6

Articulating Validation Arguments

Accommodations are necessary to enable many students with disabilities and English language learners to participate in NAEP and other large-scale assessments. Because there is no definitive science to guide decisions about when an accommodation is needed or what kind is needed, there is always a risk that an accommodation will overcorrect or undercorrect in a way that further distorts a student’s performance and undermines validity. For this reason, it cannot simply be assumed that scores from standard and accommodated administrations are comparable.

Decisions about accommodations are often made on the basis of commonsense judgments about the nature of the disability or linguistic difficulty and about the concepts and skills to be evaluated on the assessment. These decisions are often made on the basis of beliefs that may not be supported by empirical evidence, either because the type of empirical evidence needed is not available or because available research is not consulted. This is the case both for determining which accommodations are right for individuals and for developing policy about allowable and nonallowable accommodations.

To investigate the extent to which accommodations for students with disabilities and English language learners may affect the validity of inferences based on scores from NAEP and other assessments, one must begin with a close look at the validation arguments that underpin these scores in general. Research can most effectively investigate the effects of accommodations if it is based on a well articulated validation argument that explicitly specifies the claims underlying the assessments and the inferences the assessments are designed to support, and also if it explicitly specifies possible counterclaims and competing inferences.

The research conducted in this area to date has, for the most part, been inconclusive (Sireci et al., 2003). This is not to say that the existing research is not useful. Indeed, many of the studies of accommodations on NAEP and other large-scale assessments have been well designed and implemented. However, as described in Chapter 5, they have for the most part focused on differences in scores for students taking tests with and without various accommodations. They have not investigated the comparability of scores obtained from accommodated and unaccommodated administrations, nor have they illuminated the extent to which similar inferences can be drawn about scores obtained under different conditions. In our view, research should more specifically address the central validity concerns that have been raised about the inferences that can be drawn from scores based on accommodated administrations, and this process should begin with articulation of the validation argument that underlies performance on the assessment.

One purpose that can be served by this report, therefore, is to suggest an alternative approach to research on the validity of scores from accommodated administrations. We do this by suggesting ways in which an inference-based validation argument for NAEP could be articulated. Such an argument would provide a basis for conducting validation research that systematically investigates the effects of different accommodations on the performance of students with disabilities and English language learners. Such a validation argument would also inform assessment design and development, since the effects of different alterations in task characteristics and in test administration conditions caused by accommodations could be better understood using this approach.

In this chapter we lay out a procedure for making a systematic logical argument about:

-

the skills and knowledge an assessment is intended to evaluate (target skills),

-

the additional skills and knowledge an individual needs to demonstrate his or her proficiency with the target skills (ancillary skills), and

-

the accommodations that would be appropriate, given the particular target and ancillary skills called for in a given assessment and the particular disability or language development profile that characterizes a given test-taker.

We begin with an analysis of the target and ancillary skills required to respond to NAEP reading and mathematics items. We then discuss procedures for articulating the validation argument using an approach referred to as evidence-centered design investigated by Mislevy and his colleagues (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004; Hansen et al., 2003; Mislevy et al., 2002, 2003). We illustrate the application of this approach with a sample NAEP fourth grade reading task. This example demonstrates how the suitability of various accommodations for

students with disabilities and English language learners in NAEP can be evaluated, based on an articulation of the target skills being measured and the content of the assessment tasks in a particular assessment.

TARGET AND ANCILLARY SKILLS REQUIRED BY NAEP READING AND MATHEMATICS ITEMS

The committee commissioned a review of NAEP’s reading and math frameworks with two goals in mind. First, we wanted to identify the constructs—targeted skills and knowledge—measured by the assessments and the associated ancillary skills required to perform the assessment tasks (see Hansen and Steinberg, 2004). We also wanted to evaluate the validation argument associated with use of specific accommodations on these assessments and to examine possible sources of alternate interpretations of scores. The resulting paper develops Bayes nets (“belief networks” that represent the interrelationships among many variables) to represent the test developer’s conceptions of target and ancillary skills and the role of specific accommodations. The authors analyzed these models to evaluate the validity of specific accommodations. The reader is referred to Hansen et al. (2003) for an in-depth treatment of this topic.

In the text that follows, we summarize the Hansen et al. analysis of the NAEP reading and mathematics frameworks. We then draw on the work of Hansen, Mislevy, and their colleagues (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004; Hansen et al., 2003; Mislevy et al., 2002, 2003) to provide a very basic introduction to the development of an inference-based validation argument. We then discuss two examples, one adapted from Hansen and Steinberg (2004); see also Hansen et al., (2003) (a visually impaired student taking the NAEP reading assessment) and one that the committee developed (an English language learner taking the NAEP reading assessment).

According to the framework document, the NAEP reading assessment “measures comprehension by asking students to read passages and answer questions about what they have read” (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, p. 5). NAEP reading tasks are designed to evaluate skills in three reading contexts: reading for literary experience, reading for information, and reading to perform a task (p. 8). The tasks and questions also evaluate students’ skills in four aspects of reading: forming a general understanding, developing interpretations, making reader-text connections, and examining content and structure (p. 11). These skills are considered by reading researchers to be components of reading comprehension. We note here that there are no explicit statements in the NAEP reading framework document to indicate that the assessment designers believe that decoding or fluency are part of the targeted proficiency (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004).

The NAEP mathematics assessment measures knowledge of mathematical content in five areas: number properties and operations, measurement, geometry, data analysis and probability, and algebra (National Assessment Governing

Board, 2001, p. 8). A second dimension of the math items is level of complexity: low, moderate, and high. Low-complexity items require recall and recognition of previously learned concepts. Moderate-complexity items require students to “use reasoning and problem solving strategies to bring together skill and knowledge from various domains.” Highly complex items require test-takers “to engage in reasoning, planning, analysis, judgment, and creative thought.” Each level of complexity includes aspects of knowing and doing math, such as “reasoning, performing procedures, understanding concepts, or solving problems” (p. 9). According to the frameworks, at each grade level approximately two-thirds of the assessment measures mathematical knowledge and skills without allowing access to a calculator; the other third allows the use of a calculator. Thus, the target constructs for the NAEP mathematics assessment seem to be content knowledge, reasoning and problem solving skills (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004), and, for some items, computational skills. Although content vocabulary (math vocabulary) is not specifically described as a skill being assessed, it seems to be an important aspect of the construct (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004).

Given the description of NAEP tasks in the mathematics and reading frameworks, Hansen and Steinberg (2004) identified several key ancillary skills that are required to respond to NAEP items, as shown in Tables 6-1 and 6-2. These

TABLE 6-1 Target and Ancillary Skills Required to Respond to Items on NAEP’s Reading Assessment

|

Knowledge and/or Skill |

Classification |

|

Comprehend written text |

Target skill |

|

Know vocabulary |

Ancillary skill |

|

Decode text |

Not specified as target skill |

|

Reading fluency |

Not specified as target skill |

|

See the item |

Ancillary skill |

|

Hear the directions |

Ancillary skill |

TABLE 6-2 Target and Ancillary Skills Required to Respond to Items on NAEP’s Mathematics Assessment

|

Knowledge and/or Skill |

Classification |

|

Mathematical reasoning |

Target skill |

|

Know content vocabulary |

Target skill |

|

Perform computations |

Target skill |

|

Comprehend written text |

Ancillary skill |

|

Know noncontent vocabulary |

Ancillary skill |

|

See the item |

Ancillary skill |

|

Hear the instructions |

Ancillary skill |

tables show a posible set of target and ancillary skills for the reading and mathematics assessments, respectively.

NATURE OF A VALIDATION ARGUMENT AND THE VALIDATION PROCESS

Students’ performance on assessment tasks is understood to accurately reflect the degree of their knowledge or skills in the area targeted. That is, if a test-taker’s response to an assessment task is correct or receives a high rating, one infers that he or she possesses a high degree of the relevant target skills or knowledge; one infers a correspondingly low degree if his or her response is incorrect or receives a low rating. For all test-takers, there are likely to be some possible alternative explanations for test performance. In a reading assessment task, for example, it may be possible for a test-taker to answer some of the tasks correctly simply by guessing or as a consequence of prior familiarity with the reading passage or its subject matter, despite poor reading skills. In this case, these potential alternative explanations for good performance weaken the claim or inference about the test-taker’s reading ability.

Alternative explanations can also potentially account for poor performance; for instance, if a test-taker is not feeling well on the day of the assessment and does not perform as well as he or she could, the results would not reflect his or her reading ability. Of most concern in this context are deficiencies in the specific ancillary skills required to respond to an item that may interfere with the measurement of the targeted constructs.

Validation is essentially the process of building a case in support of a particular interpretation of test scores (Kane, 1992; Kane et al., 1999; Messick, 1989, 1994). According to Bachman (in press, p. 267) the validation process includes two interrelated activities:

-

articulating an argument that provides the logical framework for linking test performance to an intended interpretation and use and

-

collecting relevant evidence in support of the intended interpretations and uses.

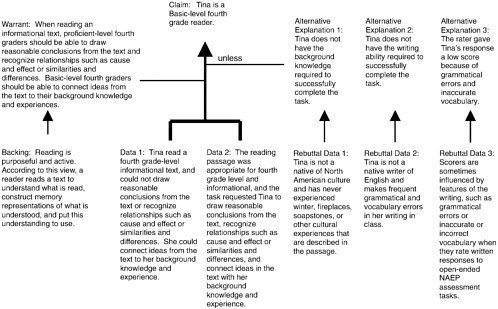

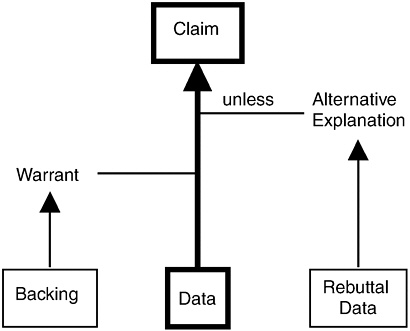

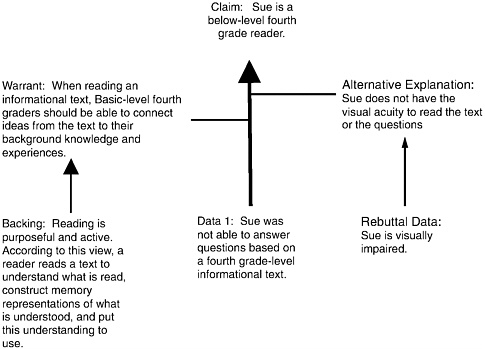

In their work on evidence-centered test design, Mislevy and his colleagues (Hansen and Steinberg, 2004; Hansen et al., 2003; Mislevy et al., 2003) expand on this notion, using Toulmin’s approach to the structure of arguments to describe an interpretive argument (Mislevy et al., 2003, p. 11; and Hansen and Steinbeg, 2004, p. 17) and use the following terminology to describe the argument:

FIGURE 6-1 Toulmin diagram of the structure of arguments.

SOURCE: Adapted from Hansen et al. (2003).

-

A claim is the inference that test designers want to make, on the basis of the observed data, about what test-takers know or can do. (Claims specify the target skills and knowledge.)

-

The data are the responses of test-takers to assessment tasks, that is, what they say or do.

-

A warrant is a general proposition used to justify the inference from the data to the claim.

-

A warrant is based on backing, which is derived from theory, research, or experience.

-

Alternative explanations are rival hypotheses that might account for the observed performance on an assessment task. (Alternative explanations are often related to ancillary skills and knowledge.)

-

Rebuttal data provide further details on the possible alternate explanations for score variation, and can either support or weaken the alternative explanations.

The structure of this argument is illustrated in Figure 6-1, in which the arrow from the data to the claim represents an inference that is justified on the basis of a warrant.

Illustrative Examples

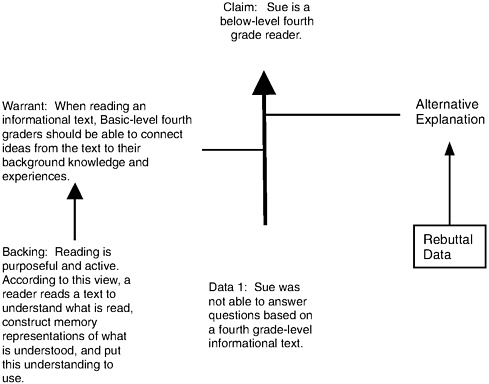

To illustrate the articulation of a validation argument for NAEP, we use a released NAEP fourth grade reading assessment task called “A Brick to Cuddle Up To,” which is described as an informational text (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a) (see Box 6-1). We use this task to illustrate our notion of how a validation argument can make it easier to identify target and ancillary skills, as well as appropriate accommodations for students with disabilities and English language learners.

Example 1: Sue, a Visually Impaired Student Taking a NAEP Reading Assessment

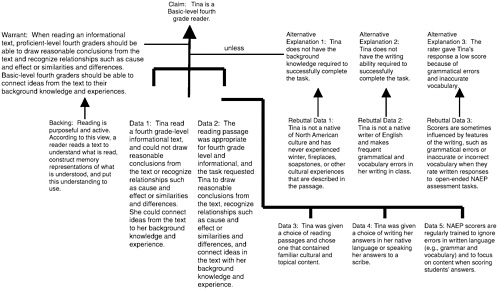

A validity argument in support of inferences to be made on the basis of scores for the “Brick to Cuddle Up To” reading tasks might look like the following:

|

Backing: |

[According to] cognitive research, reading is purposeful and active. According to this view, a reader reads a text to understand what is read, construct memory representations of what is understood, and put this understanding to use (p. 5). |

|

Warrant: |

When reading an informational text, Proficient-level fourth graders should be able to draw reasonable conclusions from the text, recognize relationships such as cause and effect or similarities and differences…. Basic-level fourth graders should be able to … connect ideas from the text to their background knowledge and experiences (p. 28). |

Suppose that Sue responds incorrectly to NAEP reading items.

|

Data: |

Sue responded incorrectly to tasks that required her to connect ideas from the text to her background knowledge and experience and that required her to draw reasonable conclusions from the text and to recognize relationships such as cause and effect or similarities and differences. |

|

Claim: |

Sue is a below Basic-level fourth grade reader.1 |

This argument is illustrated in Figure 6-2.

Validation Argument for Performance on NAEP Fourth Grade Reading Assessment Task. There are a number of possible alternative explanations for

|

BOX 6-1 Imagine shivering on a cold winter’s night. The tip of your nose tingles in the frosty air. Finally, you climb into bed and find the toasty treat you have been waiting for—your very own hot brick. If you had lived in colonial days, that would not sound as strange as it does today. Winters were hard in this New World, and the colonists had to think of clever ways to fight the cold. At bedtime, they heated soapstones, or bricks, in the fireplaces. They wrapped the bricks in cloths and tucked them into their beds. The brick kept them warm at night, at least for as long as its heat lasted. Before the colonists slipped into bed, they rubbed their icy sheets with a bed warmer. This was a metal pan with a long wooden handle. The pan held hot embers from the fireplace. It warmed the bedding so well that sleepy bodies had to wait until the sheets cooled before climbing in. Staying warm wasn’t just a bedtime problem. On winter rides, colonial travelers covered themselves with animal skins and warm blankets. Tucked under the blankets, near their feet, were small tin boxes called foot stoves. A foot stove held burning coals. Hot smoke puffed from small holes in the stove’s lid, soothing freezing feet and legs. When the colonists went to Sunday services, their foot stoves, furs, and blankets went with them. The meeting houses had no heat of their own until the 1800s. At home, colonial families huddled close to the fireplace, or hearth. The fireplace was wide and high enough to hold a large fire, but its chimney was large, too. That caused a problem: Gusts of cold air blew into the house. The area near the fire was warm, but in the rest of the room it might still be cold enough to see your breath. Reading or needlework was done by candlelight or by the light of the fire. During the winter, animal skins sealed the drafty windows of some cabins and blocked out the daylight. The living area inside was gloomy, except in the circle of light at the hearth. Early Americans did not bathe as often as we do. When they did, their “bathroom” was the kitchen, in that toasty space by the hearth. They partially filled a tub of cold water, then warmed it up with water heated in the fireplace. A blanket draped from chairs for privacy also let the fire’s warmth surround the bather. The household cooks spent hours at the hearth. They stirred the kettle of corn pudding or checked the baking bread while the rest of the family carried on their own fireside activities. So you can see why the fireplace was the center of a colonial home. The only time the fire was allowed to die down was at bedtime. Ashes would be piled over the fire, reducing it to embers that might glow until morning. By sunrise, the hot brick had become a cold stone once more. An early riser might get dressed under the covers, then hurry to the hearth to warm up. Maybe you’d enjoy hearing someone who kept warm in these ways tell you what it was like. You wouldn’t need to look for someone who has been living for two hundred years. In many parts of the country, the modern ways didn’t take over from the old ones until recently. Your own grandparents or other older people might remember the warmth of a hearthside and the joy of having a brick to cuddle up to. SOURCE: Used by permission of Highlights for Children, Inc., Columbus, OH. Copyright © 1991. Illustrations by Katherine Dodge. |

|

Questions for “A Brick to Cuddle Up To”

|

FIGURE 6-2 Validation argument for performance on NAEP fourth grade reading assessment task.

Sue’s poor performance. For example, her decoding skill or reading fluency might be weak, which could interfere with her comprehension of the text. Alternatively, it might be that although she is visually impaired, Sue took a regular-sized font version of the test. If we know that Sue is visually impaired, then this constitutes rebuttal data that supports this alternative explanation (Figure 6-3).

Visual Impairment: Alternative Explanation for Performance on NAEP Fourth Grade Reading Assessment Task. In this example, if it is known that Sue’s low score is a consequence of lack of visual acuity and that sight is an ancillary skill for the reading assessment, providing Sue with a large-font version of the test would allow her better access to the testing materials and would weaken the alternative explanation of poor vision as a reason for her performance. Another accommodation sometimes considered as a compensation for poor vision is having the test read orally. It is difficult to determine whether this accommodation is appropriate for the NAEP reading assessment, given that the reading framework does not state whether or not decoding and fluency are part of the

FIGURE 6-3 Alternative explanations for performance on NAEP fourth grade reading assessment task.

target construct. If the test were read aloud, Sue would not need to use her decoding and fluency skills in order to read the passage and respond to the questions. If decoding and fluency are considered to be an aspect of the target construct, then the read-aloud accommodation would alter that construct. If decoding and fluency are considered ancillary skills, then the read-aloud accommodation would simply provide Sue with easier access to the passage and questions so she could more accurately demonstrate her reading comprehension skills.

Example 2: Tina, an English Language Learner Taking a NAEP Reading Assessment

A validity argument in support of inferences to be made on the basis of scores for the “Brick to Cuddle Up To” would work the same way for English language learners as for students with disabilities. In this example, however, the data are different. Suppose that Tina, an English language learner, were able to respond correctly to some of the tasks and not others. The data might be as follows:

|

Data: |

Tina read the passage, “A Brick to Cuddle Up To,” which is a fourth grade-level informational text. Tina’s written answer to the question, “After reading this article, would you like to have lived during colonial times? What information in the article makes you think this?” was scored as “Basic” on a three-level scoring rubric of “basic,” “proficient” and “advanced.” This question is intended to assess “Reader/Text Connections,” and was a fairly difficult item, with only 20 percent of test-takers answering the question successfully (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, pp. 16-17.) |

|

Claim: |

Tina is a Basic-level fourth grade reader. |

This argument is illustrated in Figure 6-4. The figure highlights the fact that there are two sources of data in the argument. The first, labeled Data 1, consists of the test-taker’s observed response to the assessment task, as described above. The second source, labeled Data 2, consists of the characteristics of the assessment tasks. Considering the characteristics of the task as part of the validation argument is critical for an investigation of the effects of accommodations for two reasons. First, accommodations can be viewed as changes to the characteristics or conditions of assessment tasks. Second, the test-taker’s response is the result of an interaction between the test-taker and the task, and changing the characteristics or conditions of the task may critically alter this interaction in ways that affect the validity of the inferences that can be made on the basis of test performance. In the example above, some of the relevant characteristics of the task are:

-

the reading passage is developmentally appropriate for fourth graders,

-

the reading passage is classified as informational, and

-

the task requires the test-taker to connect ideas from the text to his or her background knowledge and experiences.

We have looked at the way in which an argument can support the claims or inferences an educational assessment was designed to support, but, as we have seen, there are a number of potential alternative explanations for any assessment results.2 Variations in either the attributes of test-takers or the characteristics of assessment tasks can in some cases account for variations in performance that are unrelated to what is actually being measured—the variation among test-takers in what they actually know and can do. In such cases, the validity of the intended inferences is weakened. With students with disabilities and English language

learners, test developers and administrators are presented with systematic variations in test-takers’ attributes—they are systematic in that they are consistently associated with these particular groups of test-takers. Hence, the attributes that identify these groups may constitute alternative explanations for variations in performance that are evident in scores, and thus these attributes may undermine validity.

When the characteristics or conditions of the assessment tasks are altered, as when test-takers are offered accommodations, another source of systematic variation is introduced. These alterations can yield results that are explained not by differences in what students know and can do, but by the accommodations themselves. Moreover, when different groups of test-takers interact with different kinds of accommodations, the results may vary and thus these interactions can also constitute alternative explanations for performance. Therefore, in evaluating the effects of accommodations on the validity of inferences, three kinds of alternative explanations need to be considered:

-

Performance may be affected systematically by attributes of individuals associated with specific groups, such as students with disabilities and English language learners.

-

Performance may be affected systematically by accommodations, changes in the characteristics, or conditions of assessment tasks.

-

Performance may be affected systematically by the interactions between the attributes of groups of test-takers and characteristics of assessment tasks.

One crucial distinction that psychometricians make is between construct-relevant and construct-irrelevant variance in test scores, that is, variance that is or is not related to the test-takers’ status with respect to the construct being assessed (Messick, 1989). All three of these alternative explanations could be viewed as potential sources of construct-irrelevant variance in test performance.

The case that an alternative explanation accounts for score variation would need to be based on rebuttal data that provides further details on the probable reasons for score variation. Seen in the context of a validation argument, the primary purpose of an assessment accommodation is to produce test results for which the possible alternative explanations, such as test-taker characteristics that are irrelevant to what is being measured, are weakened, while the intended inferences are not weakened.

The fourth grade NAEP reading task discussed earlier can be used to demonstrate how one or more alternative explanations might work and the nature of the rebuttal data that might support them. Suppose Tina is an English language learner whose family’s cultural heritage is not North American and who is not familiar with some of the concepts presented in the passage, such as winter, fireplaces, and soapstones. In this case, it could be that Tina’s lack of familiarity

with some of the cultural elements of the passage, rather than inadequate reading proficiency, constitutes an alternative explanation for her performance; if this is true, it weakens the intended inference. It may well be that Tina’s reading is better than the basic level described for fourth grade but that her lack of familiarity with important concepts prevented her from being able to answer the questions based on this passage correctly. The components of this argument are illustrated in Figure 6-5.

Exploring and generating alternative explanations for performance can be done only in the context of clear statements about the content and skills the task is intended to assess. To demonstrate how this type of information can be used in developing a validation argument, the same example can be tied to NAEP’s documentation of the content and skills targeted by its fourth grade reading assessment. The NAEP Reading Framework explicitly recognizes that background knowledge is a factor in test performance but describes this factor as one that contributes to item difficulty. The framework document notes that “Item difficulty is a function of … the amount of background knowledge required to respond correctly” (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, p. 21). This statement leaves unanswered the question of whether or not background knowledge is crucial to the claim, or intended inference; in other words it does not specify whether background knowledge is a part of what is being assessed.

If the test-taker’s degree of background knowledge is not part of the construct or claim, then it constitutes a potential source of construct-irrelevant variance. Furthermore, since item difficulty is essentially an artifact of the interaction between a test-taker and an assessment task (Bachman, 2002b), it would seem that the critical source of score variance that needs to be investigated in this case is not the task characteristic—the content of the reading passage—but rather the interaction between the test-taker’s background knowledge and that content.

A second alternative explanation for Tina’s performance in the example can be found in the nature of the expected response, and how this was scored. Consider an example: “After reading this article, would you like to have lived during colonial times? What information in the article makes you think this? (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, p. 41).

This question is intended to assess “reader/text connections,” and test-takers are expected to respond with a “short constructed response” (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003a). This particular question is scored using a rubric3 that defines three levels: “evidence of complete comprehension,” “evidence of surface or partial comprehension,” and “evidence of little or no comprehension” (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, p. 41). Tina’s answer was scored as showing “evidence of little or no comprehension.” The descriptor for this score level is as follows (National Assessment Governing Board, 2002a, p. 41):

These responses contain inappropriate information from the article or personal opinions about the article but do not demonstrate an understanding of what it was like to live during colonial times as described in the article. They may answer the question, but provide no substantive explanation.

The fact that this question requires students to write a response in English provides a second alternative explanation; specifically, that Tina’s first language is not English, and her writing skills in English are poor. This also points to a third alternative explanation, that the individual who scored Tina’s answer gave her a low score because of the poor quality of her writing. This potential problem with the scoring of English language learners’ written responses to academic achievement test tasks is discussed in National Research Council (1997b), which points out that “errors … result from inaccurate and inconsistent scoring of open-ended performance-based measures. There is evidence the scorers may pay attention to linguistic features of performance unrelated to the content of the assessment” (p. 122). These additional alternative explanations and the rebuttal evidence are also presented in Figure 6-5.

To understand what constitutes an inappropriate or invalid accommodation, as well as to describe current accommodations or to design new accommodations that may be more appropriate for different groups of test-takers, a framework for systematically describing the characteristics of assessment tasks is needed. Bachman and Palmer (1996) present a framework of task characteristics that may be useful in describing the ways in which the characteristics and conditions of assessment tasks are altered for the purpose of accommodating students with disabilities and English language learners. This framework includes characteristics of the setting, the rubric, the input, and the expected response, as well as the relationships between input and response.

Bachman and Palmer maintain that these characteristics can be used to describe existing assessment tasks as well as to provide a basis for designing new types of assessment tasks. By changing the specific characteristics of a particular task, test developers can create an entirely new task. Accommodations that are commonly provided for students with disabilities or English language learners can also be described in terms of alterations in task characteristics, as in Table 6-3.

Task characteristics can be altered in such a way that the plausibility of alternative explanations for test results is lessened. This can be illustrated with the example used earlier, in which there were three possible alternative explanations for Tina’s poor performance on the reading assessment. To weaken the first alternative explanation, that Tina’s poor performance is the result of her lack of familiarity with the cultural content of the reading passage, test developers would need to control a characteristic of the input—in this case the content of the texts used in the assessment—to ensure that the texts presented to test-takers are not so unfamiliar as to interfere with their success on the assessment. One way to achieve this is to include students with disabilities and English language learners in the

TABLE 6-3 Task Characteristics Altered by Various Accommodations

|

Accommodation |

Task Characteristics Altered |

|

Individual and small-group administrations* |

Setting—participants |

|

Multiple sessions* |

Setting—time of assessment |

|

Special lighting* |

Setting—physical characteristics |

|

Extended time* |

Rubric—time allotment |

|

Oral reading of instructions* |

Setting—participants Input—channel and vehicle of language of input |

|

Large print* |

Input—graphology |

|

Bilingual version of test* |

Input—language of input (Spanish vs. English) |

|

Oral reading in English* |

Setting—participants Input—channel of input (oral L1 vs. written L1) |

|

Oral reading in native language* |

Setting—participants Input—language and channel of input (oral L1 vs. written L2) |

|

Braille writers* |

Setting—physical characteristics-equipment Expected response—channel of response |

|

Answer orally* |

Expected response—channel of response |

|

Scribe* |

Setting—participants Expected response—channel of response |

|

Tape recorders |

Setting—physical characteristics-equipment, equipment Expected response—channel of response (oral vs. written) |

|

*Accommodation provided in NAEP. |

|

pretesting of items, and possibly to pretest items using cognitive labs. Nevertheless, even with a very large bank of pretested texts, there will still be some probability that a particular test-taker will be unfamiliar with a given text, and this interaction effect will be very difficult to eliminate entirely.

To weaken the second alternative explanation, that Tina’s poor performance on reading assessment is the result of poor writing skills (which are not being assessed), either or both of two characteristics of the expected response—language or mode of response—could be altered. If Tina can read and write reasonably well in her native language, she might be permitted to write her responses in her native language. If she cannot write well in her native language but is reasonably fluent orally in English, then she could be permitted to speak her answers to a scribe, who would write them for her. If she is also not fluent orally in English, then she could be permitted to speak her answers in her native language to a scribe. The appropriateness of these alterations of course depends on the targeted construct. These alterations in task characteristics are shown in Table 6-4. These different accommodations provide data that weaken the possible alternative arguments and thus strengthen the inferences that were intended to be made based on Tina’s scores.

TABLE 6-4 Alterations in Task Characteristics as a Consequence of Accommodations

|

Task Characteristic |

Unaccommodated Task |

Accommodated Task 1 |

Accommodated Task 2 |

Accommodated Task 3 |

|

Language of response |

English |

Native language |

English |

Native language |

|

Channel of response |

Visual: Writing |

Visual: Writing |

Oral: Speaking |

Oral: Speaking |

To weaken the third alternative explanation, that Tina’s poor reading performance is the result of the scorer’s using the wrong scoring criteria, the test developers need to control two characteristics of the scoring process: the criteria used for scoring and the scorers themselves. Such corrections are handled most effectively through rigorous and repeated scorer training sessions.

Figure 6-5 portrays the relationships between the alternative explanations, rebuttal data, and types of data needed to weaken the alternative explanations.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In this chapter we have discussed the components of the kind of validation argument that underlies the intended inferences to be made from any assessment. We have illustrated how intended inferences, or claims, about test-takers’ target skills or knowledge need to be based both on warrants that are backed by relevant theory or research findings, and on data. These data consist of two types: (1) the test-taker’s response to the assessment task and (2) the characteristics of the assessment task. We have explained that a variety of test-takers’ characteristics, such as disabilities, insufficient proficiency in English, or lack of cultural knowledge, can constitute alternative explanations for their performance on assessments. We have also discussed the ways specific accommodations can be described in terms of specific aspects of the assessment tasks and administration procedures.

The committee has reviewed a variety of materials about the NAEP assessment (National Assessment Governing Board [NAGB], 2001, 2002a, 2002b; National Center for Education Statistics, 2003a, 2003b) and has heard presentations by NAEP and NAGB officials about these topics. In light of the validity issues related to inclusion and accommodations for students with disabilities and English language learners that have been discussed, we draw the following conclusions:

CONCLUSION 6-1: The validation argument for NAEP is not as well articulated as it should be with respect to inferences based on accommodated versions of NAEP assessments.

CONCLUSION 6-2: Even when the validation argument is well articulated, there is insufficient evidence to support the validity of inferences based on alterations in NAEP assessment tasks or administrative procedures for accommodating students with disabilities and English language learners.

On the basis of these conclusions we make three recommendations to NAEP officials. Although these recommendations are specific to NAEP, we strongly urge the sponsors of other large-scale assessment programs to consider them as well.

RECOMMENDATION 6-1: NAEP officials should identify the inferences that they intend should be made from its assessment results and clearly articulate the validation arguments in support of those inferences.

RECOMMENDATION 6-2: NAEP officials should embark on a research agenda that is guided by the claims and counterclaims for intended uses of results in the validation argument they have articulated. This research should apply a variety of approaches and types of evidence, such as analyses of test content, test-takers’ cognitive processes, criterion-related evidence, and other studies deemed appropriate.

RECOMMENDATION 6-3: NAEP officials should conduct empirical research to specifically evaluate the extent to which the validation argument that underlies each NAEP assessment and the inferences the assessment was designed to support are affected by the use of particular accommodations.