How Much is Enough?

Setting Pay for Presidential Appointees

A Report Commissioned

by The Presidential

Appointee Initiative

Gary Burtless

The Brookings Institution

March 22, 2002

Published in March 2002 by

The Presidential Appointee Initiative

A Project of the Brookings Institution

funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts

1730 Rhode Island Avenue, NW

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 496-1330

HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH?

SETTING PAY FOR PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTEES

Introduction

A democratic State is most parsimonious towards its principal agents.

Alexis de Tocqueville,

Democracy in America

Acrucial duty of every new president is to recruit good candidates to serve in senior administration positions. For better or worse, the experience and talents of the president s top appointees will help determine the administration s success in setting and executing policy. The president s ability to recruit talented citizens depends on the attractions of top government jobs, including the salaries and non-wage compensation offered to those who serve in these positions. Strong candidates seldom accept senior administration posts solely, or even mainly, out of pecuniary considerations, but many people will be deterred from public service if a large financial sacrifice is required in order to serve.

This report examines the salaries and non-wage compensation offered to presidential appointees and considers whether they are generous enough to attract the best candidates. The report also compares compensation packages for executive branch officials with those offered to their counterparts in the private sector, and it looks at how today s federal compensation packages compare with those offered in the past.

Congress is ultimately responsible for establishing pay levels for senior appointees in the federal government. This obligation makes Congress vulnerable to the charge of cynical self-interest. The problem stems from the practice of linking salaries of executive branch officials to those of members of Congress. This means that legislators who vote in favor of a pay hike for federal executives are widely seen as voting for an improvement in their own remuneration. Constituent pressure often forces Congress to hold a yes or no vote on scheduled pay raises, even when a law has been carefully crafted to allow salary increases to take place without any explicit action by members of Congress.

Congressional reluctance to vote in favor of pay hikes has meant that the salaries of senior federal executives have followed an erratic course over the past century. Measured either in terms of purchasing power or as a ratio of the average wage of private-sector workers, the annual pay of Cabinet officers and sub-Cabinet officials has fluctuated widely and trended downward over the past few decades. Federal compensation of top officials is determined by the logic of politics rather than dispassionate analysis of supply and demand. Even though the federal pay structure is not calibrated to achieve rational economic objectives, however, the level of top officials pay must have an impact on the recruitment, performance, and morale of senior administration officials.

This report documents the course of high-level federal compensation over the past several decades, describes the process used to set top officials salaries, and shows how and why salary levels have varied over time. A variety of benchmarks can be used to assess the adequacy of federal executive pay. One standard is the purchasing power of salaries. What standard of living can be achieved by an office-holder, assuming her household income while in office consists solely of her federal pay check? Of greater relevance are the wages of other workers, especially those who hold private-sector jobs with similar skill requirements and responsibilities. How does federal executive pay stack up against the salaries paid in similar positions outside the federal government?

Setting Pay in Top Federal Positions

Salaries for presidential appointees are closely linked to the Executive Schedule pay system. Salaries for appointees in 2002 ranged from $166,700 for those in Executive Level I positions (Cabinet-level officials) to $121,600 for those in Executive Level V positions (administrators, commissioners, directors, and members of boards and commissions). (See Table 1.) Members of Congress receive a salary that is linked to Level II of the Executive Schedule, which reached $150,000 in 2002.

The mechanism for setting salaries in Executive Schedule positions has varied over time. In broad outline, the present system can be traced back to the 1960s. In 1967 Congress established a pay-setting procedure to dissociate legislators from the painful task of periodically voting on their own salaries.

Congress created a Commission on Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Salaries, popularly known as the Quadrennial Commission because it was to convene every fourth fiscal year. The Commission was to recommend a pay scale for members of Congress, appointed federal executives, and judges. The Commission s report was to be submitted to the president, who would weigh the panel s recommendations and make a final recommendation to Congress setting out a new pay scale for senior officials. The president s proposal would go into effect unless either the House or the Senate

Table 1. Executive Schedule Salaries, January 2002

|

Level |

Description |

Salary |

|

I. |

Cabinet-level officials |

166,700 $ |

|

II. |

Deputy secretaries of departments and heads of major agencies |

150,000 $ |

|

III. |

Under secretaries of departments and heads of middle-level agencies |

138,200 $ |

|

IV. |

Assistant secretaries and general counsels of departments, heads of minor agencies, and members of some boards and commissions |

130,000 $ |

|

V. |

Administrators, commissioners, directors, and members of boards and commissions |

121,600 $ |

|

Note: Members of Congress receive an annual salary equivalent to ES Level II, or $150,000. Sources: U.S. Office of Personnel Management (2001) http://www.opm.gov/oca/02tables/ex.htm |

||

passed a resolution disapproving the new salary schedule.1

This procedure worked as planned in 1969, when salaries for members of Congress and top federal executives were substantially raised. When the procedure was next applied in the early 1970s, however, the Senate disapproved the proposed salary increase, and top federal pay remained frozen. High rates of inflation in the early 1970s led to a rapid erosion in the purchasing power of top government salaries. In response, Congress enacted the Executive Salary Cost-of-Living Adjustment Act of 1975. The new law provided that senior executives and members of Congress would receive the same percentage annual salary increase as white-collar workers in the civil service unless Congress specifically disapproved of a pay hike.2 If the plan had worked as intended, salary increases in top federal positions would have been smaller but more frequent than under a procedure in which an expert commission and the president recommended a pay hike once every four years. However, Congress has often voted to disapprove the smaller pay hikes envisaged under the 1975 Act, so pay in top positions remained frozen even in years when the white-collar, civil service work force was granted an increase in basic pay. This in turn increased pressure on the Quadrennial Commission to recommend hefty pay increases to allow top fed-eral salaries to catch up with changes in the cost of living and adjustments in the pay scale covering ordinary federal workers.

The 1988 Quadrennial Commission recommended a large increase in pay to offset the drop in purchasing power suffered by top office holders after 1969. President Ronald Reagan accepted the Commission s recommendations and proposed that congressional salaries be increased from $89,500 to $135,000. The size of the congressional pay hike ignited a firestorm of public controversy, prompting Congress to reconsider once again its basic procedure for setting top federal salaries.

The Ethics Reform Act of 1989, which embodied many of the 1988 Quadrennial Commission s recommendations, established the current procedure for making annual adjustments at the top of the federal pay scale. The 1989 legislation provided for a large one-time increase in highranking officials pay. It also defined the process for calculating annual salary adjustments in the Executive Schedule as well as in congressional pay. (Judges salaries are now set under different legislation.) The annual adjustment in top federal salaries is based on the percentage change in private sector wages and salaries as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Cost Index (ECI). The percentage change in high-level federal salaries is calculated as the change in the ECI minus 0.5 percentage points, but the percentage increase cannot exceed the percentage adjustment made in the basic pay of white-collar federal workers (Gressle, 1998). Adjustments at the top of the federal pay scale are supposed to go into effect at the same time as adjustments in white-collar federal pay.

The 1975 Cost-of-Living Adjustment Act and the 1989 Ethics Reform Act were meant to assure regular adjustments in top federal pay that are modest in scale, and rationally linked to rates of salary change in the wider economy and in the federal

work force. That goal has proven elusive. In only 15 out of the 28 years since 1975 were congressional salaries increased. Cabinet-level officers obtained a salary increase in just 16 of the 28 years (see Figure 1). In other years, top-level salaries were left unchanged even though basic salaries for most of the white-collar federal work force were increased. In most cases, the failure to adjust top-level pay also meant that salaries of presidential appointees below Cabinet rank remained frozen, compressing the pay differential between top political appointees in the executive branch and the best paid workers in the civil service.

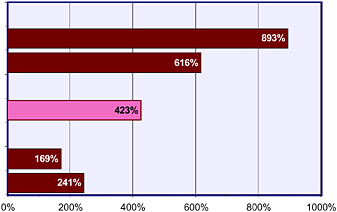

Presidential Appointees’ Pay and the Cost of Living

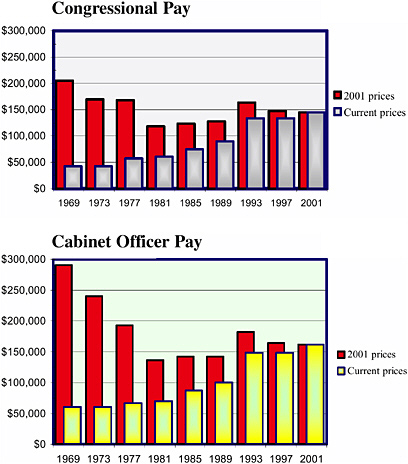

In January 1969 members of Congress were paid an annual salary of $42,500. Cabinet-level officers received a salary of $60,000. By January 2001 salaries had risen to $145,100 for members of Congress and sub-Cabinet officials in Level II of the Executive Schedule. Salaries had climbed to $161,200 for members of the president s Cabinet. While the salary increases may seem large, most indexes of the cost of living rose much faster over the period. Whereas congressional salaries increased 241 percent and Cabinet officer pay rose 169 percent between 1969 and 2001, the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 391 percent.

The implications of consumer price changes for the purchasing power of top federal salaries are displayed in Figure 2. The top panel shows the trend in annual congressional salaries at the beginning of each presidential term from 1969 through 2001. The bottom panel shows the trend in Cabinet officers pay. The light-colored bars show salaries measured in contemporaneous prices, while the dark bars indicate salary levels when prices are converted into constant 2001 dollars. The chart shows that, when salaries are consistently measured using 2001 dollars, congressional pay fell almost 30 percent (from $205,000 to $145,000) after 1969 while Cabinet officer pay shrank 44 percent (from $290,000 to $161,000). Because the level of congressional and Cabinet-officer salaries in turn places limits on the ceiling for salaries received by presidential appointees below Cabinet rank, it follows that most presidential appointees now receive salaries that are worth substantially less than the incomes earned by their counterparts in the early Nixon administration.

Although living costs in general have risen faster than presidential appointees salaries, some costs that are important to new office-holders have risen much faster than others. Housing is always a critical item in family budgets. It is particularly important when families are required to live temporarily a long distance from their permanent homes or to relocate altogether. Presidential appointees must find housing near their new jobs, which frequently requires them to rent or purchase a home or apartment in the Washington vicinity.

Washington-area housing prices are high by U.S. standards, and they have increased even faster than consumer prices in general. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that Washington-area housing costs in 2000 were more than 5 times their level in 1969. In comparison, congressional pay rose by a factor of 3.4 and Cabinet officers salaries by a factor of 2.7 in the same period (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Annual Congressional and Cabinet Officer Pay Measured in Current and Constant Prices, 1969-2001

Note: Price levels are calculated using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U)

Source: see references

Figure 3: Change in Pay and Living Costs, 1969-2000

Most appointees to senior federal positions have reached early middle age, and many have children who are in college or approaching college age. The expense of putting a child through college can be spread across several years, but for most middle-income families the burden of college tuition represents a major challenge to the household budget and one that is difficult to avoid. Like housing costs, the sticker price of a college education has risen much faster than consumer prices more generally. The Department of Education estimates that average tuition, room, and board at a four-year public university increased by a factor of 7.2 between the 1968-1969 and 1999-2000 academic years. Tuition, room, and board at four-year private institutions was almost 10 times higher in 1999-2000 than in 1968-1969. As noted earlier, congressional pay was just 3.4 times higher in 2000 than in 1969, and Cabinet-level salaries were only 2.7 times higher. In light of pay trends since 1969, presidential appointees with college-age children are asked to bear an increasingly heavy burden to finance the college education of their youngsters.

Top federal office holders are not the only Americans who face high living costs, of course. Middle-class families must also struggle to pay higher prices for basic necessities, decent housing, and a college education for their children. One way to compare the situation of presidential appointees with that of middle-class Americans is to compare the annual salaries of a top office-holder with the annual income of a middle-class family. In 2000, the median income of a four-per-

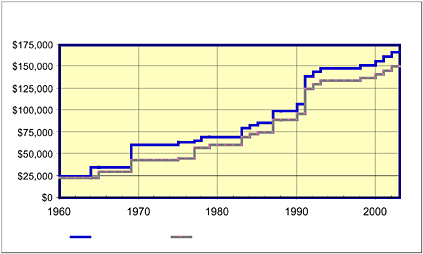

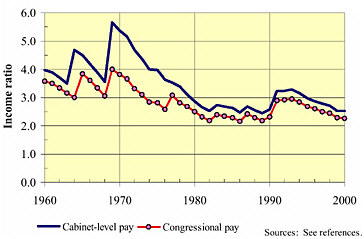

Figure 4. Ratio of Top Office Holders' Pay to Median Income of Four-Person Families

son American family was $62,233. In comparison, a Cabinet officer s annual salary was $157,000—or 2.5 times the median income—and a member of Congress pay was $141,300—or 2.3 times the median income. Both multiples are significantly smaller than was the case in 1969, however, when Cabinet-level pay was 5.6 times the median income and a member of Congress pay was 4.0 times the median income.

Figure 4 shows the relationship between top office-holders salaries and median income over the four decades from 1960 to 2000. It is clear in the figure that the salary increase given to top federal officeholders in 1969 pushed their incomes to a four-decade high compared with the median U.S. income. Even before the 1969 pay hike took effect, however, top federal officials received a salary that represented a large multiple of the income earned by middle-income families. From 1960 through 1968 a Cabinet officer s pay was 4.0 times the median family s income. Between 1996 and 2000 a Cabinet member s pay had fallen to just 2.7 times the median family income. Thus, top officeholders pay has not only failed to keep pace with changes in the cost of living, it has also climbed more slowly than the incomes of the middle class.

Top Federal Salaries in Comparison with Wages Outside the Federal Government

The financial attractiveness of top government jobs depends not only on the purchasing power of federal salaries, but also on the wages available to office-holders if

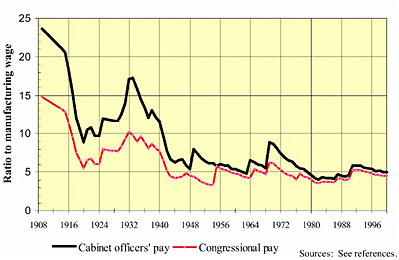

Figure 5. Salaries of Cabinet Officers and Members of Congress Compared with Average Manufacturing Worker's Pay (1909-2000)

they worked in other jobs. When most voters evaluate congressional compensation and Cabinet officers pay, they proba-bly consider salaries in jobs with which they are familiar, including their own. One benchmark for thinking about top federal salaries, therefore, is the pay of a typical person employed outside the federal government.

At the time William Howard Taft became president in 1909, an average production worker in manufacturing earned slightly more than $500 a year. In that same year, President Taft received an annual salary of $75,000, members of his Cabinet earned $12,000, and members of Congress earned $7,500. Federal Cabinet secretaries thus earned an annual salary equal to 24 times the average earnings of a manufacturing worker, while members of Congress were paid a salary equal to 15 times the average manufacturing wage. Between 1909 and 2000, the average manufacturing wage increased at a compound annual rate of 4.6 percent, reflecting the effects of both productivity improvement and economywide price inflation. During those same decades, a Cabinet officer s pay increased 2.9 percent a year, and congressional salaries grew 3.3 percent a year, significantly slower than average wage gains in manufacturing. By 2000, Cabinet mem-bers pay and congressional salaries were approximately 5 times the average earnings of a production worker in manufacturing (Figure 5). If earnings trends among manufacturing workers were typical of wage gains among workers in the wider economy, the long term trend in top

federal salaries has brought federal office holders much closer to the position of an average U.S. worker.

Whether the gap between top government salaries and average pay remains big enough to attract the best candidates to high-level federal positions depends on the motivations of people who are asked to serve, and on the salaries offered by establishments that would otherwise employ them. It is safe to say that few people asked to serve in senior administration posts are recruited from the rankand-file work force of manufacturing plants. Almost all top government officials have a college diploma; many have earned a post-graduate degree.3 Nearly all are drawn from leadership roles in their former places of employment.

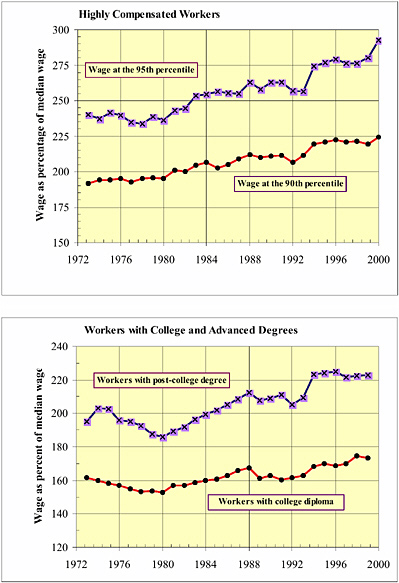

For a variety of reasons, the wages earned by such workers have increased significantly faster than wages paid to rank-and-file workers, especially in the years after 1980. Figure 6 shows trends in the relative earnings of highly compensated and well-educated workers since 1973. The top panel shows earnings trends among workers whose hourly wages place them near the top of the earnings distribution. The lower line in this panel shows the ratio of earnings at the 90th percentile of the U.S. wage distribution to the median hourly wage in the economy. The upper line in the same panel shows earnings at the 95th percentile divided by the median wage. (The wage of a worker receiving the 95th percentile wage was $35.85 an hour in 2000; the median wage was $12.25 an hour.) The hourly wage of highly compensated workers has increased significantly since the 1970s compared with the wages earned by workers in the middle of the wage distribution. In 1980, the 95th percentile wage was 2.4 times the median U.S. wage. By 2000 it was almost 3 times the median wage.

The trend in wages across different educational groups reveals a similar pattern. People with advanced schooling have obtained faster wage gains than workers with average or below-average schooling. The lower panel in Figure 6 shows the ratio of wages earned by college graduates and workers with a post-college degree compared to the median U.S. wage. The earnings premium provided to workers with above-average education has risen markedly since 1980. People who have average or below-average schooling may regard this trend as unfair because it hurts their bargaining position, both when seeking jobs and when negotiating for pay increases. The flip side of this is that people with high levels of schooling and exceptional talents have seen their bargaining position improve. They command higher wages relative to the median wage than was the case in the 1960s and 1970s.

The implication of these trends for recruiting senior administration officials is

|

3 |

From The Presidential Appointee Initiative demographic data base: Of the appointments made by George W. Bush to Senate-confirmed positions in the executive branch in 2001, 87 percent had a graduate degree. http://www.appointee.brookings.org/news/handout2.pdf [February 15, 2002] |

straightforward. The wages of people who are most likely to take high-level government positions have increased much faster than those of typical workers. Thus, the relative decline in compensation for top-level federal appointees has been greater than is implied by Figure 5, because the market wage available to senior political appointees has increased noticeably faster than the average manufacturing wage.

Consider earnings trends among men who have obtained a post-college degree, who work in a full-time, year-round job, and who are between 45 and 54 years old. From 1977 through 2000, the average annual earnings of this highly educated group increased 5.2 percent a year. This was faster than the wage gain of production workers in manufacturing, who saw their earnings climb 4.5 percent a year during the same period. It was considerably faster than salary gains for Cabinet-level positions, which averaged just 3.8 percent a year between 1977 and 2000. Although these differences in the rate of wage gain may seem small, over a twodecade period they make a big difference in relative earnings. For example, if the wages of two workers are initially the same but one worker receives pay increases that are 1.4 percent faster than the other, at the end of 20 years the worker with faster wage gains will earn one-third more income than the worker who receives smaller raises.

To determine how top federal salaries compare with salaries in high-level positions outside of government, it is useful to identify the main sources of presidential appointees. Table 2 shows the employment experience of presidential appointees who served in the federal government between 1984 and 1999. The tabulations are based on a survey of 435 former officials who served in an Executive Schedule position requiring Senate confirmation (Light and Thomas, 2000). The most

Table 2. Employment Experience of Senate-Confirmed Presidential Appointees

|

Type of organization |

Employment immediately before appointment |

Employment immediately after appointment |

|

Federal government |

35 % |

13 % |

|

Business or corporation |

18 |

34 |

|

Law firm |

17 |

21 |

|

Eduational institution or research organization |

14 |

16 |

|

State or local government |

8 |

2 |

|

Charitable or nonprofit organization |

4 |

7 |

|

Interest group |

1 |

2 |

|

Other or no answer |

3 |

5 |

|

Source: Light and Thomas, The Merit and Reputation of an Administration (Washington: The Presidential Appointee Initiative, 2000), pp. 35-36. |

||

important single source of presidential appointees is the government itself. About one-third of appointees worked previously in the federal government, and one in 12 came from state or local government. Among the presidential appointees who came from outside the government, the most important sources of top officials were businesses, law firms, and educational and research institutions. These three sources account for nearly half of all appointees.

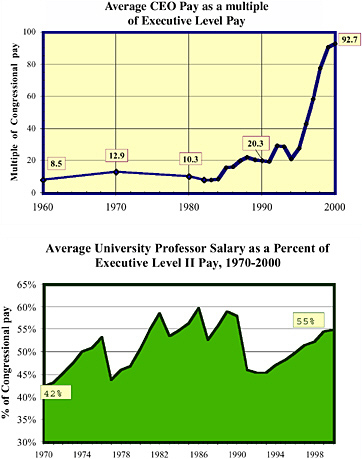

Information on top-level business compensation is available for publicly traded companies and is tabulated by Business Week in an annual survey of CEO pay. As most newspaper readers know, compensation of top business executives has soared since the early 1980s. Measured as a multiple of the annual pay of a member of Congress, average CEO compensation jumped from less than 13 before 1980 to 93 in 2000. While compensation for corporate executives below the rank of CEO did not increase as fast, it also rose much more rapidly than salaries of Cabinet and sub-Cabinet officials.

University pay is tracked by the Department of Education and the American Association of University Professors (U.S. Department of Education, 2001, and AAUP, 2001). Their tabulations allow us to measure trends in the salaries of college and university faculty who have the rank of full professor at accredited institutions. The lower panel in Figure 7 shows the average salary of college professors measured as a percentage of the annual pay of members of Congress. The chart indicates that while the relative pay of senior federal executives and professors has cycled up and down over time, the long-term trend has favored professors. Their average salary in the early 1970s was just 42 percent of a Congressman s salary. By 2000 their average salary represented 55 percent of congressional pay.

The annual salary survey conducted by the AAUP also shows that recent trends in relative college pay have strongly favored professors who teach in well paid disciplines and in highly regarded institutions. The AAUP divides teaching disciplines into four categories depending on average salary level. In 1979-1980, the pay gap between professors in the highest- and lowest-paid disciplines amounted to 19 percent of average pay in the low-pay disciplines. By 1999-2000, the gap had widened to 34 percent of average pay. A similar trend has led to bigger gaps between salaries at selective research universities and at less selective two- and four-year colleges. Wider gaps have also opened up within the same institutions between salaries of top professors and professors earning the median salary, and this trend is especially noticeable in the major research universities (AAUP, 2001, Tables 3, 4, and 6). The strongest professorial candidates for presidentially appointed positions are usually recruited from among the best teachers in the nation s strongest research universities. The salaries paid to the top professors have climbed much faster than salaries

paid to average professors, which suggests that pay increases for top administration jobs have failed to keep pace with salaries earned by the nation s top educators.

It is useful to compare salaries in specific administration jobs with the salaries earned in comparable positions outside of the federal government. This kind of comparison highlights the financial sacrifices that highly qualified candidates must make in order to accept a senior position in an administration.

Figure 7. Top Federal Salaries Compared with Business Executive and University Professor Pay

Sources: see references

Table 3 shows job titles and salaries of seven presidentially appointed positions as well as typical salaries of positions from which appointees might be drawn. The first position on the list is assistant secretary for tax policy in the Department of Treasury. The person who holds this job is responsible for developing and analyzing the administration s tax proposals. Candidates are drawn from both legal and academic backgrounds. The job is an Executive Schedule Level IV position, which in 2000 paid its incumbent an annual salary of $122,400. In comparison, equity partners in New York s 25 largest law firms could expect to earn more than $1.2 million as their share of partnership net income, roughly 10 times the salary received by an assistant secretary of the Treasury. Indeed, major law firms offered starting salaries to new law school graduates, not including bonuses, that exceeded the assistant secretary s pay. The Executive Level IV salary is more competitive in recruiting academic economists and lawyers, whose annual salaries are often close to those of senior administration officials. The academic salary shown in Table 3 probably understates the income that candidates would have to give up to accept the position of assistant secretary for tax policy, however. Many academics who are knowledgeable about tax policy have consulting incomes in addition to their university salaries. People who accept a senior administration post must give up their outside labor income while they hold office.

Table 3. Comparison of Salaries in Presidentially Appointed Positions and in Positions Outside the Federal Government, 2000

|

Federal position/Comparison position |

Compensation |

Federal salary as % of outside salary |

Year |

||

|

1. |

Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy, Department of Treasury |

$ 122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

Equity partner, 25 largest NY firms |

1,216,039 |

10% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

First-year salary of associates (excluding bonus), 25 largest NY firms |

125,000 |

98% |

|

|

|

c |

Full professor, private research university |

107,633 |

114% |

|

|

2. |

Commissioner of the IRS, Department of Treasury |

130,200 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

Equity partner, 25 largest NY Firms |

1,216,039 |

11% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

General counsel, Fortune 1,000 company (salary plus bonus) |

822,236 |

16% |

|

|

|

c |

Partner in accounting firm |

152,581 |

85% |

1999 |

|

3. |

Assistant Secretary, Administration for Children and Families, DHHS |

122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

State welfare officials (CA, FL, IL, NY, TX) |

111,315 |

110% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

Full professor, private research university |

107,633 |

114% |

|

|

4. |

Director of National Institutes of Health, DHHS |

122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

President of selective private research university |

402,131 |

30% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

Base pay of a CEO physician |

302,000 |

41% |

|

|

|

c |

Median salary, president of private university |

185,361 |

66% |

|

|

5. |

Commissioner of FDA, DHHS |

122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

Chief executive officer, pharmaceutical company |

1,987,500 |

6% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

Base pay of a CEO physician |

302,000 |

41% |

|

|

|

c |

Base pay of medical director/clinical department head |

225,535 |

54% |

|

|

6. |

Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education, Dept. of Educ. |

122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

President of selective private research university |

402,131 |

30% |

2000 |

|

|

b |

Median salary, president of public university |

138,671 |

88% |

|

|

|

c |

Full professor, private research university |

107,633 |

114% |

|

|

7. |

Assistant Secretary for Elementary and Secondary Educ., Dept. of Educ. |

122,400 |

|

2000 |

|

|

|

a |

School district superintendents, districts with 200,000 or more students |

207,742 |

59% |

2001 |

|

|

b |

School district superintendents, all |

182,863 |

67% |

2001 |

The commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service is responsible for administering an agency with 98,000 employees and an annual budget of $8.2 billion. The commissioner holds a Level III Executive Schedule position, which in 2000 entitled him to receive a salary of $130,200. This is roughly one-tenth the average net income of a partner in a large New York law firm and one-sixth of the salary and bonus received by the general counsel of a major U.S. corporation. When compared with a partner s income in a U.S. accounting firm, however, the commissioner s pay seems more competitive.

Senior administration jobs offer competitive pay when good candidates for the job can be recruited from public agencies or nonprofit organizations. For example, the assistant secretary of Health and Human Services for children and families receives a salary that is slightly above the average salary of Cabinet secretaries for welfare and social services in the five largest states. Of course, good candidates for this position might also be drawn from nonprofit charitable organizations that deal with social welfare issues. Using salary data supplied by Abbott, Langer & Associates, an employee-compensation consulting firm, the Congressional Budget Office recently compared the compensation paid to top federal officials with that paid to the CEOs of large nonprofit organizations. The nonprofit organizations included in the Abbott, Langer survey were ones involved in charity, education, and the professions, and each organization had a minimum annual budget of at least $50 million. Although the budgets of these organizations represent a tiny fraction of the budget of the Administration for Children and Families, the median salary of their CEOs was almost one-third higher than that of the HHS assistant secretary. CEOs in the top quarter of the nonprofit pay distribution received salaries that were at least 70 percent higher than the assistant secretary s (Musell, 1999, Table 6). Even though the com-pensation offered in top federal jobs is below that available in the nonprofit sector, many executives of nonprofit organizations would probably be eager to serve as HHS assistant secretary because of the enormous influence of this position.

When a top federal job requires detailed knowledge about science or medicine, however, federal salaries must seem far less attractive. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) provides financial support for much of the nation s research on the prevention, detection, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. Though four-fifths of its budget supports research outside the federal government, the NIH also has a large staff that conducts biological and medical research in government laboratories. Five members of its staff have been awarded the Nobel Prize since 1968. It had an annual budget of $20.3 billion in 2001, and a staff of 17,700, including more than 3,000 research scientists. All directors of the NIH have been physicians, but the size and scope of the Institutes are more like those of major universities than of a health institution. Presidents of selective private research universities received an

average salary that was slightly above $400,000 in 2000, more than three times the pay of the NIH director. The median salary of a private university president is also much higher than that of the NIH director. The director s salary is less than half the average compensation paid to physician-CEOs placed by Witt/Kieffer, the leading executive search firm specializing in recruitment of managers for health care, managed care, and educational institutions. A physician placed as a CEO will typically be responsible for managing a hospital or a health care company, institutions that are far smaller than the NIH.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the federal regulatory agency responsible for ensuring that ingredients in the nation s food supply are not harmful and that drugs and devices used in medical practice are safe and effective. FDA s regulatory mandate requires great technical competence and imposes enormous responsibilities on its staff. The commissioner of the FDA oversees 9,200 employees and an annual budget of about $1.4 billion, equivalent to that of a large university. In 2000, the commissioner was paid $122,400. This was 6 percent of the average pay received by chief executive officers in the pharmaceutical companies whose products are regulated by the FDA. The executive search firm Witt/Kieffer helps recruit physicians to serve as company medical directors and heads of departments of clinical medicine in hospitals and universities. The average base pay of physicians placed in these positions in 2000 was $225,000. Witt/Kieffer s salary estimates exclude incentive bonuses, though bonuses are an important part of the compensation received by physicians who serve as executives. Thus, even excluding bonuses, the average pay of medical directors and department heads in hospitals and universities is almost twice that of the FDA commissioner.

The last two federal positions shown in Table 3 are in the Department of Education. The two assistant secretaries are responsible for administering a combined total of $38 billion in annual spending on the nation s schools, colleges, and universities. Their annual salaries would place them in the lower ranks of public and private university presidents and superintendents of municipal school systems.

Non-wage Benefits

Senior federal executives receive essentially the same non-salary benefits provided to the rest of the civilian federal work force. Although the federal benefit package was once considered generous, primarily because of liberal pensions, it is now thought to be only slightly more generous than the package provided by large private employers (Task Force on Pay and Compensation to the National Commission on the Public Service, 1989, p. 207). The health insurance choices provided to federal employees are efficiently managed and highly regarded, but the government subsidy to the system is not exceptional by the standards of plans offered by other public or private employers.

The federal pension system is sound and offers excellent benefits for long-serving employees. In the past, the Civil Service Retirement System provided extremely generous and inflation-protected pensions to workers who spent most of their careers in federal service, but that system is being gradually replaced by a new system. New appointees to senior federal posts are enrolled in the successor pension plan. The new Federal Employee Retirement System (FERS) and Thrift Saving Plan (TSP) are similar, both in structure and in generosity, to good pension programs offered by large private employers. About one-third of presidential appointees work in federal jobs before accepting a presidential appointment. For these workers, their contributions to the FERS during their service in an administration job will add to the value of their federal pension. Even those workers who enter federal service from outside the federal government will derive some benefit from their participation in the FERS and TSP systems, because both retirement saving plans provide benefits that are portable when workers leave federal employment, even if they leave before retirement age.

One element of federal employment that remains generous by private-sector standards is employee job security. However, the job protection available to ordinary civil servants has no value for political appointees. They serve at the pleasure of a president who has a limited term in office. Private-sector executives who accept a senior administration job will usually be disappointed by the non-wage benefits connected to federal service.4 While the TSP offers federal workers an attractive opportunity to save in a tax-preferred account that is subsidized by an employer match, presidential appointees will not find many opportunities to supplement their salaries with incentive payments, bonuses, or stock options. While appointees are eligible for the same recruitment and relocation bonuses as other senior federal executives, there is little evidence that the agencies that have discretionary authority to pay these bonuses often use them. Incentive payments and bonuses are common for executives in private business and are even offered to executives in large public institutions, such as universities and hospitals. To be sure, the non-salary benefits offered by the federal government are rightly seen as excellent by rank-and-file workers. From the perspective of a highly compensated executive in the private sector, however, federal benefits will not seem exceptional. On the contrary, an executive who has participated in a private firm s profit-sharing or stock-option plan is likely to view federal benefits with dismay. Like federal salaries, the non-wage benefits provided in top government positions are much less generous than those provided to senior executives in profit-making corporations and partnerships.

Any survey of the non-wage benefits connected with senior federal service would be incomplete without some description of the hurdles that nominees face in their quest for confirmation. Nominees to a presidentially appointed position must submit at least four different forms before they can be confirmed in their jobs. According to a tabulation by presidential scholar Terry Sullivan, nominees must respond to a total of roughly 233 questions, of which 116 are unique to one form, 99 are similar on at least two of the forms, and 18 are identical on at least two of the forms (Sullivan, 2001). Many of the questions treat detailed aspects of a nominee s (and a nominee s spouse s) income sources and financial holdings. For nominees who have accumulated substantial wealth inside or outside of a pension plan, answering these questions often requires the assistance of a professional accountant or financial advisor. In addition to the financial expense of completing the required forms, nominees may feel they must sacrifice their family s privacy in order to gain confirmation to the job. This is a fringe benefit of senior federal service that many qualified candidates would happily live without.

The Attractions of High-Level Positions

Most people willing to accept a top-level government job recognize that the pay in such a job can rarely match that provided by a comparable position in the for-profit sector. Legislators who are answerable to voters cannot allow top salaries to exceed some undefined limit that most Americans regard as tolerable. If U.S. voters had a say in determining compensation in the private sector, many would probably vote against some of the salaries displayed in Table 3. Voters sense of fairness has only a small impact on the salary structure of private employers, but it is crucial in determining pay at the top of the federal organizational chart.

Voter ignorance may play a role in shaping public attitudes toward compensating high-level government appointees. More than three-quarters of American adults believe the financial rewards of federal employment play a big or moderate role in the decision of high-level appointees to serve in administration jobs (Labiner, 2001, p. 16). Forty-three percent think Cabinet appointees, such as the secretary of State or secretary of Defense, obtain salaries in top administration jobs that are equal to or greater than those they would receive in a senior position outside of government (Labiner, 2001, p. 17). In view of the salary comparisons displayed in Table 3, this view seems preposterous, but it is one held by a large minority of voters. Many adults are apparently unaware of the compensation received by senior executives, doctors, lawyers, and scientists in the private sector, but others may have little knowledge of the actual salaries that are paid to top federal officials.

One puzzle is voters unwillingness to countenance salary schedules that past generations of voters were willing to accept. Based on the evidence in Figures

4 and 5, it is plain that Americans were once willing to tolerate much higher levels of compensation in top federal jobs. The big drop in relative compensation that occurred after the Great Depression can probably be explained by a general compression of American wages during and after World War II (Goldin and Margo, 1992). Top office-holders salaries fell in comparison with ordinary workers wages, but a similar compression in pay also occurred in the private sector.

It is a little harder to explain government pay trends after 1970. U.S. wage inequality increased dramatically after the 1960s, especially in the two decades after 1980 (see Figure 6 and the top panel of Figure 7). Private-sector employers have moved toward a pay system in which workers with the broadest management responsibilities and the most highly prized technical skills command an outsize share of a firm s total compensation. Some observers argue that these key workers are now also exposed to an outsize risk that their incomes will fall, but it is hard to find evidence that highly compensated workers have recently been exposed to any greater income risk than workers who earn average or below-average wages. In any event, political appointees have faced income risk since the birth of the republic. They serve at the pleasure of the president, and their job will almost certainly end when an administration leaves office. Political appointees serve in top administration jobs for an average of less than two years. The responsibilities of top federal jobs have not shrunk, but, unlike salaries for top privatesector jobs, the pay has. It is curious that Americans appear willing to tolerate bigger pay disparities in private markets, while insisting in the voting booth—or at least on talk radio—that top government salaries should be severely curbed.

People who accept top federal appointments derive non-monetary benefits from their service, of course, and these benefits help to explain why government service continues to attract outstanding candidates. Many public-spirited Americans are eager to serve in influential or highprofile positions, even if the financial rewards are far below those obtainable in a private-sector job. Experience in a senior government job allows workers to acquire skills, knowledge, and reputation that may have considerable value outside the government. Few appointees say they are forced to accept a big cut in earnings when they leave federal office. More than one-third of the appointees who served between 1984 and 1999 say they modestly or significantly increased their earning power as a result of holding a senior administration job (Light and Thomas, 2000, p. 35).

On balance, however, the non-monetary advantages of serving in a top federal job are no larger today than they were three decades ago, when top federal salaries were substantially higher (in constant dollars). The economic rewards of federal service have fallen, especially in comparison with wages and benefits offered to highly qualified candidates in the private marketplace. No one can be sure whether these trends in

pay, inside and outside the government, have affected the caliber of people willing to serve in top federal positions.

The crucial question for voters is simple. Do we want the federal government to be deprived of the talents of highly competent people who may be deterred from public service by the financial sacrifice they must accept in order to serve? No careful observer would claim that the best public servants are motivated solely by pecuniary rewards, but no rational observer should expect that the decision to serve in a top-level position is totally divorced from financial considerations. For the past quarter century top executives, doctors, lawyers, and scientists in the business and academic worlds have seen their compensation climb much faster than the wages of ordinary workers. Over the same period, top federal appointees have seen their pay shrink, both in purchasing power and in relation to the pay of average workers. Talented people who are concerned about their families well-being may be deterred from accepting top federal jobs under these circumstances. If financial considerations play any role at all in candidates decisions to serve an administration, the drop in top federal pay has deprived the federal government of an ever-larger fraction of the nation s most talented people.

REFERENCES

American Association of University Professors. 2001. Uncertain Times, The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession 2000-2001.

Goldin, Claudia, and Robert A. Margo. 1992. The Great Compression: The U.S. Wage Structure at Mid-Century, Quarterly Journal of Economics (February).

Gressle, Sharon S. 1998. Salaries of Federal Of ficials: A Fact Sheet. CRS Report 98-53 GOV (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

Labiner, Judith M. 2001. A Vote of No Confidence: How Americans View Presidential Appointees (Washington, DC: The Presidential Appointee Initiative).

Light, Paul C. and Virginia L. Thomas. 2001. Posts of Honor: How America’s Corporate and Civic Leaders View Presidential Appointments (Washington, DC: Brookings and Heritage).

Musell, R. Mark. 1999. Comparing the Pay and Benefits of Federal and Nonfederal Executives. (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office). (http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=1763&sequence=0&from=1 [January 17, 2002]).

Sullivan, Terry. 2001. Repetitiveness, Redundancy, and Reform: Rationalizing the Inquiry of Presidential Appointees, in G. Calvin Mackenzie, ed., Innocent until Nominated: The Breakdown of the Presidential Appointments Process (Washington, DC: Brookings), pp. 196-230.

Task Force on Pay and Compensation to the National Commission on the Public Service. 1989. Facing the Federal Compensation Crisis in National Commission on the Public Service. Leadership for America: Rebuilding the Public Service – Task Force Reports to the National Commission on the Public Service (Washington, DC: National Commission on the Public Service).

U.S. Office of Personnel Management. 2001. Federal Civilian Workforce Statistics: Pay Structure of the Federal Civil Service as of March 31, 2001. (Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Personnel Management).

SOURCES FOR DATA IN FIGURES

Executive Schedule and Congressional pay amounts used in Figures 1-5 and 7.

Hartman, Robert W, and Arnold R. Weber. 1980. The Rewards of Public Service: Compensating Top Federal Officials. (Washington, DC: Brookings).

Office of Personnel Management. 1997. Executive Order 13033 Adjustments of Certain Rates of Pay and Allowances.

__________. 1998. 1998 Executive Schedule. (www.opm.gov/oca/98TABLES/exec_ses/exesepdf/98EX.PDF [December 3, 2001]).

__________. 1998. 1999 Executive Schedule. (www.opm.gov/oca/99TABLES/Execses/html/99excsch.htm [December 3, 2001]).

__________. 2001. 2001 Executive Schedule. (www.opm.gov/oca/01tables/execses/html/01execsc.htm [December 3, 2001]).

Senate Historical Office and Senate Disbursing Office. 1999. Salaries of Members of Congress: Payable Rates and Effective Dates, 1789-2000, Report No. 97-101 1GOV. (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress). www.senate.gov/learning/stat_17.html

US House of Representatives, Committee on Post Office and Civil Service. 1964. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1973. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1980. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1988. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1996. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

US Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs. 1984. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1992. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 2000. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

US Senate Committee on Post Office and Civil Service. 1960. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1968. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

__________. 1976. United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions.

Figure 3: Changes in Living Costs

Washington, D.C., housing costs.

Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer housing cost index for Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area.

Freddie Mac. 2001. Conventional Mortgage Home Price Index, Q2 2001 Release. (www.freddiemac.com/finance/cmhpi/past/2001/q2/msas.xls [December 4, 2001]).

College tuition, room, and board.

US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2001. Digest of Education Statistics 2000, table 313.

Figure 4: Median Income of Four-Person Families

U.S. Census Bureau Web site, http://www.census.gov/hhes/income/histinc/f08.html [January 4, 2002].

Figure 5: Average Earnings of Production Workers in Manufacturing

Bureau of Labor Statistics Web site, http://stats.bls.gov/ces/home.htm#btables [January 4, 2002] (Series ID: EEU30000004).

Figure 7: Relative Earnings of CEOs, University Professors, and Members of Congress

CEO pay.

Business Week, Annual surveys of executive compensation.

Professor pay.

American Association of University Professors. 2001. Uncertain Times, The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession 2000-2001, table 1.

US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2001 Digest of Education Statistics 2000, table 238.

Sources of salary information in Table 3:

Equity partner in large law firm.

American Lawyer, Profits per Equity Partner: Highest 25 at New York Firms. (July 2000). (www.law.com/special/professionals/ny/profitsperpartner.html [December 4, 2001]).

Starting salaries, associates of 25 largest NY law firms.

New York Law Journal, February 27, 2001. Money Changes Everything.

Full professor pay.

American Association of University Professors. 2001. Uncertain Times, The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession 2000-2001, table 1.

Salary of general counsel, Fortune 1,000 company.

Aman, Catherine, September 24, 2001. Before the Fall, Corporate Counsel

Partner pay, accounting firm.

Reichardt, Karl E, and David L. Schroeder. 2000. IMA 1999 Salary Guide. Strategic Finance (June 2000): 29-41, table 9. Institute of Management Accountants.

State welfare officials.

The Council of State Governments. 2000. Book of the States 2000-2001 Edition, table 2.11.

Presidential pay, selective private universities.

The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2001. Pay and Benefits, 2001 Survey. (chronicle.com/stats/990/2001/ [December 4, 2001]).

Base pay of CEO physicians and medical directors/clinical department heads.

Witt/Kiefer, June 2001. Executive Compensation Study, Compensation Report No. 7.

Median salary, presidents of private and public universities.

Jacobson, Jennifer, September 4, 2001. Should Presidents Give Back Their Raises? The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Chief executive officer, pharmaceutical company.

Lavelle, Louis, April 16, 2001. Executive Compensation Scoreboard. Business Week, pp. 82-108.

School district superintendents.

Council of the Great City Schools. 2001. Urban School Superintendents: Characteristics, Tenure and Salary, p. 2.

About the Author

Gary Burtless, a Senior Fellow in the Economic Studies program, has been a scholar with the Brookings Institution since 1981. His areas of expertise include income distribution, labor and labor markets, poverty, social security, aging, unemployment insurance, minimum wage stan-dards, welfare, and education and training.

Prior to joining Brookings, Burtless was an economist in the Department of Labor, from 1979-81, and in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, from 1977-79. He was a visiting Professor of Public Affairs at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 1993.

This paper was prepared for The Presidential Appointee Initiative, a project of the Brookings Institution funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. The author is grateful to Molly Fifer of the Brookings Institution for excellent assistance preparing this paper and to G. Calvin Mackenzie, Paul C. Light, Sandra Stencel, and Carole Plowfield for their helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and should not be attributed to The Presidential Appointee Initiative, the Brookings Institution, or The Pew Charitable Trusts.