Executive Summary

Nothing is more fundamental to life than water. Not only is water a basic need, but adequate safe water underpins the nation’s health, economy, security, and ecology. The strategic challenge for the future is to ensure adequate quantity and quality of water to meet human and ecological needs in the face of growing competition among domestic, industrial–commercial, agricultural, and environmental uses. To address water resources problems likely to emerge in the next 10–15 years, decision makers at all levels of government will need to make informed choices among often conflicting and uncertain alternative actions. These choices are best made with the full benefit of research and analysis.

In June 2001, the Water Science and Technology Board of the National Research Council (NRC) published a report that outlined important areas of water resources research that should be addressed over the next decade in order to confront emerging water problems. Envisioning the Agenda for Water Resources Research in the Twenty-first Century was intended to draw public attention to the urgency and complexity of future water resource issues facing the United States. The report identified the individual research areas needed to help ensure that the water resources of the United States remain sustainable over the long run, with less emphasis on the ways in which the setting of the water research agenda, the conduct of such research, and the investment allocated to such research should be improved.

Subsequent to release of the Envisioning report, Congress requested that a new NRC study be conducted to further illuminate the state of the water resources research enterprise. In particular, the study charge was to (1) refine and enhance the recent findings of the Envisioning report, (2) examine current and historical patterns and magnitudes of investment in water resources research at the federal

level and generally assess its adequacy, (3) address the need to better coordinate the nation’s water resources research enterprise, and (4) identify institutional options for the improved coordination, prioritization, and implementation of research in water resources. The study was carried out by the Committee on Assessment of Water Resources Research, which met five times over the course of 15 months.

The committee was motivated by considering the following central questions about the state of the nation’s water resources: (1) will drinking water be safe; (2) will there be sufficient water to both protect environmental values and support future economic growth; (3) can effective water policy be made; (4) will water quality be enhanced and maintained; (5) will our water management systems adapt to climate change? If the answers to even some of the questions above are “no,” it would portend a future fraught with complex water resource problems but with limited institutional ability to respond. Knowledge and insight gained from a broad spectrum of natural and social science research on water resources are key to avoiding these undesirable scenarios.

Two realities helped to shape the scope of the study and have illuminated the inherent difficulties in creating a national agenda for water resources research. First, the type and quantity of research that will be needed to address current and future water resources problems are unlikely to be adequate if no action is taken at the federal level. For many reasons (as discussed in Chapter 1), the states and nongovernmental organizations have limited incentives and resources to invest in water resources research. Furthermore, most states are experiencing an increasing number of complex water problems—some of which cross state lines—and they have to respond to important federal mandates. This suggests a more central role for the federal government in producing the necessary research to inform water resources issues. Second, water resources problems do not fall logically or easily within the purview of a single federal agency but, rather, are fragmented among nearly 20 agencies. As water resource problems increase in complexity, even more agencies may become involved. The present state of having uncoordinated and mission-driven water resources research agendas within the federal agencies will have to be changed in order to surmount future water problems.

Chapter 2 of this report analyzes the history of federally funded water resources research in an effort to understand how the research needed to solve tomorrow’s problems may compare with the research undertaken in the past, and to illuminate how U.S. support for water resources research in the 20th century has fluctuated in response to important scientific, political, and social movements. Federal support of water-related research developed slowly during much of the 1800s and early 1900s, beginning with federal involvement in the development of rivers for navigation, flood control, and storage of water for irrigation. It was not until the 1950s that Congress committed to supporting a comprehensive pro-

gram of water resources research. The short-lived commitment peaked during the 1960s when Congress and the executive branch shared a similar view that the federal role in water entailed funding its development for human use while reducing problems of pollution. By the 1970s, growing interest in environmental protection conflicted with water development, which splintered the policy consensus and cast the federal government into more of a regulatory role while deemphasizing its role in promoting economic growth through water resources development.

Administrations of the 1980s and 1990s asserted a more limited federal role in water resources research, believing that research should be closely connected to helping to meet federal agency missions or to addressing problems beyond the scope of the states or the private sector. Congress, on the other hand, generally supported a broader approach to water research, but one that it could actively supervise through the legislative and appropriations process. A consequence of the devolving of responsibility for water resources research back to the states was the neglect of long-term, basic research as opposed to the favoring of applied research that would lead to more immediate results.

Over the last 50 years, the priority elements of a national water resources research agenda have been identified in widely varying ways by many organizations and reports. Many general topics of concern—for example, water-based physical processes, availability of water resources for human use and benefit, and hydrology–ecology relationships—have appeared repeatedly over the decades, while others, such as the impact of climate change and newly discovered waterborne contaminants, are recent topics. The reappearance of some of the same topics over time suggests that the nation’s research programs, both individually and collectively, have not responded in an adequate manner and that there is no structure in place to make use of the research agendas generated by various expert groups. Indeed, at the national level there is no coordinated process for considering water resources research needs, for prioritizing them for funding purposes, or for evaluating the effectiveness of research activities.

In the face of the historical inability to mount an effective, broadly conceived national program of water resources research, it is reasonable to ask, “Why bother with yet another comprehensive proposal?” The answer lies in the sheer number of water resource problems (as illustrated in Chapter 1) and the fact that these problems are growing in both number and intensity. To address these problems successfully, the nation must invest not only in applied research but also in fundamental research that will form the basis for applied research a decade hence. A repeat of past efforts will likely lead to enormously adverse and costly outcomes for the status and condition of water resources in almost every region of the United States.

A METHOD FOR SETTING PRIORITIES OF A NATIONAL RESEARCH AGENDA

The solution to water resource problems is necessarily sought in research—inquiry into the basic natural and societal processes that govern the components of a given problem, combined with inquiry into possible methods for solving these problems. In many fields, the formulation of explicit research priorities has a profound effect on the conduct of research and the likelihood of finding solutions to problems.

Water resources research areas were extensively considered in the Envisioning report, resulting in a detailed, comprehensive list of 43 research needs, grouped into three categories. The category of water availability emphasizes the interrelated nature of water quantity and water quality problems, and it recognizes the increasing pressures on water supply to provide for both human and ecosystem needs. The category of water use includes not only research questions about managing human consumptive and nonconsumptive use of water, but also about the use of water by aquatic ecosystems and endangered or threatened species. The third category, water institutions, emphasizes the need for research into the economic, social, and institutional forces that shape both the availability and use of water. Interestingly, input from federal and state government representatives gathered during the course of this project confirmed the importance of many of the 43 topics.

Rather than focusing on a topic-by-topic research agenda, this report identifies overarching principles to guide the formulation and conduct of water research. Indeed, statements of research priorities developed by a group of scientists or managers can, depending on the individuals, have a relatively narrow scope. In recent years, the limitations of discipline-based perspectives have become clear, as researchers and managers alike have recognized that water problems relevant to society necessarily integrate across physical, chemical, biological, and social sciences. Furthermore, research priorities should shift as new problems emerge and past problems are mitigated or brought under control through scientifically informed policy and actions. Thus, Chapter 3 provides a mechanism for reviewing, updating, and prioritizing the current water resources research agenda (as expressed in the Envisioning report) and subsequent versions of the agenda. This mechanism is much more than a summing up of the priorities of the numerous federal agencies, professional associations, and federal committees. Rather, it consists of six questions or criteria (listed below) that can be used to assess individual research priorities and thus to assemble (and periodically review) a responsive and effective national research agenda.

-

Is there a federal role in this research area? This question is important for evaluating the “public good” nature of the water resources research area. A federal role is appropriate in those research areas where the benefits of such research

-

are widely dispersed and do not accrue only to those who fund the research. Furthermore, it is important to consider whether the research area is being or even can be addressed by institutions other than the federal government.

-

What is the expected value of this research? This question addresses the importance attached to successful results, either in terms of direct problem solving or advancement of fundamental knowledge of water resources.

-

To what extent is the research of national significance? National significance is greatest for research areas (1) that address issues of large-scale concern (for example, because they encompass a region larger than an individual state), (2) that are driven by federal legislation or mandates, and (3) whose benefits accrue to a broad swath of the public (for example, because they address a problem that is common across the nation). Note that while there is overlap between the first and third criteria, research may have public good properties while not being of national significance, and vice versa.

-

Does the research fill a gap in knowledge? If so, it should clearly be of higher priority than research that is duplicative of other efforts. Furthermore, there are several common underlying themes that, given the expected future complexity of water resources research, should be used to evaluate research areas:

-

the interdisciplinary nature of the research

-

the need for a broad systems context in phrasing research questions and pursuing answers

-

the incorporation of uncertainty concepts and measurements into all aspects of research

-

how well the research addresses the role of adaptation in human and ecological response to changing water resources

-

These themes, and their importance in combating emerging water resources problems, are described in detail in Chapter 3.

-

How well is this research area progressing? The adequacy of efforts in a given research area can be evaluated with respect to the following:

-

current funding levels and funding trends over time

-

whether the research area is part of the agenda of one or more federal agencies

-

whether prior investments in this type of research have produced results (i.e., the level of success of this type of research in the past and why new efforts are warranted)

-

-

How does the research area complement the overall water resources research portfolio? When applied to federal research and development, the portfolio concept is invoked to mean a mix of fundamental and applied research; of shorter-term and longer-term research; of agency-based, contract, and investigator-driven research; and of research that addresses both national and region-specific problems—with data collection to support all of the above. Indeed, the priority-setting process should be as much dedicated to ensuring an appropriate balance and mix of research efforts as it is to listing specific research topics.

The following conclusions and recommendations are made about the creation and refinement of a national portfolio of water resources research.

The 43 research topics from the Envisioning report are the current best statement of research needs, although this list is expected to change as circumstances and knowledge evolve. Water resource issues change continuously, as new knowledge reveals unforeseen problems, as changes in society generate novel problems, and as changing perceptions by the public reveal issues that were previously unimportant. Periodic reviews of and updates to the priority list are needed to ensure that it remains not only current but proactive in directing research toward emerging problems.

An urgent priority for water resources research is the development of a process for regularly reviewing and revising the entire portfolio of research being conducted. The six questions listed above are helpful for assessing both the scope of the entire water resources research enterprise and the nature, urgency, and purview of individual research areas. Addressing these questions should ensure that the vast scope of water resources research carried out by the numerous federal and state agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and academic institutions remains focused and effective.

The research agenda should be balanced with respect to time scale, focus, source of problem statement, and source of expertise. Water resources research ranges from long-term and theoretical studies of basic physical, chemical, and biological processes to studies intended to provide rapid solutions to immediate problems. The water resources research enterprise is best served by developing a mechanism for ensuring that there is an appropriate balance among the different types of research, so that both the problems of today and those that will emerge over the next 10–15 years can be effectively addressed.

The context within which research is designed should explicitly reflect the four themes of interdisciplinarity, broad systems context, uncertainty, and adaptation. The current water resources research enterprise is limited by the agency missions, the often narrow disciplinary perspective of scientists, and the

lack of a national perspective on perceived local but widely occurring problems. Research patterned after the four themes articulated above could break down these barriers and promise a more fruitful approach to solving the nation’s water resource problems.

STATUS AND EVALUATION OF WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH IN THE UNITED STATES

In order to evaluate the current investment in water resources research, the committee collected budget data and narrative information in the form of a survey from the major federal agencies and significant nonfederal organizations that are conducting water resources research. The format of the survey was similar to an accounting of water resources research that occurred from 1965 to 1975 by the Committee on Water Resources Research of the Federal Council for Science and Technology. This earlier effort entailed annually gathering budget information from all relevant federal agencies in 60 categories of water resources research. In order to support a comparison of the current data with past information, the NRC committee adopted a modified version of the earlier model, using most of the same categories and subcategories of water resources research. In January 2003, the survey was submitted to all of the federal agencies that either perform or fund water resources research and to several nonfederal organizations that had annual expenditures of at least $3 million during one of the fiscal years covered by the survey. See Table 4-1 for a complete list of respondents.

The survey consisted of five questions related to water resources research (see Box 4-1). In the first question, the liaisons were asked to report total expenditures on research in fiscal years 1999, 2000, and 2001 for 11 major categories (and 71 subcategories) of water resources research. (All data collection activities were explicitly excluded from the survey.) The remaining questions were posed to help give the committee a better understanding of current and projected future activities of the agencies, to provide a qualitative understanding of how research performance is measured, and to gauge the agencies’ mix of research, in terms of fundamental vs. applied, internal vs. external, and short-term vs. long-term research. Responses to the survey were submitted in written form and orally at the third committee meeting, held April 29–May 1, 2003, in Washington, D.C.; revised survey responses submitted by the liaisons in summer 2003 reflected corrections and responded to specific requests from the committee.

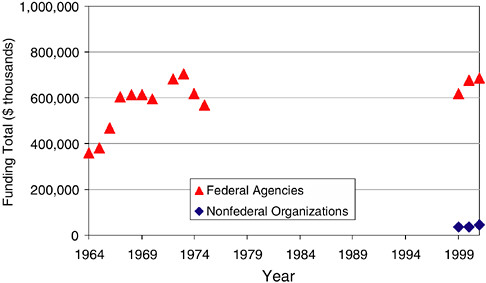

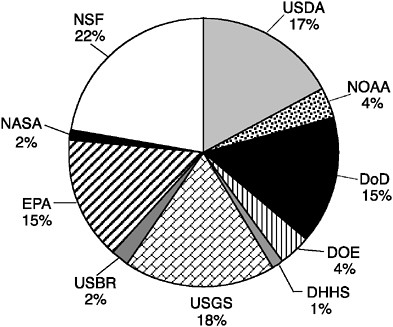

Evaluation of the submitted information included a trends analysis for the total amount of water resources research funding and for the funding of the 11 major categories of water resources research. The total budget for water resources research from 1965 to 2001 and the year 2000 breakdown by federal agency are shown in Figures ES-1 and ES-2. The budget data were also analyzed to determine the extent to which the 43 high-priority research areas in the Envisioning report are being addressed. Finally, the committee qualitatively assessed the

FIGURE ES-1 Total expenditures on water resources research by federal agencies and nonfederal organizations, 1964–2001. Values reported are FY2000 dollars. No survey data are available for years 1976–1988.

FIGURE ES-2 Agency contributions as a percentage of the total federal funding for water resources research in 2000.

balance of the current national water resources research portfolio (defined as the sum of all agency-sponsored research activities). The following conclusions and recommendations stem directly from these evaluations.

Real levels of total spending for water resources research have remained relatively constant (around $700 million in 2000 dollars) since the mid 1970s. When Category XI (aquatic ecosystems) is subtracted from the total funding, there is a very high likelihood that the funding level has actually declined over the last 30 years. It is almost certain that funds in Categories III (water supply augmentation and conservation), V (water quality management and protection), VI (water resources planning and institutional issues), and VII (resources data) have declined severely since the mid 1970s. All statements about trends are supported by a quantitative uncertainty analysis conducted for each category.

Water resources research funding has not paralleled growth in demographic and economic parameters such as population, gross domestic product (GDP), or budget outlays (unlike research in other fields such as health). Since 1973, the population of the United States has increased by 26 percent, the GDP and federal budget outlays have more than doubled, and federal funding for all research and development has almost doubled, while funding for water resources research has remained stagnant. More specifically, over the last 30 years water resources research funding has decreased from 0.0156 percent to 0.0068 percent of the GDP, while the portion of the federal budget devoted to water resources research has shrunk from 0.08 percent to 0.037 percent. The per capita spending on water resources research has fallen from $3.33 in 1973 to $2.40 in 2001. Given that the pressure on water resources varies more or less directly with population and economic growth, and given sharp and intensifying increases in conflicts over water, a new commitment will have to be made to water resources research if the nation is to be successful in addressing its water and water management problems over the next 10–15 years.

The topical balance of the federal water resources research portfolio has changed since the 1965–1975 period, such that the present balance appears to be inconsistent with current priorities as outlined in Chapter 3. Research on social science topics such as water demand, water law, and other institutional topics, as well as on water supply augmentation and conservation, now garners a significantly smaller proportion of the total water research funding than it did 30 years ago. When the current water resources research enterprise is compared with the list of research priorities noted in the Envisioning report, it becomes clear that significant new investment must be made in water use and institutional research topics if the national water agenda is to be addressed adequately. If enhanced funding to support research in these categories is not diverted from

other categories (which may also have priority), the total water research budget will have to be enhanced.

The current water resources research portfolio appears heavily weighted in favor of short-term research. This is not surprising in view of the de-emphasis of long-term research in the portfolios of most federal agencies. It is important to emphasize that long-term research forms the foundation for short-term research in the future. A mechanism should be developed to ensure that long-term research accounts for one-third to one-half of the portfolio.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should develop guidance to agencies on reporting water resources research by topical categories. Understanding the full and multiple dimensions of the federal investment in water resources research is critical to making judgments about adequacy. In spite of clearly stated OMB definitions of research, agencies report research activity unevenly and inconsistently. Failure to fully account for all research activity undermines efforts by the administration and Congress to understand the level and distribution of water resources research. This problem could be remedied if OMB required agencies to report all research activity, regardless of budget account, in a consistent manner.

DATA COLLECTION AND MONITORING

Although data collection was excluded from the water resources research survey conducted by the committee, the long-term monitoring of hydrologic systems and the archiving of the resulting data are critical to the water resources research enterprise of the nation. Data are essential for understanding physicochemical and biological processes and, in most cases, provide the basis for predictive modeling. Long-term consistent records of data, which capture the full range of interannual variability, are especially essential to understanding and predicting low-frequency, high-intensity events. Furthermore, federal agencies are instrumental in developing new monitoring approaches, in validating their efficacy through field studies, and in managing nationwide monitoring networks over long periods. The following conclusions and recommendations address the need for investments in basic data collection and monitoring.

Key legacy monitoring systems in areas of streamflow, groundwater, sediment transport, water quality, and water use have been in substantial decline and in some cases have nearly been eliminated. These systems provide data necessary for both research (i.e., advancing fundamental knowledge) and practical applications (e.g., for designing the infrastructure required to cope with hydrologic extremes). Despite repeated calls for protecting and expanding moni-

toring systems relevant to water resources, these trends continue for a variety of reasons.

The consequences of the present policy of neglect associated with water resources monitoring will not necessarily remain small. New hydrologic problems are emerging that are of continental or near continental proportions. The scale and the complexity of these problems are the main arguments for improvements to the in situ data collection networks for surface waters and groundwater and for water demand by sector. It is reasonable to expect that improving the availability of data, as well as improving the types and quality of data collected, should reduce the costs for many water resources projects.

COORDINATION OF WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH

Coordination of the water resources research enterprise is needed to make deliberative judgments about the allocation of funds and scope of research, to minimize duplication where appropriate, to present Congress and the public with a coherent strategy for federal investment, and to facilitate the large-scale multiagency research efforts that will likely be needed to deal with future water problems. Unfortunately, water resources research across the federal enterprise has been largely uncoordinated for the last 30 years, although there have been periodic ad hoc attempts to engage in interagency coordination during that time. The lack of coordination is partly responsible for the topical and operational gaps apparent in the current water resources research portfolio. Thus, although the federal agencies are carrying out their mission-driven research, most of this work focuses on short-term problems, with a limited outlook for crosscutting issues, longer-term problems, and more basic research that often portends future solutions. As a result, it is not clear that the sum of individual agency priorities adds up to a truly comprehensive list of national needs and priorities.

There are few areas of research as broadly distributed across the federal government as water resources research, resulting in few examples of how to effectively coordinate large-scale research programs. Nonetheless, the committee identified those factors that encourage or discourage effective coordination of large-scale research programs after hearing about programs for highway research, agricultural research, earthquake and hazard reduction research, and global change research. These factors helped shed light on an effective model for coordination of water resources research, which relies on some entity performing the following functions:

-

doing a regular survey of water resources research using input from federal agency representatives

-

advising OMB and Congress on the content and balance of a long-term national water resources research agenda every three to five years

-

advising OMB and Congress on the adequacy of mission-driven research budgets of the federal agencies

-

advising OMB and Congress on key priorities for fundamental research that could form the core of a competitive grants program

-

engaging in vertical coordination with states, industry, and other stakeholders, which would ultimately help refine the agenda-setting process

The first three activities are intended to make sure that there is a national agenda for water resources research, that it reflects the most recent information on emerging issues, and that the water resources missions of the federal agencies are contributing in some way to national agenda items. A competitive grants program (the fourth activity) is proposed as a mechanism for filling critical gaps in the research portfolio, in the event that certain high-priority research areas are not being adequately addressed by the federal agencies and to increase the proportion of long-term research. This program would require new (but modest) funding. Given the topical gaps noted earlier and in Chapter 4, funding would be needed on the order of $20 million per year for research related to improving the efficiency and effectiveness of water institutions and $50 million per year for research related to challenges and changes in water use.

Three institutional models that could conceivably carry out the bulleted activities listed above are described in Chapter 6. The first model relies on an existing interagency body—the Subcommittee on Water Availability and Quality administered by the Office of Science and Technology Policy. This coordination option is attractive because arrangements are already in place and agency roles and responsibilities are well defined. However, this approach has yet to demonstrate that it can be an effective forum for looking beyond agency missions to fundamental research needs. The second option involves Congress authorizing a neutral third party to perform the functions above, which would place the outside research and user communities on equal footing with federal agency representatives. The independence from the agencies afforded by this option makes it possible to focus the competitive grants program on longer-term research needs, particularly those falling outside agency missions. A disadvantage is that it may engender resentment from the agencies, and OMB may be reluctant to establish such a formal advisory body. A third option is a hybrid model that would be led by OMB and formally tied to the budget process. For more detailed descriptions the reader is referred to Chapter 6, which comprehensively discusses the three options.

Any one of the three coordination options could be made to work in whole or part. Each has strengths and weaknesses (described in detail in Chapter 6) that would need to be weighed against the benefits and costs that could accrue from moving beyond the status quo. In the end, decision makers will choose the coordination mechanism that meets perceived needs at an accept-

able cost in terms of level of effort and funding. It is possible that none of the options is viable in its entirety. However, it may be possible to partially implement an option, which in itself would be an improvement over the status quo. For example, the initiation of a competitive grants program targeted at high-priority but underfunded national priorities in water resources research could occur under any one of the options and in lieu of the other activities listed above.

* * *

Publicly funded research has played a critical role in addressing water resources problems over the last several decades, both for direct problem solving and for achieving a higher level of understanding about water-related phenomena. Research has enabled the nation to increase the productivity of its water resources, and additional research can be expected to increase that productivity even more, which is critical to supporting future population and economic growth. Managing the nation’s water resources in more environmentally sensitive and benign ways is more important than ever, given the recognition now afforded to aquatic ecosystems and their environmental services. A course of action marked by the creation and maintenance of a coordinated, comprehensive, and balanced national water resources research agenda, combined with a regular assessment of the water resources research activities sponsored by the federal agencies, represents the nation’s best chance for dealing effectively with the many water crises sure to mark the 21st century.