5

Implementation

Numerous efforts have been made during the last 10 years to improve the performance of the U.S. air transportation system. Lessons learned from these efforts include the following:

ATC [air traffic control] system development and implementation are chronically delayed, in large part due to shortcomings in analyzing and establishing operational requirements…. Key criteria necessary for more effective ATC system development include stable leadership within the organization, multidisciplinary development teams that cross organizational and public-private boundaries, and a commitment and understanding throughout the organization that ATC system development must be more operationally driven than technology driven…. Modernization efforts [for the National Airspace System] have most often been held up by inadequate understanding of operational and procedural issues, rather than by insufficient technological expertise. (OTA, 1997, pp. 4, 17, 28)

Expanding capacity is not only a function of technology, infrastructure, and design; it is also directly related to how air traffic services are managed and implemented…. While technology and procedures will make [a higher] capacity goal functionally possible, it is continued collaboration between government and the aviation community that will make it happen. (FAA, 2005c, pp. 3, 13)

The proposed schedule for modernization [of the National Airspace System] is too slow to meet projected demands and funding issues are not adequately addressed. (Gore, 1997)

FAA’s organizational culture has been an underlying cause of the agency’s acquisition problems. Its acquisitions were impaired because employees acted in ways that did not reflect a strong commitment to mission focus, accountability, coordination, and adaptability…. In reporting on FAA’s acquisitions, several observers have found that accountability was not well-defined or enforced for decisions on requirements and oversight of contracts—two essential responsibilities in managing acquisitions. (GAO, 1996, pp. 3, 5)

The FAA estimates that it will need $13 billion over the next 7 years to continue its modernization program. However, persistent acquisition problems raise questions about the agency’s ability to field new equipment within cost, schedule, and performance parameters. (GAO, 1996, p. 2)

Appropriations [for the FAA] should be made on a multiyear basis…. This process will promote better overall business planning and provide greater stability for the FAA’s safety, security and public use functions. (Mineta, 1997, p. 35)

The current funding level of FAA’s capital account is not sustainable. This is a result of the combined effects of increased operations costs (salaries) and the fact that modernization projects have suffered so much cost growth that there is little room for new initiatives. This explains why most of FAA’s efforts now focus on keeping things running, or “infrastructure sustainment.” And this is why there is so much discussion about how to finance new air traffic management initiatives. (DOT-IG, 2005, p. 4)

The challenge for the Operational Evolution Plan [to modernize the National Airspace System] is to find ways to continue to develop National Airspace System capacity in collaboration with an aviation community that is hard-pressed to invest in new avionics, test new systems, and commission new runways, and to do so when the agency’s own resources are limited. (FAA, 2005c, p. 3)

The future of U.S. aviation is global. International safety and environmental regulations and ATC standards and

operational procedures are becoming increasingly important to U.S. aviation industry economics. (OTA, 1997, p. 13)

The Integrated Plan has little to say about implementation other than to acknowledge that the IPTs will need to address implementation and transition issues. For example, Chapter 6 of the Integrated Plan, “Approach to Transformation,” contains only a short section on changes in interactions between the government and the private sector, and the discussion is quite general. Much more work is needed to enable successful implementation of NGATS.

The Integrated Plan acknowledges that “the ability to manage effectively across government agencies and fuel government/industry partnerships as the engine of transformation has never been more critical to this country…. Planning and executing a transformational program through partnership requires identifying the key partners, establishing an organizational framework, and implementing processes that support their collaboration” (NGATS JPDO, 2004, p. 22). The assessment committee believes the JPDO’s implementation approach should use organizational collaboration and focus on development of operational products. Successful implementation of NGATS requires an Integrated Plan that does the following:

-

Clearly addresses the needs of the traveling public, shippers, and other system users, which vary with fluctuations in the economy.

-

Establishes a source of stable funding suitable for development, implementation, and operation of NGATS, including capital improvements.

-

Proposes reforms in governance and operational management that assure accountability and limit the effect of traditional external influences. The interests of individual stakeholders should be balanced with the common good in a way that expedites the deployment of optimal technologies and procedures and achieves the primary goal of meeting increased demand.

-

Defines an NGATS that efficiently interfaces with the rest of the global air transportation system.

OUTREACH AND INCENTIVES FOR CHANGE

Most airspace congestion problems in the United States disappeared on 9/11 because of the large decline in commercial air travel. Demand is now recovering to pre-9/11 levels, however, and substantial airspace congestion will recur if modernization efforts do not increase capacity quickly enough. The situation would be exacerbated if the use of small IFR aircraft for intercity travel increases substantially, as the JPDO projects.

The JPDO and the Integrated Plan should clearly and convincingly define the problems that the air transportation system faces and how the changes proposed by the Integrated Plan will solve those problems. Because of the divergent self-interests of different members of the community, reaching consensus will require consistently strong, high-level leadership.

One of the most difficult implementation challenges will be motivating stakeholders to accept change that may lead to an uncertain future in terms of the costs that each stakeholder must bear and the benefits that will accrue. This will be especially difficult where stakeholders are asked to look past their self-interest to improve the air transportation system in ways that primarily benefit others. In some cases, the government can simply mandate change and require industry and other stakeholders to comply, but such an approach is not always appropriate, helpful, or even possible. Economic incentives can be effective and should be considered, though they are often difficult to implement equitably. Even within the federal government, it is often difficult to get action unless a situation is in crisis, yet the goal of the JPDO is to avoid an air transportation crisis rather than wait for one to act as the engine for change. As part of the JPDO’s outreach effort, it is working with state aviation organizations and FAA staff involved with the FAA’s Operational Evolution Plan.

The Integrated Plan states on page 24 that the Senior Policy Committee and JPDO “must create a new model of collaboration throughout government and industry.” Currently, Europe seems to be advancing faster than the United States in many areas covered by the Integrated Plan. Factors contributing to European success include the following:

-

The Europeans recognize the traveling public as the primary customer for the system.

-

A powerful champion (a former vice president of the European Commission) has supported changes to the current system.

-

Europe has been much more willing to mandate some changes than the United States. For example, despite having comparably complex airspace system, Europe implemented reduced vertical separation minima from 2,000 feet to 1,000 feet long before these changes were implemented in the United States.

-

Government-industry cooperation has been more effective than in the United States, in part because it is so difficult for U.S. airlines and other important stakeholders to reach consensus on key issues. Moving forward will be very difficult in the United States without a process that (1) fairly balances the need to create an air transportation system that can meet future demand while avoiding undue hardship for any particular element of the air transportation system and (2) ensures that changes endorsed by a majority of the U.S. air transportation community acting in the national interest cannot be thwarted by the opposition of a vocal minority acting out of self-interest without due regard for the national interest.

-

European efforts to improve their transportation system have not tried to do everything for everybody—an approach that is facilitated by (1) the relatively small size of the business aviation community in Europe and (2) the virtual absence of general aviation and recreational aviation activities.

The Master IPT should identify policy and research decisions that the JPDO will need to investigate in coordination with the policy office of the FAA and other agencies.

SYSTEMS INTEGRATION AND PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Neither the Senior Policy Committee nor the Master IPT will effectively substitute for or diminish the importance of having a competent systems integration capability directed by a strong, fully involved program manager to create and carry out NGATS development and implementation. The JPDO’s scope makes systems integration a difficult challenge—a challenge that is exacerbated by the current IPT organization, in which the IPTs (1) are not aligned with functional requirements and (2) are headed by five different agencies. Effective systems integration requires that the program manager lead the systems integration organization in defining system goals and the path toward implementation. The capabilities of the Master IPT, which has been designated as the JPDO’s systems integrator, must be substantially enhanced to accomplish the above.

The Master IPT should establish an explicit strategy for the use of a shared modeling and simulation capability by all IPTs so that their results can be tested within the overall operational concepts and system architecture using common assumptions and common goals. This modeling and simulation capability should be used in a cost-effective manner, starting with high-level assessments that evolve to later support high-fidelity, detailed assessments over a broad scope.

The systems integration process should also ensure that safety, security, and human factors are considered from the beginning by each of the operational IPTs, to ensure these important factors are considered throughout the development of new technologies, systems, and procedures. Human factors planning during the development of operational concepts, regulations, and system architecture should include consideration of the role of humans and requirements related to personnel selection, training, and information and control.

CERTIFICATION

As the NGATS operational concepts and system definition are developed, certification requirements for aircraft, ground systems, procedures, pilots, and other system operators must be contemporaneously identified to ensure that implementation is not unduly delayed. The JPDO should explicitly incorporate certification requirements into the Integrated Plan and the plans of the IPTs in a timely manner. The JPDO should also support efforts to foster a systems-oriented approach to certification and other efforts to reduce the time and cost required for certification of new equipment and procedures.1

RESOURCES

Funding the development and implementation of NGATS is a major challenge for the FAA and the aviation community as a whole. One measure of the near-term success of the JPDO will be the extent to which the funding and staff allocated by each federal department and agency involved in the JPDO are consistent with JPDO efforts to implement NGATS. For example, some of the proposed reductions in NASA’s aeronautics budget, especially with regard to environmental research, are not consistent with the JPDO’s research goals and would threaten the ability of the JPDO to develop NGATS as described in the Integrated Plan.

Successful implementation of the NGATS vision, goals, and concepts of operations requires the following:

-

a source of stable funding

-

broad support by air transportation system stakeholders to build the public support needed to generate and sustain congressional support for aligning the federal budget with the Integrated Plan and for making other necessary changes

-

an acquisition and implementation plan that is consistent with (1) the ability of all users of the air transportation system to provide revenue and (2) whatever additional funding federal and state governments may choose to provide in recognition of the contribution that the air transportation system makes to national and local economies and public well-being

The current version of the Integrated Plan does not describe the anticipated annual cost of carrying out NGATS research and development activities, because detailed plans are still being prepared by the IPTs. The cost of developing, implementing, and operating NGATS is important because the total costs will be quite substantial, and government and industry resources are expected to be scarce. This is especially true for the airline industry, which is the primary source of revenue and taxes that fund the air transportation system. Operation, maintenance, and modernization of the National Airspace System are funded primarily by the Airport and Airway Trust Fund and, to a lesser extent, by general appropriations from the federal budget. Industry also

|

1 |

Certification issues related to modernization of the air transportation system are addressed in greater detail in the final report of RTCA Task Force 4, issued February 1999 by the RTCA Certification Task Force. Available online at <www.rtca.org/doclist.asp>. |

invests heavily in aeronautics research, and the FAA has authorized many airports to collect a passenger facility charge of up to $4.50 per departing passenger to help fund local airport improvements. Nevertheless, the burden of funding development and implementation of NGATS will likely fall primarily on the Airport and Airway Trust Fund and whatever general appropriations are made available for NGATS activities by the FAA, NASA, and other federal agencies.

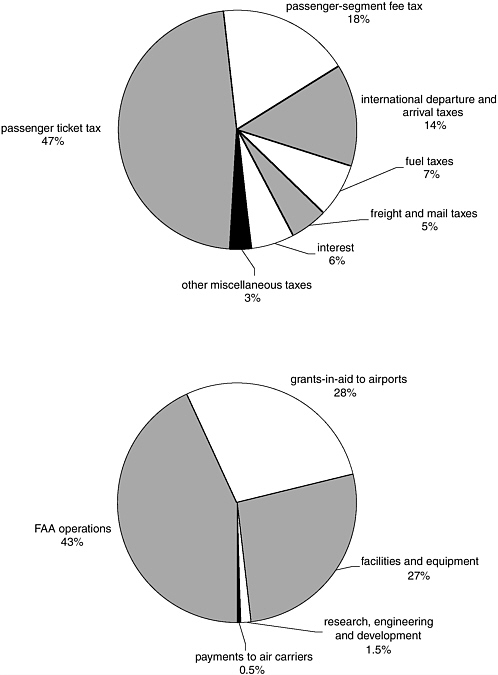

The Trust Fund’s single largest source of income is a 7.5 percent tax on airline tickets (see Figure 5-1), so Trust Fund revenue is closely tied to average ticket price and airline

FIGURE 5-1 Airport and Airway Trust Fund: income (top) and expenditures (bottom). In FY 2004, income totaled $9.7 billion and expenditures totaled $10.4 billion. SOURCES: OMB, 2005; DOT-IG, 2005.

TABLE 5-1 Trust Fund Income and FAA Operational Expenses per IFR Operation, FY 2003 and 2004

|

|

FY 2003 |

FY 2004 |

Change (%) |

|

Number of IFR operations |

17,041,146 |

17,975,226 |

5.5 |

|

Total Trust Fund income |

$9,372,000,000 |

$9,687,000,000 |

3.4 |

|

Trust Fund income per operation |

$550 |

$539 |

−2.0 |

|

FAA operational expenses (budget authority) |

$7,023,000,000 |

$7,479,000,000 |

6.5 |

|

Cost per operation (budget authority) |

$412 |

$416 |

1.0 |

|

Cost of IFR operations (actual outlays) |

$7,144,000,000 |

$7,186,000,000 |

0.6 |

|

Cost per operation (actual outlays) |

$419 |

$400 |

−4.6 |

|

Total FAA budget authority |

$13,540,000,000 |

$14,109,000,000 |

4.2 |

|

Cost per IFR operation (total FAA budget) |

$795 |

$785 |

−1.2 |

|

Total FAA outlays |

$12,560,000,000 |

$12,835,000,000 |

2.2 |

|

Cost per IFR operation (total FAA outlays) |

$737 |

$714 |

−3.1 |

|

Trust Fund expenditures (outlays) |

$9,618,000,000 |

$10,415,000,000 |

8.3 |

|

Trust Fund expenditures per operation |

$564 |

$579 |

2.7 |

|

SOURCES: OMB, 2004, 2005; FAA, 2005d. |

|||

revenue. In recent years, however, the airline industry has lost much of its economic vitality as intense competition from low-cost airlines dramatically reduced average airfares and curtailed airline income and profitability. During 2004, U.S. commercial airlines experienced an 11 percent growth in demand (in terms of revenue passenger miles), and total demand (along with load factors) exceeded pre-9/11 levels by 3 percent. Nonetheless, during 2004 U.S. airlines as a whole experienced operating and net losses of $3 billion and $6 billion, respectively. Many major carriers remain at the brink of bankruptcy, are in bankruptcy, or recently emerged from bankruptcy (FAA, 2005b).

Early in FY 2004, the FAA was reorganized as a single, performance-based organization. Because of reduced ticket prices, Trust Fund income per IFR operation in 2004 was 2 percent less than in 2003. Total income increased, however, because the total number of IFR operations increased by 5 percent. In addition, the cost of FAA operations per IFR flight increased only slightly in 2004 (by 1 percent, if cost is assumed to equal the allocated budget for FAA operations), or it decreased by 5 percent (if cost is assumed to equal actual outlays) (see Table 5-1).

The Trust Fund had a balance of $12.4 billion at the beginning of FY 2004. A continuation of (1) current funding practices by the federal government and (2) current pricing policies and economic conditions in the airline industry is almost certain to deplete the Trust Fund. The balance could be reduced to $10.9 billion by the end of FY 2006 (OMB, 2005) and to $4.4 billion by the end of FY 2009 (FAA, 2005a), and the Trust Fund could be facing a cumulative deficit of more than $12 billion by 2025 (Cordle and Poole, 2005). Given ongoing concerns about the size of the federal budget deficit, it is problematic to assume that general tax revenues will be readily available to pay for whatever expenses the Trust Fund cannot cover. In addition, increased appropriations (or higher aviation tax rates, or other sources of funding) will be needed to preserve the Trust Fund to the extent that the substantial cost of developing and implementing NGATS exceeds currently planned budgets for modernization of the National Airspace System.

On the other hand, the Trust Fund’s financial situation will be improved to the extent that trust fund income exceeds expectations (e.g., as a result of increases in the quantity of air travel and/or average ticket prices). In any case, Trust Fund balances for future years cannot be predicted with confidence because of the many uncertainties that affect Trust Fund income and expenditures. In particular, the aviation taxes that sustain the Trust Fund will expire in September 2007. Even if one assumes that the taxes will be renewed in FY 2008 by the next FAA authorization act, it is impossible to know what the future tax rates will be. For example, the tax rate on airline tickets has been 7.5 percent since FY 2000, but for most of the 1990s the rate was 10 percent, and during the 1980s it varied from 5 percent to 8 percent. Since the ticket tax accounts for about one-half of Trust Fund income, the accuracy of projected Trust Fund balances beyond 2007 is heavily dependent on the accuracy of current assumptions about future aviation tax rates.

The financial picture is further complicated by the federal system of budgeting, because the uncertainty of annual appropriations makes it more difficult to develop and carry through on long-term plans and commitments.

Long-term projections of Trust Fund balances also presume that the means of funding FAA operations will remain essentially unchanged, despite ongoing efforts by the FAA and others to substantially change the FAA funding model. The assessment committee did not evaluate funding mechanisms and takes no position on the appropriateness of various options, except to note that the implementation of NGATS will require a reliable source of adequate funding,

and this challenge will obviously be mitigated if costs can be reduced. The FAA expects ongoing business problems in the airline industry to create additional pressure on the FAA to “improve productivity, manage costs, and cut back on services that provide little value” because “near-term funding is threatened by the decreasing balance of the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, and trends within the aviation industry strongly suggest diminishing contributions to the Fund in the years ahead”; in addition, the FAA “must address both badly needed modernization and one-for-one replacement of experienced retirees at a time when the workload is growing more complex.” To succeed, the FAA believes that stakeholders “will have to collaborate in meaningful, forward-thinking ways, setting aside narrow interests and focusing on a future that best serves all” (FAA, 2005d, p. 51). The assessment committee concurs, with the caveat that changes in governance and operational management of the National Airspace System may be needed to limit the ability of individual, self-interested stakeholders to slow or put a stop to proposed changes in the sources of funding or in the design or operation of the National Airspace System. The assessment committee would endorse efforts to cut costs, for example, through closure of nonessential activities and facilities, perhaps using a process similar to the Department of Defense Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process.2 In addition, incorporating cost data into the planning process would help prioritize requirements and improve the focus of IPT research and objectives.

Finding 5-1. JPDO Resources. Sufficient resources are not currently available to the JPDO for it to successfully define the Next Generation Air Transportation System and an appropriate implementation plan.

Finding 5-2. Funding Stability. Development, implementation, and operation of the Next Generation Air Transportation System require a plan to assure adequate, stable funding.

Recommendation 5-1. Funding Allocation. The members of the Senior Policy Committee should ensure that the federal agencies they direct or represent allocate funding and staff to (1) provide the JPDO with the resources it needs to define the Next Generation Air Transportation System and draw up an appropriate implementation plan and (2) ensure departmental and agency research in civil aeronautics is consistent with JPDO plans to enable and implement new operational concepts. Reductions in NASA’s aeronautics program that would significantly curtail research necessary to achieve goals related to environmental protection and other core research identified by the JPDO should be avoided and/or corrected.

Recommendation 5-2. Funding Model. The secretary of transportation and the FAA administrator should lead the development of a proposal to adequately fund the development, implementation, and operation of the Next Generation Air Transportation System. This proposal should consider a wide range of options for providing necessary funding, both public and private, and for eliminating unnecessary costs.

Recommendation 5-3. Cost Reductions. The implementation plan for the Next Generation Air Transportation System should explicitly address ways to reduce the cost of system implementation and operation.

REFERENCES

Cordle, V., and R.W. Poole, Jr. 2005. Resolving the Crisis in Air Traffic Control Funding. Policy Study 332. Los Angeles, Calif.: Reason Foundation. Available online at <www.rppi.org/air.html>.

Department of Transportation, Inspector General (DOT-IG). 2005. “Perspectives on the Aviation Trust Fund and Financing the Federal Aviation Administration.” Statement of the Honorable Kenneth M. Mead before the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Subcommittee on Aviation, U.S. House of Representatives. May 4, 2005. CC-2005-033. Washington, D.C.: Department of Transportation. Available online at <www.oig.dot.gov/item.jsp?id=1549>.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). 2005a. Air Traffic Organization Fiscal Year 2005 Business Outlook. Washington, D.C.: FAA.

FAA. 2005b. FAA Aerospace Forecasts, Fiscal Years 2005 to 2016. Washington, D.C.: FAA. Available online at <www.api.faa.gov/forecast05/Forecast_for_2005.htm>.

FAA. 2005c. Operational Evolution Plan, 2005-2015. Version 7.0. Washington, D.C.: FAA. Available online at <www.faa.gov/programs/oep/INDEX.htm>.

FAA. 2005d. Year One, Taking Flight. Air Traffic Organization 2004 Annual Performance Report. Washington, D.C.: FAA. Available online at <www.faa.gov/library/reports/media/APR_year1.pdf>.

General Accounting Office (GAO). 1996. Aviation Acquisition: A Comprehensive Strategy Is Needed for Cultural Change at the FAA. GAO/ RCED-96-159. Washington, D.C.: GAO. Available online at <http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/000/400/477/rc96159.pdf>.

Gore, A. 1997. White House Commission on Aviation Safety and Security, Final Report. “Making air traffic control safer and more efficient.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. Available online at <www.fas.org/irp/threat/212fin~1.html>.

Lizotte, K. 2005. Historical Passenger Ticket Tax, International Departure/Arrival Tax and Cargo Tax Rates, 1970 to Present. Washington, D.C.: FAA. Available online at <http://apo.faa.gov/Trust%20Fund%20Website/AATF_Home.htm>.

Mineta, N. 1997. Avoiding Aviation Gridlock and Reducing the Accident Rate: A Consensus for Change . Final Report of the National Civil Aviation Review Commission. Washington, D.C.: Department of Transportation. Available online at <www.faa.gov/NCARC/instructions.cfm>.

Next Generation Air Transportation System Joint Planning and Development Office (NGATS JPDO). 2004. Next Generation Air Transportation System Integrated Plan. Washington, D.C.: JPDO. Available online at <www.jpdo.aero>.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2004. Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2005—Appendix. Federal Aviation Administration, p. 766ff. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Available online at <www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2005/pdf/appendix/dot.pdf>.

OMB. 2005. Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2006—Appendix. Federal Aviation Administration, p. 785ff. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Available online at <www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2006/pdf/appendix/dot.pdf>.

Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). 1994. Federal Research and Technology for Aviation. OTA–ETI-61O. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Available online at <http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/000/500/598/9410.htm>.