6

Planning and Assessment

INTRODUCTION

This chapter addresses the intersection between ecological systems and social systems by discussing the current practices of planning and assessing road projects, the environmental component in assessing and planning, and the possible solutions for integrating the two systems more effectively. The first section describes current assessments and planning processes and then describes planning at different spatial and temporal scales, different types of planning, and the interface between the planning process and the different social groups. The second section addresses issues and problems with the planning processes, and the third describes an array of ecological evaluation tools and methods used in planning and project development, including rapid assessment methods. The fourth section addresses some potential solutions, including a conceptual framework for integrating environmental factors along with other considerations in the planning phase.

STATE OF ROAD PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT PROCESSES

Impacts from transportation systems and associated projects occur at several levels of environmental organization—from the individual organism to the landscape. Therefore, planning at the transportation system level to the individual project level requires a look at all components of the area being studied. However, as noted in Chapter 3, consideration of environmental issues is usually done at subregional scales. This per-

spective has resulted in the need for various levels of planning with increasingly finer levels of study to develop the most environmentally sensitive transportation system. The ways in which laws and regulations influence environmental assessment and policies regarding roads are similar to the ways they influence other land uses (Haeuber and Hobbs 2001). The lack of assessments at larger scales is due, in part, to a lack of an overview of multiple decisions and assessments at smaller spatial and temporal scales. This gap may be addressed in a cumulative impact assessment but is rarely done in practice. Hence, regional scale or larger assessments on ecological issues, such as species movements, large habitats, and aquifer, tend to be ignored by assessment at smaller scales.

Key Elements of the Planning Process

Coordination and Collaboration

Coordination and collaboration are required so that transportation agencies can provide the opportunity for input at all phases of planning and project development. Historically, resource agencies have had limited resources for input early in the planning process. This problem has been alleviated in some states where the transportation agencies are providing funding for resource agency personnel (see later discussion on Florida and Pennsylvania). Involvement of all parties early in the process helps to identify environmental factors in transportation plans and provides the groundwork for resolving issues early in the process.

Stakeholders and Decision Making

Transportation is a critical component of our country’s economy. Therefore, all segments of the population have a stake in transportation planning, and public-involvement programs of transportation agencies have expanded. The agencies are receiving input from diverse stakeholders representing many public and private interests. The environmental community has been active in transportation planning for several decades. The environmental resource agencies also are devoting greater resources to transportation planning and project development.

Stakeholder involvement in examining ecological impacts of roads has had some success. For example, incorporating stakeholder knowl-

edge and understanding into decision making regarding road de-icing revealed tensions and inconsistencies between the mission and the operation of the institutional system as well as inadequate communication among various elements of the management system (Habron et al. 2004). However, the involvement of stakeholders facilitated understanding of the complex institutional system and helped to identify possible areas for improvements in development and implementation of watershed models. In other situations, local or even regional stakeholder groups are effective in helping to define long-term goals for an area where road development, use, or upgrades occur (e.g., MacLean et al. 1999).

Federal Role in Planning

Under current laws and programs, there is a limited role for the federal government in planning that affects both transportation and ecological resources. Often such planning is conducted at the local and state levels rather than at the federal level. When federal agencies are involved, they may have little oversight or approval roles, such as approving Clean Air Act (CAA) conformity for a transportation plan or permitting Clean Water Act (CWA) impacts for particular transportation projects. Federal agencies may have expertise in particular ecological resources and may coordinate with state and local agencies on many levels. More frequently, however, there is little coordination of information and resources that would be helpful for ecological planning associated with transportation planning. Federal agencies are involved in natural-resource planning, however. The services are required to develop recovery plans for federally listed species, and other planning efforts are conducted for forests and other natural resources. Those services could provide opportunities for coordinated planning efforts.

State and Regional Planning

State and regional transportation plans focus primarily on transportation needs, reflecting local choices for quality of life, mobility, growth, land use, and economics. Virtually all the rules and guidance for transportation plans include consideration of a variety of factors, including environmental factors, but the main emphasis is on meeting transportation needs. Traditionally, these plans involved efforts to keep the level

of service of the transportation system compatible with growth. Although the planning process that results in state and regional plans includes consideration of environmental information, environmental issues generally are not a major part of determining the content of these plans.

For many reasons, the transportation planning stage rarely involves detailed consideration of siting of transportation projects, and there is a perception that most environmental issues can be addressed when a specific project location is viewed in more detail. There is also little information concerning ecological resources available for the transportation planning process. Relatively few locations have resource plans or consolidated information on ecological resources that could assist early-phase transportation planning. Some information on environmental resources to avoid—such as parks, refuges, and endangered species habitat—is considered during planning. Other information on ecological resources might not be available or might not be in a form that is useful for the planning scale.

To the extent feasible, transportation planning processes should use all available information on ecological resources to anticipate the potential impacts of the transportation plan on the ecological structure. That would require a number of shifts in emphasis and policy. In some states and regions, natural-resource plans address regional needs for certain resources, such as watersheds and certain migratory or endangered species. For example, some regions in California have multispecies habitat-conservation plans. In other instances, information is available in state, federal and other natural-resource management agencies, although perhaps not assembled in a plan. Obtaining useful information can involve considerable interagency coordination.

The transportation planning process will then also need to make commitments to address the ecological information at the planning stage. For example, if there is a natural-resource plan or other information describing a terrestrial migration route, it would be prudent for the transportation plan to consider whether a road planned within that migration route could be relocated. Where roads that cross streams must be improved, the transportation plan could consider and address the prospect of replacing culverts with bridges or replacing older bridges with wider spanning bridges, each of which would reduce the impacts of the road structure on the waterways. Taking up these kinds of considerations at the planning stage will have benefits of more accurately projecting expenses, as well as reducing controversy at the individual project stage.

Long-Range Transportation Plans (Large Scale)

As introduced in Chapter 5, a long-range transportation plan (LRTP) must be developed for each state. This plan is reviewed annually and updated as necessary, based on air quality considerations to meet CAA standards (see Chapter 5). The development and review of this plan provide opportunities to examine environmental factors in relation to the actual transportation corridors as the plan moves forward. However, these plans are based on other factors (described in Chapter 5), such as the level of service for highways. Other than considering air quality, most LRTPs do not address environmental impacts in detail.

LRTPs exist at the state, local, or regional levels. Local and regional LRTPs are developed by metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), consisting of county and local government representatives. In some cases, the state transportation plan or state LRTP combines various local or regional plans. For locations outside MPO jurisdiction (rural locations), the state is responsible for developing the LRTP. Other governmental entities may be involved as well, such as state legislatures, state transportation commissions, or other entities.

Although some states are trying to broaden the range of considerations in LRTPs, environmental factors, such as wildlife, and other natural-resource plans are usually not considered. Rather, LRTPs usually contain a “wish list” of desired transportation projects viewed as important to economic growth. LRTPs set priorities and must identify funding sources for all listed projects, thus keeping the “wish list” realistic.

Transportation Improvement Plans (Medium Scale)

The transportation improvement plan (TIP) is the short-term, generally 2-year plan under a restricted budget that covers priority implementation projects and strategies from the LRTP. At the TIP stage, the state and regional or local entities determine which projects should be funded and proceed within the shorter time frame. Environmental concerns are not always comprehensively addressed in a TIP. Air quality issues, especially in nonattainment areas, must be addressed under federal law (see Chapter 5). This stage of planning provides the opportunity to revisit any environmental considerations identified in the LRTP to determine whether conditions have changed to make potential projects more or less environmentally compatible. TIPs also offer the opportu-

nity to identify projects that environmental sensitivity dictates should be reevaluated before being included in the TIP work program.

Project Planning (Fine Scale)

Projects identified in the TIP move on to project development, which includes environmental studies. This step is usually the first occasion when detailed (comprehensive) potential environmental impacts associated with a planned project receive environmental analysis; yet, some analysis should be done earlier. Project development studies have become thorough and consider all applicable state and federal laws. Even local laws, such as tree ordinances, are included in the studies.

Unfortunately, these projects have advanced to the point in the project-planning process that options to eliminate environmental impacts only include avoidance, minimization, and compensatory mitigation. For impacts with legal consequences, mitigation is included in the project studies so that projects can receive approval and permits. Ideally, modifications would be made earlier in the planning process.

TYPES OF ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING ACTIVITIES

Environmental planning related to transportation occurs at federal, state, and local levels. This section describes some of the more important planning activities as they relate to transportation. Many challenges that transportation agencies encounter result from a lack of coordination among the various planning activities that are often legally required. The challenges identified in the following discussion will probably persist until environmental factors are considered in all of these planning activities and the activities are coordinated. Small-scale environmental issues can be addressed accurately only at the project level—for example, how to span a stream. Determining whether a proposed road project can avoid streams or minimize the number of stream crossings might be more appropriate at a broader planning scale. Consideration of environmental issues at the planning stage could be facilitated if the various options for avoidance, minimization, and compensatory mitigation and rationale for the preferred option were better communicated to stakeholders. For example, at the planning stage, there might be several broad corridors considered for a road, and a preference might be expressed for

the one that has fewest impacts on wetlands. Nonetheless, even within that broad corridor, wetland impacts will occur, but recognition of the avoidance steps taken in early planning may help to reduce objections during project review.

Systems planning takes a top-down and broad-scale perspective, whereas project planning deals with a specific project. Many governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have other planning activities that can be integrated with transportation planning. These activities include natural-resource planning, growth management, land-use planning, and economic development planning.

Systems Planning

The state transportation system provides the opportunity to address the larger issues associated with environmental impacts. Systems-planning studies examine a multimodal transportation system and the future transportation needs at the state and interstate levels to arrive at a systems plan that is used to develop the LRTP. At this scale, environmentally sensitive corridors can be identified to determine whether moving forward with a project is in the best public interest. It is also possible to address the cumulative effects of projects on the landscape and to find means to avoid, minimize, or develop mitigation strategies for environmental impacts. This broad-scale perspective is especially important when evaluating impacts on wildlife connectivity for animals requiring large areas for maintenance of their populations.

If streamlining the environmental process is to be successful, environmental concerns associated with transportation plans and projects should be identified early so that project approval can move forward quickly. The goal of such proactive consideration of potential environmental issues would be to retain flexibility in avoidance and mitigation. Identification of issues and impacts at the systems-planning stage would allow the time and opportunity to resolve such factors before including a project into a plan.

Assessment of an environmental decision in a plan is a key part that is often overlooked (Bergquist and Bergquist 1999). Even though transportation plans (LRTP and TIP) are revisited annually, an important aspect of the planning process is that plans are frequently changed. Therefore, it is important that stakeholders continue to be involved at all phases of project planning, which can take many years and much effort.

Project-Planning and Ecological-Impact Assessment

Project-level planning and ecological-impact assessment studies are done for those projects identified in the TIP when they are advanced to the design phase. This stage can be simple or complex. Projects that are judged not to have significant impacts can be categorically excluded from environmental assessment, and those that have potentially significant environmental impacts require more extensive studies. Level of documentation and necessity of associated studies are determined as project alternatives are developed and as issues or impacts are identified.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires study of social, economic, and environmental impacts of transportation projects that involve federal actions (such as financing, approval of connection to interstate system, and permits). This requirement has resulted in standardized procedures during the project development phase for documentation of potential environmental impacts of federal actions by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). The state transportation agencies and their consultants carry out these studies. The degree of study is based on potential social, economic, and environmental impacts. As described in Chapter 5, these studies lead to documentation in one of three forms: (1) categorical exclusion (CE), (2) an environmental assessment and finding of no significant impact (EA/FONSI), or (3) an environmental impact statement (EIS). Determination of the form of report is based on the significance of potential impacts and is arrived at jointly by the state transportation agency and FHWA. If there is a question of significance of impact or controversy associated with a project, an EA/FONSI or an EIS is developed. Over 90% of state transportation projects are processed as CEs, meaning they are deemed to have minor or no impact on the environment, as most of the projects involve expansion or modification of existing roads. Approximately 3-4% are processed as an EA/FONSI, meaning that the assessment resulted in a finding of no significant impact and the environmental issues were resolved. Less than 5% of transportation projects require an EIS meaning they may have significant ecological impacts or controversy (Forman et al. 2003). All projects require environmental study of potential impacts, but the degree of investigation is done on a case-by-case basis.

A recent study of highway practices found that, for the most part, states are successful in processing their environmental documents (EA and EIS) through a discovery process involving expert input and through coordination of the resource and regulatory agencies and the various pub-

lic groups (Evink 2002). However, project delays can result because of environmental issues that require lengthy coordination.

The studies conducted during the project development phase are based on more specific information about potential project alignments and features than those conducted earlier. Therefore, the assessment of potential impacts is more complete during project development than at earlier planning stages. Problems can arise from the lack of information about associated environments. The need for long-term studies of potential impacts to the environment, such as those for a rare species, can cause unanticipated delays. Lengthy coordination with public-land managers for compatibility with land-management plans may be necessary. However, Evink (2002) found that most transportation agencies are trying to address environmental considerations. In that study, a survey indicated that Florida, Washington, Montana, and California, among others, have to finance the collection of basic environmental information on public lands before environmental analysis can be completed. Some agencies even finance the study of basic environmental factors, such as rare species occurrence, wetland functioning, and water quality, if unknown, to complete their environmental analyses. Often, these environmental issues might have been better resolved had they been identified in the early planning stages through a more complete environmental screening.

Although the NEPA document requirements are well defined, such clarity is not the case for assessment of environmental impacts associated with transportation projects. There is substantial latitude and flexibility in methods for the identification and mitigation of environmental impacts, and as a result, analytical quality varies among environmental documents developed by transportation agencies. The quality of the documents largely depends on the expertise of the scientists both within and outside the transportation agencies that are involved in the development of the documents. Therefore, a standardized analytical method could improve the overall quality of the assessments contained in the NEPA documents.

If issues and impacts are identified in the systems-planning process, the environmental impacts assessment and project development phase should provide sufficient details for resource agency signoff or the opportunity for early resolution of impact issues. FHWA recently published guidelines for better integration of transportation planning and the NEPA process (FHWA/FTA 2005). The project development and EIS

phase are the least desirable stages to resolve complex environmental issues because project schedules often compress time frames.

Related Planning Efforts

Natural-Resource Planning

Natural-resource planning is conducted by federal, state, and local agencies and by NGOs to develop management plans for lands under consideration. Most of the agency plans are legally required. Coordination with the public and with other planning processes is also required for many of these plans. However, resource limitations and the complexity of the planning process often lead to little or no coordination among such plans. In some cases, resource management plans are not completed by resource agencies or are delayed because of limited resources. Hence, transportation agencies often find that they are trying to resolve resource and transportation planning issues without the needed input of plans from other agencies. This problem can lead to a long coordination process and project delays.

Growth-Management and Land-Use Planning

Similar to natural-resource planning, local growth-management planning and land-use planning are ideally combined in a coordinated effort that considers future growth and land-use patterns at the local level. Consideration of environmental factors in local growth-management planning is an important step in the process. Historically, economic, social, and political factors have dictated local growth and land-use planning at the expense of environmental factors.

Infrastructure required by local growth-management and land-use planning is designed by transportation planning. The result is traffic patterns generated by anticipated growth. When environmental factors are not adequately addressed in the local plans, the transportation agencies have problems resolving these environmental problems during project development. These plans also suffer from inappropriate scale issues and lack of detail.

Economic-Development Planning

Economic-development plans interact with local growth-management and land-use planning. Transportation is a critical factor for many businesses. Therefore, implementation of a sound transportation system is important to the economic health of a state. Economic drivers receive high priorities in planning at all levels of government. When transportation facilities, such as highways, ports, and airports, are needed in environmentally sensitive areas to facilitate development, transportation agencies often have difficulty constructing such projects. A more desirable approach would be the resolution of environmental issues during regional planning. These planning efforts offer an important opportunity to help support improved environmental considerations in transportation planning.

TRANSPORTATION ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENTS

Because of the decentralized nature of transportation planning and project development, assessment of impacts (social, economic, and environmental) takes place at different levels of government. Planning has emphasized the idea that local planning would best address local transportation needs. Therefore, counties, municipalities, regional transportation authorities, and MPOs in concert with state transportation agencies have identified transportation needs and planned transportation improvements to address those needs. The motivations for these improvements have largely been social and economic.

The objectives of environmental assessment at the planning phase of transportation development are different from those at the project development phase. During the planning phase, possible projects are studied in relation to their ability to address transportation needs. At that point, specific project features are often not well defined. Concepts are thus studied in broad terms.

Most projects in transportation plans are improvements to existing facilities, and there is an existing alignment or structure with associated environmental features. A small percentage of the transportation planning in the United States involves a new facility at a new location.

One of the assessment objectives during the early planning stage, such as during the LRTP, can be the identification of environmentally sensitive features associated with proposed transportation improvements.

Recent guidelines published by FHWA (2005) suggest how such identification might be accomplished. Early identification of potential environmental impacts would eliminate especially problematic projects or at least allow for early coordination to work out environmental issues associated with proposed actions.

A number of agencies from the federal to local levels are developing the ability to evaluate environmental concerns early (see Boxes 6-1 and 6-2). Checklists of key questions can help resource managers identify the places and issues of greatest concern (e.g., Box 6-1). These questions relate potential environmental impacts of a proposed project to overarching goals, conservation interests, and regulations. The questions force the decision maker to think about the future for the region by considering the project in view of conservation plans and adjacent land uses. The questions in such a checklist can be answered more readily if data are accessible in a spatial data base (e.g., Box 6-2). These efforts are primarily spatially based macro-scale examinations of environmental features in the area of the prospective transportation improvements. However, there is no standard assessment method required for evaluation of environmental concerns in transportation planning or project developments, and necessary data are not always available at this stage.

TOOLS AND METHODS FOR ASSESSMENT

Development of rapid assessment methods has been attempted for wetland functional analysis. The hydrogeomorphic method (HGM) of wetland functional analysis by the Corps of Engineers (Corps) is the latest effort (Brinson 1993). The HGM approach classifies a wetland based on its setting in the landscape, its source of water, and the dynamics of the water on-site. HGM has many useful applications in functional assessment, but most variables incorporated into the assessment models remain measures of wetland structure rather than processes, perhaps because of the cost of doing the functional assessment and the available staff (NRC 2001). Although methods for a few wetland types have been implemented, they have not been rapid assessment methods. Furthermore, the habitat evaluation procedure (HEP) developed by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1980 is not a rapid assessment method and has not become a standard assessment tool. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation developed a community-based, landscape-level terrestrial mitigation decision-support system (Maurer 1999) that

|

BOX 6-1 Example of a Checklist That Can Be Used in the Rapid Assessment Process: The Florida Environmental Technical Advisory Team Rapid assessment of the potential for impacts of transportation projects will require greater interagency coordination in the early planning phases of transportation development. Florida is using a team approach (environmental technical advisory team [ETAT] made up of planning, consultation, and resource protection agencies) to conduct early screening of proposed transportation projects. Because more than 90% of the transportation projects being developed are processed as “categorical exclusions” (Forman et al. 2003), the team approach to early screening could resolve environmental issues in the majority of projects. Florida’s screening process is a GIS-based system that uses habitat characterization and a series of ecologically related questions to determine the significance of the potential project impacts on the environment—in Florida’s model, social, economic, and ecological considerations are considered in the process. Using only ecological concepts, the team considers the following types of factors early in the planning process to rapidly assess the potential for impacts and to ultimately decide whether the project can be moved to categorical exclusion or whether it requires further ecological study and coordination.

|

In the Florida model, after consideration of these initial screening questions at the beginning of the LRTP process, the ETAT changes roles as the project progresses, providing further guidance and support should the project progress into the NEPA phase. For the approximately 10% of projects that cannot be categorically excluded, the screening process identifies the major environmental concerns that will need to be addressed during the process, thereby helping to accelerate conclusion of coordination and environmental documentation. |

|

BOX 6-2 Example of a GIS-Based Framework for Assessing Ecological Conditions in the Southeastern United States The southeastern ecological framework (SEF) (developed by the University of Florida in 2001) is a geographic information system (GIS)-based analysis that can identify ecologically significant areas and connectivity in the Southeast. The states included in the project are Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. The approach is designed to meet the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) goals of gathering and disseminating information pertinent to the ecological condition of a region. The framework focuses on implications for biodiversity protection, but the approach can be used for clean water and air provisions and global-change risk reduction. Data layers include conversation lands, hydrological features, wetlands, land |

|

cover, potential habitat for species of interest, shellfish harvest areas, and the 100-year floodplain. The development of a regional spatially explicit database and tools to access the information facilitates collaborative decision making, which is becoming a part of the process of environmental protection. Having spatially explicit data available for a region allows broad-scale implications to be considered in decision making. The spatial implications are important to consider because the growth of human populations and transportation systems, as well as economic development, are fragmenting natural landscapes. The need to consider connected actions and cumulative effects and to understand the geographic context where the actions will occur argues for an approach to project planning that considers a larger geographic area than that usually covered by a single project. The SEF provides a schema and contributes to the environmental decision-making capability of local communities and regions. The approach is useful for such diverse needs as community planning efforts and NEPA analysis. The SEF has been used to examine potential impacts of proposed roads. A valuable aspect of the effort to create the SEF is the coordination across federal and private sources of natural-resource data. For EPA to continue to align its programmatic efforts with performance goals at regional and national landscape levels, it will need to rely on other state and federal agencies for sources of data, models, and expertise. Conservation organizations, such as the Association for Biodiversity Information and the Nature Conservancy, will also be a valuable source of data on locations and status of ecological systems, vulnerable species, and special sites of biodiversity significance. The use of the Southeast Natural Resource Leadership Group by the SEF work group is a model for coordination efforts. In addition, the effort to create a regional model to advance the management of the ecological framework is a novel and important step forward. |

has some characteristics useful for rapid assessment. The Florida Department of Transportation has also developed a decision-making checklist based on geographic information system (GIS) data that could be used in a standardized assessment method (see Box 6-1). None of these efforts has led to a national standardized assessment method.

Tools for in situ monitoring, remotely sensed monitoring, data compilation, analysis, and modeling are constantly being improved. Ad-

vances in computer technology mean that tools for data collection and analysis are quickly getting into the hands of practitioners. However, because data are usually insufficient at the local level, remote-sensing techniques for data collection must be used when possible.

As the need for more strategic and broad-scale planning efforts to minimize the impacts of roads on ecological systems becomes apparent, various tools are being used to address the need. For example, quantifying the overall impact of new-road development on biodiversity and estimating the risk to biodiversity strongly depend on the availability, accuracy, reliability, and resolution of national data on the distributions of habitats, species, and development proposals (Treweek et al. 1998). Remote-sensing data are often useful to such analysis. Most estimates of land cover come from remotely sensed data. Data from Landsat satellites are particular useful for characterizing land cover, vegetation biophysical attributes, forest structure, and fragmentation (Cohen and Goward 2004). Satellite remote-sensing data can be used to develop maps of land cover at different times to assess changes over time in patterns and processes (e.g., Franklin et al. 2000). Monitoring such changes can be important in ecological monitoring programs at multiple spatial and temporal scales. In addition, broad-scale measures of species occurrence and behavior often rely on acoustical and video-monitoring tools or other type of remote measures of species (e.g., Sherwin et al. 2000).

Thresholds may be used to depict abrupt changes in ecological impacts, but in some cases, thresholds do not occur. For example, although excessive loading of fine sediments into rivers can result from road construction and such particles degrade salmonid spawning habitat, the linear relationship between deposited fine sediment and juvenile steelhead growth suggests that there is no threshold below which exacerbation of fine-sediment delivery is harmless (Suttle et al. 2004). Hence, any reduction in sediments could produce immediate benefits for salmonid restoration. However, thresholds can be important aspects of indicators related to road effects on habitat fragmentation (e.g., Gutzwiller and Barrow 2003) or habitat degradation (e.g., Johnson and Collinge 2004). The response of European three-toed woodpeckers (Picoides tridactylus) to different amounts of dead wood in a boreal and a sub-Alpine coniferous forest landscape in Switzerland was related to steep thresholds for the amount of dead standing trees and to a high–density road network (Butler et al. 2004).

Issues, Gaps, and Problems with Assessments

Several issues arise in the current approaches to transportation assessments. They include the lack of standardized methods, indicators, and data. Other issues are the determination of the assessment scales and the focus of the approaches on specific ecosystem components (such as an endangered species) rather than on an integrated assessment. Other issues arise around who is involved in the assessment process and how government agencies interact with other groups.

The lack of a standardized method is the result of several factors. Federal transportation regulations and guidance and Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) guidance outline in detail environmental factors that need to be considered in transportation assessments; however, those factors vary among regions, and priorities for those factors have not been established. Indicators of environmental quality or degradation have not been well defined (NRC 2000b).

Discussion continues on the temporal and spatial scale necessary to address potential impacts, especially secondary and cumulative impacts. For example, one such issue that can be assessed at multiple large scales involves the consequences of roads on fire dynamics in many parts of the country, especially in light of ENSO (El Niño/Southern Oscillation) and other broad-scale sources of climatic variability. Another largely unaddressed issue is the interaction of road networks and biota movement in context of climate change. The necessary environmental data do not exist for large areas of the country, and the data that exist lack reliability and compatibility because data vary among regions, making subsequent analysis difficult.

The existing process is a combination of coordination and an expert-opinion approach to identify the environmental factors within a project. Local and state officials are required to hold public meetings to discuss proposed plans and projects. They are also required to coordinate the plans with other state and federal agencies. A weakness in the existing system is that the information available during early planning meetings is often so inadequate and incomplete that constructive dialogue about environmental factors is put off until the project development phase, at which point it is often more difficult to reach consensus on environmentally sensitive projects. Project concepts and designs have not advanced to the point that potential environmental involvement can be identified. Often, information about the natural environments encountered during planning activities is lacking. Another weakness is the lack

of public, environmental agency, and NGO input because of lack of resources. As a result, state transportation agencies have funded resource agency staff to obtain early input (Evink 2002).

Although the transportation field is reaching a point where a national rapid-assessment method for evaluating transportation-related impacts on the environment might be developed, there are still many obstacles. First, the basic biological information needed is lacking in many areas of the country. Next, there is no central source of such information when it is available. As a result, obtaining the information requires a major coordination effort by the transportation agency. EPA is working on developing such a centralized data set (Box 6-2; Durbrow et al. 2001). Often, the transportation agencies lack resources to generate missing information and must contract with other agencies or consultants to develop even the most basic biological information. An example is the basic biological information about an endangered or threatened species and their distribution. Lack of funding in the state and federal agencies responsible for wildlife management has led to a lack of management plans for habitat and wildlife in some areas of the country. Furthermore, additional work is needed in developing and testing models that address transportation impacts on ecological systems.

A rapid assessment method could be developed to evaluate the impacts of transportation actions on the environment and to generate mitigation strategies. It would interface GIS data with analytical models and empirical data to determine potential impacts under different scenarios. However, development of such analytical tools has not been an easy task, given the lack of data, mixed data quality, need for centralized data sources, and lack of resources for the development of data and techniques as well as scientific debate on measurement techniques. Rapid assessment components continue to be developed so that they can be implemented, but coordinating a rapid assessment method with the necessary participants may become overwhelming, as was the case when developing wetland models with the Corps-sponsored HGM. The original functional assessment procedure was modified to meet different needs, and most deviate from the original intent, premise, and design (Brinson 1995, 1996). If a standardized rapid assessment method becomes a national imperative, the following are some of the actions that will be necessary to produce a universally acceptable product.

A factor limiting the development of a rapid assessment method has been the lack of uniformity of data collected at one scale of resolution, using standard means for measuring, sampling, and labeling. The need

for uniformity is especially true of data useful in GIS. Data uniformity is lacking even among agencies in many state governments, let alone in the nation. (For example, soil data are inconsistent from state to state.) State and federal agencies and industry groups have been discussing for years what format and systems should be used, and some progress has been made. The lack of uniformity also applies to the quality of data available. Many different entities are developing data, and the quality of the data is dependent on the resources and expertise brought to the task.

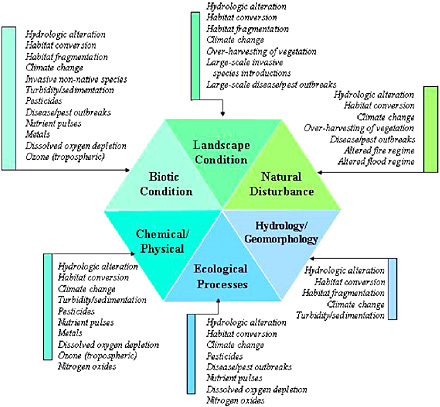

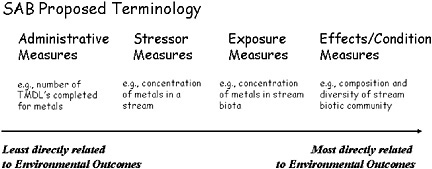

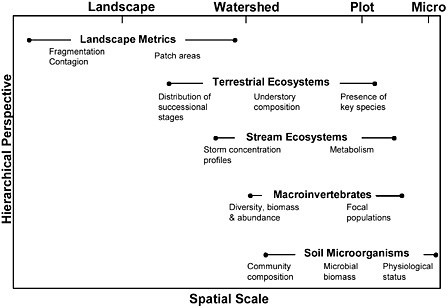

Scientific debate continues about appropriate indicators of ecological attributes. EPA developed a framework that attempts to define these multiple attributes (Figure 6-1), Dale and Beyeler (2001) developed criteria for indices, and the NRC (2000b) proposed a set of national ecological indicators and described the scientific rationale for them. There are six essential ecological attributes: (1) Landscape conditions are the extent, composition, and patterns of habitats in a landscape context. An example is the status and change in extent of a forest system. (2) Biotic condition is the viability of communities, populations, and individual biota. Examples include the presence and population trends of rare and common species. (3) Ecological processes are the metabolic functioning of ecological systems, such as energy flow, element cycling, and the production consumption and decomposition of organic matter. (4) Chemical and physical characteristics are the physical conditions (for example, temperature) and concentrations of chemical substances (for example, phosphorus) present in the environment. (5) Hydrology and geomorphology are the interplay of water and land form in the environment. Soil erosion and changes in streamflow rates fall into this category. (6) Natural disturbance regimes are the pattern of discrete and recurrent disturbances that have shaped an ecological system. Examples include wind throws, floods, and fires. Often, the relevant indices depend on the project questions and options (Figure 6-2).

Finally, the lack of mandatory legal standards or requirements for many ecological features, other than air quality, water quality, and wetlands, complicates the issues of whether and how a standard assessment method should calculate impacts or set metrics to assist with mitigation choices.

On a more positive note, scientific and technological development is leading the nation in the direction of a better understanding of the environment and the impacts of human activities. This advancement is largely the result of computer technology and the associated capabilities for data storage and analysis. Models using GIS data hold great promise and are being developed to look at diverse sets of parameters to support

decision making (see Dale 2003). An example is the landscape ecological analysis and the rules for the configuration of habitat (LARCH) model, an expert systems model that uses thematic mapping to examine ecosystems and network populations to compare different landscape scenarios to support decision making in considering project alternatives in The Netherlands (Bank et al. 2002). For mitigation, models are being developed that identify wildlife habitat linkages for planning wildlife crossing structures (Clevenger et al. 2002a).

Modeling tools are being developed to meet the needs of environmental assessment. The use of models is based on the concept that models can synthesize the current understanding of the environmental repercussions of an action. Models offer the opportunity to deal with complexities and interactions without being overwhelmed by details. In particular, future modeling should deal with scales, feedback, and multiple criteria for environmental protection (Dale 2003). Models can integrate processes that operate on various temporal and spatial scales. Incorporating feedback from different aspects of the environment that operate at different scales is one of the biggest challenges of interdisciplinary research. Environmental protection has been constrained by efforts to meet one single criterion (for example, protection of a single species or keeping water quality above a given standard). Developing approaches allow simultaneous consideration of several criteria and their interactions. The use of ecological models by decision makers also requires some improvements. These include establishing closer communication between environmental scientists and modelers, developing clearer definitions of the land and resource management issues, using models to enhance understanding, and exploring alternative future conditions (Dale 2003).

Some transportation agencies have begun to use these techniques in transportation planning and project development. Natural Heritage Programs and other state agencies are providing GIS data. A few states’ transportation agencies have even contributed to the development of these data layers. Florida has completed GIS layers for many features of the state and is using the information in systems planning and project development studies (Carr et al. 1998, Kautz et al. 1999, Smith 1999). Florida is also developing models using the GIS data to identify potential impacts on environments, given different types of factors (Box 6-1). These data are then used in coordination with resource agencies and the public to arrive at the transportation plans and subsequent projects. An

interagency effort (the Southeastern Ecological Framework) has been formed to develop this type of data for the entire southeastern United States (Box 6-2).

The state efforts are in response to the need for more complete disclosure of information related to transportation planning and project development to streamline the approval process. The internet is contributing substantially to sharing this information. State transportation agencies are posting planning and project development information on the web as part of their public involvement programs, providing a convenient opportunity for agencies, organizations, and the public to have input on a project. Another promising area from the internet is international sharing of information. Scientific information on the impacts of transportation on the natural environment is being gathered and posted at sites by several of this nation’s transportation centers (for example, the Center for Transportation and the Environment and the Western Transportation Center) and internationally by the multinational research committee COST1 effort in Europe, along with a host of university, governmental, and private sites (Evink 2002, Bank et al. 2002).

To develop standard methods, a number of steps need to be taken. First, resource agency budgets would need a major increase allocated to the development of basic biological information in a uniform format. This step would have to take place at state and federal levels to develop the data and planning necessary for input to the system. This information could be made available through a web-based system. Second, a national effort to develop environmental GIS data at the local and state level in a uniform format would be necessary. Data layers that are useful to include are land cover, roads, utility lines, soil types, hydrological units, streams and lakes, public ownership lands, and patterns of past disturbances Although some of this work is already taking place, it cannot be used in all locations of the country. A web-based system of the data would be necessary for efficient sharing of the data.

Next, interdisciplinary groups of scientists, including personnel from resource and regulatory agencies, would be tasked to identify the

|

1 |

COST is a European framework for the coordination of nationally funded research. A “COST Action” is a European Concerted Research Action based on a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by the Governments of the COST Countries wishing to participate in the Action. Each COST Action is identified by a number (e.g., 341) and a title (e.g., Habitat Fragmentation due to Transportation Infrastructure). Reference: http://www.cordis.lu/cost-transport/home.html. |

analytical models needed for the various environments encountered by transportation projects—wetlands, aquatic systems, uplands, and so forth. Research would be needed to develop the analytical models. Models that include mitigation components would need to allow examination of costs and benefits of various alternatives. The approach would involve interdisciplinary groups who would develop an interactive analytical program that would form the core of the rapid assessment methodology. Approval by a wide audience would be necessary to make the effort fruitful in the end.

Some state transportation agencies, such as Florida’s, have already proceeded along this path. However, progress is slow because of sparse funding, and lack of reliable basic data, completed land-management planning, and other information needed to make the system work. Getting consensus from resource and regulatory agencies has often been difficult because of the diversity of interests involved. Any increase in activity at the state and federal level would help provide the science to make a standardized assessment method possible.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS FOR ASSESSMENT AND PLANNING

Conceptual Considerations

Environmental assessments and planning activities involve some estimation of future events. These processes involve trying to predict environmental effects associated with a certain action, such as building or widening a road. Although broad, general outcomes are known, the ability to predict ecological outcomes is difficult and limited for many reasons. Ecological systems are complex; the scales of ecological structures and processes range widely; there are many competing ideas about the structure and functioning of ecological systems; and the lack of information and financial support to test ideas about ecological systems prevent resolution on a meaningful scale. Those problems can be applied to the social dimensions of assessment and planning. Social-dimension problems include the shifting and multiple values that society places on different aspects of ecological systems.

Another way to think about assessment and planning is that both are processes that address the consequences that may result from a proposed action. Several approaches have been developed to address and

reduce uncertainties. Those include qualitative assessments by knowledgeable persons, narratives or scenarios, strategic gaming, statistical analyses of empirical or historical data, and causal modeling (NRC 1999). Expert opinions can be used in legal situations or when causal understanding or data are lacking. The development of narratives or scenarios has been used successfully to highlight emerging issues (for example, Carson 1962) or to roughly define feasible alternative futures that contain great uncertainty. Scenario-based planning has been used in business (Shell Corporation [van der Heijden 1996]), climate-change research (Raskin et al. 1998), and exploration of sustainable futures (NRC 1999). Empirical approaches that involve statistical analyses of existing data sets are dependent on extant information in forms amenable to analysis. On the basis of the amount and type of uncertainty associated with ecological issues, all of those approaches can be used to assess resource issues in transportation. A conceptual framework is proposed in the next section as a way to improve integration of ecological considerations into transportation planning.

Conceptual Framework for a Rapid Assessment Method

The committee’s proposed conceptual framework for a rapid assessment method systematically incorporates ecological factors into transportation decision making. Its rapid assessment approach is based on those that use basic ecological principles (Stohlgren et al. 1997, Stork et al. 1997, Dale et al. 2000, Dale and Haeuber 2001). Many aspects of this approach were field tested by the Pennsylvania Department Transportation (see Maurer 1999). In addition, the Florida Department of Transportation developed a checklist (Box 6-1) using GIS data that could be the basis for a standardized assessment. In this section, the committee takes the elements of existing methods, develops a framework, and proposes that a national method be adopted.

The goal of the rapid assessment method is to provide environmental information to decision makers at several stages in the process of making decisions so that the ecological impacts of roads can be evaluated. The ecological impacts must be considered in early decisions. However, such early inclusion is possible only if the ecological information can be provided in a timely manner. Streamlining of ecological information early into the decision-making process can reduce costs.

The rapid assessment approach offers new opportunities to better protect, restore, and enhance ecological systems affected by the construction, maintenance, and operation of transportation systems. At present, this method cannot be rapid, but it should become so as the approach becomes more familiar, as the required data become more available, and as the tools for data manipulation and analyses become more widely accessible. The committee’s proposed framework calls for

-

Consideration of ecological factors early in transportation systems planning and throughout project development, maintenance, and operations.

-

Establishment of ecological goals and performance indicators along with transportation goals and performance indicators to meet ecological resource protection, restoration, and enhancement needs as well as transportation needs.

-

Identification of the ecological context of the study area in the form of the mapping and characterization of specific features of the ecological system before the development of transportation systems plans, programs, and projects.

-

Use of a context-sensitive solutions planning and design approach to explore a range of transportation solutions in lieu of a design and impact assessment approach.

-

Use of ecosystem performance assessment models to evaluate the ecological performance of alternative solutions.

-

Provision of information and involvement of the public throughout the process.

-

Monitoring and evaluation of ecological protection, restoration, and enhancement during construction, maintenance, and operations.

-

Ecological research to develop new baseline information, analysis methods, and tools.

-

Use of ecological databases and models for managing baseline, monitoring, and evaluation information.

-

Formation of multidisciplinary and multiorganizational teams that collaboratively conduct ecological analyses related to transportation issues.

-

Expansion of the consideration of ecological factors beyond transportation project development for which ecological impacts have been addressed historically through compliance with NEPA and other environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

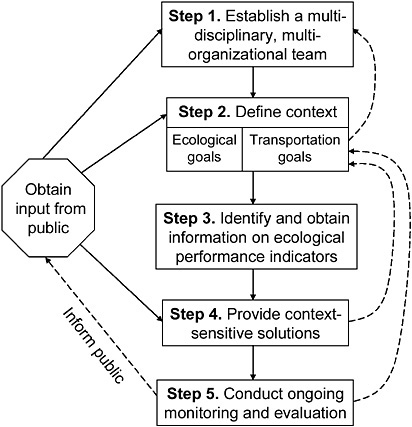

The committee’s proposed conceptual approach is described as a five-step process (Figure 6-3) in the following paragraphs.

Step 1—Establish a multidisciplinary and multiorganizational team

Before this process is begun, however, an analysis is needed of the probable effects of the project on the environment, based on considerations such as those discussed in Chapter 3. Thus, if the project is the construction of a new major highway, assessments would be conducted on the potential for habitat alteration; disturbances due to noise and light;

FIGURE 6-3 Diagram of committee’s proposed framework for a rapid assessment method.

fragmentation of habitat; interference with the dispersal of most organisms; facilitation of the spread of some organisms, possibly including exotics; a risk of deaths to mobile animals caused by collisions with traffic; possible changes to hydrological and sedimentation patterns; and the probable accumulation of contaminating chemicals, including de-icing materials in most regions of the country. If the project is a bridge replacement, resurfacing or widening of an existing road, or similar activity, then a different and smaller suite of potential environmental effects will need to be assessed. In addition to the road, the structures that will need to be identified include culverts, bridges, overpasses, on- and off-ramps, and causeways. Once the preliminary but essential assessment has been done, the remaining five steps should be followed as described below.

The team should consist of planners, engineers, and environmental professionals who have experience with the particular conditions related to ecological impacts of roads. The team members will develop and apply the method. Depending on the makeup of the team, the method could be used at the project level or the system level. It is critical, however, that the ecological impacts of roads be considered at several stages in the road planning process, especially at the early stages. As the project evolves, team membership may change as different expertise is needed. For example, if a road crosses a karst area (terrain usually formed on carbonate rock, characterized by deep gullies, caves, sink-holes, and underground drainage), a specialist may be needed.

Step 2—Define context

Defining the context requires identifying ecological and transportation goals, ecological concerns, and spatial and temporal scales of interest. The ecological goals should include protection of species of concern and habitats, specific ecological or geological features, and ecosystem services as well as transportation goals (for example, to develop a new road to meet transportation needs). The Committee of Scientists (1999) argued that meaningful planning sets both long-term goals and desired future conditions. Thus, the link between developing assessments and building decisions is in defining the desired future condition that includes both ecological and transportation goals. Defining a desired future condition requires extended public dialogue, as it is a social choice affecting current and future generations. As a future-oriented choice, a desired

future condition seeks to protect a broad range of choices for future generations, avoid irretrievable losses, and guide current management and conservation strategies and actions. Nonetheless, given the dynamic nature of ecological and social systems, a desired future condition is also dynamic over time and thus is always revisited in the decision-making process during monitoring, external review, and evaluation of performance.

The public can be involved in all stages of setting goals. From a social perspective, desired future conditions are those that sustain the capacity for future generations to maintain patterns of life and adapt to changing societal and ecological conditions (Committee of Scientists 1999). Different parts of society and different stakeholders offer interpretations of both past and possible future conditions, reinforcing the importance of the deliberative process of collaborative planning.

Ecological assessments offer independent information about ecological conditions, against which differing perspectives can be compared. This process will provide a mosaic of explanations and perspectives, all of which need to be a part of the deliberation of desired future conditions and the implications for future choices of different ecological conditions (Committee of Scientists 1999). Although choosing a particular desired future condition is a social choice, this choice is still bound by biophysical limits. Thus, the desired future condition represents common goals and aspirations.

Defining ecological concerns also requires addressing legal and social issues. Laws that protect the environment are addressed in Chapter 5 and include NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, the CWA, the CAA, and many other national and local laws and ordinances. Social issues are typically context specific and may include the need to preserve certain places that are highly valued by the community. Thus, context definition draws on the experiences of all of the stakeholders.

Step 3—Identify and obtain information of ecological performance indicators

Performance indicators for the desired future conditions are metrics that quantify the features for the desired outcome. The essential ecological attributes (see Figure 6-1) can be considered a checklist to help to develop these indicators. Some of these values may be available from existing data sources (for example, the southeastern U.S. framework; see Box 6-2). Characterization of the ecological system can be done by

quantification of the selected indicators. However, the indicators can vary over time and space (Figure 6-4). When possible and reasonable, mapping of the performance metrics provides spatial attribution of the indicators.

Other experience with environmental assessments (Holling 1978; Walters 1986, 1997) suggests that dynamic computer models for resource-managed applications can be powerful tools at this step. These models link data on chosen indicators with information on critical ecosystem factors that influence these indicators. These models also include linkages to determine how alternative design or policy options would affect indicators. GIS may provide useful information on spatial relationships and slowly changing ecological attributes but are not as effective in understanding dynamic linkages. Another attribute of this modeling approach is that it enables the technical team to assess feasibility of policies, which is critical to determination of context-sensitive solutions.

FIGURE 6-4 A suite of indicators across scales is being adopted by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Strategic Environmental Management Project. Source: Dale et al. 2002. Reprinted with permission; copyright 2002, Elsevier.

Step 4—Context-sensitive solutions

Information generated by an ecological assessment can contribute to the understanding of ecological processes, but it cannot determine what choice is right. Informed expert opinion and public dialogue is essential to determine decision options. Hence, a first step for decision making is to develop the public forum for defining the desired future condition. The decision makers can use the options generated and projections of the ecological impacts of their implementation to plan and design context-sensitive transportation solutions.

Options for meeting the transportation goals can be considered in view of their potential effects on ecological conditions. Enhancement and mitigation can be built into the array of proposed solutions. A plan can be designed to convey the information of changes in performance indicators to planners, engineers, and decision makers. Modeling and assessment tools can be used to determine whether any solutions meet (or exceed) the ecological and transportation goals. If goals are met for a proposal, then that solution may be selected. If not, then the team can use the assessment information to determine whether the impacts from a solution are acceptable. If the ecological ramifications are not acceptable, then the transportation goals may need to be reevaluated, or if the transportation consequences are too severe, then it may be necessary to reset acceptable ecological goals. This proposed process may not reduce or eliminate all issues.

Regarding proactive actions to address ecological concerns, the effect of actions driven by laws and ordinances and social concerns can be very different from those designed merely to meet the short-term intent of the law. In addition, proactive measures can serve to speed development by considering all possible negative implications of a decision and implementing solutions to a potential problem early in the process (often using actions that are relatively inexpensive to implement at the early phase, for example, small relocations).

Step 5—Ongoing monitoring and evaluation

After information from the rapid assessment process has informed decision making and a decision has been implemented, it is critical to continue monitoring and evaluating to determine whether the ecological

and transportation goals are being addressed and to provide the opportunity for mid-course corrections (Bergquist and Bergquist 1999). When corrections are necessary, it may be useful to go back to step 2 of this process (Figure 6-3) and redefine the context, obtain new information on performance indicators, reevaluate context-sensitive solutions, and reinstate a new monitoring and analysis protocol. Unfortunately, existing laws and regulations do not require reevaluations, but such reconsideration often makes sense in terms of management and budgetary needs. Planning for ongoing monitoring and evaluation requires well-maintained and accessible databases and the ability to use performance indicators to track the ecological implications of natural changes and management actions. Data and indicators are critical components of this proposed framework. In addition, such reevaluation allows for corrections to be made to correct for deficiencies in performance and for ongoing communications with the public.

Data and Indicators for Assessment

To conduct ecological impact assessments as part of transportation decision making, the transportation and ecological context of the area of potential impacts must be well defined and understood. These contexts are defined through the collection and analysis of baseline transportation and ecological data. The collection of such data usually involves a combination of acquiring existing data files and conducting supplemental field studies. The scale, quality, quantity, accessibility, and age of the existing data files on baseline conditions heavily influence the amount of supplemental field studies necessary to define the transportation and ecological contexts adequately.

Local, state, and federal transportation agencies over the past 100 years have assembled a tremendous amount of macro-scale and microscale baseline data about the transportation system. In the past 25 years, a concerted effort has been made to create national electronic transportation databases and database management standards to improve the quality and accessibility of the transportation data. With the advent of the internet and GIS, transportation agencies have developed web-accessible databases and decision-support systems that make high-quality transportation system data readily accessible for decision making at the local, state, and national levels. The FHWA in cooperation with the local,

state, federal, and tribal transportation agencies through the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials have ongoing transportation data collection and management enhancement programs to continually update and improve the quality, quantity, and accessibility of data.

Although local, state, and federal regulatory and environmental agencies and interest groups have assembled and managed a tremendous amount of baseline ecological data over periods similar to the development of transportation data, the data are typically low quality, at a macro-scale, and rarely adequate for ecological impact assessments. Very few transportation ecological impact assessments are completed with previously existing ecological data. Most often, the transportation agency environmental professionals must collect ecological field data at a micro-scale for their ecological impact assessments.

The timing and extent of supplemental field studies often drive the transportation project delivery schedule. In the case of ecological field studies, their timing and extent is usually heavily influenced by changing environmental and biological conditions that could result in several months to years of field study. In contrast, transportation field studies involve measurements that are not as heavily influenced by changing environmental and biological conditions, allowing them to be completed in weeks or months. The short time frame of transportation field studies may be inadequate to gather sufficient data on important ecological processes (such as animal migration) that may require at least 2 years to document adequately.

Ideally, high-quality ecological databases with macro-scale and micro-scale data would be readily accessible to transportation agencies to define the ecological context for ecological impact assessments. They would be developed and operated in accordance with national database standards. Such databases would probably substantially reduce the number of ecological field studies necessary to supplement the ecological databases. By reducing the number of ecological field studies, ecological impact assessment and transportation program delivery schedules could be shortened. The real world of databases, models, and GIS is quickly approaching this ideal goal. Already, emergency services use spatial databases to plan and implement civic actions. As these tools are adopted by municipalities and states, they can be used for planning and assessing ecological impacts of roads. For example, standard GIS data on

road networks (for example, TIGER/Line data) could be interfaced with data models (for example, UNETRANS).

The typical ecological database information that would be used in defining the ecological context of the area of potential impacts includes

-

Land uses, including consumptive and nonconsumptive uses

-

Topography

-

Soils

-

Surface waters

-

Groundwater

-

Vegetative cover

-

Plant species population locations, including threatened and endangered plants

-

Animal species population locations, including threatened and endangered animals

-

Important wildlife-movement corridors intersecting transportation corridors

-

Important plant and animal species habitats, including threatened and endangered plants and animals

-

Degraded plant and animal species habitats with restoration potential

Models need to be in place to manipulate these data in ways that are useful to address potential ecological impacts.

A hierarchical approach to assessing ecological condition was developed and tested by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR 2004). This approach begins at the landscape scope and uses the broad-scale perspective to focus the assessment. Such an approach would be very useful to evaluate the ecological impacts of roads.

SUMMARY

This chapter provides a review of current practices in transportation planning and assessment. Large-scale planning processes (such as LRTP) are only required to address air quality issues (such as attainment of standards) and generally do not address other environmental issues. Some states are including environmental information earlier in the planning process, thereby improving the coordination of environmental is-

sues and simplifying the project development process. The science needed to improve early environmental assessment in the planning process is evolving. Models and methods are discussed with examples of some of the more successful approaches. Conceptual analytical approaches are presented and a framework developed. Weaknesses and information gaps needed to bring these concepts to reality are identified. To streamline environmental assessments, three steps must be taken: (1) A checklist addressing potential impacts should be adapted that can be used for rapid assessment. Such a checklist would focus attention on places and issues of greatest concern. (2) A national effort must be made to develop standards for data collection and then to collect appropriate environmental data (both spatial and temporal) across a wide range of scales. These data should be made accessible and available via the internet. (3) A set of models (such as GIS) must be expanded to allow those data to be used in assessments to address scale, feedback, and mixed criteria for environmental protection. Transportation agencies can continue to expand their roles as information brokers and to foster planning forums that integrate environmental planning and assessment across agencies, NGOs, stakeholders, and the public.