Executive Summary

TODAY’S FRAMEWORK IN PERSPECTIVE

Today U.S. naval forces are dependent on space systems in many ways—for communications; command and control; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); navigation; and meteorology and oceanography (METOC)—and they will be even more so in the future. In particular, the Department of the Navy has witnessed significant changes in both the national security environment1 and the Department of Defense (DOD) posture toward the support and development of space technologies. For example, the homeland defense mission recently established by the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) tasks the Navy (in concert with the U.S. Northern Command, the Coast Guard, and other federal agencies) to develop new systems and procedures to protect the maritime approaches to the United States.2 While the Navy’s specific roles and responsibilities in support of this mission remain undefined, warranting clarification, they will likely entail new and greater reliance on space—for example, to supply near-continuous, open-ocean surveillance of all surface craft.

To refocus Department of the Navy attention for purposes of these new missions, the Naval Services have recently promulgated a series of capstone vision documents. These include the Department of the Navy capstone vision, Naval Power 21;3 its succeeding operational extension, the Naval Operating Con-

cept for Joint Operations;4 and the preceding Navy and Marine Corps vision documents, Sea Power 215 and Marine Corps Strategy 21,6 respectively. In general, these documents show a progression of visions that has integrated most of the Service-specific concepts into a broader structure founded on the four concepts presented in Sea Power 21—Sea Strike, Sea Shield, Sea Basing, and FORCEnet.

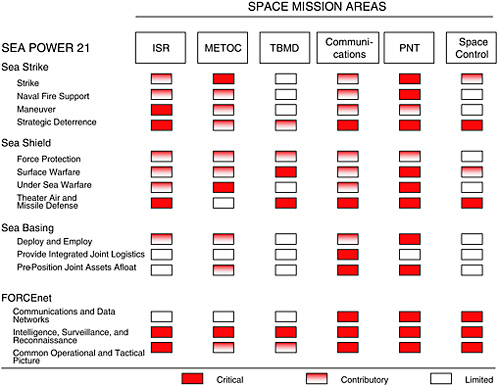

Using Sea Power 21 as an operational framework and taking into account new missions, such as the provision of a joint task force afloat headquarters or ocean surveillance for homeland security, the Committee on the Navy’s Needs in Space for Providing Future Capabilities estimated the extent of the dependency of the Naval Services on space systems—specifically on capabilities provided by National Security Space (NSS) mission areas; the committee’s estimate is summarized in Figure ES.1. An assessment of the status of current and proposed major DOD space systems, given in Table ES.1, indicates the Navy’s reliance on space system development and operations led by other agencies. While the capabilities of many of today’s space systems (in navigation, ISR, communications, and space control) originated in numerous efforts previously supported by the Navy, today most space systems supporting naval operations are operated by other government agencies or by commercial firms.

The continual replacement and the upgrading of most of these major space systems (for which the satellites typically have a design lifetime of less than 15 years) are being planned, and the deployment of these satellites is anticipated to cost tens of billions of dollars over the next 15 years. To help the DOD leverage the resulting opportunities, as well as ensuring its future needs will be met, William Cohen (then Secretary of Defense), in 2000, commissioned a space review panel to investigate NSS management and organization.7 Shortly after becoming Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, who had initially chaired the DOD Space Commission, enacted many of the report’s recommendations. This action, promulgated as Directive 5101.2,8 establishes a DOD Executive Agent for Space, a responsibility currently assigned to the Under Secretary of the Air Force,

|

4 |

ADM Vern Clark, USN, Chief of Naval Operations; and Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2003. Naval Operating Concept for Joint Operations, Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., September 22. |

|

5 |

ADM Vern Clark, USN, Chief of Naval Operations. 2002. “Sea Power 21,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 128, No. 10, pp. 32-41. |

|

6 |

Gen James L. Jones, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 1999. Marine Corps Strategy 21, Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., July. |

|

7 |

Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization. 2001. Report of the Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization, Washington, D.C., January 11. |

|

8 |

The full text of DOD Directive 5101.2, “DOD Executive Agent for Space,” is provided in Appendix B. |

FIGURE ES.1 Dependency of Sea Power 21 as an operational framework on capabilities provided by National Security Space mission areas. (A list of acronyms is provided in Appendix G.) NOTE: A “critical” dependency reflects a space mission area that is considered absolutely necessary for the accomplishment of the particular Sea Power 21 capability. For example, without access to space-based ISR information, the Navy could not generate the common operational and tactical picture needed to support FORCEnet; thus, these two areas are denoted critical. A “contributory” dependency reflects a space mission area that will provide support for accomplishing the particular Sea Power 21 capability.

and directs the Services to assist the DOD Executive Agent for Space in developing capabilities and priorities to meet their needs.9

The DOD Executive Agent for Space is specifically tasked to collect input from the relevant Service and intelligence communities in order to coordinate,

TABLE ES.1 Status of Current, Planned, and Proposed Department of Defense Space Systems Programs, Including General System Limitations and Risk

|

Space-Based Capability |

Current Programs |

Available? |

Oversight Agency |

|

Imagery (infrared, visible, radar) |

NRO systems, FIA, SBR commercial imagery |

Yes |

DOD Executive Agent for Space, NRO, NGA |

|

Electronic intelligence (ELINT) |

NRO systems |

Yes |

DOD Executive Agent for Space/NRO |

|

Navigation |

GPS |

Yes |

Air Force |

|

Timing |

GPS |

Yes |

Air Force/Navy |

|

Meteorology and oceanography |

GOES, POES, NPOESS |

Yes |

NOAA |

|

Ground moving target indication |

SBR |

No |

Air Force |

|

Airborne moving target indication |

None |

No |

None designated |

|

Boost-phase missile defense |

SBIRS-H |

No |

MDA |

|

Midcourse missile defense |

SBIRS-L |

No |

MDA |

|

Space-based IP networks (GIG) |

TCA |

No |

DOD Executive Agent for Space |

|

Satellite communications |

MUOS, MILSTAR, AEHF, commercial |

Yes |

Air Force and Navy |

|

NOTE: A list of acronyms is provided in Appendix G. |

|||

prioritize, program, acquire, and operate all National Security Space systems. Not included among the NSS systems are the nation’s meteorology and oceanography systems, which are currently mandated to fall under oversight by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as executive agent.

In light of these organizational changes, the Navy should revisit its approach to supporting and leveraging national space capabilities. Only two current space systems, the Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) and the Geodetic Satellite (Geosat), are currently under Navy control. Some in the Navy have argued that a passive stance can be taken—that it is the Air Force’s responsibility to supply all space-related military needs and that the Navy should act only as a “ruthless customer” of NSS capabilities. In this view, useful naval adaptations, once systems are on-orbit and in operation, could be made through the Navy’s Technical Exploitation of National Capabilities Program (Navy-TENCAP), as has been done in the past. Others in the Navy indicated to the committee their concern that

|

General Limitations |

Status/Risk |

|

Satellite revisit time |

FIA and SBR in development, SAR versus GMTI trade-offs for SBR |

|

Encryption, geolocation accuracy |

Gap-filler satellite may fill need |

|

Vulnerability to countermeasures |

Enhanced jamming protection programmed |

|

Few |

Ongoing clock development |

|

Passive sensors only, resolution and revisit times, international partnerships |

Cost, feasibility of active sensors |

|

Revisit time, field of view, data rates |

R&D issues, cost, trade-offs between SAR and GMTI, ubiquitous coverage |

|

Stressing technology, data rates |

Ubiquitous coverage, use of space sensor for weapon guidance |

|

Stressing technology |

Cost, technical risk, system under development |

|

Stressing technology |

Cost, technical risk, no current program |

|

Wideband laser links |

Development risk, cost, system under development |

|

Data assurance, link availability |

Bandwidth demands growing rapidly |

the Air Force may not take sufficient account of naval needs as system design trade-offs are made to meet cost and schedule constraints or as system priorities are modified.

The committee concluded that, in the foreseeable future, a change in the executive agent roles for the Air Force and NOAA is unlikely. Thus, a more active role should be assumed by the Navy and Marine Corps, through multiple interfaces with the executive agents, to ensure that naval space support needs are met and to take advantage of opportunities offered by the large funding outlays now being made.

In 2002 the Panel to Review Naval Space recommended several steps toward such an active role.10 The present committee reviewed progress on these recom-

mended directions, concluding that more can and should be done to ensure that the naval forces’ needs for support from space are met. The committee’s major recommendations, presented below, are parallel to those of the 2002 review panel study, and are focused on the following areas:

-

Establishing a new Department of the Navy space policy,

-

Determining and articulating Navy space needs,

-

Increasing participation in National Security Space activities,

-

Reinvigorating support of Navy space science and technology,

-

Enhancing experimentation in the development of space systems,

-

Strengthening the naval space cadre, and

-

Taking technical and programmatic steps to leverage National Security Space mission areas.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MEETING NAVAL FORCE SPACE NEEDS

Establish a New Department of the Navy Space Policy

The Department of the Navy should first move to fulfill the responsibilities assigned to it by the DOD in Directive 5101.2, that is, to assist the DOD Executive Agent for Space in developing maritime space capabilities. The committee’s perception is that not much has been done by the Navy Department toward compliance with this directive. For example, to date, no documents or policy statements have been provided to the DOD Executive Agent for Space detailing how the Department of the Navy will support its assigned responsibilities.11 In part, this may be because responsibility for this response was delegated to the Under Secretary of the Navy, and that position was vacant before the directive was promulgated.12 Taking into consideration the lack of input from the Under Secretary of the Navy, the committee was nonetheless concerned that the Department of the Navy had not yet begun to fulfill its responsibility under DOD Directive 5101.2 by updating the Department of the Navy space policy—last done in 1993.13

Recommendation 1. The Secretary of the Navy should task the Chief of Naval Operations and the Commandant of the Marine Corps to formulate and take steps to establish a new Department of the Navy space policy.

This space policy should provide a framework for Department of the Navy participation in the planning, programming, and acquisition activities of the Department of Defense Executive Agent for Space, and include definition of the Navy Department’s relationship to National Security Space activities. A primary objective of the Department of the Navy space policy should be to focus attention on space mission areas critical to the successful implementation of Naval Power 21 as well as on other national maritime responsibilities such as homeland defense.

Determine and Articulate Navy Space Needs

Recently the Navy has begun to alter its process for generating space-related requirements to place a greater emphasis on operational inputs and greater reliance on joint Service interoperability and integration of needs.14 However, in the information available to it, the committee could not identify a rigorous, end-to-end, well-connected process within the Navy for determining, prioritizing, and articulating naval space needs. The contributions of space support to existing and anticipated naval missions should be analyzed operationally for costs and benefits, and requirements for such support should be formulated and strongly articulated in a timely fashion in order to have an impact at the points in the process at which system-design trade-offs are made. In general, the earlier a Navy need can be identified and its usefulness clearly articulated, the easier it becomes to support that need throughout the processes of requirements generation, prioritization, and acquisition.

The lack of an up-front, crosscutting analysis of naval force space needs appears to have led to a lack of clear requirements for the space assets and capabilities that are necessary to accomplish Sea Power 21. For example, there was insufficient operational analysis linking communications connectivity needs with ongoing ISR capability developments to ensure that naval vessels will be able to access the high-volume data sets envisioned in the near future—a capabil-

ity particularly needed to enable sea basing of a joint task force headquarters as envisioned in Sea Power 21.15 Without clear requirements supported by sound analysis going forward, the Navy lacks the backing to articulate and ensure adherence to its requirements as programs progress through the Navy, joint Service, and DOD acquisition process. In addition, the lack of articulated needs appears to have kept space capability gaps from being identified and forwarded to the experimentation and science and technology (S&T) communities for further examination.

Recommendation 2. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) should task the appropriate organizations—including the Commander, Fleet Forces Command; the Deputy CNO for Warfare Requirements and Programs; and the Deputy CNO for Resources, Requirements, and Assessments—to strengthen the Navy’s requirements process for identifying space capability needs.

Specifically, the Navy should increase its support of operations research, systems analysis, and systems engineering (both internally and externally performed), since the Navy appears to lack sufficient resources in these areas. Operational analysis is central to the process of integrating needs across Sea Power 21 capability areas and National Security Space mission areas. The results of this analysis should be articulated for purposes of prioritization to the appropriate organizations—those with responsibility for requirements, acquisition, science and technology, and experimentation. In this process, these organizations should use common simulation, modeling, and analysis tools that are also compatible with the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS).16

Increase Participation in National Security Space Activities

In the absence of sustained, active participation by the Department of the Navy in staffing, management attention to, and funding of NSS programs, it is

|

15 |

As discussed in the section entitled “Space-Based Communications” in Chapter 4 of this report, Navy plans are to increase command ship (LCC) bandwidth capacity to approximately 10.5 Mb/s by FY07, in stark contrast to joint task force bandwidth usage of up to 750 Mb/s during Operation Iraqi Freedom. |

|

16 |

The JCIDS process is based on top-level strategic direction, provided by the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC), to guide development of new capabilities. Capability recommendations and requirements are developed by the Services and evaluated by the JROC in consideration of how to optimize joint force capabilities and maximize interoperability. All major new programs are expected to participate in the JCIDS process. |

unrealistic to expect NSS programs to consistently take account of and support technical and operational requirements that are unique to naval needs. The committee’s perception, in particular, was that the Department of the Navy maintains an uncertain posture in relation to most NSS programs.

In contrast, the long-standing Navy participation in the activities of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) seems effective and could serve as a model for its interactions within the NSS realm. Also, Navy-TENCAP activities seem to be well supported by the Navy and, while limited by law to the exploitation of existing (in-orbit) space systems, Navy-TENCAP activities have often led to new naval capabilities.

A current example of problems arising from the Navy’s lack of participation in NSS activities is the difficulty that the Navy has been having in establishing its maritime requirements as part of the Air Force Space Based Radar (SBR) program. SBR plans are to field a single system capable of collecting both ground moving target indication (GMTI) and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery; the committee believes that this system has significant potential to meet a variety of naval needs, including open-ocean surveillance. The Navy does not appear to have established the organization, technical depth, analytic ability, and funding to significantly influence SBR. As a result, the Navy appears to be struggling to keep up, resorting to last-minute nonconcurrence in decisions of the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) when programs do not properly reflect naval requirements. In addition, GMTI imagery must contend with Doppler-induced background clutter that has significantly different character for land use and for marine use, signifying a potential area in which Air Force land use priorities could impact Navy needs. Thus, a lack of early Navy support for naval interests in this area may result in not having naval space needs met, or in having to fund alternative solutions at a later date and greater expense.

Recommendation 3. The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the naval forces are adequately staffed and supported to influence National Security Space programs that have the potential to meet important naval space needs.

The Navy should engage early, with sufficient technical and management depth to influence the requirements generation, resourcing, and acquisition of new space systems being developed by the Air Force, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Reconnaissance Office, and other (commercial and government) partners. In addition, the Navy’s engagement should include tasking appropriate naval commands to provide inputs for (see Chapter 3, “Roles and Responsibilities”) and participate directly in (see Table ES.2 in the final subsection of this Executive Summary) NSS activities.

Reinvigorate Support of Navy Space Science and Technology

The DOD Space Commission report,17 as well as the related DOD directives issued subsequently,18 emphasized the vital importance of U.S. leadership in space. One way that this leadership can be assessed is through the technological innovation and research and development (R&D) aimed at generating satellites that have the greatest long-term benefits.19 However, this committee’s perception is that the Navy, which at one time held a leadership position in national space science and technology, has allowed its support of space S&T to wither to such an extent that it is no longer adequate to support Navy needs for broad expertise in space issues or the technical expertise in space-based ISR, communications, and METOC systems essential to Sea Power 21.20 The Navy’s Mobile User Objective System program is an exception: enduring maritime needs for mobile, narrowband satellite communications have justified continual Navy support of ultrahigh frequency communications and signal propagation research. While necessary to support MUOS, this R&D effort does not generate broad technical knowledge across other NSS mission areas and may result in the naval requirements community’s overlooking opportunities to increase Navy capabilities using space systems.

The committee has a particular concern for the Navy’s in-house base of space technology expertise: the Naval Research Laboratory’s (NRL’s) Naval Center for Space Technology (NCST). Beyond the “core” support provided from NRL, there has been little recent support for NCST by the Office of Naval Research (ONR); rather, funding from non-naval organizations has allowed NCST to maintain a critical mass of personnel, facilities, and technical credibility to support the development of a number of capabilities useful to the Navy.21 NCST staff described to the committee several proposals to develop novel maritime space capabilities (for direct user tasking, emerging wideband communications to disadvantaged naval platforms, and improved radio-frequency emitter tracking)

|

17 |

Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization. 2001. Report of the Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization, Washington, D.C., January 11. |

|

18 |

DOD Directive 5101.2, “DOD Executive Agent for Space,” with an enclosure listing other relevant directives, is presented in Appendix B of this report. |

|

19 |

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Satellite Commission. 2002. Preserving America’s Strength in Satellite Technology, CSIS, Washington, D.C., April. |

|

20 |

For example, Office of Naval Research (ONR) space-related funding in environmental effects and spacecraft technology research was approximately $14 million in FY03—less than 1 percent of total ONR FY03 funding, according to RADM Jay Cohen, USN, Chief of Naval Research, presentation to the committee, October 29, 2003. |

|

21 |

One recent example is NCST’s construction of the WindSat sensor, used to measure sea-surface wind speed and direction, and the integration of the sensor onboard the recently launched Coriolis satellite. |

that have since received support from the DOD through the TacSat program.22 The committee finds that the Navy does not appear to be interacting with NCST and taking advantage of NCST’s potential to develop maritime space mission concepts, to demonstrate on-orbit space-based capabilities that support maritime operations, or to transition technology to industrial or government partners for system production.

Several emerging technologies, such as space-based radar and hyperspectral imaging (for which NCST has constructed the prototype Naval EarthMap Observer (NEMO) sensor payload), can provide capabilities to support Sea Power 21. This can happen, however, only if the naval forces provide the leadership and support necessary to develop the technical understanding of how systems can be designed and integrated into new platforms and to provide the knowledge to articulate system requirements to the broader NSS community.

Recommendation 4. The Chief of Naval Research (CNR) should maintain a critical level of space mission area funding aimed at supporting current maritime needs as well as at providing broad support to base-level technologies with the potential to support National Security Space programs, such as the Transformational Communications Architecture and Space Based Radar programs.

Specifically, the CNR should continue (or preferably increase) current levels of basic research (6.1) and applied research (6.2) funds in support of space technologies and systems. In addition, the CNR should consistently allocate advanced research and development (6.3) funds to enable regular Navy space sensor development and on-orbit testing. Given recent Navy space sensor program allocations as a benchmark, the committee envisions that a level on the order of $40 million annually of 6.3 support would be sufficient to ensure regular development of new Navy space systems. Specific space mission areas recommended are as follows:

-

Communications. Robust on-orbit capabilities supporting naval communications needs such as connecting historically disadvantaged users to future sea-based command centers via the Global Information Grid and creating the low-latency weapons control connections necessary for effective missile defense;

-

Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; and meteorology and oceanography. Improved on-orbit capabilities, ranging from modified sensors to new capabilities including hyperspectral imaging, to support emerging needs arising from Sea Power 21; and

-

Data fusion. Using space-derived information and systems in scaling and optimizing global information capabilities in support of Sea Power 21 operations.

|

22 |

Additional information on TacSat is provided in Chapter 3, in the section entitled “Navy Space Support.” |

Additional space mission area recommendations are provided in Table ES.2 in the final subsection of this Executive Summary.

Enhance Experimentation in the Development of Space Systems

The NSS community’s ongoing transformation of space systems will continue to offer new opportunities to improve naval capabilities. One ready means for leveraging these opportunities is through experimentation. Typically, experimentation is used not only to test new technologies that may prove useful to the operational forces, but it is also used to provide a forum in which operators test developing technologies and provide feedback on how the technologies, or underlying concepts of operations, can be modified to improve capabilities. Additionally, experimentation often identifies or highlights capability gaps in need of further R&D. A key to the experimentation process, however, is the clear identification and prioritization of operational needs; only when these needs are established can appropriate, focused experimentation efforts be constructed.23

Current Navy experimentation programs, however, do not appear to be derived from articulated operational needs and thus may not effectively support new capabilities. In part this is because the Navy has not conducted rigorous analyses of the missions and capabilities needed to accomplish the goals of Sea Power 21 (see Recommendation 2). The Navy has acknowledged the need to tie operational needs more effectively into experimentation efforts, which has resulted in the establishment of Sea Trial.24 Sea Trial is described as the “process to go from strategy based concepts through experimentation to proposed [mission capability plans] and the [naval capability plan], to changes in doctrine, organization, training, material, leadership development, personnel, and facilities (DOTMLPF).”25 While led by the Commander, Fleet Forces Command (CFFC), the Sea Trial effort is managed by the Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC), and for issues related to space and network-centric operations Sea Trial is also guided by the Naval Network Warfare Command (NETWARCOM).26 In addition, Sea Trial is coordinated with the Joint Forces Command experimentation process, which is exploring the best uses of space-based intelligence capabilities for all of the Services.

The Navy’s current experimentation programs involving space have been largely opportunistic, taking advantage of new technologies predominantly developed outside the Navy, to make incremental improvements in fleet performance. In addition, the Navy has focused heavily on advanced antenna technologies usable from large mobile platforms. Navy-TENCAP is a commendable example of experimentation with fielded NSS programs (ISR in particular), enabling those systems to provide critical intelligence to the tactical users. Today, a benchmark for Navy tactical exploitation of space is the Navy’s use of the national electronic intelligence (ELINT) systems.

Current Navy space system experimentation does not appear to have come from a strategic and tactical planning process that identified and prioritized new capabilities necessary to meet the goals of Sea Power 21 successfully. As a result, there appears to have been limited success in transitioning successful space experimentation results into programs of record. To improve this situation, the committee believes that a closer integration among CFFC, NWDC, and NETWARCOM is needed.

Recommendation 5. As part of the Sea Trial experimentation process, the Commander, Fleet Forces Command, should formalize the roles between the Naval Network Warfare Command (NETWARCOM) and the Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC) pertaining to maritime and joint forces experimentation in space and space-related areas so as to fully exploit and complement the Joint Forces Command experimentation process and to explore the best uses of future space-based intelligence capabilities.

In particular, NETWARCOM and NWDC should carry out the following:

-

Coordinate with the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Requirements and Programs in order to generate experimentation initiatives aimed at addressing space capabilities requirements;

-

Perform analysis, modeling, and simulation in a simulation-based acquisition approach on potential new space capabilities before proceeding to testbeds and field experiments; and

-

Conduct experimentation aimed at supporting new or improved sensors and subsystems that can piggyback on available NSS satellites.

Strengthen the Naval Space Cadre

The current naval space cadre represents an excellent pool of uniformed Navy and Marine Corps officers and civilians, trained and experienced with existing space systems and with the use of these systems’ products in tactical applications. However, recent downturns in Navy-funded space projects and a shift in space mission area responsibilities to the DOD Executive Agent for Space (and thus to the Under Secretary of the Air Force) appear to be leading to a

downturn in the ability of the space cadre to retain its viability. Thus, the committee sees an expanded space cadre as the key to ensuring that naval space needs can be articulated, addressed, and satisfied. The Navy’s demonstrated leadership in the NRO, MUOS, and Navy-TENCAP has relied on having educated, trained, and motivated teams of personnel knowledgeable about space to help develop new space systems.

As discussed above, emerging NSS programs, for example, SBR, offer new opportunities for naval warfighting capabilities. However, without the Department of the Navy’s sustained involvement in all phases of these programs, it is unlikely that they will deliver the level of performance that the Navy will need in the future. The Naval Services recently moved to improve the development and organization of their respective space cadres. For example, the Navy established a position for a flag officer whose primary responsibility is to direct and oversee the future development of the Navy space cadre. As part of this effort, the Navy also created the first listing of space-rated billets and space-rated personnel (collectively defined as the Navy space cadre). As the Navy space cadre develops, it is anticipated that more and more space-rated billets will be filled by members of the space cadre (in 2003, only approximately 20 percent of the space billets were occupied by members of the space cadre).27 The recently established Marine Corps space cadre is still developing, and its influence in Marine Corps space planning and programming is being established.

The underpinning for a knowledgeable space cadre starts with advanced education, such as that provided through the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) Space Systems programs. These programs provide graduate education in space systems engineering and operations for officers of all the military services. A Joint Space Oversight Board, chaired by the DOD Executive Agent for Space, has been established to ensure consistency between efforts of the NPS and the Air Force Institute of Technology in space education. Navy leadership must remain actively engaged in this forum to ensure that both the quality and the scope of the NPS curricula remain responsive to maritime needs. The committee also noted that Marine Corps involvement with regard to the direction and content of the space systems curricula has increased, representing recognition of the growing relationship between space expertise and the needs of expeditionary warfare.

Relative to the trends of the previous decades, a disturbing decrease was noted in the recent Navy quotas and assignments to the NPS Space Systems programs.28 Given the opportunities, challenges, and responsibilities offered un-

TABLE ES.2 Recommendations for Department of the Navy Participation in and Support of the Six National Security Space Mission Areas

|

Space Mission Area |

Recommendation |

|

|

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance |

4.1 |

The Department of the Navy should develop and fund directed operational analysis and science and technology (S&T) programs focused on addressing the Navy’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance shortfalls independent of whether or not the affected programs are managed by the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense (DOD) Executive Agent for Space. The Department of the Navy should also work to transition the results of these efforts into planned and ongoing National Security Space programs. |

|

4.2 |

The Department of the Navy should continue its full support of National Reconnaissance Office intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) activities and seek to extend its involvement in ISR program planning, development, and execution across other agencies’ ISR efforts. |

|

|

4.3 |

The Department of the Navy should provide budget authority to augment National Security Space intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance programs to permit program and system additions that address needs unique to Navy strategies (such as maritime operation). |

|

|

4.4 |

The Department of the Navy should coordinate with other agencies to support the development of advanced sensing technologies not currently part of the program plans of the DOD Executive Agent for Space. One such program that the committee believes has significant potential to provide new naval capabilities is the Naval EarthMap Observer (NEMO) hyperspectral imaging satellite. |

|

|

Meteorology and Oceanography |

4.5 |

The Department of the Navy should remain involved in developing and operating Navy-unique satellite systems. Thus, the Department of the Navy should reassess its meteorology and oceanography (METOC) remote sensing priorities. It is the view of this committee that these assessments should focus on the following: • Ensuring strong support for the Geosat (Geodetic Satellite) Follow-on program, • Completion and launch of the Naval EarthMap Observer (NEMO) satellite, and • Completion and launch of the Geosynchronous Imaging Fourier Transform Spectrometer/Indian Ocean METOC Imager (GIFTS/IOMI) satellite. |

|

4.6 |

The Department of the Navy should pursue research and development of integrated active and passive microwave satellite sensors development programs with the National |

|

|

Space Mission Area |

Recommendation |

|

|

|

Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to enable all-weather meteorology and oceanography sensing, along with measurements of trafficability, fog and visibility, and sea-ice mapping. The Navy should also continue to explore other research demonstrations, including active satellite systems and higher-resolution systems for hyperspectral imaging and sounding, atmospheric refractivity characterization and prediction, ocean color and biological constituents monitoring, and denied-area shallow-water bathymetry. |

|

|

|

4.7 |

The Chief of Naval Research should modify Office of Naval Research technology transition rules to allow transition-oriented funds to support non-Navy (and non-DOD) meteorology and oceanography programs such as those fielded by NOAA and NASA. |

|

Theater and Ballistic Missile Defense |

4.8 |

The Navy should continue its aggressive support of the E-2C aircraft Radar Modernization program so that a fleetwide capability can be achieved as soon as feasible. |

|

4.9 |

The Department of the Navy should begin operational analysis of the cost, benefits, and requirements of a cruise and ballistic missile defense system based on a multimode missile and an airborne moving target indication (AMTI) space-based radar (SBR) system. The Department of the Navy should invest in a focused science and technology program to resolve the issues that currently render an AMTI SBR infeasible. |

|

|

Communications |

4.10 |

The Department of the Navy should increase its depth of understanding of Navy and integrated joint future communications needs. |

|

4.11 |

The Department of the Navy should fund and manage an expanded operational analysis program focused on supporting research and development in space-based communications. |

|

|

4.12 |

The Department of the Navy not only should support research and development programs, but also should support experimental programs aimed at supporting space-based communications. |

|

|

4.13 |

The Department of the Navy should direct research and development aimed at the problem of low-latency communications from space-based sensors to platforms, particularly with respect to the cueing of fast-moving targets from beyond-line-of-sight sensors and national systems. Such an activity should be done in conjunction with improvements to the Cooperative Engagement Capability as well as other missile defense efforts. |

|

|

Space Mission Area |

Recommendation |

|

|

|

4.14 |

The Department of the Navy should focus more science and technology efforts on consolidated antenna and terminal configurations necessary to enable near-100-percent-reliable shipboard communications. |

|

4.15 |

The Department of the Navy should support a naval space-based communications challenge and fund its science and technology (S&T) community to aggressively anticipate potential future space-based communications requirements. |

|

|

4.16 |

The Department of the Navy should continue its role as lead agency for narrowband communications. The Department of the Navy should direct the Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) program to direct special attention in FY05 to ensuring that MUOS will interface effectively as an edge system in the Transformational Communications Architecture, and to harden the system, as is feasible within cost and schedule constraints, against the evolving counterspace threat environment. |

|

|

4.17 |

The Department of the Navy should revise its strategy of relying largely on commercial and unprotected communications during conflict. The Navy should carefully review the nature of potential threats to unprotected communications, both ground-and space-based, and take these threats into account when specifying next-generation communications needs and requirements. The Navy should also determine its core warfighting communications capability needs and should specify robust protection for these minimum capabilities to ensure adequate communications capabilities in the event of a total loss of access to commercial systems. |

|

|

4.18 |

The Department of the Navy should increase its personnel assignments to support the Transformational Communications Architecture program. The Department of the Navy should allocate naval personnel so that on the order of 10 to 15 percent of the total military and support staffing of this major acquisition program is represented by the Naval Services. |

|

|

Position, Navigation, and Timing |

4.19 |

The Department of the Navy should retain close ties with the Global Positioning System (GPS) Joint Program Office during the development of upgraded GPS space and ground segments. The Department of the Navy should also ensure that specific applications of integrated GPS (precision weapons systems, for example) are coupled to spacecraft capabilities that affect the resistance of these systems to radio-frequency interference (jamming). The Department of the Navy should conduct trade-off studies to determine the most cost-effective approach and strategy in developing guidance systems that rely on a combination of GPS and inertial guidance capabilities. |

|

Space Mission Area |

Recommendation |

|

|

|

4.20 |

The Department of the Navy should initiate a GPS synchronization study similar to that being conducted by the Air Force to ensure that M-code (military-only) user equipment development is synchronized with space- and ground-segment M-code capabilities. |

|

4.21 |

The Department of the Navy should sustain support to continue research and development in the area of precision timing standards and time transfer techniques, especially for potential use in future GPS space systems. |

|

|

Space Control |

4.22 |

The Department of the Navy should explore potential sea-based space control concepts in coordination with the activities of the DOD Executive Agent for Space. |

der the new DOD Executive Agent for Space, reversing this downward enrollment trend will be important.

Recommendation 6. The Chief of Naval Operations should strengthen and expand the Navy space cadre as follows:

-

Continue formalizing the leadership of the Navy space cadre under the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Requirements and Programs;

-

Provide additional (new) billets to support National Security Space (NSS) research, development, and acquisition efforts;

-

Ensure opportunities for positions of responsibility in all NSS activities and space mission areas;

-

Review the function of fleet and operational staff billets and assign space codes to billets as appropriate; and

-

Reexamine the Navy’s support of and quotas for the Naval Postgraduate School space systems programs in light of expanded naval involvement in NSS activities.

Take Technical and Programmatic Steps to Leverage National Security Space Mission Areas

In addition to reassessing large-scale naval involvement in and support of space activities, the Department of the Navy will also need to improve its approach to leveraging the unique opportunities present in each of the NSS mission areas. Table ES.2 lists the committee’s technical and programmatic recommen-

dations resulting from the detailed discussion of Navy space support presented in Chapter 4, “Implementation: Navy Support to Space Mission Areas.” The recommendations listed in the table are aimed at encouraging the Department of the Navy to participate in and support each of these mission areas, taking advantage of the unique opportunities and challenges associated with each of these mission areas and advocating technical and programmatic means to ensure that these NSS areas support naval needs.