4

Pillar Three: The Promise of Biotechnology

As the context for Russian industrial activities steadily incorporates principles of market economics, many public and private customers for pharmaceutical products are continually reconsidering which products they purchase and at what prices. An abundance of imported products are readily available in Russia while consumer confidence in goods made in Russia has declined. Russian scientists and manufacturers are having difficulty keeping pace with advances in technology throughout the world. Thus, it is not surprising that domestic enterprises which manufacture products for protecting human health are operating at less than 25 percent of capacity and that many production lines are now outmoded. Similar problems exist in the agricultural sector where government support of state enterprises has also greatly declined.

This chapter provides a brief overview of the commercial and regulatory environment for the pharmaceutical/biotechnology sector as it develops in Russia. There is considerable interest in Russia in developing and producing vaccines, drugs, test kits, and other products for both the domestic and international markets. But the challenges are formidable, and Russia is far behind many other countries in reaching international customers. Nevertheless the committee has observed encouraging signs of new entrepreneurship and believes that during the next decade, Russia will begin to emerge as a significant contributor in this field, probably relying heavily on joint ventures with international companies. While imported products will continue to have a major presence in the Russian pharmaceutical/biotechnology market, a stronger domestic presence should improve the overall infrastructure for more effectively combating infectious diseases in the country.

Further, this chapter first describes the Russian marketplace for drugs, vaccines, and test systems. It highlights the role of the Biopreparat complex, which was a focal point for Soviet defense-related activities, and the role of Biopreparat-affiliated institutions in cooperative U.S.-Russian nonproliferation research programs. After noting some of the key aspects of the evolving regulatory framework in Russia, it highlights the gap between research activities sponsored by the Russian government and commercial production activities. It then offers several suggestions for facilitating development of the biotechnology sector in Russia.

THE MARKET FOR MEDICAL PRODUCTS IN RUSSIA

Medical Products for Humans

According to Russian estimates,1 the market in Russia for drugs intended for human consumption (valued at the point of use) rose from $2.5 billion in 1999 to $3.7 billion in 2002, with a projection of $5.0 billion in 2005. This growth has been attributed largely to higher consumer earnings. About 60 percent of the costs were carried by consumers. Various state organizations covered the remaining 40 percent. About 70 percent of drugs were distributed by prescription and 30 percent were over-the-counter items. Approximately 70 percent of drugs (by cost) were imported. This figure reflects the emphasis of Russian producers on cheap generics while expensive specialty drugs largely come from abroad. Among the principal obstacles to the further development of markets in Russia—both for foreign and domestic manufacturers—are a lack of transparency in the registration, certification, and licensing systems; inadequacies in the protection of intellectual property; and the large quantity of counterfeit medicines.

Of the top 20 producers of drugs in Russia in 2002,2 only two companies were Russian-owned: Akrikhin (also known as Otechestvennoe Lekarstvo) and Marbiofarm, the Russian branch of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International (formerly ICN Pharmaceuticals). Other Russian producers were Firma Bryntsalov and Moskhimfarmpreparaty. As for imports, the market has become less concentrated, with the total market share of the top five importing companies decreasing from 25 percent in 2001 to 19 percent in 2002 (Maksimova, 2003).

Domestic production of vaccines for use in humans increased to a sales level of $48 million in 2002 from $44 million in 2001. Meanwhile, imports decreased from a value of $52 million in 2001 to $33 million in 2002. The fluctuation in imports is partially explained by increased sales in 2001 in anticipation of new taxes in 2002, and then a decline in 2002 as a result of those taxes. Only a very small fraction of sales were to pharmacies and hospitals (7 million rubles or about $225,000), because vaccinations are administered primarily in polyclinics, pre-school and school health facilities, and medical centers of enterprises. Important anti-viral vaccines produced in Russia are identified in Table 4.1, and manufacturers are identified in Table 4.2. Tables 4.1 and 4.2 provide a summary overview of the limited vaccine production in Russia and suggest that there are considerable opportunities to increase such production.

In short, the value of vaccines produced and consumed in Russia is very small in comparison with the value of drugs. Yet, according to the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, research efforts devoted to vaccines far exceed the extent of research on drugs, highlighting the disconnect between research and commercialization of products. While the research on vaccines is important, there should also be important new opportunities to expand drug-related research in support of the Russian-based pharmaceutical industry.

As for diagnostic test systems, domestic production was estimated at $16 million in 2002, 31 percent higher than in 2001. Imports remained steady at about $5 million. The increase was initially largely attributed to a growing demand for HIV/AIDS test systems. Purchases by the Russian government of HIV/AIDS test

TABLE 4.1 Important Anti-viral Vaccines Produced in Russia, 2002

|

Vaccine |

Sales (millions of U.S.$) |

Share of Sales (percent) |

|

Viral hepatitis B, Recombinant DNA |

20.0 |

42 |

|

Influenza, trivalent polymer-sub-isolated, liquid (Grippol) |

5.7 |

12 |

|

Anti-rabies |

2.6 |

5 |

|

Tick-borne encephalitis, cultured, cleaned, concentrated, inactivated, dry |

2.5 |

5 |

|

Mumps, cultured, live, dry |

2.3 |

5 |

|

Influenza, allantois, live, intranasal, for children |

1.9 |

4 |

|

Poliomyelitis, peroral 1, 2, and 3 types |

1.7 |

4 |

|

Mumps-measles, cell-cultured |

1.7 |

3 |

|

Measles, cell-cultured |

1.6 |

3 |

|

Viral hepatitis A |

1.3 |

2 |

|

SOURCE: TEMPO Noncommercial Partnership Center of Modern Medical Technology, 2003. Also, www.gsen.ru lists all vaccines licensed in Russia, both domestic and imported. These include diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis, for example. |

||

TABLE 4.2 Leading Producers of Vaccines in Russia, 2002

|

Producer |

Sales Volume (millions of U.S.$) |

Share in Vaccine Sales Volume (percent) |

|

Solvay Pharma |

4.28 |

48.9 |

|

GlaxoSmithKline |

1.33 |

15.2 |

|

Immunopreparat |

0.55 |

6.3 |

|

ICI Pharmaceuticals Inc. |

0.49 |

5.6 |

|

Pasteur Merieux Connaught |

0.44 |

5.0 |

|

Virion |

0.32 |

3.6 |

|

St. Petersburg’s Scientific Research Institute of Vaccines and Serums |

0.19 |

2.2 |

|

Institute Merieux |

0.11 |

1.3 |

|

Chumakov Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis |

0.06 |

0.7 |

|

Chiron Behring GmbH and Co. |

0.04 |

0.5 |

|

SOURCE: TEMPO Noncommercial Partnership Center of Modern Medical Technology, 2003:21. NOTE: The producers are primarily foreign-owned companies which generally have higher sales (by cost) due to the higher prices charged than those charged by Russian manufacturers. The following domestic manufacturers produce limited quantities of vaccines: Vector (measles and hepatitis A); Enterprise for Production of Bacterial and Viral Preparations, Moscow (measles and mumps); NPO BIOMED, Perm (DPT); COMBIOTECH, Moscow (hepatitis B). In addition, the Microgen State Unitary Enterprise links about 20 production facilities which produce a substantial portion of Russia’s vaccines. |

||

kits has not increased significantly in the past several years, however; but there has been an increase in the assortment of test kits offered, including those for polymerase chain reaction systems.

A small percentage of test kits has been sold through pharmacies and hospitals. Most are purchased through state procurements for health departments and polyclinics. Twenty percent of sales were directly related to infectious diseases. Among the 20 companies in Russia that produce diagnostic kits of good quality are BIOSERVICE (Moscow), Diagnosticheskie Sistemi (Nizhnii Novgorod), ECOLAB (Moscow Region), and MBS and VECTOR-BEST (near Novosibirsk). These and others are listed on several Web sites (www.fcgen.ru; www.vector-best.ru; www.npods.ru; www.mbu.ru; www.mbu.ru; www.ekolab.ru). Appendix M identifies some of the many test systems currently manufactured in Russia.

Sales of products related to the treatment of prevalent human diseases are as follows. Domestically produced preparations for treating hepatitis rose considerably from 2001 to 2002, with vaccines increasing 150 percent and immunomodulators four-fold. Sales of both domestic and imported tuberculosis diagnostic preparations fell considerably from 2001 to 2002. Although the value of sales to pharmacies and hospitals increased, this growth largely reflected an increase in

|

BOX 4.1 The Joint Stock Company Biopreparat integrates 20 industrial enterprises that manufacture one thousand different products. The annual volume of commodity output, which is increasing, amounts today to over 10 billion rubles per year. Biopreparat accounts for nearly 35 percent of Russia’s total output of medical products, valued at more than 8 billion rubles in drugs and 1.7 billion rubles in medical engineering articles. Over 36,000 people are engaged in production. In Russia, Biopreparat leads in manufacturing certain drugs such as antibiotics and substances for their production, organic preparations, infusion solutions, and blood substitutes. The following companies fall within the Biopreparat complex: “Sintz” Joint-Stock Commercial Company, Kurgan; “Moskhimfarmpreparaty” FGUP, Moscow; “Biosintez” Open Joint-Stock Company, Penza; “Biokhimik” Open Joint-Stock Company, Saransk and; “Krasfarma” Open Joint-Stock Company, Krasnoyarsk. NOTE: Exchange rate in 2003 was approximately 30.7 rubles = $1. SOURCE: Adapted from BIOPREPARAT booklet obtained in Moscow in June 2003. |

taxes. Diabetes treatment drugs represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the pharmaceutical market, even though imports continue to dominate. Insulin makes up a large percentage of sales. Finally, cancer treatment preparations also represent a growing consumer demand, particularly for immunomodulators and hormone-free anti-tumor preparations (TEMPO Noncommercial Partnership Center of Modern Medical Technology, 2003).

Finally, the Biopreparat Complex (discussed more fully in Chapter 3) deserves particular attention in the discussion of Russia’s pharmaceutical market since it has been a focal point for U.S.-supported nonproliferation programs. Box 4.1 highlights its industrial activities.

Of immediate concern to domestic producers of vaccines, drugs, and other medical products is the new Russian legal requirement that by 2005 all production facilities must comply with the regulations calling for Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). Also, data supporting applications to produce new products must be based on work in laboratories complying with Good Laboratory Practices. Highlighting the problem, 10 domestic factories and institutes were producing different vaccines in 2003, but only one met GMP standards (Zverev, 2003).

Medical Products Related to Animals and Plants

Comparable data are not readily available on the production of vaccines and drugs for animal diseases. A major producer is the government-owned conglomerate RosAgroBioProm, which at one time had a dozen factories. Each factory employed hundreds and even thousands of workers. These factories have retained only a limited degree of stability during the economic slump of the past decade, and some are on the verge of bankruptcy. Appendix N identifies the principal production facilities of RosAgroBioProm.

The cornerstone legislation governing medicines in the agriculture sector, the Medicinal Drug Law, is the same as the legislation for medicines in the human health sector. Issues related to registration, certification, and selective control are very similar, as are the mechanisms of production certification, verification, and control of drugs. A Veterinary Council for Pharmacology and Biology serves as the regulatory body.

There are only a few manufacturers of animal medicines in Russia, and they are unable to satisfy market demand. RosAgroBioProm has eight operating plants, the Ministry of Agriculture has one institute producing medicines, and the Academy of Agricultural Sciences also has one such institute. In addition, four private companies are operating in Russia. Several joint ventures involve foreign partners (Bayer, Intervet, IDEXX, KPL), but they largely assemble raw materials from active ingredients produced abroad.

The government is a minor customer for agrodrugs, with the Ministry of Agriculture purchasing $3 million in drugs in 2003. The bulk of agrodrugs are purchased by privately owned agricultural enterprises or by joint stock companies.

While privatization of agricultural land has fallen behind other privatization efforts, practically all businesses engaged in animal husbandry are non-state organizations, specifically private enterprises and joint stock companies privatized in the early 1990s. Land is leased to these businesses on a long-term basis. Almost every animal for which veterinary services products are procured is privately owned.

Finally, the State Veterinary Service is very interested in high-quality drugs to ensure a favorable epizootic situation. While there may be concerns regarding the fairness of government procurement policies for vaccines and drugs, the Service seems determined to advance science in the direction of protecting animal health.

With regard to plant diseases there is only limited industrial capability to support plant protection programs. Most herbicides and insecticides are imported. Limited efforts are being made to develop green pesticides, using natural ingredients as an alternative to synthetically designed pesticides with severe environmental side effects. But, overall, the quality of Russian products falls behind those from abroad.

The Regulatory Framework

The laws and regulations governing the production and distribution of vaccines, drugs, diagnostic kits, and other medical products for application to humans and animals are extensive in Russia, as in other countries. Russian laws and regulations address areas of great familiarity to Western professionals in the field although many detailed requirements of implementation are unique to Russia. The many problems that new organizations, particularly those not linked to the government, encounter in understanding these regulations pose a formidable challenge.

The following topics are addressed by the Russian regulatory framework (TEMPO Noncommercial Partnership Center of Modern Medical Technology, 2003):

-

registration of foreign and domestic drugs and annual certification of conformity to reference specimens

-

licensing of trade in pharmaceutical products and associated quality control measures

-

coordination of retail prices with government ministries

-

import and export of drugs and precursors

-

lists of vitally needed drugs that receive tax and other special considerations

-

insurance policies for drug coverage

-

clinical tests of drugs, including preliminary studies of properties, preclinical investigations, and clinical trials

-

value-added taxes and exemptions for pharmacies and other organizations

-

requirements for good manufacturing practices at production facilities

-

advertising limitations

-

intellectual property rights

-

efficacy requirements

THE GAP BETWEEN RESEARCH AND PRODUCTION

As noted in this and previous chapters, many research institutes have been working on the development of new vaccines, drugs, diagnostic test kits, and other items. But a large gap exists between most research endeavors and successful commercial marketing of research products. Often, commercialization is an afterthought for researchers, occurring only when they realize that, unless their products attract customers, they will soon have to abandon their efforts. Few institutes address marketing challenges early in the research cycle, and seldom are research projects willingly abandoned because of marketing risk.

Well-managed and technically strong research institutes can provide an important component of the institutional framework for the development of a modern biotechnology industry in Russia. This industry will most likely rely

heavily on medium-size firms, particularly those firms operating within research institutes. Many individual entrepreneurs have attempted to spin technologies out of institutes and develop market niches on their own. But in the absence of a supporting technical and administrative infrastructure, they have often encountered difficulties quickly. In contrast, an optimistic report on vaccine-development research at biotechnology institutes is presented in Appendix O.

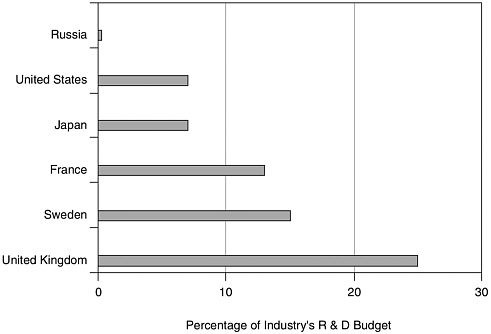

At the other extreme, few large pharmaceutical companies are ready to invest in somewhat risky biotechnology activities, nor do they have the technical where-withal to compete in frontier areas because of the risk represented by financial arrears. Figure 4.1 underscores the reluctance of Russian industry to support research on pharmaceuticals of any type.

An example of an institute that is finding a way to continue its research is Biokhimmash, which has specialized in designing production processes for a variety of biology-based products. Its 200 specialists work on a variety of products such as: (1) new drugs based on plant and animal cell cultures; (2) plant growth stimulators; and (3) veterinary medicines. During the Soviet era, Biokhimmash designed specialty production equipment for biodefense facilities. The institute is now part of Elevar, a construction-oriented company that has very profitably built food processing plants, breweries, and other facilities related to the strengths

FIGURE 4.1 Pharmaceutical share of industrial R&D. SOURCE: Science and Engineering Indicators, National Science Foundation (2004).

|

BOX 4.2

SOURCE: Natsionalnie Biotechnologii (2004). |

and interests of Biokhimmash. Elevar is prepared to use construction profits to support research at the institute, which over time should produce breakthroughs of commercial significance (Biokhimmash, 2003:6).

A second example of institute scientists finding a market niche is the production of insulin by the firm Natsionalnie Biotekhnologii. With Gazprom acting as the principal investor, this firm made the journey to the marketplace from 1996-2002, at a cost of $9.3 million, as shown in Box 4.2.

A handful of other health-related biotechnology investors are active in Russia. For example, Medical Technology Holding is a daughter company of the huge conglomerate Sistema. It has an impressive array of financial sponsors and intends to engage in full-cycle drug production, from research and substance synthesis to production and distribution of the final products. It began with diagnostic kits for viral hepatitis B and HIV, hormones, and markers; currently it is expanding into other high-tech areas. The company has its roots in the scientific capabilities of the Gabrichevskii Scientific-Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology.

In agriculture, the firm NARVAC was established on the premises of the Ivanovskii Scientific-Research Institute of Virology. It produces a variety of animal medications and food supplements. It is funded by a few individual investors, and the forecasts for commercial success are positive. Other firms in a number of cities are also targeting the agriculture sector as a consumer of new biotechnology products, but few have the modern facilities that are available at NARVAC.

It will be difficult, but important, to develop a substantial domestic bio-

technology industry that initially will serve the markets of Russia, the former Soviet states, and more broadly, the world.

DEVELOPMENT OF AN INTERNATIONALLY COMPETITIVE BIOTECHNOLOGY SECTOR

The committee underscores the importance of the Russian government and its international partners in the development of an internationally competitive pharmaceutical/biotechnology sector that can assist in global efforts to combat infectious diseases in Russia and abroad. To this end, Russia needs a strong innovation system from basic molecular biology through applied research and development, intellectual property and regulatory systems, scale-up and production capabilities, and commercial manufacturing, marketing and product distribution systems.

The Russian government recognizes that there is a clear need for stronger high-tech venture capital institutions to support many industrial sectors. The government has invested a few million dollars into several quasi-public institutions and has plans to expand these efforts. There has been limited success but little, if any, in the biotechnology field. In any case, this responsibility must be assumed by the private sector as soon as possible.

As already discussed, producing biotechnology items for the Russian market is not a simple task, even for the most experienced business entrepreneurs. Manufacturing products in Russia for export will be even more difficult. In addition to the complexities unique to biotechnology from clinical trials, to patent uncertainties, to potential military applications of civilian products, many problems hamper all types of businesses in the country. They include difficulties in finding secure facilities, the large number of repetitive inspections of premises and their contents, and the need for entrepreneurs to constantly search for financing in a country where commercial banks are accustomed to repayments of loans within six months. Inconsistent tax policies, intellectual property rights that do not reward scientific success and are rarely enforced, and complicated procedures for licensing facilities and approving products also inhibit commercial activity in Russia (see Appendix P for a key regulation concerning licensing). Finally, of special concern in the health sector is the perception of unfairness and lack of transparency associated with the procurement of drugs and medical devices and other types of fund transfers at the federal and regional levels.

Thus, the committee recommends that the Russian government intensify its efforts to develop a business environment that encourages investment in biotechnology activities. Even in the most favorable environments there are high rates of failure among new biotechnology firms and among new production processes established within existing firms. Therefore, rewards to investors for success should be substantial. Also, the government should recognize that many

large enterprises owned or controlled by the government but on the path to privatization will have difficulty finding resources for updating facilities and for improving management and marketing practices to compete effectively. In some cases, government cost-sharing with such enterprises may be warranted during a transition period.

The committee also recommends that the Russian government promote investment in biotechnology niches that are particularly well suited for activities based in Russia. The manufacture of many types of pharmaceuticals and related products will remain beyond the competitive reach of Russian firms for the foreseeable future. However, there surely are market niches for Russian firms that have not been fully exploited.

One means of promoting investment is to support local production of selected items that are currently imported. For example, government procurement practices should ensure that high-quality, competitively priced Russian products are given adequate consideration when competing with better known imports. While adopting an import substitution policy for the long term might be counter-productive by creating an inward looking mentality among entrepreneurs, during the current economic transition period, it could be very important in starting new firms and in helping to ensure the viability of well-established firms.

A complementary approach is to support Russian manufacturers who are targeting markets in the countries of the former Soviet Union where longtime connections give Russian firms a considerable advantage over foreign firms trying to penetrate these markets. An obvious product for targeted marketing has been diagnostic test kits. Assessments of the needs and imports of these countries should reveal other opportunities as well, such as needs for vaccines and disinfectants.

Another market niche that seems well suited to Russian capabilities is the identification and testing of new natural antibiotic products, given the increasing reluctance of Western pharmaceutical firms to vigorously seek new classes of antibiotics. Russia has not been adequately explored for its microbial flora. The country may have novel micro-organisms in its vast territories.

In all of these areas, government officials and Russian researchers can play important supporting roles for private sector investors. By emphasizing quality control programs that encourage Russian manufacturers to adhere to international standards, the government could help Russian consumers gain confidence in products made in Russia.

In sum, the Russian government and the private sector face many challenges in the biotechnology sector. Special steps by the government are needed to support the emergence of a vibrant and sustainable base of biotechnology firms, and particularly those linked to research institutes, that will in time become internationally competitive. An optimistic approach is set forth in Box 4.3.

|

BOX 4.3 “The optimal direction to advance the biotechnology industry is to prioritize the development of those aspects that are able to quickly become profitable and thereby attractive for private investors. Examples are cattle feeds and pet foods. Such activities could collectively become the ‘locomotive’ pulling the industry as a whole. This is possible because technologically and procedurally the industry is rather uniform, which allows human resources, skill sets, equipment, and procedures to ‘spill over’ from one branch of industry into another, first into those aspects of biotechnology whose products are sold to nongovernmental entities, particularly to individuals and for-profit companies.” SOURCE: Russian expert in agricultural biotechnology (October 2004). |