quasi-experimental studies are needed to evaluate the effects of school- and district-level policies regarding school food and beverage availability and marketing on student dietary intake and on school revenues. Academic performance and classroom and social behavior are secondary outcomes of interest.

It is important to note that research should also focus on food service at child-care centers, preschools, and other sites that serve meals to young children. More needs to be known about improving nutrition for young children.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

At a time when many children and youth need to increase their physical activity levels, schools offer the environment, the facilities, and the teachers not only for meeting students’ current physical activity needs, but for helping them form the lifelong habits of incorporating physical activity into their daily lives. As discussed in Chapter 3, current recommendations are for children to accumulate a minimum of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each day (Biddle et al., 1998; USDA and DHHS, 2000; Cavill et al., 2001; IOM, 2002; NASPE, 2004). Because children spend over half of their day in school, the committee felt it reasonable to recommend that at least 30 minutes, or half of the recommended daily physical activity time, be accrued during the school day. In addition to its contribution to preventing obesity, regular physical activity has numerous ancillary health and well-being benefits (Chapter 3).

Researchers are examining the extent and nature of the relationship between increased physical activity and enhanced academic performance, but the results to date are inconclusive. In a study involving 7,961 Australian children, Dwyer and colleagues (2001) found that higher academic performance was positively associated with physical fitness and physical activity. Other cross-sectional studies and a few limited longitudinal studies have found similar results, although correlations are often weak (reviewed by Shephard, 1997). Explanations for a positive association include improved motor development, increased self-esteem, and improved behavior due to physical activity; however, there are numerous confounders, including genetic factors, family environment, and changes in teacher and student attitudes.

Physical Education Classes and Recess During School Hours

Daily physical education (PE) for all students is a goal supported by several national health- and education-related organizations, including the National Association for Sport and Physical Education, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (CDC, 1997; AAP, 2000; DHHS, 2000; NASPE, 2004). But although more than three-fourths of the states and school districts responding to the SHPPS survey required that PE be taught, the nature and duration of the classes varied widely in practice (Burgeson et al., 2001) and the percentages requir-

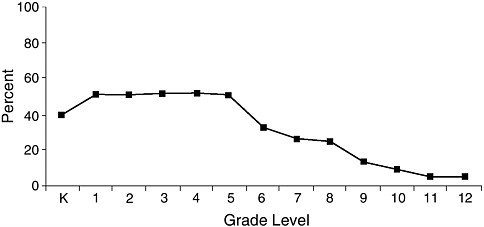

FIGURE 7-1 Percentage of schools that require physical education, by grade. SHPPS 2000.

SOURCE: Burgeson et al., 2001.

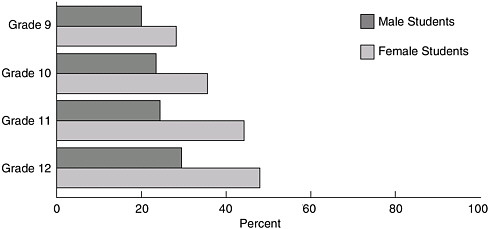

ing PE for all students were low. Only 8.0 percent of elementary schools, 6.4 percent of middle/junior high schools and 5.8 percent of senior high schools provided daily PE3 for the entire school year for all of the students in each grade. Higher percentages of schools (though generally less than one-third) provided PE three days a week or for part of the school year for all students (Burgeson et al., 2001), but for the grades after elementary school the percentages steadily decreased (Figure 7-1 and Figure 7-2).

There have also been concerns about the nature and duration of physical activity levels during PE classes. The 2000 SHPPS survey found that in a typical PE class (lasting an average of 45 minutes), students at all levels spent an average of 15.3 minutes participating in games, sports, or dance and 9.6 minutes doing skill drills (Burgeson et al., 2001). Of the 55.7 percent of high school students who reported participating in PE class in the 2003 YRBSS survey, 80.3 percent reported that they exercised or played sports for more than 20 minutes in the average PE class (CDC, 2004b). Simons-Morton and colleagues (1993) found that in a typical 30-minute elementary school PE class, the average child was vigorously active for only two to three minutes (approximately 9 percent of the class time).

Traditionally PE teachers have been trained to conduct classes around

FIGURE 7-2 High school students not engaging in recommended amounts of physical activity (neither moderate nor vigorous) by grade and sex, United States, 2001.

SOURCE: CDC, 2003.

a motor skill instruction paradigm. There are opportunities for exploring a variety of teaching methods that both optimize physical activity and that make PE classes more fun. Including a range of physical activity interests including dance and nontraditional activities such as Tai Chi and kick boxing is also important.

Recess is generally defined as unstructured time for physical activity during the school day. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Guidelines for School and Community Programs to Promote Lifelong Physical Activity Among Young People recommend that schools provide ample time for unstructured physical activity and that this time should complement, not substitute for, PE classes (CDC, 1997). Elementary schools differ greatly in their recess policies. While only a small minority of states actually require elementary schools to provide students with regularly scheduled recess, many more (22.4 percent) recommend this practice (Burgeson et al., 2001). Among elementary schools surveyed in the 2000 SHPPS, 71.4 percent provided recess for all grades, and 96.9 percent offered regularly scheduled recess during the school day for students in at least one grade. (Burgeson et al., 2001). Among these schools, students were scheduled to have recess an average of 4.9 days per week for an average of 30.4 minutes per day.

Alternative approaches for incorporating physical activity into the school day continue to be explored and include integrating brief episodes of physical activity into the classroom curriculum.

School-Based Interventions

There have been few studies examining the possible correlations between PE enrollments and physical activity levels. Using the 1990 YRBSS data, Pate and colleagues (1996) found that 59 percent of high-active students were enrolled in PE as compared to 29 percent of low-active students. As described below, several large-scale school-based intervention studies have demonstrated increases in physical activity in PE classes, but only in isolated smaller scale studies have school interventions increased physical fitness, reduced obesity, or increased physical activity outside of PE classes.

To date, interventions focused on elementary school children have been the most successful at increasing activity levels, with interventions such as Go For Health (Simons-Morton et al., 1997) and SPARK (Sallis et al., 1997) reporting significant increases in the amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity performed during PE classes. In the SPARK intervention, students in the classes taught by physical education specialists spent more time being physically active (40 minutes) than those in the teacher-led classes (33 minutes) or those in control classes (18 minutes) (Sallis et al., 1997).

The largest elementary-school-based intervention to date has been CATCH, a multicenter trial (described above) that tested the effectiveness of a cardiovascular health promotion program in 96 elementary schools. Students in CATCH intervention schools participated in significantly more moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during PE classes than did students in control schools, but significant improvements in physical fitness levels or body weight were not observed (Luepker et al., 1996). An assessment of CATCH 5 years later found that the proportion of PE time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity had been maintained in intervention schools, but vigorous activity levels declined (McKenzie et al., 2003). School-based programs are less likely to increase physical activity outside of PE classes, although students in the CATCH intervention schools did report participating in more vigorous physical activity during out-of-school hours, an effect that a 3-year follow-up study noted was still being maintained (Nader et al., 1999).

Although some elementary-school-based interventions have shown increased physical activity in PE classes, few have shown significant effects on physiological health risk variables such as body weight or composition. One notable exception was the South Australian Daily Physical Activity Program (Dwyer et al., 1983), which observed the effects of two interventions that markedly increased the exposure of elementary school children to PE. The first intervention emphasized participation in vigorous physical activity through endurance training for 75 minutes every day for 14 weeks, while the second maintained a traditional emphasis on motor-skill instruc-

tion but increased the duration and frequency to 75 minutes every day. Both of these interventions were compared to traditional PE classes for 30 minutes three days per week. Only the intervention that emphasized vigorous physical activity produced a significant reduction in skinfold thickness and an increase in objectively measured physical fitness, while traditional PE, even at increased frequency and duration, did not. The findings of this study suggest that physical education has the potential to improve body composition in children, but only if activity is at high intensity, with increases in frequency and duration. Physical education classes of 75 or more minutes are not feasible within most current school days; however, the impact of this intervention on students’ BMI encourages the development of approaches for increasing physical activity that can realistically be implemented.

The other PE intervention that has demonstrated significant effects on body weight was the Stanford Dance for Health intervention, which substituted popular and aerobic dance classes (40 to 50 minutes, three times per week, over 12 weeks) for the standard physical activity class (Flores, 1995). In a randomized controlled trial among mostly low-income African-American and Latino middle-school students, girls who were randomized to the dance intervention significantly improved their physical fitness and reduced their BMI gain compared to girls in the standard class. There were no significant differences among boys. As in the South Australian study, changes in fitness and body weight/fatness were seen when the content of PE was made more vigorous.

A small number of school-based studies have focused on increasing physical activity in older students. The Lifestyle Education for Activity Program was a group randomized trial that examined the effects of a comprehensive school-based intervention on high school girls’ physical activity levels. Girls in the intervention schools were significantly more likely to participate in vigorous physical activity, both in PE classes and in other settings, than girls in the control schools (Dishman et al., 2004). The Middle-School Physical Activity and Nutrition study tested the effects of an environmental and policy intervention on physical activity and fat intake in 24 middle schools. Boys in the intervention schools participated in significantly more physical activity than boys in the control schools, both in and out of PE classes. The same across-the-board effect was not observed for girls, although girls in the intervention schools did participate in more physical activity during PE classes (Sallis et al., 2003). The study found significant reductions in the BMIs of boys in the intervention schools as compared to boys in the control schools, based on self-reports of height and weight; however, similar results were not seen for girls. Issues regarding gender differences had been considered (e.g., the outside-of-PE component of the intervention was staffed primarily by female volunteers and the study

involved physical activities of interest to middle-school girls), but much remains to be learned about how to design interventions that impact physical activity levels in both boys and girls. A recent comprehensive review of school-based physical activity programs (Kahn et al., 2002) identified 12 well-designed programs that met the CDC’s Guide to Community Preventive Services criteria (Dwyer et al., 1983; Simons-Morton et al., 1991; Hopper et al., 1992, 1996; Vandongen et al., 1995; Donnelly et al., 1996; Fardy et al., 1996; Luepker et al., 1996; McKenzie et al., 1996; Sallis et al., 1997; Ewart et al., 1998; Manios et al., 1999; Harrell et al., 1999). These studies reported consistent increases in reported or observed time spent in physical activity in school, primarily through increases in moderate to vigorous physical activity in PE classes. Some of the studies also reported increases in energy expenditure and aerobic capacity. The effects on BMI and body fat, however, were minimal or inconsistent. Positive effects on physical activity were observed in both elementary school and high school studies, although the number of high school studies included in this review was small.

Inexpensive ways to enhance school breaks and recess periods to increase opportunities for physical activity have also been examined, including providing game equipment such as balls and painting school playground areas with markings for games (Jago and Baranowski, 2004).

Extracurricular Programs to Increase Physical Activity

One initiative that has shown a positive effect on physical activity is the Title IX legislation, which in recent decades increased the extent of interscholastic sports programs and participation, particularly for high school girls (Lopiano, 2000). However, these programs tend to serve only youth at the high school level, and only those who are attracted to competitive sports. The 2003 YRBSS nationwide survey found that 57.6 percent of students (grades 9 to 12) played on one or more sports teams during the previous year (CDC, 2004b). The 2000 SHPPS survey found that most middle and high schools had interscholastic sports teams, while only 49 percent offered intramural activities or PE clubs (Burgeson et al., 2001).

Research has shown that physical activity levels often decrease for middle- and high school students, especially among girls (Sallis, 1993; Pate et al., 1994; Trost et al., 2002). In those grades, there are fewer options for students who are not advanced athletes to be involved in physical activity. To fill that void, intramural sports and other physical activity opportunities—through clubs, programs, and lessons—can be tailored to meet the needs and interests of all students, with a wide range of abilities, who may lack the time, skills, or confidence to play interscholastic sports. Encourag-

ing such a range of physical activity options in local schools and communities, through the development of programs and provision of support, may involve not only schools, but also the private sector and nonprofit foundations and organizations. It is critically important that a focused effort be made to enhance funding and opportunities so that intramural sports teams, as well as nonteam sports and activities, become staples of school and after-school programs.

Next Steps

There are opportunities for schools to improve the extent and nature of the physical activity opportunities that are offered so that students can attain at least 50 percent of their daily recommended physical activity (or approximately 30 minutes) while in school. Few studies of physical activity during school have examined weight status or body composition measures; most studies have focused on changes in the intensity or duration of physical activity during PE classes. School-based interventions that have involved teacher training, PE curriculum changes, increases in duration or intensity of physical activity, and other changes have resulted in increased levels of activity and in some cases reported increases in energy expenditure and aerobic capacity. An expansion of physical activity opportunities available through the school may result in benefits not only for students’ health and well-being but also may potentially foster the formation of a lifelong practice of daily physical activity.

Schools should ensure that all children and youth participate in a minimum of 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity during the school day. This includes time spent being active during PE classes. This objective is equally important for young children in child development centers and other preschool and child-care settings, including Head Start programs—the benefits to young children include the nurturing and refinement of their gross motor development skills.

Furthermore, schools should expand the physical activity opportunities available through the school, including intramural and interscholastic sports programs, and other physical activity clubs, programs, and lessons that meet the needs and interests of all students. This includes physical activity programs both during the school day and after school.

Additionally, schools should promote walking and bicycling to school. As more thoroughly discussed in Chapter 6, schools should develop policies and promote programs that encourage these active ways of getting between school and home. Changes that are needed may include more support for crossing guards, bike racks, and education on pedestrian and biking safety.

Strategies and recommendations to achieve these goals include:

-

Schools should provide PE classes of 30 to 60 minutes’ duration on a daily basis. While attending these classes, children and youth should be engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity for at least 50 percent of class time. Schools should examine innovative approaches that include an array of diverse and fun activities to appeal to the broad range of student interests.

-

Child development centers, elementary schools, and middle schools should provide recess that includes a total of at least 30 to 60 minutes daily of physical activity.

-

Schools should offer a broad array of after-school programs, such as interscholastic sports, intramural sports, clubs, and lessons, that together meet the physical activity needs and interests of all students.

-

Schools and child development centers should support and encourage physical activity opportunities for teachers and staff for their own well-being and because they are important role models for their students.

-

Schools should be encouraged to extend the school day as a means of providing expanded instructional and extracurricular physical activity programs.

-

Regulations for managing Head Start and other publicly funded or licensed early-childhood-education programs should ensure that children engage in appropriate physical activity as part of the programs.

-

Congress, state legislatures, state education agencies, local governments, school boards, and parents should hold schools and child development centers responsible for providing students with recommended amounts of physical activity. Concurrently, these authorities should ensure that schools and child development centers have the resources needed to meet the applicable standards.

-

Schools should regularly evaluate the quantity and quality of their physical activity programs, and the results of these evaluations should be reported to the public.

The committee acknowledges the constraints and pressures on school boards and administrators, particularly limited resources and the focus on academic programs and homework to improve standardized test scores. Nevertheless, it urges schools and child-development centers to increase opportunities for students to participate in physical activity and to implement evidence-based programs. These institutions will need the help of federal, state, and local authorities, who should initiate and implement the necessary regulatory and curriculum changes. Such actions could well have influence beyond their nominal purposes. Programmatic requirements imposed by the state or district—which likely will be evaluated systematically, with results reported to the public—could provide the impetus for significant changes and innovative programs.

Much research is needed to identify effective school-based interventions for promoting and providing physical activity to children and youth. Specifically, large-scale studies are needed to identify ways in which modifications of physical education, school sports, intramural programs, and recess—singly and in combination—contribute to physical activity goals. It is important, moreover, to learn the effects of such interventions not only on physical activity during the school day, but also after school. Studies should also determine the influence of district or school-level policies on school practices and student physical activity. Furthermore, research is needed to determine the effects of school-based physical activity interventions on student academic performance, dietary and nutritional outcomes, classroom behavior, and social outcomes.

Research specific to preschool and child-care settings should emphasize feasible and generalizable interventions designed to increase physical activity (e.g., manipulations of outdoor play time), decrease sedentary behaviors (e.g., parenting skills interventions to reduce children’s screen time), and improve dietary behaviors (e.g., systematic exposure to fruits and vegetables in a positive context to enhance taste preferences).

CLASSROOM CURRICULA

Health Education Requirements and Practices

National education and health organizations recognize the important role that schools can play in fostering healthful behaviors among children and youth (Kann et al., 2001). Priorities for health education include behavioral skills development, a set amount of time devoted to energy balance in the classroom curricula, adequately trained teachers, and periodic curriculum evaluation (NASBE, 1990; Kann et al., 2001). A comprehensive set of guidelines and recommendations for school health programs has been developed by CDC (1997). In practice, health education standards of the Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards (1995), which are followed by most states and school districts, also emphasize the importance of teaching students behavioral skills—such as effective decision-making and goal-setting—thereby making healthful behaviors more likely.

National data show that 69 percent of states require health education curricula to include instruction on nutrition and dietary behaviors, and 62 percent require the inclusion of physical activity and fitness (Kann et al., 2001). In 69 percent of districts, schools are required to follow national, state, or district-level standards or guidelines; 77.8 percent of the schools use the National Health Education Standards (Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards, 1995; Kann et al., 2001). Assessment of

students’ acquired skills is weak, however; only 16 percent of states require that they be tested on health education topics (Kann et al., 2001).

Numerous topics—including safety, first aid, alcohol and tobacco use prevention, growth and development, and personal hygiene—need to be covered in health education classes varying by the ages of the students. In the 2000 survey, 75 percent of health courses and 51 percent of other courses included content on nutritional and dietary behavior, and 69 percent and 29 percent, respectively, addressed physical activity and fitness (Kann et al., 2001). An average total of about five hours per year is spent on topics related to nutritional and dietary behavior, and about four hours per year on physical activity and fitness (Kann et al., 2001).

Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity Curricula

As described below, research findings support the effectiveness of behavior-oriented curricula—based on self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback about behavior change efforts, incentives, and reinforcement methods—in promoting healthful food choices and physical activity. Skill-building activities, in which students engage in the desired behaviors and have a chance to practice new behaviors and receive feedback, are effective learning strategies.

However, there is still much to learn about the elements of nutrition and physical activity education programs that are key to changing behaviors and, subsequently, body weight. The most commonly used theoretical framework for developing behavior-based school interventions is social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986). “Self-efficacy,” in particular, or the confidence in one’s ability to perform a specific behavior, is a central concept in SCT. Self-efficacy is enhanced through skills building, practicing and mastering the behavior with feedback and reinforcement, and observing modeled behavior.

A recent review of 16 school-based cardiovascular risk factor prevention intervention studies found that interventions were most effective in changing cognitive variables, such as self-efficacy and outcome expectations, and were least effective in changing physiological variables such as body fatness (Resnicow and Robinson, 1997). However, these studies are difficult to compare because of the diversity of their intervention components and the primary outcomes targeted. Some interventions were only based on classroom curricula, while others include changes in the school food environment or PE classes.

Two of the most ambitious health behavior change interventions have been CATCH and Pathways, described above (Box 7-2). But despite tremendous commitments of resources and expertise, intervention effects were significant for some of the reported behavioral changes but not for the

objectively measured physiological changes, including BMI or body fatness (Luepker et al., 1996; Caballero et al., 1998; Davis et al., 1999). The specific effects of the classroom curricula could not be evaluated because the studies were implemented as multicomponent interventions, including individual-level intervention targets (e.g., student knowledge and behavior) and environmental intervention targets (e.g., school meals, PE classes).

An interesting contrast is provided by the results of the Planet Health intervention (Gortmaker et al., 1999), which aimed to reduce the prevalence of obesity among students in grades six through eight. Ten schools were randomized to intervention or control for a 2-year period, and the interventions were classroom-based only; they did not include school food service, physical activity, or other environmental-change components. Classroom intervention sessions, which featured behavioral skills development and strategies (e.g., self-assessment and goal-setting) were incorporated into different curriculum content areas; behaviors targeted for change included increases in fruit and vegetable intake, increases in physical activity, and decreases in television viewing time. At the end of the study, obesity prevalence among girls in the five intervention schools was significantly lower than among girls in the five control schools. Differences in obesity prevalence were not significant among boys. Analysis of changes in behavioral variables showed that decreases in television viewing were significantly associated with decreases in obesity prevalence among the girls. The reason for the lack of an intervention effect in boys is not clear. There are few controlled studies in this area and further research is needed.

Curriculum-only interventions have also resulted in significant reductions in BMI or skinfolds among both boys and girls. The Stanford Adolescent Heart Health Program targeted tenth-graders in a four-school randomized controlled trial (Killen et al., 1988). In addition to changes in body composition, the 20-session classroom curriculum also produced significant improvements in fitness.

Reducing Sedentary Behaviors

Television viewing time reduction has been examined in several school-based studies as a strategy for preventing obesity (Gortmaker et al., 1999; Robinson, 1999). In contrast to most other curriculum efforts, these intervention studies have shown positive effects on reducing the prevalence of obesity or weight gain. For example, Robinson (1999) examined the effects of the Stanford SMART (Student Media Awareness to Reduce Television) curriculum on changes in BMI among third- and fourth-grade children in two public elementary schools. Students in the intervention school received an 18-lesson, six-month curriculum designed solely to help children and families reduce television viewing time and videotape and video game use.

No other behaviors were targeted in the study in order to “isolate” the specific effects of reduced television viewing on changes in BMI. In addition to the classroom curriculum, parents also received newsletters and a television time-management monitor that allowed them to set time limits on the home television; 42 percent of parents reported that they actually installed the device. Results revealed significant reductions in BMI, triceps skinfold thickness, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratios among children in the intervention school compared with children in the control school, over a single school year.

The Planet Health intervention—a curriculum-based intervention for sixth- and seventh-grade students using behavioral choice and social cognitive approaches (discussed earlier)—also focused on reducing television viewing (Gortmaker et al., 1999). Other lessons included an emphasis on dietary and physical activity change. Teacher training sessions were held prior to implementation. Obesity prevalence decreased in girls in the inter-vention schools (from 23.6 percent to 20.3 percent) and increased in girls in the control schools (from 21.5 percent to 23.7 percent). For boys, obesity prevalence decreased in both groups, with no significant differences between groups. Number of television hours declined for both genders in the intervention schools as compared with controls and for girls in the intervention schools there was an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption.

The positive results of Stanford SMART and Planet Health suggest that obesity prevention efforts should involve reductions in sedentary television viewing time (see Chapter 8) and that school curricula should include television viewing reduction components.

Next Steps

Evidence from school intervention studies demonstrates some effectiveness of behavior-based nutrition and physical activity curricula. Evidence is most compelling from curricula for reducing television viewing, from vigorous PE interventions, and from large-scale, multicomponent intervention studies.

The extent to which schools are currently implementing such curricula, however, is unclear. Constraints include the limited availability of health educators who are trained in behavior-change methods, and the lack of sufficient time in the school day for specifically focusing on eating and physical activity behaviors. More staff training and the allocation of more time are two priorities. The impact of health education material can also be expanded by incorporating nutrition and physical activity information into science, math, history, social studies, and other courses.

Schools should ensure that nutrition, physical activity, and wellness concepts are taught throughout the curriculum from kindergarten through

high school. Schools should implement as part of the health curriculum an evidence-based program that includes a behavioral skills focus on promoting physical activity, healthful food choices, and energy balance and decreasing sedentary behaviors.

Given the limited resources in many schools and their varied priorities regarding the nature and duration of nutrition, health, and physical education classes and curricula, it is critically important for innovative approaches to be developed and evaluated to address obesity prevention in the schools. These approaches should involve evidence-based curricula that teach effective decision-making skills in the areas of diet and physical activity. Teacher training in health education and behavioral-change teaching methods is needed. The departments of education and health at the state and federal levels, with input from relevant professional organizations, should develop and evaluate pilot programs to explore innovative approaches to both staffing and teaching about wellness, healthful choices, nutrition, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors. Furthermore, it is hoped that health educators, school psychologists, and professional organizations (e.g., American Federation of School Teachers, American Psychological Association) will be brought into the discussions on how best to develop innovative curricula in this area.

ADVERTISING IN SCHOOLS

There have been growing concerns in recent years about the extent of commercial advertising in public schools and the influence that it may have on children’s decision-making both for foods and other goods (Consumers Union, 1990, 1995; Greenberg and Brand, 1993; Bachen, 1998; Levine, 1999). Branded products are often advertised to students in a variety of school venues. Examples of these venues include required in-school television viewing such as Channel One, school textbooks, corporate-sponsored classroom materials, sports equipment, school cafeteria foods, signage and equipment (refrigerated display cases), vending machine signage, uniform logos, advertising on school buses, product giveaways, coupons, incentive contests, book covers, mouse pads, and book clubs.

Commercial activities involving schools have been categorized as follows (GAO, 2000; Wechsler et al., 2001):

-

Product sales: short-term fundraising activities benefiting a specific student activity; cash or credit rebate programs; and commerce in products that benefit a district, school, or student activity (e.g., vending machine contracts; class ring contracts)

-

Direct advertising on school property: billboards, signs, and product displays; signs on school buses; corporate logos or brand names on

-

school supplies or equipment; ads in school publications; media-based advertising (e.g., Channel One News); and free samples and coupons

-

Indirect advertising: corporate-sponsored educational materials; teacher training; contests; incentive programs; and, in a small percentage of schools (<2 percent), lesson plans or curricula sponsored by companies (Wechsler et al., 2001)

-

Market research conducted through or at schools: questionnaires, taste tests, and Internet surveys.

Only limited data are available on the extent of advertising in schools. The 2000 SHPPS nationwide survey found that the majority of high schools (71.9 percent) have contracts with one or more companies to sell soft drinks at the school (Wechsler et al., 2001). The percentages at middle schools (50.4 percent) and elementary schools (38.2 percent) are lower but still significant (Wechsler et al., 2001). Of those schools with soft drink contracts, most (91.7 percent) receive a proportion of the sales; some of the contracts include incentives for increased sales such as equipment, supplies, or cash awards. Advertising by soft drink companies is allowed in the school building at 37.6 percent of the schools with contracts; advertising is allowed on school grounds at 27.7 percent; and advertising on school buses is allowed by only 2.2 percent (Wechsler et al., 2001).

Data from the SHPPS survey (Table 7-1) give an overview of some of the commercial involvement of schools. In the 19 schools visited for the GAO report, most of the advertising was seen in high schools; examples included advertising on scoreboards, vending machines, posters, and on promotional materials such as free book covers and product samples (GAO, 2000). In many schools television programming is provided through Channel One News4—10 minutes of news, music, contests, and public service announcements interspersed with 2 minutes of commercials, including advertisements for candy, food, and beverages.

Although there is little published research on school commercialism, there are some indications of increases in the extent of commercialism in schools. In a survey of high school principals in North Carolina, 51.1 percent of the 174 respondents believed that corporate involvement in their school had increased over the past 5 years (Di Bona et al., 2003), the largest involvement being in the form of incentive programs (41.4 percent). Such changes have been noted by the press. An analysis of media references to school commercialism has found significant increases over the past 6 years (Molnar, 2003).

TABLE 7-1 Schools That Allow Food Promotion or Advertising

|

|

Total Schools (%) |

|

|

Soft drink contracts: |

||

|

Have contract with company to sell soft drinks |

Elementary schools: |

38.2 |

|

Middle/junior high schools: |

50.4 |

|

|

Senior high schools: |

71.9 |

|

|

Of schools with soft drink contracts: |

|

|

|

Receive a specific percentage of soft drink sale receipts |

|

91.7 |

|

Receive sales incentives from companya |

Elementary schools: |

24.0 |

|

|