3

Pillar Two: Meeting Pathogen Research Challenges

Effective surveillance and response programs of industrialized nations must be supported by a solid research base that draws not only on the capabilities of researchers within the country, but also on the findings of the broader international scientific community. Research is particularly important when considering those infectious agents that are newly identified, either within nature or as the result of bioterrorism-related activities. At the same time, there are many unanswered questions concerning even common disease agents.

Coupling solid fundamental research with targeted applied research is also beneficial to Russia’s national goals and those of the international community in the biosciences and public health. Specifically, applied research efforts can help:

-

evaluate test methods and other tools, including epidemiology and forensics, to identify and understand endemic and newly emerging infectious agents of human and agricultural importance

-

identify the behaviors, environments, and host factors, including chronic diseases, that put people and animals at risk of infections

-

develop and evaluate prevention and control strategies, including disinfectant approaches, vector control measures, and the use of vaccines and drugs

Such applied research activities build upon the results of fundamental research activities conducted both domestically and internationally (CDC, 1998a; Maksimova, 2003).

RUSSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS

For decades, the Soviet and then Russian governments have supported many dozens of large public research institutes with programs that address the foregoing and related challenges of infectious diseases. Appendix J identifies a number of the principal research institutes that are currently involved in this large national effort. Most are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health and Social Development, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, and the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences. A few that were previously state institutes have been privatized, although the government retains a substantial percentage of ownership in some. In addition, a number of Russian universities and other institutions of higher education have important biological research activities. A handful of commercial organizations, such as those in the veterinary sciences, are also beginning to recognize the importance of supporting applied research at universities.

Most Russian research institutes relevant to this study have applied research programs designed to directly support public health or agricultural activities. A few are oriented toward developing products for the commercial marketplace, although most continue to look to government organizations as their principal clients—and therefore the funders—of research. As indicated in Appendix J, a few institutes have been designated by the government as State Research Centers with access to special funds available through the Ministry of Education and Science.

One of the largest centrally coordinated research efforts in the field of infectious diseases directed toward the improvement of general approaches to disease prevention and control was organized by the former Ministry of Health and is now under the purview of the Ministry of Health and Social Development. Several research institutes of the ministry and numerous institutes of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences are involved (see Appendix J). The following research areas have received primary attention:

-

fundamental and applied research in medical microbiology, virology, immunology, epidemiology, parasitology, and disinfection

-

improvement of the nationwide epidemiological surveillance system (previously discussed in Chapter 2)

-

development of new preparations and methods for diagnosis, vaccine prophylaxis, and drug-based prophylaxis

-

improvement of the prevention system and anti-epidemic measures consistent with regional characteristics of infectious pathology

This program has claimed many successes even in recent years when budgets were severely constrained. Specifically, Russian officials point to the following successes: the development of several dozen new medical vaccines and drugs

now in various phases of investigation; the preparation of approximately 50 sets of methodological instructions and recommendations; the publication of 40 handbooks for physicians; and the promulgation of a dozen regulations and rules to protect sanitary conditions in the research environment. About 100 applications for Russian patents developed within the framework of the program have been approved or are in the approval process. Appendix K describes other recent achievements of the program (Onishchenko, 2002).

Also worthy of mention in the context of disease-related research is the complex of research and production facilities that retain a relationship with Biopreparat (see Appendices J). Biopreparat is best known for its Soviet era role in biodefense activities. In the early 1990s, the Russian government redefined its mission to develop and produce medical products, primarily for the Russian market. The Biopreparat complex has been largely privatized with the Russian government retaining a significant number of shares in most institutes, which now are loosely affiliated with the Ministry of Health and Social Development. The Institute of Applied Microbiology in Obolensk and the Institute for Applied Biotechnology and Virology “Vector” in Koltsovo report to the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Social Welfare, a division of the Ministry of Health and Social Development. This should enhance the research and diagnostic capabilities of that service.

Most, if not all, of the Biopreparat institutions were involved in Soviet biodefense programs until the early 1990s under the USSR Ministry of Medical and Microbiological Industry. At their peak, they employed tens of thousands of scientists, engineers, technicians, and service personnel. With lucrative funding, they developed strong capabilities that are relevant to infectious disease diagnosis, prevention, and therapy. Government-sponsored programs should draw more broadly on the underutilized research capabilities of Biopreparat institutions, as the researchers become more acclimated to working with colleagues from other Russian institutes that have always been civilian oriented.

An important research priority at the Biopreparat institute “Vector” is the investigation of smallpox. This disease has been identified by the Russian government as a serious bioterrorism threat. For many years, Russia has hosted one of the two worldwide repositories for smallpox strains. Russian officials believe that their researchers can make significant contributions in characterizing smallpox and assisting in developing antidotes which would be very important in responding to an incident should illegally obtained strains fall into the hands of terrorists.

Turning to the agricultural system, the Ministry of Agriculture has several relevant research institutes under its direct control. For example, a veterinary sciences institute in Vladimir is studying foot-and-mouth disease; another in Kazan, brucellosis; and a third in Pokrov, rabies and related diseases. Under the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences there are all-Russian institutes, zonal institutes, and veterinary research stations that further extend disease-related capabilities (see Appendix J for a list of institutes).

TABLE 3.1 Evolution of Regulatory Framework for Genetic Engineering in Russia

|

Year |

Regulation |

|

1996 |

Federal Act “State Regulation of Genetic Engineering Study,” Adopted |

|

2000 |

Federal Act “State Regulation of Genetic Engineering Activity,” Amended |

|

2000 |

Instruction by Chief State Sanitary Physician of Russia “Hygienic Expertise of Food Products Derived from Genetically Modified Organisms,” Issued 2001 Order by Government of Russia “State Registration of Genetically Modified Organisms,” Issued |

|

2002 |

Order by Government of Russia “State Registration of Feeds, Derived from Genetically Modified Organisms,” Issued |

|

2003 |

Order by Chief State Sanitary Physician of Russia “Microbiology Molecular-Genetic Expertise of Genetically Modified Microorganisms Used in Food Production,” Issued |

|

SOURCE: Center for Bioengineering, Russian Academy of Sciences (November 2003). |

|

As for plant protection, ministry institutes address broadly defined disease and quarantine issues. Institutes under the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences conduct research for the optimization of phytosanitary conditions based on integrated pest management, chemical control, and biological control. The principal research institutes in this field are listed in Appendix J.

In the relatively new research area of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), more than 80 institutes and higher education institutions have established research review committees, indicating widespread interest in this frontier area of science. As the result of a nationwide competition for cutting-edge projects in all fields of applied research in the spring of 2003, the former Ministry of Industry, Science, and Technology awarded a substantial grant to the Bioengineering Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences for work on genetic modifications of potatoes, sugar beets, soybeans, and other crops with disease-resistance being one of the objectives (for a list of other proposed projects, see Appendix L). Table 3.1 identifies the key Russian laws on GMOs.

Finally, the Russian Academy of Sciences has traditionally played the leading role in fundamental science, particularly in microbiology, biochemistry, and virology. In the last few years, however, the pressure of drastically reduced budgets forced some of the academy’s institutes to reorient much of their basic research toward more practical applied activities. Some have been successful in attracting domestic and international funding to support efforts with near-term applications, but a few institutes remain focused almost exclusively on basic science. Appendix J identifies a number of institutes with programs relevant, directly or indirectly, to infectious diseases. Many of the Academy’s strongest biology institutes are in the city of Moscow and in the Pushchino area of the Moscow region.

DECLINE IN RUSSIAN RESEARCH CAPABILITIES

Unfortunately, since 1990 one of the primary metrics for determining budgets of government research organizations, including academies of sciences and ministries with affiliated research institutes, has been the number of their institutes dependent on federal funds and the number of employees within these institutes. Too often quality and significance of research have been set aside in favor of maintaining the largest possible payroll. According to some Russian scientists, this is a widespread approach among Russian research managers, particularly the older generation, who believe they have a social responsibility to their staff members that have no employment possibilities beyond current positions, however depressed pay scales may be.

Still, during the past decade, almost all Russian research institutes have experienced significant downsizing as many of the most entrepreneurial scientists have found better paying jobs elsewhere. In some, the scientific staff has been reduced by more than one-half. A number of the best researchers, faced with evaporating salaries and malfunctioning equipment, have either abandoned their scientific careers or moved abroad in search of opportunities to continue working at the frontiers of science. The flight of scientists is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

In Russia’s research institutes, the base salary of laboratory directors in 2003 was equivalent to about $200 per month and that of senior scientists $150 per month, far less than industrial workers received for example. Some entrepreneurial researchers were able to supplement these base salaries with income from international or Russian grants, but many researchers and support staff did not have access to salary supplements. As for equipment, one estimate indicates that most institutes had less than 65 percent of the laboratory bench instruments needed for effective fulfillment of their research programs, 75 percent of the needed computers, and 10 percent of the required large equipment (Zverev, 2003).

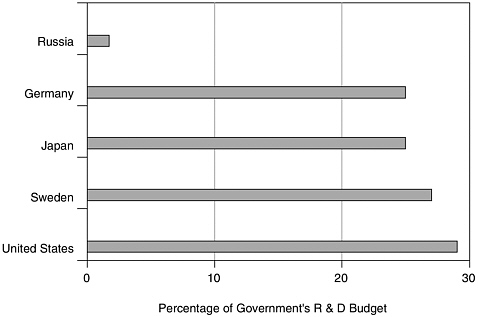

On average, the government provides about one-half of the operating budgets of state research institutes; those budgets have less purchasing power than in the Soviet era (see Figure 3.1 for an indication of the relative low priority accorded research in the medical sciences in Russia today). The special programs of various ministries, international grants, one-time equipment allocations by the government, and the income from rental space and health-related services offered at the facilities cover most of the remaining 50 percent.

Examples exist of both financially stable research institutes—such as the Institute of Highly Pure Biopreparations, the Englegardt Institute of Molecular Biology, and the Institute of Epidemiology—and institutes that have approached the brink of bankruptcy, for example, the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk. The sharp rise in the cost of electricity poses a pressing financial problem for almost all institutes with no easy solution. Often, in order to pay energy bills, institutes reduce scheduled purchases of needed modern laboratory equipment or even reduce the working hours at the facilities.

FIGURE 3.1 Medical sciences share of government-sponsored academic R&D. SOURCE: Science and Engineering Indicators, National Science Foundation (2004).

But financial constraints on domestic activities are not the only problem confronting Russian research institutes. Participation in activities of the international scientific community also presents enormous difficulties. First, coordination with the activities of the international community is sometimes weak, and at times experiments already conducted abroad have been repeated unnecessarily in Russia because international publications were not available during the design of Russian experiments. Second, export control barriers hamper exchanges of biological materials, strains, technologies, and genomic databases. The United States is the strongest proponent of stringency in protecting these items that could be of interest to terrorist groups. But as Russia tightens export controls, foreign partners are increasingly denied access to Russian resources. Third, while Internet access is becoming more commonplace in Russia, few funds are available for attendance at international conferences or for short study trips abroad.

ADVANCING LABORATORY RESEARCH

Russian colleagues have admirable ambitions for elevating Russian research to the global level in the future. They recognize that applying advances in nanotechnology, new materials, and information technology to biotechnology,

for example, could create systems and devices with large benefits for health, personal safety, business, and trade. They advocate the need for Russian researchers to concentrate on daunting challenges such as

-

DNA sequencing and analysis for molecular diagnosis of diseases, identification of molecular markers, disease prediction through gene typing, and genetic methods for combating diseases

-

GMOs not only for agricultural crops but also for the production of insulin, interferon, and edible vaccines

-

use of high-resolution physical methods to develop new approaches to therapy for controlling the immune system and overcoming drug addiction

-

engineering for treatment of heart disease and for xenotransplantation of organs, tissues, and cells, including those from genetically modified animals

They point out that it is better for Russian scientists to be working on these topics in collaboration with international colleagues than to be caught by surprise by discoveries of international colleagues (Sandakhchiev, 2003).

Although this is a laudable agenda, it would stretch current Russian capabilities beyond realistic near-term limits. Conducting frontier research in more traditional areas, let alone undertaking internationally competitive efforts in advanced fields of science, will require concerted efforts by the best laboratory teams in the country. These teams need substantial financial support, primarily from the Russian government.

Unfortunately, many of the strong research teams of the past have disappeared and have not been replaced. Those that have remained in place have been weakened by the loss of experts and the degradation of equipment capabilities. Nevertheless, there are still areas of very strong Russian research capability. However, in the absence of much greater and more highly focused government efforts to adequately support even a limited number of research teams, Russian research will have declining significance for the international community and for Russia.

Because the Russian government is unable to provide an adequate level of support for its large complex of research institutes in the near term and possibly even in the long term, the Ministry of Education and Science has proposed closing the less productive research institutes and redirecting these funds to the stronger ones. Closing institutes is difficult for both political and social reasons. Strong arguments exist for maintaining broadly based research capabilities to address infectious diseases in different ecological zones. Also, no local politician is prepared to accept closure of an institute in his or her region since most employees of institutes have no other places for employment and little opportunity to relocate.

The government’s designation of a few institutes as State Research Centers one decade ago and the promise to channel substantial special funds to these

institutes was an attempt to support the best scientific teams to the fullest extent possible. However, the anticipated funding levels were not realized, and the selection of entire institutes that may have had hundreds of unproductive scientists dependent on the high productivity of outstanding scientific coworkers proved to be an ineffective approach. In addition, in open competitions, Western funders frequently select recipients of grants based on the quality of the achievements by individual researchers rather than on the status of his/her institute. At the same time, most external funders are so focused on near-term project results that they do not adequately consider the long term viability of the institutes’ laboratories and supporting infrastructure.

The approach of focusing on laboratories of excellence advocated by the committee does not call for closing other research entities, which of course is a significant issue that can only be addressed by the Russian government. Focusing a significant portion of available resources more sharply on the most promising research groups should enable these laboratories to undertake additional programs of public health importance and thereby foster high standards of achievement. In time, this approach may put pressure on traditional funders to reduce support for less productive groups. Such reductions of support might lead to the consolidation or closing of laboratories that are not productive, thereby releasing additional funds for more productive programs. Competition between researchers for resources would stimulate productivity, regardless of the level of available resources. The alternative approach of continuing to spread available resources over laboratories in all relevant research institutions, would continue a tradition that has led to the current decline in research productivity throughout the country and inadequate support of public health needs.

Against this background, the committee recommends an expanded effort by the Russian government, with the assistance of external funders, to focus laboratory research in order to more effectively advance public health and the control of agricultural diseases.

First, it is important to concentrate financial support on carefully selected research groups that are, or have the potential to become, centers of scientific excellence. Several hundred key Russian laboratories, each of which employs one or more integrated groups of scientists working toward common goals are, or could be, core elements of the Russian public health and agriculture research infrastructures of the future. Such important laboratories warrant special financial support granted through a competitive peer review process to enhance the research programs of their research groups.

Criteria for determining special financial support might include: (1) scientific excellence and relevance of research activities to public health and agricultural priorities of the government; (2) recent achievements of the research groups in advancing specific areas of science and in contributing to important human, animal, and plant disease prevention and control programs of the Russian government; (3) demonstrated capabilities of the scientific staff, particularly the rising

young scientific leaders within the research groups; and (4) a tradition of cooperating with and facilitating the development of other Russian research groups with related interests.

A second initiative is to upgrade facilities and equipment for appropriate disease-related research at selected laboratories throughout the country. Recent emphasis in Russia on using limited available funds primarily to meet payrolls has been accompanied by a dramatic decline in the facility and equipment assets of research institutions, including capabilities to maintain and disseminate data and to communicate rapidly domestically and internationally. As noted, increasing energy costs will further divert funds from support of equipment needs. This erosion of equipment capabilities has, in turn, contributed to a loss of Russian competitiveness in the search for international financial support as well as a decline in research productivity. Meanwhile, many of the best Russian scientists have emigrated to foreign laboratories where they can work using modern equipment.

The costs of adequately equipping even the several hundred laboratories which would house centers of excellence would be very high, and the primary source of funds must be the Russian government. Therefore, a fair and open competitive process for selecting recipients of funding is essential. This process should lead to a concentration of modern equipment to support the strongest research groups. Training to ensure optimum use of equipment would also be an important component of programs that provide equipment.

Laboratories that house research groups may normally compete for equipment and facility grants although on occasion, it may be appropriate for an entire institute to seek large grants that support activities in several laboratories. In addition, individual research groups would compete for research grants. The research centers of excellence would therefore emerge as the result of success in these two types of competitions.

With several exceptions, Russian ministries, agencies, and academies currently provide research funds to institutions, not directly to research groups or laboratories. Institute directors then play a central role in determining how funds are allocated within the institute. However, this central control has been weakened considerably during the past decade as many external funders now allocate funds directly to research groups and even to individual researchers with the approval of institute directors. The recommendations in this report, if implemented, should follow this new pattern. Reluctance of most directors to allow direct funding of their research groups should, in most cases, dissipate when their researchers have opportunities to compete for funds that would not otherwise be available.

As indicated in Box 3.1, some institute directors need no encouragement to embrace centers of excellence. But there have been examples of other institute directors refusing funding that they could not personally control; there are also examples of merit-based Russian grant competitions degenerating into programs

|

BOX 3.1 “If an institute director is interested in advancing the agenda of his own institute as a whole and has talent for pursuing that objective, then the director will not really have to be guided forward through any laboratories-of-excellence-type mechanism. In fact, there will certainly be prototypes of such laboratories already functioning in his institute.” SOURCE: Russian manager of biological research programs (October 2004). |

that have stretched grant funds so widely in an effort to support as many researchers as possible that individual grants have had little impact. There are counter examples of institute directors who have fully supported direct grants to individual researchers. This is evidenced by the Russian directors of dozens of institutes involved in infectious disease research who have endorsed grant payments by the International Science and Technology Center in Moscow directly to thousands of Russian researchers in their institutes.

These steps can contribute to developing the modern scientific basis that will enable Russia to work more effectively with the international community to implement an infectious disease research agenda that contributes in new ways to understanding the role of genetic, environmental, clinical, social, and economic factors in the emergence of diseases.

Sources of financing are the essential aspects of these recommendations. A realistic approach to funding these recommendations for an initial period of five years would be a combination of Russian government resources and a loan from the World Bank or the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The World Bank has in the past, when requested by host governments in Central Europe and other regions, provided loans in the tens of millions of dollars to support research grant programs and programs for upgrading scientific infrastructures.

Should one of these development banks be asked by the Russian government to support the approach of selective financing for centers of excellence, few directors of high quality Russian institutes are likely to remain resistant, entrenched in past approaches. The stakes would be too high not to participate. Those directors who sit on the sidelines would soon become recognized as working on the basis of evaporating hopes of the past and not the basis of present and future realities. Even if the banks are not responsive due to Russia’s improved

economic condition, the Russian government itself is becoming an increasingly likely source of new financial support for such efforts.

In summary, there is a clear need to change current patterns of Russian funding for research in biology and other disciplines relevant to controlling infectious diseases. An important criterion for the allocation of available resources to research groups is their likely impact not only on scientific advancement but also on economic and social progress. No longer can science be simply an afterthought in the funding process with allocations based on “whatever-is-left-over.” Rather, to be leaders, the Russian scientific community needs to show in very specific and persuasive ways how it is making major strides toward meeting the health-related needs of the Russian people.