1

Linking Hazards and Public Health: Communication and Environmental Health1

Disasters are the destructive forces that overwhelm a given region or community. These disasters can be natural or human-induced and require external assistance and coordination of services in order to address the myriad of effects and needs, including housing needs, transportation disruption, and health care needs. Disasters pose a variety of health risks, including physical injury, premature death, increased risk of communicable diseases, and psychological effects such as anxiety, neuroses, and depression. Destruction of local health infrastructure—hospitals, doctor’s offices, clinics—is also likely to impact the delivery of health care services. A second wave of health care needs may occur due to food and water shortages and shifts of large populations to other areas.

In order to better understand the capacity needs for addressing health needs during disasters, the National Research Council’s Disasters Roundtable and the Institute of Medicine’s Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine sponsored a workshop on capacity needs during disasters. The summary has been prepared by the Roundtables’ staff as the rapporteur to convey the essentials of the day’s events. It should not be construed as a statement of the Roundtables—which can illuminate issues but cannot actually resolve them—or as a consensus study of The National Academies.

PUBLIC HEALTH RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH DISASTERS

After terrorists attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, and anthrax was spread via the United States Postal Service only a month later, Americans felt ill prepared to respond to crises and to protect

their health and well-being in the event of future attacks. Since then, preparedness activities have generated substantial interest and funding, and, as a result, federal, state, and local leaders are changing practices to prepare to respond to both natural and terrorist disasters; however, the improvements made are not nearly sufficient, noted some participants.

Usually politically motivated, the immediate goal of terrorism is to instill fear and confusion among the public. Immediately following an attack, the public’s fear is transformed into intense preparation for the next crisis; yet, with increasing periods of safety, the public’s sense of complacency tends to trump the preparedness activities, and, according to Dr. Julie Gerberding, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, complacency is the enemy of public health. The public health and emergency management communities, therefore, have been charged with the task of conducting environmental analyses, educating and motivating the public to prepare themselves to mitigate the impacts of the next disaster, and communicating preparedness measures to the public before, during, and after an event. During the discussion, Gerberding reiterated that the public will need to become accustomed to the ideas that preparedness is not all or none. There can always be the potential for a scenario that is one step beyond the current level of preparedness. She further noted that this requires an ongoing sustained investment over time.

THE ROLE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH IN UNDERSTANDING TERRORISM

Prior to designing disaster prevention and response strategies, it is critical to understand the physical and social environment surrounding terror agents. According to Dr. Lynn Goldman, The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, responders to a biological, chemical, or physical attack must be able to determine the following: where the agent is in the environment, where it will spread, who will be exposed, what quantity of the agent to which the victims may be exposed, what will happen to the exposed, what must be done to reduce exposure, and how to best treat victims. To answer those questions, it is necessary to understand the harmful agent, how it reaches the human body, and the health effects that it has on the body.

As Goldman noted, while conventional bombs have accounted for 46 percent of international terror attacks between 1963 and 1993, and 76 percent of domestic terror attacks between 1982 and 1992, biological and chemical agents are of increasing concern. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has classified biological terror agents into three categories, based upon their potential to cause morbidity and mortality. Category A agents, such as anthrax, botulism, plague, and smallpox, are classified as high-priority agents because of their ability to inflict high mortality and heavily tax public health and medical resources. Category B agents, such as ricin, typhus, and Cryptosporidium parvum,

are moderately easy to disseminate, but would cause lower rates of morbidity and mortality. Lastly, Category C agents, such as Hantaviruses and tick-borne encephalitis viruses, are of the third-highest priority because of their status as emerging pathogens that can be engineered for mass dissemination in the future. In addition to conventional bombs, biological, and chemical agents, Goldman noted that nuclear, economic, and cyber attacks are other potential sources of terror.

|

Assessing the terror environment not only allows for monitoring of the sources and routes of exposure, but it also helps to prevent and treat diseases by identifying susceptible and resistant population. —Lynn Goldman |

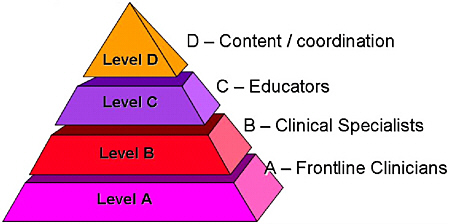

After harmful agents are disseminated, they are transmitted through one of four vectors: water, air, soil, or food (Figure 1.1). Therefore, before agents can exert their dangerous effects, they must be transmitted to humans through inhalation, ingestion, or absorption. The agent, vector, and route of exposure all have a significant impact on the type and severity of the health effects on the exposed population. According to Goldman, assessing the terror environment not only enables monitoring of the sources and routes of exposure, but it also helps to prevent and treat diseases by identifying susceptible and resistant populations. With knowledge of the agent, vector, route of exposure, and expected health effects, exposed populations can be treated at an early stage, subsequently reducing death and disability.

FIGURE 1.1 Possible vectors and routes of exposures by which harmful agents can reach human beings. SOURCE: Ott WR, 1990.

Injury Prevention

In addition to understanding the terror environment, Goldman noted the importance of strengthening both human and physical infrastructure to aid in preventing disasters and reducing their impact, should they occur. To illustrate the benefits of increasing the resistance of structures and people, Goldman discussed how William Haddon’s injury prevention matrix can be applied to a terrorist attack. Haddon studied injuries utilizing concepts from engineering, biomechanics, physiology, medicine, and epidemiology. Through his research, he concluded that, like infectious diseases, injuries are the result of an intricate interaction between agents, hosts, and the physical and social environment (Staniland, 2001). While preventing all terror attacks in the first instance would be ideal, it is important that emergency managers and public health professionals plan for success in controlling and limiting the severity of injuries sustained in the event of an attack. The Haddon Matrix’s ten strategies, and examples of how each strategy can be used to prevent or mitigate the effects of terrorism, are listed below:

|

Building human infrastructure among experts in various fields will help to ensure that trained, experienced professionals are available to respond to future crises. |

-

Do not create the hazard. Prevent terrorism by identifying those who are planning attacks.

-

Reduce the amount of hazard. If all terrorists cannot be eliminated, reduce their numbers.

-

Prevent release of the agent. Monitor known terrorists and identify likely threats.

-

Modify release of the agent. Develop slower-acting explosives.

-

Separate in time or space. Define a no-vehicle zone near a likely target area.

-

Separate with a physical barrier. Construct barriers to reduce access to targets.

-

Modify surfaces and basic structures. Install shatterproof glass in windows.

-

Increase resistance of the structure or person. Design buildings to withstand bomb forces.

-

First aid and emergency response. Train greater numbers of volunteers in first aid and rescue skills.

-

Acute care and rehabilitation. Develop plans and adequate facilities for definitive care (Baker and Runyan, 2002).

To successfully implement injury prevention and control measures, professionals from many diverse fields must work together to prepare for, prevent, and mitigate disasters. Using the injury control matrix developed by Haddon, planners

would consider factors related to the agent (weapon), host (potential victims) and environment (for example, structure of buildings) and whether any of these can be modified pre-event, post-event or during the event. Goldman’s application of the Haddon Matrix to terrorism would require successful collaboration between the public health, law enforcement, and medical, engineering, and emergency management/response communities. Goldman further noted that the public health workforce is dominated by professionals reaching retirement age. Therefore, in addition to responding to public health disasters, public health professionals should also invest resources in training new leaders to ensure that they will be ready to work on the front lines of public health as the current workforce retires. Building human infrastructure among experts in various fields will help to ensure that trained, experienced professionals are available to respond to future crises.

EMERGENCY RISK COMMUNICATION

Having well integrated systems of preparedness is only one element in reducing the impact of disasters upon affected individuals and communities. Effective communication before, during, and after disasters, to culturally diverse audiences of wide-ranging scientific literacy, is a critical component of any preparedness effort. According to Dr. Julie Gerberding, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it is essential to communicate with affected communities, the public, the scientific community, and other stakeholders, to provide the information they need to make the best possible decisions concerning their wellbeing within nearly impossible time constraints. The sense of urgency surrounding emergency risk communication distinguishes it from all other forms of health communication, noted Gerberding. Traditional health communication is aimed at providing the public with information to promote everyday healthy lifestyles. Emergency risk communication, on the other hand, involves providing information that is, by its nature, incomplete, and likely to change over time. While the emerging risk or hazard may be unforeseen and new to the public health community, the communication must, nonetheless, be science-based. Successful crisis communication can be achieved by skillfully developing messages utilizing tested risk communication theories and techniques, which imply an understanding of human psychology and the needs of people in times of crisis, stated Gerberding. The CDC is starting to pre-test messages before threats occur through the use of focus groups around thematic areas to develop tools for public health.

|

Effective communication before, during, and after disasters, to culturally diverse audiences of wide-ranging scientific literacy, is a critical component of any preparedness effort. —Julie Gerberding |

Further, Goldman echoed the issues raised by Dr. Gerberding and noted that the CDC has organized the schools of public health into a number of centers for public health preparedness that are reaching out to the public, public health officials, and first responders. The purpose is to provide information in advance so that people have the core knowledge and skills to make the process smoother. During the general discussions, some participants reiterated the need for further exploring into research communication. These participants, however, cautioned against reinventing the wheel as it relates to communication. They encouraged research that builds on the 20–30 years of social science studies on risk communication as a necessary part of any research program.

The Emergency Risk Communication Audience

Many individuals operate under the assumption that, even if a disaster does occur, it will not affect them; therefore, when it does happen, few people actually have a plan in place to help them react to the disaster, acknowledged Gerberding. While the disaster, alone, can invoke fear, a lack of adequate resources and complete knowledge of the event can further heighten anxiety and threaten an individual’s ability to respond appropriately. During crises, the public looks to politicians, public safety officials, and medical and public health professionals to provide assurance that all possible actions are being taken to alleviate the effects of the disaster, and to recommend actions for individuals to take to ensure their safety.

An individual’s emotional response to a crisis is similar to that of any other life-threatening or grave event. Effective emergency risk communications messages reflect an understanding of the different ways that people react in an emergency, and will attempt to manage those stresses in the population. According to Gerberding, the psychological stages of response to crises are:

-

Vicarious rehearsal—as a result of continuous news coverage, those located in areas removed from the disaster are still able to participate, vicariously, in a crisis that may not pose any real danger to them. When communicators provide recommended actions to threatened communities, those removed from the danger may also take action, heavily taxing the response effort.

-

Denial—denying that the crisis occurred may cause people to delay taking the recommended actions.

-

Agitation and confusion—extreme fear and high anxieties may cause people to become agitated or confused by the warnings.

-

Doubting the credibility of the threat—emergency risk communication messages may be ignored by those who do not believe that the threat is real, or that it may affect them.

-

Stigmatization—following a terror attack, victims believed to be hazard-

-

ous to associate with (i.e., those contaminated with a biological or chemical agent) may be feared, threatening the social unity within a community.

-

Fear and avoidance—this is, perhaps, the most incapacitating of the psychological responses to crises, as fear of perceived or real threats may cause individuals to act irrationally.2

-

Withdrawal, hopelessness, and helplessness—individuals who do not avoid the threat may, instead, feel powerless to protect themselves from it. This poses a challenge for risk communicators because, as individuals withdraw themselves from situations, their messages may not be heard, or their recommendations may not be acted upon (CDC, 2004a).

When planning crisis and emergency communication messages, in addition to understanding the range of emotions affected individuals may experience, it is important to understand that audiences judge the effectiveness of messages by their timeliness, content, and credibility. According to Gerberding, first messages are lasting messages, as the information provided in the message sets the stage for future communications. The speed of the communication indicates that there is a system in place to respond to the emergency, which can help to ease the public’s fear of uncertainty following disasters. In addition, the public is expecting to hear consistent factual information. Inconsistent messages increase anxiety, decrease the likeliness that the public will abide by the communicator’s recommendations, and diminish the communicator’s credibility for future purposes.

The value of effective risk communication cannot be disputed. During crises, skilled risk communication techniques can provide necessary guidance to audiences of differing ages, educational status, languages, and cultural norms. According to Gerberding, in addition to reaching diverse audiences, messages should be prioritized based on the recipients’ distance from and relationship to the threat, as different audiences have distinct concerns. Those closest to the threat should be instructed on how best to protect themselves, while those farther away should be cautioned to remain calm, yet vigilant. The messages will be well received if they are timely, credible, and delivered by a spokesperson that is trusted and familiar with the basic principles of crisis and emergency risk communication.

Emergency Risk Communication Spokesperson

Choosing the appropriate spokesperson to deliver news and recommendations to the public during times of heightened fear and anxiety can be a determin-

ing factor in the public’s response. As Gerberding noted, the spokesperson has four important roles: (1) to remove the psychological barriers within the audience, (2) to penetrate the public’s anxiety and gain support for the public health response, (3) to build trust and credibility for the organizations involved in the response effort, and (4) ultimately to reduce the incidence of illness, injury, and death. Through public appearances, the spokesperson gives human form to the organizations charged with the task of resolving the crisis.

|

Following the 2001 anthrax attacks, 77 percent of people polled had either a great deal of, or quite a lot of trust in their own doctor to give them advice on how to best protect themselves. |

According to a joint study conducted by the Harvard Program on Public Opinion and Health and Social Policy and International Communications Research of Media, PA, immediately following the 2001 anthrax attacks, 77 percent of those polled had a great deal of trust in their own doctor to give them advice on how to best protect themselves. That was followed by high levels of trust in a fire department official, police department official, local hospital official, health department leader, governor, and, finally, a religious leader. On a national scale, 48 percent of those polled had a great deal of trust in the CDC director, followed by: the Surgeon General, the American Medical Association president, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, and lastly, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (Pollard, 2003).

While the foregoing study clearly indicates that clinicians play an integral role in emergency risk communication, according to Gerberding, regardless of the communicator’s professional background, there are five key rules that all spokespersons must follow to increase the likelihood of a successful communication. First, to provide a greater chance that the message will be acted upon, the communicator must exhibit sincere empathy for those affected by the disaster. Risk communication experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 50 percent of a spokesperson’s effectiveness directly relates to their capacity to communicate that they genuinely care about what is happening (Figure 1.2).

Second, Gerberding noted that with continuous news coverage, it is impossible for the spokesperson’s message to always be the first. As explained above, first messages indicate that the responding agencies are prepared and competent to deal with the crisis. To aid in accelerating the network of communication, it is critical to have a command center and emergency communications system, where members from all responding agencies can communicate so that the appropriate information is disseminated to the public.

Third, the content of the risk communication message must be accurate and consistent with other messages. Being wrong not only decreases the public’s

FIGURE 1.2 The spokesperson’s ability to embody empathy and caring is the single most important factor in gaining the audience’s trust. SOURCE: adapted from Covello VT, 2001. Reprinted with permission.

confidence in the response effort, it also destroys the credibility of the spokesperson’s organization for future communications.

The fourth rule is that the spokesperson must be honest. According to Lynn Goldman, of The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, research has shown that, if the public is given honest information, inappropriate behavior will be less likely and many people may even be comforted by the message. In addition, Gerberding noted the value of refraining from delivering completely negative messages. As a result of the emotional component of disasters, if the spokesperson needs to deliver one negative message, it should be balanced with at least three positive messages. Negative words are very difficult to overcome in the context of a crisis; therefore, honest messages should be delivered using positive or neutral words. At the same time, Gerberding emphasized the value of not over-reassuring the public because, if the crisis situation intensifies, the spokesperson and the organization will lose their credibility. Instead, the communicator should acknowledge the uncertainty surrounding the disaster, express that a process is in place to learn more about it, acknowledge the public’s fear and misery, and ask that the public work with responders to find a solution (CDC, 2004a).

|

As a result of the emotional component of disasters, if the spokesperson delivers one negative message, it must be balanced with at least three positive messages. —Julie Gerberding |

Finally, according to Gerberding, the fifth risk communication rule is to get help. If information is unknown, the spokesperson should tell the public that, but, at the same time, emphasize that everything possible is being done to find the answer. Those five rules are useful in creating and communicating an effective risk message; however, the actions suggested in the message will not be acted upon unless the message is disseminated to the public using appropriate methods of delivery.

Working with the Media to Communicate Risk

The media is the fastest, and, in some cases, the only means to circulate important public health information to the public during a crisis; therefore, working with the media is critical to successful communication. While the media is expedient as an emergency broadcast system, members of the media may not have the background knowledge to immediately understand the scientific or technical issues surrounding many disasters. Thus, it is important for spokespersons to speak plainly in order to avoid miscommunication and misinformation. Furthermore, prior to issuing a press release or a statement to the media, Gerberding suggests anticipating and preparing responses to potential questions to ensure that appropriate answers are provided to help achieve a positive health impact.

To disseminate information to the public in the event of a loss in electrical power, Lynn Goldman emphasized the importance of crank radios, battery-powered radios, and landline telephones. Unfortunately, many American homes and businesses do not have such essential preparedness equipment, which can result in a complete breakdown in communication during disasters. It is, therefore, the role of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies and NGOs to communicate the value of preparedness before the next disaster occurs.

Emergency Risk Communication at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

According to Gerberding, emergency risk communication at the CDC is a science application that has rapidly developed since the 2001 anthrax attacks and has been strengthened during the recent SARS, West Nile, monkey pox, avian flu, and influenza outbreaks. Through its Futures Initiative, the CDC has a new capacity to help individuals, stakeholders, and communities obtain the information they need to make the best possible decisions about their well-being. To achieve its goal, the CDC has established a global communications command center with the ability to videoconference with the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Defense, the State Department, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health

Organization. This helps to ensure that the CDC always has the latest information available to distribute to the public.

The CDC has an emergency communications team made up of expert communicators who translate scientists’ findings and recommendations to the media, laboratories, clinicians, state and local departments of health, academia, national and international corporations, and other stakeholders in public health crises (Figure 1.3). The team is currently using focus groups to pretest messages before the threat occurs, so they will have the necessary tools available to broadcast information to the public at a moment’s notice.

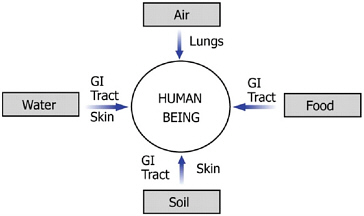

Recognizing clinicians’ vital role in emergency risk communication, the CDC has employed a tiered approach utilizing health educators, clinical specialists, and frontline clinicians to develop two different types of clinician communication (Figure 1.4). First, the “Just in Case” communication trains clinicians in anticipation that a public health crisis might occur. Second, the “Just in Time” communication gives clinicians the latest information to help diagnose, treat, and communicate with patients during a crisis. According to Gerberding, “It is clear to us as an agency that the ability for scientists to translate their science to the media, to the public, and to other communities is central to our success.”

To aid organizations in developing and disseminating emergency risk communication messages to the public, the CDC has created a detailed website, which can be accessed at: http://www.cdc.gov/communication/emergency/erc_overview.htm.

FIGURE 1.3 The CDC’s emergency communications team translates scientists’ findings and recommendations to the media, laboratories, clinicians, state and local departments of health, academia, national and international corporations, and other stakeholders in public health crises. SOURCE: CDC, 2002. Reprinted with permission.