6

Reshaping U.S.-Russian Cooperation in the Biological Sciences and Biotechnology

Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, a large number of U.S. and Russian organizations have actively promoted bilateral cooperation in the biological sciences and in biotechnology. Most bilateral activities have relied on the U.S. and Russian governments as funders and/or facilitators. Some programs have been oriented toward improving public health, agriculture, environmental protection, and biodefense in Russia and in the United States. Other programs have been directed toward the support of basic research. Most projects have been implemented by government organizations and by elite research and educational institutions in the two countries. In almost all cases, field and laboratory activities have been conducted in Russia with occasional visits by Russian specialists to the United States. Much of the funding for the Russian side, as well as for the U.S. side, has been obtained by the U.S. partners (see Appendix Q, which briefly describes some of the cooperative programs).

The U.S. government had until recently been Russia’s most active international partner in promoting research related to infectious diseases. But recently, the World Bank and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria launched efforts in Russia directed at controlling HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis that are much larger than any U.S. initiatives. Other Western governments are also expanding programs directed at infectious diseases in Russia.

Thus, U.S.-Russian cooperation should be considered within the broader multilateral framework. In addition to the aforementioned international programs, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization are playing increasingly active roles, both in providing assessments of disease incidence and trends, and in helping to coordinate the efforts of many govern-

ments. In particular, the WHO has for many years encouraged programs related to the control of infectious diseases and has established a number of infectious disease “collaborating centers” in Russia. The WHO will presumably continue to expand these efforts in the future.

EXPANSION OF BILATERAL COOPERATION

In the early 1990s, the U.S. and other Western governments began to support basic research in Russia, including research in the biological sciences. Several U.S. agencies such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the Office of Naval Research were increasingly concerned that much of the world-class basic research capability of Russia would be lost because of the sharp decline in funding for science in the country.

Of special concern was the significant loss of talent accompanying the decline in Russian government support for research. As discussed in Chapter 5, this loss of talent has been primarily an internal movement of well-trained specialists away from science careers to the commercial sector in Russia. There has been a less dramatic, but nevertheless important, migration from Russian research laboratories to research centers in other countries.

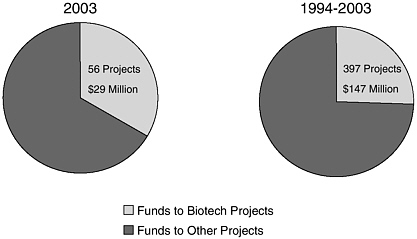

Starting in 1994, the U.S. government initiated several nonproliferation programs that involved cooperative biological research activities. The programs were intended to help ensure that Russian expertise in biology and related fields relevant to weapons would not be transferred deliberately or inadvertently to countries or groups with intentions hostile to U.S. interests. More recently, related nonproliferation programs initiated by the U.S. government have improved safety and security procedures at Russian facilities where strains of dangerous pathogens are stored. These programs also have upgraded facilities for breeding research-quality rodents and for toxicological experiments with rodents and other small animals. Now refurbishing research and manufacturing facilities is underway so that they meet requirements for Good Laboratory Practices and Good Manufacturing Practices as called for by recently promulgated Russian regulations. In addition, biotechnology and the life sciences are clearly a priority area of interest to the International Science and Technology Center in Moscow (ISTC), an international program, which is sponsored by the U.S. and several other governments (see Figure 6.1).

The rapid spread of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in Russia has attracted considerable attention from the U.S. government, resulting in funding provided primarily by the U.S. Agency for International Development, which has a health, and not a nonproliferation, mandate (see Box 6.1). To address a number of other diseases as well, six U.S. departments have sizable programs to redirect former weapons expertise to public health, agriculture, and environmental problems within the framework of nonproliferation. The severe acute respiratory syndrome

FIGURE 6.1 Projects funded by ISTC in Biotechnology and Life Sciences. SOURCE: ISTC Annual Report (2004).

(SARS) outbreak in 2003 made the two governments even more aware of the importance of cooperation in combating infectious diseases through both multilateral and bilateral channels (see Appendix R for a description of programs of special interest to Russia’s Ministry of Health and Social Development).

In the non-governmental sector, several U.S. foundations, particularly the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Vishnevskaya-Rostropovich Foundation, have supported Russian biology researchers and institutions that contribute to world science, disease eradication in Russia, and higher education programs (see Box 6.2). In the commercial sector, a few U.S. pharmaceutical companies have established modest commercial relationships with emerging private sector firms and well-known research institutes. Some U.S. companies are investigating clinical trials of new drugs in Russia. However, investments by the private sector, particularly by U.S. industry, in Russian activities relevant to infectious diseases have been quite limited.

Overall, an impressive array of hundreds of bilateral projects in microbiology, virology, and other fields related to infectious diseases have been conducted over the past decade. The U.S. government currently budgets about $40 million annually for bilateral biological programs, with most of the funds provided for nonproliferation programs. As for industrial activities involving the biological sciences and biotechnology—such as the development and production of vaccines, drugs, and diagnostic devices and the introduction of genetically modified organisms—cooperative efforts have been limited, with U.S. private sector investors uncertain of the risks and skeptical of the rewards from financial involvement in Russia.

|

BOX 6.1 Tuberculosis Prevention and Control

SOURCE: USAID (2003). HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention

SOURCE: USAID (2003). Additional programs

SOURCE: Ministry of Health (2003). |

|

BOX 6.2 The Russian Federation health authorities consider the Children’s Vaccination Initiative of the U.S.-based Vishnevskaya-Rostropovich Foundation a successful model for entering into international partnerships in the Russian public health domain. By focusing on the prevention of viral hepatitis B, the Foundation has demonstrated that it recognizes a major obstacle in the area of health that Russia now faces and has identified creative strategies for overcoming those obstacles. In the territories where adults and youth have been immunized by the Foundation, hepatitis B incidence rates have been reduced by 40–62%. SOURCE: Ministry of Health (2003). |

|

BOX 6.3 In 2002, the CDC invited a young Russian specialist who had received a grant from the ISTC to participate in a training program on modern methods of RT-PCR analysis of sera samples. She applied for an American visa in March 2003 and traveled to Moscow for the required interview at the Embassy. Two months later, she was informed that her patronymic and first names had been switched in the document; and she started the process anew. In November, her ISTC grant expired, and she gave up. Then in February 2004, she unexpectedly was granted a visa. She immediately left for the United States since the validity of the visa could not be extended, even though there was no time to arrange for her to take along SERA samples [needed to maximize the benefits from her collaboration]. SOURCE: Russian research manager (October 2004). |

Overshadowing these activities has been a stubborn legacy of mistrust from the Cold War, linked to U.S. allegations of covert biological weapons activities in Russia. This mistrust has permeated all levels of government in both countries, and has to some degree discouraged cooperation that might, on the one hand, expose sensitive information or, on the other hand, engender unwarranted concern about the intentions of former adversaries. That noted, mistrust over the possible misuse of biological research in the two countries may be gradually subsiding. However, suspicions still circulate among senior officials in both Moscow and Washington about the motivations of the other side for participating in cooperative programs. They sometimes allege that the failure of the other side to ensure complete transparency about their programs may be a screen hiding illicit activities. Unfortunately, mistrust has adversely affected bioengagement programs in many ways, including delaying visa issuances as illustrated in Box 6.3.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STRENGTHENING COOPERATIVE ACTIVITIES

Given the extensive financial and human resources already being devoted by the governments of the United States and Russia to bilateral efforts that address infectious diseases of global concern, the committee recommends three initiatives to improve the effectiveness of cooperation in bioscience and biotechnology to achieve both U.S. and Russian goals. The first initiative is of crucial importance and should be the centerpiece of a stronger, more sustainable, and more beneficial relationship between the two countries.

The U.S. and Russian governments should establish a bilateral U.S.– Russian intergovernmental commission on the prevention and control of infectious diseases. The commission would emphasize cooperative programs that address infectious diseases of global significance, and particularly diseases of special importance in Eurasia. The U.S.-Japan program, begun in 1965, could serve as a model for the commission. Subgroups of the commission might be established to consider the following topics: (1) epidemiology and surveillance of emerging human and animal diseases; (2) laboratory services, including detection, diagnosis, identification, and reference systems; (3) information systems and technologies; (4) biosafety and biosecurity; (5) advanced training; and (6) promotion of scientist-to-scientist contacts. Initially, financing of the activities that the commission endorses would have to come largely from the U.S. government. But a near-term goal should be for each side to cover its own costs during meetings and at the bench. An early task for the commission would be to consider recommendations presented in this report and the contributions of existing bilateral cooperative efforts in implementing the recommendations.

Once the work of the commission is under way, it may be desirable to identify diseases and research areas of priority concern. Panels of experts could then consider recent scientific findings and their relevance to the control of infectious diseases and to future research agendas. Further, annual scientific conferences could be organized. International organizations involving specialists from other countries and occasional workshops could also address approaches to facilitating cooperation. An important aspect of the commission’s work would be to involve in its deliberations leading scientists as well as government administrators with budgetary responsibility who are in the position to reduce impediments to cooperation.

Finally, the U.S.-Japan program has been under way in this field for several decades. The program, jointly supported by both governments and involving multiple small, focused subgroups of experts has been helpful to both governments, especially in the area of infectious disease. The joint committee selects diseases and related topics based on their common relevance to public health in Japan and the United States or globally. The program’s work has led to a better understanding of diseases and an improved capacity to prevent or treat them. In addition, the program provides an excellent opportunity for Japanese and U.S. scientists to collaborate and communicate with colleagues and build research relationships around the globe. A careful examination of how it operates could provide useful guidance in structuring a U.S.-Russian analog.

A second recommendation is to complete the integration of former Soviet biodefense facilities no longer involved in defense activities into the civilian research and production infrastructure of Russia. During the Soviet era, many biological research and production organizations participated in programs sponsored by the Ministry of Defense, in addition to research and production conducted by the ministry itself. The largest organization supporting bioweapons

programs was the USSR Ministry of Medical and Microbiological Industry. Its several dozen facilities employed tens of thousands of technical personnel. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these facilities (now affiliated with Biopreparat), along with many other biology-oriented facilities that had been dependent to a lesser extent on defense orders, encountered difficult economic conditions. Support from the Ministry of Defense declined dramatically. At most institutions that had been dependent on defense orders, such support was terminated completely.

While many other research and production facilities supported defense activities, almost all had civilian missions as well. Thus, during the 1990s the heavily-defense-oriented Biopreparat facilities presented the greatest challenge in bringing former defense scientists into mainstream civilian activities. Therefore, they are discussed in greater detail here.

Since 1991, almost all Biopreparat facilities have lost large portions of their personnel and have greatly slowed hiring of new technical personnel due to diminished government funding. In response, these facilities have turned to civilian-oriented research activities funded primarily by foreign sources. The manufacture of relatively simple products that can be sold in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union has also supplemented income and sustained a reduced level of operations. Yet they have had difficulty joining the Russian civilian infrastructure due to the hesitancy of civilian ministries to assume responsibility for their activities, a lack of historical ties with traditionally open institutes, and security concerns about details of past activities.

|

BOX 6.4

SOURCE: U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (October 2003). |

|

BOX 6.5 A team of Agricultural Research Service scientists and Russian researchers from the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk have developed bacteriocins, natural proteins produced by competing non-pathogenic bacteria, that destroy Campylobacter in the intestines of farmed birds, dramatically eliminating pathogens. Laboratory tests show that treated birds have Campylobacter populations millions or even billions of times lower than untreated ones. Food-borne bacterial infections, such as those caused by Campylobacter, are responsible for billions of dollars of economic losses in the United States and worldwide. Research results from this project have already resulted in patent applications and a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with Cargill, Inc., and could provide an alternative to antibiotics in both the veterinary and medical fields. SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture (December 2004). |

These Biopreparat facilities, however, have some of the strongest biological research capabilities in the country, particularly in dealing with dangerous pathogens. They have demonstrated, through international programs, that they can contribute significantly to both national and global efforts to combat infectious diseases (see, for example, Boxes 6.4 and 6.5). Thus, it is important that they be recognized as legitimate civilian research institutes and not be considered simply as employers of former bioweapons scientists who receive preferential treatment by foreign funders.

To implement the recommendation of further integrating former biodefense facilities into civilian research, it is important to increase the involvement of Russian specialists who did not participate in defense activities but who have important expertise related to disease prevention and control.

A sharp bifurcation of the Russian scientific community between former defense and non-defense scientists not only inhibits the exchange of information within Russia, but also results in a lack of adequate attention to the proliferation potential of the historically civilian biological research sector. Much research on dangerous pathogens conducted in facilities that were never associated with defense programs is inherently “dual-use,” with potential military or terrorist applications. Young scientists with modern laboratory skills, direct access to biological materials, and strong financial ambitions could present a challenging concern.

The U.S. departments and agencies responsible for implementing nonproliferation programs often attempt to link former weapons researchers with civilian

|

BOX 6.6 “Scientists with many years of experience working with the most dangerous pathogens can certainly create greater problems if they were to decide, or were forced, to use this experience elsewhere, say in countries governed by regimes with questionable track records. Their colleagues who worked at ‘open’ institutes usually have only general knowledge of Group A pathogens. Besides, weapon scientists possess specific skill sets and access to (dangerous) strains of micro-organisms. Both could be sources of potential threats, but in the case of weapon scientists, it is significantly higher to the point of becoming realistic. However, it is regrettable that ISTC requires a pre-determined ratio of weapon scientists for each project. The criterion should be the appraised degree of danger coming from the knowledge base of prospective project participants.” SOURCE: Former Soviet bioweapon scientist (November 2004). |

researchers through subcontracting arrangements, and in some cases they have been quite successful. The basic problem remains, however. The U.S. government continues to focus its nonproliferation efforts on those scientists who had direct experience in the former Soviet defense program for reasons set forth in Box 6.6.

Greater efforts are needed to encourage Western program managers to recognize more fully that in the biological arena, the potential for supporting proliferation and terrorism does not only rest with former weapons scientists.

The third committee recommendation is for U.S. and other Western funders to establish true partnerships in Russia. Although some senior U.S. government officials have made efforts to discontinue the use of the term assistance when considering programs with Russia, the U.S. Congress, and U.S. government departments and agencies, along with the American public, perceive programs that involve transferring U.S. government funds to Russia as “assistance” regardless of the commonality of interests and the benefits to the United States. Additionally, notions of U.S. dominance in determining priorities for cooperation, in designing projects, and in working out the details of program implementation have often accompanied the term assistance. Such an approach does not foster sustainability when U.S. funding for joint programs diminishes. Thus, the adoption of the concept of partnership rather than patronage is long overdue. To this end, two approaches are proposed.

The first suggestion is to increase the role of Russian scientists and science administrators in designing cooperative programs and projects. U.S. financial

support that requires U.S. programmatic control will not result in the best use of Russian resources. Russian organizations are usually more familiar with Russian capabilities than are U.S. organizations, enabling them to assume comparable responsibility for determining the priorities and details of cooperative programs. They are also capable of proposing the details of programs, and taking responsibility for successes and failures. Even though Russian managers find it difficult to estimate the economic benefit that will accrue from projects, or design realistic business plans, Western experts are seldom better equipped to do business in Russia. A genuinely cooperative effort in this area, therefore, is particularly crucial.

It is also important that Russians support cooperative programs with enthusiasm that transcends financial benefits. Once funding of a project terminates, an enthusiastic Russian partner is likely to search for ways to continue the activity or to expand upon it in future efforts. An example of a positive outcome of a cooperative project is set forth in Box 6.7.

At the same time, many examples exist of cooperative projects that were so poorly defined at the outset that results were compromised. Unfortunately, there are still research managers in Russia—and, indeed, throughout the world—whose primary interest is to receive money for projects without adequate interest in the contribution of the projects to scientific or economic advancement. Active American participation in projects is often useful in avoiding such difficulties.

A second, related, approach calls for increased Russian financial contributions to cooperative programs as a key to sustainability and as evidence that the programs reflect Russian national priorities. As an initial step, Western payment of salaries for Russian participants in cooperative programs should be gradually

|

BOX 6.7 In September 2004, the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC-International) awarded full accreditation to the SPF Animal Breeding Facility (ABF) of the Branch Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino. Achievement of AAALAC accreditation is a key element of the ABF’s business plan, developed one year ago (2003) through support from the BioIndustry Initiative, and will contribute to the development and sustainability of the ABF. Some of the benefits of AAALAC accreditation include: international recognition; inclusion in the AAALAC Directory and other publications; and access to new markets and clients. SOURCE: BioIndustry Initative Newsletter, Department of State, Volume One (2004). |

decreased and eventually phased out. In the long run, paying salaries is clearly a Russian responsibility. Western financial contributions could be directed more toward supporting institutional infrastructure needed for effective cooperation. Covering the costs of selected modern equipment and supplies and the costs of modern communications networks is increasingly important.

U.S. projects implemented through the ISTC highlight this issue. ISTC’s approach favors support for salaries over support for non-salary items such as equipment, typically awarding less than 50 percent of the total amount to non-salary items in a given project. This is based on the belief that the provision of salary support is the most important factor in reducing incentives for the proliferation of expertise. This short-term argument is important, but it needs to be balanced against the longer-term viability of Russian institutes to continue operations after completion of individual projects. Whether or not there is external financing, the Russian government is usually compelled to provide at least minimal support for salaries whereas financing large equipment purchases is considered optional. As a result ISTC’s best investment in many cases may be to spend 60 to 70 percent of project funds on equipment that will help sustain the research groups into the future. This approach has been successfully integrated into a related Department of State program, the BioIndustry Initiative. These and other shifts in the sharing of responsibility at the project level can often contribute to fostering genuine partnerships as well as helping to ensure the sustainability of cooperative activities.

Collectively, the recommendations in this report, and particularly those in this chapter, should help restore Russia’s capacity to join with the United States and the broader international community in leading an expanded global effort to control infectious diseases. The proposed bilateral intergovernmental commission can play a pivotal role to this end.