4

Status and Evaluation of Water Resources Research in the United States

Establishing a baseline of current research is vital to the task of evaluating whether and how new priorities in water resources research are being addressed. Research is a cumulative enterprise. By necessity, most new research directions will build on existing research infrastructure; other research directions may be established through new research consortia, laboratories, and field sites. Whatever the case, budget initiatives will be cast in terms of departures from the status quo. Unfortunately, the categorization and accounting of water resources research is surprisingly difficult to do under current budgetary procedures. Agencies are not required to report their research to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in standard topical or thematic categories. Further, agencies do not report all their research to OMB. For this reason, the committee gathered budget1 and other data, in the form of a survey, from both federal agencies and nonfederal organizations that fund water resources research. This chapter presents the resulting data and the committee’s analysis of those data, as well as conclusions about the scope of the current investment. The conclusions relate directly to those water resources research priorities expressed in Chapter 3 and in NRC (2001) as being paramount to confronting water problems that will emerge in the next 10–15 years.

SURVEY OF WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH

A necessary part of this study involved collecting budget information from federal agencies and significant nonfederal organizations regarding their recent

expenditures on water resources research. Several methods could potentially be utilized to gather and evaluate such budget information. Ultimately, the committee decided to rely on a format used for over ten years in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Beginning in 1965, the Committee on Water Resources Research (COWRR) of the Federal Council for Science and Technology (FCST), administered out of what was then the President’s Office of Science and Technology, began a yearly accounting of all water resources research conducted by the major federal agencies.2 Budget information, supplied by liaisons from relevant federal agencies, was compiled into ten major categories3 and up to 60 comprehensive subcategories of water resources research. The accounting occurred annually from 1965 to 1975 (except for 1971). The primary goal of COWRR was to facilitate coordination of the various federal research efforts, because it was recognized at that time that water resources research was spread widely throughout the federal enterprise (as it is today). It was also a goal of COWRR to ensure that there was no unnecessary duplication of research efforts, that research was appropriately responsive to current water problems, and that federal resources were available to help solve these problems (COWRR, 1973 and 1974). Nonfederal organizations were not included in the reports.

To compare the current budget information with expenditures on water resources research between 1965 and 1975, the committee adopted the FCCSET model of creating a survey for federal agency liaisons to respond to. The present survey includes most of the same categories and subcategories of water resources research as before, and it encompasses the same waterbodies: fresh, estuarine, and coastal. In January 2003, the survey was submitted to all of the federal agencies that either perform or fund water resources research and to several nonfederal organizations that had annual expenditures of at least $3 million during one of the fiscal years covered by the survey.

The survey consisted of five questions related to water resources research (see Box 4-1). As part of question 1, the liaisons were asked to report total expenditures on research in fiscal years 1999, 2000, and 2001, in order to allow a comparison to the FCCSET survey data of the past. The remaining four questions were posed to help give the committee a better understanding of current and projected future activities of the agencies, and to obtain a qualitative understanding of how research performance is measured. Unlike the data submitted in response to question #1, the answers to the latter questions in the survey are not evaluated in this report in a quantitative fashion.

Responses to the survey were submitted in written form and orally at the third meeting of the NRC committee, held April 29–May 1, 2003, in Washington,

|

BOX 4-1 1a. Please provide budget information for the 11 FCCSET categories for FY1999, FY2000, and FY2001 (as total expenditures, not appropriated funding). A detailed description of each category is attached. b. Please provide an accompanying short (2–3 pages at most) narrative, saying how your programs that encompass water resources research fall into the different FCCSET categories. c. What percentage of these budget numbers were reported to OMB as R&D? (We recognize that there are differences between the OMB definition of R&D and the 11 FCCSET categories.) d. Does your agency conduct research that does not fall into one of the FCCSET categories, but that is considered (by the agency) to be water resources research? Please describe. 2. In no more than 2 pages, provide a summary of your agency’s current strategic plan that governs water resources research. Please include data collection activities. 3. What is being done to coordinate water resources research (1) within your agency, (2) with other agencies, or (3) with external partners (such as the states)? 4. Do you measure progress (i.e., the impact of) in your agency’s water resources research activities? If so, how? (For example, by counting the number of publications, some other metric, etc.) 5. Irrespective of your agency’s mission, what do you think the nation’s water research priorities ought to be?

|

D.C. At that meeting, questions were asked of the liaisons in addition to those listed in Box 4-1 that speak to the different ways that research is conceptualized and conducted within the federal enterprise. These included questions about (1) how the budget information was gathered and the liaison’s confidence in its accuracy, (2) whether the water resources research included in the survey response was conducted internally or externally, and (3) the typical time frame for water resources research within an agency. (Definitions of research relevant to these questions are provided in Box 3-1.) Revised survey responses submitted by the liaisons in June and July 2003 reflected corrections and responses to specific requests from the committee.

The survey requested budget information in 11 major categories (and 71 subcategories) of water resources research. All categories, which are described in detail in Appendix A, closely correspond to categories used in the old FCCSET reports. Nonetheless, some minor changes were made to the old FCCSET categories in order to capture lines of research that were not recognized during the 1960s. Most importantly, new subcategories were added in the areas of global water cycle problems, effects of waterborne pollution on human health, risk perception and communication, other poorly represented social sciences, infrastructure repair and rehabilitation, restoration engineering, and facility protection/ national security. One of the old FCCSET subcategories (VI-C on the ecological impact of water development) was removed from Category VI and was expanded into a new major category (XI) that includes four subcategories on ecosystem and habitat conservation, aquatic ecosystem assessment, effects of climate change, and biogeochemical cycles. This was done in recognition of the increased attention being paid to the water needs of aquatic ecosystems over the last 25 years and a corresponding surge in research in this field. The modified FCCSET categories thus comprehensively describe all areas of research in water resources. It should be noted that the act of data collection, although of paramount importance to water management, is not captured by any of the modified FCCSET categories (Category VII covers research that informs data collection, not data collection itself). This omission on the part of COWRR was intentional, allowing research activities and their budgets to be evaluated independently of monitoring activities. The current survey abides by this separation; that is, the agency liaisons made sure that none of the budget information presented includes pure data collection (e.g., stream gaging, satellite operation, etc.) Nonetheless, given the importance of data collection activities to the water resources research enterprise, Chapter 5 notes recent trends in funding for such activities.

There are obviously limitations inherent in conducting a survey of this nature and in the corresponding results. First and foremost is that the information represents to some degree the best professional judgment of those liaisons that responded. In almost all cases, federal agency programs in water resources research are not organized along the modified FCCSET categories. Undoubtedly, there were cases where a program logically fell into more than one category. In

such cases, the liaisons were asked to give their best judgment of the most relevant category. In addition, variable sources of information were used by the liaisons (in terms of personnel and databases consulted), and the liaisons may have interpreted the survey differently from one another. These factors are reflected by a certain degree of error in the individual budget numbers submitted by the liaisons. However, after questioning the liaisons about their confidence in the submitted information, the committee feels that the magnitude of this error is small when compared to the broad trends that are discerned by the analysis below. Furthermore, the trend analysis is accompanied by a quantitative assessment of uncertainty, which was taken into account during the committee’s evaluation of the data.

Second, the possibility exists that the committee did not capture all of the relevant federal and nonfederal organizations involved in water resources research, either because these organizations were not approached by the committee or because they chose not to participate. With respect to the federal agencies, the committee is confident that all of the major agencies funding or conducting water resources research within the United States were contacted and that the submitted survey responses represent the vast majority of the federal investment in water resources research. There is less certainty about the nonfederal organizations. The major not-for-profit organizations involved in water resources research were contacted, as well as the largest (in terms of funding) of the state Water Resources Research Institutes (in order to reflect state funds spent on relevant research). Nonetheless, it is recognized later in this chapter that the accounting of significant nonfederal organizations’ funding of water resources research may be an underestimate, both in terms of total dollars and represented subcategories.

A related issue for those federal agencies that responded to the survey is that not all of their relevant research funds were reported, especially where certain programs are not characterized as research in their congressional authorization. For example, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) site characterization work in the Yucca Mountain Program (see Chapter 3) is at the cutting edge of hydrogeology, but it is not classified as research for budgetary purposes. [In contrast, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) does classify its Yucca Mountain work as research.] Because the agencies would be reluctant to report these types of expenditures, it was not possible for the committee to assess their magnitude or importance. This is also a concern for agencies that conduct extensive place-based studies, most of which are managed separately from the general water resources research program, are not reported to OMB as research, and thus are difficult to account for. Examples include the Florida Everglades restoration—jointly run by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), the Department of the Interior, and the South Florida Water Management District—and CALFED, which is a San Francisco Bay Delta restoration program involving multiple federal and state agencies. For those federal agencies that were identified at the April 2003 committee meeting as funding substantial place-based research, the committee requested that their two largest projects be included in their final response to the survey. These inclu-

sions are reflected in revised survey responses from the Corps and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Nonetheless, not all place-based research from these two agencies could be captured, and no place-based information was collected from other agencies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the other major federal agency thought to have an investment in place-based research. This may also lead to an underestimate in the reported water resources research funding.

Third, the survey covers only fiscal years 1999, 2000, and 2001. Three years of data were felt to be of sufficient quantity to allow the committee to assess the nation’s investment without creating a burdensome task for the liaisons. In addition, vastly differing economic climates prevailed during these years, which may be reflected in the survey responses and may thus enable the committee to observe short-term variability in research expenditures. Clearly, however, these three years of data represent only a snapshot in time. Thus, although there is a trends analysis in this chapter, no assumptions should be made regarding funds spent between 1975 and 1999.4 The current request for information did not cover FY2002 or FY2003 because it was felt that at the time the survey was submitted, the agencies would not be able to provide accurate estimates of total expenditures for those years. Thus, events subsequent to FY2001 that may have impacted research spending (e.g., increased attention to national security) are not reflected in the survey.

Finally, the varying scope of the modified FCCSET categories must be acknowledged. In an attempt to keep the number of subcategories reasonable, some of them broadly lump together what may be, in academic circles, disparate research issues. For example, there is only a single subcategory (VI-H) to capture all water resources research conducted in areas of sociology, anthropology, geography, political science, and psychology. Other subcategories are much more narrowly focused. This diversity, to a certain extent, reflects the fact that some subcategories have a stronger historical linkage to water resources research per se. In general, in those areas where the majority of funds are being spent, the committee tried to maintain or create a larger number of subcategories so that specific trends in funding could be discerned.

For the purposes of the discussion below, the budget numbers from all years were converted into FY2000 constant dollars prior to graph preparation and data analysis.

OLD FCCSET DATA

From 1965 until 1975, data on water resources research funds were collected from the following federal agencies: U.S. Departments of Agriculture, Commerce,

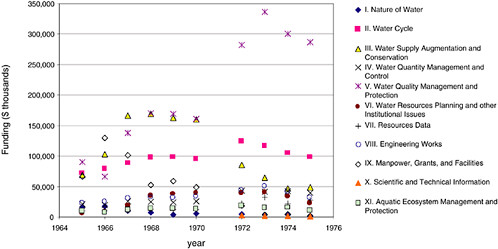

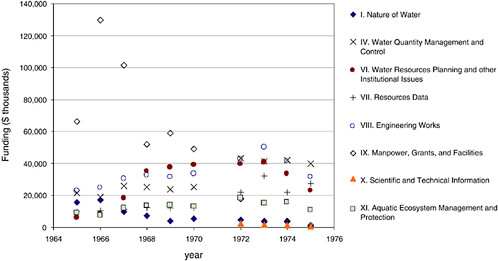

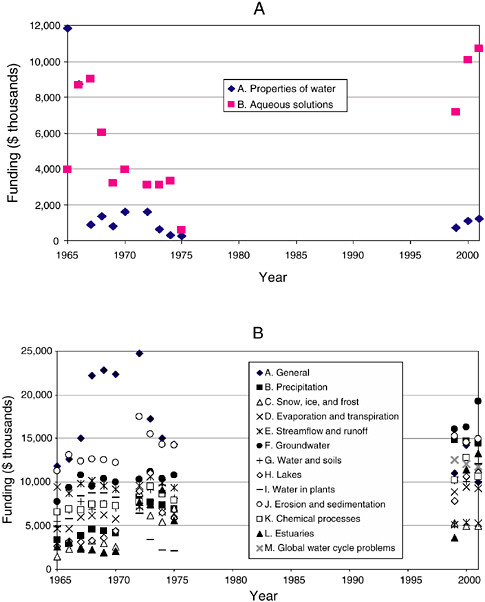

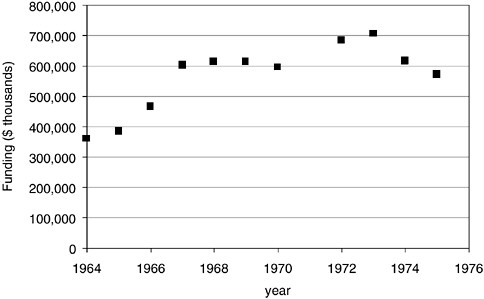

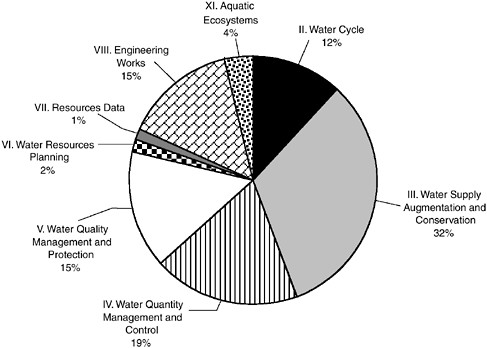

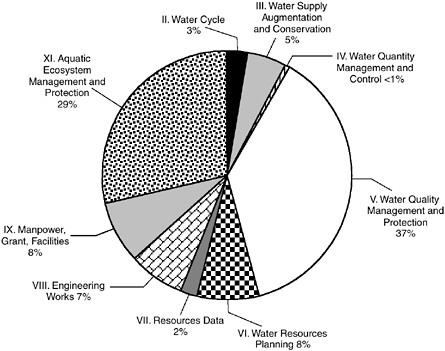

Defense, the Interior, and Transportation; EPA (from 1973 on); the National Science Foundation (NSF); the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (from 1966 on); and other smaller agencies such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, Housing and Urban Development, the Atomic Energy Commission, and the Smithsonian Institute. The budget data are presented in a series of annual reports from COWRR and are summarized in COWRR (1973 & 1974). FCCSET data show a steady increase in funding for water resources research between 1964 and 1967, a leveling off from 1967 to 1973, and a slight decrease from 1973 to 1975 (see Figure 4-1). A more in-depth examination reveals that the vast majority of these funds were spent in a few FCCSET categories, and these disparities increased during the examined period. Thus, for example, in 1965, Categories II (water cycle), III (water supply augmentation and conservation), and V (water quality management and protection) constituted over 60 percent of all water resources research, while in 1975, these same categories comprised 76 percent of the total. As shown in Figure 4-2, this increase is attributable to a large increase in spending on water quality management and protection (Category V).

The only FCCSET category that showed positive growth during this ten-year period was V (water quality management and protection), and even this category began to decline after 1973. Most of the other major categories showed relatively stagnant funding during the period, including II (water cycle), IV (water quantity management and control), VII (resources data), X (scientific and technical infor-

FIGURE 4-1 Total expenditures on water resources research, 1964–1975. Values reported are constant FY2000 dollars. SOURCES: COWRR (1973 & 1974).

mation), and XI (aquatic ecosystem management and protection). Consistently negative trends in funding were observed for Categories I (the nature of water) and IX (manpower, grants, and facilities). For Categories III (water supply augmentation and conservation), VI (water resources planning), and VIII (engineering works), an initial increase observed in the late 1960s was followed by a substantial decrease in the early 1970s, in the case of Category III to levels below the 1965 level (primarily because of a drop in funding for desalination research). Trends for the “smaller” major categories, which are difficult to discern in Figure 4-2, are presented in Figure 4-3.

The reasons for the observed trends likely include an initial interest on the part of Congress and various administrations to increase research spending in the late 1950s and early 1960s, followed by a retraction in the wake of better understanding environmental processes and the resulting competition between environmental water needs and economic growth. As discussed in Chapter 2, the early 1970s saw the federal government transform from an ardent supporter of water resources projects to the primary regulator of industries responsible for declines in water quality. This may also account for the disproportionate support for water quality research (Category V) compared to other areas of research. That is, greater investment in Category V was seen as essential to meeting various water quality standards in the nation’s lakes and rivers, as mandated by the newly minted Clean Water and Safe Drinking Water Acts. Furthermore, in many states, impairment in water quality loomed as a more important constraint on the development of water resources than the issue of supply. In addition, throughout the 1970s, media reports focused on water quality issues, giving them the political prominence that has helped to drive the distribution of research funding shown in Figure 4-2. The topically skewed nature of water resources research in the middle 1970s has been noted in other studies, in particular a FCCSET report that recommended reducing the relative proportion of funding going to Category V, while also calling for overall increases in the total water resources research budget (COWRR, 1977).

WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH FROM 1965 TO 2001

To observe trends in water resources research funding, the FCCSET accounting of 1965–1975 was repeated by requesting budget information from 19 federal agencies known to support water resources research. Table 4-1 lists the federal agencies queried during the first survey period and during this study. A similar request was made of several nonfederal organizations, of which the following were deemed to be making significant contributions to water resources research over the period in question (FY1999–FY2001): the American Water Works Association Research Foundation (AWWARF), the Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF), the Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the four largest Water Resources Research Institutes (Nevada, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah). For both

TABLE 4-1 Federal Agency Participation in Surveys on Water Resources Research Funding

|

Agency |

Initial FCCSET period (1965–1975) |

Current Survey (FY1999–FY2001) |

|

Agriculture |

||

|

ARS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

CSREES |

Yes |

Yes |

|

ERS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

FS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Commerce |

||

|

NOAA (many programs) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Defense |

||

|

Corps |

Yes |

Yes |

|

ONR |

No |

Yes |

|

SERDP/ESTCP |

No |

Yes |

|

Energy |

No |

Yes |

|

Health and Human Services |

No |

|

|

ATSDR |

|

Yes |

|

NCI |

|

Yes |

|

NIEHS |

|

Yes |

|

Interior |

||

|

USGS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

USBR |

Yes |

Yes |

|

FWS |

Yes |

No |

|

OWRR |

Yes |

No longer in existence |

|

Transportation |

Yes (1966–1971) |

No |

|

FHA |

Yes (1973–1975) |

|

|

Coast Guard |

Yes (1973–1975) |

|

|

EPA |

Yes (1973–1975) |

Yes |

|

NASA |

Yes |

Yes |

|

NSF |

Yes |

Yes |

|

AECa |

Yes |

No longer in existence |

|

TVA |

Yes |

No |

|

Smithsonian |

Yes (1968–1975) |

No |

|

HUD |

Yes (1967–1975) |

No |

|

aThe functions of the Atomic Energy Commission were subsumed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission via the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 and by DOE. Note: The National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Tennessee Valley Authority were contacted but chose not to participate in the current survey. |

||

the federal agencies and the nonfederal organizations, the budget information submitted was total expenditures (and not appropriated funds). In addition, all third-party funding was excluded from the budget numbers, as was funding for pure data collection, education, and extension activities. For the federal agencies, almost all of the funds included in the survey are reported to OMB as research and development funds. Survey data from both federal and nonfederal agencies are summarized and presented graphically throughout the chapter, with detailed information available in Appendix B.

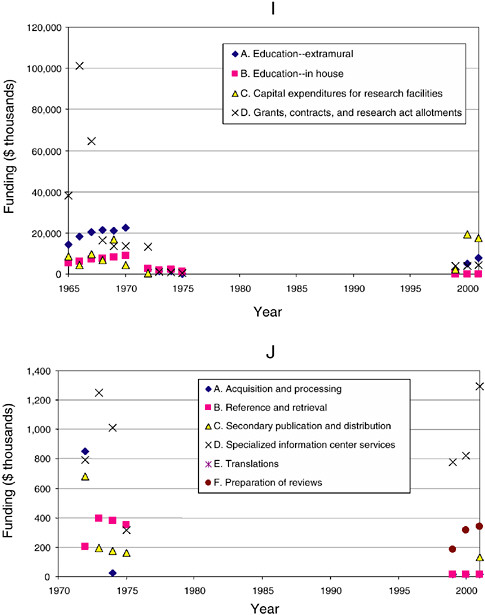

Total Federal Agency Support of Water Resources Research

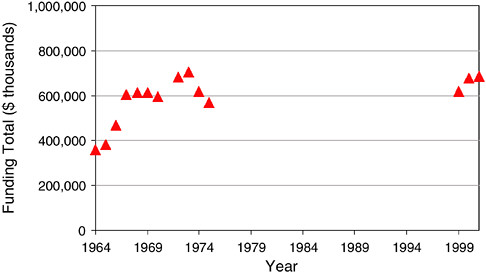

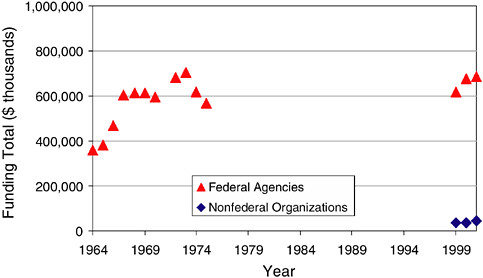

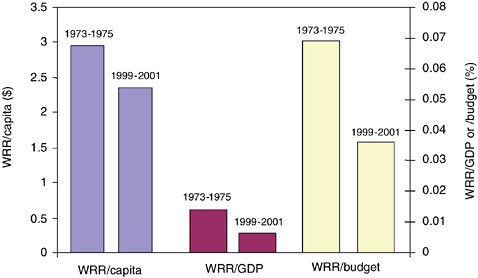

The total federal funding for water resources research from 1964 to 1975 and for 1999, 2000, and 2001 is shown in Figure 4-4. Annual expenditures on water resources research have remained static near the $700 million mark since 1973, after having doubled between 1964 and 1973. A quantitative analysis was conducted to discern whether there is a significant difference in total funding between the average 1973–1975 levels and the average 1999–2001 levels. In order to do this analysis (which is explained in detail in Appendix C), it was assumed that the annual data contain measurement errors that are independent from year to year, that the distribution of errors in averages of annual values can be well approximated by a normal distribution, that the standard deviation of the errors in averages of annual values ranges in all cases from 25 percent to 50 percent of the

FIGURE 4-4 Total expenditures on water resources research by federal agencies, 1964–2001. Values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

average, and that there are no significant systematic biases in the annual funding data. As shown in Table 4-2, there is small likelihood that the averages for these two time periods are different under the conditions of uncertainty stated above. This supports the statement that funding levels for water resources research have not changed significantly since the early 1970s.

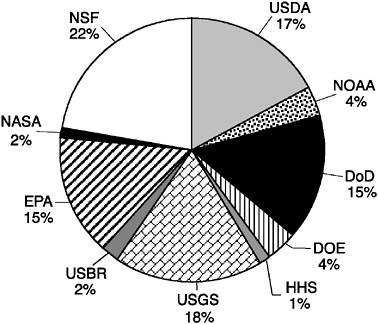

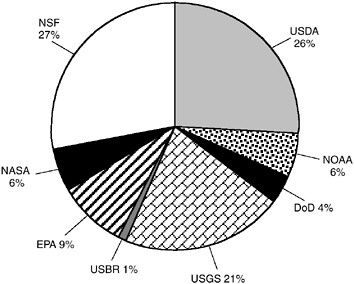

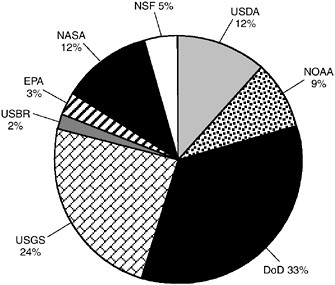

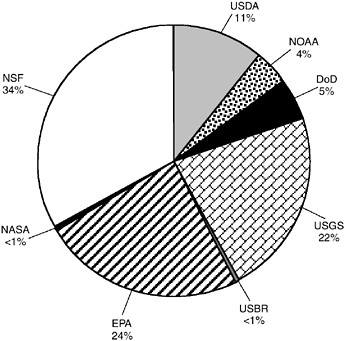

Figure 4-5 shows how the $700 million was distributed among the federal agencies in FY2000. Notably, no agency contributed more than 25 percent of the total funding, with five agencies (USDA, USGS, NSF, DoD, and EPA) accounting for nearly 88 percent of the total funding. The smaller five agencies (DHHS, USBR, NOAA, DOE, and NASA) together contributed 12.3 percent of the reported total. This speaks to the broad impact of, and interest in, water-related issues across the federal government. Funding trends from 1965 to 2001 for the 11 major categories and their subcategories are shown in Figures 4-6 and 4-7,

TABLE 4-2 Likelihood of a Significant Increase or Decrease in Funding from the 1973–1975 Time Period to the 1999–2001 Time Period (see Appendix C for methods)

|

FCCSET Category |

Likelihood at the 25 percent uncertainty level (%) |

Likelihood at the 50 percent uncertainty level (%) |

Increase or Decrease* |

|

I. Nature of Water |

99.9 |

92.6 |

Large increase |

|

II. Water Cycle |

79.3 |

66.1 |

Increase |

|

III. Water Supply Augmentation |

0.2 |

7.5 |

Large decrease |

|

IV. Water Quantity |

59.3 |

55.1 |

No change |

|

V. Water Quality |

12.0 |

28.0 |

Large decrease |

|

VI. Water Resources Planning |

0.2 |

7.5 |

Large decrease |

|

VII. Resources Data |

0.5 |

9.8 |

Large decrease |

|

VIII. Engineering Works |

66.6 |

57.9 |

Slight Increase |

|

IX. Manpower, Grants, Facilities |

100.0 |

95.0 |

Large increase |

|

X. Scientific and Technical Info |

45.2 |

46.8 |

Slight decrease |

|

XI. Aquatic Ecosystems |

100.0 |

96.7 |

Large increase |

|

Total Water Resources Research |

55.1 |

52.5 |

No change |

|

Total Water Resources Research minus Category XI |

28.5 |

38.9 |

Decrease |

|

*Values above 50 indicate a significant increase from the mid 1970s to the late 1990s. Values less than 50 indicate a significant decrease. Values around 50 percent indicate no significant increase or decrease. |

|||

FIGURE 4-5 Federal agency contributions as a percentage of the total funding for water resources research in 2000.

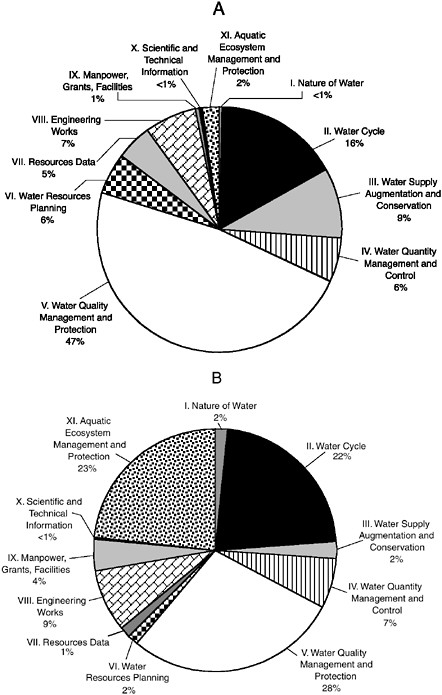

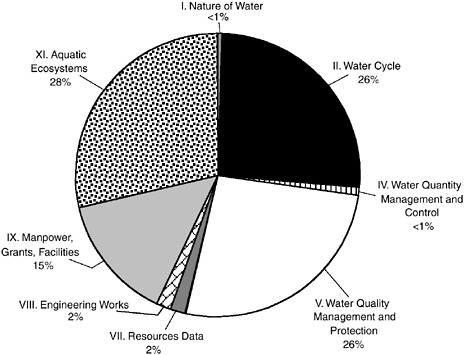

respectively. Note that all three years of data (1999, 2000, and 2001) were used in the trends analysis to follow. However, for the purposes of presentation, the pie charts in this chapter show only data from 2000 (which is generally representative of data from 1999 and 2001).

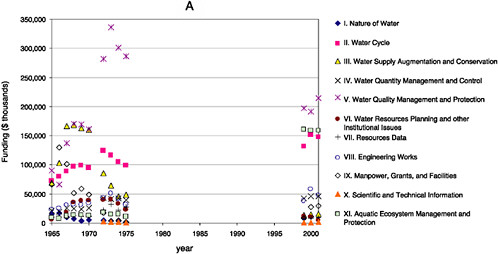

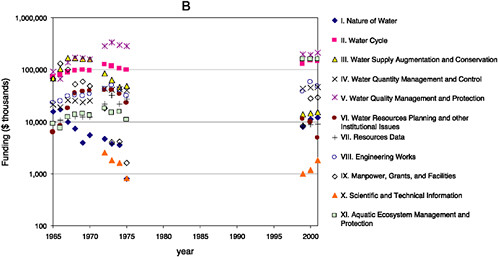

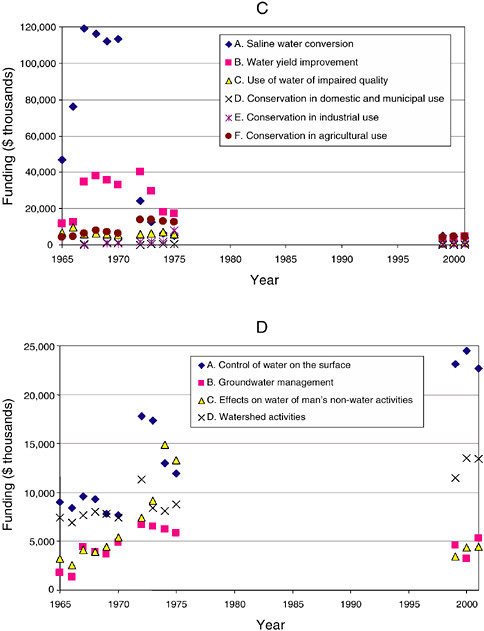

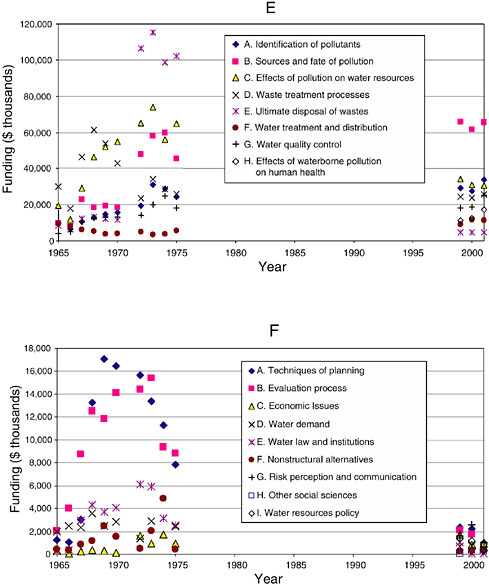

Several conclusions can be drawn from these graphs. With respect to the trends over time for the individual major categories, most funding levels have remained stable or have declined since the mid 1970s—a conclusion supported by the comprehensive uncertainty analysis presented in Table 4-2 and in Appendix C. Category V (water quality), in particular, declined from 1975 to 2000 both in real terms (from $286 million to $192 million) and as a percentage of total funding (from 50 percent to 28 percent). For this category, it can be stated with high confidence that the mid 1970s funding is higher than the late 1990s funding. Even more dramatic declines are observed for Category III (water supply augmentation), which declined from a high of $64 million in 1973 to $14 million in 2000; Category VI (water resources planning and institutional issues), which declined from a high of $41 million in 1973 to $9.8 million in 2000; and Category VII (resources data), which declined from a high of $32 million in 1973 to $8.7 million in 2000. In these three cases, there is very high likelihood that the mid 1970s

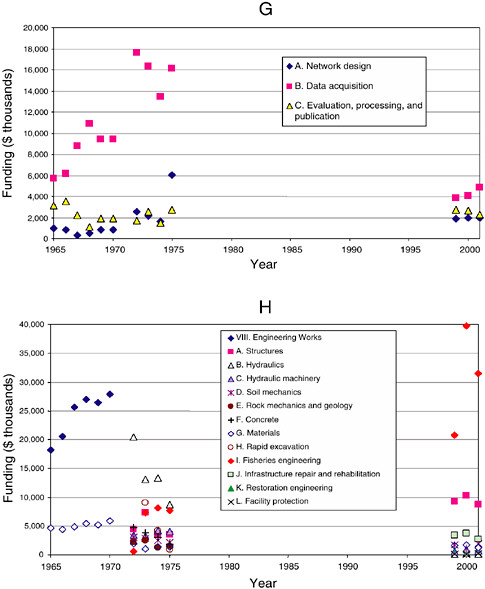

FIGURE 4-7 (E) and (F) Federal agency funding in FCCSET subcategories of Categories V (water quality management and protection) and VI (water resources planning and other institutional issues), 1965–2001. Subcategories V-H, VI-G, VI-H, and VI-I are new to the recent survey. Values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

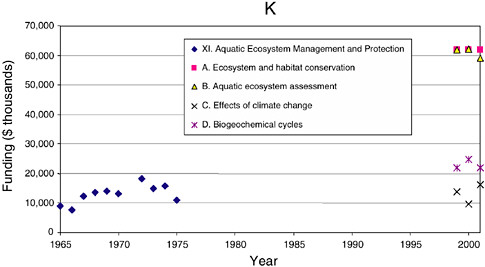

FIGURE 4-7 (G) and (H) Federal agency funding in FCCSET subcategories of Categories VII (resources data) and VIII (engineering works), 1965–2001. Subcategories VIII-B through VIII-I (except VIII-G) were created in 1972 to further define “engineering works.” Subcategories VIII-J, -K, and -L are new to the recent survey. Values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

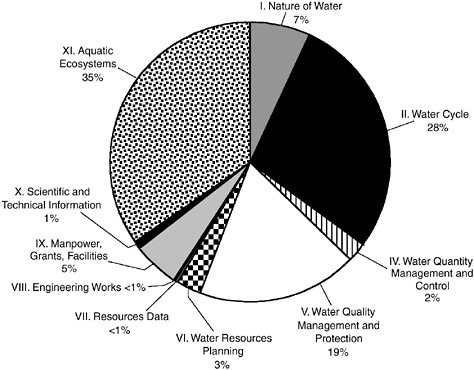

FIGURE 4-7 (K) Federal agency funding in the FCCSET subcategories of Category XI (aquatic ecosystem management and protection), 1965–2001. Note that the four subcategories were created for the recent survey. All relevant research in these four areas was previously recorded in one subcategory (denoted by the black diamond). Values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

level funding is higher than the late 1990s level, for both cases of uncertainty depicted (that is, where uncertainty is either 25 percent or 50 percent of the mean values). Thus, funding has declined substantially in the late 1990s with respect to the mid 1970s for these four major categories.

Funding in five of the major categories (I—nature of water, IV—water quantity, VIII—engineering works, IX—manpower and grants, X—scientific and technical information) appears from the figures above to be more or less comparable to that recorded 30 years ago. However, when looking quantitatively at the difference between the 1973–1975 and 1999–2001 time periods, some minor trends emerge. In the case of Categories I and IX, there have been significant increases from the mid 1970s to the present. For Category X, one can state with high confidence that funding has decreased since the mid 1970s. And for Categories IV and VIII, there are no significant differences between the funding levels of the two time periods, particularly when it is assumed that uncertainty is equal in value to 50 percent of the mean.

There have been very modest increases in funding for Category II (water cycle) over the entire 30-year period, and the uncertainty analysis in Appendix C supports a high likelihood for an increase in funding from the mid 1970s to the present. However, it is in Category XI where the greatest increases are observed.

Funding for aquatic ecosystem management and protection jumped from $15 million in 1973 to $158 million in 2000 (23 percent of the total water resources research funding that year). This partly reflects the lack of a well-defined category for aquatic ecosystem research during the time of the 1965–1975 FCCSET survey. More important, however, is that concern for aquatic ecosystem management and protection grew enormously following the transformative events that sparked the landmark environmental legislation of the 1960s and 1970s including the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (see Chapter 2). Several decades later, biological diversity and ecosystem processes of lakes, wetlands, and rivers are increasingly at risk, raising concerns for potential degradation of ecosystem goods and services and loss of species. While many of these problems have a long history, most prior research focused on a narrow view of water quality for human use and direct harm to sensitive species. As a consequence of the recent recognition for the need for whole ecosystem research, including studies of long duration and large spatial scale, research expenditures in Category XI have increased greatly. The four distinct subcategories of research into the protection and management of aquatic ecosystems constitute a suite of research activities that were largely absent from the nation’s water resources research or were thought of more in the context of water quality research in the 1960s.

It is interesting to note that the trends for the individual subcategories do not always mirror the trend of their major category. For example, although funding for water quality studies (V) declined overall from the mid 1970s to the present, two subcategories within Category V saw modest funding increases—the identification of pollutants (V-A) and understanding the sources and fate of pollutants (V-B).

As far as balance among the 11 major categories, the situation in 2000 has shifted to encompass far more aquatic ecosystems research than in 1973 (see Figure 4-8). Much of this has come at the expense of funding for Categories III (water supply) and V (water quality). In general, however, there is greater parity among the major categories of water resources research in 2000 than there was in 1973.

Federal Agency Budget Breakdown

A complementary way of presenting the data is to consider how individual federal agencies distributed their expenditures among the 11 major modified FCCSET categories. Although many of the individual offices that reported conducting and funding water resources research from 1965 to 1975 have changed (see Table 4-1), most of the cabinet-level federal agencies involved in supporting water resources research in the mid 1960s are still major players in this enterprise today.

Individual agencies have distinct missions and responsibilities, and they differ in their mandated emphasis on fundamental vs. applied research. These

agencies’ total budgets and the distribution of their research funding exhibit considerable differences as well. In addition to considering the specific distribution of funding by agency and category, the following section briefly reviews the research focus of each agency. (Although the agencies are listed alphabetically in Tables 4-1, 4-3, and 4-4, the following narratives are ordered by the size of the agencies’ funding for water resources research.)

National Science Foundation

Since its inception in 1950, the NSF has awarded grants and contracts that support and strengthen science and engineering research and education, and it plays a significant role in supporting the research infrastructure of the nation’s universities, including support of equipment, student fellowships, individual researchers, and multidisciplinary research teams. Although both basic and applied research efforts are included, the NSF has long been considered a primary, if not the primary, agency supporting curiosity-driven research at academic institutions and nonprofit organizations to address fundamental issues. Although much of the benefit to society of this research is expected to accrue over long periods, some benefits occur in a short time frame.

Water-related research is found in nearly all NSF organizational units as well as in crosscutting initiatives such as the Water and Carbon Cycle initiatives, but there is no single program for water resources research. Research supported by the Directorate for Biological Sciences is relevant to the categories of aquatic ecosystems (XI) and the water cycle (II), and it encompasses a network of Long-Term Ecological Research sites (some of which have an aquatic component). The Directorate for Engineering supports research into water and wastewater treatment; the fate, transport, and modeling of contaminants; and sensors and sensor networks for water quality measurement. The Directorate of Geosciences supports traditional hydrologic science, hydrologic–ecological interactions, and meteorological and climate studies related to the water cycle ranging from precipitation processes to long-term trends in water characteristics. The Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences funds water-related research in chemistry and mathematics, including fundamental properties of water and ice, fate and transport of chemicals in water, and mathematical modeling of the water cycle. The Directorate for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences funds a variety of projects that explore fundamental social, economic, cultural, geographic, or decision-related aspects of human activity related to water resources and facilitates international research linkages and experiences for students and investigators. The Office of Polar Programs supports research on aquatic ecosystems in Arctic regions and Antarctica. The Directorate for Education and Human Resources provides funding for water-related education projects across the full range of directorate programs. Support areas include teacher preparation, curriculum development, informal education projects, and digital library resources. NSF also

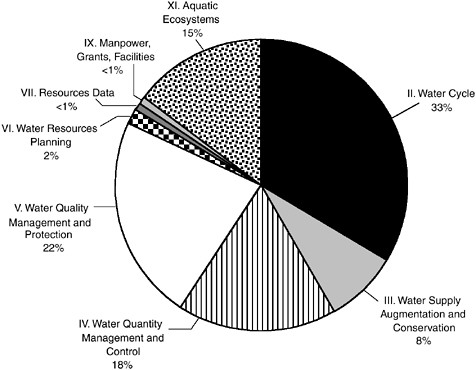

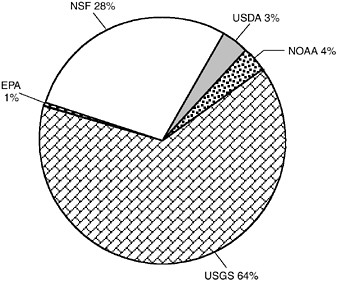

FIGURE 4-9 National Science Foundation FY2000 expenditures by major category ($150,892,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

supports Science and Technology Centers to address water purification, water resources management in semiarid climates, and river processes.

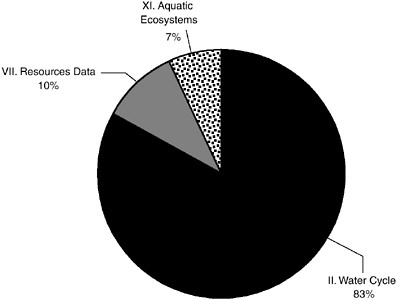

In FY2000, NSF accounted for 22 percent of total federal water resources research expenditures, four-fifths of which was allocated to categories XI (aquatic ecosystems), II (water cycle), and V (water quality), as shown in Figure 4-9. These results are expected, since these categories deal more with fundamental water processes than with water-related operations, data collection, or administration. In addition, NSF has focused its water resources research on the natural rather than the social sciences, accounting for the low percentage of funds spent in category VI (water resources planning and other institutional issues).

U.S. Geological Survey

Created in 1879, the USGS has evolved from being an agency that performs “surveys” of the nation’s land, mineral, and water resources to one that encompasses a broader view of earth science. Its current mission is to provide reliable

scientific information to describe and understand the earth; minimize loss of life and property from natural disasters; manage water, biological, energy, and mineral resources; and enhance and protect our quality of life (USGS, 2002). The USGS today is organized into four major disciplines. The Biological Resources Discipline—added to the USGS in 1995—focuses on status and trends of natural systems, basic ecological understanding, analysis of threats, and application of knowledge to management and stewardship. In the past, the Geology Discipline has focused on fundamental geological processes, hazard assessment, and energy and minerals. Its portfolio today includes water-related topics, including the environmental impacts of climate variability, the geological framework for ecosystem structure and function, and geological controls on groundwater resources and hazardous waste isolation. The Geography Discipline is responsible for building, maintaining, and applying The National Map. The discipline leads in partnerships with state and local governments and the private sector in producing state-of-the-art geographic tools and products, such as topographic, geological, and hydrographic maps of the entire nation.

The mission of the Water Resources Discipline (WRD) is to “provide reliable, impartial, timely information that is needed to understand the Nation’s water resources” (USGS, 2004). As such, USGS scientists conduct research on a wide array of issues central to human and environmental health, including drinking water quantity and quality, impacts of population growth, urbanization and other land-use changes, suitability of aquatic habitat for biota, hydrologic hazards, climate, surface water and groundwater interactions, and hydrologic system management. The WRD maintains a long-term data collection program to collect, manage, and provide scientifically based information that describes the quantity and quality of waters in the nation’s streams, lakes, reservoirs, and aquifers. Prime examples include the network of stream gages, the National Stream Quality Accounting Network (NASQAN) program, the Hydrologic Benchmark Network program, and the groundwater-level network. Communication of data and information is a priority of all USGS disciplines. Data collected by the USGS as part of its monitoring activities are widely used by a variety of agencies responsible for water and environmental management and by businesses, citizens, and researchers in government, academia, and the private sector. Trends in funding for data collection per se are discussed in Chapter 5.

With one programmatic exception, all water-related research is conducted in-house by USGS scientists. USGS has several types of programs for conducting research: a centrally coordinated National Research Program in the hydrologic sciences; distributed research investigations, including district offices, the National Water Quality Laboratory Methods Group, portions of the National Water Quality Assessment Program (NAWQA), the Yucca Mountain Project, and the Cascades Volcano Observatory; and programs that are primarily focused on the geology or biology disciplines. About 25 percent of USGS funding for water-related research is managed through the National Research Program. The

USGS manages one external water research program, which is the state Water Resources Research Institutes.

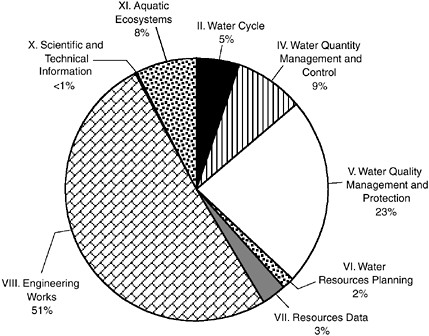

USGS, which contributed 18 percent of the total research budget in FY2000, distributed 80 percent of those funds primarily in Categories XI (aquatic ecosystem management and protection), II (water cycle), and V (water quality management and protection) (see Figure 4-10). Within those three categories, funds were distributed evenly among most subcategories. Aquatic ecosystems research is a growing area of emphasis and is conducted within the Biological Resources and Water Resources disciplines. USGS research supports federal resource management needs in the Everglades, the San Francisco Bay-Delta, the Snake and Columbia river systems, and other systems. Fundamental research on the water cycle and water quality is led by the Water Resources Discipline. The Survey’s research on the water cycle has provided a critical foundation for domestic and international hydrologic and energy balance studies related to regional water management and flood control, as well as for understanding the longer-term implications of climate change. Research on all aspects of water

FIGURE 4-10 U.S. Geological Survey FY2000 expenditures by major category ($123,108,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

quality is driven by priorities and problems identified by state and local partners, the NAWQA program (initiated in 1991), and programs related to toxic chemical and aquatic ecosystem function. Category IX (manpower, grants, facilities) accounted for 15 percent of USGS expenditures, the majority of which supported water research facility infrastructure such as the Hydrologic Instrumentation Facility. Some of these funds, authorized by the Water Resources Research Act of 1965 as amended, provide for research, education, and information exchange with the 54 state Water Resources Research Institutes. In addition, a small part of that program ($1 million) supports a competitive grants program at academic institutions to address high-priority water issues.

U.S. Department of Agriculture

The USDA supports water-related research with four major agencies. The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is the principal in-house research agency for USDA and contributes around two-thirds of the USDA funding for water resources research. Its research agenda is organized under 22 national programs, one of which is Water Quality and Management, which supports three main programs relevant to the nation’s agricultural water resources. The first of these three programs, agricultural watershed management, includes research on water supply and use on irrigated and rain-fed lands to optimize water use and resolve competing demands through establishment of science-based technologies and management. Irrigation and drainage management research, the second program, is intended to support efficiency and sustainability in the face of anticipated declines in water availability. Third, water quality protection and management research emphasizes reducing water contamination from agricultural lands. ARS research is conducted at nine research centers and 83 research locations situated throughout the nation. The missions of several of the research locations including the USDA Water Conservation Lab in Phoenix, Arizona, and the USDA Salinity Lab at Riverside, California, address water and water-related topics. Although most of its research is done by USDA scientists (some of whom hold faculty positions), ARS further involves university faculty in research projects through partnerships and cooperative agreements. Although much of the ARS research is applied (to agricultural problems), there is also a significant component of basic research.

The Cooperative State Research Education and Extension Service (CSREES) provides about 20 percent of the USDA’s funding for water resources research. Its primary functions are to identify, develop, and manage programs to support university-based and other institutional research, education, and extension in order to advance knowledge for agriculture, the environment, human health and well-being, and communities. The majority of research functions of CSREES are carried out by faculty at the nation’s land grant colleges and universities. In addition to providing core research support for these faculty, CSREES operates a number of annual, extramural research competitions that pertain to the effects of

agricultural practices on aquatic ecosystems and watersheds, including nonpoint source nutrients and other contaminants. CSREES activities fall into three program areas: (1) the National Research Initiative, (2) the Hatch Act, and (3) the 406 National Integrated Water Quality Program. Most of the research focuses on water and watershed issues as they relate to agriculture and the conservation of agricultural resources.

The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) has contributed about 18 percent of the USDA funding for water resources research in recent years. It maintains an inhouse staff of researchers, including forest hydrologists, fisheries scientists, aquatic ecologists, and climate researchers, to support its management of 155 national forests and 20 national grasslands and to provide outreach to managers of state and private lands. Research units are organized into eight regional research stations, and many of the scientists at the research stations hold academic appointments at nearby universities. USFS scientists cooperate extensively with colleagues from universities and other agencies engaged in forestry and related research and in integrated studies such as the six Long-Term Ecological Research studies that are focused on USFS experimental watersheds. Thus, the research programs of the USFS are closely integrated with and related to the programs of research carried out by faculties at the schools and colleges of forestry. The USFS maintains a broad disciplinary orientation among its research staff, including hydrology, fisheries, aquatic ecology, climatology, engineering, and economics. Research focuses include watershed management, aquatic–terrestrial interactions, fisheries, water quality, and ecology. There are extensive programs of research on watershed management that address issues related to water yields and the maintenance of water quality from forest and range lands. Although much of the USFS research is applied research directed to problems of managing forests and grasslands, the USFS also devotes a substantial effort to investigate basic, long-term questions.

The Economic Research Service (ERS) provides economic analysis relevant to support a competitive agricultural system as well as promote harmony between agriculture and the environment. The general areas of research include the economics and policy dimensions related to agriculture, food, natural resources, and rural development. In the water domain, the agency provides survey-based information on irrigation and water use for agriculture. The ERS economic research program informs USDA policy and program decisions affecting water quality and wetland preservation, and it also derives economic implications of proposed or alternative water quality regulations for the food, agricultural, and rural sectors. The research activities of ERS also address institutional issues such as those related to water transfers and water markets and institutional responses to drought and water scarcity. All of this research is conducted by an internal staff of economists and social scientists, because this agency makes few extramural grants outside of its food, nutrition, and invasive species management program areas. This is the only federal agency having an interest in water research that focuses exclu-

sively on economic and institutional issues, and it constitutes less than 1 percent of the USDA funding total for water resources research.

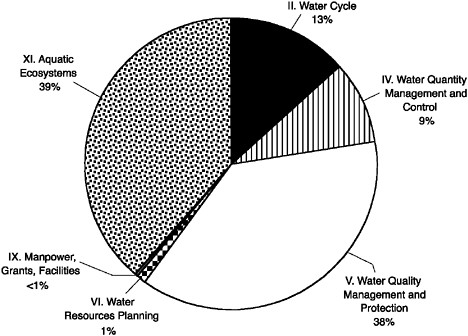

In FY2000, these agencies within USDA accounted for 17 percent of total federal water resources research expenditures. Research into the water cycle (II), mainly under ARS, accounts for one-third of USDA water-related research, and this research appears to be distributed across multiple aspects of the water cycle in an agricultural context. Water quality management and protection (V), supported by ARS and CSREES, is the next-largest category and includes research aimed at water quality control, pollutant source and fate, and waste disposal. All of the agencies with the exception of ERS support research on water quantity management and control (IV), due to the importance of agriculture in influencing runoff and other watershed processes. Aquatic ecosystem research (XI) at USDA derives almost exclusively from the fisheries research done by the USFS. Water supply augmentation and conservation (III) supported by ARS includes research primarily into water yield improvement and agricultural water use conservation. Together these five categories make up virtually all USDA water-related research expenditures, as shown in Figure 4-11.

FIGURE 4-11 Department of Agriculture FY2000 expenditures by major category ($116,126,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

U.S. Department of Defense

About 80 percent of Department of Defense (DoD) funding for water resources research is contributed by the Corps, with lesser amounts coming from the Office of Naval Research (ONR) (about 2 percent) and the Strategic Environmental Research and Development and Environmental Security Technology Certification Programs (SERDP/ESTCP) (about 18 percent). Programmatic areas for the Corps include navigation systems, flood and coastal protection, environmental technologies, infrastructure engineering, geospatial technologies, and integrated technologies for decision making. The mission of the Corps is largely operational in nature, and thus most of the research is highly applied. Its regulatory responsibilities are generally limited to specific provisions of the Clean Water Act, particularly with respect to managing and regulating wetlands. Engineering works, hydraulic modeling, soil mechanics, and contaminated dredge materials are some major research focuses, with the majority of Corps activity being based at seven research laboratories around the nation. In-house research is conducted at seven research laboratories (Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory, Geotechnical and Structures Laboratory, Information Technology Laboratory, and Environmental Laboratory, all in Vicksburg, MS; Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, Hanover, NH; Construction Engineering Research Laboratory, Champaign, IL; Topographic Engineering Center, Alexandria, VA) or at the Institute for Water Resources at Fort Belvoir, VA, and its Hydrologic Engineering Center at Davis, CA.

ONR coordinates, executes, and promotes the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps through grants to schools, universities, government laboratories, and nonprofit and for-profit organizations. It provides technical advice to the Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of the Navy and works with industry to improve technology manufacturing processes. SERDP/ ESTCP carries out research to reduce costs and environmental risks by developing cleanup, compliance, conservation, and pollution prevention technologies. In addition, SERDP/ESTCP funds research on cleanup of contaminated defense sites, DoD compliance with environmental laws and regulations, and measures to reduce defense waste streams.

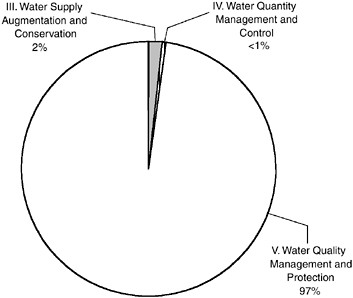

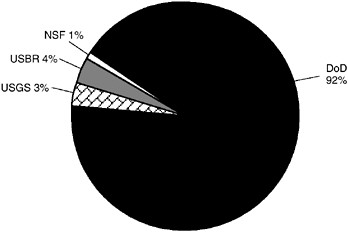

DoD activities account for 15 percent of the overall federal total for water resources research. As shown in Figure 4-12, about half of DoD funds are spent in Category VIII (engineering works), which is anticipated to be necessary to support the Corps’ large operational mission, and about a fourth of the funds are spent in Category V (water quality management and protection), which is where almost all SERDP/ESTCP and ONR funds are devoted.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

As mentioned in Chapter 2, the EPA was created in 1970 to carry out broad responsibilities for both regulation and research, with an emphasis on protecting

FIGURE 4-12 Department of Defense FY2000 expenditures by major category ($104,668,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

human and environmental health by protecting our land, air, and water. EPA’s Office of Research and Development (ORD) carries out diverse water-related research activities that focus principally on water quality, including microbial pathogens and chemical contaminants and their impact on drinking water and ecosystems; human and ecological health and risk assessment; water quality criteria to support designated uses of fresh waters; tools for assessment, protection, and restoration of impaired aquatic systems; and improved water and wastewater treatment technologies. Water resource-related research is supported primarily through ORD’s network of national laboratories and its grant programs.

ORD has five branches that support research centers and laboratories at 13 locations across the country: the National Center for Environmental Assessment (NCEA), the National Center for Environmental Research (NCER), the National Exposure Research Laboratory (NERL), the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (NHEERL), and the National Risk Management Research Laboratory (NRMRL). Through NCER, EPA runs competitions for STAR (Science Targeted to Achieve Results) grants and graduate and undergraduate fellowships, provides research contracts under the Small Business Innovative Research Program, and supports other research assistance programs.

NHEERL oversees a network of researchers and facilities, with headquarters in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina; additional laboratories with activities in freshwater resources include the Western Ecology Division (Corvallis, Oregon), the Mid-Continent Ecology Division (Minnesota and Michigan), the Gulf Ecology Division (Gulf Breeze, Florida), and the Atlantic Ecology Division (Narragansett, Rhode Island). Many components of the research conducted by the branches apply to water issues. NRMRL divisions include the Water Supply and Water Resources Division, as well as the Ground Water and Ecosystem Restoration Division. NERL includes the Microbiological and Chemical Exposure Division. EPA primarily emphasizes research relevant to national priorities for safeguarding the environment, although its STAR programs allow investigators to pursue wideranging fundamental scientific issues with direct relevance to applications.

EPA’s share of total federal water resources research (15 percent in FY2000) is strongly dominated by Categories XI (aquatic ecosystems) and V (water quality), followed by II (water cycle) and IV (water quantity management and control), as shown in Figure 4-13. To a significant extent, research in these categories responds to EPA’s regulatory mandates as dictated under the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, the Comprehensive Environmental

FIGURE 4-13 Environmental Protection Agency FY2000 expenditures by major category ($98,970,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Funding for water quality management (V), for example, primarily emphasizes water and wastewater treatment and contaminant fate and transport studies.

U.S. Department of Energy

The mission of the DOE is to advance “the national, economic, and energy security of the United States; to promote scientific and technological innovation in support of that mission; and to ensure the environmental cleanup of the national nuclear weapons complex” (DOE, 2003). The nondefense portion of the department is organized into offices specializing in technologies related to specific energy sources such as fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and renewable energy; each office supports applied research in its field. For example, the Office of Fossil Energy has identified three major goals in its water–energy research and development strategy: reduce the use of freshwater resources in fossil energy production and use, improve the quality and reduce the volume of water used in fossil energy production, and reduce water management costs over conventional technology. Its research accounts for around 10 percent of the DOE total for water resources research.

The majority of the DOE funding (about 90 percent) for water resources research comes from the Office of Science, which sponsors studies of the fundamental physical, chemical, and biological processes affecting the fate and transport of contaminants in the subsurface. Much of this research is sponsored by the Environmental Management Science Program, which supports basic research that could enable new, faster, less expensive, and more effective methods for the cleanup of the nuclear weapons complex.

As shown in Figure 4-14, DOE’s 3.8 percent share of total federal water resources research expenditures is almost exclusively in Category V (water quality management and protection)—not unexpected given its responsibility for some of the most complex hazardous waste sites in the nation. Most DOE-funded water research relates to pollutants and waste treatment associated with the cleanup of hazardous chemical and radioactive waste at former nuclear weapons production facilities. Other water quality research is directed at the pollutant streams from fossil fuel energy production, affecting both surface water and groundwater.

Apart from the water-related research that was reported to the committee, extensive studies are carried out in other programs, but these studies are not classified as “research” for various statutory reasons and were not included in the survey response. For example, since 1978, DOE’s Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management has spent “billions of dollars on characterization studies,” a significant portion of which was focused on hydrology, climate change, and the fate and transport of radionuclides at the proposed nuclear waste repository site at Yucca Mountain, Nevada (DOE, 2002, p. 33). Similarly, the Office of Environ-

FIGURE 4-14 Department of Energy FY2000 expenditures by major category ($26,053,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

mental Management has conducted extensive characterization studies of contaminated DOE sites in support of cleanup efforts.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Several programs within NOAA (which is within the U.S. Department of Commerce) contribute to water resources research. The National Weather Service (NWS) comprises just less than 10 percent of the reported NOAA total, with the rest split fairly evenly between the National Ocean Service (NOS) and programs within the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OOAR). The NOAA water resources research programs have a primarily water cycle and coastal focus, although several other activities concern freshwater resources. (For the purposes of the NOAA survey, “coastal” refers to the land and water area extending from the inland boundary of coastal watersheds to the seaward boundary of the United States Exclusive Economic Zone. In the Great Lakes region, this includes the watersheds of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River.) In particular, the NOAA Office of Global Programs (OGP) carries out most of the fundamental research pertaining to the water cycle, to climate predictability and prediction studies and their role in water resources management, and to the social impacts of climate

variability and change. The NWS through the Office of Hydrologic Development, Hydrology Laboratory, carries out applied research relating to hydrologic and hydraulic modeling and forecasting at all spatial scales. The Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (AHPS) program of the Office of Hydrologic Development provides new hydrologic information and products through the infusion of new science and technology into the operational forecasting process. The inclusion of the Great Lakes within NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) brings NOAA further into areas of freshwater research. NOAA’s coastal research is concerned with agricultural nonpoint source pollution and the resulting hypoxia in coastal waters, as well as other land-based pollutants delivered via runoff. In all the areas, research is conducted both in-house and through grants to external research organizations (universities, nonprofits, and other private sector organizations).

NOAA research accounts for 3.7 percent of the federal total, mainly in Categories II, V, and XI, which focus, respectively, on water cycle processes, water quality management and protection in estuarine and freshwater systems, and aquatic ecosystems (Figure 4-15).

FIGURE 4-15 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration FY2000 expenditures by major category ($24,715,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), within the Department of the Interior, is a major supplier of drinking and irrigation water and hydroelectric power. Its mission is confined to the 17 western states. As an operating agency, USBR water resources research is concentrated on applied topics of water development and management. USBR focuses on four main areas: improving water and hydropower infrastructure reliability and efficiency, improving water delivery reliability and efficiency, improving water operations decision support with advanced technologies and models, and enhancing water supply technologies. Examples of research include desalination, river system modeling, fish passage and entrainment, and operational efficiency enhancements.

USBR research accounts for 2 percent of the federal agency total and is distributed across Categories II (water cycle), III (water supply augmentation and conservation), IV (water quantity management and control), V (water quality management and protection), and VIII (engineering works) (see Figure 4-16). Consistent with its mission as a nonregulatory/operating agency, the USBR devotes a large part of its research expenditures to support the operation of water control structures as well as desalination.

FIGURE 4-16 U.S. Bureau of Reclamation FY2000 expenditures by major category ($14,207,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

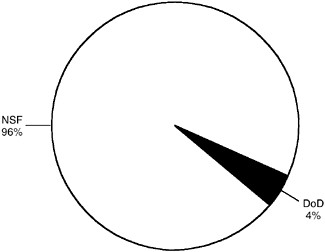

Historically, NASA has developed satellite missions in broad support of many different problems related to the earth sciences including environmental change, tectonophysics, oceanography, hydrology, and glaciology. Science teams are formed early in the process of mission design and are involved with converting satellite measurements to useful science products. Once useful information becomes available on a routine basis, NASA provides funding to university and other researchers for innovative application toward enhanced understanding of critical earth science questions. As a result, it is difficult to determine the direct financial influence of NASA programs on hydrologic sciences. Only the more recent satellite missions (e.g., Aqua, Terra, TRMM) have had continental hydrologic sciences as a theme. With most other missions (e.g., TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason-1, Landsat, GRACE), the products support a myriad of other science programs in oceanography, environmental change, agriculture, and forestry. Nevertheless, data from these missions are beneficial for hydrologic sciences, especially for large-scale studies. The NASA estimate of the annual support for water resources research (1.5 percent of the federal total) is primarily directed to a better understanding of fundamental water cycle processes (Category II), as illustrated in Figure 4-17. This includes direct research support to investigators addressing specific hydrologic problems. There has been minor support for studies

FIGURE 4-17 National Aeronautics and Space Administration FY2000 expenditures by major category ($10,100,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

involving water quality. Because the total NASA expenditures in satellite development and in operation and funding of science teams for the various missions are of a magnitude that would dwarf all other research expenditures considered in this report, and because the percentage of those activities devoted to water resources research is impossible to determine, they are not included in the NASA survey response.

Department of Health and Human Services

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has over 300 research and service programs in 11 operating units, eight of which are in the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS). Two major units of the PHS are the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Both NIH and CDC house water-related research activities, but neither has federally mandated regulatory authority for water-related research or management.

NIH’s environmentally related research is focused in the National Institutes of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The mission of NIEHS centers on reducing morbidity linked to environmental causes. The agency supports research, prevention, intervention, and communication programs. NIEHS includes the National Toxicology Program, which conducts toxicological research; examines reproductive, developmental, cancer, and immunotoxicity outcomes; and develops alternative models. NCI conducts and supports research and its application to prevent, control, detect, diagnose, and treat cancers. The intramural research unit contacted to respond to the survey was the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics’s Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology Branch, which conducts epidemiologic studies to evaluate cancer risks and determines whether they are associated with water contaminants, primarily chemicals. (Thus, the survey does not reflect research conducted or funded by other intramural research programs or extramural grants at the NCI.)

CDC provides health surveillance programs to monitor and prevent disease outbreaks and exposures, conducts research, implements programs and services to prevent disease, and maintains vital statistics and other health databases for the nation. However, CDC neither has funding legislatively directed toward water resources, nor does it have a research program specifically directed toward linking water contaminants and human health outcomes. The agency has recently consolidated with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). ATSDR’s mission is focused on preventing hazardous exposures from waste sites and related adverse health outcomes. The agency accomplishes its mission through the conduct of public health assessments, health studies, surveillance activities, health education services, and toxicological profiles of hazardous chemicals. Two programs account for nearly three-quarters of the agency’s water-related funding—the Research Program on Exposure-Dose Reconstruction (EDRP) and the Great Lakes Human Health Effects Research Program (GLHHERP). The

EDRP conducts applied research to reconstruct past and model potential levels of contaminants in environmental media and water distribution systems from the source to the receptor populations. The GLHHERP is focused on the 11 critical contaminants identified by the International Joint Commission (United States and Canada). The program characterizes exposures to these contaminants; identifies at-risk populations; investigates the potential for acute and chronic adverse health outcomes; and conducts community-based research, education, and interventions.

The total water resources research funding from DHHS in FY2000 was $9.13 million, all in Category V-H (effects of waterborne pollution on human health), and thus, no figure of the DHHS breakdown is provided. During the three years of the survey period, the NIEHS contribution ranged from 48 percent to 68 percent of the DHHS total, the ATSDR contribution ranged from 18 percent to 51 percent, and the NCI contribution ranged from 1 percent to 14 percent.

Budget Breakdown by Major Modified FCCSET Category

A final level of analysis involves considering which agencies supported the 11 major modified FCCSET categories. Of the 11 major categories, multiple agencies play significant roles in six, while the remaining five are largely within the domain of a single agency. While the data were not reported in terms of the continuum from basic to applied research, nor from the standpoint of external grants vs. in-house agency research, some inferences can be drawn from the liaison reports, the stated agency missions, and the experience of committee members.

As shown in Figure 4-18, research into the nature of water (Category I) is funded primarily by NSF, with a small percentage from the USGS. Most of this funding is expected to support basic research in universities and other research organizations.

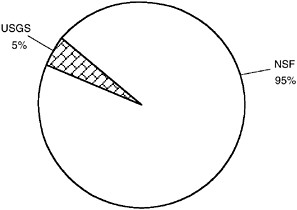

Research into the water cycle (II) is the third-largest funding category and is well distributed across the federal agencies (as shown in Figure 4-19). NSF, USDA, and USGS together provide three-quarters of the research funds in this area, but five other agencies, particularly EPA, NOAA, and NASA, also provide research funding. This area likely includes a diversity of subtopics, ranging from fundamental investigations of evapotranspiration and runoff to applied studies in agricultural landscapes. Assuming that the contributions of NSF, as well as some of the funding from USDA and EPA, are through extramural grants, perhaps one-third to one-half of the research occurs at universities and research institutions, and the remainder is conducted by federal agency scientists.

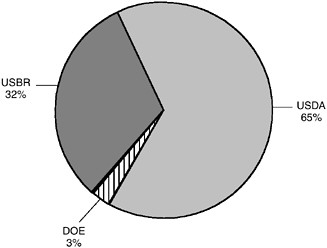

Research into water supply augmentation and conservation (Category III) is largely through the USDA, although USBR contributes about one-third of the total via desalination work (see Figure 4-20).

As shown in Figure 4-21, nearly half of the research into water quantity management and control (IV) is through the USDA, although the EPA and DoD each contribute about 20 percent of the total. This distribution is expected, given

FIGURE 4-18 FY2000 expenditures in Category I (nature of water) by federal agency ($11,153,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

FIGURE 4-19 FY2000 expenditures in Category II (water cycle) by federal agency ($150,835,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

FIGURE 4-20 FY2000 expenditures in Category III (water supply augmentation and conservation) by federal agency ($14,456,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

FIGURE 4-21 FY2000 expenditures in Category IV (water quantity management and control) by federal agency ($45,629,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

the importance of controlling polluted runoff from agricultural lands within USDA and given EPA’s interest in understanding the impact of different land uses on surface water and groundwater flow rates. This research activity is presumed to include a mix of agency science, contracts, and external grants.

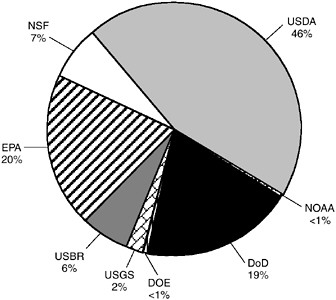

Research into water quality management and protection (Category V) is the largest single funding category and is arguably the most widely distributed across agencies. Six agencies (EPA, NSF, DoD, USGS, USDA, and DOE) each contribute 13 percent to 19 percent of the total, and three others report 1 percent to 5 percent contributions (see Figure 4-22). All of the water resources research reported by the DHHS falls under the subcategory of understanding the effects of waterborne pollution on human health. However, most of the contributions of the other agencies are widely spread among the eight subcategories. Much of this work likely falls in some intermediate region between basic and applied research, although most of it is likely to be motivated by application. The fraction that takes place in universities and research organizations may exceed one-third, assuming that USDA and EPA each make substantial grants in this area, in addition to NSF.

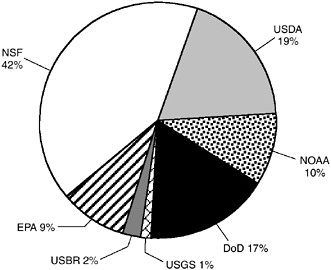

As shown in Figure 4-23, NSF is the largest single supporter of research into water resource planning (Category VI), followed by USDA and DoD. This cat-

FIGURE 4-22 FY2000 expenditures in Category V (water quality management and protection) by federal agency ($191,669,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

FIGURE 4-23 FY2000 expenditures in Category VI (water resources planning and other institutional issues) by federal agency ($9,834,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

egory was interpreted to include academic research into decision-related aspects of human activity and other social sciences within NSF, management and planning in an agricultural context within USDA, and integrated technologies for decision making within the Corps. It is likely that somewhat over half of the research occurs in academic or research institutions, and much is intermediate on the continuum of fundamental vs. applied research.

Over half of the research in water resources data (Category VII) is supported by DoD and USGS, although most of the surveyed agencies play a role (Figure 4-24). Research into data acquisition, storage, standards and delivery, modeling, and information technologies are especially prominent topics for the two agencies leading in this area, which serve such diverse needs as integrated assessment modeling, network design, and interagency collaboration. The majority of this research is presumed to be motivated by near-term application needs and to take place within the federal agencies. It is noted again that this category does not encompass expenditures on actual data collection (see Chapter 5 for a more comprehensive discussion of data collection).

Research into water engineering works (Category VIII) is almost exclusively the province of the Corps (and thus DoD) (see Figure 4-25). This is research of a highly applied and practical nature to support the Corps’ Civil Works program and presumably is carried out by Corps scientists and engineers and through contracts.

FIGURE 4-24 FY2000 expenditures in Category VII (resources data) by federal agency ($8,679,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

FIGURE 4-25 FY2000 expenditures in Category VIII (engineering works) by federal agency ($58,118,000 total). Dollar values reported are constant FY2000 dollars.

As shown in Figure 4-26, research supporting Category IX (manpower, grants, and facilities) is largely through the USGS, followed by NSF. These expenditures by USGS support facilities. Within NSF, these funds support water-related education projects across the directorates and research facilities.

Support for research into Category X (scientific and technical information) is almost entirely from NSF (Figure 4-27).

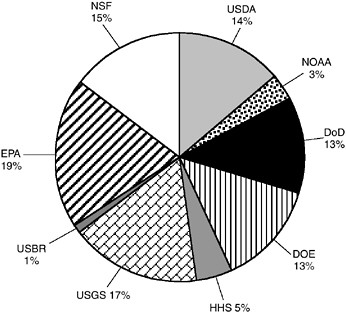

Category XI, aquatic ecosystems, is the second-largest individual funding category and includes significant support from NSF, EPA, USGS, and USDA (Figure 4-28). This category was not present in the original FCCSET categories but was developed to reflect emerging research interests since the 1960s in the areas of ecosystem and habitat conservation, ecosystem assessment, climate change, and biogeochemical cycles. NSF supported research in all four subcategories but allocated less to climate change than the other three subcategories, which it supported roughly equally. EPA funding was entirely for aquatic ecosystem assessment. USGS supported primarily the ecosystem conservation and assessment categories. The USDA funding, primarily from USFS, supports watershed and fish habitat research. If funding support by a number of federal agencies is a measure of importance, only Category V enjoys funding as diverse as that of Category XI (compare Figures 4-22 and 4-28). The funding for aquatic ecosystems protection and management appears to support a healthy balance of agency and external researchers and a range of fundamental to applied research.

Nonbudgetary Survey Information

As mentioned earlier, the survey included questions about the federal agencies’ missions with respect to water resources (see Box 4-1, question 2), as well as questions about the liaisons’ concern irrespective of their agencies’ missions (question 5). Although it is not possible to quantify the liaisons’ responses to these questions, it is useful to examine the similarities between what the agencies’ stated missions are and what the liaisons believe are important emerging water resources issues. The results, presented in Table 4-3, show that few liaisons expressed future issues of concern (column 3) that would not fit into their own agency’s research agenda. Furthermore, it is clear that the current agency missions (column 2) do not add up to a national research agenda for water resources.

In terms of emerging issues (column 3 of Table 4-3), there are several commonalities among the agencies’ responses. The importance of extreme events and the effects of global climate change; the fate, transport, and effects of pollutants; the nature and control of nonpoint source pollution; and the maintenance and restoration of aquatic ecosystems are issues that emerged from more than one liaison response and are also priorities for this committee, as reflected in Table 3-1. Each of these is a complex, multifaceted problem that reflects many scientific, economic, and societal factors; thus, the overlap is not surprising. However, most agency liaisons phrased their perception of these large-scale issues in terms of