N

Depression as a Secondary Condition in People with Disabilities

Bryan Kemp, Ph.D.*

Depression is one of the world’s most common health problems in the general population, affecting more than 5 percent of all people (Schulberg et al., 1999). In the United States, about 15 percent of the general population will suffer from a major depressive disorder at some time in their life (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993), and to cost the economy $40 billion annually (Robinson et al., 2005). Major depression is especially disabling, but even moderate depression affects daily functioning. Depression has been estimated to be as disabling as congestive heart disease, severe arthritis, and early dementia (Wells et al., 1989).

Depression among people who already have a disability is an especially important and complicated issue. Depression is one of the most common, if not the most common, secondary conditions associated with disability. When it is left untreated, depression can cause inordinate personal suffering, increased disability, additional health problems, and stress in others. It is only recently that there has been any focus on secondary conditions in people who have a disability. The 1991 IOM report Disability in America devoted a chapter to the topic and included depression in the discussion

(Pope and Tarlov, 1991). Previously, most preventive research and policy efforts focused on prevention of the primary impairment, such as a spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, or brain trauma. It is now recognized that it is just as important, if not more important, to address the inordinately high rate of secondary conditions that people with disabilities have.

An entire chapter of the recently published report Healthy People 2010 was related to disability and secondary conditions in people with disabilities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Through this focused attention, the report sought to “promote the health of people with disabilities, prevent secondary conditions, and eliminate disparities between people with and without disabilities in the United States” (p. 3). Of the variety of secondary conditions that occur in people with primary impairments, depression was pointed out as being particularly important. Although there were relatively few data available at the time, that report highlighted the fact that people who have a disability reported having more days of pain, depression, and anxiety and fewer days of vitality during the previous month compared with the rates among people without a disability. That report also emphasized the need for more research, particularly applied research, on the problem of depression among people with disabilities.

A growing focus in the disability community today is the recently noted increase in life expectancy among people with impairments and chronic disabilities, including people with the most severe impairments. For example, life expectancy for a person with a spinal cord injury has increased more than 1,000 percent in the last 40 years (Sasma et al., 1993). Other groups with impairments such as cerebral palsy, polio, rheumatoid arthritis, and Down syndrome are showing similar increases in life expectancy. This aging of people with disabilities has resulted in what appears to be increased secondary conditions as people grow older. Recent research on these conditions (Kemp and Mosqueda, 2004) indicates that as people age with a disability they are at an even higher risk of secondary conditions than they were earlier in their lives. Changes such as a loss of function, increased pain, increased fatigue, and multiple medical problems present new challenges and new stresses to people with disabilities. These new challenges and stresses have a strong likelihood of resulting in difficulties adjusting and a possible increase in the likelihood of depression.

This paper describes what is known about the nature of depression in people with disabilities, its prevalence in groups of people with physical impairments, its possible causes and consequences, the assessment and treatment of depression in people with disabilities, and future research and practice needs. It is clear that better understanding, recognition, and treatment of depression for people with disabilities is an important avenue for improving a range of outcomes that are important to the people with disabilities. For example, it is hard to imagine that people who have a

disability and who are also depressed stand much of a chance of having a good quality of life. It is also likely that people who have a disability and who are depressed are likely to suffer even more health problems. The primary care physicians who encounter people with disabilities are relatively untrained and unsophisticated in dealing with the multiple medical, social, and psychological issues that a person with a disability may have. Improving the understanding of depression and its treatment can help primary care physicians and others better address these needs in people with disabilities.

SECONDARY CONDITIONS AND COMORBIDITIES

Disability in America defines a secondary condition as a new pathology, impairment, functional limitation, or disability that is causally linked to a primary disabling condition (Pope and Tarlov, 1991). In other words, according to the report, the secondary condition would not occur or would be less likely to occur without the existence of the primary condition. Secondary conditions can have either a direct or an indirect causal relationship to the primary impairment. A common direct relationship is one between a pressure sore and a spinal cord injury. Without the spinal cord injury, it is likely that the person would not have developed a pressure sore. Depression is likely an example of a condition with an indirect causal relationship to the primary impairment, because high levels of stress (from the physical environment, interpersonal relations, and health problems) result in an increased risk of hypertension, fatigue, increased disability, and, possibly, depression. Because there is rarely a one-to-one correspondence between a primary impairment and a secondary condition (everyone with the primary impairment does not get the secondary condition), it would perhaps be better to say that the primary impairment increased the risk of a secondary condition through either a direct or an indirect mechanism. Thus, it can be seen that people with disabilities are more vulnerable to certain other conditions. Furthermore, as people with disabilities age, the effects of aging may interact with the disability to further increase vulnerability. Many people with disabilities report that their secondary health conditions are more troublesome—and often are more disabling—than their primary condition.

A comorbidity is a condition that is not related to an individual’s primary impairment. For example, some forms of cancer may occur in people with a disability without being directly or indirectly caused by the primary disability. People who have a disability may still get the flu, although they may not get it at a higher rate than anybody else. From a practical point of view, the presence of a primary impairment, an increased risk of secondary conditions, increased vulnerability because of aging with a disability, and the ordinary

risks of sustaining any comorbid conditions make people with disabilities unique in terms of their health and health care needs. Hence, the prevention of secondary health problems among people with disabilities would do a lot to improve the quality of their lives and, furthermore, would decrease the risks of hospitalization and further disability.

DEPRESSION AS A SECONDARY CONDITION

Depression clearly fits within the definition of a secondary condition. This is especially evident if one focuses on the higher rate of depression among people with disabilities compared with that among the general population. It is unlikely that there is a direct causal relationship between having a disability and developing a depressive disorder because not everyone who has a disability becomes depressed, and as evidence indicates, there is practically no relationship between the severity of the disability and the occurrence of depression (see below).

Depression does appear, however, to be indirectly related to having a disability. The indirect link between depression and disability could be mediated by a variety of mechanisms, but the increased stresses that frequently accompany having a disability are likely. This issue will be further explored below; however, it is clear that having a disability exposes a person to higher rates of economic, environmental, interpersonal, health, and vocational problems than the rates found in the nondisabled population. These increased stresses and the challenges of coping with them appear to contribute to the higher rates of depression among people with disabilities.

Ultimately, depression is a biopsychosocial disorder both in its causes and in its consequences. There are physical aspects to the disorder in terms of central nervous system and autonomic nervous system changes, there are psychological changes in terms of thinking and emotion, and there are social aspects to depression in terms of support from others and the consequences on others. Therefore, having a depressive disorder when one also has a disability may lead to additional problems that will in turn cause more complications. Understanding the mechanisms involved in the development of depression secondary to a disability is essential for both the prevention and the treatment of depression as well as the possibility of reducing other health problems. For example, it is quite common for a person who has a spinal cord injury and who is depressed to not look after himself or herself very well. Consequently, the rates of pressure sores tend to be higher among people who have a depressive disorder. Pressure sores represent one of the most expensive and devastating secondary health problems for people with spinal cord injuries. Yet, it is not possible to fully reduce the rate of pressure sores in this population without also under-

standing the mechanisms by which pressure sores occur through the avenue of a depressive disorder.

DEFINING AND MEASURING DEPRESSION AMONG PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Three major issues complicate research on and clinical interventions for depression among people with disabilities. The first issue is defining depression, the second issue involves the measurement of depression as it applies to people with disabilities, and the third issue concerns the environmental barriers to obtaining proper clinical interventions for people who have a disability and who are depressed.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1995) states that depression is not a single entity but rather a spectrum of disorders that are classified on the basis of the number, severity, type, and progressiveness of the symptoms and their durations and effects on an individual’s function. The central feature of all depressive disorders is an altered mood state that is not normal for that person. This altered mood state may include sadness and melancholia; but it may also include, and frequently does include, irritability or apathy. Other symptoms of depression that need to be present to meet a full diagnosis include those from the categories of cognition, behavior, and physiology. These other symptoms may include changes in appetite or sleep, fatigue or excess subjective pain, decreased energy, or changes in digestion. They may also include thoughts of hopelessness and helplessness or, possibly, even thoughts of suicide. Frequently, the cognitive impairment is also such that the person is incapable of thinking rationally; and reports of memory problems or attention deficits are also frequent. Behavioral symptoms may include not looking after one’s self, not interacting with others in a meaningful or appropriate manner, not following instructions for medical care, and not engaging in meaningful or pleasurable activities. Unfortunately, some of the confusion in the literature and the lack of ability to compare findings result from investigators using the term “depression” to apply to any of the range of disorders across the spectrum.

The diagnosis of depression is ultimately determined after an extensive evaluation. Anything short of that represents some approximation of depression. Instruments that have been developed to assess and measure depression can come close to obtaining true rates of depression if they have been properly designed and validated for the population in question. The population of people with disabilities is unique in terms of the use of instruments to measure depression. The problem is that scales that include a large proportion of physiological symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, and diges-

tive problems) may be assessing the effects of a disability or true health problems rather than depression.

Several screening instruments have been developed to help identify people who may be depressed. They include but are not limited to the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961), the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung, 1965), and the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). All of these scales are used both for nondisabled people and for people with disabilities. At least two screening instruments are especially helpful in identifying depression in groups of people with disabilities. They are the Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire, developed by Kemp and Adams (1995), and the Geriatric Depression Scale, developed by Yesavage and colleagues (1983). Although these two tools were developed from work with a geriatric population, the primary thing that they were trying to compensate for was not age but the presence of the chronic disabling conditions that frequently accompany age. These scales have been used in studies that have included adults with disabilities who were not necessarily part of the geriatric population and have produced many important findings.

It is important to accurately screen for and assess depression in people who have a disability because even relatively minor or moderate levels of depression have been found to have a major impact on health, activities of daily living, and interpersonal relationships among people with disabilities (Hybels et al., 2001). This fact highlights the importance of recognizing and treating all forms of depression, but it also highlights the need to be able to differentiate the different degrees of depression for research purposes. To the extent that studies report either full diagnostic workups or report the results from instruments validated against full workups, they will reflect better data.

The third issue, environmental barriers to proper treatment for people with disabilities who are depressed, relates to how people with disabilities are viewed by clinicians and how they obtain access to services. The major obstacle to the proper treatment of depression, especially major depression, is getting it identified. The high rate of depression among people with disabilities (and other “minority” groups) implies that it is not being properly identified and treated.

PREVALENCE OF DEPRESSION AMONG PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Estimates of the prevalence of depression among people with disabilities vary greatly, depending on the nature of the measurement method, when the measurement was taken relative to the time of onset of the disability, the kind of impairment, and the definition of depression being used.

The overall rate of depression among individuals with disabilities reported in Healthy People 2010 was about 28 percent (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). This finding was based primarily on one question asked in the National Health Interview Survey: “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel so sad that nothing could cheer you up?” That question was then followed up with another question if the person answered positively: “All together, how much did these feelings interfere with your life or activities: a lot, some, a little, or not at all?” The rate of agreement with this statement was 7 percent among people without disabilities.

Other studies have also found rates higher than those cited above. For example, Fuhrer and colleagues (1993) reported a rate of depression of about 40 percent among people with spinal cord injuries. Hughes and colleagues (2001) reported that the rate was even higher among women with spinal cord injuries, and the Consortium for Spinal Cord Injury (1998) established the rate of depression in people with spinal cord injuries to be about 25 percent. Dickens and colleagues (2003) reported that the rate of depression, as measured by standardized methods, was 39 percent among people with rheumatoid arthritis.

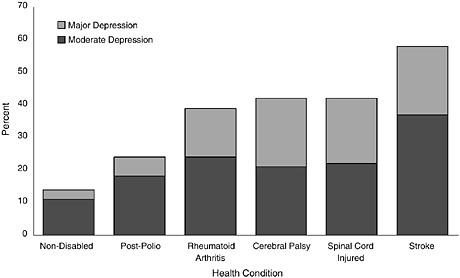

Over the last 10 years, the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Aging with a Disability and Aging with Spinal Cord Injury has conducted studies of depression among people with various impairments to help establish rates of depression. Krause and colleagues (2001) reported on the rate of depression among more than 1,300 people with spinal cord injuries. The overall prevalence was 42 percent. In a sample of people with cerebral palsy, the rate of depression was also found to be 40 percent. Rates of up to 50 percent and higher have been found among people who have had a stroke (Robinson, 2003). These rates include the rates of both moderate and major depression. In each of these cases, approximately half of the cases of depression were severe and major. Figure N-1 displays the rates of moderate and major depression in groups of people with various types of disabling conditions.

Depression among people with disability is as common as disabling arthritis, heart disease, and diabetes combined in the general population. According to the National Center for Health Statistics (1989), the rates of conditions causing activity limitations across all ages in the United States were as follows: arthritis, 12 percent; heart disease, 11 percent; asthma, 4 percent; orthopedic impairments, 21 percent; and diabetes, 3 percent. In 1990, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated the first national colloquium dedicated to the prevention of secondary conditions after a spinal cord injury (Graitcer and Maynard, 1990). This colloquium met at Craig Hospital in Denver, Colorado. The topic of depression was considered to be so important that it was made the number one psychological issue to be addressed as a secondary condition in people with spinal

FIGURE N-1 Depression prevalence among people with different types of disabling conditions.

SOURCES: Robinson (2003), Kemp and Krause (1999), Krause et al. (2001), Dickens and Creed (2001), and Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Aging with a Disability (2003).

cord injuries. Several types of research needs were outlined, including more epidemiological research and research on prevention and care.

In summary, the overall rate of depressive disorders, including both moderate and severe depression, among people with physical disabilities appears to be somewhere between 25 and 50 percent, with approximately half of these cases being major depression. Therefore, one person in four or one person in three who has a primary physical impairment likely also has a depressive disorder. This rate is approximately four times higher than that in the nondisabled population. This figure points to the necessity for regular, routine screening for depression among people with disabilities who consult health providers. However, it fails to recognize the fact that many people who are depressed and who have disabilities do not have a primary health care provider and lack adequate screening for this problem.

CAUSES OF DEPRESSION AMONG PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Understanding the causes of depression in people with disabilities is an important and complex issue for both clinical and research purposes. Clinically, if practitioners believe that depression is caused by the disability, they may be less inclined to provide optimal care because they may believe that

if nothing can be done to cure the disability, then nothing can be done to cure the depression. Therefore, depression may wrongly become viewed as “normal” for people with disability. Research is needed to help identify the true causes of depression so that ways to prevent it and to treat it can better be identified.

Depression does not appear to be a direct result of having a disability. In many studies it has been shown that there is little or no relationship between the severity of impairment or the degree of disability and the rate of depression as measured. For example, McColl and Rosenthal (1994) studied 70 people with spinal cord injuries of various ages and with various durations of disability. They found no relationship between the level of spinal cord injury, scores on the Functional Independence Measure, age, or the duration of the injury and depression. Similarly, in the study by Fuhrer and colleagues (1992), the rates of depression among people with paraplegia were the same as the rates among people with tetraplegia. In the study by Robinson (2003), depression was found to be unrelated to the size or the location of the stroke. In a large-scale study of more than 1,300 people with spinal cord injuries, Krause and colleagues (2001) found no relationship between the level of the spinal cord injury and the rate of depression that was measured. The higher rate of depression in people with disabilities is likely the result of the disability per se. It is therefore more likely that depression relates to disability in an indirect manner.

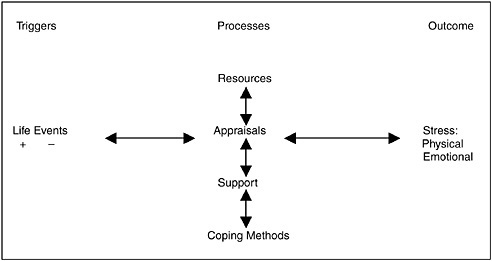

One model that may help explain such a relationship is a general stress and coping model. This kind of model, described by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Haley and colleagues (1987), describes stress and coping as a dynamic interplay involving five primary variables. They argue that the interplay between these five variables helps to determine the outcome from potentially stressful life situations, such as having a disability. These five variables are (1) the number and nature of negative life events that a person faces; (2) the person’s view or appraisal of those events in terms of the perceived degree of threat to his or her future and current well-being; (3) the support that the person receives from other people, both instrumentally and emotionally; (4) the coping methods that the person uses to help deal with these stressors; and (5) the person’s underlying personality. By understanding each of these variables and the interplay among them, research has been able to account for differences in outcomes, such as depression, given the same objective life events, such as a disability.

It has been argued that among people who do not adjust well to stressful life events and who become depressed, problems or deficits in one or more of these areas is likely. For example, those who become depressed are more likely to have a higher number of negative life events over a given period of time than people who are not depressed. Dickens and Creed (2001) studied people with rheumatoid arthritis longitudinally and found

that depression occurred following a deterioration in functional ability. Moreover, deterioration in the activities that the person regarded as especially important (e.g., family and recreation) had the highest correlation with the onset of depression. A 10 percent reduction in valued activities was followed by a 700 percent increase in the rate of depression in the following year. Similarly, people who become depressed are likely to interpret these events in more negative terms than people who do not become depressed (Elliott et al., 1991; Cairns and Baker, 1993). Also, people who become depressed are less likely to have resources in terms of income or support from others to help deal with the stressful life events.

It is likely that differences in these kinds of variables are the source of the differences between rates of depression in nondisabled and disabled individuals. It is clear from the results presented earlier that the level of disability and the severity of impairment are related to the likelihood of depression.

In the study by McColl and Rosenthal (1994), depression was negatively related to social support but not to the level of injury. The statistical correlation (r) between depression and social support was –0.55, indicating a moderate to strong negative relationship. Additionally, people who have a disability have more health problems than people who do not have a disability, and the number of health problems has been found to correlate positively with depression (Kemp et al., 1997; Tate et al., 1994).

Depression is also related to the coping method in people with disabilities. Tate and colleagues (1993) found that people with polio who were depressed had poorer coping methods than people with polio who were not depressed. The same was found for people with multiple sclerosis (Lynch et al., 2001) and spinal cord injuries (Shulz and Decker, 1985). They found that coping methods that are more negative, such as escape-avoidance coping, typically correlates about 0.40 with negative outcomes such as depression in people with spinal cord injuries. People who are less likely to be depressed also appear to have more positive attitudes toward their disabilities (Kemp et al., 1997). Thus, mounting evidence suggests that aspects of stress and coping are predictive of depression. Moreover, because people with disabilities live with the disability long term and experience multiple stressors, they may develop more negative appraisals about what to expect in the future. Certainly, difficulties with obtaining adequate health care, maintaining employment, and economic survival and the ongoing pain and discouragement could lead to more negative appraisals. An important piece of research would be to test this kind of model with people who are depressed and those who are not depressed but who have equivalent disabilities. Figure N-2 presents this general stress and coping model.

The other advantage of a model like this is that it could help direct prevention and intervention efforts toward reducing depression. That is,

FIGURE N-2 A general model of psychological stress and coping.

SOURCES: Adapted from Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Haley et al. (1987).

each of those five variables is something that can, for the most part, be modified and that can be improved to treat depression. For example, if the number of negative life events in a person with a disability is high and comprises such things as health problems, economic problems, and housing problems, then efforts should be directed toward improving those areas of the person’s life. If the difficulty was with the use of inappropriate coping methods, then efforts could be used in counseling to explore other coping methods and try to reduce stress.

CONSEQUENCES OF DEPRESSION FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITY

Depression has multiple consequences for a person with a disability, including effects on longevity, function, community activities, and quality of life. Morris and colleagues (1993) studied over a 10-year period the rates of survival of depressed and nondepressed people who had had a stroke. After 10 years the probability of survival for the nondepressed group was approximately 65 percent, whereas the probability of survival was approximately 30 percent for the depressed group. The difference between the groups increased exponentially each year. The mechanisms involved in the differential survival rates were thought to be more indirect than direct. That is, it was probably not a result of differential suicide rates but, rather, differences in compliance with medications, adherence to health programs,

engagement in exercise, cessation of smoking, and regular follow-up examinations.

Wells and colleagues (1989) concluded that depression and chronic medical conditions had unique and additive effects on patient dysfunctioning. Dickens and Creed (2001) showed that depression added significantly to the health and social problems of people with rheumatoid arthritis, even when they controlled for the degree of disease. Krause and colleagues (2001) found that people with spinal cord injuries who were depressed used more alcohol and had more hospitalizations than people who were not depressed.

In studies at the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Aging with Disability, colleagues and I have monitored people longitudinally over 5-year spans. In one of those studies, we examined changes in activities of daily living among people with disability by status on a depression scale. The results showed that over a 5-year period, activities of daily living decreased nearly twice as much for people who were depressed compared to people who were not depressed. In another study, Kemp and colleagues (2004) assessed community activities and life satisfaction in people with spinal cord injuries who were depressed. Those individuals participated in one-third the number of community activities compared with the number for the nondepressed individuals, and their life satisfaction scores were 40 percent below those for people who were not depressed. In and of itself, the level of spinal cord injury had no effect on these findings.

TREATING DEPRESSION

Although the literature contains scores of articles about depression and disability, relatively few of them concern the treatment of depression. In a recent article, Elliott and Kennedy (2004) reviewed an extensive range of studies in the spinal cord injury literature with the purpose of finding and evaluating the quality of intervention studies directly concerned with the treatment of depression. They found many correlates and concomitants of depressive symptoms among people with spinal cord injuries, but they could find only nine treatment studies that met the criteria for inclusion in their review. Three of the studies were psychological interventions, five studies described antidepressant therapy, and one study reported on the effects of electrical stimulation. Only one of these studies used a randomized assignment to treatment and control groups, but that study excluded people with major depression. Most studies of psychological interventions focused on support groups, counseling, and peer groups. Furthermore, many of the studies focused on inpatients who were undergoing rehabilitation at the same time. Relatively few studies have focused on people living with a disability long term in the community.

King and Kennedy (1999) performed a study that shows both a way to

treat depression in people with disabilities and a way to help prevent it. They used a group approach called the Coping Effectiveness Training (CET) program, which was grounded in the stress and coping model of Lazarus and Folkman (1984). A total of 38 inpatients with spinal cord injuries were divided into treatment and control groups. The treatment group had lower rates of depression at the end of the study. Moreover, the social interaction and reappraisals of the disability were the most important factors in alleviating depression. Such programs as this one could be used to help prevent depression in people with disabilities.

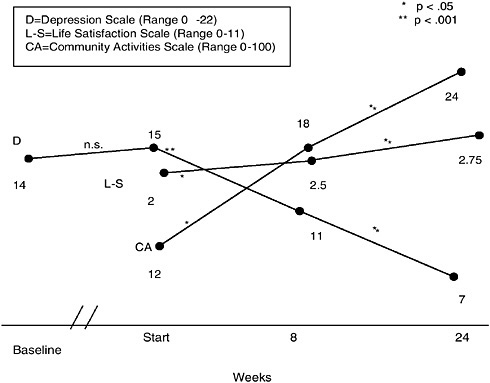

Recently, Kemp and colleagues (2004) studied the effects of treating major depression in people with spinal cord injuries using a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication. They used a quasiexperimental design in which the comparison group declined treatment but was monitored over a similar period of time as those who elected to receive treatment. That study evaluated three outcomes. The first involved changes on a 22-item scale for the measurement of depression. The second was an 11-item life satisfaction scale in which each item was rated on a 4-point scale, with 1 being “mostly dissatisfied” and 4 being “mostly satisfied.” A 16-item community activities checklist that measured the number of times during the last 7 days that a person had engaged in a variety of community activities was also included. Over a 6-month course of treatment, there was a 57 percent reduction in the rate of depressive symptoms among the treated individuals, whereas there was no reduction in symptoms among those who declined treatment. Moreover, approximately half the participants in the treated group were either not depressed or had lower degrees of depression by the end of the treatment. Finally, those who received treatment showed an increase in community activities that corresponded to decreases in depressive symptoms and also showed a 40 percent increase in life satisfaction compared with that at the beginning of the treatment. More studies testing treatment interventions are needed to help deal with this important problem. The results of that study are presented in Figure N-3.

One area of research that is needed should determine whether people with disabilities who are also depressed are recognized, properly assessed, and properly treated by their primary physicians. There is relatively little information on this phenomenon, but it is an area of great concern. Considering the fact that Krause and colleagues (2001) found a 40 percent rate of depression and found that very few people were treated implies that this problem goes relatively unrecognized or untreated in the community. In that study, more than 525 people met the criteria for moderate or major depression, yet none of them was being treated. As the country moves toward a managed care model of the provision of health care, with the short appointment times that are part of that model, it will be even more

FIGURE N-3 Effects of treatment on depression. n.s. = not significant.

SOURCE: Kemp et al. (2004).

important to be able to screen individuals quickly and accurately and to refer them for further assessment and treatment.

NEEDED RESEARCH

Research on depression and disability is needed, particularly in the following areas: (1) determination of whether primary care physicians are accurately identifying people with disabilities who are depressed; (2) determination of whether people who have a disability and are depressed are being adequately treated; (3) testing of the interventions that best help people who are depressed and who have a disability; (4) testing of a stress and coping model in a sample of people with disabilities; (5) assessment of the effects of consumer education and various interventions to help prevent depression, such as the teaching of methods to help people cope with stress; (6) determination of the length of treatment interventions that are optimal for people with disabilities; (7) identification of whether peer counseling is

a good adjunct component to standard care for people with disabilities; (8) identification of strategies to help prevent the occurrence of depression in the population of people at risk who have a disability; (9) further study of the effects of depression on other health problems in people with disabilities; and (10) the development and cross-validation of more instruments for the identification of depression in people with disabilities.

CONCLUSIONS

Depression is a common and serious secondary condition among people with disabilities. The rates of moderate and major depression combined are between 25 and 50 percent across impairment groups. Both moderate and major depression can have serious consequences on health status, functional abilities, longevity, interpersonal relations, and quality of life. It appears likely that the disability and its underlying impairment are not direct causes of depression in people with disabilities. Instead, other factors, such as those involved in a stress and coping model, are likely more important. Issues such as the number and nature of negative life events, social support, coping methods, and one’s outlook and viewpoint about stresses and coping appear to be more important than the disability itself. There are several important issues in studying depression among people with disabilities, including the proper definition of depression, the development and use of instruments that take into account their unique health problems, and finally, the proper treatment of depression by reducing some of the environmental and professional training issues that stand in the way. The evidence to date suggests that when proper treatment is provided, depression can be improved and other outcomes are also improved, such as quality of life and community participation. Research is needed in this area to investigate other avenues of treatment and to help validate the approaches that help the best.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1995). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Beck, A.T., Ward, C.H., Mendelson, M., Moch, J., and Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 53–63.

Cairns, D. and Baker, J. (1993). Adjustment to spinal cord injury: a review of coping styles contributing to the process. Journal of Rehabilitation, 59, 30–33.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Injury. (1998). Depression Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Primary Care Physicians. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America.

Dickens, C. and Creed, F. (2001). The burden of depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis . Rheumatology, 40, 1327–1330.

Dickens, C., Jackson, J., Tomenson, B., Hay, E., and Creed, F. (2003). Association of depression and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosomatics, 44(3), 209–215.

Elliott, T.R. and Kennedy, P. (2004). Treatment of depression following spinal cord injury: an evidenced-based review. Rehabilitation Psychology, 49(2), 134–139.

Elliott, T.R., Godshall, F., Herrick, S., Witty, T., and Spruell, M. (1991). Problem-solving appraisal and psychological adjustment following spinal cord injury. Cognitive Therapy Research, 15, 387–398.

Fuhrer, M.J., Rintala, D.H., Hart, K.A., Clearman, R., and Young, M.E. (1992). Relationship of life satisfaction to impairment, disability, and handicap among persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73, 552–557.

Fuhrer, M.J., Rintala, D.H., Hart, K.A., Clearman, R., and Young, M.E. (1993). Depressive symptomotology in persons with spinal cord injury who reside in the community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 74, 255–260.

Graitcer, P.D. and Maynard, F.M. (1990). Psychosocial secondary disabilities. In P.O. Graitcer and F.M. Maynard (eds.). First Colloquium on Preventing Secondary Disabilities among People with Spinal Cord Injuries. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pp. 71–77.

Haley, W.E., Levine, E.G., Brown, S.L., and Bartolucci, A.A. (1987). Stress, appraisal, coping and social support as predictors of adaptational outcome among dementia caregivers. Psychology of Aging, 2, 323–330.

Hughes, R.B., Swedlund, N., Petersen, N., and Nosek, M.A. (2001). Depression and women with SCI. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 7: 16–24.

Hybels, C.F., Blazer, D.G., and Pieper, C.F. (2001). Toward a threshold for subthreshold depression: an analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community sample. Gerontologist, 41(3), 357–365.

Kemp, B. and Adams, B. (1995). The Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire: a new measure of geriatric depressive disorder. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 8, 162–167.

Kemp, B. and Mosqueda, L. (eds.). (2004). Aging with a Disability: What the Clinician Needs to Know. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kemp, B., Adams, B., and Campbell, M. (1997). Depression and life satisfaction in aging polio survivors versus age matched controls. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78, 187–192.

Kemp, B.J. and Krause, J.S. (1999). Depression and life satisfaction among people ageing with a disability: a comparison of post-polio and spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 21(5/6), 241–249.

Kemp, B.J., Kahan, J.K., Krause, J.S., Adkins, R.H., and Nava, G. (2004). Treatment of major depression in individuals with spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 27, 22–28.

King, C. and Kennedy, P. (1999). Coping effectiveness training for people with spinal cord injury: preliminary results of a controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(Pt.1), 5–14.

Krause, J.S., Kemp, B., and Coker, J. (2001). Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators . Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81, 1099–1109.

Lazarus, R.S. and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Lynch, S.G., Kroeneke, D.C., and Denney, D.R. (2001). The relationship between disability and depression in multiple sclerosis: the role of uncertainty, coping and hope. Multiple Sclerosis, 7, 411–416.

McColl, M.A. and Rosenthal, C. (1994). A model of resource needs of aging spinal cord injured men. Paraplegia, 32, 261–270.

Morris, P.L.P., Robinson, R.G., Andrzejewski, M.S., Samuels, J., and Price, T.R. (1993). Association of depression with 10-year post-stroke mortality. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 124–129.

National Center for Health Statistics. (1989). Questionnaires from the National Health Interview Survey, 1980–84. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 1, No. 24, DHHS Publication (PHS) 90-1302. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Pope, A.M. and Tarlov, A.R. (eds.). (1991). Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Committee on a National Agenda for the Prevention of Disabilities, Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Radloff, L.S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures, 1, 385–401.

Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Aging with a Disability, Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center. (2003). Rates of Depression among Adults with Cerebral Palsy. Unpublished data.

Robinson, R.G. (2003). Post-stroke depression: prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and disease progression. Biology Psychiatry, 54(3), 376–387.

Robinson, W.D., Geske, J.A., Prest, L.A., and Barnacle, R. (2005). Depression treatment in primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 18(2), 79–86.

Sasma, G.P., Patrick, C.H., and Feussner, J.R. (1993). Long-term survival of veterans with traumatic spinal cord injury. Archives of Neurology, 50, 909–913.

Schulberg, H.C., Katon, W.J., Simon, G.E., and Rush, A.J. (1999). Best clinical practice: guidelines for managing major depression in primary medical care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(7), 19–26.

Shulz, R. and Decker, S. (1985). Long-term adjustment to physical disability: the role of social support, perceived control and self-blame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1162–1172.

Tate, D., Kirsch, N., Maynard, F., Peterson, C., Forshheimer, M., Roller, A., and Hansen, N. (1994). Coping with the late effects. Differences between depressed and non-depressed polio survivors. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73, 27–35.

Tate, D.G., Forschheimer, M., Kirsch, N., Maynard, F., and Roller, A. (1993). Prevalence and associated features of depression and psychological distress in polio survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 74, 1056–1060.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. (1993). Depression in Primary Care: Volume 1, Diagnosis and Detection. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5. AHCPR Publication 93-0550. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2001). Healthy People 2010: Disability and Secondary Conditions. Vision for the Decade. Proceedings and recommendations of a symposium, Atlanta, Georgia. December 4–5, 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Wells, K.B., Stewart, A., Hays, R.D., Burnam, A., Rogers, W., Daniels, M., Berry, S., Greenfield, S., and Ware, Jr., J.E. (1989). The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: Results from the medical outcomes study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 262(7)6, 914–919.

Yesavage, J.A, Brink, T.L, Rose, T.L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M.B., and Leirer, V.O. (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37–49.

Zung, W.W.K. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12, 63–70.