2

Shaping the Flow of International Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars: Visa and Immigration Policy

The advancement of modern science and engineering (S&E) requires dynamic functioning of professional networks of colleagues, mentors, and students. Scientific research is now an international endeavor, so these collegial networks must also be international. E-mail and inexpensive telephony have raised international communication to a new level of convenience, but personal interaction continues to be the sine qua non of collaboration and innovation. The healthy functioning of research networks depends on participants’ ability to travel across borders and to work and study in other countries.1

The free flow of knowledge and people, however, sometimes conflicts with the short-term national interests of states. There is a tenuous balance between protecting information important to national security interests and the sharing of knowledge that may produce scientific and technologic advances for the common good. Technical knowledge can be used for nefarious purposes, as well as for good, and modern terrorists have adapted their own forms of networking and knowledge dissemination. In an age of terrorism, attempts to limit the misuse of technical knowledge must be as sophisticated and international as science itself. The United States, like other nations, now struggles to balance the need to protect technical infor-

mation against the need to maintain the openness of scholarship on which its culture, economy, and security depend.

A growing challenge for policy makers is to maintain the flow of people and information to the extent compatible with security needs. This chapter provides a brief picture of how difficult that has become and how easily the modern cross-currents of policies and regulations, particularly those governing visas and immigration, can disrupt the global movement and therefore the productivity of scientists and engineers. The issuance and monitoring of visas may be as important as the education and training experience.

The repercussions that followed the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, have included security-related changes in federal visa and immigration policy. The changes were intended to restrict the illegal movements of an extremely small population, but they have had a substantial effect on international graduate students and postdoctoral scholars already in the United States or contemplating a period of study here. Other immigration-related policies relevant to international student flows are international reciprocity agreements, deemed export policies, and specific acts that grant special or immigrant status to groups of students or high-skill workers, such as the Chinese Student Protection Act of 1992, and the policies enacted shortly after the end of the Cold War to allow scientists and engineers of the former Soviet Union to enter the United States (see Table 2-1).

Recently, the policy environment has favored heightened security. The security environment in turn has had adverse implications for perceptions of the United States as a desirable destination for study and for international scientific gatherings.

NONIMMIGRANT VISA POLICIES AND PROCEDURES

The Immigration and Nationality Act has served as the primary body of law governing immigration and visa operations since 1952.2 It was amended by the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). DHS subsumed the activities of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and of several other entities. The act gave the Department of State (DOS) sole responsibility for vetting and issuing documents for travel into the United States and made DHS responsible for setting visa policy and for overseeing the activities of persons once they arrive in the United States. Both agencies coordinate with the Federal

TABLE 2-1 Legislation Affecting Visas and Study Plans

|

Laws |

Executive Orders, Advisories, and Directives |

Consequences |

|

1952 Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) |

Primary body of law governing immigration and visa operations |

|

|

1954 International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) |

Technology Alert List (TAL) |

|

|

Deemed Export Controls |

|

|

|

1979 Export Administration Regulations (EAR) |

Controls export of commodities of commercial interest |

|

|

1992 Chinese Student Protection Act |

Provided eligibility for US permanent residency to Chinese students and scholars studying in the United States in 1989, at the time of the Tiananmen Square uprising. |

|

|

1994 Foreign Relations Security Act |

Holds consular officials liable if terrorists obtain a visa |

|

|

1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act |

Defines criminal penalties for consular misconduct; created Coordinated Interagency Partnerships Regulating International Students (CIPRIS), the predecessor to SEVIS |

|

|

VISAS Mantis Implemented in 1998 under authority of INA§212(a)(3)(A)(i)(II) governing illegal technology transfer |

Consolidation of several Cold War-era nationality-based screening programs, including CHINEX for PRC nationals and SPLEX for USSR and Eastern Europe nationals; uses TAL to screen visa applicants to guard against the export of sensitive goods, technology, and information. |

|

Laws |

Executive Orders, Advisories, and Directives |

Consequences |

|

2001 Patriot Act |

|

Created SEVIS and US-VISIT concept |

|

2002 Homeland Security Act |

|

Created DHS; split authority for visas and immigration. DOS vets and issues documents, DHS handles policy and enforcement |

|

2002 Enhanced Border Security And Visa Entry Reform Act (BSA) |

|

Imposed border control (INS) on DHS Mandated increased requirements for US-VISIT program integration, interoperability with other law-enforcement and intelligence systems, biometrics, and accessibility |

|

|

VISAS Condor Implemented January 2002 BSA §306 |

Security screen for nationals of US-designated state sponsor of terrorism |

|

|

Biometric Visa Program Began implementation September 2003 BSA §303 |

All visa applicants must have personal interview with consular official, scan fingerprints, and submit a photograph |

|

|

Machine-Readable Passports (MRPs) for Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Countries (September 2005) |

All VWP countries must implement MRPs incorporating biometric identifiers; nationals from VWP countries that do not issue such passports need to obtain a visa for US travel for visas issued after September 2005 |

|

BOX 2-1 F-1: An alien having a residence in a foreign country which he has no intention of abandoning, who is a bona fide student qualified to pursue a full course of study and who seeks to enter the United States temporarily and solely for the purpose of pursuing such a course of study consistent with section 214(l) at an established college, university, seminary, conservatory, academic high school, elementary school, or other academic institution or in a language training program in the United States, particularly designated by him and approved by the Attorney General after consultation with the Secretary of Education, which institution or place of study shall have agreed to report to the Attorney General the termination of attendance of each nonimmigrant student, and if any such institution of learning or place of study fails to make reports promptly the approval shall be withdrawn. [INA § 101(a) (15)(F)(i)] J-1: An alien having a residence in a foreign country which he has no intention of abandoning, who is a bona fide student, scholar, trainee, teacher, professor, research assistant, specialist, or leader in a field of specialized knowledge or skill, or other person of similar description, who is coming temporarily to the United States as a participant in a program designated by the Director of the United States Information Agency, for the purpose of teaching, instructing or lecturing, studying, observing, conducting research, consulting, demonstrating special skills, or receiving training and who, if he is coming to the United States to participate in a program under which he will receive graduate medical education or training, also meets the requirements of section 212(j), and the alien spouse and minor children of any such alien if accompanying him or following to join him. [INA §101(a)(15)(J)(i)] H-1b: An alien subject to section 212(j)(2), who is coming temporarily to the United States to perform services … in a specialty occupation described in section 214(i)(1) …. [INA § 101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b)] |

Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Justice, and other entities to meet security requirements.

Over the years, a veritable alphabet soup of visa classes has been created, but there are no classes specific to graduate students or postdoctoral scholars. Which visa is used often depends on where students are in their course of graduate study, how long they have been in the United States, and, for postdoctoral scholars, in which sector they are performing research—a national laboratory, a university, or an industrial setting. Most international graduate students and postdoctoral scholars who visit the United States do so using temporary nonimmigrant visas that cover educa-

|

B-1: An alien (other than one coming for the purpose of study or of performing skilled or unskilled labor or as a representative of foreign press, radio, film, or other foreign information media coming to engage in such vocation) having a residence in a foreign country which he has no intention of abandoning and who is visiting the United States temporarily for business or temporarily for pleasure. Enrollment in a course of study is prohibited. An alien who is admitted as, or changes status to, a B-1 or B-2 nonimmigrant on or after April 12, 2002, or who files a request to extend the period of authorized stay in B-1 or B-2 nonimmigrant status on or after such date, violates the conditions of his or her B-1 or B-2 status if the alien enrolls in a course of study. Such an alien who desires to enroll in a course of study must either obtain an F-1 or M-1 nonimmigrant visa from a consular officer abroad and seek readmission to the United States, or apply for and obtain a change of status under section 248 of the Act and 8 CFR part 248. The alien may not enroll in the course of study until the Service has admitted the alien as an F-1 or M-1 nonimmigrant or has approved the alien’s application under part 248 of this chapter and changed the alien’s status to that of an F-1 or M-1 nonimmigrant. (Added 4/12/02; 67 FR 18062). 214b: Every alien (other than a nonimmigrant described in subparagraph (L) or (V) of section 101(a)(15), and other than a nonimmigrant described in any provision of section 101(a)(15)(H)(i) except subclause (b1) of such section) shall be presumed to be an immigrant until he establishes to the satisfaction of the consular officer, at the time of application for a visa, and the immigration officers, at the time of application for admission, that he is entitled to a nonimmigrant status under section 101(a)(15). An alien who is an officer or employee of any foreign government or of any international organization entitled to enjoy privileges, exemptions, and immunities under the International Organizations Immunities Act [22 U.S.C. 288], or an alien who is the attendant, servant, employee, or member of the immediate family of any such alien shall not be entitled to apply for or receive an immigrant visa, or to enter the United States as an immigrant unless he executes a written waiver in the same form and substance as is prescribed by section 247(b). [INA ACT 214(b)]

|

tional activities: F-class (“student”) and J-class (“exchange visitor”) visas for most graduate students, and J-class or, less often, H-1b (“specialty worker”) visas for postdoctoral scholars (see Box 2-1).3 Some graduate students and postdoctoral scholars are admitted on other types of visas, including O, J-2, TN, and EA visas.4 In addition, graduate students and

|

3 |

The H-1b population, although important, is largely distinct from the graduate student and postdoctoral populations and is not a major focus of this report; see brief section in Chapter 3. |

|

4 |

Philip Chen, senior adviser to the Deputy Director for Intramural Research, National Institutes of Health, presentation to committee, October 12, 2004. |

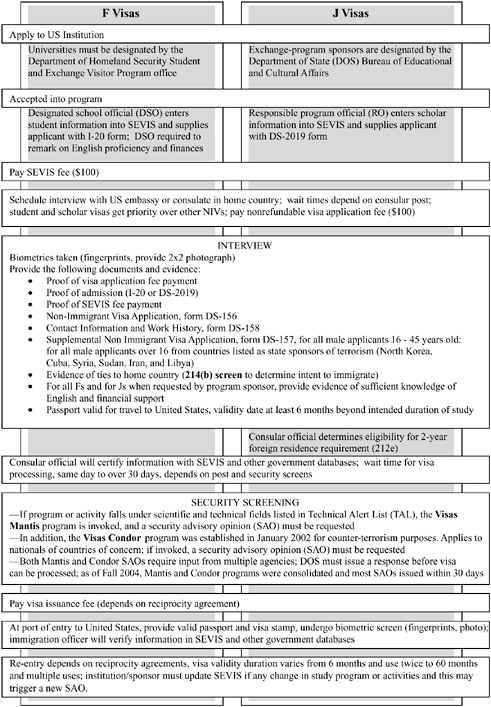

postdoctoral scholars who come to the United States for scientific meetings or short-term research collaborations that do not require university enrollment are admitted on B-1 visas, generally considered “business” visas. The process by which graduate students and postdoctoral scholars apply for F and J visas is outlined in Figure 2-1.

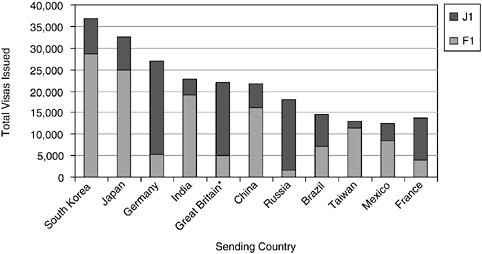

In 2003, for F and J visa classes, the primary sending country was South Korea, followed by Japan, Germany, India, and Great Britain (see Figure 2-2). One can see a clear regional difference: European countries send more J-class or exchange visitors, and Asian countries send more F-class or student visitors. The largest numbers of J-visa visitors come from Germany, followed by Great Britain, Russia, France, and Brazil. The largest numbers of F-visa visitors come from South Korea, followed by Japan, India, China, Taiwan, and Mexico. To give a sense of scale, of the 27,849,443 nonimmigrant visitors in 2003, 20,142,909 were tourists, 4,215,714 were temporary business visitors, some 939,216 (3.4 percent) were students and exchange visitors (F-1 and J-1 visa classes), and 360,498 (1.3 percent) were specialty occupation workers and trainees (H-1b visa class).5

Although it is tempting to use those issuance numbers as a measure of undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral inflow, it is not advisable inasmuch as visa classes contain a heterogeneous mix of people. F-class visas include students from high school through graduate school. J-class visas include graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, au pairs, camp counselors, short-term international faculty visitors, and others (see footnote to Figure 2-3). And, not all visa issuances lead to travel and enrollment.

9-11 and Its Aftermath

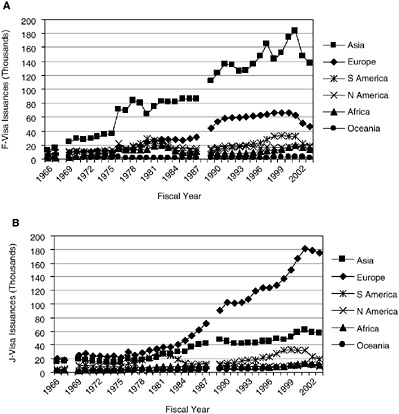

Several clear trends can be seen in visa issuances in recent years (Figure 2-3). F-visa issuances showed a strong, long-term upward trend from 1966 through the end of the century. The downturn for Asia in the middle 1990s reflected the adoption of the Chinese Student Protection Act of 1992, which made thousands of Chinese students enrolled in US institutions in 1989 (at the time of the Tiananmen Square uprising) eligible for permanent residence on July 1, 1993. Currency exchange rates have had a substantial impact on stipends, cost of living, and travel expenses for international students. A steep decline in visa issuances began in 2001, and continued

|

5 |

Office of Immigration Statistics, “Table 24. Nonimmigrants admitted by class of admission: Selected fiscal years 1981-2003”, 2003 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Office of Immigration Statistics, Office of Management, Department of Homeland Security, 2003. Available at http://uscis.gov/graphics/shared/aboutus/statistics/TEMP03yrbk/TEMPExcel/Table24D.xls. |

FIGURE 2-2 Top 11 student- and scholar-sending countries, FY 2003.

SOURCE: Data provided by US Department of State and available in its annual publication Report of the Visa Office, published by the Bureau of Consular Affairs. Recent editions are available at http://travel.state.gov/visa/report.html. (*) Note that Great Britain issuance numbers include UK and Hong Kong.

through 2003. J-visa issuances, mostly to Europeans, followed roughly the same pattern, with a larger rise in the 1990s and a smaller downturn after 2001. To date, the downturn has reflected an increased denial rate more than a decreased application rate. As seen in Figure 2-4, the refusal rate for J-visa applicants rose steadily from 2000 through 2003. The adjusted refusal rate for F-visa applicants peaked in 2002. In 2004, denial rates had decreased considerably and were approaching 1999 levels.6 It is not possible to obtain visa denial rates by country.

One can track the changes in nonimmigrant-visa issuance rates directly to changes in visa and immigration policies and structures after the terror attacks of 9-11. Implementation of the student-tracking system, the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) and enhanced Visas Mantis security screening led to closer scrutiny and longer times for visa processing. The effects of the increased security were felt keenly by newly accepted and continuing students, who with university researchers and administrators expressed dismay at the new degree of difficulty in obtaining

|

6 |

US Department of State, Immigrant Visa Control and Reporting Division, 1998-2003. See Figure 2-4. |

FIGURE 2-3 Visa issuance volumes by region for F and J classes, 1966-2003.

SOURCES: Data provided by US Department of State and are from its annual publication, Report of the Visa Office, published by the Bureau of Consular Affairs. Recent editions are available at http://travel.state.gov/visa/report.html. No regional data were available for 1968 or 1988. Regions are as defined by Department of State. North America includes Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. Hong Kong statistics are reported with UK. Before 1992, Europe statistics included USSR. In FY 1992, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan statistics are reported with Asia; and Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine are reported with Europe.

F and J visa classes were not broken into subclasses until 1984. Data reported here are for all F and all J visas issued. F visas are for students in secondary (high-school) and postsecondary education. J visas are in two categories: Private Sector (foreign physician, au pair, camp counselor, summer work/travel, and trainee) and Government Programs (postsecondary student, college/university student, professor, research scholar, short-term scholar, specialist, teacher, government visitor, and international visitor). Additional subclasses are for spouses and dependents of primary applicants.

FIGURE 2-4 Visa workloads and refusals: student and exchange visitors.

SOURCE: Data provided by US Department of State and available in its annual publication Report of the Visa Office, published by the Bureau of Consular Affairs. Recent editions are available at http://travel.state.gov/visa/report.html. The adjusted refusal rate is calculated with the following formula: (Refusals - Refusals Overcome/Waived)/(Issuances + Refusals - Refusals Overcome/Waived).

a visa to study in the United States.7 In addition, US-based scientific and engineering meetings, conferences, and oversight groups were canceled or unable to go on as planned.8

The European press is filled with stories of scholars from China and Muslim countries who were denied re-entry into the United States after brief trips abroad.9 The press reports concerns about the nontransparent visa application process and seemingly arbitrary visa rejections, again with examples of scholars from non-EU countries.10 In addition to laments about long delays in obtaining US visas, reports cite rude behavior and long waiting times at US embassies for Asian, Muslim, and European students and scholars.11 The press is also alarmed that the SEVIS tracking system is akin to parole monitoring for common criminals.12 In combination, those factors have led to a feeling among Europeans that they are “not welcome in the United States.”

The Student and Exhange Visitor Information System (SEVIS)

September 11 accelerated implementation of SEVIS. Mandated by the Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, SEVIS

became the responsibility of DHS in 2003. It is administered by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Division and began collecting student-admissions and postdoctoral-appointment data in summer 2003. By July 2004, SEVIS had approved 773,000 student and exchange visitors to study in the United States (F-1, M-1, and J-1 visa categories) and 118,000 of their dependents. It had certified 8,737 schools of many types, from universities to pet-grooming and flight schools, and was receiving about 30 additional requests for certification per day.13 Despite early challenges14 and some initial technical difficulties, the system was said to be functioning reasonably well at the time of the present committee’s investigation.15

SEVIS is both criticized and praised for its role in tracking foreign students once in the United States to verify that they are pursuing their intended courses of study at certified institutions. SEVIS adds a layer of verification not previously available by allowing embassy and consular officers to electronically verify the validity of the I-20 form of a student applicant or the DS-2019 form of an exchange-visitor applicant. The I-20 is provided by a US learning institution to document that a student has been accepted into a course of study; the DS-2019 is provided by a US exchange-visitor program to verify that a graduate student or postdoctoral scholar has been accepted into a designated exchange program (see Figure 2-1).

On September 1, 2004, DHS implemented a $100 fee to help defray the cost of the program, despite criticism that the fee places a substantial burden on students from poor countries. The nonrefundable fee must be paid by all F-1, J-1, and M-1 applicants before they apply for an entrance visa and is not refundable if the visa is not issued.16 The regular visa fee also is not refundable if the visa is declined. There are no data that indicate whether students have been deterred by the $100 fee from applying

|

13 |

Susan Geary, deputy director for the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), Department of Homeland Security, presentation to committee, July 19, 2004. The number of approved schools has now exceeded 9,000. |

|

14 |

Nicholas Confessore. 2002. “Borderline insanity.” Washington Monthly. Confessore writes about the politics behind implementation of the Coordinated Interagency Partnerships Regulating International Students (CIPRIS), the predecessor to SEVIS. |

|

15 |

Government Accountability Office. 2004. Performance of Information System to Monitor Foreign Student and Exchange Visitors Has Improved, but Issues Remain. Washington, DC: GAO (GAO-04-690); Government Accountability Office. 2005. Border Security: Streamlined Visas Mantis Program Has Lowered Burden on Foreign Science Students and Scholars, but Further Refinements Needed (GAO-05-198). Washington, DC: GAO; Kelly Field. 2005. “Visa delays stemming from scholar’s security clearances are down since last year, report says.” The Chronicle of Higher Education (February 18); Joe Pouliot. 2005. “Boehlert praises improvements to visa processes.” House Science Committee Press Office, Washington, DC (February 13). |

|

16 |

See the Web site of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement at http://www.ice.gov. |

for US visas, but some US universities now compensate accepted students for the amount of the fee.

Visas Mantis and Condor

Visas Mantis and Visas Condor programs are intended to provide additional scrutiny for visitors who may pose a security risk. The Visas Mantis process17 is triggered when a student or exchange-visitor applicant intends to study a subject covered by the Technology Alert List (TAL). The TAL was originally drawn up as a tool for preventing proliferation of weapons technology and was later applied by embassy and consular officials when reviewing student visa applications. The express purpose of the TAL is to prevent the export of “goods, technology, or sensitive information” through such activities as “graduate-level studies, teaching, conducting research, participating in exchange programs, receiving training or employment.”18 If flagged by Mantis, a nonimmigrant-visa application requires a security advisory opinion (SAO), which may involve input from several federal agencies. Initially, Mantis procedures were applied on entry and each re-entry to the United States for persons studying or working in sensitive fields. In 2004, SAO clearance was extended to 1 year for those who were returning to a US government-sponsored program or activity and performing the same duties or functions at the same facility or organization that was the basis for the original Mantis authorization.19 In 2005, the US Department of State extended the validity of Mantis clearances for F, J, H, L, and B visa categories. Clearances for F visas are valid for up to 4 years unless the student changes academic positions. H, J, and L clearances are valid for up to 2 years unless the visa holder’s activity in the United States changes.20

In 2002, a new antiterrorist screening process called Visas Condor was added for nationals of US-designated state sponsors of terrorism.21 That

|

17 |

The Visa Mantis program was established in 1998 and applies to all nonimmigrant visa categories, including student (F), exchange-visitor (J), temporary-worker (H), intracompany-transferee (L), business (B-1), and tourist (B-2) applicants. |

|

18 |

See http://travel.state.gov/visa/testimony1.html for an overview of the Visas Mantis programs and implementation of Condor. |

|

19 |

See Department of State cable, 04 State 153587, No. 22: Revision to Visas Mantis Clearance Procedure, http://travel.state.gov/visa/state153587.html. |

|

20 |

“Extension of validity for science-related interagency visa clearances.” Media Note 2005/ 182. US Department of State, February 11, 2005, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2005/42212.htm; “Overview of state-sponsored terrorism: patterns of global terrorism—2000.” US Department of State, April 30, 2001. http://www.state.gov/s/ct/rls/pgtrpt/2000/2441.htm. |

|

21 |

Countries designated section 306 in 2005: Iran, Syria, Libya, Cuba, North Korea, and Sudan. See “Special visa processing procedures–travelers from state sponsors of terrorism.” http://travel.state.gov/visa/temp/info/info_1300.html. |

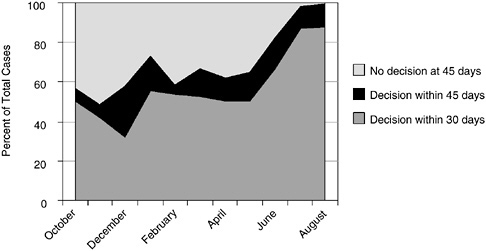

FIGURE 2-5 Visas Mantis Security Advisory Opinion (SAO) Workload, FY 2004

SOURCE: Data presented to committee on October 12, 2004, by Janice Jacobs, deputy assistant secretary of visa affairs, US Department of State.

addition initially overloaded the SAO interagency process and slowed Mantis clearances, drawing criticism and calls for improvement.22 The problem of extended waiting times for clearance of nonimmigrant visas flagged by Mantis has for the most part been addressed successfully. 23 In the last year, the proportion of Visas Mantis visitors cleared within 30 days has risen substantially (see Figure 2-5). In October 2003, over 40 percent took 45 days or more to clear; today, virtually none take that long, and fewer than 15 percent take more than 30 days.

OTHER IMMIGRATION POLICIES AND CONDITIONS

Changes in visa policies are only one factor that can affect the mobility of graduate students and postdoctoral scholars. Other immigration policies and conditions related to S&E flows are reciprocity agreements and deemed-exports agreements.

Reciprocity Agreements

A factor that may weigh heavily on those considering US graduate schools and postdoctoral research are the immigration reciprocity agreements between countries. Visa policy in one country that limits visitor entry is matched by the reciprocating country, thus affecting flow in both directions. Reciprocity agreements differ by country and for each class of visa and may include application fees, restrictions on the number of times a person may enter a country on a visa, or the duration of visa validity.24 For example, a 6-month validity period for F-1 and J-1 visa classes for Chinese citizens means that each time visa holders leave the United States, to return they must reapply for a visa. The 12-month validity period for F-class visas for Russian students can also be problematic.25 It is promising that China and the United States have agreed to reciprocally extend the visa validity for tourist and business travelers to 12 months and multiple entries.26

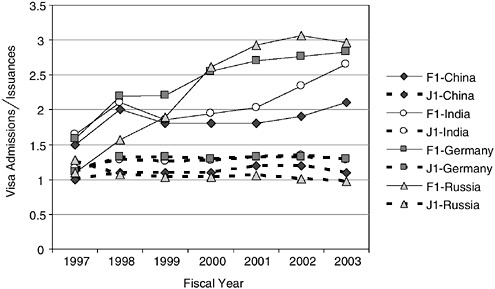

An analysis of the visa issuance and admissions data from countries with limited-entry visas for students indicates that J-visa holders, who tend to have multiyear multiple-entry visas, take fewer trips per year out of the United States than do F-visa holders (see Figure 2-6). That may be related to Visas Mantis screening. Most S&E graduate students and postdoctoral scholars who wish to re-enter the United States, even those with valid multiple-entry multiyear visas, must be recleared through Visas Mantis procedures—a process that can take over 30 days.

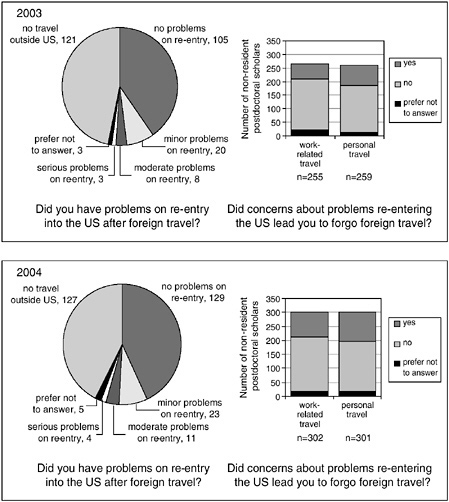

Many graduate students and postdoctoral scholars opt not to travel to international conferences or to visit home to see family, to avoid lengthy disruptions in study or research. A 2004 survey of nonresident postdoctoral scholars working in the United States indicates that about 20 percent of the respondents had curtailed work-related and personal travel in 2003 and 2004 because of concerns that they would have problems re-entering the United States. Of scholars that did travel outside the United States, over 20 percent experienced some problems and 2 percent experienced serious problems on re-entry in both 2003 and 2004 (see Figure 2-7).

|

24 |

See the reciprocity tables listed at http://travel.state.gov/visa/reciprocity/index.htm. |

|

25 |

It should be noted that students are legally in the United States for the duration of their studies (certified by SEVIS), but visa policies may prevent them from returning to complete their studies after travel abroad. |

|

26 |

Office of the Spokesman. 2005. “US extends visa validity for Chinese tourist and business travelers.” Media Note 2005/56, US Department of State (January 12), http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2005/40818.htm. |

FIGURE 2-6 Student and exchange-visitor trips per year, 1997-2003.

SOURCE: Data on visa issuances from US Department of State. Data on visa admissions are collected at ports of entry and are from Immigration and Customs Enforcement division, Department of Homeland Security. Note that DHS includes mainland China and Taiwan in its admissions reports for China. Department of State issuance numbers for China and Taiwan have been combined for comparability.

NOTES: Student (F) visas are issued for student-college/university and student-secondary (high-school only). Exchange visitor (J) visas are issued for private sector (foreign physician, au pair, camp counselor, summer work/travel, and trainee) and government program (student-college/university, student-secondary, professor, research scholar, short-term scholar, specialist, teacher, government visitor, and international visitor).

Reciprocity schedules dictate validity period of visa and number of times it may be used to enter United States. As of December 2004, reciprocity schedules were as follows: China: F1 and J1 6 months, two uses; India and Germany: F1and J1 60 months, multiple uses; Russia: F1 12 months, multiple uses; J1 36 months, multiple uses.

Deemed Exports

Export control laws have been a mechanism to control the transfer of goods having military applications through the International Traffic in Arms Regulations and have also become a means to limit the export of goods or technologies having commercial value through Export Adminis-

FIGURE 2-7 Re-entry issues for nonresident postdoctoral scholars.

SOURCE: Data are from a November 2004 survey of postdoctoral scholars at the National Institutes of Health carried out by Sigma Xi. Postdoctoral scholars in the United States on temporary visas were asked about their travel in 2003 and 2004. For the 2003 charts: Of 305 scholars who responded, 262 scholars were residing in the United States in 2003, 34 were not, and nine preferred not to answer. 260 of the residing scholars indicated whether they had traveled abroad in 2003:121 had not traveled outside the United States, 136 had, and 3 or fewer preferred not to answer. 135 out of the 136 scholars who had traveled outside the United States indicated whether they had had any problems re-entering the United States. For the 2004 charts: 301 of the responding scholars resided in the United States in 2004 and indicated whether they had traveled abroad in 2004. 127 had not traveled outside the United States, 169 had, and five preferred not to answer. 168 out of the 169 scholars who had traveled outside the United States indicated whether they had had problems re-entering the United States.

tration Regulations.27 Most significant for the international-student and of hardware, commodities, and data—a “deemed export” can occur by the scholar community is the determination that—in addition to the transport transfer of information to a foreign national studying at a US institution, even one who has obtained SAO clearance.

After 9-11, the US government considered whether there were sensitive fields, including fields that have a direct application to the development and use of weapons of mass destruction, to which international students should not be admitted.28 An analysis of international doctorate recipients showed that of the degrees awarded in 1990-1999, fewer than 11 percent were in sensitive fields, and most of these were in engineering. Students from countries that are now called state sponsors of terrorism constitute 2.0 percent of all PhDs awarded in 1990-1999. Some 79 percent of those students earned degrees in engineering, agriculture, or biological sciences.29 Universities have reported a substantial increase in situations in which a federal sponsor of research includes award language that restricts the dissemination of research results or the participation of foreign nationals without prior approval on specified research projects.30 Furthermore, restrictions on travel and study in embargoed countries can impede collaboration and cultural exchange for US students whose dissertation research involves international travel.

The ability to interact freely with and educate international students is preserved by the exemptions granted to universities for fundamental research and educational purposes; however, how these policies are interpreted can affect the ability to interact with students, postdoctoral scholars, and colleagues from other countries. The situation is causing immense frustration and is a subject of current discussion.31

|

27 |

Export of military hardware and technical data is controlled by the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR, see http://pmdtc.org/reference.htm), dating back to 1954; the export of commodities of commercial interest (and the technical data related to their design, manufacture, and use) is controlled by the Export Administration Regulations (EAR, see http://www.access.gpo.gov/bis/ear/ear_data.html), from 1979. |

|

28 |

Stephen Burd. 2002. “Bush may bar foreign students from ‘sensitive courses’.” The Chronicle of Higher Education (April 26) A26. |

|

29 |

Paula E. Stephan, Grant C. Black, James D. Adams, and Sharon G. Levin. 2002. “Survey of foreign recipients of US PhDs.” Science 295(5563): 2211-12. |

|

30 |

Julie T. Norris, “Restrictions on research awards. Troublesome clauses: A report of the AAU/COGR Task Force”. This report was requested of the American Association of Universities and Council on Governmental Relations (COGR) by the Office of Science and Technology Policy. The report is based on surveys conducted during Spring and Summer 2003. |

|

31 |

An AAU task force on export controls was established in late 2004. The Bureau of Industry and Security of the Department of Commerce posted an advance notice of proposed rule-making on the “Revision and Clarification of Deemed Export Related Regulatory Requirements” in the Federal Register on March 28, 2005. The public may submit comments, identified by RIN 0694-AD29, at the Federal eRulemaking Portal at http://www.regulations.gov. |

Section 214(b)

A serious barrier to visits by foreign graduate students is Section 214(b) of the INA, by which an applicant for a student or exchange visa must provide convincing evidence that he or she plans to return to the home country, including proof of a permanent domicile in that country (see Box 2-1). Legitimate applicants may find it hard to prove that they have no intention to immigrate, especially if they have relatives in the United States. In addition, both students and immigration officials are well aware that an F or J visa often provides entrée to permanent-resident status (see Chapter 1 for discussion of stay rates and conversion to permanent residence). It is not surprising that application and enforcement of the 214b requirement can depend on pending immigration legislation or economic conditions.32

RECENT EVENTS

At the time of this writing, US visa and immigration policies are in flux. The administration has responded to academic and industry leaders and added staff for visa processing and clearances.33 DOS has worked to expedite processing of F and J visas at consular posts and embassies.34 A survey of wait times posted on the DOS Web site indicates that student-visa applicants have a much shorter wait time than other nonimmigrant-visa applicants.35 DOS has also worked to reduce the time in which an SAO is issued and has extended the SAO validity period.36 DHS has implemented SEVIS and has just rolled out US-VISIT, another program that may help to provide consular officials independent verification of applicant identity. Universities have increased their efforts to facilitate the immigration and enrollment of graduate students by setting earlier application deadlines, sending earlier notification, offering counseling, and making better use of communication technologies.37

|

32 |

G. Chelleraj, K.E. Maskus, and A. Mattoo. 2004. The Contributions of Skilled Immigration and International Graduate Students to U.S. Innovation (Working Paper Number 04-10). Boulder, CO: Center for Economic Analysis, University of Colorado, p. 18 and Table 1. |

|

33 |

“Sanity on visas for students.” New York Times, February 16, 2005. |

|

34 |

US Department of State cable, 04 State 154060, “Student and exchange visitor processing reminder.” http://travel.state.gov/visa/student_exchange_reminder.html. |

|

35 |

|

|

36 |

Stephen A. Edson. 2005. “Testimony on tracking international students in higher education.” Before the Subcommittee on 21st Century Competitiveness and Select Education Committee on Education and the Workforce (March 17). http://travel.state.gov/law/legal/testimony/testimony_2193.html. |

|

37 |

Heath Brown. 2004. Council of Graduate Schools Finds Decline in New International Graduate Student Enrollment for the Third Consecutive Year. Council of Graduate Schools, Washington, DC (November 4). |

It is difficult to describe the effect of recent changes by field of study, because visa issuances are not categorized in this way. Visa admissions data have such classification, but there can be multiple entries per visa, so it is not an effective measurement tool. Data collected through SEVIS could be very helpful to researchers interested in international student flows, but they too are limited because the data begin in 2003, do not differentiate graduate students from postdoctoral scholars, and do not identify postdoctoral scholars who travel to the United States on H-1b or other nonimmigrant visas.

Little attention has been paid to the plight of graduate students and postdoctoral scholars who wish to attend a scientific meeting in the United States or who are invited to the United States for short-term research collaboration (weeks to a few months) that does not require registration for a university or industrial program. Such scholars do not receive stipends from US sources but may receive honoraria or reimbursement of expenses. Most institutions have been advised by DHS to tell such junior scholars to apply for a B-1 visa, just as for advanced scholars who are invited to institutions and meetings to lecture. However, the B-1 visa class definition (see Box 2-1) appears to exclude such use. The discrepancy is causing substantial confusion for university officials and international students and scholars. In addition, B-1 applicants, particularly students and postdoctoral scholars, are subject to the 214b requirement and can have difficulties in proving they do not intend to immigrate, even though their stays will be short and not US-funded, and they also must plan far in advance of meetings to allow time for the security review process.

CONCLUSION

The United States has long benefited from relatively open visa and immigration policies for international S&E students and researchers. Individuals and institutions that directly rely on or benefit from the presence of international graduate students and postdoctoral scholars, especially the university community, have been concerned that changes in visa and immigration policies after 9-11 jeopardized the flow of international scientists and engineers. In addition, international political views affect students’ and scholars’ willingness to come to study in the United States.38 That the

consequences were not as great as anticipated can probably be attributed to efforts by the US government to make the nonimmigrant-visa application process work effectively and to measures taken by universities to make the graduate application process responsive to international-student needs.

Student flows respond quickly to alterations in immigration policies. However, the inflow of talented graduate students and postdoctoral scholars is unlikely to be severely affected as long as the world sees the United States as the most desirable destination for S&E education, training, and technology-based employment. If that perception shifts, and if international students find equally attractive educational and professional opportunities in other countries, including their own, the difficulty of visiting the United States could gain decisive importance. Chapter 3 discusses the possibility that such a long-term shift already is occurring.

|

|

Origin (Working Paper). Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education.) and postdoctoral scholars (see: Jurgen Enders and Alexis-Michel Mugabushaka. 2004. Wissenshaft und Karriere: Ehrfahrungen und Werdegange ehemahleiger Stipendiaten der DFG. Bonn: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). |