E

Late-Life Disability Trends: An Overview of Current Evidence

Vicki A. Freedman*

A fundamental question in population aging research has been whether mortality declines in late life have been accompanied by a compression or an expansion of periods of morbidity and disability1–3. Gruenberg’s theory2 portends pandemic increases in chronic disease and disability, whereas Fries1 suggested that as morbidity onset is postponed and more adults reach the limit to human life, aggregate declines will occur. Manton3 proposed a third perspective, in which declines in mortality yield increases in the prevalence of chronic diseases whose rates of progression are slowed; hence, he predicts declines in the severity of disease and consequent disability even with increases in the prevalence of chronic disease. The competing theories have implications not only for the disability pathways at the end of life but also for trends in cross-sectional snapshots of the prevalence of disability among older Americans.

Numerous studies exploring late-life disability trends in the United States have been published over the last decade or so, sometimes with conflicting results4,5. Central to this debate are critical conceptual distinc-

tions and measurement issues. No studies thus far have tracked trends in late-life participation in society. Instead, most studies measure difficulty or the use of help with daily activities (related either to personal care or to living independently). Recent studies have also highlighted disparities in trends across demographic and socioeconomic groups6–8.

Since these theories of population aging have been proposed, understanding of disability has evolved from a classic medical model, which attributes disability to underlying chronic conditions and impairments, to one that recognizes the fundamentally social and environmental components of disability9,10. As such, recent hypotheses as to the reasons for late-life disability trends have included the influence of chronic disease trends and related medical care; shifts in underlying physical, cognitive, and sensory functioning; changes to the environment, such as technological aids and rehabilitation technologies; and demographic shifts. This paper reviews the most recent evidence on trends in late-life disability in the United States, disparities therein, and current understanding of the reasons for those trends.

TRENDS IN LATE-LIFE DISABILITY

Studies of the 1960s and 1970s suggested that longer life implied worsening health, as measured by increases in self-reported disability and chronic disease11,12. Some have questioned whether these increases were due to changing social forces during the period that made reports of disability more acceptable13.

The evidence for the 1980s and early 1990s was mixed, with Manton and colleagues reporting large declines in disability14,15 and Crimmins and colleagues concluding that there was no clear ongoing trend16. At the request of the National Institute on Aging, the Committee on National Statistics of the National Research Council held a workshop to review the data and methods used to determine trends in disability at older ages17. The workshop report concluded that there had been modest declines in the proportion of older people with limitations in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) but inconsistencies across surveys in trends in activities of daily living (ADLs).

In the decade since that workshop more than a dozen studies have focused on late-life disability trends. A recent review4 highlighted methodological considerations in the comparison of trends in prevalence across surveys and reported findings for a range of outcomes, including physical, cognitive, and sensory limitations as well as ADL and IADL disabilities. The authors found that of the 16 studies identified, 8 unique surveys were analyzed: for the purposes of trend analysis, 2 were rated as good, 4 were rated as fair, 1 was rated as poor, and 1 was rated as mixed (fair or poor,

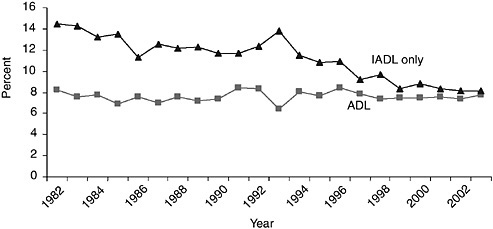

FIGURE E-1 Percentage of the community-based population ages 70 years and older reporting need for help with personal care or only routine care activities, 1982 to 2004. ADL=Needs help with personal care activities such as eating, bathing, dressing, or getting around the home. IADL only=Needs help only with routine needs, such as everyday household chores, doing necessary business, shopping, or getting around for other purposes.

SOURCE: Analysis of the 1982–2004 National Health Interview Survey.

depending on the outcome). Studies rated fair or good consistently showed substantial declines in IADL disability. For example, evidence from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggests that between 1982 and 2004 there has been a 6 percentage point decline in the population ages 70 years and older needing help with only routine care (but not personal care) activities such as shopping, preparing meals, and managing money, sometimes called IADLs (Figure E-1). Subsequent analysis of data from the National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS) suggested that declines in three IADL activities—managing money, shopping for groceries, and doing laundry—were notably large from 1984 to 1999; however, among those reporting an ADL or an IADL disability, the severity of disability increased over time18.

At the time that the review was published, there remained disagreement about whether or not there had been a decline in the proportion of older Americans with difficulty with self-care activities, such as bathing, dressing, toileting, and walking around inside, sometimes called ADLs. The answer was sorted out by a technical working group that analyzed five national surveys conducted from the early 1980s through 200119. The 12-person panel prepared estimates using identical methodologies and investigated sources of the inconsistencies among the population ages 70 years and older. The panel found during the middle and late 1990s consistent declines

on the order of 1 to 2.5 percent per year for two commonly used measures in the disability literature: difficulty with daily activities and help with daily activities. Mixed evidence was found for a third measure: use of help or equipment with daily activities. In comparing findings across surveys, the panel found that time period, definition of disability, treatment of the institutional population, and standardization of results by age were important considerations.

Trends in disability incidence have been much more difficult to characterize, in part because such estimates ideally involve equally spaced and relatively narrow time intervals20. Largely because of data constraints, only three studies to date have focused on trends in disability incidence rates in the United States14,16,21. Using different data and estimation strategies, all three studies show declines in the incidence of disabilities; two of the three suggest that rates of recovery have also declined14,21.

DISPARITIES IN DISABILITY TRENDS

Although the literature on late-life health is relatively large and growing, relatively few studies have focused explicitly on disparities in trends for major demographic and socioeconomic groups. Comparisons across studies are complicated by several factors. First, with few exceptions6–8 statistical tests of disparities in trends have been omitted. Second, in some cases conclusions are dependent on whether the disparity is measured in terms of differences in differences (e.g., Group 1 declined x percentage points more than Group 2) or in relative terms (e.g., the gap between Group 1 and Group 2 doubled from x percent to 2x percent). Third, demographic and socioeconomic groups and measures of disability and functioning vary widely across studies. A recent review4 concluded that evidence on disparities in trends by race, education, sex, and age is limited and mixed, with no consensus yet emerging.

Racial disparities in late-life disability trends have received the most attention in the literature, with inconsistent results. For example, using data from the NLTCS, researchers found increasing racial disparities in the prevalence of chronic ADL or IADL disabilities during the 1980s and diminishing disparities during the 1990s22,23. Three studies of the NHIS (from 1982 to 1996 and from 1982 to 2002)6–8 found no statistically significant changes in the relative gap between minorities and whites; however, there appears to have been a slight narrowing of the absolute size of the gap7.

Reports of disparities in trends by education level have been more consistent. Declines in disability have been larger for those with more than a high school education6–8,24. For example, using data from the 1982 to 2002 NHIS, Schoeni and colleagues6 found that older people with the least education (0 to 8 years) showed virtually no improvement in ADL or IADL

disabilities, whereas those with 16 or more years of education experienced significant declines. Focusing on ADL disabilities, the authors found significant increases for the group with the least education and relatively flat trends for those with 16 or more years of education. Consequently, the socioeconomic gap in disability, which favored the more educated group in 1982, became much larger between 1982 and 2002 both in absolute terms and in relative terms7. However, findings for trends in cognitive functioning showed the reverse pattern with respect to education, with larger improvements among those with less than a high school education25.

Conflicting evidence also exists with respect to disparities by other demographic characteristics. Sex differences in disability and functioning trends have been reported in one instance24 but not in others 7,8,25,26. With respect to age group, findings from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) suggest that the largest absolute improvements in functioning between 1984 and 1993 occurred for the oldest old, but relative improvements were largest for those ages 50 to 64 years. In contrast, focusing on those ages 70 years and older in the NHIS, there appeared to be no statistically significant differences in disability trends by 10-year age groups from 1982 to 19968. This finding appears to be sensitive to model specification, however. Further analysis of the NHIS data finds little change in the simple difference in the need for help with ADLs or IADLs across age groups, but the relative difference increased substantially, resulting in a widening relative gap7. That is, the rate in 1982 was roughly 200 percent higher for people ages 85 years and older than for people ages 70 to 74 years (a 32 percentage point gap), and this increased to nearly 400 percent by 2002.

Other important demographic factors have received little consideration in terms of whether gaps are widening or narrowing. For example, although nativity has been linked to mortality and health outcomes27,28, late-life health trends have not been examined by place of birth. Furthermore, little evidence exists regarding disparities with respect to marital status, occupation, and wealth. Disparities by income quartiles have recently been investigated7, with gaps for the first and fourth income quartiles following a pattern similar to that of education.

EVIDENCE ON WHY LATE-LIFE DISABILITY IS DECLINING

In part because of data limitations, thus far only limited research on possible explanations for these trends in late-life disability has been conducted. Four distinct realms have been explored to date: demographic and socioeconomic shifts; changes in chronic disease and related treatments; trends in underlying physical, cognitive, and sensory functioning; and environmental changes, particularly growth in the use of assistive devices. Re-

search to date suggests that the decline is likely the result of a combination of factors and not any single underlying trend.

The improvement has been attributed in part to the shifting demographic and socioeconomic composition of the elderly population. Notably, the elderly as a group are much better educated today than they were in the mid-1980s; and such a change accounts for a substantial portion—but not all—of the decline in limitations29. The relationship between education and late-life functioning is complex and involves numerous indirect causal pathways. Education, along with other socioeconomic, demographic, and cultural factors, may, for example, influence the risk of disease, injury, and impairment by influencing access to health care throughout life, preventive care, occupational history, social standing (and the consequent stress and environmental exposures), and risk-taking behaviors. More educated people may have a greater ability to marshal resources to optimize their health outcomes and may more easily navigate the health care system, particularly in a managed care setting, in which referrals are needed for specialty care. Moreover, education may affect whether functional deficits result in disability through its influence on assistive device use and the environment. One analysis suggests that impending increases in education levels will continue to contribute to improvements in late-life functioning, albeit at a reduced rate29.

Some evidence also suggests that the extent to which some chronic conditions are expressed in terms of disability may have been ameliorated in recent decades, in particular, for arthritis26 and cardiovascular diseases30, even as the prevalence of many of those conditions has increased in the older population5,24,26. It could be that earlier diagnosis and better management of such conditions has led to lower reported rates of disabilities; however, one investigation of the role of medication use in recent declines among the pre-retirement-age population did not demonstrate a link31, and an investigation of medical procedures for cardiovascular disease provided only weak evidence 30.

A third area of focus has been on trends in underlying physical, cognitive, and sensory functioning. Physical functioning, most often measured with Nagi’s functional limitations (difficulty with body movements such as reaching, bending, and lifting)32, has shown consistently large declines4. For example, one of the only studies of its kind, a comparison of records from white Union Army veterans in 1910 with data for a sample of white men in the 1990s, suggested large declines in functional limitations (difficulty bending and walking)33. Analysis of data from SIPP34 suggested substantial declines in the prevalence of difficulty with climbing stairs, lifting and carrying, and walking three blocks among older Americans between 1984 and 1993. Similar findings were evident from the 1984 and 1994–

1995 Supplements on Aging to the NHIS26 and in additional analysis of the SIPP through 199935.

Evidence regarding trends in cognitive function among the elderly population is not as well developed, but one analysis of the Health and Retirement Study shows that from 1993 to 1998 the proportion of the population age 70 years and older who were severely cognitively impaired declined from 5.8 to 3.8 percent25. More recent analyses through 2000 suggest that some of this improvement may be due to methodological biases36; however, analyses based on the National Long Term Care Survey37–39 also show declines in the prevalence of dementia among older Americans between 1982 and 1999.

The results with respect to sensory functioning are somewhat mixed. Analysis of Union Army records suggests that large declines in blindness and deafness have occurred over the century33. Analysis of SIPP data suggests substantial declines from 1984 to 1993 in the percentage of older Americans with difficulty seeing34 and in the percentage with difficulty seeing or hearing through 199935. Evidence from the Supplements on Aging to NHIS, however, shows that the rates of blindness, deafness, and hearing impairment remained constant between 1984 and 199540.

A final avenue of inquiry has focused on the role of assistive technology in disability trends. Assistive technologies are devices used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities and include both portable aids, such as canes and walkers, and modifications to the environment, such as grab bars and ramps. As first reported a decade ago41, shifts have been occurring in the forms of assistance provided to help people cope with disability in late life. In that study, between 1982 and 1989, equipment use without personal assistance increased among older people with mild chronic impairments and equipment use as a supplement to personal assistance increased among those with severe chronic impairments. During the same period, reliance on personal care without any supplemental equipment declined. The trend toward the use of equipment as a sole form of assistance with daily activities continued through the 1990s18,19,42,43). Estimates from six national surveys conducted over the period spanning 1999 to 2002 suggest that approximately 14 to 18 percent of the U.S. population age 65 or older uses assistive devices—most often, devices for mobility (canes, walkers) and bathing (grab bars, bath seats, railings)44, although socioeconomic gaps that favor more advantaged groups persist 45. A recent study decomposed the declines between 1992 and 2001 in the number of older people receiving help with ADLs into the contributions of demographic shifts, declines in underlying difficulty, and shifts toward the use of assistive technology. In that study, declines in underlying difficulty were most important, but shifts toward the use of assistive technology explained a sub-

stantial portion of the decline, helping to offset increases resulting from population growth and aging43.

On a related note, some researchers have attributed declines in IADL disabilities to the increased availability of modern conveniences. For example, older Americans no longer have to go to the store to shop or to the bank to manage money, and many more have microwave ovens to facilitate cooking18. Moreover, many more seniors are living in supportive living environments that provide assistance with these tasks, such as continuing-care retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and other retirement communities.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE STEPS

In sum, much of the research performed thus far suggests that improvements in late-life functioning and disability have occurred over the past few decades. Declines have been concentrated in activities central to living independently: shopping, managing money, and doing laundry. Much smaller declines in difficulty with and the use of help with self-care activities have been observed. Despite these overall improvements, gaps by race have remained steady and gaps by socioeconomic status have widened.

The causes of these trends are not completely understood, although some results suggest that a combination of factors may be at work. Increases in educational attainment appear to be important, but these increases will not continue at the rates observed over the past two decades. A number of common chronic conditions appear to be less debilitating, and underlying physical functioning has improved. At least some of the declines in the use of help appear to be offset by increases in the use of assistive technologies. Still, there are a number of unanswered questions about the trends. For example, researchers have yet to sort out the role of medical care, the relative contributions of improvements in underlying functioning versus changes in the environment, the relative importance of late-life factors versus factors earlier in life, and changes in perceptions about the meaning of disability. More research in this area is clearly needed.

A number of data challenges will continue to complicate this area of inquiry. Much effort has gone into reconciling differences in trends across national surveys, which vary in their designs and the techniques that they use to measure late-life disability. Recently, attention has been given to ways to incorporate new measurement techniques into national surveys to enhance understanding of late-life trends46. The standardization of disability measures, for example, through the use of vignettes, may promote comparisons across surveys and across groups within surveys. The addition of measures of underlying functioning (assessed through performance measures), the environment (including assistive technologies), and participation

or engagement may facilitate a more refined understanding of the shifts in population-level disability trends. Sorting out the roles of factors earlier in life may require panel surveys that start earlier in life. Inclusion of a standardized core set of disability measures that apply across all ages, as well as life course-specific measures, also may prove useful.

Looking forward, there is debate about the implications of these trends for public and private expenditures18,47-49. Some researchers are optimistic that the declines in rates of late-life disability will ultimately lead to (all else being equal) lower medical costs; others are dubious about whether declines will ultimately lead to savings. Whether declines in late-life disability will continue into the future is unclear, given, for example, the impending increases in rates of obesity50 and related chronic conditions and the slowing increases in educational attainment30.

Indeed, the impending growth of the older population suggests that it will be important to continue to achieve declines in rates of late-life disability. Projections of the size of the older population with disabilities, which depend upon assumptions about mortality and disability rates into the future, suggest that declines in disability rates will need to continue at the rates observed during the 1990s (on average, 1 to 2 percent per year) for this group to remain stable51. Projections that assume much lower rates of decline portend large increases in the number of older people with a disability, from 6 million today to 10 million in 205052. How these population shifts will influence the composition of the population of people with disabilities is unclear and merits further study.

REFERENCES

1. Fries J. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. New England Journal of Medicine 1980;303(3):130–135.

2. Gruenberg EM. Failures of success. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 1977;55(1):3–24.

3. Manton KG. Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 1982;60(2):183–244.

4. Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association 2002;288(24):3137–3146.

5. Crimmins E. Trends in the health of the elderly. Annual Review of Public Health 2004; 25(1):79.

6. Schoeni R, Freedman V, Martin L. Socioeconomic and demographic disparities in trends in old-age disability. University of Michigan Center for Demography of Aging Trends Network Working Paper Series 05-01. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Demography of Aging Trends Network; 2004.

7. Schoeni R, Martin L, Andreski P, Freedman V. Persistent and Growing Socioeconomic Disparities in Disability Among the Elderly: 1982-2002. American Journal of Public Health, 2005;95(11):2065-2070.

8. Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Wallace RB. Persistent, consistent, widespread, and robust? Another look at recent trends in old-age disability. Journals of Gerontology 2001;56(4): S206–S218.

9. Pope AM, Tarlov AR, eds. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991.

10. Brandt EJ, Pope A, eds. Enabling America: Assessing the Role of Rehabilitation Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

11. Colvez A, Blanchet M. Disability trends in the United States population 1966–76: analysis of reported causes. American Journal of Public Health 1981;71(5):464–471.

12. Verbrugge LM. Longer life but worsening health? Trends in health and mortality of middle-aged and older persons. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 1984;62(3):475–519.

13. Waidmann T, Bound J, Schoenbaum M. The illusion of failure: trends in the self-reported health of the U.S. elderly. Milbank Quarterly 1995;73(2):253–287.

14. Manton KG, Corder LS, Stallard E. Estimates of change in chronic disability and institutional incidence and prevalence rates in the U.S. elderly population from the 1982, 1984, and 1989 National Long Term Care Survey. Journals of Gerontology 1993;48(4): S153–S166.

15. Manton KG, Corder L, Stallard E. Chronic disability trends in elderly United States populations: 1982–1994. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 1997;94(6):2593–2598.

16. Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Reynolds SL. Further evidence on recent trends in the prevalence and incidence of disability among older Americans from two sources: the LSOA and the NHIS. Journals of Gerontology 1997;52(2):S59–S71.

17. Freedman VA, Soldo BJ, eds. Trends in Disability at Older Ages: Summary of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994.

18. Spillman BC. Changes in elderly disability rates and the implications for health care utilization and cost. Milbank Quarterly 2004;82(1):157–194.

19. Freedman VA, Crimmins E, Schoeni RF, Spillman BC, Aykan H, Kramarow E, et al. Resolving inconsistencies in trends in old-age disability: report from a technical working group. Demography 2004;41(3):417–441.

20. Wolf DA, Freedman VA, Marcotte JE, Ploutz-Snyder LL. Panel-data bias in estimates of demographic rates: disability dynamics at older ages. In: Workshop on Incomplete Data in Event History Analysis; December 7–8, 2000. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health; 2000.

21. Wolf D, Mendes de Leon C, Glass T. Trends in rates of onset of and recovery from disability at older ages: 1982–1994. In: International Conference on Health Policy Research, October 17-19, 2003, Chicago, IL; 2003.

22. Clark DO. US trends in disability and institutionalization among older blacks and whites. American Journal of Public Health 1997;87(3):438–440.

23. Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2001;98(11):6354–6359.

24. Crimmins E, Saito Y. Change in the prevalence of diseases among older Americans: 1984–1994. Demographic Research 2000;3 Available online. http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol3/9/3-9.pdf. Last accessed: October 27, 2005.

25. Freedman VA, Aykan H, Martin LG. Aggregate changes in severe cognitive impairment among older Americans: 1993 and 1998 . Journals of Gerontology 2001;56(2):S100– S111.

26. Freedman VA, Martin LG. Contribution of chronic conditions to aggregate changes in old-age functioning. American Journal of Public Health 2000;90(11):1755–1760.

27. Angel JL, Buckley CJ, Sakamoto A. Duration or disadvantage? Exploring nativity, ethnicity, and health in midlife. Journal of Gerontology 2000;56(5):S275-284.

28. Elo IT and Preston SH. 1997. Racial and ethnic differences in mortality at older ages. In LG Martin and BJ Soldo, eds. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, pp. 10-42.

29. Freedman VA, Martin LG. The role of education in explaining and forecasting trends in functional limitations among older Americans. Demography 1999;36(4):461–473.

30. Cutler D. Intensive medical technology and the reduction in disability. In: Wise D, ed. Analyses in the Economics of Aging. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2003.

31. Freedman VA, Aykan H. Trends in medication use and functioning before retirement age: are they linked? Health Affairs 2003;22(4):154–162.

32. Nagi SZ. Some conceptual issues in disability and rehabilitation. In: Sussman MB, ed. Sociology and Rehabilitation. Chicago, IL: American Sociological Association; 1966, pp. 100–113.

33. Costa DL. Changing chronic disease rates and long-term declines in functional limitation among older men. Demography 2002;39(1):119–137.

34. Freedman VA, Martin LG. Understanding trends in functional limitations among older Americans. American Journal of Public Health 1998;88(10):1457–1462.

35. Cutler DM. Declining disability among the elderly. Health Affairs 2001;20(6):11–27.

36. Rodgers WL, Ofstedal MB, Herzog AR. Trends in scores on tests of cognitive ability in the elderly U.S. population, 1993–2000. Journals of Gerontology 2003;58(6):S338– S346.

37. Manton KG, Stallard E, Corder L. Changes in morbidity and chronic disability in the U.S. elderly population: evidence from the 1982, 1984, and 1989 National Long Term Care Surveys. Journals of Gerontology 1995;50(4):S194–S204.

38. Manton KG, Stallard E, Corder LS. The dynamics of dimensions of age-related disability 1982 to 1994 in the U.S. elderly population. Journals of Gerontology 1998;53(1): B59–B70.

39. Manton K, Gu X, Ukraintseva S. Declining prevalence of dementia in the US elderly population. Advances in Gerontology 2005;16:30–37.

40. Desai M, Pratt LA, Lentzner H, Robinson KN. Trends in vision and hearing among older Americans. Aging Trends (National Center for Health Statistics) 2001;2:1–8.

41. Manton KG, Corder L, Stallard E. Changes in the use of personal assistance and special equipment from 1982 to 1989: results from the 1982 and 1989 NLTCS. Gerontologist 1993;33(2):168–176.

42. Russell JN, Hendershot GE, LeClere F, Howie LJ, Adler M. Trends and differential use of assistive technology devices: United States, 1994. Advance Data 1997(292):1–9.

43. Freedman V, Agree E, Martin L, Cornman J. Trends in the use of assistive technology and personal care for late-life disability, 1992–2001. The Gerontologist, in press.

44. Cornman JC, Freedman VA, Agree EM. Measurement of assistive device use: implications for estimates of device use and disability in late life. The Gerontologist 2005;45(3): 347–358.

45. Freedman V, Martin L, Cornman J, Agree E, Schoeni R. Trends in assistance with daily activities: racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities persist in the U.S. older population. University of Michigan Center for Demography of Aging Trends Network Working Paper Series 05-02. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Demography of Aging Trends Network; 2004.

46. Freedman VA, Waidmann T. Opportunities for Improving Survey Measures of Late-Life Disability: Workshop Overview. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Service; 2005.

47. Singer BH, Manton KG. The effects of health changes on projections of health service needs for the elderly population of the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 1998;95(26):15618–15622.

48. Cutler DM. The reduction in disability among the elderly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2001;98(12):6546–6547.

49. Chernew, M.E., D.P. Goldman, F. Pan, and B. Shang. 2005. Disability and health care spending among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Affairs Web Exclusive W5:R42-R52.

50. Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T. Increasing obesity rates and disability trends. Health Affairs 2004;23(2):199–205.

51. Waidmann TA, Liu K. Disability trends among elderly persons and implications for the future. Journals of Gerontology 2000;55(5):S298–S307.

52. Tilly J, Goldenson SM, Kasten J. Long-Term Care: Consumers, Providers, and Financing: A Chart Book. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2001.