O

Promoting Health and Preventing Secondary Conditions Among Adults with Developmental Disabilities

Tom Seekins, Meg Traci, Donna Bainbridge, Kathy Humphries, Nancy Cunningham, Rod Brod, and James Sherman*

Disability is one of the nation’s most significant public health issues (Pope and Tarlov, 1991). For example, Berkowitz and Green (1989) estimate that the annual medical costs for disabilities are as high as $79.3 billion. A major contributor to activity limitations due to impairments is secondary conditions, preventable health problems that occur after the acquisition of a primary impairment (Brandt and Pope, 1997; Marge, 1988; Seekins et al., 1991).

Among the population with disabilities, an estimated 2 million to 4 million people have intellectual or developmental disabilities. This group accounted for 35 percent of all disability years in 1986 (Pope and Tarlov, 1991). Furthermore, mental retardation ranks first among all chronic conditions causing activity limitations among people of all ages (LaPlante, 1989). Arguably, secondary conditions play a significant role in limiting the participation of individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities in community life (Pope, 1992).

Although many adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities live with members of their own family, since the late 1960s community-based services have emerged as the dominant public model for supporting individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Chief among the options now available in each state is a network of group homes and supported living arrangements. Prouty and colleagues (2005) estimated that 420,202 adults with developmental disabilities live in 148,520 of these arrangements nationwide.

In the process of deinstitutionalization and the building of a system of community supports, policy makers emphasized residential and employment options. Health, on the other hand, tended to be equated with medical care; and the responsibility for managing the overall health of this population was assigned to medical providers. As a result, little systematic work that integrates efforts to encourage healthy lifestyles has been found. Frey and colleagues (2001) conducted a literature review to identify intervention programs targeting the top 20 secondary conditions found in a series of studies of this population. Of the more than 2,000 studies that they reviewed, only 25 met the minimum criteria of prevention and empirical evaluation.

Researchers, policy makers, and service providers have developed a wide range of empirically derived programs for the general population; but these efforts typically exclude or ignore the needs of people with disabilities. The Surgeon General of the United States thus called for a significant and systematic effort to address the health and wellness needs of people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (U.S. Surgeon General, 2002). This paper outlines one model for conducting research in this area and briefly summarizes the relevant findings from one series of studies. This approach involves contextually appropriate research based on a surveillance model for a targeted population.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF SECONDARY CONDITIONS

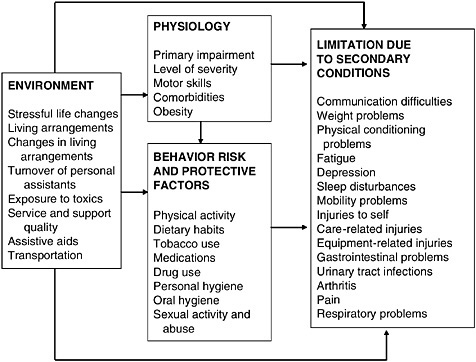

Secondary conditions have been defined as any condition to which a person with a primary diagnosis is more susceptible and may include medical, physical, emotional, family, or community problems (Lollar, 2001). From the perspective of tertiary prevention, it is important to diagnose and treat secondary conditions to limit their impact on an individual. Alternatively, the impact of secondary conditions might be managed. Figure O-1 outlines a conceptual model for understanding secondary conditions. In this model, physiological, environmental, and behavioral risk and protective factors are seen as influencing limitations due to secondary conditions. For example, a change in living arrangements to a less restrictive arrangement may increase limitations due to isolation. Alternatively, the change

FIGURE O-1 Relationship between environmental, physiological, and behavioral risk and protective factors and limitations due to secondary conditions. Changes in risk and protective factors can influence the experience of limitations in participation. The finding of correlations between variables helps identify possible targets for intervention.

may increase the likelihood that an individual may use tobacco and indirectly influence the experience of limitations due to secondary conditions.

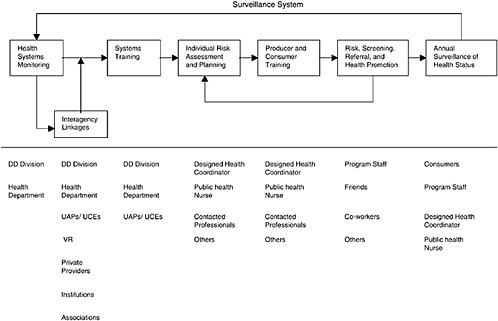

In practice, such a model must be applied to a population living within a context. One way to do this is through a surveillance system that incorporates services directed at identified health problems (Graitcer, 1987). Figure O-2 depicts the major components of such a model for adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in supported arrangements. Starting at the far right, annual assessments of the health of the targeted population of adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in supported living arrangements are conducted, for example, by a designated health coordinator, program staff, and consumers themselves. Data from such assessments are compiled and provided to state program planners. These planners use the data to identify and prioritize targets for intervention. They also mobilize resources to deliver information, training, and support to local service staff. New interventions and treatments are then

integrated into the local service system. The surveillance loop is closed when annual assessments are again conducted. Progress can be assessed and new priorities can be established.

ASSESSING SECONDARY CONDITIONS AND RISK FACTORS

Surprisingly little research has been done to assess secondary conditions among adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Hayden and Kim, 2002; Horowitz et al. 2000; Robertson et al., 2000). In a series of studies supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Montana Developmental Disability Council, we conducted several assessments of limitations due to secondary conditions, the associated risk and protective factors, and the rates of use of medical services.

Assessing Secondary Conditions

As a first key step in developing a systematic, evidence-based approach to preventing and managing secondary conditions among adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in supported arrangements, we developed and validated a secondary conditions surveillance instrument in a series of studies (Traci et al., 2002). The Health and Secondary Conditions Instrument for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (HSCIADD), was designed to measure limitation in participation due to 45 secondary conditions of concern to this population, risk for secondary conditions associated with 3 categories of risk variables (11 lifestyle variables, 4 physiological risk variables, and 21 environmental risk and protective variables), and medical service utilization measures. Limitation due to each secondary condition was reported on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from zero (no limitation) to three (significant/chronic limitation of activities; limits activity 11 or more hours per week).

Four measures were calculated for each secondary condition, including: (1) the percentage of respondents endorsing an item, (2) the prevalence per 1,000 population, (3) the average severity rating of that item, and (4) a problem index. The percentage endorsing an item was calculated by dividing the number of respondents who rated a secondary condition as 1, 2, or 3 by the total number of respondents to the item. Prevalence rate was calculated by dividing the number of persons endorsing an item by the total number of respondents, then multiplying by 1,000. An average severity rating for each secondary condition was calculated by dividing the sum of severity ratings by the number endorsing the item. A problem index was calculated by multiplying the percentage endorsing a secondary condition by the condition’s average severity rating. This fourth measure combines

TABLE O-1 Top Ranked Secondary Conditions

|

Secondary Conditions |

Percent Endorsing |

Prevalence per 1,000 |

Average Severity |

Problem Index |

|

Communication difficulties |

53 |

526 |

1.80 |

95 |

|

Physical conditioning problems |

47 |

466 |

1.49 |

78 |

|

Weight problems |

41 |

411 |

1.62 |

66 |

|

Persistence problems |

42 |

417 |

1.56 |

66 |

|

Personal hygiene problems |

41 |

407 |

1.56 |

64 |

|

Oral health problems |

39 |

390 |

1.64 |

64 |

|

Problems with mobility |

28 |

281 |

1.91 |

54 |

|

Memory problems |

31 |

309 |

1.59 |

49 |

|

Vision problems |

31 |

312 |

1.53 |

47 |

|

Joint and muscle pain |

28 |

277 |

1.65 |

46 |

|

Depression |

29 |

293 |

1.54 |

45 |

|

Fatigue |

30 |

299 |

1.47 |

44 |

|

Balance problems |

26 |

256 |

1.63 |

42 |

|

Sleeping problems |

23 |

234 |

1.52 |

35 |

|

SOURCE: Traci et al. (2002). |

||||

both frequency of occurrence and severity. Thus, the problem index ranks the most severe secondary conditions experienced by the most respondents. Table O-1 presents the top 14 secondary conditions reported in one sample as rank ordered by use of a Problem Index, a calculation used to identify the most significant problem experienced by the most people.

It is noteworthy that a rating of average severity reported by those who experience a problem produces a different order among all items. In this sample, cancer and diabetes (not shown here) were the most limiting secondary conditions but were experienced by far fewer respondents. Thus, they did not rise to the top of this analysis. From a public health perspective, decisions about which secondary conditions should be targeted are influenced by the number of individuals experiencing a condition, the severity of the limitation, the availability of potential interventions, and the cost-benefit of those interventions.

Individual items may reflect underlying groupings. In another study (Bainbridge et al., 2005), we conducted a factor analysis of data from 320 respondents collected in five waves over 12 months. Table O-2 shows the eight multi-item factors and their individual item components. In addition, five single items did not group with any others: gastrointestinal problems, allergies, osteoporosis, hypotension, and pressure sores.

TABLE O-2 Secondary Condition Factors and Items Represented

|

Factor |

Item Components |

|

Hygiene |

Oral health and personal hygiene |

|

Social interaction and access |

Access, mobility, vision, communication |

|

Psychological |

Conditioning, cardiovascular, weight, respiratory, nutrition |

|

Orientation |

Balance, injury, memory |

|

Pain |

Joint and muscle pain, contractures, arthritis |

|

Elimination and digestive |

Bladder, bowel, urinary problems |

|

Equipment |

Failure, injuries to self and others |

|

SOURCE: Bainbridge et al. (2005). |

|

Assessing Risk Factors

This process of surveillance also allows researchers to examine possible linkages between risk and protective factors and the degree of limitation due to secondary conditions. As with secondary conditions, surprisingly little research has been done to assess health risk factors in this population. Havercamp and colleagues (2004) reported that adults with developmental disabilities in North Carolina were more likely to lead sedentary lifestyles and seven times as likely to report inadequate emotional support than adults without disabilities. Robertson and colleagues (2000) found that those living in less restrictive residential settings had poorer diets, were more likely to smoke, and experienced greater rates of obesity.

Behavioral Risk Factors

Seekins and colleagues (2005) collected a range of data on the risk and protective factors experienced by consumers of the Montana service system as part of developing a targeted surveillance system for that population. Consistent with other published findings, they found low levels of physical activity, poor nutrition, mediocre oral hygiene, and high levels of medication use. Several expected correlations appeared, including an increase in problems of physical conditioning with an increase in age, an increase in weight problems as junk food intake increases but a decrease in junk food intake as the intake of fruits and vegetables increases, and decreases in the number of medications as the number of days per week with raising heart rate increases. These are correlations, however, and suggest only possible targets for intervention.

Environmental Risk Factors

The new paradigm of disability places increased emphasis on the contributions of environmental variables to disability (Seelman and Sweeney, 1995; Steinfeld and Danford, 1999). For this population, the organization of the treatment environment plays a critical role in the health and wellness of adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities. These support environments generally involve the provision of personal assistance to the individual with a disability. Personal assistance is specifically identified as a critical contextual component by International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Health–2 (WHO, 1997, p, 235, Code No. e10300) and is provided by people generically referred to as personal assistants. For the many adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in group homes or supported living environments, someone else is primarily responsible for organizing the environment and ensuring that healthy behavior patterns are followed. As such, personal assistants play a significant role in the prevention and management of the secondary conditions experienced by adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Pope, 1992). Motivating direct care providers to consider health as a worthwhile investment is an important and yet largely unaddressed component of health management among adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Unfortunately, data from a number of sources show that consumers experience a high rate of change in personal assistance providers (Felce et al., 1993; Larson and Lakin 1992; Mitchell and Braddock, 1993, 1994; Razza, 1993; Sharrard, 1992). Analyses of pilot data from a sample of 266 adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities found that 66 percent experienced a change in personal assistants over a 24-month period (Traci et al., 1999; Seekins et al., 1999). These individuals had significantly more secondary conditions overall and more injury-related secondary conditions than individuals without a personal assistant change. A 1-year longitudinal study found that limitations due to secondary conditions increased with a change in personal assistants but that higher levels of secondary conditions increased the likelihood that personal assistants would leave (Bainbridge et al., 2005). Stable personal assistance can contribute to the prevention and management of secondary conditions, whereas unstable personal assistance may contribute to the onset and severity of secondary conditions by disrupting the treatment environment at multiple levels (Seekins et al., 1999; Traci et al., 1999). As such, these preliminary data point to stability and the continuity of the personal assistance environment as a key risk and protective factor.

Another critical feature of the treatment environment involves the individual plan. The individual plan, required by law, directs services for consumers and is the blueprint of environmental organization. The individual plan directs the activities of personal assistants. One correlation between

environmental arrangements and health outcomes that suggests an encouraging link is between having an individual plan that addresses a secondary condition and management of that condition. Traci and colleagues (2002) observed that limitations due to secondary conditions addressed by an individual plan were more likely to decline than secondary conditions not addressed by an individual plan.

DEVELOPING CONTEXTUALLY APPROPRIATE INTERVENTIONS

Researchers have established the effectiveness of a wide range of health practices that lead to beneficial outcomes for the general population. Few of these have been explored for use with populations of people with disabilities. A challenge to public health researchers involves the development and evaluation of interventions that can be used to manage or prevent secondary conditions in a support environment with high rates of change of support staff. In addition, the resources available to most public programs are meager. Moreover, staff of these programs must follow many complex regulations governing treatment and personal interactions with residents. As such, interventions must be simple and easy to use, as well as demonstrably cost-effective.

An Example of Oral Health

Bainbridge and colleagues (2004) examined the oral health microenvironments of individuals in supported living arrangements and conducted a pilot project to examine the effectiveness of a simple oral health behavior intervention. Microenvironments consisted of the immediate area—e.g., sink, medicine cabinet, mirror, and toothbrush holder—in which an individual typically keeps his or her oral health equipment and brushes his or her teeth. They found many simple opportunities to arrange the environment to promote hygiene, such as using toothbrush holders that keep individual toothbrushes separate.

They also conducted a pilot test of several strategies to promote brushing behavior. They recruited 12 adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities who received supported living services. Each participant could independently brush his or her own teeth and could understand simple instructions. A dentist examined each potential participant and determined that five individuals were ineligible because of missing teeth or untreated decay. One participant withdrew from the study, and two additional participants were recruited.

Importantly, the researchers piloted two measurement methods to assess the impact on dental health of toothbrushing. A dental hygienist who was unaware of the specific intervention used each measure to screen each

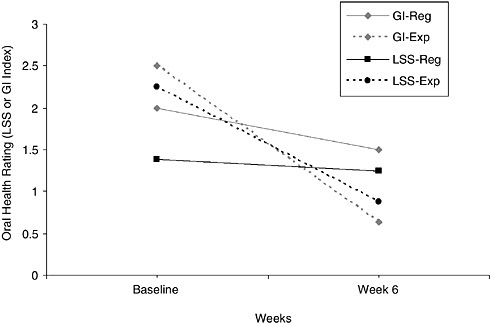

FIGURE O-3 Oral health ratings obtained by using two measures, the Gingivitis Index (GI) and the Lobene Stain Index (LSS), across regular (Reg) and novel (experimental [Exp]) toothbrushes during the baseline and at 6 weeks after the intervention. SOURCE: Bainbridge et al. (2004).

participant before the hygienist cleaned the participant’s teeth. Screening was repeated at the start of the study to establish a comparable baseline and at the end of the pilot study. Participants were divided into three groups, with each group were assigned to use a different experimental brush—a double-headed manual brush, a sonic brush, or a mechanical rotary brush—on the one side of their mouth. As a control, participants used a regular, manual toothbrush on the other side of their mouth across the six weeks of the study. At baseline, the Gingivitis Index for the regular manual brush (control) condition was 2. At week 6, it was 1.5. At baseline, the Gingivitis Index for the experimental brush conditions was 2.5. At week 6, it was 0.63. At baseline, the Lobene Stain Index for the regular manual brush (control) condition was 1.38. At week 6, it was 1.25. At baseline, the Lobene Stain Index for the experimental brush conditions was 2.25. At week 6, it was 0.88. Figure O-3 presents selected data from this pilot test. (Both indexes have a range of 0 to 3 with lower numbers indicating better or more normal oral health.)

These results support the established findings that routine brushing reduces plaque, gingivitis, and debris. Furthermore, the investigators found

that maintenance of a routine brushing schedule required minimal support time and cost.

Comprehensive Programs of Health Promotion

Although the development and validation of targeted interventions that demonstrate health improvement is a valuable endeavor, it is also important to explore methods for the systematic delivery of such interventions consistently and on a broad scale. Such models might focus on organizing the support environment and limiting reliance on staff. The program should fit seamlessly into the existing operations of service provider and be relatively easy to implement and manage. It should also be flexible and allow the framing of action steps related to any of the 467 objectives outlined in Health People 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Finally, it should anticipate the emergence of new service models in which consumers live in settings providing increased independence and decreased levels of supervision.

Currently, we are developing The Wellness Club, a contextually appropriate intervention that is designed to serve as a mechanism that can be used to consistently address health and wellness issues within supported living arrangements. The Wellness Club is the system that we have designed for planning, implementing, and evaluating these action steps for Americans with developmental disabilities. It is a model system for organizing resources and supports to prevent and manage secondary conditions by building and maintaining healthy lifestyles. It embeds wellness education and the management of secondary conditions into a model of individual services based on principles and procedures of choice and applied behavior analysis. The Wellness Club consists of general wellness education and materials for providers and consumers, global assessments for individual planning, specific functional assessments for the design of an individual treatment plan, standard mechanisms for prompting and reinforcing healthy lifestyle behaviors, self-monitoring, and evaluation procedures. Such programs promote lifestyle changes through social engagement and making healthy living fun.

CONCLUSIONS

The new paradigm of disability places emphasis on the contribution of the environment to the outcomes of a disability. The national network of supported living arrangements provides an excellent example of the importance of environmental variables to health. More research should be conducted to obtain an understanding of the role of personal assistants in promoting and maintaining the health of the population with intellectual or

developmental disabilities. In addition, we need to better understand how individualized plans can incorporate health and wellness goals.

A substantial body of research has demonstrated the health benefits of a wide range of lifestyle practices. The findings of this research provide one example an empirically derived health promotion strategy for adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in supported living arrangements. Importantly, such demonstrations must show how they may be easily incorporated into a system with many responsibilities and high rates of staff turnover.

Finally, a relatively small proportion of adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities live in supported living arrangements. Researchers should address the needs of this population who still live with their parents into late adulthood. Similarly, researchers and educators should explore models for introducing health promotion and lifestyle management into the education process for students with disabilities.

REFERENCES

Bainbridge, D.B., Traci, M.A., Seekins, T., Peterson, S., Huckebe, R., and Millar, S. (2004). Oral Health Program for Adults with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities: Results of a Pilot Study. Missoula: Rural Institute on Disabilities, The University of Montana.

Bainbridge, D.B., Traci, M.A., Seekins, T., Brod, R., and Senninger, S. (2005). The Effects of Direct Service Staff Stability-Instability on the Health of Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Supported Environments in Montana: A Final Report. Missoula: Rural Institute on Disabilities, The University of Montana.

Berkowitz, M., and Green, C. (1989). Disability expenditures. American Rehabilitation, 159, 7–29.

Brandt, E.N., and Pope, A.M. (eds.) (1997). Disability and the environment. In Enabling America: Assessing the Role of Rehabilitation Science and Engineering (pp. 147–169). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Felce, D., Lowe, K., and Beswick, J. (1993). Staff turnover in ordinary housing services for people with severe or profound mental handicaps. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research, 37(2), 143–152.

Frey, L., Szalda-Petree, A., Traci, M.A., and Seekins, T. (2001). Prevention of secondary health conditions in adults with developmental disabilities: a review of the literature. Disability and Rehabilitation, 23(9), 361–369.

Graitcer, P. (1987). The development of state and local injury surveillance systems. Journal of Safety Research, 18, 191–198.

Havercamp, S.M., Scandlin, D., and Roth, M. (2004). Health disparities among adults with developmental disabilities, adults with other disabilities, and adults not reporting disability in North Carolina. Public Health Reports, 119, 418–426.

Hayden, M.G., and Kim, S.H. (2002). Health Status, Health Care Utilization Patterns, and Health Care Outcomes of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities: A Review of the Literature (p. 1391). Policy Research Brief. Minneapolis: Institute on Community Integration, University of Minnesota.

Horowitz, S.M., Kerker, B.D., Owens, P.L., and Zigler, E. (2000). The health status and needs of individuals with mental retardation. New Haven, CT: Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University School of Medicine and Department of Psychology. [Online.] http://www.specialolympics.org/NR/rdonlyres/e5lq5czkjv5vwulp5lx5tmny4mcwhyj5vq6euizrooqcaekeuvmkg75fd6wnj62nhlsprlb7tg4gwqtu4xffauxzsge/healthstatus_needs.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2005.

LaPlante, M.P. (1989). Disability in Basic Life Activities across the Life Span. Disability Statistics Report 1. San Francisco: Institute for Health and Aging, University of California.

Larson, S.A., and Lakin, K.C. (1992). Direct-care staff stability in a national sample of small group homes. Mental Retardation, 30, 12–22.

Lollar, D.J. (2001). Public health trends in disability: past, present, and future. In: Albrecht, G.L., Seelman, K.D., Bury, M. (eds.), Handbook of Disability Studies (pp. 754–771). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Marge, M. (1988). Health promotion for persons with disabilities: moving beyond rehabilitation. American Journal of Health Promotion, 2, 29–44.

Mitchell, D., and Braddock, D. (1993). Compensation and turnover of direct-care staff in developmental disabilities residential facilities in the United States. I. Wages and benefits. Mental Retardation, 31, 429–437.

Mitchell, D., and Braddock, D. (1994). Compensation and turnover of direct-care staff in developmental disabilities residential facilities in the United States. II. Turnover. Mental Retardation, 32, 34–42.

Pope, A.M. (1992). Preventing secondary conditions. Mental Retardation, 30, 347–354.

Pope, A.M., and Tarlov, A.R. (eds.) (1991). Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Prouty, R.W., Smith, G., and Lakin, K.C. (2005) Residential Services for Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Status and Trends Through 2004. Minneapolis: Research and Training Center on Community Living, Institute on Community Integration.

Razza, N.J. (1993). Determinants of direct-care staff turnover in group homes for individuals with mental retardation. Mental Retardation, 31, 284–291.

Robertson, J, Emerson, E., Gregary, N., Hatton, C., Rutner, S., Kessissoglou, S., and Hallam, A. (2000). Lifestyle related risk factors for poor health in residential settings for people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 21, 469–486.

Seekins, T., Smith, N., McCleary, T., Clay, J., and Walsh, J. (1991). Secondary disability prevention: involving consumers in the development of policy and program options. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 1(3), 21–35.

Seekins, T., Traci, M.A., and Szalda-Petree, A. (1999). Preventing and managing secondary conditions experienced by people with disabilities: roles for personal assistants providers. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 22, 259–269.

Seekins, T., Traci, M.A., Bainbridge, D. B., and Humphries, K. (2005). Toward secondary conditions risk appraisal for adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities. In W. Nehring (ed.), Health Promotion with Persons with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Seelman, K., and Sweeney, S. (1995). The changing universe of disability. American Rehabilitation, Autumn-Winter, 2–13.

Sharrard, H. E. (1992). Feeling the strain: job stress and satisfaction of direct-care staff in the mental handicap service. The British Journal of Mental Subnormality, 38, 32–38.

Steinfeld, E., and Danford, G.S. (1999). Enabling Environments: Measuring the Impact of Environment on Disability and Rehabilitation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Traci, M.A., Szalda-Petree, A.C., and Seninger, S. (1999). Turnover of personal assistants and the incidence of injury among adults with developmental disabilities. Rural Disability and Rehabilitation Research Progress Report #3. Missoula, MT: Research and Training Center on Rural Rehabilitation Services, University of Montana.

Traci, M.A., Seekins, T., Szalda-Petree, A.C., and Ravesloot, C.H. (2002). Assessing secondary conditions among adults with developmental disabilities: a preliminary study. Mental Retardation 40, 119–131.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Surgeon General (2002). Closing the Gap: A National Blueprint to Improve the Health of Persons with Mental Retardation. Washington, DC: U.S. Surgeon General.

WHO (World Health Organization). (1997). ICIDH-2: International Classification of Impairments, Activities and Participation [sic]. Geneva: WHO.