5

Diagnosing Cancer

“The key to a continued reduction in mortality is early detection and accurate diagnosis made in a cost-effective manner.”

Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Guidelines

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2004

“Decisions regarding adequacy of surgical resection, need for adjuvant therapy, and appropriate surveillance protocols are often predicated on tumor characteristics and propensity for disease recurrence. Ambiguity or underreporting of important pathologic features may adversely influence clinical outcomes.”

Quality of Colon Carcinoma Pathology Reporting: A Process of Care Study

Wei et al., 2004

Whatever Georgia may achieve by expanding cancer screening and early detection could be compromised if the state fails to adequately address the next stages in the continuum of cancer care—diagnosis and treatment. Cancer diagnosis is the critical first step in ascertaining the tumor biology or characteristics and extent of disease, as well as in determining the optimal clinical strategy for combating the disease. Several aspects of the diagnostic process are fundamental to quality cancer care: (1) the timely gathering of appropriate diagnostic and surgical specimens for histological assessment, (2) clear, reliable, and standardized pathology reporting on surgical specimens, and (3) documenting the stage of disease before initiating treatment.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee recommends that the Georgia Cancer Coalition (GCC) adopt 14 quality measures related to

|

BOX 5-1 Adequacy of Diagnostic and Surgical Specimens

Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Surgical Specimens

Documentation of Cancer Pathologic Stage Before Chemotherapy or Radiation Treatment Begins

|

cancer diagnosis (Box 5-1). The first five measures will help Georgia ensure that adequate diagnostic and surgical specimens are available for timely, pathologic assessment or evaluation of breast and colorectal cancers. The next five measures can be used by Georgia to track the quality of the pathology reports on cancer surgical specimens, which clinicians depend on to assess the extent of the cancer and to advise patients on treatment options. The final set of four measures will help the state ensure adequate treatment planning by monitoring whether health care providers document patients’ cancer stage before initiating chemotherapy or radiation treatment.

The 14 recommended quality measures pertaining to cancer diagnosis are discussed further below. For each measure discussed, there is a section providing a brief rationale for the selection of the measure, explanation of the evidence underlying the measure (the “consensus on care”) and a description of what is known about the gap between the evidence and current practice (“knowledge vs. practice”). Also provided near the end of the chapter is a brief section on the potential data sources for measures in

the diagnostic domain. The chapter concludes with summaries of each quality measure.

RECOMMENDED MEASURES FOR TRACKING THE QUALITY OF CANCER DIAGNOSIS

Adequacy of Diagnostic and Surgical Specimens

Two of the five recommended quality-of-cancer-care measures related to the adequacy of diagnostic and surgical specimens pertain to the use of biopsies in breast cancer diagnosis. During a breast biopsy, either a small sample of suspicious breast tissue (i.e., an incisional core biopsy) or an entire lump or suspicious area is removed (i.e., an excisional biopsy) for histological assessment. When the tissue sample is removed with a needle, the procedure is referred to as a needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration. To track the timeliness of biopsy after a suspicious, abnormal mammogram and the use of needle biopsy before breast cancer surgery, the committee recommends that Georgia adopt the following measures:

-

Measure 5-1—Timely breast cancer biopsy—the proportion of women who receive a biopsy within 14 days after first documentation of a category 4 or 5 abnormal mammogram.

-

Measure 5-2—Use of needle biopsy in breast cancer diagnosis—the proportion of women who have a needle biopsy of the breast at least 1 day prior to breast cancer surgery.

The remaining three measures pertain to the collection and histological assessment or evaluation of surgical specimens taken from patients who undergo surgery for breast or colorectal cancer. To monitor the appropriate collection and histological assessment or evaluation of breast and colorectal cancer surgical specimens, the committee recommends that the GCC adopt the following measures:

-

Measure 5-3—Tumor-free surgical margins in breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer—the proportion of patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery whose surgical margins are free of tumor after the last surgical procedure.

-

Measure 5-4—Appropriate histological assessment of breast cancer—the proportion of Stage I and Stage II breast cancer cases with sentinel node biopsy or with histological assessment of 10 or more axillary lymph nodes.

-

Measure 5-5—Appropriate histological assessment of colorectal cancer—the proportion of colorectal cancer surgery patients with documented histological assessment of 12 or more lymph nodes.

The rationale for the IOM committee’s decision to recommend each of these measures is discussed further below.

Breast Cancer Biopsies

The first two recommended quality-of-cancer-care measures pertaining to the adequacy of diagnostic and surgical specimens are the timeliness of biopsy after a suspicious, abnormal mammogram and the use of needle biopsy before breast cancer surgery. A strong evidence base shows that screening mammography reduces breast cancer deaths by finding cancer at an early, treatable stage (USPSTF, 2002).1 Mammography can only improve breast cancer outcomes, however, if follow-up of abnormal findings is timely and appropriate. Screening mammography findings should be documented according to the Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS) (Box 5-2). Women with abnormalities that are suspicious or suggestive of malignancy—BI-RADS categories 4 and 5—should be followed up with a biopsy according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) breast screening and diagnosis guidelines (ACR, 2003; NCCN, 2004c).

Timely breast cancer biopsy.

Consensus on care. There is no consensus on the ideal interval between finding a category 4 or 5 abnormal mammogram and the follow-up biopsy; however, the available evidence suggests that the interval should be brief (Olivotto et al., 2001). The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends that the biopsy be completed in less than 14 days after first documentation of a category 4 or 5 mammogram; RAND, Inc. recommends no more than 6 weeks (Gifford and Schmidt, 2000; ICSI, 2003). Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is associated with later stage at diagnosis and poorer prognosis. A recent, multivariate analysis of 4,465 women with invasive breast cancer suggests that 6- to 12-month delays to diagnosis of asymptomatic breast cancer are associated with increased risk of lymph node metastases and larger tumor size (Olivotto et al., 2002).

Timeliness is a basic attribute of high-quality health care (IOM, 2001). The IOM committee feels strongly that women with suspicious or highly suggestive abnormal mammograms should not have to wait longer than 14 days for a biopsy. Delays in diagnosis are associated with substantial anxiety and distress for the patient (IOM, 2004).

Knowledge vs. practice. The proportion of women who have a needle biopsy before breast cancer surgery is not known. There are only limited

|

1 |

See Chapter 4, Detecting Cancer Early, for further discussion of breast cancer screening. |

|

BOX 5-2 Breast abnormalities that are identified through screening mammography are categorized according to a taxonomy established by the American College of Radiology in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the American Medical Association, the American College of Surgeons, and the College of American Pathologists. The six BI-RADS reporting categories represent gradations of the likelihood that a cancer exists, from lowest to highest probability.

SOURCE: ACR, 2003. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. |

data on the extent of delays in follow-up biopsies after a suspicious mammogram. Studies assessing follow-up of all types of cancer screening indicate that about 25 percent of patients with a suspicious finding do not receive needed follow-up care (Yabroff et al., 2003). Racial and ethnic minorities, as well as uninsured and low-income persons, are especially at risk. A 2001 survey of medical directors of community health centers in 10 states found that about 40 percent of uninsured patients had difficulty getting specialty referrals, including referrals for follow-up of abnormal screening tests (Gusmano et al., 2002).

Use of needle biopsy in breast cancer diagnosis.

Consensus on care. NCCN recommends that breast tissue samples be obtained by needle biopsy if feasible (NCCN, 2004c). Needle biopsy is preferred because it is quick, accurate, and less invasive, and produces a better cosmetic outcome than alternative approaches do (Liberman, 2000; Morrow et al., 2001; Collins et al., 2004; Baxter et al., 2004; NCCN, 2004c). Needle biopsy techniques include core needle biopsy, vacuum-assisted biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration. The biopsy may be performed with or without image guidance depending on the location of the lesion, its visibility at ultrasound, equipment availability, and radiologist’s expertise. For about 10 to 20 percent of women, however, a needle biopsy is not technically feasible because of the location and nature of their breast lesion (NCCN, 2004c). Thus, a standard of 70 to 80 percent rather than 100 percent would be appropriate.

Knowledge vs. practice. Data on the use of needle biopsy before breast cancer surgery are not available.

Cancer Surgical Specimens

Three of the recommended quality measures pertain to the collection and histological assessment or evaluation of surgical specimens taken from patients who undergo surgery for breast or colorectal cancer.

One measure is the proportion of breast cancer surgery patients whose surgical margins are free of tumor after the last surgical procedure. The histological assessment of surgical margins is fundamental to cancer diagnosis (Bland et al., 1999; Stocchi et al., 2001; Weir et al., 2002; Trocha and Giuliano, 2003; Le Voyer et al., 2003; Compton, 2003; Krag and Single, 2003; Fitzgibbons et al., 2004). The outer edge of the surgical specimen—referred to as the surgical margin—is considered free of tumor if there is no tumor at the line of resection. If the margin contains cancer or is too small to be fully analyzed, the extent of the patient’s cancer may be underestimated and undertreated.

The other two measures pertain to the histological assessment of lymph nodes in patients with breast cancer or colorectal cancer. Lymph node evaluation is central to determining the stage of cancer at diagnosis. About one-third of persons have metastases detected at the time of their first cancer diagnosis (Eyre et al., 2002). If a cancer spreads, the lymph nodes are usually affected. In breast cancer, the axillary (armpit) nodes are the main passageway that cancer cells use to spread to other parts of the body. In colorectal cancer, the regional lymph nodes are the main passageway.

Consensus on care.

Tumor free-breast cancer surgical margins. The goal of breast cancer surgery is to completely remove the tumor and to obtain clear surgical margins. There is extensive evidence that positive surgical margins are associated with significant morbidity and cost, including higher rates of local tumor recurrence and further surgical or medical treatment (Silverstein et al., 1999; Fredriksson et al., 2003; NCCN, 2004b). With lumpectomy, a positive margin often leads to additional surgery with either re-excision of additional tissue at the positive margin, or total mastectomy. If it is not possible to obtain a negative margin with re-excision, then mastectomy is usually required, although it may be appropriate to treat cases with a microscopic focally-positive margin with breast conservation by increasing the dose of a radiation therapy boost (NCCN, 2004b). NCCN guidelines indicate that while margins greater than 1 centimeter are “widely accepted” as negative, such margin width may be excessive causing a less acceptable cosmetic result. Margins less than 1 millimeter are considered inadequate. However, the NCCN guidelines state that data are insufficient to make definitive statements about margins between 1 and 10 mm.

Assessment of lymph nodes after breast cancer surgery. Histological assessment of axillary nodes is critical to diagnosing Stage I and II breast cancer and to determining the appropriate course of treatment (Weir et al., 2002; Fitzgibbons et al., 2004; NCCN, 2004b). In Stage I breast cancer, the tumor is less than 2 centimeters in diameter with no spread beyond the breast (axillary nodes are clear). In Stage II, the tumor is 2 to 5 centimeters in size or the tumor has spread to the axillary nodes (Box 5-3). Several studies suggest that examining an insufficient number of lymph nodes leads to poorer survival after breast cancer surgery (Bland et al., 1998; Bland et al., 1999; Weir et al., 2002; Krag and Single, 2003). If too few nodes are removed, the patient’s cancer may be understaged and thus undertreated. NCCN guidelines recommend two options: (1) dissection of 10 or more axillary lymph nodes for histological assessment or (2) sentinel node biopsy for patients with unicentric tumors smaller than 5 centimeters with no prior treatment or large excisions if an experienced sentinel lymph node team is available (NCCN, 2004b). Either procedure may be optional in patients who have particularly favorable tumors, patients for whom the selection of adjuvant systemic therapy is unlikely to be affected, elderly patients, and patients with serious comorbid conditions.

Assessment of lymph nodes after colorectal cancer surgery. Most colorectal cancer patients undergo surgical resection—an estimated 92 percent of colon cancer patients and 84 percent of rectal cancer patients (Compton, 2003). Diagnosing the extent of colorectal cancer requires histological assessment of the regional lymph nodes that are retrieved during surgery. There is an extensive literature showing that survival of colorectal

|

BOX 5-3

NOTE: TNM = Tumor, Node, Metastasis. SOURCE: American Joint Committee on Cancer (Greene et al., 2002); NCCN Breast Cancer (NCCN, 2004b). |

cancer increases with the number of recovered lymph nodes, regardless of the number of positive nodes that are found (Stocchi et al., 2001; Le Voyer et al., 2003; Compton, 2003). While there is no consensus on the specific number of nodes that should be analyzed, the range in the recommendations is small. For example, NCCN advises at least 14 nodes, while the College of American Pathologists (CAP) advises at least 12 nodes and urges that additional techniques such as visual enhancement be considered if fewer than 12 nodes are found (Compton, 2004a, NCCN, 2004f).

Knowledge vs. practice. It is difficult to discern from the available research whether shortcomings in pathology data are due to poor documentation

practices or poor surgical technique. Most research on the collection of breast cancer and colorectal cancer surgical specimens has focused on reporting practices rather than the adequacy of the specimens themselves. However, there is evidence that older women are less likely than younger women to undergo an axillary node dissection despite clinical guidelines to the contrary (Malin et al., 2002).

Numerous studies indicate that surgical and pathology reporting practices are of variable quality and, in fact, information on margins and the number and status of nodes is often missing from pathology reports (Weir et al., 2002; Imperato et al., 2002; Compton, 2003; White et al., 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2004). Stocchi et al. (2001) examined the surgery and pathology reports of 673 patients who were enrolled in a U.S. cooperative group clinical trial for Stage II or III rectal cancer. The researchers found that the operative and pathology notes were poorer than expected; 18 percent of patients had fewer than five lymph nodes examined and 68 percent had fewer than 12 nodes examined.

Adequacy of Pathology Reporting on Cancer Surgical Specimens

The IOM committee recommends five quality measures to monitor the adequacy of pathology reports on cancer surgical specimens. The first measure tracks pathology laboratories’ compliance with the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer reporting standards for breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers.

-

Measure 5-6—Pathology laboratories’ compliance with reporting standards for cancer surgical specimens—the proportion of pathology laboratories that report CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer.

The remaining four measures track whether pathology reports include the key data elements currently mandated by the Commission on Cancer for breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers:

-

Measure 5-7—Adequacy of pathology reports on breast cancer surgical specimens—the proportion of pathology reports on invasive breast cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer.

-

Measure 5-8—Adequacy of pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens—the proportion of pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer.

-

Measure 5-9—Adequacy of pathology reports on lung cancer surgical specimens—the proportion of pathology reports on invasive lung cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer.

-

Measure 5-10—Adequacy of pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens—the proportion of pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer.

The rationale for the IOM committee’s decision to recommend each of these measures is discussed further below.

Consensus on Care

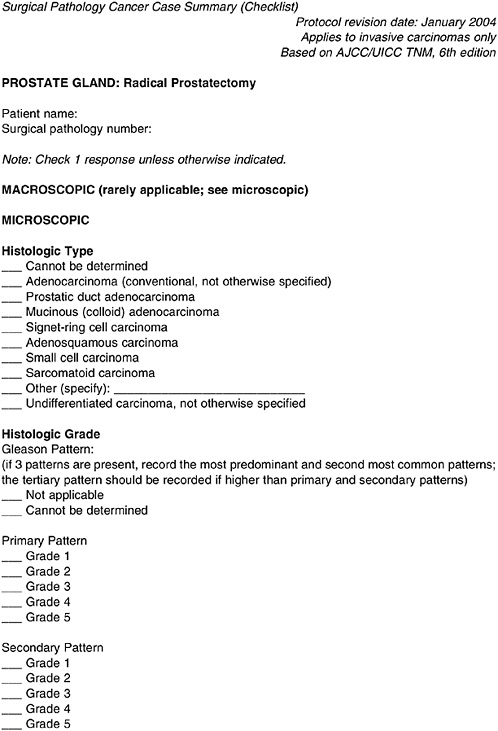

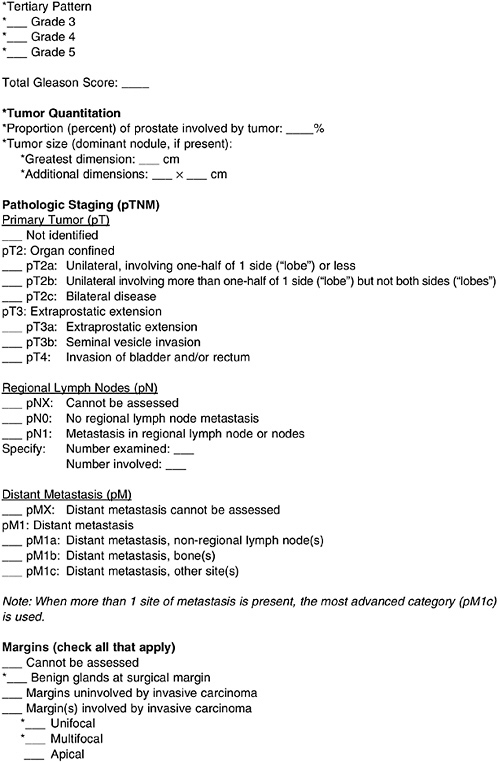

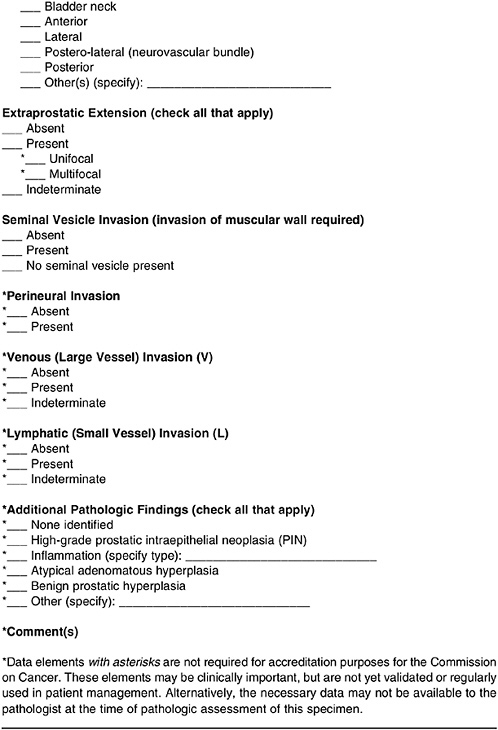

Pathologists examine surgical specimens to identify the tumor size, histology, and other tumor characteristics—findings that are needed to properly stage the disease, to formulate treatment decisions, and to determine prognosis. The pathology report communicates these findings to the clinician. It is essential that the report is clear and comprehensive. Traditionally, pathologists have used an unstructured, narrative style to complete their reports. Research in the last decade has suggested, however, that standardized reporting templates yield more comprehensive and readable information than free-text pathology reports (Appleton et al., 1998; Cross et al., 1998; Branston et al., 2002). In response, CAP has developed a set of reporting templates, called checklists, for reporting pathology findings for cancer specimens (CAP, 2003). There is a specific checklist for each tumor site and type of surgical specimen. CAP recommends, but does not require, that its certified laboratories use the checklist.

As of 2004, the Commission on Cancer, a multidisciplinary program of the American College of Surgeons, has required that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-certified cancer centers report the scientifically validated data elements in the CAP checklists for cancer-directed surgical specimens. The CAP checklist itself is optional. The mandatory data elements include the histologic type and grade, pathologic staging including distant metastasis, margins and lymph nodes, and other cancer-specific data items (Gal et al., 2004; Srigley et al., 2004; Fitzgibbons et al., 2004; Compton, 2004a).

Figure 5-1 illustrates the data elements required by the Commission on Cancer in a pathology report on a prostate cancer specimen. Only cancer-directed surgical resection specimens must meet the Commission on Cancer’s requirement to report the scientifically validated data elements in the CAP checklists; cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resections are exempt (Paxton, 2004). In 2005, the Commission on Cancer will begin auditing its certified pathology laboratories to ensure that they comply with

the mandate to report the scientifically validated data elements for surgical specimens.

Knowledge vs. Practice

Pathology laboratories’ compliance with reporting standards for cancer surgical specimens. The quality of pathology reporting in Georgia has not been studied. There are 39 Commission on Cancer-approved cancer programs in Georgia (Table 5-1). Presumably, once the Commission on Cancer reporting mandate is fully enforced, it will improve pathology reporting at these Georgia institutions. Numerous studies have documented generally poor compliance with guidelines on reporting cancer-related pathology findings (Weir et al., 2002; Malin et al., 2002; Imperato et al., 2002; IOM, 2003; Compton, 2003; White et al., 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2004). Recent evidence indicates that the quality of cancer-related pathology reporting has improved since the problems were first identified in the mid- to late-1980s.

Adequacy of pathology reports on breast cancer surgical specimens. Researchers assessed concordance with breast cancer pathology reporting guidelines in 1998 and 1999 at the Roswell Park Cancer Center, a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. One hundred patient records were reviewed and most lacked at least one required data element. Only 77 percent of the breast surgery reports documented margin status (Wilkinson et al., 2003). An earlier study of breast pathology reporting by hospitals in New York state found wide variation in quality (Imperato et al., 2002). Overall, performance was less than 70 percent on 9 of 16 data elements, including tumor margin status. Distance to closest margin was reported in 69 percent of the cases, but the margin orientation was noted in only 25 percent. A large-scale national study of 7,097 women who underwent lumpectomy in 1994, found significant variation in the content of pathology reports (White et al., 2003). Substantial proportions of the reports were missing key pathologic data, including lymph node invasion (46 percent), ductal carcinoma in situ (43 percent), and macroscopic margin (27 percent). The researchers found that geographic location and type of cancer program were important predictors of compliance with reporting standards; women who were treated in the Midwest or by a community hospital were the most likely to have incomplete records.

Adequacy of pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens. Although data are limited, there are studies showing considerable variability in colorectal cancer pathology reporting including failure to document critical data. There is also evidence that the quality of colorectal cancer

TABLE 5-1 Cancer Programs in Georgia That Are Certified by the Commission on Cancer

|

Institution Name |

City |

Institution Name |

City |

|

Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital |

Albany |

Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center |

Fort Gordon |

|

Sumter Regional Hospital |

Americus |

Northeast Georgia Medical Center |

Gainesville |

|

Athens Regional Medical Center |

Athens |

Spalding Regional Medical Center |

Griffin |

|

Atlanta Medical Center |

Atlanta |

West Georgia Health System |

LaGrange |

|

Emory Crawford Long Hospital |

Atlanta |

Gwinnett Hospital System |

Lawrenceville |

|

Emory University Hospital |

Atlanta |

Coliseum Medical Centers |

Macon |

|

Northside Hospital |

Atlanta |

Medical Center of Central Georgia |

Macon |

|

Piedmont Hospital |

Atlanta |

WellStar Health System |

Marietta |

|

Saint Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta |

Atlanta |

WellStar Kennestone Hospital |

Marietta |

|

Medical College of GA Hospital & Clinics |

Augusta |

Southern Regional Medical Center |

Riverdale |

|

University Health Care System |

Augusta |

Floyd Medical Center |

Rome |

|

VA Medical Center |

Augusta |

Redmond Regional Medical Center |

Rome |

|

WellStar Cobb Hospital |

Austell |

Memorial Health |

Savannah |

|

Southeast Georgia Regional MC |

Brunswick |

St. Joseph’s/Candler Health System |

Savannah |

|

The Medical Center |

Columbus |

Emory Eastside Medical Center |

Snellville |

|

Rockdale Medical Center |

Conyers |

Henry Medical Center |

Stockbridge |

|

Hamilton Medical Center |

Dalton |

John D. Archbold Memorial Hospital |

Thomasville |

|

DeKalb Medical Center |

Decatur |

Tift Regional Medical Center |

Tifton |

|

VA Medical Center |

Decatur |

South Georgia Medical Center |

Valdosta |

|

South Fulton Medical Center |

East Point |

|

|

|

SOURCE: American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACoS CoC, 2005). |

|||

pathology reports varies with a laboratory’s affiliation and hospital case volume. Wei et al. studied the pathology records of 438 North Carolina patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 1997 and 2000 (Wei et al., 2004). Compared with contract pathology labs and community hospitals, high-volume hospitals and teaching facilities were more likely to report recommended pathology data including macroscopic depth of penetration and margin status.

Adequacy of pathology reports on lung cancer surgical specimens. Surgical resection is the primary treatment for lung cancer (NCCN, 2004d). Few studies have been done on the quality of pathology reporting for lung cancer specimens. A 1991 CAP study of pathology reports of lung cancer resection specimens found poor documentation of some key data elements. Venous invasion was reported in only 22.6 percent of cases and regional lymph nodes were described in 74.7 percent of the reports (Gephardt and Baker, 1996).

Adequacy of pathology reports on prostate cancer specimens. Radical prostatectomy was the primary treatment for an estimated 41 percent of prostate cancer patients from 1995 to 2003 (Cooperberg et al., 2004). Little is known about the quality of pathology reports on prostate surgical specimens.

Documentation of Cancer Pathologic Stage Before Chemotherapy or Radiation Treatment Begins

Cancer stage describes the extent and severity of an individual’s cancer. The stage of a cancer is determined by a number of diagnostic factors, including location of the primary tumor, tumor size, regional lymph node involvement, cell type and tumor grade, and presence or absence of distant metastasis (Greene et al., 2002). Cancer staging information is the most important indicator of a patient’s prognosis (Bland et al., 1999; Stocchi et al., 2001; Weir et al., 2002; Trocha and Giuliano, 2003; Le Voyer et al., 2003; Krag and Single, 2003; Compton, 2003; Fitzgibbons et al., 2004; Compton, 2004b). Information about the stage of a cancer patient’s cancer gives clinicians a roadmap for determining a patient’s treatment options. It also helps cancer patients understand the extent of their disease, their prognosis, and their treatment choices (Brierley et al., 2002; Compton, 2004b).

Cancer stage may be referred to as clinical or pathologic depending on the timing. Clinical stage is based on what has been learned about a patient’s cancer through, for example, physical exams, imaging tests, biopsies, and blood tests—up to the time of initial definitive treatment which is often surgery (NCI, 2005). Pathologic stage combines the clinical staging infor-

mation with surgical findings, incorporating data not only from before the initial definitive treatment but also from pathologic examination of resected primary and regional lymph nodes.

In addition to being important for the provision of treatment to individual patients, stage data are essential to building a sound infrastructure for cancer research, quality improvement, and population cancer control. Stage data are basic inputs to tumor registries; to evaluating screening and early detection programs, treatment interventions, and quality improvement efforts; to developing, implementing, and monitoring clinical guidelines; and to identifying patients who might benefit from a clinical trial; and to computing survival statistics (Chamberlain et al., 2000; Brierley et al., 2002; Woodward et al., 2003; Compton, 2004b). Clearly, clinical outcomes can be understood only in the context of the stage of the disease.

The IOM committee recommends that the GCC adopt four quality measures to help Georgia ensure that patients’ cancers are appropriately staged before chemotherapy or radiation treatment begins:

-

Measure 5-11—Breast cancer stage determined before treatment—the proportion of new breast cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated.

-

Measure 5-12—Colorectal cancer stage determined before treatment—the proportion of new colorectal cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated.

-

Measure 5-13—Lung cancer stage determined before treatment—the proportion of new lung cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated.

-

Measure 5-14—Prostate cancer stage determined before treatment—the proportion of new prostate cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated.

The rationale for the IOM committee’s decision to recommend these measures is discussed further below.

Consensus on Care

Every cancer patient’s treatment regimen should be tailored to his or her stage of disease. Most treatment guidelines cannot be followed until the tumor stage has been determined (ASCO, 2002; ACR, 2004; NCCN, 2004a). Chemotherapy and radiation treatment of most cancers, including breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers, should not be initiated until

the pathologic stage has been determined and documented in the medical record (NCCN, 2004a).2

Knowledge vs. Practice

Little is known about the extent to which cancer treatment is initiated before the stage has been determined and documented. Likewise, little is known about the completeness of staging or its documentation. Nonetheless, a plethora of evidence documenting serious underreporting of pathology information suggests that many cancer patients are treated in advance of, or in the absence of, appropriate documentation of the stage of their disease (Weir et al., 2002; Imperato et al., 2002; White et al., 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2004; Compton, 2004b).

DATA SOURCES

The data for 12 of the 14 measures pertaining to quality of cancer diagnosis must be abstracted from pathology reports and medical records (Table 5-2). Data for the remaining two measures—measures 5-1 (timely breast cancer diagnosis) and 5-2 (use of needle biopsy in breast cancer diagnosis)—can be drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare dataset and might also be in a mammography registry (should Georgia develop one). Further information about the strengths and weakness of data sources is presented in Chapter 2, Concepts, Methods, and Data Sources, and Appendix A.

SUMMARY

Accurate and timely diagnosis is basic to combating cancer and is the essential first step in quality care. If diagnostic practice is poor, treatment and outcomes are likely to be less than optimal. A substantial body of research has documented that the process of cancer diagnosis in the United States is often incomplete and inadequately documented. This situation probably exists in Georgia as well, although specific evidence is not currently available. If Georgia is to meaningfully improve cancer outcomes for its residents, it must address the conduct of cancer diagnosis statewide. This chapter has recommended 14 quality measures that GCC should use to gauge its progress in ensuring that cancer treatment in Georgia draws from comprehensive and clearly documented diagnostic and histological records.

TABLE 5-2 Potential Data Sources for Recommended Measures of the Quality of Cancer Diagnosis in Georgiaa

|

Quality Measure |

Potential Georgia-Based Data Sources |

Potential National Data Sources for Benchmarking and Comparison |

|||||||

|

GCCR and Georgia SEER |

Georgia mammography registry |

Georgia SEER/Medicare |

Medical records |

CoC |

BCSC |

CAP |

SEER |

SEER/Medicare |

|

|

Biopsy after abnormal mammogram |

|

|

|

|

|

● |

|

|

● |

|

Breast needle biopsy |

|

|

|

|

|

● |

|

|

● |

|

Breast cancer surgical margins |

|

|

|

|

● |

|

● |

|

|

|

Histological assessment of lymph nodes |

|

|

|

|

● |

|

|

● |

|

|

Pathology reporting |

|

|

|

|

● |

|

● |

|

|

|

Cancer stage determined before treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

aSee Chapter 2, Concepts, Methods, and Data Sources, and Appendixes A and B for descriptions of data sources. NOTE: GCCR = Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry; BCSC = Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; CoC = American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer; CAP = College of American Pathologists. The symbol ● indicates data are currently available. The symbol |

|||||||||

QUALITY MEASURE SPECIFICATIONS: DIAGNOSING CANCER

The following section contains summary descriptions of the quality indicators presented in this chapter. These quality indicators were drawn from a variety of clinical practice setting organizations, federal programs, provider groups, and other sources. See Appendix A for descriptions of each of these organizations, including their classification schemes for grading clinical recommendations and characterizing evidence.

|

Measure 5-1. |

Timely Breast Cancer Biopsy |

|

Measure 5-2. |

Use of Needle Biopsy in Breast Cancer Diagnosis |

|

Measure 5-3. |

Tumor-Free Surgical Margins in Breast-Conserving Surgery |

|

Measure 5-4. |

Appropriate Histological Assessment of Breast Cancer |

|

Measure 5-5. |

Appropriate Histological Assessment of Colorectal Cancer |

|

Measure 5-6. |

Pathology Laboratories’ Compliance with Reporting Standards For Cancer Surgical Specimens |

|

Measure 5-7. |

Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Breast Cancer Surgical Specimens |

|

Measure 5-8. |

Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Colorectal Cancer Surgical Specimens |

|

Measure 5-9. |

Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Lung Cancer Surgical Specimens |

|

Measure 5-10. |

Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Prostate Cancer Surgical Specimens |

|

Measure 5-11. |

Breast Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment |

|

Measure 5-12. |

Colorectal Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment |

|

Measure 5-13. |

Lung Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment |

|

Measure 5-14. |

Prostate Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment |

MEASURE 5-1: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Timely Breast Cancer Biopsy

|

Description |

Timely breast cancer biopsy after a category 4 or 5 abnormal mammogram |

|

Source |

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, RAND, Vermont Cancer Center |

|

Consensus on care |

There is no consensus on the ideal interval between an abnormal mammogram and confirmed diagnosis. Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is associated with later stage at diagnosis and poorer prognosis. A recent, multivariate analysis of 4,465 women with invasive breast cancer suggests that 6- to 12-month delays to diagnosis of asymptomatic breast cancer are associated with increased risk of lymph node metastases and larger tumor size. Delays are also associated with significant anxiety for the patient. Timeliness is fundamental to high-quality health care. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Data on delays in follow-up of abnormal mammograms are limited. Most studies indicate that follow-up rates after abnormal mammogram, in general, fall below 75 percent. High rates of advanced disease at diagnosis persist among some groups—especially for racial minorities, uninsured, and low-income persons, suggesting that follow-up after an abnormal screening may be a problem. A 2001 survey of medical directors of community health centers in 10 states found that about 40 percent of uninsured patients had difficulty getting specialty referrals, including referrals for follow-up of abnormal screening tests. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of women who have a completed biopsy within 14 days after first documentation of a category 4 or 5 abnormal mammogram (see comments below) |

|

Denominator |

Number of women with a category 4 or 5 abnormal mammogram |

|

Potential data sources(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)/ Medicare dataset; Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry (with enhancements); mammography registry |

|

Comments |

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category 4 and 5 mammograms are suspicious or highly suggestive of malignancy, respectively. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; SEER/Medicare dataset |

|

Key references |

Gifford D, Schmidt L. 2000. Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. In: Asch, et al. Quality of Care for Oncologic Conditions and HIV. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Pp. 33-45. Gusmano MK, et al. 2002. Exploring the limits of the safety net: community health centers and care for the uninsured. Health Affairs (Millwood). 21(6): 188-94. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. 2003. Health Care Guideline: Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. 10th edition. [Online] Available: http://www.icsi.org/Knowledge/detail.asp?catID-298itemID-154 [accessed 2004]. Littenberg B, et al. 2003. Methodologic Issues in Measuring the Quality of Cancer Care in the Community. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. Olivotto IA, et al. 2002. Influence of delay to diagnosis on prognostic indicators of screen-detected breast carcinoma. Cancer. 94(8): 2143-2150. Yabroff KR, et al. 2003. Is the promise of cancer-screening programs being compromised? Quality of follow-up care after abnormal screening results. Med Care Res Rev. 60(3): 294-331. |

MEASURE 5-2: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Use of Needle Biopsy in Breast Cancer Diagnosis

|

Description |

Needle biopsy is performed before breast cancer surgery |

|

Source |

American College of Surgeons; Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) |

|

Consensus on care |

Needle biopsy is the NCCN-preferred diagnostic follow-up to an abnormal mammogram (Category 2a recommendation). Needle biopsy is preferred because it is quick, accurate, and less invasive than the alternative approach (i.e., needle localization excisional biopsy). Needle biopsies often save patients an additional surgical procedure and thus reduce cost and improve quality of life. Women who undergo needle biopsy and ultimately opt for reconstruction after breast cancer surgery often have a better cosmetic outcome because the biopsy avoids an incision and scarring. Note that for 10 to 20 percent of women with abnormal mammograms, needle biopsy is not technically feasible because of the location and nature of the lesion. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Unknown |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of women who have a needle biopsy of the breast at least 1 day prior to breast cancer surgery |

|

Denominator |

Number of women who undergo breast cancer surgery |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)/ Medicare dataset; mammography registry |

|

Comments |

Measurement goal should be 80 to 90 percent (some breast lesions are not amenable to needle biopsy). Needle biopsy techniques include core needle biopsy, vacuum-assisted biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration. The biopsy may be performed with or without image guidance depending on the location of the lesion, its visibility at ultrasound, equipment availability, and radiologist’s expertise. The equipment for stereotactic biopsy is costly and may not be available throughout Georgia. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

SEER/Medicare dataset; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium |

|

Key references |

Collins LC, et al. 2004. Diagnostic agreement in the evaluation of image-guided breast core needle biopsies: results from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Surg Pathol. 28(1): 126-31. CSI. 2003. Health Care Guideline: Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. 10th edition. [[Online] Available: http://www.icsi.org/Knowledge/detail.asp?catID-298itemID-154 [accessed 2004]. Liberman L. 2000. Centennial dissertation: Percutaneous imaging-guided core breast biopsy: State of the art at the millennium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 174(ES): 1191-9. Morrow, et al. 2001. Prospective comparison of stereotactic core biopsy and surgical excision as diagnostic procedures for breast cancer patients. Ann Surg. 233(4): 537-41. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v.1.2004. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Guidelines. |

MEASURE 5-3: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Tumor-Free Surgical Margins in Breast-Conserving Surgery

|

Description |

Tumor-free surgical margins in breast-conserving surgery |

|

Source |

College of American Pathologists (CAP); American College of Surgeons |

|

Consensus on care |

The goal of breast-conserving cancer surgery is to completely remove the tumor and to obtain clear surgical margins. Positive margins with breast-conserving surgery result in higher rates of local tumor recurrence. With lumpectomy, a positive margin often leads to additional surgery with either re-excision of additional tissue at the positive margin, or total mastectomy. Assuring appropriate treatment of breast cancer depends on high-quality pathology, including analyses of surgical margins. CAP guidelines require reporting gross margin status of all surgical margins. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

There are numerous reports that clear surgical margins are often lacking or that related documentation is missing from patient records. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of breast-conserving cancer surgery patients whose surgical margins are free of tumor after their last surgical procedure |

|

Denominator |

Number of breast-conserving cancer surgery patients |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies of pathology reports and medical records. |

|

Comments |

Clear surgical margin is defined as no tumor at the line of resection. Measurement goal should be 100 percent. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

CAP; baseline special studies |

|

Key references |

Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Fitzgibbons PL, et al. (CAP). 2004. Breast: Protocol applies to all invasive carcinomas of the breast. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/breast04_pw.pdf [accessed August 30, 2004]. Imperato PJ, et al. 2002. Breast cancer pathology practices among Medicare patients undergoing unilateral extended simple mastectomy. J Womens Health Gender Based Med. 11(6): 537-47. Silverstein MJ, et al. 1999. The influence of margin width on local control of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. New Engl J Med. 340(19): 1455-61. White J, et al. 2003. Compliance with breast-conservation standards for patients with early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 97:893-904. Wilkinson NW, et al. 2003. Concordance with breast cancer pathology reporting practice guidelines. J Am Coll Surg. 196:38-43. |

MEASURE 5-4: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Appropriate Histological Assessment of Breast Cancer

|

Description |

Appropriate histological assessment of Stage I and Stage II breast cancer |

|

Source |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN); Vermont Cancer Center |

|

Consensus on care |

Axillary lymph node status is a critical factor in determining the appropriate treatment for Stage I and II breast cancer. The axillary (armpit) lymph nodes are the main passageway that breast cancer cells use to spread to other parts of the body. Removing too few nodes may lead to undertreatment. NCCN guidelines emphasize that 10 or more axillary lymph nodes should be provided for histological assessment (Category 2a recommendation). Numerous studies show that survival markedly improves with the number nodes that are assessed. Sentinel node biopsy is an acceptable alternative to axillary dissection in some patients with unicentric tumors smaller than 5 cm with no prior treatment or large excisions if an experienced sentinel lymph node team is available. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Numerous studies have documented that histological assessments are not performed as recommended and that use declines with patients’ age. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of Stage I and Stage II breast cancer cases with sentinel node biopsy or with histological assessment of 10 or more axillary lymph nodes |

|

Denominator |

Number of Stage I and Stage II breast cancer cases |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER); Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry (GCCR); pathology reports and medical records |

|

Comments |

NCCN guidelines indicate that axillary dissection or sentinel node biopsy may be optional in patients who have particularly favorable tumors, patients for whom the selection of adjuvant systemic therapy is unlikely to be affected, elderly patients, and patients with serious comorbid conditions. Thus, the goal for this measure should be less than 100 percent. Stage I refers to tumors less than 2 cm in diameter with no spread beyond the breast. Stage II includes tumors 2 to 5 cm in size with or without lymph node involvement, tumors less than 2 cm with spread to axillary nodes, and tumors greater than 5 cm without spread to axillary nodes. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

SEER; GCCR; baseline studies of pathology reports and medical records |

|

Key references |

Edge SB, et al. 2003. Emergence of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer as standard-of-care in academic comprehensive cancer centers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 95(20):1514-21. Littenberg B, et al. 2003. Methodologic Issues in Measuring the Quality of Cancer Care in the Community. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v.1.2004. Breast Cancer. Trocha SD, Giuliano AE. 2003. Sentinel node in the era of neoadjuvant therapy and locally advanced breast cancer. Surgical Oncology. 12(4): 271-6. Weir L, et al. 2002. Prognostic significance of the number of axillary lymph nodes removed in patients with node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 20(7): 1793-9. |

MEASURE 5-5: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Appropriate Histological Assessment of Colorectal Cancer

|

Description |

Appropriate histological assessment of colorectal cancer |

|

Source |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN); College of American Pathologists (CAP) |

|

Consensus on care |

Histological assessment of regional lymph node status is integral to pathologic staging and treatment of colorectal cancer. There is an extensive literature showing that survival of colorectal cancer increases with the number of recovered lymph nodes, regardless of the number of positive nodes. NCCN recommends that a minimum of 14 regional lymph nodes be removed during surgical resection (Category 2a recommendation). CAP recommends removal of at least 12 nodes and urges that additional techniques (i.e., visual enhancement) be considered if fewer than 12 nodes are found. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Numerous studies indicate that surgical and pathology reporting practices are of variable quality. Information on margins and the number and status of nodes is often missing. In one study, researchers examined the surgery and pathology reports of 673 patients who were enrolled in a U.S. cooperative group clinical trial for Stage II or III rectal cancer; 18 percent of patients had fewer than five lymph nodes examined and 68 percent had fewer than 12 nodes examined. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of colorectal cancer surgery patients with a surgical resection that included at least 12 lymph nodes |

|

Denominator |

Number of colorectal cancer surgery patients |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER); Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry (GCCR) (with enhancements); pathology and surgical reports in medical records |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

SEER; GCCR; baseline studies of pathology reports and medical records. |

|

Key references |

Compton CC. 2003. Colorectal carcinoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and molecular features. Mod Pathol. 16(4):376-88. Compton CC (CAP). 2004. Colon and Rectum: Protocol applies to all invasive carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Carcinoid tumors, lymphomas, sarcomas, and tumors of the vermiform appendix are excluded. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/ColonRectum04_pw.pdf. [accessed September 1, 2004]. Le Voyer TE, et al. 2003. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 21(15): 2912-9. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v.2.2004. Colon Cancer. Stocchi L, et al. 2001. Impact of surgical and pathologic variables in rectal cancer: a United States community and cooperative group report. J Clin Oncol. 19(18): 3895-902. |

MEASURE 5-6: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Pathology Laboratories’ Compliance with Reporting Standards for Cancer Surgical Specimens

|

Description |

Pathology laboratories that report College of American Pathologists (CAP) data elements as required by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer |

|

Source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer |

|

Consensus on care |

Appropriate treatment for solid tumors depends on the pathology of the primary tumor, surrounding tissues, and regional lymph nodes. Clear, standardized, and complete pathology reporting is integral to quality cancer care. CAP has developed detailed templates or “checklists” for reporting findings on cancer specimens. There are specific checklists for each organ site and type of surgical specimen, each with a series of mandatory and optional data elements. The purpose of the checklists is to ensure that information—essential to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment—is always included. The Commission on Cancer mandates that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-approved cancer programs report the mandatory data elements in the CAP checklists for cancer-directed surgical specimens (the CAP checklist reporting format is optional). The Commission on Cancer mandate does not apply to cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resection specimens. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

There are limited data documenting the extent of variation in pathology reporting. Selected studies have assessed reporting of some solid tumor types (e.g., breast, colorectal) and documented generally poor compliance with CAP guidelines. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of pathology laboratories that report all Commission on Cancer-required CAP data elements for cancer specimens |

|

Denominator |

Number of pathology laboratories that assess breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer specimens |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Benchmark source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer; baseline special studies |

|

Key references |

CAP. 2003. Required Data Elements from CAP Cancer Checklists Mandated for Use by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cance, Effective January 1, 2004. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/protocols_intro.html#1 [accessed September 1, 2004]. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Paxton. 2004. Cancer protocols: leaner, later, more lenient. CAP Today. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cap_today/feature_stories0604Cancer_Protocols.html [accessed 2004]. White J, et al. 2003. Compliance with breast-conservation standards for patients with early stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 97(4): 893-904. Wilkinson, NW, et al. 2003. Concordance with breast cancer pathology reporting practice guidelines. J Am Coll Surg. 196(1): 38-43. |

MEASURE 5-7: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Breast Cancer Surgical Specimens

|

Description |

Pathology reports on invasive breast cancer surgical specimens that include College of American Pathologists (CAP) data elements as required by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer |

|

Source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer |

|

Consensus on care |

Appropriate treatment of breast cancer depends on clear, standardized, and comprehensive reporting on the pathology of the primary tumor, surrounding tissues, and regional lymph nodes. CAP has developed a detailed template or “checklist” for reporting findings on invasive breast cancer specimens. The purpose of the checklist is to ensure that information—essential to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment—is always included. The Commission on Cancer mandates that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-approved cancer programs report the scientifically validated data elements in the CAP checklist for cancer-directed surgical specimens (the CAP checklist reporting format is optional). The Commission on Cancer mandate does not apply to cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resection specimens. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Available research indicates that the quality of pathology reports for breast cancer surgical specimens is variable; documentation of key data elements is often poor. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of pathology reports on invasive breast cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer |

|

Denominator |

Number of pathology reports on invasive breast cancer surgical specimens |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies of pathology reports; medical records |

|

Comments |

Measurement goal should be 100 percent. Findings should be reported in the aggregate and individually by pathology laboratory. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

CAP; Commission on Cancer; baseline special studies |

|

Key references |

Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Fitzgibbons, et al. (CAP). 2004. Breast: Protocol applies to all invasive carcinomas of the breast. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/breast04_pw.pdf [accessed August 30, 2004]. Imperato PJ, et al. 2002. Breast cancer pathology practices among Medicare patients undergoing unilateral extended simple mastectomy. J Womens Health Gender Based Med. 11(6): 537-547. White J, et al. 2003. Compliance with breast-conservation standards for patients with early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 97:893-904. Wilkinson NW, et al. 2003. Concordance with breast cancer pathology reporting guidelines. J Am Coll Surg. 196(1): 38-43. |

MEASURE 5-8: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Colorectal Cancer Surgical Specimens

|

Description |

Pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens that include College of American Pathologists (CAP) data elements as required by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer |

|

Source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer |

|

Consensus on care |

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for colorectal cancer and the pathologic characteristics of resection specimens are the most powerful predictors of health outcomes. Complete and accurate pathology reports on surgical specimens are integral to treatment decisions. CAP has developed a detailed template or “checklist” for reporting findings on colorectal cancer specimens. The purpose of the checklist is to ensure that information—essential to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment—is always included. The Commission on Cancer mandates that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-approved cancer programs report the scientifically validated data elements in the CAP checklist for cancer-directed surgical specimens (the CAP checklist reporting format is optional). The Commission on Cancer mandate does not apply to cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resection specimens. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Available research indicates that the quality of pathology reports for colorectal cancer surgical specimens is variable; documentation of key data elements is often poor. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer |

|

Denominator |

Number of pathology reports on colorectal cancer surgical specimens |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies of pathology reports; medical records |

|

Comments |

Measurement goal should be 100 percent. Findings should be reported in the aggregate and individually by pathology laboratory. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

CAP; Commission on Cancer; baseline special studies |

|

Key references |

Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Compton CC. 2003. Colorectal carcinoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and molecular features. Mod Path. 16(4): 376-88. Compton (CAP). 2004. Colon and Rectum: Protocol applies to all invasive carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Carcinoid tumors, lymphomas, sarcomas, and tumors of the vermiform appendix are excluded. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/ColonRectum04_pw.pdf [accessed September 1, 2004]. —COLON and RECTUM: Polypectomy. —RECTUM: Local Excision (Transanal Disk Excision). —COLON AND RECTUM: Resection. Stocchi L, et al. 2001. Impact of surgical and pathologic variables in rectal cancer: a United States community and cooperative group report. J Clin Oncol. 19(18): 3895-902. |

MEASURE 5-9: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Lung Cancer Surgical Specimens

|

Description |

Pathology reports on lung cancer surgical specimens that include College of American Pathologists (CAP) data elements as required by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer |

|

Source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer |

|

Consensus on care |

Surgical resection is the initial treatment for most types of lung cancer. Complete and accurate pathology reports on surgical specimens are integral to treatment decisions. CAP has developed a detailed template or “checklist” for reporting findings on lung cancer specimens. The purpose of the checklist is to ensure that information—essential to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment—is always included. The Commission on Cancer mandates that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-approved cancer centers report the mandatory data elements in the CAP checklist for cancer-directed surgical specimens (the CAP checklist reporting format is optional). The Commission on Cancer mandate does not apply to cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resection specimens. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Available research indicates that the quality of pathology reports for lung cancer surgical specimens is variable; documentation of key data elements is often poor. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of pathology reports on lung cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements as required by the Commission on Cancer |

|

Denominator |

Number of pathology reports on lung cancer surgical specimens |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies of pathology reports; medical records |

|

Comments |

Measurement goal should be 100 percent. Findings should be reported in the aggregate and individually by pathology laboratory. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

CAP; Commission on Cancer; baseline special studies |

|

Key references |

Chamberlain DW, et al. 2000. Pathological examination and the reporting of lung cancer specimens. Clin Lung Cancer. 1(4): 261-8. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Gal AA, et al. (CAP). 2004. Lung: Protocol applies to all invasive carcinomas of the lung. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/lung04_pw.pdf [acccessed September 1, 2004]. Gephardt GW, Baker PB. 1996. Lung carcinoma surgical pathology report adequacy: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of over 8300 cases from 464 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 120(10): 922-7. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Small Cell Lung Cancer. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. |

MEASURE 5-10: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Adequacy of Pathology Reports on Prostate Cancer Surgical Specimens

|

Description |

Pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens that include College of American Pathologists (CAP) data elements as required by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer |

|

Source |

CAP; Commission on Cancer |

|

Consensus on care |

A large proportion of prostate cancer patients are treated surgically. Appropriate follow-up to prostate cancer surgery depends on clear, standardized, and comprehensive reporting on the pathology of the primary tumor, surrounding tissues, and regional lymph nodes. CAP has developed a detailed template or “checklist” for reporting findings on prostate cancer specimens. The purpose of the checklist is to ensure that information—essential to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment—is always included. The Commission on Cancer mandates that pathology laboratories at Commission on Cancer-approved cancer programs report the scientifically validated data elements in the CAP checklist for cancer-directed surgical specimens (the CAP checklist reporting format is optional). The Commission on Cancer mandate does not apply to cytologic specimens, diagnostic biopsies, and palliative resection specimens. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Little is known about the quality of pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens that include CAP data elements are required by the Commission on Cancer |

|

Denominator |

Number of pathology reports on prostate cancer surgical specimens |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Special studies of pathology reports; medical records |

|

Comments |

Measurement goal should be 100 percent. Findings should be reported in the aggregate and individually by pathology laboratory. |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

CAP; Commission on Cancer; baseline studies of pathology reports |

|

Key references |

Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards, 2004. Standard 4.6. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Prostate Cancer. Srigley JR, et al. (CAP). 2004. Prostate Gland: Protocol applies to invasive carcinomas of the prostate gland. [Online] Available: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/cancer_protocols/prostate04_pw.pdf [accessed September 1, 2004]. —PROSTATE GLAND: Radical prostatectomy —PROSTATE GLAND: Needle Biopsy, transurethral prostatic resection, enucleation specimen. |

MEASURE 5-11: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Breast Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment

|

Description |

Breast cancer cases in which pathologic staging preceded chemotherapy and radiation treatment |

|

Source |

American College of Surgeons; American College of Radiology; American Society of Clinical Oncology; National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

|

Consensus on care |

Chemotherapy and radiation treatment of breast cancer should not be initiated until the pathologic stage has been determined and documented in the medical record. Clinical stage is based on what has been learned about a patient’s cancer up to the time of initial definitive treatment. Pathologic stage combines clinical staging information with surgical findings, incorporating pathologic examination of resected primary and regional lymph nodes. Every cancer patient’s treatment regimen should be tailored to his or her stage of disease. Most treatment guidelines cannot be followed until the tumor stage has been determined. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Few studies have reported on documentation of cancer stage before treatment. The proportion of Georgia women with breast cancer that is treated before the stage is determined is not known. Baxter et al. (2004) analyzed more than 25,000 breast cancer patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ from 1992 through 1999. The researchers found that tumor grade was not documented in the charts of more than half of the cases. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new breast cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated |

|

Denominator |

Number of new breast cancer cases with chemotherapy or radiation treatment |

|

Data source |

Medical records |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Baseline studies of medical records |

|

Key references |

ACR (American College of Radiology). 1999. ACR Practice Guideline for Communication: Radiation Oncology. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/dyna/?doc=departments/stand_accred/standards/standards.html [accessed 2004]. Baxter NN, et al. 2004. Trends in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 96(6): 443-8. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards 2004. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Greene FL, et al. (AJCC). 2002. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Breast Cancer. |

MEASURE 5-12: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Colorectal Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment

|

Description |

Colorectal cancer cases in which pathologic staging preceded chemotherapy and radiation treatment. |

|

Source |

American College of Radiology; American Society of Clinical Oncology; Commission on Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

|

Consensus on care |

Chemotherapy or radiation treatment of colorectal cancer should not be initiated until pathologic stage has been determined and documented in the medical record. Clinical stage is based on what has been learned about a patient’s cancer up to the time of initial definitive treatment. Pathologic stage combines clinical staging information with surgical findings, incorporating pathologic examination of resected primary and regional lymph nodes. Every cancer patient’s treatment regimen should be tailored to his or her stage of disease. Most treatment guidelines cannot be followed until the tumor stage has been determined. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Few studies have reported on documentation of stage of colorectal cancer before treatment. The proportion of Georgians with colorectal cancer that is treated before the stage is determined is not known. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new colorectal cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation is initiated |

|

Denominator |

Number of new colorectal cancer cases with chemotherapy or radiation treatment |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Medical records |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Baseline studies of medical records |

|

Key references |

ACR (American College of Radiology). 1999. ACR Practice Guideline for Communication: Radiation Oncology. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/dyna/?doc=departments/stand_accred/standards/standards.html [accessed 2004]. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards 2004. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Compton CC. 2004. Pathologic staging of colorectal cancer. An advanced users’ guide. Pathology Case Reviews 9(4): 150-62. Greene FL, et al. (AJCC). 2002. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.2.2004. Colon Cancer. |

MEASURE 5-13: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Lung Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment

|

Description |

Lung cancer cases in which pathologic staging preceded chemotherapy and radiation treatment |

|

Source |

American College of Radiology; American Society of Clinical Oncology; Commission on Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

|

Consensus on care |

Chemotherapy or radiation treatment of lung cancer should not be initiated until the pathologic stage has been determined and documented in the medical record. Clinical stage is based on what has been learned about a patient’s cancer up to the time of initial definitive treatment. Pathologic stage combines clinical staging information with surgical findings, incorporating pathologic examination of resected primary and regional lymph nodes. Every cancer patient’s treatment regimen should be tailored to his or her stage of disease. Most treatment guidelines cannot be followed until the tumor stage has been determined. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Few studies have reported on documentation of lung cancer stage before treatment. The proportion of Georgians with lung cancer that is treated before the stage is determined is not known. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new lung cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated |

|

Denominator |

Number of new lung cancer cases with chemotherapy or radiation treatment |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Medical records |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Baseline studies of medical records |

|

Key references |

ACR. 1999. ACR Practice Guideline for Communication: Radiation Oncology. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/dyna/?doc=departments/stand_accred/standards/standards.html [accessed 2004]. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards 2004. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. GCCR. 2004. Georgia Cancer Cases by Stage at Diagnosis 1999-2000. Unpublished data. Greene FL, et al. (AJCC). 2002. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. |

MEASURE 5-14: DIAGNOSING CANCER—Prostate Cancer Stage Determined Before Treatment

|

Description |

Prostate cancer cases in which pathologic staging preceded chemotherapy and radiation treatment |

|

Source |

American College of Radiology; American Society of Clinical Oncology; Commission on Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

|

Consensus on care |

Chemotherapy and radiation treatment of prostate cancer should not be initiated until the pathologic stage has been determined and documented in the medical record. Clinical stage is based on what has been learned about a patient’s cancer up to the time of initial definitive treatment. Pathologic stage combines clinical staging information with surgical findings, incorporating pathologic examination of resected primary and regional lymph nodes. Every cancer patient’s treatment regimen should be tailored to his or her stage of disease. Most treatment guidelines cannot be followed until the tumor stage has been determined. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Few studies have reported on documentation of prostate cancer stage before treatment. The proportion of Georgians with prostate cancer that is treated before the stage is determined is not known. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new prostate cancer cases with medical chart documentation of pathologic stage before chemotherapy or radiation treatment is initiated |

|

Denominator |

Number of new prostate cancer cases with chemotherapy or radiation treatment |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Medical records |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

— |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Baseline studies of medical records |

|

Key references |

ACR. 1999. ACR Practice Guideline for Communication: Radiation Oncology. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/dyna/?doc=departments/stand_accred/standards/standards.html [accessed 2004]. Commission on Cancer. 2003. Cancer Program Standards 2004. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons. [Online] Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards.pdf. Cooperberg MR, et al. 2004. The contemporary management of prostate cancer in the United States: lessons from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor (CAPSURE), a national disease registry. J Urol. 171:1393-401. NCCN. 2004. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2004. Prostate Cancer. |

REFERENCES

ACoS CoC (American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer). 2005. Search. [Online] Available: http://web.facs.org/cpm/CPMApprovedHospitals_Search.htm [accessed January 6, 2005].

ACR (American College of Radiology). 1999. ACR Practice Guideline for Communication: Radiation Oncology. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/dyna/?doc=departments/stand_accred/standards/standards.html [accessed 2004].

——. 2003. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) Mammography. Reston, VA: ACR.

——. 2004. Guidelines and Standards. [Online] Available: http://www.acr.org/s_acr/sec.asp?CID=1848&DID=16053 [accessed November 29, 2004].

Appleton MA, Douglas-Jones AG, Morgan JM. 1998. Evidence of effectiveness of clinical audit in improving histopathology reporting standards of mastectomy specimens. J Clin Pathol. 51(1): 30-3.

ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology). 2002. Practice Guidelines. [Online] Available: http://www.asco.org/ac/1,1003,_12-002009,00.asp [accessed November 29, 2004].