J

Secondary Conditions and Disability

Margaret A. Turk*

Professionals disagree about the definition of the term secondary condition. Definitions vary (to the extent that they are explicit), and concepts are often confused or misunderstood. The term itself is relatively new. It came on the scene in 1986 through the work of Michael Marge of the National Council on Disability.

Although the term itself was new, the concept that people with disabilities experienced ongoing health problems that were somehow associated with their primary disabling conditions was not new either to them or to the clinicians who treated them. This paper reviews the evolution of the concept of a secondary condition, describes its components, discusses areas of disagreement regarding the definition, and places secondary conditions within the taxonomies of disabilities used in rehabilitation science and clinical practice.

HISTORY

As Heidegger posited (Heidegger, 1964), to name something is to call it into being. After Michael Marge named it, the concept of the “secondary condition” was identified and highlighted in the Institute of Medicine’s

(IOM’s) 1991 report Disability in America (Pope and Tarlov, 1991) and its 1997 report Enabling America (Brandt and Pope, 1997). Both reports defined secondary conditions specifically in terms of physical or mental health problems.

The new concept was embraced, especially by the federal funding agencies, such as the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR), the National Institute for Disability Related Research (NIDRR), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These agencies initially funded research to identify and define secondary conditions and then supported further studies to evaluate interventions that can be used to prevent or modify such conditions. The concept also became a part of the strategic planning cores within the agencies.

Recognizing the potential to improve the prevention of secondary conditions, CDC organized national conferences highlighting their epidemiology as well as preventive and modifying strategies. The conferences promoted discussions that enriched the understanding of secondary conditions. Individuals with disabilities were active participants in the discussions, including discussions of areas for research. The CDC Disability and Health Team initiated a funding stream for research into the secondary conditions of individuals with disabilities, and it also supported statewide disability and health programs and projects. As a result of these CDC-supported initiatives and the strategic plans of NCMRR, NIDRR, and other funding sources, a science base for secondary conditions is developing.

On another front, the American Association of Health and Disability was established. The mission of this professional and advocacy organization is the prevention of additional health complications and secondary conditions in people with disabilities and the encouragement of health promotion and wellness programs that will assist people with disabilities to attain and maintain a positive health status. This national organization promotes interactions and information sharing among consumers, professionals, and agencies regarding secondary conditions and wellness for individuals with disabilities.

KEY DIMENSIONS OF SECONDARY CONDITIONS

No single seminal article has defined and enumerated secondary conditions. Various definitions and lists of conditions have appeared in articles and book chapters, on websites, and in promotional material (Pope and Tarlov, 1991; Lollar, 1994; Brandt and Pope, 1997; Coyle et al., 2000; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000; Simeonsson et al., 2002; Traci et al., 2002; Turk and Weber, 2005). Notwithstanding certain differences, these discussions generally specify some common key dimensions, in particular, that a secondary condition

-

has a causal relationship to the primary condition,

-

may be preventable,

-

may vary in its expression and the timing of its expression,

-

may be modified, and

-

may increase the severity of the primary condition.

The most important and defining of these elements is that a secondary condition is related to a primary condition that is a risk factor for its development. In general, the secondary condition would not exist in the individual but for the presence of the primary condition, although additional factors (such as a lack of appropriate medical care) may contribute to the development of the secondary condition. Examples of common secondary conditions (some of which may also develop in their own right as primary conditions) include

-

pain,

-

osteoporosis,

-

renal insufficiency,

-

chronic lower limb edema,

-

pressure ulcers,

-

obesity,

-

depression, and

-

insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus (in individuals with spinal cord injuries).

As defined by the IOM, a secondary condition involves a physical or mental health problem. Some view the term more broadly to include social problems, such as isolation or relationship problems. This interpretation simply reproduces the general concepts of societal or environmental limitations and dilutes the concept of disability. Secondary conditions defined as health and medical conditions focus the attention on a distinct group of conditions.

Secondary conditions are likely preventable, although the degree of preventive success depends, in part, on many factors, including the underlying mechanisms linking the primary and secondary conditions. Social, personal, and knowledge barriers may impede prevention. Broad social barriers include negative attitudes toward disability; community environments that limit physical access to medical and other services and opportunities; and a lack of funding and other policy support for research, medical services, and additional elements of a successful prevention program. Moreover, individuals with disabilities may have personal characteristics or traits that affect their responsiveness to interventions. Resiliency is one such characteristic that has been recognized as an important variable in successful outcomes.

Certainly, the state of medical science and engineering technology affects the understanding, prevention, and management of secondary conditions. In some cases, research has led to a recognition that a health problem that was once thought to be an independent (or comorbid) condition is actually linked to a disability, for example, diabetes and spinal cord injury, as described by William Bauman in his paper in Appendix M of this workshop report. Such advances in medical knowledge must be disseminated to providers and consumers if it is to be effectively applied to prevent or manage secondary conditions.

In addition, as science or technology progresses, previously expected outcomes may change. Evidence of this comes from the advances in treatment techniques for spasticity that reduce or prevent certain secondary conditions. For example, spasticity and hypertonicity have often been at the base of significant contractures and deformities that limit function, increase the risk for pressure ulcers, and cause pain. Twenty years ago, options for management consisted of only a few medications. Orthopedic surgery was often the only long-standing management option. Over the past 10 years, additional oral medications, botulinum toxin injections, and intrathecal baclofen have changed the incidence and types of anticipated contractures and deformities. Children with cerebral palsy now have access to these interventions, and as they grow and mature, their contractures are often less severe. Surgical interventions are sometimes avoided or delayed.

Secondary conditions vary in the nature and the expression of their manifestations in association with a primary disabling condition. Having a particular disability does not necessarily lead to all secondary conditions associated with that primary disability. For example, not all children with cerebral palsy will have contractures, and some contractures will be more severe than others. Similarly, not all people with spinal cord injuries who have a neurogenic bladder (which results from disruption of the nerve supply to the bladder) will have renal insufficiency. The time of onset of a secondary condition may also vary from person to person. As an example, pain for people with cerebral palsy may become notable in the late teens, early 20s, or late 30s; and onset may be dependent on the individual’s level of function and activity.

Secondary conditions may also be modified by a variety of factors. Anticipatory care may allow early recognition and intervention. However, developmental, personal, and contextual factors may modify problem recognition or treatment strategies. An example is neurogenic bladder and incontinence in individuals with cerebral palsy. Periodic incontinence in a 5-year-old may be ignored or not recognized as a symptom of a secondary condition, whereas such incontinence is not ignored in a 20-year-old who is looking for increased socialization. However, after 20 years of incontinence and possibly recurrent infections, the individual may experience associated

chronic reflux and renal insufficiency. In addition, the interventions fashioned for a 5-year-old are quite different from those fashioned for a 20-year-old. Potentially, earlier recognition of incontinence in an older child or adolescent with cerebral palsy would prompt a timely and full evaluation, the recognition of a neurogenic component, and an intervention to prevent renal abnormalities.

Some secondary conditions, for example, deconditioning, are associated with different types of primary conditions that involve motor limitations. With ongoing investigation into lifelong disabilities and health conditions, more common groupings and risk factors may become more obvious.

The addition of secondary health conditions to a primary condition may increase the level of disability and decrease the quality of life for an individual. Secondary health conditions may require more medical attention, further complicate daily routines, and increase the need for support services. The secondary condition may become the primary medical condition or the individual’s dominant medical problem. Once a secondary condition comes into existence, personal, social and environmental factors may modify the condition or its impact.

TAXONOMIES OF DISABILITY

A variety of taxonomies of disability covering primary, secondary, and other conditions have been used in clinical activities, in scholarly publications and education programs, and in policy proceedings regarding disabilities and their relationship to health and function. The traditional clinical taxonomies used to describe disability employ terms such as primary disabling condition or primary condition, associated conditions, comorbidities, aging, and health. This terminology is used within the narrow context of disability; however, the context can certainly be broadened to include chronic medical conditions as such, for example, diabetes and hypertension. Within a more traditional medical taxonomy of disability, secondary conditions can be distinguished not only from primary conditions but from also comorbidities and other concepts.

Primary conditions are the fundamental sources of disabilities (defined as limitations in the ability to perform certain socially expected roles and tasks). The clinical focus for a disabling condition may change over time. For example, in individuals with spinal cord injuries, neurogenic bladder and the consequent renal insufficiency may become the most disabling conditions to an individual. For someone with motor and cognitive impairments as a result of a traumatic brain injury, the cognitive impairment may come to be seen as a more important source of limitation over time.

Associated conditions are aspects of the pathology of the primary condition; they are expected—if not universal—features or characteristics of

the condition itself. In individuals with cerebral palsy, for example, spasticity is an associated condition, that is, an aspect or part of upper motor neuron impairment; spasticity is not a secondary condition. Other associated conditions generally related to cerebral palsy are seizures and mental retardation; they are aspects of the condition, although not all those with cerebral palsy experience them. Among individuals with spinal cord injuries, associated conditions include neurogenic bladder and bowel and insensate skin. Associated conditions in individuals with traumatic brain injuries with significant motor impairments are typically cognitive or behavioral impairments and spasticity. Again, these are not secondary conditions; they can usually be expected on the basis of the existing pathology.

Comorbidities are health conditions unrelated to the primary condition, in essence, unassociated conditions. There may be pre-existing familial or genetic reasons for these conditions, but there is usually no known causal association with the primary disabling conditions. An example is cancer in an individual with cerebral palsy.

Research may uncover a previously unsuspected link between an apparent comorbidity and a primary disabling condition. The link between insulin-resistant diabetes and spinal cord injury has been identified only during the past 15 years. Understanding the relationships among medical conditions has much to do with the state of the science.

Complications of surgical, pharmaceutical, and other treatments also need to be recognized. In some cases, such treatment complications may be more serious and disabling than the primary or secondary condition being treated.

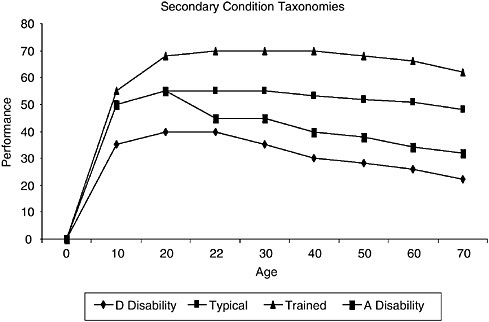

Aging happens regardless of the presence or the absence of disability. Aging is a birth-to-death developmental process and an anticipated decline in organ system function that may be modified but not prevented by genetics or environmental factors. For example, it is scientifically supported that exercise for people at any age can improve motor performance. People with disabilities, however, have a smaller reserve capacity for performance and function that may negatively affect their aging processes (Figure J-1). Exercise, the use of adaptive equipment, and other environmental factors may still enhance performance. Some problems associated with accelerated aging (e.g., early-onset deconditioning) may be viewed as secondary conditions.

In Figure J-1, the small rectangle represents the usual curve of skill attainment to a typical peak performance quotient, followed by a gradual loss of performance over time, if it is assumed that no exercise or focused performance training activity is carried out. The triangle represents a physically trained individual, who will show a higher maximum performance quotient related to exercise and activity and who will maintain a higher level of performance over time, if it is assumed that continued activity and exercise are performed. The large rectangle represents adult-onset disabil-

FIGURE J-1 Conceptual model of aging with different characteristics. D Disability = developmental disability; A Disability = adult-onset disability.

ity. A person with adult-onset disability shows a typical initial attainment of skills followed by a significant drop in function after an acute event, the return of some but not the previous level of performance, and a faster age-related decline in performance over time. Finally, the diamond represents the pattern for someone with a developmental disability who is unable to achieve the typical performance quotient and who shows a faster decline in function. Note the lower performance capacity of the disability-related function and, therefore, the likely more limited reserve capacity for changes in health or the addition of medical conditions.

Health is a continuum, not the absence of impairment or disease. For individuals with disabilities, health status is dependent on the management of the chronic disease process, the maintenance or restoration of function, and the prevention of secondary conditions to the extent possible. In recent decades, the emphasis has increasingly been on health and wellness for people with disabling conditions.

Beyond the traditional clinical perspective on disabilities and other conditions, two models of disability merit attention. Both the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model and the enabling-disabling process—or the IOM model—have been described else-where (World Health Organization, 2001; Pope and Tarlov, 1991; Brandt

and Pope, 1997). Each model defines the changing nature of disability and function relative to modifying factors. Both encompass health as well as medical conditions. Both models attempt to illustrate the entwined nature of function with health, the environment, personal characteristics, and quality of life. Both models also try to represent the continuum of disability. They have proposed useful conceptual distinctions. The IOM model, for example, distinguishes pathology (e.g., nerve damage) from impairment (e.g., muscle atrophy), functional limitation (e.g., the inability to grasp an object), and disability (e.g., the inability to work certain jobs). The ICF model makes a distinction between activities and participation that others have criticized as in need of further clarification or modification (see, e.g., Gale Whiteneck’s paper in Appendix B of this workshop report).

Although neither the ICF nor the IOM graphic model includes secondary conditions as an explicit element, both are consistent with an understanding of primary conditions as a risk factor for secondary conditions. Both are likewise consistent with an understanding that environmental factors and personal choices or traits can affect the development of secondary conditions and the extent to which primary or secondary conditions become disabling. The 1997 version of the IOM model emphasizes quality of life for people with limitations or disabilities as another variable that may be affected by environmental factors and personal characteristics.

CONCLUSION

A secondary condition is a mental or physical health condition that is related to the primary disabling condition or primary health condition. Secondary conditions can be variable in expression, and the timing of their onset is variable. They are likely preventable, although the state of medical science may provide few prevention options for some conditions. Secondary conditions can be modified by many factors. With progression, secondary conditions can increase the severity of the disability or decrease the quality of life.

This understanding of secondary conditions further validates the experiences of people with lifelong disabilities. That is, people with disabilities go through the typical health and aging processes, in addition to idiosyncratic changes related to their particular disabilities.

Although it is an often misunderstood term, secondary condition has been embraced as an important aspect of lifelong disability. The definition has become clearer over time, and there is more agreement regarding the need to limit the term to health conditions. Broadening of the definition beyond health conditions serves to dilute both the concept of secondary conditions and the key elements of disability. Issues of participation, quality of life, and environment are important factors in the classification of

function and disability. Despite disagreements regarding the definition, the national discussion has brought forth consideration of lifelong issues for people with disabilities.

REFERENCES

Brandt EN Jr., Pope AM, eds. 1997. Enabling America: Assessing the Role of Rehabilitation Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Coyle CP, Santiago MC, Shank JW, Ma GX, Boyd R. 2000. Secondary conditions and women with physical disabilities: a descriptive study. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 81:1380–1387.

Heidegger M. 1964. Basic Writings, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

Lollar DJ, ed. 1994. Preventing Secondary Conditions Associated with Spina Bifida or Cerebral Palsy: Proceedings and Recommendations of a Symposium. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC: The Spina Bifida Association of America.

Pope AM, Tarlov AR, eds. 1991. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Simeonsson RJ, McMillen JS, Huntington GS. 2002. Secondary conditions in children with disabilities: spina bifida as a case example. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 8:198–205.

Traci, MA, Seekins T, Szalda-Petree A, Ravesloot C. 2002. Assessing secondary conditions among adults with developmental disabilities: a preliminary study. Mental Retardation 40:119–131.

Turk MA, Weber RJ. 2005. Congenital and childhood-onset disabilities: age-related changes and secondary conditions in mobility impairments. In Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice, 4th ed. DeLisa JA, ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. Healthy People 2010 (Conference Edition, in two volumes). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.