4

Food and Beverage Marketing to Children and Youth

INTRODUCTION

This chapter considers how food and beverage products are developed and marketed to appeal to the preferences of children and youth and to stimulate sales. It provides definitions of certain commonly used marketing terms and approaches; provides an overview of various target markets such as tweens, teens, and ethnic minorities; and offers a description of the marketing research enterprise directed at children and youth. An overview is provided of the marketing environment, including a profile of food and beverage companies and retailers, full serve and quick serve restaurants, and trade associations. It discusses food, beverage, and meal product development, the implications of the evolving purchasing power of American children and youth, and the general marketing strategies, tactics, and messaging used by industry. The chapter also reviews children’s and adolescents’ media use patterns and advertising exposure, and discusses the range of marketing vehicles and venues used by companies to reach them with advertising and marketing messages. A discussion of company and industry guidelines and policies, including self-regulatory programs, health and wellness advisory councils, public–private partnerships, and coalitions concludes the chapter.

To explore this domain, the committee drew from several different types of reviews, reports and materials, including supplementing the peer-reviewed literature with information from industry and marketing sources. Thus, the evidentiary sources cited in this chapter include articles published

in marketing, advertising, or industry trade journals; commissioned papers examining the current and future food and beverage marketing trends affecting children and youth; government, company, and trade organization websites; annual reports of companies;1 foundation or nonprofit organization reports and briefs; popular magazines and books relevant to advertising and marketing; and news releases. Sources also included materials from presentations, testimony, and documents provided during and following the January 2005 public workshop held to consider industry perspectives and activities. To assess the degree to which new food and beverage products have been targeted to children and youth across various product categories, the committee also conducted an analysis of trends in the proliferation of children’s products using ProductScan®, a large commercial database of products (Marketing Intelligence Service, 2005) that has tracked new product introductions in the U.S. marketplace since 1980 (Williams, 2005b).

Because marketing research could enhance understanding on the relationships of marketing strategies to children’s food and beverage consumption patterns and diets and diet-related health outcomes, as well as the design of strategies to improve the healthfulness of messages, several market research firms were contacted for information. Some—The Geppetto Group, The Strottman Group, KidShop/KidzEyes, and Yankelovich Partners—provided child- and youth-specific data for the committee’s consideration and use. Others were unable to provide information, either because of time constraints, economic considerations, or on the basis that the data were proprietary and not intended for public use. A summary of the marketing research information considered by the committee is included in Appendix E, Table E-1.

MARKETING TERMINOLOGY AND APPROACHES

Marketing professionals use a variety of strategies to influence consumer preferences, stimulate consumer demand, promote frequency of purchases, build brand awareness and brand loyalty, encourage potential or existing customers to try new products, and increase sales. From a marketing perspective, businesses engage in a variety of activities that are designed to meet customers’ needs and to create the context where consumers perceive value in exchange for their money. Marketing is defined by the American Marketing Association (AMA) as “an organizational function and a set

of processes for creating, communicating, and delivering value to customers and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit an organization and its stakeholders” (AMA, 2005a). Conducting marketing research is a fundamental activity of the marketing process, providing information that helps identify opportunities and problems, refine strategies, and monitor performance (AMA, 2005a).

The four traditional components of marketing are as follows:

-

Product (e.g., features, quality, quantity, packaging)

-

Place (e.g., location, outlets, distribution points used to reach target markets)

-

Price (e.g., strategy, determinants, levels)

-

Promotion (e.g., advertising, consumer promotion, trade promotion, public relations)

Figure 4-1 shows one approach to a graphic representation of the elements that influence a marketing strategy: defining the target market, determining the marketing mix to meet the needs of that market, and assessing

FIGURE 4-1 Elements of a marketing strategy and its environmental framework.

SOURCE: Based on Boone and Kurtz (1998). From Contemporary Marketing, 9E 9th edition by Boone. ©1998. Reprinted with permission of South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning: www.thomsonrights.com.

the relevant competitive, social-cultural, technological, economic, political-legal, and environmental factors (Boone and Kurtz, 1998).

Branding

A key aim of marketing is product branding—providing a name or symbol that legally identifies a company, a single product, or a product line to differentiate it from other companies or products in the marketplace (Roberts, 2004). Elements of branding strategy may be characterized on several dimensions: (1) brand differentiation, to distinguish one brand from another in the same product line; (2) building brand image (or brand presence) to raise consumers’ awareness about a brand and the competition; (3) developing brand equity (also referred to as brand relevance and brand performance), to build brand familiarity and perceived quality with the intent to meet a customer’s expectations and purchase intent, which is the extent to which a consumer intends to continue purchasing a specific brand; (4) assessing brand momentum (or brand advantage) to determine whether customers think a brand is improving or whether their interest in a specific brand is declining; and (5) building and sustaining brand loyalty (also referred to as brand bonding), which is the degree to which consumers will consistently purchase the same brand within a product category (BrandWeek, 2005; Survey Value, 2005).

In effect, the purpose of branding is to promote product sales by taking a product and identifying it with a lifestyle to which consumers aspire (Roberts, 2004). With food and beverage products, product development can be part of the branding process, as with many prepared entrees, baked goods, savory snacks, confectionery, and carbonated soft drinks (CSDs)2. Nonprocessed foods such as vegetables and fruits are more difficult challenges for brand differentiation, and are generally less promoted than processed food brands. This may be beginning to change, however, as there is a developing trend toward branding produce and promoting innovative features such as new shapes or colors, special varieties (e.g., baby or seedless watermelon, champagne grapes) and ethnic fruits and vegetables that help to build consumer awareness, sales, and profits (Pollack Associates, 2004).

Processed foods are highly branded and lend themselves to major advertising (Gallo, 1999). More than 80 percent of U.S. grocery products

are branded whereas only 19 percent of fruits and vegetables are nationally branded (Harris, 2002). Results from a Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) survey of 800 consumers found that Americans across all demographic groups consider a product’s brand before making a final purchase selection, and consumers will pay a higher price for perceived quality in premium branded products and will go to a different store if a preferred brand is not available (GMA, 2002; Pollack Associates, 2004). Key factors that influenced their brand selection include experience (36 percent indicated that prior family exposure influences brand choice) and peer endorsement (13 percent) (GMA, 2002). Branding has become a normalized part of life for American children and adolescents (Schor, 2004), as marketers seek to develop positive and sustained brand relationships with young consumers and their parents in order to create brand recognition and foster brand loyalty, brand advantage, and brand equity (McDonald’s Corporation, 1996; McNeal, 1999; Moore et al., 2002).

Advertising

Advertising is the most visible form of marketing. It is paid public presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services by a sponsor (Kotler and Armstrong, 2004), intended to bring a product to the attention of consumers through a variety of media channels such as broadcast and cable television, radio, print, billboards, the Internet, or personal contact (Boone and Kurtz, 1998). Marketers recognize its value by itself, and also view it as contributing to the success of other strategies by (1) building brand awareness and brand loyalty among potential consumers, and (2) creating perceived value by persuading consumers that they are getting more than the product itself (e.g., social esteem, peer respect).

Consumer Promotion

Consumer promotion, also called sales promotion, represents the promotional efforts that are designed to have an immediate impact on sales. Consumer promotion includes media and nonmedia marketing communications targeted directly to the consumer that are used for a predetermined and limited time to increase consumer demand, stimulate market demand, or improve product availability. Examples of sales promotion include coupons, discounts and sales, contests, point-of-purchase displays, rebates, and gifts and incentives (Boone and Kurtz, 1998).

Trade Promotion

Trade promotion is a broad category of marketing that targets interme-

diaries, such as grocery stores, convenience stores, and other food retail outlets. Trade promotion strategies include provision of in-store displays, agreements for shelf space and positioning, free merchandise, buy-back allowances,3 and merchandise allowances,4 as well as sales contests to encourage wholesalers or retailers to give unusual attention to selling more of a specific product or lines (Boone and Kurtz, 1998). Companies usually spend as much of their marketing budgets on trade promotion as on expenditures for advertising and all other consumer-oriented sales promotion, combined (Boone and Kurtz, 1998; GMA Forum, 2005).

Market Segmentation and Target Markets

Identifying and reaching unique target markets is important for businesses to promote sales in a competitive marketplace. Target markets may be segmented by demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, income, race or ethnicity), psychographic features (e.g., values, attitudes, beliefs, lifestyles), behavioral patterns (e.g., brand loyalty, usage rates, price sensitivities), and geographic characteristics (e.g., region, population density) (Neal, 2005; QuickMBA, 2004). As the ethnic, racial, and cultural composition of the U.S. population changes and boundaries among groups become less distinct through intermarriage and cultural adaptation, the criteria that marketers have used to target specific groups of consumers may change (Grier and Brumbaugh, 2004).

Companies often alter the types of products and services marketed (marketing mix) for customers in each market segment in order to meet the demand for products and services and to maximize sales. Marketers may change only one element of the marketing mix (e.g., promotional approach), or tailor each element of the marketing mix to a specific population segment—the product and how it is packaged, the pricing strategies, the place(s) or channel(s) through which the product is distributed and made available to consumers in a target market, and the promotional strategies (Neal, 2005; QuickMBA, 2004).

Children and youth represent an important demographic market because they are potential customers, they influence purchases made by parents and households, and they constitute the future adult market (McNeal, 1998; Moore et al., 2002). Table 4-1 summarizes the U.S. Census Bureau

TABLE 4-1 Marketing Categories by Population Sizes

|

Group |

Age Range |

Population Size |

|

Infants and Toddlers |

0–2 years |

|

|

|

Girls |

5,575,564 |

|

|

Boys |

5,841,112 |

|

Children |

3–8 years |

|

|

|

Girls |

11,734,700 |

|

|

Boys |

12,306,607 |

|

Tweensa |

9–12 years |

|

|

|

Girls |

8,159,391 |

|

|

Boys |

8,572,920 |

|

Teensb |

13–19 years |

|

|

|

Girls |

13,758,399 |

|

|

Boys |

14,524,572 |

|

aIn this report, the committee characterized infants and toddlers as under age 2 years, younger children as ages 2–5 years, older children as ages 6–11 years, and teens as ages 12–18 (Chapter 1). These age categories and terms differ slightly from what is described in this chapter. Marketers distinguish the tween market segment from children and teens, defining it as young people who have attitudes and behaviors that are “in between” the ages of 8–12 years or 9–14 years (Siegel et al., 2001; The Intelligence Group/Youth Intelligence, 2005). bThe U.S. Census Bureau defines teens as young people ages 13–19 years. SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau (2000). |

||

age categories that differ from the age categories used in this report (Chapter 1 and Chapter 5) and commonly used by marketers. The Census Bureau age categories include infants and toddlers (ages 0–2 years), younger and older children (ages 3–8 years), tweens (ages 9–12 years), and younger and older teens (ages 13–19 years).

Children and youth under the age of 19 years comprise more than a fourth of the U.S. population. From 1990–2003, this population increased by 14 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001, 2004). Ethnic minorities represent attractive targets for food and beverage marketers due to their size, growth, and purchasing power (Williams, 2005a). Marketers segment target audiences by age, gender, and race/ethnicity to build brand awareness and brand loyalty early in life that will be sustained into adulthood. African American consumers have been targeted by both mainstream and African American-owned marketers, often using very different marketing styles (Williams and Tharp, 2001). Food and beverage companies market to African American family preferences. An analysis of 2004 Nielsen Monitor-Plus data of food and beverage advertising that appeared in African American media showed significant spending by food and beverage companies for high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages.

In six magazines targeted to African Americans (e.g., Jet, Ebony, Black Enterprise, Essence, Vibe, and Savoy), the top three categories advertised were regular CSDs ($1.8 million), cookies and crackers ($1.6 million), and fruit juices and fruit-flavored drinks ($1.5 million). Advertising spending for the top three food and beverage categories on Black Entertainment Television (BET) were regular CSDs ($10.8 million), candy and gum ($8.8 million), and fruit juices and fruit-flavored drinks ($5.3 million) (Williams, 2005a). Magazine Publishers of America estimates that 15 percent of teens ages 12–19 years are African American, and are a major influence on youth culture, spending 6 percent more per month than the average U.S. teen, which is estimated at $428 monthly (MPA, 2004b).

In 2004, the industry advertising and marketing expenditures were estimated at $260.9 million to reach consumers through Hispanic/Latino-oriented broadcast television networks, cable television, and Spanish-language newspapers and magazines (Endicott et al., 2005). Among the food, beverage, and retailer companies, PepsiCo spent $68.5 million, McDonald’s Corporation spent $65.8 million, Wal-Mart Stores spent $55.9 million, Yum! Brands spent $30.8 million, The Coca-Cola Company spent $27.7 million, the Kellogg Company spent $25.2 million, and Wendy’s International spent $20.4 million to advertise brands to reach Hispanic/Latino consumers (Endicott et al., 2005). An example of an ethnically targeted marketing effort to Hispanics/Latinos is PepsiCo’s Frito-Lay™ Flaming Hot Corn Chips advertising campaign (MPA, 2004c).

The Hispanic/Latino teen market is the fastest growing ethnic youth segment in the United States. This market currently represents 4.6 million young consumers, or 20 percent of all U.S. teens. Market researchers forecast that the Hispanic/Latino youth population is expected to grow six times faster than the rest of the teen market by 2020 (MPA, 2004c). Marketers view the Hispanic/Latino youth market as providing a variety of business opportunities across many types of products and services (Valdés, 2000). In 1998, the total annual purchasing power of Hispanic/Latino teens was estimated at $19 billion—4 percent higher than non-Hispanic/Latino teens (MPA, 2004c). This so-called Generation Ñino includes tweens, teens, and young people who are bilingual and bicultural as they retain their Hispanic/Latino identity and navigate comfortably in this culture and American cultures (Valdés, 2000).

Cultural influences among different racial/ethnic groups are also possible. For example, “hip-hop” youth culture originated among African American youth in the inner city, and is now embraced by a generation of African American, white, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian youth (Williams and Tharp, 2001). “Urban culture” is a term used to describe a target market that has a particular lifestyle. Urban culture transcends both racial and ethnic boundaries by bringing together a lifestyle of fashion, attitudes,

street language, and music from all backgrounds (Williams and Tharp, 2001). MTV has been a leading entertainment network partnering with PepsiCo and The Coca-Cola Company to launch advertising campaigns featuring hip-hop culture such as break dancing to market CSDs and urban culture to teens (Holt, 2004; PBS Frontline, 2001).

With respect to economic segmentation, there is some descriptive evidence suggesting that ethnic minorities living in poorer neighborhoods have fewer healthier options and neighborhood restaurants heavily promote less healthful foods (Lewis et al., 2005; Chapter 3). Despite concerns expressed that marketers disproportionately target racial/ethnic minorities with high-calorie, low-nutrient foods and beverages, there is a need for greater empirical evidence to support the claim (Grier, 2005; Samuels et al., 2003). The committee was not able to find available evidence to assess whether market segmentation has been a significant influence on children’s food and beverage product development.

Embedded Marketing Strategies

Embedded marketing strategies blend commercial content with programming or editorial content, or other lifestyle experiences, to add brand exposure and avoid resistance to direct advertising. Product placement, or brand placement, is an embedded marketing technique that refers to the inclusion of a corporate or brand name, product package, signage, or other trademark either visually or verbally in television programs, films, video games, magazines, books, and music, or across a range of these media simultaneously (Babin and Carder, 1996; Nebenzahl and Secunda, 1993; PQMedia, 2005). Product placement is generally arranged in return for a fee payment, although occasionally other quid pro quo accommodations are involved (Balasubramanian, 1994; PQMedia, 2005).

Another form of embedded marketing technique used by marketers is known as viral marketing, representing the “buzz,” “word of mouth,” or “street marketing” that occurs when individuals talk about a product to one another, either in conversations or virtual communication via an electronic platform such as the Internet (Henry, 2003; Holt, 2004; Kaikati and Kaikati, 2004). Viral branding and marketing focus on the paths of public influence, including diffusion of innovation, word of mouth, and public relations (Holt, 2004).

Measured Media and Unmeasured Media

Marketers pay to advertise and promote branded products through a variety of media channels, termed measured and unmeasured media in the marketing literature. Measured media spending refers to the categories that

are tracked by media research companies such as Nielsen, TNSMI/CMR, and Forrester. Commonly tracked measured media spending categories include television (e.g., network, spot, cable, syndicated, Spanish-language network), radio (e.g., network, national spot, local), magazines (e.g., local, Sunday magazine), business publications, newspapers (e.g., local, national), outdoor, the Yellow Pages, and the Internet (Brown et al., 2004, 2005).

Unmeasured media spending refers to the difference between a company’s reported or estimated advertising costs and its measured media spending. Unmeasured media spending includes activities such as sales promotions, coupons, direct mail, catalogs, and special events, and it is not systematically tracked (Brown et al., 2004, 2005). Marketers use a variety of techniques to assess the effects of advertising in measured media on consumers. They measure the cost of advertising or promotion, usually expressed in terms of consumer exposure to advertising messages or “impressions,” representing a message seen by one viewer. Thus, consumers who report that they remember or recall an advertisement have “retained impressions” of the specific advertisement. Marketers also track consumers’ recall, retention, processing of messages, and purchase intent or purchase behavior. A second measure of the impact of an advertisement used by marketers is the increase in sales as a result of the advertising or promotional campaign. Because several factors may influence sales in the marketplace, it may be difficult to isolate the effect of advertising on sales of a particular product during a given time period. Thus, companies and marketers use other measures to guide their decisions, including communications research, an analysis of purchase dynamics (e.g., trial purchase, repeat purchase, frequency of purchase), and tracking consumer awareness and attitudes regarding specific product categories and specific brands (Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services, 2005c).

Once the purchase behavior of the exposed and unexposed groups are evaluated for a pre- and post-period, marketers determine brand penetration (the percentage of households that purchased an advertised product), volume (the average number or weight of an advertised product for every 100 households), dollars spent (the average dollars spent on the advertised product for every 100 households), and the dollar share (the percentage of sales that the advertised brand represents of total category sales) (MPA, 1999).

Marketing Research

Substantial investments have been made in marketing research directed to U.S. children and youth, and this research has grown into a major marketing tool over the past 30 years (Austin and Rich, 2001; McNeal,

1999; Schor, 2004). Its evolution and focus on youth has been rapid. Companies and private marketing research and public relations firms currently conduct marketing research that involves children and adolescents of all ages in the stages of product development, market testing, and the design of messages that are delivered to them (Schor, 2004). Examples of selected marketing research firms and marketing reports that the committee considered through its data-gathering process are listed in Appendix E, Table E-1.

Marketing research firms use a variety of methods, such as convenience surveys, opinion polls, focus groups, participant observation, photography, and ethnographic studies to collect information about their target markets (e.g., age and income of consumers, purchasing power, spending patterns, consumer attitudes and opinions)—including, in some cases, market research focus groups with early- and preschool age children (Austin and Rich, 2001; Buzz Marketing Group, 2004; Friend and Stapylton-Smith, 1999; Nestle, 2002; PBS Frontline, 2001; Peleo-Lazar, 2005; Schor, 2004; Teinowitz and McArthur, 2005; Yankelovich, 2005). Cultural anthropologists and psychologists have become regular resources for marketing research firms to study the culture of children and youth, and to research how children and teens process information and respond to advertising (Montgomery and Pasnik, 1996; Schor, 2004).

Some marketing research is developed for public use but most is proprietary. Public research is conducted primarily by academic institutions and may be financed by public or private funds. Proprietary research is conducted for commercial purposes by private companies, marketing research and public relations firms, or companies that are associated with the marketing industry, and is not publicly available. Appendix E, Table E-1 provides examples of the types of proprietary research focused specifically on the eating habits and lifestyles of children and youth and the companies or marketing research firms that collect and sell these data. Because the majority of nonacademic research conducted by marketing research firms, public relations firms, and companies is proprietary, these data are unavailable to help assess the direct relationship between advertising and sales (Nestle et al., 1998), as well as the impact of advertising and other forms of marketing on children’s and adolescents’ food choices and diet (Swinburn et al., 2004; Chapter 5).

Finding: Marketing research can provide important insights about how marketing techniques might help improve the diets of children and youth. Yet, much of the relevant marketing research on the profile and impact of food and beverage marketing to children and youth is currently unavailable to the public, including for use in designing and targeting efforts to improve the diets of children and youth.

MARKETING ENVIRONMENT

Companies, Retailers, Restaurants, and Trade Associations

Food and Beverage Companies

Two federal government series reports provide estimates of food expenditures in the United States: The Economic Research Service (ERS) Food Expenditure Series published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which provides actual food sales information obtained from total food sales of retail establishments that sell food items, based on food sales in the Bureau of the Census Retail Trade Reports; and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey, which is based on annual household expenditure surveys that measure food purchases of the consuming units or households surveyed (ERS/USDA, 2005a). Food and beverage expenditures have grown at approximately 6.4 percent per year for the past 40 years5 (ERS/USDA, 2004, 2005b). Sales for total U.S. food and beverage consumption were $895.4 billion in 2004 (ERS/USDA, 2005b). The BLS survey reports the distribution of food expenditures for food categories by selected demographic categories. Consumer expenditures for food in 2002 accounted for 13.2 percent of a household’s disposable income, with 7.6 percent spent for foods at home and 5.6 percent for foods acquired away from home (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004; Table 4-2).

Many factors have contributed to the growth of the modern American food industry, including agricultural improvement, new food processing technologies, expanded transportation facilities, and evolving communication systems (Tillotson, 2004). Historically, the growth of the processed-food retail sector in the United States has been important both for supporting economic growth and feeding an evolving, nonagricultural society (Tillotson, 2004).

The majority of the top 25 global food and beverage companies are also leading producers of child- or youth-specific branded food and beverage products (Food Engineering, 2004). These companies include Nestlé S.A., Kraft Foods, Cargill, PepsiCo, The Coca-Cola Company, Cadbury Schweppes, Mars, ConAgra, General Mills, and the Kellogg Company (Williams, 2005b). Worldwide revenues for leading food and beverage companies in 2003 and 2004 are shown in Table 4-3.

TABLE 4-2 Average Annual Expenditures of Households and Percent Distribution of Total Food Expenditures, 2002

TABLE 4-3 Selected Leading Food and Beverage Companies’ Global Revenues, 2003 and 2004

Companies continuously develop new products or reformulate existing products to keep pace with changing consumer tastes and preferences, new technology, and competition. In 2000, a typical supermarket offered an estimated 40,000 products from more than 16,000 food processing companies (Harris, 2002). Selected leading food companies’ top brands, total sales, and marketing media expenditures for these brands in 2004 are shown in Table 4-4.

The beverage industry includes the manufacturers, distributors, and franchise companies engaged in the production and sale of many different product brands, including regular, no-calorie, and low-calorie CSDs; ready-to-drink teas and coffees; bottled waters, fruit juices, and nonjuice fruit drinks; sports and energy drinks; and milk-based beverages (ABA, 2004, 2005a). Over the past several years, there has been a significant expansion of diet, low-fat, low-calorie, and caffeine-free varieties of traditional beverage products (FitchRatings, 2004). In 2003, more than 5,200 new ready-to-drink, nonalcoholic beverages were introduced in the United States (ABA, 2004). In the same year, single-serving bottled water sales increased by 21.5 percent and single-serving sports drink sales increased by 17.9 percent.

In 2003, two companies represented 75 percent of the market share for CSDs—The Coca-Cola Company (44 percent) and PepsiCo (31.8 percent) (Beverage Digest, 2004). The leading beverage brands, companies, and marketing media expenditures in 2004 are shown in Table 4-5.

The food and beverage industry attracts large financial investments based on the expectation of continued growth and profitability (Tillotson, 2004). According to an opinion survey of the 10 leading global food companies, the strategies identified as most likely to help the leading food companies grow over the next 3 years were: (1) innovating and launching new products into developed markets; (2) category expansion such as moving from confectionery to frozen foods; and (3) merger and acquisition activities in developed markets and high-growth potential markets (Business Insights, 2005a).

With respect to healthful products, the prospects were viewed as mixed. The heightened public interest in health and wellness and increased concern about obesity presents certain marketing risks—such as increased costs associated with developing, reformulating, packaging, test marketing, and promoting food and beverage products, as well as uncertainty related to creating and sustaining consumer demand for these new products. However, the public interest and concern also presents potentially profitable marketing opportunities not yet fully explored—food and beverage manufacturers can compete for and expand their market share for healthier food and beverage product categories, be role models for the industry by substantially shifting overall product portfolios toward healthier products, and

TABLE 4-4 Selected Leading Companies’ Top Food Brands, Total Sales, and Marketing Media Expenditures by Category, 2004

|

Brand |

Company Name |

Headquarters |

Total Sales ($ millions) |

Marketing Media Expenditures ($ millions) |

|

Ready-to-Eat Cereals |

|

|||

|

Cheerios |

General Mills |

Minneapolis, MN |

289.7 |

34.5 |

|

Frosted Flakes |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

243.3 |

10.0 |

|

Honey Nut Cheerios |

General Mills |

Minneapolis, MN |

239.6 |

38.3 |

|

Honey Bunches of Oats |

Kraft Foods |

Tarrytown, NY |

222.8 |

17.8 |

|

Cinnamon Toast Crunch |

General Mills |

Minneapolis, MN |

164.9 |

24.9 |

|

Cereal Bars |

|

|||

|

Chewy Granola |

Quaker Oats |

Chicago, IL |

125.7 |

2.8 |

|

Nature Valley |

Campbell Mithun |

Minneapolis, MN |

107.6 |

7.1 |

|

Nutri-Grain |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

102.5 |

23.3 |

|

Rice Krispies Treats |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

70.5 |

n/a |

|

Crackers |

|

|||

|

Ritz |

Kraft Foods |

Glenview, IL |

232.4 |

12.9 |

|

Pepperidge Farm Goldfish |

Campbell Soup Company |

Camden, NJ |

167.8 |

9.1 |

|

Premium Saltines |

Kraft Foods |

East Hanover, NJ |

157.5 |

n/a |

|

Cheez-It Savory |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

139.8 |

22.2 |

|

Wheat Thins |

Kraft Foods |

East Hanover, NJ |

126.2 |

21.9 |

|

Triscuit |

Kraft Foods |

East Hanover, NJ |

108.2 |

16.3 |

|

Salty Snacks |

|

|||

|

Lay’s |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

743.1 |

23.7 |

|

Doritos |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

657.0 |

9.7 |

|

Tostitos |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

417.0 |

1.3 |

|

Cheetos |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

380.3 |

2.4 |

|

Wavy Lay’s |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

278.3 |

n/a |

|

Brand |

Company Name |

Headquarters |

Total Sales ($ millions) |

Marketing Media Expenditures ($ millions) |

|

Refrigerated Orange Juice |

|

|||

|

Tropicana Pure Premium |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

1,149.8 |

31.9 |

|

Minute Maid |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

402.8 |

28.1 |

|

Florida’s Natural |

Citrus World |

Lake Wales, FL |

234.2 |

20.7 |

|

Refrigerated Yogurt |

|

|||

|

Yoplait |

General Mills |

Minneapolis, MN |

283.5 |

36.0 |

|

Yoplait Light |

General Mills |

Minneapolis, MN |

174.4 |

n/a |

|

Dannon Light |

Dannon Company |

Tarrytown, NY |

164.1 |

3.9 |

|

Luncheon Meats |

|

|||

|

Oscar Mayer |

Kraft Foods |

Madison, WI |

808.8 |

18.0 |

|

Hillshire Farm Deli |

Sara Lee Corporation |

Chicago, IL |

244.0 |

20.1 |

|

Buddig |

Carl Buddig & Company |

Homewood, IL |

138.0 |

0.1 |

|

Meat Alternatives |

|

|||

|

Morningstar Farms |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

73.7 |

8.9 |

|

Boca Burger |

Kraft Foods |

Madison, WI |

53.1 |

1.7 |

|

Morningstar Farms Grillers |

Kellogg NA Company |

Battle Creek, MI |

28.2 |

n/a |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, from BrandWeek (2005). ©Brandweek Research 2005 / Sources: Information Resources, Inc. (sales); TNS (media). Sales data reflect U.S. supermarkets, drugstores, and mass merchandisers, excluding Wal Mart. |

||||

TABLE 4-5 Leading Beverage Brands, Total Sales, and Marketing Media Expenditures by Category, 2004

|

Brand |

Company Name |

Headquarters |

Total Sales (millions of cases)* |

Marketing Media Expenditures ($ millions) |

|

Carbonated Soft Drinks |

|

|||

|

Coke Classic |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

1,832.7 |

123.4 |

|

Pepsi |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

1,179.5 |

104.0 |

|

Diet Coke |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

998.0 |

22.8 |

|

Mountain Dew |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

648.0 |

52.5 |

|

Diet Pepsi |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

625.0 |

32.9 |

|

Sprite |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

580.5 |

43.9 |

|

Dr Pepper |

Cadbury Schweppes |

London, U.K. |

574.1 |

68.8 |

|

Caffeine Free Diet Coke |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

170.0 |

n/a |

|

Diet Dr Pepper |

Cadbury Schweppes |

London, U.K. |

140.1 |

24.6 |

|

Sierra Mist |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

138.8 |

41.4 |

|

Brand |

Company Name |

Headquarters |

Total Sales ($ millions) |

Marketing Media Expenditures ($ millions) |

|

New Age/Sports/Water |

|

|||

|

Gatorade |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

2,648.9 |

127.6 |

|

Aquafina |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

1,061.1 |

21.4 |

|

Dasani |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

925.1 |

17.5 |

|

Lipton |

PepsiCo |

Purchase, NY |

668.3 |

0.2 |

|

Red Bull |

Red Bull NA |

Santa Monica, CA |

594.5 |

31.6 |

|

Snapple |

Cadbury Schweppes |

London, U.K. |

531.1 |

10.5 |

|

Minute Maid Single Serve |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

503.4 |

35.7 |

|

Powerade |

The Coca-Cola Company |

Atlanta, GA |

460.2 |

10.5 |

|

Poland Spring |

Nestlé Waters |

Greenwich, CT |

450.3 |

3.1 |

|

AriZona |

Ferolito |

Vultaggio, NY |

369.0 |

n/a |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, from BrandWeek (2005). ©Brandweek Research 2005 / Sources: Beverage Digest (sales in millions of cases); TNS (media). *Total sales in dollars were not reported. |

||||

serve as socially responsible corporate stakeholders in the response to childhood obesity. In making positive changes that expand consumers’ selection of healthier foods and beverages, despite the challenges of market forces and the marketplace, companies may also be seeking to avoid the risk of either stronger government regulation or litigation possibilities that have been identified by industry analysts (FitchRatings, 2004; JP Morgan, 2003; UBS Warburg, 2002).

Food and Beverage Retailers

In 2004, Americans visited supermarkets an average of 2.2 times per week (FMI, 2004). A supermarket is defined as any full-line, self-service grocery store generating a sales volume of $2 million or more annually (FMI, 2004). Supermarket sales in 2004 totaled $457.4 billion (FMI, 2004). Several supermarket designs exist in the United States including conventional, superstore, combination food and drug, warehouse clubs, economy limited-assortment store,6 and hypermarket7 (Kaufman, 2002). A variety of principles shape the marketing strategies of food retailers: penetration, to attract the maximum number of households; frequency, to engage shoppers so they will make repeat shopping trips; and spending, to encourage consumers to purchase more during each trip (ACNielsen, 2004). Carbonated beverages, candy, and snack foods were identified as top food categories that drove penetration and frequency in 2003 (ACNielsen, 2004; Kelley et al., 2004).

A recent consumer survey conducted by the Food Marketing Institute found that women are the primary grocery shoppers in two-thirds of households, and only 16 percent have a shared responsibility between women and men. According to the survey, the most common reasons why shoppers report not eating a healthful diet is the desire for convenience foods (which they believe are not as healthful as home-prepared meals), perceived cost, and confusion about what constitutes healthful choices (FMI, 2003). The survey found that younger shoppers are especially interested in prepared foods, partly because they report that food preparation is more difficult for them.

Shopping frequency in traditional retail outlets, such as grocery stores, declined from 1993 to 2001 (Deutche Bank Securities, 2004) but increased in superstores (e.g., Wal-Mart), warehouse clubs (e.g., B.J’s, Costco, Sam’s), and nontraditional outlets such as convenience stores and drug stores, which are among the fastest growing venues where shoppers purchase food (ACNielsen, 2004; Deutche Bank Securities, 2004). Food merchandising at drug stores has increased in recent years with the more aisles offering seasonally available, limited assortments of food. In 2003, food and beverages led drug store sales at 27 percent of total sales. Candy was the third largest category of food sold in drug stores, based on total sales, followed by carbonated beverages (ACNielsen, 2004).

Full Serve and Quick Serve Restaurants

People are getting their meals from outside the home more often. In 2002, approximately half (46 percent) of Americans’ food dollar was spent on away-from-home foods that were either fully prepared and eaten either outside the home or brought into the home for consumption, up from 27 percent of Americans’ food dollar in 1962 (Variyam, 2005b; Table 4-2). With increases in household incomes and the proportion of two-working-parent families, a larger share of food spending is devoted to prepared and out-of-home foods and meals (Jekanowski, 1999; Kaufman, 2002; Variyam, 2005a). The share of Americans’ daily caloric intake from away-from-home foods increased from 18 percent in 1977–1978 to 32 percent in 1994–1996 (Variyam, 2005b).

Restaurants have become part of the American lifestyle. The restaurant industry estimates that the full serve restaurant and quick serve restaurant (QSR)8 or fast food restaurant sector will provide approximately 70 billion meals or snacks to U.S. consumers in 2005 (NRA, 2005). More than 900,000 commercial restaurants are projected to generate an estimated $476 billion in annual sales in 2005, up from $42.8 billion in 1970 (NRA, 2005). Consumer per-capita spending at fast food outlets such as QSRs are expected to rise by 6 percent between 2000 and 2020 (Stewart et al., 2004). In 2004, the leading 10 QSR chains accounted for $73.4 billion in sales (Table 4-6).

TABLE 4-6 Leading QSR Chains by Total Sales and Marketing Media Expenditures, 2004

|

Brand |

Segment |

Company Name |

Headquarters |

Total Sales ($ billions) |

Marketing Media Expenditures ($ millions) |

|

McDonald’s |

Burger |

McDonald’s Corporation |

Oak Brook, IL |

24.4 |

528.8 |

|

Wendy’s |

Burger |

Wendy’s International |

Dublin, OH |

7.7 |

331.3 |

|

Burger King |

Burger |

Burger King Corporation |

Miami, FL |

7.7 |

287.1 |

|

Subway |

Sandwich |

Doctor’s Associates |

Milford, CT |

6.3 |

287.1 |

|

Taco Bell |

Mexican |

Yum! Brands, Taco Bell Corporation |

Irvine, CA |

5.7 |

194.4 |

|

Pizza Hut |

Pizza/pasta |

Yum! Brands, Pizza Hut |

Dallas, TX |

5.3 |

185.2 |

|

KFC |

Chicken |

Yum! Brands, KFC Corporation |

Louisville, KY |

4.9 |

212.1 |

|

Starbucks |

Snack |

Starbucks |

Seattle, WA |

4.8 |

26.4 |

|

Dunkin’ Donuts |

Snack |

Dunkin’ Brands |

Canton, MA |

3.4 |

61.8 |

|

Domino’s Pizza |

Pizza/pasta |

Domino’s Pizza |

Ann Arbor, MI |

3.2 |

130.8 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, from BrandWeek (2005). ©Brandweek Research 2005 / Sources: Technomic (sales); TNS (media). |

|||||

TABLE 4-7 Major Trade Associations Representing U.S. and Global Food and Beverage Manufacturers and Distributors

|

Association |

Segment Represented |

|

American Bakers Association |

Wholesale baking industry |

|

American Beverage Association |

Beverage manufacturers, marketers, distributors, franchise companies of nonalcoholic beverages |

|

Food Products Association |

Food and beverage manufacturers |

|

Grocery Manufacturers Association |

Branded food, beverage, and consumer product companies |

|

International Dairy Foods Association |

Dairy food manufacturers, marketers, distributors, and industry suppliers |

|

National Confectioners Association |

Confectionery and candy manufacturers and suppliers |

|

National Restaurant Association |

Full serve restaurants and QSRs |

|

Snack Food Association |

Snack manufacturers and suppliers |

|

United Fresh Fruit & Vegetable Association |

Growers, shippers, processors, brokers, wholesalers and distributors of produce |

Trade Associations

Trade associations represent their industry members in several capacities including government relations, regulatory guidance, media interactions, and nutrition institutions. These organizations often compile data on annual industry sales and consumer trends pertaining to their segments, educate manufacturers on technological advances and retailing practices, offer standards and guidelines for practice, and provide their member companies with technical research and support. A variety of trade associations represent different segments of the food and beverage industry, retail and wholesale sectors, and the restaurant industry (Table 4-7).

Growing Purchasing Power of Children and Youth

Children and youth collectively represent a powerful economic and demographic segment. They are a primary market, spending discretionary income on a variety of products that they acquire from allowances and other sources. Children and youth are also an influence market, determining a large proportion of what is spent by parents and households. Finally, children and youth are the future market, representing tomorrow’s adult customers for branded products and services (McNeal, 1999; MPA, 2004a).

With discretionary income from allowances and other sources including gifts from parents, relatives, and friends, household chores, and outside

jobs (Doss et al., 1995; McNeal, 1998; Teenage Research Unlimited, 2004), in 2002 children ages 4–12 years spent $30 billion on direct purchases (Schor, 2004), up from $6.1 billion in 1989 and $23.4 billion in 1997 (McNeal, 1999). Of the various spending categories, one-third of children’s direct purchases are for sweets, snacks, and beverages followed by toys and apparel (Schor, 2004). Of the top 10 items children ages 8–12 years reported they could select without parental permission, the top 4 were for food categories: candy or snacks (66 percent did not need permission to purchase), soft drinks (63 percent), fast food (54 percent), and breakfast cereals (49 percent) (Chaplin, 1999).

In 2003, 12- to 19-year-olds alone spent an estimated $175 billion (Teenage Research Unlimited, 2004). Income varies greatly within the teen market as the population matures (MPA, 2004a). Adolescents have more discretionary income than their peers a few decades ago. Approximately 37.2 percent of all teens ages 12–17 years have savings or checking accounts in their own name, and 5.3 percent have access to credit cards in their own name or their parents’ name (MPA, 2004a). According to Teenage Research Unlimited (2005), which provides a continuous tracking and segmentation of the U.S. teen market to assess trends, lifestyles, attitudes, product and brand usage, the total weekly spending by teens is $98.25, with Hispanic ($107.48) and African American ($100.25) teens’ weekly spending being slightly higher than white ($95.72) teen spending. As shown in Table 4-8, food or beverages—particularly candy, soda or soft drinks,

TABLE 4-8 Top 10 Items Teens, Ages 13–17 Years, Purchased with Their Own Money

|

|

Overall Teen Rank/Item |

Percent (%) |

|

|

Boys |

Girls |

||

|

1 |

Clothes |

21 |

43 |

|

2 |

Food |

30 |

31 |

|

3 |

Candy |

24 |

34 |

|

3 |

Soda or soft drinks |

26 |

32 |

|

4 |

Salty snacks |

15 |

22 |

|

4 |

CDs or recorded music |

19 |

18 |

|

5 |

Lunch |

13 |

22 |

|

6 |

Shoes |

15 |

16 |

|

7 |

Video games |

18 |

5 |

|

8 |

Jewelry |

7 |

15 |

|

9 |

Magazines |

9 |

12 |

|

10 |

Ice cream |

7 |

10 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the Roper Youth Report (2003). |

|||

and salty snacks/chips—were ranked among the top 4 items that teens ages 13–17 years last bought with their own money in 2003 (Roper Youth Report, 2003). Another marketing research study reports that younger and older children purchase candy most frequently with their own money while teens also frequently purchase gum, drinks, and other snacks in addition to candy (Yankelovich, 2003).

Shopping malls represent the most frequent shopping place for adolescents. Boys and girls ages 14–17 years who shop at malls spend a reported $46.80 per visit. They visit malls more frequently than any other age group at a rate of once weekly, and also spend the most time per visit when compared to other places (MPA, 2004a). Teens also shop in many other venues including discount stores, convenience stores, and grocery stores. Girls shop more frequently than boys at almost every shopping venue (MPA, 2004a).

Children and adolescents also influence household purchase decisions. The purchase influence of children and adolescents increases with age and is currently estimated at $500 billion annually for 2- to 14-year-olds (U.S. Market for Kids’ Foods and Beverages, 2003). In 1993, children and youth together wielded a purchase influence of $295 billion. Of this amount, children ages 3–11 years exerted a purchase influence totaling $125 billion and youth ages 12–17 years represented a purchase influence of $170 billion (Stipp, 1993). In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in the number of children and their parents who report that young consumers ages 8–17 years are playing more prominent roles in household purchasing decisions ranging from food to entertainment to media (Roper Youth Report, 2003).

Both parents and their children report that young people have the highest purchase influence on food, when compared to other nonfood spending categories such as music, electronics, and home decor (Roper Youth Report, 2003). In 2003, 78 percent of children and youth ages 8–17 years reported that they influenced family food purchases and 84 percent of their parents concurred (Roper Youth Report, 2003). Children and youth, ages 6–17 years report that they help their parents select snack foods, breakfast cereal, soft drinks, candy, cookies, and even the QSRs where they eat (Yankelovich, 2003). Marketing research has found that nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of mothers of children and teens ages 6–17 years state that their children have influence over the types of brands and groceries they buy for the family (Yankelovich, 2003). Marketing research also suggests that parents believe that their children’s preferences are important in determining where food is purchased, as 21 percent of parents in one survey report that their child’s preference for certain snack foods is an important factor in deciding where to shop (Yankelovich, 2003).

New Product Development Targeted to Children and Youth

New product development is a central focus of innovation in the food and beverage industry. A recent survey of 30 U.S. food and beverage companies found that 71 percent had reformulated products and 29 percent had introduced new products across 3,000 product categories since 2002 (GMA, 2004). Many of these were targeted to children. Annual sales of food and beverages to children and youth were more than $27 billion in 2002 (U.S. Market for Kids’ Foods and Beverages, 2003). In 2004, product introductions targeted to children appeared to account for more than 10 percent of all new food and beverage products according to an analysis of the ProductScan® database (Harris, 2005). Candy was the largest category (46 percent) and others included snacks (8 percent), cookies (6 percent), cereals (5 percent), and beverages (5 percent). Nearly half of the new beverage products were fruit and fruit-flavored drinks. About 15 percent of all new children’s foods and beverages between 2000 and 2004 were whole-grain, low-fat, and low-sugar products, up from 9 percent for the previous 5 years (Harris, 2005).

Proliferation of Children’s Products

The committee analyzed the 50 food categories and 16 beverage categories contained in the ProductScan® database for trends in new product introductions targeted to children (Williams, 2005b). ProductScan® is an online global database that has tracked new consumer products and packaged goods introductions into the U.S. marketplace since 1980 (Marketing Intelligence Service, 2005). In the ProductScan® database, a new product is defined as a packaged, branded item that constitutes a new brand, line, variety, package type, package size or formulation, introduced to the retail shelf within the previous 90 days (Williams, 2005b).

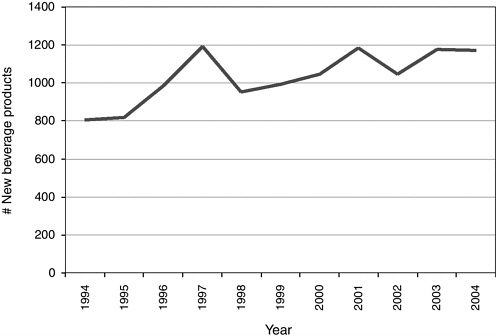

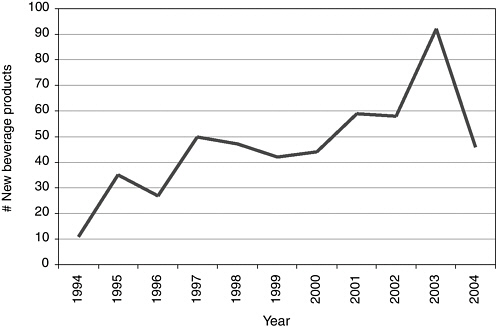

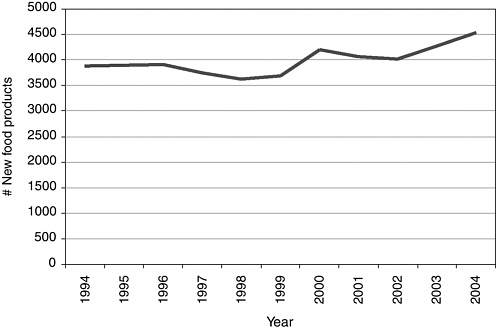

Since 1994, the ProductScan® database has been structured to allow identification of products specifically targeted to children (ages 4–12 years) and to teens (ages 13–19 years). Searching the full 1980–2004 database using the keyword “children,” suggests generally that new products targeted to children during 1980–1994 were significantly fewer than from 1994 to the present (Williams, 2005b). However, the age specificity of the search capacity has been improved for recent years. Figure 4-2a shows the year-by-year new product introductions in the ProductScan® database from 1994 to 2004 for all food products targeted to the total market and Figure 4-2b shows the year-by-year new product introductions in the ProductScan® database from 1994 to 2004 to children and youth. The number of new food and beverage products targeted to children and adolescents by

FIGURE 4-2a New food products targeted to the total market, 1994–2004.

SOURCE: Williams (2005b).

company, manufacturer, or distributor from 1994–2004 is shown in Appendix E, Table E-2.

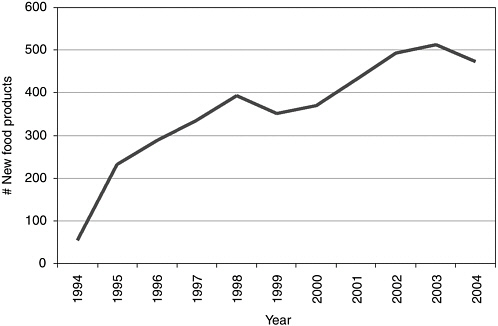

Figure 4-3a shows similar data for all beverage products targeted to the total market, and Figure 4-3b shows data for beverage products targeted specifically to children and adolescents.

For both foods and beverages, the overall trend lines increased upward from 1994 to 2004, but as indicated by the slope of the trend lines, the growth rate in new product introductions for both food and beverage products targeted to children and youth is greater than the growth rate for food and beverage products targeted to the general market. The decline that occurred between 2003 and 2004 for both food and beverage products targeted to children and youth, relative to those targeted to the general market, may be due to recent scrutiny addressed to the introduction of new products targeted to children. It is uncertain whether the recent decline in new products targeted to children is attributed to an overall

FIGURE 4-2b New food products targeted to children and adolescents, 1994–2004.

SOURCE: Williams (2005b).

decrease in all new products, or whether it represents a selective reduction in certain categories, such as those products deemed to be less healthful for children and youth. Overall, in the period 1994–2004, there were 3,936 new food products and 511 new beverage products targeted to children and youth (Williams, 2005b). Products high in total calories, sugar, or fat and low in nutrients dominated the profile of new foods and beverages targeted to children and youth, as indicated in Tables 4-9 and 4-10.

For example, for food products, the categories of candies, snacks, cookies, and ice cream accounted for 58 percent of all new products targeted to children in 1994–2004, compared to 27 percent of all new products targeted to the general market. For beverage products, the categories of fruit and fruit-flavored drinks accounted for 40 percent of all new products targeted to children, compared to 22 percent of all new products targeted to the general market. These results concur with those reported by Harris (2005). On the other hand, one industry analysis has forecasted that healthful food and beverage products for children will be among the most active and profitable new product categories for industry over the next 5 years from 2005 to 2009 (Business Insights, 2005b).

TABLE 4-9 Top Food Categories for New Products Targeted to Children and Adolescents, 1994–2004

|

Category |

Number of New Products |

|

Candies—nonchocolate |

1,407 |

|

Chewing gum |

354 |

|

Snacks |

265 |

|

Candies—chocolate |

236 |

|

Cereals |

231 |

|

Cookies |

225 |

|

Meals |

171 |

|

Ice cream & frozen yogurt |

168 |

|

Pasta |

98 |

|

Yogurt |

77 |

|

Crackers |

71 |

|

Snack bars |

70 |

|

Pastry |

66 |

|

Desserts |

55 |

|

Cheese |

50 |

|

Mixes |

49 |

|

Fruits |

41 |

|

Sweet toppings |

27 |

|

Cakes |

25 |

|

Chips |

25 |

|

Popcorn |

25 |

|

Soup |

21 |

|

Bread products |

20 |

|

Jams |

20 |

|

Poultry |

16 |

|

Nut butters |

13 |

|

Vegetables |

11 |

|

Meat |

11 |

|

Sauces & gravies |

11 |

|

Meat substitutes |

10 |

|

Catsup |

10 |

|

Meal replacements |

9 |

|

Fish |

8 |

|

Staples |

8 |

|

Baby food |

6 |

|

Rice |

4 |

|

Salad dressings |

4 |

|

Spices |

3 |

|

Nuts & seeds |

2 |

|

Dairycase foods |

2 |

|

Mustard |

2 |

|

Sauces |

2 |

|

Salads |

1 |

|

Entré mixes |

1 |

|

Category |

Number of New Products |

|

Margarine, butter, & spreads |

1 |

|

Oil, shortening, & cooking sprays |

1 |

|

Pickles, olives, & condiments |

1 |

|

Dips & salad toppings |

1 |

|

Miscellaneous foods |

1 |

|

Total |

3,936 |

|

SOURCE: Williams (2005b). |

|

TABLE 4-10 Top Beverage Categories for New Products Targeted to Children, 1994–2004

|

Category |

Number of New Products |

|

Fruit drinks |

203 |

|

Milk, nondairy milk, & yogurt drinks |

96 |

|

Beverage mixes & flavorings |

60 |

|

Carbonated soft drinks |

39 |

|

Bottled water |

34 |

|

Sports beverages |

34 |

|

Health drinks |

10 |

|

Baby beverages |

10 |

|

Vegetable drinks |

3 |

|

Miscellaneous drinks |

22 |

|

Total |

511 |

|

SOURCE: Williams (2005b). |

|

Finding: Children and youth ages 4–17 years have increasing discretionary income and purchasing capacity, are being targeted more directly by marketers, and frequently spend their discretionary income on high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages.

Children’s Versions of Classic Products

In addition to the development of new products oriented to children and youth, food and beverage companies have devoted considerable attention to enhancing the appeal of existing products to a younger market, using novel package designs, names, and co-branding with recognizable cartoon or fictional characters (Mintel International Group Ltd., 2003). For example, Heinz introduced Heinz EZ Squirt™, a “kid-friendly”

ketchup, available in “Blastin’ Green” and “Funky Purple” colors, and substantially increased the company’s market share in 2003 (McGinn, 2003). However, like many products, they proved to have a short-lived novelty appeal and were withdrawn from the market soon after their introduction.

By contrast, conventional wisdom suggested that children would not like yogurt due to its generally sour flavor. Yogurt has demonstrated an interesting evolution both in product and child taste adaptation. Whole new products have been introduced that appeal to children’s preferences for sweet tastes. Dannon pioneered children’s yogurt with Dannon Sprinklin’s®, a version of its regular yogurt flavors with candy sprinkles encased on the cap that children could add to the yogurt (Dannon, 2005). Dannon later developed a drinkable yogurt called Danimals®, and Frusion® smoothies, a 10-ounce bottle of real fruit and low-fat yogurt within its child product portfolio. Both of these brands offer sweeter yogurt taste and portability for children (Dannon, 2005). General Mills followed with several innovations in the yogurt category that intended to make yogurt appealing to children. The first of these products was a line extending its Trix® cereal into its Yoplait® yogurt line with a mixed fruit and sweetened formulation of traditional yogurt (General Mills, 2005a). General Mills changed the yogurt packaging format with the launch of Go-Gurt®, which comes in long tubes, and Go-Gurt® smoothies that are sold in small plastic bottle-shaped containers (General Mills, 2005b). Other companies that have developed and market dairy-based products for children include Kraft Foods, which developed Twist-ums™ string cheese sticks, and The Coca-Cola Company, which manufactures Swerve™, a milk-based beverage product consisting of 51 percent skim milk (The Coca-Cola Company, 2005a).

Convenience and Portability

Convenience and portability have become guiding principles in the food company business. Swanson & Sons began this trend when the company created the first TV dinner in 1953 (Lauro, 2002). The dinners were marketed as quick meals that required minimal preparation time. The meals came in various forms and generally included meat, a starch, a vegetable, and dessert. In the 1960s, Swanson removed the words “TV dinner” from the packaging and has since introduced lighter meals in microwave-safe trays for consumers. Swanson TV dinners still remain in the public memory as the dinner phenomenon of the 1950s generation that grew up with television (Pinnacle Foods Corporation, 2003).

Easy preparation of meals has allowed children greater flexibility and independence in preparing their own meals. The concept of the TV dinner evolved into child-targeted variations of the dinner meal in the 1980s.

ConAgra Foods launched Kid Cuisine® as a line of frozen food entrés intended especially for children and young teens (ConAgra Foods, 2004). Using various character appeals, first a cartoon chef and later an animated penguin, Kid Cuisine® offered meals similar to Swanson TV dinners. ConAgra Foods markets 11 different varieties of the Kid Cuisine® meal, from chicken breast nuggets to alien invasion pepperoni pizza (ConAgra Foods, 2004).

Marketing research conducted by Nickelodeon suggests that nearly three-quarters of children and youth report that they decide on their own what they eat for breakfast most or all of the time (Smalls, 2005b). Breakfast options have undergone substantial innovations over the past 40 years from ready-to-eat (RTE) sweetened breakfast cereals to breakfast bars and pastries. The breakfast pastry category was pioneered by the Kellogg Company with the introduction of Pop-Tarts® in 1963, allowing children to prepare their own breakfasts by putting a flat pastry into the toaster, an approach since adopted by a number of companies. The company has doubled sales in the United States from 1 billion in the early 1990s to an estimated 2 billion Pop-Tarts® annually (Prichard, 2003). Other breakfast innovations with child appeal include a number of breakfast bars by various companies with ingredients ranging from cereal, fruit, and milk to chocolate and cookies.

A new lunch combination category was specifically designed for children by Kraft Foods in 1988 when the Oscar Mayer Lunchables® was launched (Kraft Foods, 2005a). This line of convenience foods was the first prepackaged, RTE lunch that offered meat, cheese, and crackers, now in three sizes of packages—the largest with 40 percent more food (Kraft Foods, 2005a). Sports drink beverages have also become popular over the past three decades. Gatorade® Thirst Quencher was created in 1965 at the University of Florida to help athletes stay hydrated during active sports (Gatorade, 2004), and now represents a category of products marketed widely as a product for children and youth.

Finding: Child-targeted food and beverage products have steadily increased over the past decade, and are typically high in total calories, sugars, salt, fat, and low in nutrients.

MARKETING STRATEGIES, TACTICS, AND MESSAGING

Advertising and Marketing of Foods and Beverages in the United States

The scope of marketing expenditures in the United States is very large. Gross marketing expenditures in 2004 for all products, including food, beverages, and other manufactured items, totaled $264 billion, including

TABLE 4-11 U.S. Advertising Spending in Selected Food-Related Categories by Purchased Measured Media, 2004

|

Category |

Total Measured Media ($ millions) |

U.S. Measured Media |

|

|

Magazine |

Newspaper |

||

|

Food, beverages, candya |

6,840 |

1,743 |

51 |

|

Restaurants and fast food |

4,418 |

179 |

176 |

|

aThis category includes beverages, confectionery, snacks, dairy, produce, meat, bakery goods, prepared foods or ingredients, and mixes and seasonings (Brown et al., 2005). SOURCE: Brown et al. (2005). Reprinted with permission from the June 27, 2005, issue of Advertising Age. © Crain Communications, Inc. 2005. |

|||

$141 billion for advertising in measured media (Brown et al., 2005). Appendix E, Table E-3 lists selected leading advertisers ranked by category, total U.S. revenues, and total advertising spending for 2003 and 2004. The committee does not have a definitive breakout of the portion devoted to food and beverages. As a proxy, Table 4-11 displays total advertising spending in measured media for selected categories: food and beverages including candy, and restaurants and fast food outlets.

An estimated $6.84 billion was spent on advertising in the food, beverage, and candy category, and $4.42 billion was spent on advertising for restaurants and fast food for a total of $11.26 billion in food and beverage advertising (Brown et al., 2005; Table 4-11). In 2003, food marketers spent $1.75 billion to advertise products to children on national cable television alone, which included NICK ($756.5 million), TDSN ($86 million), and TOON ($910 million) (Nielsen Monitor-Plus, 2005). The children’s media and entertainment industry are represented by four major companies—Disney, Time Warner, News Corporation, and Viacom—which own several forms of children’s media production and distribution systems, including ownership in broadcast networks and children’s cable networks (Allen, 2001).

Advertising intensity is one measure of the marketing emphasis given to a product category. It represents the ratio of a food’s share of advertising to its share of consumers’ disposable income. Although food accounts for approximately 16 percent of total advertising, it accounts for a much smaller percentage of disposable income, suggesting a high level of advertising intensity. This intensity varies significantly across different food categories. In 1999, confectionery and salty snacks (e.g., candy, gum, mints, cookies, crackers, nuts, and chips) accounted for 13.2 percent of total food advertising expenditures, but only 5.4 percent of the household food budget share, which represented an advertising intensity of 2.4, the highest of any food

|

Outdoor |

Television |

Cable Network |

Radio |

Internet |

|

78 |

3,418 |

1,331 |

140 |

79 |

|

204 |

3,123 |

567 |

147 |

22 |

category examined (Gallo, 1999). CSDs have an advertising intensity of 1.8, the third highest category. Fruits, vegetables, and grains have the lowest advertising intensity of 0.1—though these products account for 1.9 percent of advertising expenditures, they represent 14.7 percent of food-at-home budget shares (Gallo, 1999). More recent data for advertising intensity of various food and beverage categories are not available.

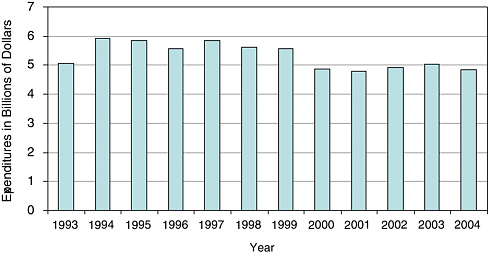

Changing Composition of Marketing Expenditures

There is evidence that the balance between advertising in measured media and other marketing techniques is changing. Available analyses use different techniques, data, and time frames, complicating precise tracking of trends. One unpublished analysis of estimated inflation-adjusted expenditures for U.S. food and restaurant television advertising from 1993 to 2004, based on Nielsen Media Research data, has suggested that real expenditures on food and restaurant advertising on television viewed by adult, child, and youth audiences have fallen over the past decade, from nearly $6 billion in 1994 to less than $5 billion in 2004 (Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services, 2004; Figure 4-4).

Industry sources have reported several converging trends that are attributed to reducing television’s effectiveness in reaching consumers and target markets, including declining brand loyalty across a variety of product categories, audience fragmentation9 across different channels and di-

FIGURE 4-4 Estimated inflation-adjusted expenditures on food, beverages, and restaurant advertising on television, 1993–2004.

NOTE: Based on an analysis of Nielsen Media Research data.

SOURCE: Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services (2005b).

verse media platforms, increased advertising costs, rising price elasticity, and increased trade promotion spending by food and beverage manufacturers that is accompanied by decreased spending for advertising and consumer promotion (Deutche Bank Securities, 2004; Smith et al., 2005). Industry and marketing sources suggest that food and beverage companies and restaurants have been progressively reducing their television advertising budgets, reinvesting in other communication channels, and using integrated marketing strategies to reach consumers more effectively (Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services, 2005b; Deutche Bank Securities, 2004). An independent analysis that could confirm these trends was not available to the committee.

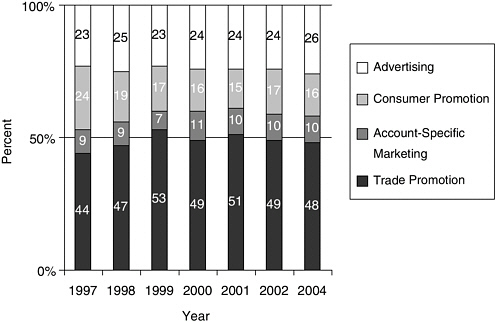

A recent trade promotion spending and merchandising study, based on 400 responses from an array of retailers and manufacturers across all connected sectors (Cannondale Associates, 2005), estimated the general distribution of companies’ marketing expenditures for trade promotion, account-specific marketing, consumer promotion, and advertising from 1997 to 2004 (GMA Forum, 2005) (Figure 4-5). In general, for all companies, trade promotion was approximately 44 percent of marketing expenditures in 1997 and 48 percent in 2004. Advertising expenditures increased slightly from 23 percent in 1997 to 26 percent in 2004 (GMA Forum, 2005). Marketing budget allocations may differ based on the type of company and the size of the company, with food companies generally allocating more for

FIGURE 4-5 Allocation of all companies’ marketing expenditures (including food companies), 1997–2004.

NOTE: See pages 137-138 for a description of marketing categories.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, from GMA Forum (2005).

trade promotion than other types of companies. One analysis indicates that food companies devote 55 percent of their marketing budgets for trade promotion, 25 percent for consumer promotion (including account-specific marketing), and 20 percent for advertising (GMA Forum, 2005).

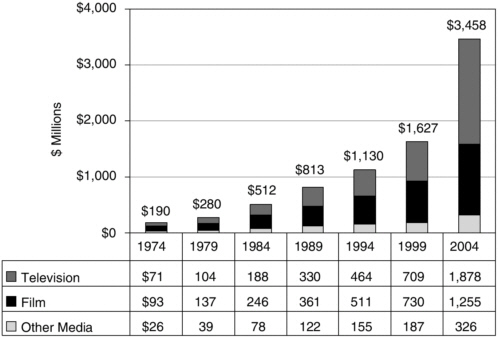

Although expenditures on traditional television advertising for food and beverage products have slowed over the past decade, television still remains the primary promotional medium when compared to other measured media categories (Brown et al., 2005; Table 4-11). It appears that more food, beverage, and restaurant advertising dollars are shifting from television into unmeasured media sales promotion (e.g., product placement, character licensing, in-school marketing, special event marketing) (Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services, 2004, 2005b; PQMedia, 2005). For example, the investment in the value of all product placement increased from $190 million in 1974 to $3.46 billion in 2004, reflecting a trend away from traditional advertising to alternative marketing strategies (PQMedia, 2005; Figure 4-6). From 1974 to 2004, all product placement (including food and beverages) in television increased from $71 million to $1.88 billion. During the same period, as reported by

FIGURE 4-6 Product placement spending in media, 1974–2004.

NOTE: Other media include magazines, newspapers, video games, music, books, radio, and the Internet.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, from PQMedia (2005).

PQMedia (2005), product placement expenditures in film increased from $93 million to $1.26 billion, and increased more slowly in other media such as video games, magazines, music, books, and the Internet, from $26 million to $326 million (Figure 4-6).

Finding: Television is the primary promotional medium for measured media marketing of food and beverage products to children and youth, but a notable shift is occurring toward unmeasured sales promotion (e.g., product placement, character licensing, in-school marketing, special event marketing).

Advertising and Marketing to Children and Youth

In 2004, an estimated $15 billion was spent on all advertising and marketing directed at children and youth (Schor, 2004), of which a substantial share was devoted to food and beverage marketing. Advertising food and beverage products to children began to emerge in the United States as early as the 1950s (Guest, 1955), and grew during the 1960s,

with the growth of the baby boomers as an untapped consumer market (McNeal, 1964, 1999). Over the decade of the 1990s, there was an estimated 20-fold increase in expenditures on advertisements that targeted children (Strasburger, 2001). Currently, advertising and marketing reach young consumers through many settings (e.g., schools, child care, grocery stores, shopping malls, theaters, sporting events, sponsored events, kids’ clubs) and media (e.g., network and digital television, cable television, radio, magazines, books, the Internet, video games, and advergames). Marketing is both direct, targeted to children and youth, and indirect, targeted to mothers who are the gatekeepers of the household (Powell, 2005). Companies often design dual-marketing strategies to reach children and youth with attractive product packaging and marketing communications that promote messages emphasizing taste, convenience, and fun whereas mothers are more often targeted with messages about the nutritional qualities such as the wholesomeness or health benefits of branded products (Schor, 2004).

The expenditures on food, beverage, and restaurant marketing are substantial. The advertising component alone amounted to industry expenditures of more than $11 billion in 2004, a sizable portion of which targets young people (Brown et al., 2005; Table 4-11). Of this, an estimated $5 to $6.5 billion was spent on televised food, beverage, and restaurant advertisements (Brown et al., 2005; Collier Shannon Scott and Georgetown Economic Services, 2004, 2005a), including about $1 billion to advertise directly to young consumers, primarily through television (McNeal, 1999). Additionally, more than $4.5 billion a year is spent on promotions such as premiums and coupons, $2 billion is spent on youth-targeted public relations including event marketing and school-based marketing, and $3 billion annually is spent on food product packaging designed for children and youth (McNeal, 1999). In all, an estimated more than $10 billion per year is now expended to market food, beverage, and restaurant products to children and youth (Brownell and Horgen, 2004).

Product Appeals

Fun, taste, and product performance are the predominant appeals used in children’s food and beverage television advertising (Tseng, 2001). Television commercials use music and familiar songs and jingles to enhance the perceived quality of a brand and to serve as a vehicle for children to remember the name of a product (Scammon and Christopher, 1981; Schor, 2004). Child actors portrayed in food and beverage commercials have traditionally been depicted as having fun with their peers when they consume the advertised product (CSPI, 2003). Audiovisual production techniques accentuate and enhance positive feelings about products by using action, rapid pacing,