4

Practical Considerations of Emergency Preparedness1

PRACTICAL LOOK AT EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND CRISIS MANAGEMENT: PROTECTING WORKERS AND CONTINUING ESSENTIAL SERVICES

Disasters can be a result of a natural agent, a terrorist act, or an industrial accident. Disasters can have impacts on businesses from both a personnel and an economic standpoint. Because many individuals are at work when disasters strike, it is even more imperative that businesses are a part of the planning for how to manage the impact of disasters and how to prevent them, said Jack Azar of Xerox, Inc. The interest in managing and preventing crises at Xerox started in December 1984 when a disastrous chemical release occurred in Bhopal, India, and 2,000 people were killed as a result of it.

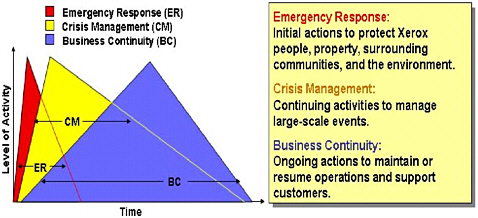

Emergency preparedness at Xerox—which became especially acute due to the events of September 11, 2001—integrates several phases of response from a business perspective: emergency response, crisis management, and business continuity (Figure 4.1). The first phase, which is usually of a short duration, is the emergency itself. This may include a fire or an explosion at a plant or a facility. The initial management of the response to the emergency at a Xerox factory would involve the environmental health and safety committee, as well as the security department of the company. Their actions would be to protect the employees, property, surrounding communities, and the environment. The second phase, crisis management, is when the local event continues or increases in size as a result of uncertainty or crisis fall-out. Sometimes the emergency may last for weeks and cause concern in the public health sector. Thus, this phase needs

to be handled by the senior management throughout the company. The CEO then would decide, based on recommendations from his team, how the company should proceed. The third phase is business continuity. If an accidental explosion occurs at a plant, for example, all operations at the plant are shut down. Sometimes it may be a critical operation to a company, and in some cases it may be the only particular site that has a product or material coming out of the plant to worldwide customers. It is important to know how, in case of a disaster, a business puts its employees back to work, resumes its operations, and keeps the customers happy and the economy thriving, said Azar. At Xerox continuity planning is in the hands of the operations group.

|

It is important to know how, in case of a disaster, a business puts its employees back to work, how it resumes its operations and keeps the customers happy and the economy thriving. —Jack Azar |

The processes of emergency management need to be formalized and standardized throughout the company. Xerox has their facilities and 60,000 employees worldwide, and even though the managerial level employees speak and understand English, it may be challenging to convey the standards to the entire workforce and to ensure that they are carried out. The approach Xerox used to address the challenges was to get together all of the major players from the worldwide facilities and to review the standards in a simple fashion so that the requirements are understood.

Putting the policy in practice, however, is not always easy, noted Azar. In 1999, Xerox started considering what it would do if they lost a site that produced a critical product and it was a sole site of production of that particular material.

FIGURE 4.1 Establishing emergency management in industry. SOURCE: Xerox Corporation. Reprinted with permission.

The driving force was business continuity planning, and it was initiated across the company for consistent operation to ensure that the planning was done in India and Brazil the same way it was done in the United States. At the same time, the environmental health and safety department at Xerox updated their standard for local emergency preparedness.

Modifying Disaster Planning as a Result of the 2001 Terrorist Acts

On September 11, 2001, Xerox had approximately 100 employees in the World Trade Center who were customer service representatives; the company also had business operations located in both WTC buildings. Xerox lost 2 employees and about 100 survived, but it took several days before the company had an accounting of its employees, noted Azar. The experience taught the company a valuable lesson, and it was still in the process of solving the issue of getting its customers back in operation when the anthrax threat began. The threat affected Xerox because the company has 400 operations across the country, primarily in large cities, that do mail sorting for many companies. Some of the facilities were in New York, New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and Florida, where the hot spots for the anthrax operation occurred. Due to the media reports and the constant handling of mail, the employees at Xerox were concerned about their health. In an effort to protect them, the company requested guidance from upper management and assembled a mail safety team. This team followed and tracked the information released by the CDC and the U.S. Postal Services. After the CDC advisory, Xerox made it mandatory to equip its employees with disposable respirators and gloves. The respirators selected to protect from anthrax spores are N95 type. However, it was very difficult to obtain them because they were in high demand. The Postal Services alone bought about 4 million respirators in the course of two weeks, and it took the procurement and environmental health and safety departments at Xerox about two weeks to locate available supplies for 1,000 people.

Shelter in Place

The other challenge that Xerox had was to include shelter in place planning while creating an emergency management plan. Xerox has about 7,500 employees at its Webster facility in New York State. They work within 7 miles of a nuclear power plant. Since Xerox is the largest commercial employer within the 10 mile radius from the plant, it was asked to develop a shelter in place plan in case of terrorism or an accidental release from the facility. At the same time, a crisis management team at the senior levels in the company was created. That team reports directly to the chief of staff, who is in constant communication with the CEO. The team includes operations, health and safety, and security employees as well as public relations, employee communications, and human resources

employees. It took Xerox a year to develop the proper employee communication for a shelter in place plan because previous evacuation alarm systems, used in cases of emergency, forced people to go outside. Thus, Xerox had a challenge to work out a new mode of communicating with its employees. Today, Xerox has two drills a year; one is a fire drill for evacuation where the tone of alarm is very loud, the other is a shelter in place drill where there is a different tone of alarm followed by a PA system communication. Shelter in place procedures were used at the Webster facility in December 2003 when the company had an on-site shooting related to an armed robbery at the Federal Credit Union.

Need for Additional Coordination

Coordination and flow of information is a critical need for industry. There is little coordination within industries, with the majority of the information sharing occurring through interactions with various governmental agencies. Companies do communicate in order to benchmark operations for renewing business, but the effort is not systematic and does not focus on emergency management. Similarly, additional communication needs to occur between industry and government agencies, noted Azar. Health and safety teams have difficulty obtaining accurate information. Sometimes information on government web sites is contradictory, and it is difficult to talk to someone to obtain accurate information. In the case of anthrax, unless one knew someone at the CDC, it was difficult to obtain good advice. Azar concluded by referring to the need for a more open process as there are more than 100 million people who work in the sector and very often an emergency happens during work hours.

NGO’S ROLE IN PUBLIC CAPACITY BUILDING: THE AMERICAN RED CROSS

The American Red Cross is an organization that is directly engaged in the neighborhoods where people live. Unlike many federal agencies, the American Red Cross is not a science agency; it does not have medical experts, seismologists, meteorologists, or hydrologists to conduct research, said Rocky Lopes of the American Red Cross. However, it does have many people who provide a great variety of accurate, appropriate, and sensitive information to the public. The American Red Cross collaborates extensively with a number of agencies in order to provide accurate and understandable information, said Lopes.

The American Red Cross works very closely at the national level to inform the public of appropriate actions. Lopes noted that some of the existing emergency preparedness information that can be found throughout the country is not based on science; it is folklore that interferes with people’s understanding about what to do. For example, some people think that in case of a hurricane one should cover only the windows in the front of one’s home, but hurricane winds

come from all directions, not just the front of a building. Thus, the American Red Cross works closely with FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security, and the National Weather Service to convey the same message so that wherever people turn in their process of verification, they get consistent advice.

Emergency planners need to enable people to understand both what can happen and what actions they can take, and to understand that people are looking for information from a variety of sources. While federal government agencies have substantial information on emergency preparedness, emergency planners need to take into consideration that there are many people in the United States who do not turn to government for information, or trust government, asserted Lopes.

Generally, people trust organizations that provide credible, reliable, believable, and meaningful information to them, asserted Lopes. This means that some NGOs are well-positioned with certain segments of the public and therefore have a greater reach and level of penetration within that segment. But some agencies and organizations need to get over the perception of the ownership of message, noted Lopes. When it comes to emergency preparedness, it should not be the Red Cross message, a government message, or a church message. It should be the same message coming from all the organizations, said Lopes. It is by far more important that people get the message rather than the identity of the deliverer of the message. This can sometimes be challenging within the political arena, especially in Washington, D.C., said Lopes.

|

People shop around for information and compare one organization’s message with another. —Rocky Lopes |

Further, he noted that repetition of messages reinforces and inspires action. It is not enough to tell the public once that they need to be prepared and to expect them to be prepared. People engage in verification. If the same message is provided by multiple organizations it becomes more credible to the public (Mileti, 1999). This data suggests a need for the American Red Cross to collaborate with other organizations and a need to ensure consistent messaging. Even though the American Red Cross is not a scientific organization, it relies on science from other organizations and translates that knowledge into meaningful information for the public. The Red Cross collaborates with the National Disaster Education Coalition (NDEC), which is composed of 21 federal agencies and national nonprofit organizations. Prior to September 11, 2001, NDEC consisted of only eight organizations: the Red Cross, FEMA, Weather Service, USGS, National Fire Protection Association, International Association of Emergency Managers, Institute of Business and Home Safety, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Extension Service. Subsequent to the September 2001 events, more organizations became involved because of the need to make the messages more consis-

tent. The organizations meet monthly, catalog their information, validate it through research and publish it on the web site www.disastereducation.org, as well as through the web sites of the Red Cross, FEMA, NOAA, and others. The information available on the web sites is designed for those who communicate with the public: educators, web site designers, brochure writers, news-letter article writers, and others. The information can be tailored depending on the target group because the more local and relevant it is made, the more likely it is to get a response from the public and to build public capacity, noted Lopes.

|

If the same message is provided by multiple organizations it becomes more credible. —Rocky Lopes |

Thus, the most critical thing in building the capacity among the public is to provide information consistently. When the information is put out in a variety of venues, many people will put it to use, thereby reducing the potential for death, injury, and property damage in all types of future disasters, concluded Lopes.

DISPLACED CHILDREN AND THE COMMUNITY

When emergency planners review different emergency scenarios, they usually base their scenarios on adult, educated, healthy people. These plans, however, may not be useful for socially vulnerable groups such as the handicapped, immobile elderly, immigrants with limited English skills, or children during disasters, said J. R. Thomas of the Emergency Management Office in Franklin County, Ohio. Thomas used issues that related to children during a disaster of large proportions to begin a discussion of the complexity of ensuring that the needs of these socially vulnerable groups are met.

|

Children cannot be treated as small adults because their age, cognitive skills, and comprehension of the surroundings is different. —J. R. Thomas |

Children are a particularly vulnerable population. They may be able to walk and talk, but they cannot be treated as small adults because their age, cognitive skills, and comprehension of the surroundings are different. There are many challenges that emergency planners must consider in situations involving children. To ensure that children’s medical, legal, physical, and psychological needs are met, these issues need to be discussed and planned for in advance, said Thomas.

Medical Issues

Under ideal circumstances, if a child has a medical emergency, he or she goes to a local children’s hospital where a pediatrician examines them. However, in the case of a disaster there may be more than 1,000 children admitted to a hospital in a day and not all of them will be able to go to a children’s hospital. Some will need to go to a regular emergency department to be treated. This may be problematic because the regular emergency department may not have adequate equipment for children, noted Thomas. For example, a typical respirator as well as some surgical tools will not work for a child. Emergency medical services and urgent care centers will need to have better access to child size equipment.

Physical Issues

Further, if a child is lost, a police officer takes him or her to Children’s Services and Children’s Services find them temporary housing. During a disaster, because of the large number of displaced children, it may take several days before a placement is found for all the children in need of housing. During those several days the children will need personal hygiene equipment and nutrients; small children may need diapers and formula. Decisions may need to be made as to whether it is better to have 50 children in a gymnasium or to have 20 children in a room in somebody’s house, noted Thomas. Temporary placement in a foster home might be a better solution than putting children in a shelter, but then social services may be unable to find foster homes for large numbers of children. An emergency management office needs to be cognizant of the facts that other things have to take place in a situation where people, especially children, need to be moved and it is very important to think of this process now and not wait until it becomes an actual situation, said Thomas.

Legal Issues

Housing for a significant number of displaced children may result in legal implications, especially when normal processes and access to information may be disrupted. Parents need to know where to look for their child in case of an emergency displacement, while local officials will need to define the parameters for transferring legal custody. If 1,000 children have to be placed somewhere, emergency planners and people responsible for the children’s safety need to know if the person who comes to pick them up is really a next of kin, or some-body who has legal authority, for example, a custodial parent. Another legal issue is whether it is permissible to release a child to a non-custodial parent without a court order. If a child is picked up by someone other than a parent, that person would need an approval and their background would need to be checked as well. However, it is almost impossible to have a court hearing for each indi-

vidual case if there are 50 or more children in question, and it is hard to decide whether a probate court, a juvenile court, or a magistrate’s court should process the cases. Furthermore, if children have to be moved out of a downtown area, and a courtroom is closed, emergency planners need to think of where a hearing would be held and whether it would be possible to set up courtrooms in convention centers or other large venues, noted Thomas. The judicial systems will need to have contingency plans in place to provide expeditious handling of cases and to determine when flexibility of legal standards should be explored.

Psychological Issues

Emergency planners need to think about mental health capabilities as well as long-term care in case of post-traumatic stress disorder in children. It is very traumatic for a child to lose a parent or both parents in an incident, and it is essential that emergency management departments find a way to coordinate social workers, pediatric psychologists and, if needed, psychiatrists to help children in distress, noted Thomas.

Thomas concluded by stating that the ultimate goal of every emergency management organization is to reunite children with their parents or relatives as quickly as possible. Therefore, communication between organizations that handle emergency situations is very important. Organizations such as NGOs and government agencies need to work together and plan ahead to identify the areas where children in distress are going to be taken; they need to ensure that transportation is available and that children are accounted for, concluded Thomas.

WRAP-UP

The discussions of the workshop were quite sobering on the health issues and other challenges that the United States and other countries face during a time of disaster. As destructive as natural disasters such as tornados are, they can be addressed because their intrinsic hazards do not change from disaster to disaster. Terrorist events, however, are difficult to prepare for and defend against because terrorists can change their method of operations. Therefore, an integration of disciplines, especially for public health and emergency responders, needs to be in place in order to meet the challenges and to be effective during a time of crisis, noted Bernard Goldstein, Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh.

As the United States continues to plan for responding to disasters, research and training must guide the effort. Many people believe that once a terrorist event is concluded, the threat from terrorism is reduced. This is a misconception because there are likely to be more terrorist attacks in the future. In order to keep up with potential threats, emergency planners have to focus on training. The

field will also have to be able to systematically evaluate their response with better tools, asserted Goldstein.

Communication was a central theme during the workshop, and ranged from communication capacity at the local level to the need for more research communication. During the workshop, communication at the national level was emphasized; however, Goldstein noted that the majority of people in the country obtain most of their information from local sources. People do not turn to CNN or the CDC, but rather to the local health commissioner and the local TV and radio stations for information.

Local health departments are traditionally very small in the United States. Often, during a time of crisis, a local health department is busy attending to the health needs of affected people and does not have the time to develop an effective communication strategy. Goldstein suggested that there is a great need for a communication surge capacity and to have knowledgeable people to answer the phone, as well as to ensure that messages are consistent for the media and the public.

Additionally, there is a need for more work on the science of communication, observed Goldstein. There is a pervasive belief that if one has the right information, then everyone will understand the risk and take the right action. CDC is therefore emphasizing the necessity for more research in risk communication that would provide a better understanding of how various groups process messages from the scientific community.

The second theme during the workshop was the call for building capacity, which will have to occur through partnerships between NGOs and the government, public and private sector organizations, and federal and local entities. Goldstein emphasized the critical partnership between federal and local governments because in the United States people rely heavily on local government. In contrast to some European countries such as France, the United States takes a decentralized approach to emergency management, with local management in charge during times of disaster. This is not likely to change, so it is important to find ways to strengthen the local/federal partnership and increase intergovernmental cooperation.

Goldstein concluded that, despite all the challenges we face, it is obvious that we have come a long way toward preparing for disasters since September 11. Yet we have so much further to go. Additional progress will not be easy; but it is reassuring that we know so much more today than we did before.