1

Introduction

“In the highly interconnected and readily traversed ‘global village’ of our time, one nation’s problem soon becomes every nation’s problem…”

—Microbial Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection, and Response, Institute of Medicine, March 2003

THE COMMITTEE’S STATEMENT OF TASK

Animal health is profoundly affected by the forces of globalization and trade, the threat of bioterrorism, the restructuring and consolidation of food and agriculture production into increasingly larger commercial units, and even by human incursions into wildlife habitats. A very large network of people, organizations, and operations undergird a framework of systems to protect animal health in the face of these forces; when changes occur that affect animal health, they also impact the framework. In recognition of the importance of the relationship of the animal health framework to changing conditions for animal health domestically and internationally, the National Academies and its Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources (BANR) have launched the first phase of a proposed, three-part initiative to review the state and quality of the framework and evaluate current opportunities and challenges to its effectiveness to preserve animal health (see Box 1-1).

The Committee’s Approach to Its Task

As the product of the first stage of the initiative, this report provides a general overview of the structure of the animal health framework; identifies opportunities and barriers to the prevention, detection, and diagnosis of animal diseases; and, recommends courses of action for first-line responders and other participants in the framework, including the potential to apply new scientific knowledge and tools to address disease threats. This

|

BOX 1-1 A comprehensive review of the U.S. system and approach for dealing with animal diseases will be conducted. This initiative will (1) review, summarize, and evaluate the state and quality of the current system and the potential for improved application of scientific knowledge and tools to address threats and response efforts; (2) identify key opportunities and barriers to successfully preventing and controlling animal diseases as they relate to responsibilities and actions of producers, regulators, policy makers, and animal health care providers; and (3) identify courses of action for first-line responders to integrate strengths of proven strategies with promising approaches to meet animal health and management challenges. The study will be conducted in three phases, which correlate to the three major components of the U.S. structure of defense against animal diseases outlined in previous Board on Agriculture and Natural Resource (BANR) reports. The first phase of study will focus on the nation’s framework for prevention, detection, and diagnosis of animal disease. The second phase will focus on the nation’s system of monitoring and surveillance, and the third phase will focus on mechanisms of response and recovery from an animal disease epidemic. A core group of committee members will be appointed to participate in all phases of the activity to ensure consistency among the different phases, supplemented with additional expertise as needed for each phase. In its examination, the committee will assess the adequacy of:

For the first phase of the study, the committee will examine challenges in prevention, detection, and diagnosis presented by at least two specific animal diseases such as rinderpest; foot-and-mouth disease; West Nile virus; avian influenza; Newcastle disease; spongiform encephalopathies (scrapie in sheep and goats, chronic wasting disease [CWD] in deer and elk, transmissible mink encephalopathy [TME], and feline spongiform encephalopathy), and Q fever. These diseases represent a sample of diseases categories that have potential economic impact, human and/or animal health impact, or are foreign to the United States. They represent diseases, some which are zoonotic, that could affect each of the major agricultural species. The study will not address diseases that have been recently studied by BANR, such as brucellosis, Johne’s disease, or bovine tuberculosis. |

|

For the diseases (or disease categories) it examines, the committee will assess the state of knowledge of each disease and its potential to cause animal health, human health, and social or economic impacts. The committee will review the etiology of the disease, the nature of the responsible pathogen(s), evidence and mechanisms of intra- and interspecific transmission of the diseases, and currently available and potential methods of diagnostic testing. Domestic and foreign approaches to prevention, detection, and diagnosis will be examined. For this initial phase of the review, recommendations will be provided on how to improve the nation’s ability to address animal diseases by reducing potential for intentional or accidental introduction, enhancing diagnostic techniques and their use, and improving detection capabilities. Knowledge gaps and future needs for progress in systems and policies will be identified. |

report lays the foundation for two additional phases proposed for the study of the animal health framework (surveillance and monitoring in phase 2 and response and recovery in phase 3).

Given the complex, global, and sometimes rapidly changing nature of events affecting the animal health framework, the committee looked beyond farming and food-producing animals to consider a broader array of topics and players. For example, because of the emergence of new zoonoses with transmission routes through wildlife, such as West Nile virus, the committee’s approach includes threats to human and animal health from those sources. Beyond health concerns, the report also considers societal issues affected by animal disease outbreaks, such as economic impacts and food security. As a result, the report addresses a wide range and diversity of specific diseases from acute to chronic, endemic to exotic, and considers how naturally-occurring to intentionally spread might be handled. Box 1-2 presents a list of specific diseases examined in this report, which were selected to elaborate the need for an inclusive animal health infrastructure capable of preventing, detecting, and diagnosing a wide variety of animal health events.

Stakeholders with diverse perspectives involved in the animal health framework are the target audiences for this report, including animal producers, veterinarians, academic animal health educators and researchers, laboratory diagnosticians, state and federal elected officials, the public health community, state/local government officials, the technical community, policymakers, and the general public.

|

BOX 1-2 Exotic (Foreign) Animal Diseases Exotic Newcastle disease (END) Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) Recently Emergent Diseases Monkeypox Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) Endemic Diseases Chronic wasting disease (CWD) West Nile virus (WNV) Avian influenza (AI) Previously Unknown Agents Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus Novel Naturally Occurring or Bioengineered Animal Pathogens Diseases of Toxicological Origin |

Boundaries of the Report

This report is not a comprehensive, all-inclusive discussion of animal health. Rather, it is intended as a first step to begin an analysis that will be expanded and enriched in the second and third planned phases of this study.

For example, this phase of the study did not attempt an in-depth review of the effectiveness of each individual component of the framework or of any specific agency involved in safeguarding animal health but did examine the effectiveness of the framework as a whole in relation to different animal disease scenarios and, in doing so, sought to identify ways that the framework could be improved.

Early in its deliberations, the committee found that the topics of the first phase—prevention, detection, and diagnosis—are intimately intertwined with surveillance, monitoring, and response/recovery issues and that they are impossible to deal with in isolation. Because surveillance and monitoring are important to the prevention, detection, and diagnosis of disease, they are referenced in the report. However, this volume has not reviewed and presented recommendations for an overall surveillance system or the infrastructure that might be required for such as system,

because those issues are within the purview of the proposed second phase of this study.

General Terminology

This report contains numerous technical terms and acronyms or abbreviations (see Appendix A for Acronyms and Abbreviations; Appendix B for Glossary of Terms). Some of the general terms used frequently throughout the report are provided in Box 1-3, and a couple of them warrant additional clarification. The Statement of Task (Box 1-1) refers to “first-line responders”—individuals who play a key role in disease detection. Throughout this report, these individuals are identified as those on the front lines of detection, as described in Box 1-3.

|

BOX 1-3 Animal Health Framework: The collection of organizations and participants in the public and private sectors directly responsible for maintaining the health of all animals impacted by animal disease or that influence its determinants. Front-Line Detection: Almost anyone can play a role in front-line detection and prevention (e.g., a school bus driver who notices a sick animal in a nearby field), but front-line detection and prevention as used in this report refers specifically to those in a position most likely to be the first judge of an abnormal health situation in an animal or population and to initiate preventive action. They include people involved directly in animal production as well as field personnel involved in wildlife management. Those with close and direct animal contact and observation include ranch and farm workers, feeders, breeders, milkers, animal sales yard personnel, slaughterhouse inspectors, dealers, park rangers, zoo keepers, and companion animal owners. Exotic Animal Disease: Any animal disease caused by a disease agent that does not naturally occur in the United States (e.g., SARS, monkeypox). Foreign Animal Disease: An exotic animal disease limited to agricultural animals (e.g., foot-and-mouth disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy, rinderpest). Zoonoses: Diseases caused by infectious agents that can be transmitted between (or are shared by) animals and humans. |

The terms “exotic animal disease” and “foreign animal disease” are also used in the report and may be confusing to the reader. While the terms are essentially synonymous, each is commonly used and understood separately as part of the vernaculars of different organizations, cultures, and groups. Therefore, we have purposely elected to use both terms in the text of this report; Box 1-3 includes specific definitions of each of them.

BACKGROUND

Traditional Approaches for Preventing and Controlling Animal Diseases

Historically, measures taken at the national level to prevent animal diseases began at the country’s borders and focused inward. The federal agency charged with primary responsibility for overseeing disease initiatives for livestock and poultry has been the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS). The traditional mission of APHIS, “to protect American agriculture,” was carried out by channeling resources into three principal areas: adoption of quarantine measures to protect on-farm commodity production, implementation of emergency actions from the incursion of exotic diseases or related pests, and treatment to control or eliminate diseases and related pests.

The overall credibility of such efforts, with both domestic producers and other countries, hinged on the ability of APHIS, working with state counterparts, animal health professionals, and laboratories, to establish effective diagnostic systems, carry out continual inspection and surveillance, and respond to unforeseen emergencies from disease incursions. Ports of entry, inspection, and surveillance systems were established to prevent the introduction and spread of unwanted livestock and poultry diseases.

In addition to building and maintaining response capabilities, eradication programs were carried out for specific diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease, hog cholera, tuberculosis, brucellosis, and screw worm. Such programs required skilled expertise in specific disciplines such as veterinary medicine and were very labor-intensive. The disease profiles were generally well understood but required many years for complete eradication, which in some cases has still not been accomplished. Pockets of selected diseases, such as brucellosis and tuberculosis, still remain. Disease eradication campaigns required large financial outlays over a number of years, but to reduce exposure and protect growing export markets, campaigns for selected diseases such as foot-and-mouth or pests such as screw worm were funded and jointly carried out in other countries.

For many decades, this traditional approach looking at only livestock or poultry diseases—built on the presence or absence of specific diseases and supported by systems of inspection, diagnosis, and response—has served as the backbone of efforts to protect primary production. With the exception of ongoing screw worm eradication efforts in Central America and a relatively small workforce stationed across the world, direct financial support and involvement typical of the large international eradication campaigns of the past have been substantially scaled back or curtailed.1

While the animal health framework has been able to respond to a range of demands and challenges in the past, the pressures on animal health are increasing. In addition, there is a new recognition that wildlife and companion animals are playing a more important role in our lives and in the transmission of diseases that will further challenge the framework.

Changes Affecting the Animal Health Framework

Challenges to the animal health framework are, in part, the result of the transformation, restructuring, and fundamental changes in agriculture itself. A rapid consolidation in the agricultural sector is evident: the total number of U.S. farms declined from nearly 7 million at the beginning of the last century to less than 2 million today, while the average size of beef, dairy, pork, and poultry operations increased substantially (USDA, 2002c). At the same time, new sectors of animal agriculture (such as aquaculture and organically produced animals) are emerging. The last decade has also seen a marked increase in the number of fish raised in aquaculture facilities. In 2002, an estimated 6,653 farms (57 percent of which were less than 50 acres in size) produced 867 million pounds of aquaculture products (USDA, 2002c). Urban growth is increasingly encroaching on rural and wildlife environments, bringing populations of humans and animals, both farmed and wild, into closer and more frequent contact. Ecological systems and cultures that once were distinct are increasingly blurred at their borders, creating new opportunities for disease transmission and exchange at their interfaces. Furthermore, globalization has led to increased movement of products and animals worldwide and, by association, increased the potential for transmission of diseases and related pests between countries, while the genetic homogeneity of production animals may increase the vulnerability of the food

supply to catastrophic losses of disease. It is no longer sufficient to focus only on livestock or poultry, because many other species can be affected. Increasing population densities of domestic and some wild animal species have magnified the impact of infectious diseases.

One of animal agriculture’s most difficult shifts is likely to be a move from its past independence to a new interdependence. This shift will be characterized by a profound interconnectedness in which producers and agriculturalists will be influenced and impacted by environmentalists, animal welfare activists, public health officials, agribusinesses, trade officials, and consumers. Today’s agriculture is neither traditional nor in control of its own destiny. Increasingly, new sectors and special interest groups that have not been aligned or involved with agriculture in the past are now helping to shape its future. Policymakers, business leaders, and politicians—who are progressively more urban in thought and locale—envision animal agriculture and its future with a very different perspective. The complex, global, and intertwined world of contemporary agriculture will most certainly change the entire framework of animal health, how it operates, with whom it partners, and how it relates to a world that is rapidly closing in around it.

At the same time, an examination of the animal health system must assess its ability to coordinate and integrate actions within a larger group of participants who bring new perspectives and expectations for consideration. Inherent in this broadening scope and scale is the reality of emerging infectious diseases, new zoonoses, food safety problems, and the unfortunate reality that the intentional introduction of animal diseases could result in a cascading effect of potentially catastrophic consequences. The framework to address these diseases has increased in importance, complexity, and visibility. Certainly, the framework needs to be commensurate with, and responsive to, the profound forces and changes driving its future.

Relationships of Animal Diseases to Sectors beyond Production

The importance of animal diseases and related programs on domestic consumption, production, and trade has been well recognized, yet the impacts can include other dimensions and sectors such as food security, public health, market and product accessibility, economic viability, tourism, biotechnology, bioterrorism, and the environment.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) defines food security as “When all people at all times have both physical and economic access to sufficient food to meet their dietary needs for a productive and healthy life” (USAID, 1992). For the period 1999 to 2009, worldwide population is estimated to grow by 30 percent to 7.5 billion (IFPRI, 1999), and

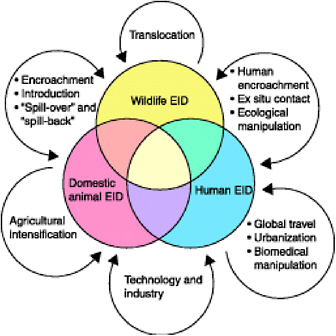

FIGURE 1-1 Interactions of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) with a continuum that includes wildlife, domestic animals, and human populations. Few diseases affect exclusively any one group, and the complex relations among host populations set the scene for disease emergence. Examples of EIDs that overlap these categories include Lyme disease (wildlife to domestic animals and humans) and rabies (all three categories). Companion animals are categorized in the domestic animal section of the continuum. Reprinted with permission from Daszak et al., Science 287:443-449 (2000). Copyright 2004, AAAS.

between 1997 and 2020, it is estimated that worldwide demand for meat may increase 55 percent (IFPRI, 2003). Increasing trade and the need to ensure food security underscore the dual objective in carrying out agricultural animal disease prevention and control initiatives: to evaluate imports so that domestic production is not put at greater risk of disease, and to ensure that such initiatives do not become a bottleneck for the flow of products, limit access to products, or hamper food security. Traditional programs have understood the first objective well, but the second role has received little attention.

The Interaction among Domestic Animals, Wildlife, and Humans

As illustrated in Figure 1-1, the animal health framework must now deal with a continuum of host-parasite relationships involving public

health, companion animals, wildlife, ecosystems, and food systems in an increasingly complex, global context.

Wildlife

Historically the attention paid to wildlife disease by regulatory agencies, wildlife advocacy groups, and educational and research institutions has been limited in comparison to that for domestic animals. However, the greatly increased contact among wildlife, domestic animals, and people associated with globalization and societal incursions into wildlife habitat has increased the opportunity for the transmission of pathogens shared within and among these domains. Increased population densities of people, domestic animals, and some wildlife species favored by human societal impacts on the environment, can make the situation even more precarious, because of the increased opportunity for transmission of infectious agents. For instance, expanding and increasingly dense poultry populations increase their chances of exposure to strains of avian influenza virus from wild waterfowl; expanding deer populations can support increased populations of deer ticks, which may spread Lyme disease where the causative agent (Borrelia bergdorferi) is endemic in the rodent population; and the periurban growth in raccoon populations increases the risk of rabies for humans and domestic animals. It is recognized that prevention and/or elimination of these disease interfaces is problematic, especially when steps to reduce wildlife populations can be difficult from both biological and sociological perspectives.

The host-parasite ecological continuum—described by Daszak et al. (2000) as a continuum where disease boundaries among wildlife, domestic animal, and human populations are increasingly blurred—provides a useful context in which to illustrate the importance of wildlife diseases and the pathogens they harbor in today’s world (see Figure 1-1). The framework for dealing with animal diseases in this continuum must involve a wide range of government agencies and stakeholders that have overlapping interests in disease involving wildlife, as well as people and domestic animals. Providing the administrative means for effective coordination among the elements of such a framework is a formidable challenge.

West Nile virus (WNV) in wild birds, SARS in civets, avian influenza in wild migratory water fowl, plague (Yersinia pestis) in wild rodents, and rabies in raccoons, skunks, and bats are but a few examples of pathogens harbored in wildlife that can be transmitted to humans and/or domestic animals (see Chapter 3 for case studies). Conversely, pathogens are also being transmitted from domestic animals to wildlife populations; for example, tuberculosis to deer, elk, and bison; brucellosis from elk and bison to cattle; and Mannheimia pneumonia (pasteurellosis) in bighorn and do-

mestic sheep (USAHA, 2003b). Tuberculosis in Michigan may have spilled back again from deer to infect cattle. In Yellowstone National Park, the presence of brucellosis in elk and bison is considered a potential threat to domesticated cattle grazing at the park boundaries (Dobson and Meagher, 1996). Zoo animals and exotic companion animals are also part of the disease continuum. For example, 58 zoo animals of 17 species in the United Kingdom acquired scrapie-like spongiform encephalopathies thought to result from exposure to feed contaminated by the BSE agent (Collinge et al, 1996; Kirkwood and Cunningham, 1994). Companion animal interaction with wildlife can also lead to transmission of pathogens, e.g., canine distemper to blackfooted ferrets (Thorne and Williams, 1988); feline leukemia virus to Florida panthers (JAVMA News, 2004); skunk rabies to cats; and a variety of parasitic helminths and protozoa to domestic livestock and people (Dubey and Lindsay, 1996; Waldner et al., 1999).

Translocation of both indigenous and exotic wildlife continues to be a major anthropogenic cause for the spread and impact of pathogens harbored in wildlife. This is a surprising circumstance because the danger inherent in such activity has been recognized for a long time. The dissemination of chronic wasting disease (CWD) and monkeypox are cases in point (see Chapter 3). Migratory wildlife can play a major role in spreading infectious agents as exemplified by rabies virus in mammals and avian influenza (AI) virus and Newcastle disease virus (NDV) in waterfowl.

During its deliberations the committee came to appreciate more fully the rapidly growing importance of wildlife as a source of infectious disease for people and domestic animals. While the committee had the expertise to assess the threat posed to humans and domestic animals by potential pathogens harbored in wildlife, it did not have members with sufficient knowledge of all the government agencies dealing with wildlife diseases to undertake a detailed assessment of their effectiveness. The federal and state responsibilities pertaining to all aspects of animal health and disease, including both domestic and wild terrestrial and aquatic animals, span such a wide array of government agencies that a detailed analysis of their functional relationships was beyond the practical capabilities of the committee. (For a chart of these agencies, see Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2.)

The committee recognized the importance of fish disease in both aquaculture (including coastal marine elements) and wildlife fishery. Aquaculture is the most rapidly growing livestock industry in the United States. Maintaining animal health is no less an issue for fish stock than for terrestrial animals. For example, recently the industry has had to cope with the introduction of exotic diseases such as infectious salmon anemia and spring viremia of carp in 2001 and 2002, respectively (USDA APHIS-VS, 2002; USDA, 2004c). Disease-related services at the federal level are

fragmented among the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS), the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Fish and Wildlife Service (DOI FWS), and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (DOC NOAA). The need for coordination among these agencies is being addressed at present by a task force that is actively developing a National Aquatic Animal Health Plan under the auspices of the Joint Subcommittee on Aquaculture and the National Science and Technology Council Committee on Science, to be completed in 2006 (USDA, 2004a).

The Convergence of Human and Animal Health

Diseases found in humans have always been intensely affected by human-animal interactions. In fact, it is accepted that many infections of humans have origins in common with animals (Childs and Strickland, 2000). Although there are some diseases that are transmitted between humans only (for example, syphilis), a large number of domestic animal diseases are shared with humans—60 percent of the 1,415 diseases found in humans are zoonotic, and most are “multispecies” for domestic animal diseases (Cleveland et al., 2001).

With the development of agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago and the domestication of dogs and later livestock, animals became a more prominent part of our lives. Although there is good evidence to suggest that the advent of agriculture brought with it the phenomenon of zoonotic diseases, a new era of emerging and reemerging zoonotic diseases appeared to begin several decades ago. Since the mid-1970s, approximately 75 percent of new emerging infectious diseases of humans have been caused by zoonotic pathogens. Similar to the time of animal domestication, which triggered the first zoonoses era a number of millennia ago, a group of factors and driving forces have created a special environment responsible for the dramatic upsurge of zoonoses today.

The transmission of animal diseases to humans most often occurs via food through poor hygiene or improper handling of animal products. Organisms that cause zoonoses (such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, and protozoa) can also be transmitted via air, water, and vectors such as mosquitoes. In the field of emerging diseases, vector-borne and rodent-borne diseases are especially notable since they remain major causes of morbidity and mortality in humans in the tropical world and include a large proportion of the newly emerged diseases (IOM, 2003). The spectrum of vector-borne diseases are from animal-to-animal (bluetongue), animal-to-human (WNV), or human-to-human (dengue). It has been estimated that one tick-borne disease has emerged in the United States every decade for the past 100 years (IOM, 2003).

Some scientists argue that, of the more than 30 emerging diseases recognized since 1970, none are truly “new” but instead only newly spread to the human population (Saritelli, 2001). Today, new human behaviors create new risks for animal disease transmission to humans; for example, the feeding of animal by-products to cattle (which are herbivores) allowed BSE to emerge and spread to beef-eating humans, and the xenotransplantation of animal organs into humans raises concerns. The industrialization of food production, while making standardization of food easier, has created opportunities for large-scale microbial colonization in food animals and subsequent large-scale food contamination with pathogens, such as salmonella and E. coli O157:H7. Even when concerns are raised prior to transmission, action is not often taken. For example, it could have been predicted before 2003 that the importation of African rodents, including giant Gambian pouched rats, from areas where rodents are known to carry monkeypox would introduce monkeypox virus into the United States and potentially spread to humans. Today these pouched rats are being trained to detect landmines (Wines, 2004). If these trained rats are sent to various regions of the world to assist with landmine removal but precautions are not taken to ensure that they do not carry the monkeypox virus, monkeypox may spread to rodents and humans elsewhere in the world.

The confluence of people, animals, and animal products within today’s dynamic international context is unprecedented, and we continue to face new microbial threats, as evidence by a recent outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 in a group of children who were exposed in a petting zoo, a Marburg virus outbreak in Angola, and the monitoring of H5N1 avian influenza in Southeast Asia as a potential pandemic strain. These concurrent events underscore the importance of new scientific and programmatic partnerships between veterinarians and public health officials and should serve as an impetus for the animal health framework to ensure a new capacity and focus that will address emerging and reemerging zoonoses.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The next three chapters of this report review, summarize, and evaluate the state and quality of the current system for safeguarding animal health and the potential for improved application of scientific knowledge and tools. Chapter 2 provides a general overview of the animal health framework, supplemented by Appendix C, which contains additional details on the existing federal system for addressing animal diseases. Chapter 2 is also intended to supply the context for the entire three-phased initiative, and as such, includes issues relevant to surveillance, monitoring, response, and recovery. Chapter 3 focuses on prevention, detection,

and diagnosis, exploring past experiences with a number of specific animal diseases. Based on the analysis of that experience, Chapter 4 considers current capabilities and limitations of the existing animal health framework and identifies key gaps in our ability to prevent, detect, and diagnose animal diseases. Finally, Chapter 5 provides recommendations for strengthening the existing system and identifies opportunities and needs for front-line prevention, detection, and diagnosis.