6

Description of Epidemiologic Studies Included in Evidentiary Dataset

COHORT STUDIES

Reports Included in the Evaluation of Cancer Risks

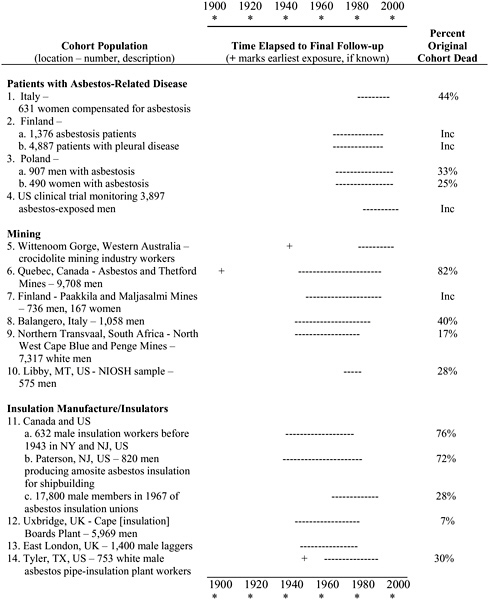

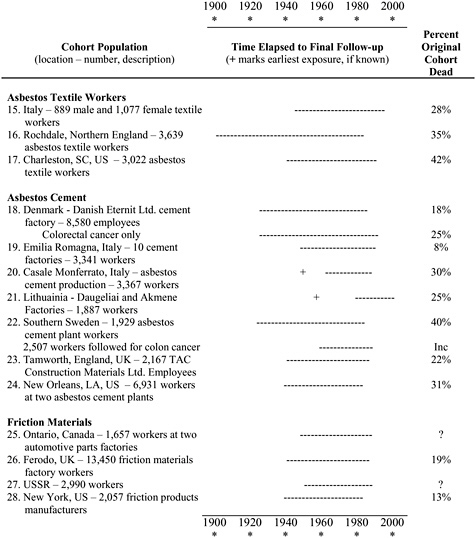

Table 6.1 delineates the 40 main cohort populations that passed the committee’s primary eligibility criteria and were found to contain usable information on the risk of cancer at one or more of the sites of interest for this review. Some of the cohorts contained subpopulations (such as men and women) whose results were reported separately. Furthermore, tracking of multiple aspects of the health over decades in many of the cohort populations has resulted in numerous published analyses. Among these, this committee was interested in the most complete, and thus usually the most recent, citation addressing cancer incidence or mortality. Specific citations contributing information to this review are given in the rightmost column. In some instances, different publications provided the most complete information on a given subpopulation or cancer site, so more than one citation may have served as a source of evidence on a single main cohort population. Table B.1 in Appendix B provides more detail about the overall history (such as updates and the nature of asbestos to which the subjects were exposed) of each studied population on a citation-specific basis; boldface indicates particular citations that were the source of evidence abstracted for any of the cancer sites under consideration.

Table 6.2 presents results observed in the informative cohort populations with regard to the recognized asbestos-related health effects: asbestosis, mesothelioma, and lung cancer. Those findings provide a rough indication

TABLE 6.1 Description of Cohorts Informative for Selected Cancers

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Results for Selected Cancers (ICD range specified; mortality unless otherwise noted) |

Source Citation |

|||||

|

Pharynx |

Larynx |

Esophagus |

Stomach |

Colon |

Rectum |

||

|

Patients with Asbestos-Related Disease |

|

||||||

|

|

161 |

|

151 |

153 |

154 |

Germani et al. (1999) |

|

|

161? |

150? |

151? |

153? |

154? |

Karjalainen et al. (1999) |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Szeszenia-Dabrowska et al. (2002) |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

153-154 ? |

Aliyu et al. (2005) |

||||

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Results for Selected Cancers (ICD range specified; mortality unless otherwise noted) |

Source Citation |

|||||

|

Pharynx |

Larynx |

Esophagus |

Stomach |

Colon |

Rectum |

||

|

Mining |

|||||||

|

140-149, 160 ? |

161 ? |

150 ? |

151 ? |

|

152-154 ? |

Armstrong et al. (1988) [mortality to 1980] |

|

|

C09.0-C14.8 |

C32.0-C32.9 |

C15.0-C15.9 |

C16.0-C16.9 |

|

C18.0-C20.9 |

Reid et al. (2004) [incidence 1979–2000] |

|

|

161 |

150 |

151 |

|

152-154 |

McDonald et al. (1993) [through 1976–1988] |

|

Mines |

|

161 |

#150 |

151 |

|

#152-154 |

Liddell et al. (1997) [through 1950−1992] |

|

|

161 ? |

150 ? |

151 ? |

|

153-154 ? |

Meurman et al. (1994) |

|

140-149 ? |

161 |

|

150-151 ? |

|

152-154 ? |

Piolatto et al. (1990) |

|

140-149 |

161 |

#150 |

#151 |

#153 |

#154 |

Sluis-Cremer et al. (1992) |

|

|

|

|

151 |

|

|

Amandus and Wheeler (1987) |

|

Insulation Manufacture/Insulators (Laggers) |

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

140-149, 161 ? |

150 ? |

151 ? |

|

153-154 ? |

Selikoff et al. (1979) [through 1976] |

|

|

140-149, 161 ? |

150 ? |

151 ? |

|

153-154 ? |

Seidman et al. (1986) |

|

146 ? |

161 |

150 |

151 |

|

153-154 |

Selikoff and Seidman (1991) [through 1986] |

|

|

|

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Acheson et al. (1984) |

|

140-148 |

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Berry et al. (2000) |

|

140-149 |

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Levin et al. (1998) |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Results for Selected Cancers (ICD range specified; mortality unless otherwise noted) |

Source Citation |

|||||

|

Pharynx |

Larynx |

Esophagus |

Stomach |

Colon |

Rectum |

||

|

Asbestos Textile Workers |

|

||||||

|

140-149 |

161 |

|

151 |

|

152-154, 159.0 |

Pira et al. (2005) |

|

|

161 ? |

150 ? |

151 ? |

|

153-154 ? |

Peto et al. (1985) |

|

|

161 |

|

151 |

|

|

Dement et al. (1994) [through 1990] |

|

Asbestos Cement |

|

||||||

|

140-148 |

161 |

|

151 |

153 |

154 |

Raffn et al. (1989) [incidence through 1984] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

153 |

154 |

Raffn et al. (1996) [incidence through 1990] |

|

140-149 ? |

161 |

|

|

|

|

Giaroli et al. (1994) |

|

|

161 ? |

|

151 ? |

|

153-154 ? |

Botta et al. (1991) |

|

|

161 |

|

151 |

|

153-154 |

Smailyte et al. (2004a) [incidence] |

|

|

|

|

150-152 |

|

153-154 |

Albin et al. (1990) [mortality through1986] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

153 |

154 |

Jakobsson et al.(1994) [incidencethrough 1989] |

|

|

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Gardner et al. (1986) |

|

140-149 |

161 |

150 |

151 |

|

153-154 |

Hughes et al. (1987) |

|

Friction Materials |

|

||||||

|

|

161 |

|

|

|

|

Finkelstein (1989a) |

|

|

161 |

|

|

|

|

Berry (1994) |

|

|

|

|

151 ? |

|

|

Kogan et al. (1993) |

|

140-149 ? |

161 |

|

|

|

|

Parnes (1990) |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Results for Selected Cancers (ICD range specified; mortality unless otherwise noted) |

Source Citation |

|||||

|

Pharynx |

Larynx |

Esophagus |

Stomach |

Colon |

Rectum |

||

|

Generic “Asbestos Workers” |

|

||||||

|

|

#161 ? |

#150 ? |

151 ? |

|

#153-154 ? |

Zhu and Wang (1993) |

|

|

|

|

151 ? |

|

|

Pang et al. (1997) |

|

|

|

|

150-151 |

|

153-154 |

Woitowitz et al. (1986) |

|

140-148 |

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Berry et al. (2000) |

|

|

|

|

151 |

|

|

Acheson et al. (1982) |

|

|

|

150 ? |

151 ? |

153 ? |

154 ? |

Hodgson and Jones (1986) |

|

140-148 |

161 |

150 |

151 |

153 |

154 |

Enterline et al. (1987) |

TABLE 6.2 Rates of Accepted Asbestos-Related Health Outcomes in Cohorts Informative for Selected Cancers

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Accepted Asbestos-Related Health Outcomes (number observed, RR, 95% CI) |

Source Citation |

||

|

Asbestosis |

Lung Cancer |

Mesothelioma |

||

|

Patients with Asbestos-Related Disease |

|

|||

|

all |

16, 4.8 (2.7-7.8) |

14, 64.0 (35.0-107) |

Germani et al. (1999) |

|

|

|||

|

all |

6 F, 19.80 (7.3-43.1) |

1 F, 95.7 (2.4-533) |

Karjalainen et al. (1999) |

|

|

0 F |

0 F |

|

|

|

|||

|

all |

|

|

Szeszenia-Dabrowska et al. (2002) |

|

all |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aliyu et al. (2005) |

|

Mining |

|

|||

Western Australia —6,505 men |

|

91 M, 1.60 (1.31-1.97) |

32 |

Armstrong et al. (1988) [mortality through 1980] Berry et al. (2004) [incidence through2000] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

646, 1.37 |

38 |

Liddell et al. (1997) [1950-1992] |

|||

|

|

76 M, 2.88 (2.27-3.60); 1 F, 2.22 (0.06-12.4) |

4 M, 45.6 (12.2-115) |

Meurman et al. (1994) |

|||

|

16 |

22, 1.1 |

2, 6.7 |

Piolatto et al. (1990) |

|||

|

1 |

63, 1.72 (1.32-2.21) |

16 |

Sluis-Cremer et al. (1992) |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

20, 2.23 (1.36-3.45) |

Included with lung |

Amandus andWheeler (1987) |

|||

|

|

21 |

2 |

McDonald et al. (1986) |

|||

|

Insulation Manufacture/Insulators (Laggers) |

|

||||||

|

427 |

1,168, 4.35, p<0.001 |

458 |

Selikoff and Seidman (1991) |

|||

|

|

57, 2.0 |

5 |

Acheson et al. (1984) |

|||

|

|

38, 3.67 |

13 |

Berry et al. (2000) |

|||

|

3 |

35, 2.77 (1.93-3.85) |

4, 28.8 (7.9-73.8) |

Levin et al. (1998) |

|||

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Accepted Asbestos-Related Health Outcomes (number observed, RR, 95% CI) |

Source Citation |

||

|

Asbestosis |

Lung Cancer |

Mesothelioma |

||

|

Asbestos Textile Workers |

|

|||

|

38 |

76, 2.82 (2.22-3.54) |

37, 27.8 (19.6-38.6) |

Pira et al. (2005) |

|

7 |

132, 1.31, p<0.01 |

11 |

Peto et al. (1985) |

|

|

4, 1.55 (0.53-3.55) |

2 |

Dement et al. (1994) |

|

Asbestos Cement |

|

|||

|

|

162, 1.80 (1.54-2.10) |

10, 5.46 (2.62-10.1) |

Raffn et al. (1989) [incidence through 1984] |

|

|

|

1.63 (1.26-2.08) |

|

Raffn et al. (1996) [incidence through 1990] |

|

|

33, 1.24 (0.91-1.66) |

6, 4.11 |

Giaroli et al. (1994) |

|

85 M; 4 F |

110 M, 2.71 (2.23-3.27); 7 F, 3.96 (1.59-8.16) |

|

Botta et al. (1991) |

|

|

29 M, 0.9 (0.7-1.3); 1 F, 0.7 (0.1-4.6) |

0 M; 1 F, 20.1 (2.9-142) |

Smailyte et al. (2004a) |

|

|

35, 1.8 (0.90-3.7) |

13, 7.2 (0.97-54) |

Albin et al. (1990) |

|

|

34 M, 0.9 (0.6-1.3); 6 F, 1.4 (0.5-3.1) |

1 M; 0 F |

Gardner et al. (1986) |

|

|

154, 1.34 |

1 |

Hughes et al. (1987) |

|

Friction Materials |

|

|||

|

|

11, 1.40 |

Included with lung |

Finkelstein (1989a) |

|

|

|

|

Berry (1994) |

|

|

2, 0.11 |

|

Kogan et al. (1993) |

|

|

15, 0.95 |

|

Parnes (1990) |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Accepted Asbestos-Related Health Outcomes (number observed, RR, 95% CI) |

Source Citation |

||

|

Asbestosis |

Lung Cancer |

Mesothelioma |

||

|

Generic “Asbestos Workers” |

|

|||

|

|

67, 4.2 |

|

Zhu and Wang (1993) |

|

|

3 M, 5.1; 6 F, 6.8 |

|

Pang et al. (1997) |

|

|

a. 26, 1.70 b. 12, 4.62 |

a. 6 b. 6 |

Woitowitz et al. (1986) |

|

|

b. 157, 2.55 c. 37, 7.46 |

b. 60 c. 25 |

Berry et al. (2000) |

|

|

22, 2.00 |

3 |

Acheson et al. (1982) |

|

11 |

157, 1.30 |

34 |

Hodgson and Jones (1986) |

|

22 |

77, 2.71 |

Included with lung |

Enterline et al. (1987) |

|

Other Occupations with Substantial Asbestos Exposure |

|

|||

|

|

393, 1.27 (1.13-1.42) |

8 |

Finkelstein and Verma (2004) |

|

|

227, 1.18 (1.03-1.35) for all 7,775 shipyard workers |

1, 1.13—in a machinist, not pipe fitter |

Tola et al. (1988) [incidence] |

|

|

26, 1.24 (0.87-1.72) [90%CI] |

5, 13.27, (5.23-27.9) [90%CI] |

Battista et al. (1999) |

|

18, 46.6 (27.6-73.6) |

298, 1.77 (1.57-1.98) |

60, 5.24, (4.00-6.74) |

Puntoni et al. (2001) |

|

|

11, 1.12 (0.56-2.0) |

4 |

Sanden and Jarvholm (1987) |

of asbestos exposure and of how informative each of the cohorts might be expected to be in contributing evidence to the committee’s evaluation of asbestos’s role in others cancers.

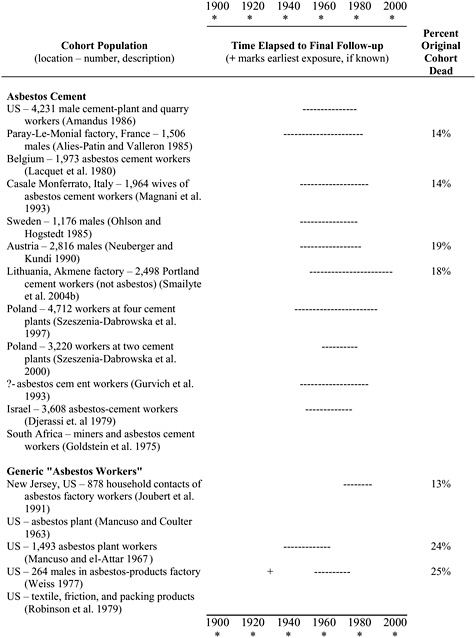

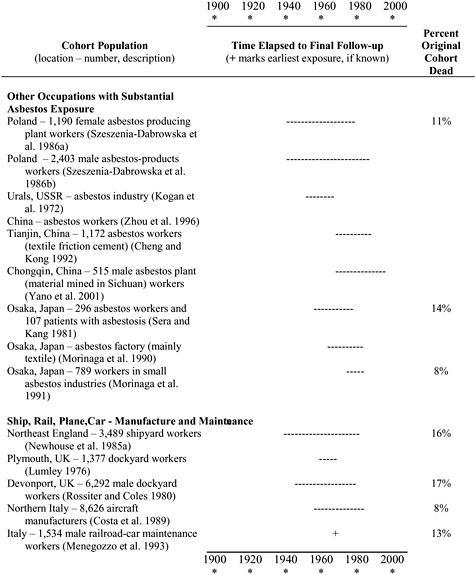

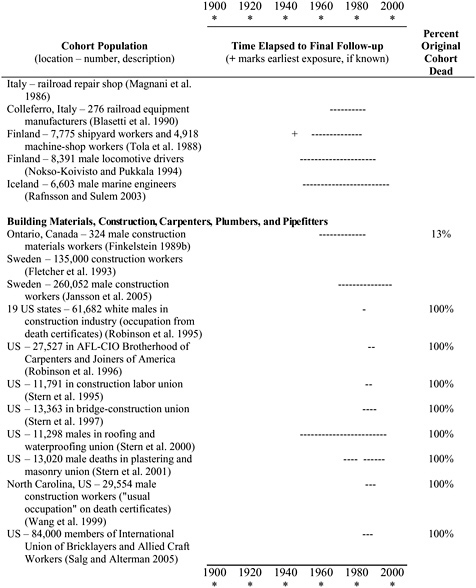

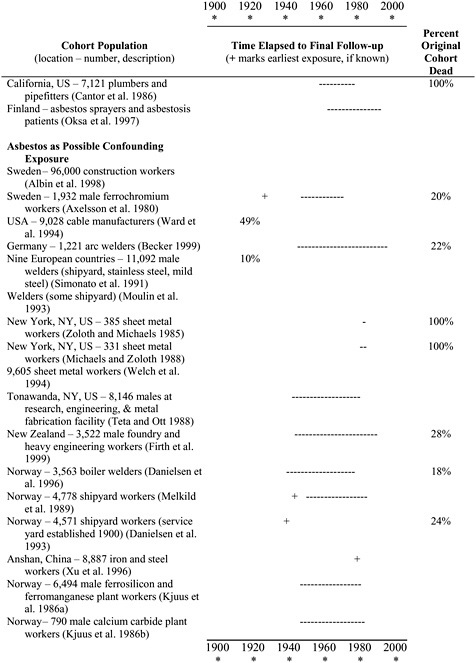

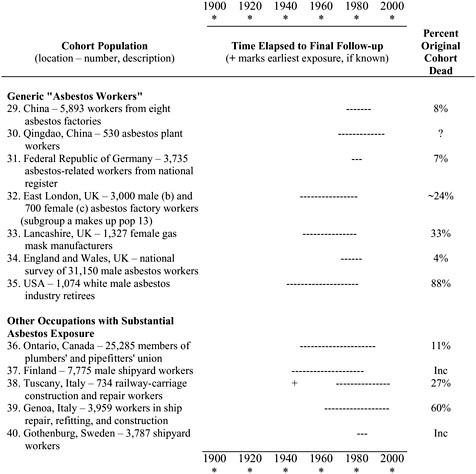

For the cohorts that provided information on at least one of the selected cancer sites, Figure 6.1 gives a graphic indication of the period when exposure was occurring and of the length of the most recent (most complete) follow-up of the vital status of the cohort members. The figure also includes the percentage of the original cohort members found to have died as an index of a cohort’s “maturity,” which suggests how much additional information might be garnered if follow-up were extended for the cohort.

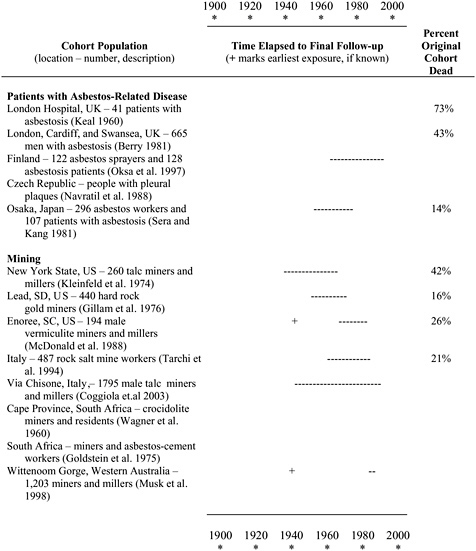

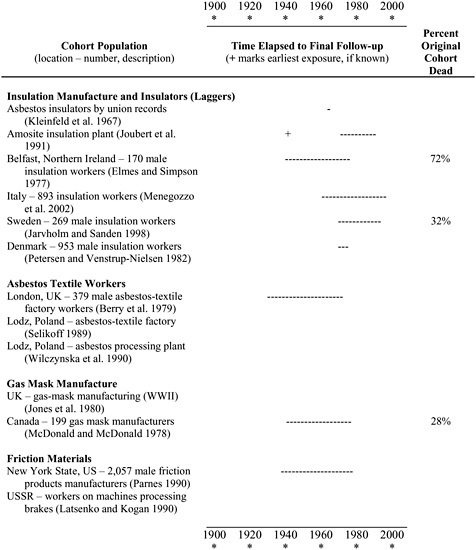

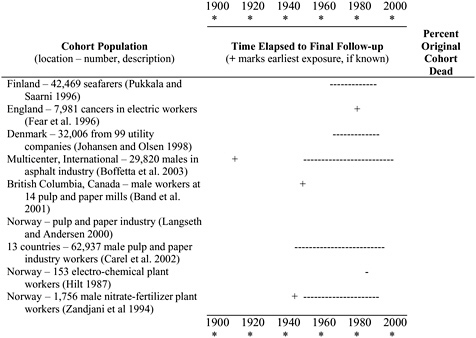

Figure 6.2 presents an analogous picture for the roughly six dozen asbestos-exposed cohorts that the committee screened for the selected cancers but found no usable information. The most recent citation related to cancer outcomes is specified. The considerably greater number of cohorts in the uninformative category gives an indication of the extent to which research has focused on reporting respiratory outcomes of asbestos exposure.

The cohort studies retained for the evidentiary dataset addressed defined occupational cohorts in specific asbestos industries (such as mining and milling, cement, textile, and friction products), in less clearly specified industries (such as “asbestos factory”), or employed in certain occupations with documented asbestos exposures (such as insulators). Some of the cohort studies derived qualitative categories of asbestos exposure based on individual work history or clinical factors (such as presence of pleural plaques). Quantitative exposure assessments to enable dose estimation were available only for a small percentage of the studies.

We summarized findings from reports of cohort studies of asbestos-exposed workers in which cancer-risk data were available on at least one of the specific cancers of interest as delineated in Table 6.1. The main cohort populations were made up of workers employed in asbestos mining (6); manufacturing and use of insulation (3), textiles (4), cement (7), friction materials (4), and various other asbestos products, such as gas masks (7); and in other occupations with substantial asbestos exposure (5). The most recent report of a cohort study was selected if there had been repeated follow-ups; this was the case for studies of the London East End factory (Berry et al. 2000), US textile workers (Dement et al. 1994), Quebec miners (Liddell et al. 1997, McDonald et al. 1993), and North American insulation workers (Selikoff and Seidman 1991); see Table B.1 for a listing of the citations that were superseded.

We also included in our review three studies of cohorts of patients with asbestosis or nonmalignant pleural disease who had worked in any of numerous unspecified industries and occupations (Germani et al. 1999, Karjalainen et al. 1999, Szeszenia-Dabrowska et al. 2002) under the assumption that there was a high likelihood of exposure of cohort members

to asbestos. Additionally, we included a cohort of asbestos-exposed people who had been monitored in a clinical trial (Aliyu et al. 2005).

We reviewed but did not include cancer-risk data from studies of cohorts of workers in several industries in which modest asbestos exposure occurred in conjunction with major exposure to other toxic agents, such as a refinery and petrochemical plant (Tsai et al. 1996), rubber industry (Straif et al. 1999), and a nitric acid factory (Hilt et al. 1991).

Health Outcome Data

In most of the cohort studies reviewed, cancer mortality was the health outcome analyzed. There were very few cancer incidence studies; the excep-

tions were studies of Swedish insulation workers (Sanden and Jarvholm 1987) and of cement workers in Sweden (Jakobsson et al. 1994) and Denmark (Raffn et al. 1989, 1996). Consequently, disease occurrence may have been under-ascertained in some cohort studies, especially for pharyngeal, laryngeal, and colorectal cancers, which generally have higher survival rates than esophageal and stomach cancers. Although under-ascertainment would tend to diminish the power of these studies, it is unlikely to have created an important systematic bias because it is reasonable to assume that the extent of disease ascertainment was unrelated to asbestos exposure.

Cancer mortality information in the cohort studies was derived predominantly from death certificates. Death-certificate data were augmented with clinical information (such as an autopsy reports or medical-chart reviews) in studies of North American insulation workers (Selikoff and Sediman 1991) and German workers in various industries (Woitowitz and Seidman 1986) to derive “best-evidence” risk estimates. We reported those “best-evidence” relative risks (RRs) in our summary of findings, acknowledging that they may over-estimate risks somewhat because comparison rates, typically from national populations, were limited to death-certificate data.

To evaluate the individual risks of cancer of the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, colon, or rectum, one would want to consider together reported statistics for International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes 146-148, 161, 150, 151, 153, and 154, respectively, but in practice many publications grouped their findings into broader ranges. As explained in Chapter 2, the committee determined that the only coarser groupings of sites that could be considered meaningful were pharynx with oral cavity, larynx with epilarynx (portions of the oropharynx specified as ICD codes 146.4, 146.5, and 148.2), and rectum with colon.

In addition to studies reporting on the selected cancers in acceptable categories, the assembled literature on asbestos-exposed cohorts included some papers presenting data only for “gastrointestinal” or “abdominal” cancers. Such groupings make the findings for esophagus, stomach, colon, and rectum indistinguishable, and also potentially included cancers of the pancreas, liver, gall bladder, and small intestine, which are not relevant to this review. Although the desired site-specific findings are not recoverable, for completeness, Table 6.3 presents results for aggregated gastrointestinal cancers from those cohort studies that provided their findings only in such form. The information gathered in this table could not be used by the committee in reaching its conclusions.

Data on the specific cancers of interest to the committee (cancers of the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, colon, or rectum) came from 40 major cohort populations. None of the cohort studies included data on histologic type of cancer; although many of the 36 case-control studies (discussed in the following section) involved histologic confirmation of cancer diagnosis, their results were not generally presented by histologic type. Furthermore, few of the studies provided data specific for cancer subsites. As a result, the committee did not attempt to draw conclusions at a more refined level than the groupings specified in its charge.

Exposure Assessment

Considerable attention has been given to possible differences among fiber types in their potential to cause cancer, especially in the context of examining mesothelioma risk. Recent reviews suggests that, rather than having no carcinogenic activity, chrysotile has a generally lesser degree of potency than amphibole fibers and that the various types of amphibole fiber have differing potency in the extent of their biological activity (Britton 2002, IPCS 1998, Roggli 2006, Roggli et al. 1997, Suzuki et al. 2005).

In this review, we noted predominant fiber types where information was provided. Table 6.4 provides an alphabetical listing of the informative citations and the corresponding cohort populations, which will facilitate cross-referencing from the citations listed in the summary figures of site-

TABLE 6.3 Cohort—Study Results on Various Groupings of Gastrointestinal Cancers (Grouped)

|

Source Citation |

Location |

Industry Type or Occupation |

Fiber Type (primary) |

Population |

Overall Cohort Results No. cases RR (95% CI) |

Highest Exposed Results No. cases RR (95% CI) |

Comments |

|

McDonald et al. (1986) |

Libby, Montana, US (1986) Overlap with NIOSH cohort in Amandus and Wheeler (1987)? |

Mining |

Vermiculite |

406 men |

7 SMR = 0.88 (no CI or p-value) |

5 SMR = 1.11 (no CI or p-value) |

ICD8 150-159; highest exposed: ≥20 yrs since first exposure |

|

Sluis-Cremer et al. (1992) |

South Africa |

Mining |

Amosite, crocidolite |

7,317 men |

36 SMR = 0.88 (0.62-1.22) |

— |

ICD9 150-159 digestive + peritoneum |

|

Thomas et al. (1982) |

Wales |

Cement |

Chrysotile, some crocidolite |

1,592 men |

18 SMR = 0.92 (no CI or p-value) 6 |

SMR = 1.20 (no CI or p-value) |

ICD8 151-154; highest exposed: employed 1935-36 |

|

Finkelstein (1984) |

Ontario, Canada |

Cement |

Chrysotile? |

535 men |

8 SMR = 2.85 (no CI or p-value) |

2 (or 1 best evidence) SMR = 5.00 (no CI or p-value) |

ICD? 150-154; highest exposed: 30-34 yrs since first exposure |

|

Giaroli et al. (1994) |

Italy |

Cement |

Chrysotile, crocidolite |

3,341 |

28 SMR = 0.91 (0.65-1.25) |

— |

Digestive tract + peritoneum (1) |

|

Hughes and Weill (1991) |

New Orleans, Louisiana, US |

Cement |

?? |

839 men |

6 SMR = 0.65 (no CI or p-value) |

— |

ICD8 150-159 |

|

McDonald et al. (1983) |

South Carolina, US Overlap with cohort population in Dement et al. (1994) |

Textile |

Chrysotile |

2,543 men |

26 SMR = 1.52 (no CI or p-value) |

0 SMR = 0 (irregular d-r trend, increaseuntil last stratum, then 0 cases) |

ICD? 150-159; highest exposed: ≥80 mppcfy |

|

McDonald et al. (1982a) |

Pennsylvania US |

Textile, friction products |

Chrysotile |

1,200 men + women |

54 SMR = 1.13 (no CI or p-value) |

7 SMR = 2.37 (no CI or p-value) RR = 2.85 from nested c-c analysis (no CI or p-value) |

ICD? 150-159; highest exposed: ≥80 mppcfy |

|

McDonald et al. (1984) |

Connecticut, US |

Friction materials |

Chrysotile |

3,641 men |

59 SMR = 1.14 (no CI or p-value) |

3 SMR = 1.27 (no CI or p-value) |

ICD? 150-159; highest exposed: ≥80 mppcfy |

|

Newhouse et al. (1985b) vs Berry et al. (1985) |

England |

Friction materials |

Chrysotile |

8,404 men 4,167 women |

men: 156 SMR = 0.93 (0.81-1.06) women: 46 SMR = 0.98 (0.74-1.22) |

men: 56 SMR = 0.89 (0.70-1.09) women: 13 SMR = 1.23 (0.73-1.96) |

highest exposed: ≥10 yrs employed, ≥20 yrs since first exposure |

|

Source Citation |

Location |

Industry Type or Occupation |

Fiber Type (primary) |

Population |

Overall Cohort Results No. cases RR (95% CI) |

Highest Exposed Results No. cases RR (95% CI) |

Comments |

|

Finkelstein (1989b) |

Ontario, Canada |

Friction materials |

Chrysotile |

1,194 men |

6 SMR = 0.81 (no CI or p-value) |

5 SMR = 0.92 (no CI or p-value) |

ICD9 150-159; data presented for ≥20 yr since first exposure; highest exposure: ≥20 yr employed |

|

Enterline and Kendrick (1967) |

US |

Various Building, friction, textile products |

??? |

21,755 men |

building products: 36 SMR = 0.89 (no CI or p-value) friction materials: 36 SMR = 1.19 (no CI or p-value) textile: 11 SMR = 1.46 (no CI or p-value) |

— |

ICD7 150-159; cohort age 15-64 years, multiple companies; cotton-mill worker comparison group |

TABLE 6.4 Asbestos Types Associated with Exposures of Cohorts Informative for Selected Cancers (alphabetical order by author to correspond with plots in Chapters 7-11)

|

Source Citation |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Type(s) of Asbestos Comprising Exposure |

|||||

|

Serpentine Chrysotile |

Amphibole |

Mixed (M) or Not Stated (?) |

||||||

|

Crocidolite |

Amosite |

Anthophyllite |

Tremolite-Actinolite |

|||||

|

Acheson et al. (1982) |

33. |

Lancashire, UK—gas mask manufacture |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Acheson et al. (1984) |

12. |

Uxbridge, UK—Cape [insulation] Boards Plant |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Aliyu et al. (2005) |

4. |

US clinical trial monitoring asbestos-exposed men |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

Amandus and Wheeler (1987) |

10. |

Libby, MT, US—NIOSH sample—miners |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Armstrong et al. (1988) |

5a. |

Wittenoom Gorge, Western Australia—miners [deaths before 1980] |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Battista et al. (1999) |

38. |

Tuscany, Italy—railway-carriage construction and repair |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Berry (1994) |

26. |

Ferodo, UK—friction materials factory |

X mainly |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Berry et al. |

13. |

East London, UK—1400 male laggers (2000) |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Berry et al. (2000) |

32. |

East London, UK—3,000 male and 700 female asbestos factory workers |

X mainly |

X |

X |

|

|

Botta et al. (1991) |

20. |

Casale Monferrato, Italy—asbestos cement production |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Dement et al. (1994) |

17. |

Charleston, SC, US—asbestos textile workers |

X |

|

|

|

|

Enterline et al. (1987) |

35. |

USA—asbestos industry retirees |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Finkelstein (1989a) |

25. |

Ontario, Canada—two automotive parts factories |

|

|

|

? |

|

Finkelstein and Verma (2004) |

36. |

Ontario, Canada—members of plumbers’ and pipefitters’ union |

|

|

|

? |

|

Gardner et al. (1986) |

23. |

Tamworth, England, UK—TAC Construction Materials Ltd. |

X |

|

|

|

|

Germani et al. (1999) |

1. |

Italy—631 women compensated for asbestosis |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Giaroli et al. (1994) |

19. |

Emilia Romagna, Italy—10 cement factories |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Hodgson and Jones (1986) |

34. |

England and Wales, UK—national survey of asbestos workers |

|

|

|

M |

|

Hughes et al. (1987) |

24. |

New Orleans, LA, US—workers at two asbestos cement plants |

X mainly |

X |

X |

|

|

Jakobsson et al. (1994) |

22. |

Southern Sweden—asbestos cement plant |

X mainly |

X |

X |

|

|

Source Citation |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Type(s) of Asbestos Comprising Exposure |

|||||

|

Serpentine Chrysotile |

Amphibole |

Mixed (M) or Not Stated (?) |

||||||

|

Crocidolite |

Amosite |

Anthophyllite |

Tremolite-Actinolite |

|||||

|

Karjalainen et al. (1999) |

2. |

Finland— a. 1,376 asbestosis patients b. 4,887 patients with pleural disease |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

Kogan et al. (1993) |

27. |

USSR |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Levin et al. (1998) |

14. |

Tyler, TX, US—753 white male asbestos pipe-insulation plant workers |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Liddell et al.(1997) and McDonald et al. (1993) |

6. |

Quebec, Canada—Asbestos and Thetford Mines—miners |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meurman et al. (1994) |

7. |

Finland—Paakkila and Maljasalmi Mines—miners |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Pang et al. (1997) |

30. |

Qingdao, China—asbestos plant |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parnes (1990) |

28. |

New York, USA—friction products manufacture |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peto et al. (1985) |

16. |

Rochdale, Northern England |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Piolatto et al. (1990) |

8. |

Balangero, Italy—miners |

X |

|

|

|

|

Pira et al. (2005) |

15. |

Italy—889 male and 1,077 female textile workers |

|

|

|

? |

|

Puntoni et al. (2001) |

39. |

Genoa, Italy—ship repair, refitting, and construction |

|

|

|

? |

|

Raffn et al. (1989) |

18. |

Denmark—Danish Eternit Ltd. cement factory |

X mainly |

X |

X |

|

|

Reid et al. (2004) |

5b. |

Wittenoom Gorge, Western Australia—miners [incidence 1979-2000] |

|

X |

|

|

|

Sanden and Jarvholm (1987) |

40. |

Gothenburg, Sweden—shipyard workers |

X mainly |

X |

X |

|

|

Seidman et al. (1986) |

11. |

b. Paterson, NJ, US—820 men producing insulation for shipbuilding |

|

|

X |

|

|

Selikoff et al. (1979) |

11. |

a. 632 male insulation workers before 1943 in NY/NJ |

|

|

|

? |

|

Selikoff and Seidman (1991) |

11. |

Canada/USA c. 17,800 male members of asbestos insulation unions in 1967 |

|

|

|

? |

|

Sluis-Cremer et al. (1992) |

9. |

Northern Transvaal, South Africa—North West Cape Blue and Penge Mines—miners |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Smailyte et al. (2004a) |

21. |

Lithuainia—Daugeliai and Akmene Factories |

X |

|

|

|

|

Source Citation |

|

Cohort Population (location—number, description) |

Type(s) of Asbestos Comprising Exposure |

|||||

|

Serpentine Chrysotile |

Amphibole |

Mixed (M) or Not Stated (?) |

||||||

|

Crocidolite |

Amosite |

Anthophyllite |

Tremolite-Actinolite |

|||||

|

Szeszenia-Dabrowska et al. (2002) |

3. |

Poland— a. 907 men with asbestosis b.490 women with asbestosis |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

Tola et al. (1988) |

37. |

Finland—7,775 male shipyard workers |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

Woitowitz et al. (1986) |

31. |

Federal Republic of Germany—asbestos-related workers from national register |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

Zhu and Wang (1993) |

29. |

China—eight asbestos factories |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: Column 1 of Tables 6.1-6.2 reordered by source citation. |

||||||||

specific Chapters 7-11. Table 6.4 also specifies the types of asbestos to which the cohorts were exposed. The contents of Table 6.4, however, demonstrate for workers in these cohorts that exposures have often been mixed, with one type of asbestos commonly being contaminated by others and with some industrial processes intentionally involving mixtures. If inferences could only be drawn from studies of exposure to a single type of asbestos, the database would be inadequate to draw any conclusions. There was only one informative cohort population for exposure to anthophyllite and one for exposure to tremolite or actinolite; two separate populations were said to have been exposed to amosite exclusively; two populations divided only by time from Wittenoom Gorge were the only ones considered as exposed only to crocidolite; while 10 of the 45 citations reported only exposure to serpentine chrysotile. For the remainder, the researchers stated the exposure was mixed or did not attempt to characterize it beyond “asbestos.” Predictably, chrysotile was the most frequently mentioned type. There were too few studies of single forms of asbestos to support separate evaluations according to fiber type and inclusion of studies with exposure to mixed or unknown fiber types would have generated fiber-type-specific associations subject to considerable uncertainty; consequently the committee did not characterize associations by fiber type.

The type and quantity of data available for assessing asbestos exposures varied considerably among studies. The committee partitioned these methods of exposure assessment into categories of relative quality. Although the underlying data may have been gathered with a variety of methods having different sensitivities, the highest category of relative quality was quantitative estimates of the concentration of asbestos fibers based on workplace measurements. The optimal, but rarely available, exposure metric was deemed to be cumulative exposure, in which concentrations measured with reliable industrial-hygiene techniques would be combined with each individual’s job history to obtain years of exposure to concentrations expressed as mppcf (million particles per cubic foot) or f/cm3 (fibers per cubic centimeter) of air. Such estimates of cumulative exposure were derived only in studies of South Carolina textile workers (Dement et al. 1994; McDonald et al. 1982, 1983), Quebec chrysotile miners (McDonald and McDonald 1997), Italian chrysotile miners (Rubino et al. 1979), Wittenoom Gorge, Australia crocidolite miners (Reid et al. 2004), and Louisiana cement-factory workers (Hughes et al. 1987).

A second tier of exposure assessment quality consisted of more qualitative approaches to deriving scales for dose-response analyses. In numerous studies, less specific data, such as duration of employment in the industry or occupation or ordinal rankings of jobs (for example, “heavy” and “light”), served as surrogates in dose estimation.

In the remaining studies, absence of any sort of detailed exposure data

from which gradients could be defined limited risk estimation to contrasts between exposed and non-exposed (“any vs none” in the meta-analyses), typically formulated as risk comparisons between an entire cohort and the general population. In practice, even studies in which quantitative exposure data had been gathered seldom reported dose-response gradients for the selected cancers of interest in this review. Lung cancer, which is far more common, was the principal focus in those studies; perhaps concerns about limitations of statistical power prevented partitioning the small observed number of these other cancers into exposure categories. Consequently, many of the cohorts in which exposure had been extensively assessed contributed no more to this evaluation for the selected cancers than an “any vs none” comparison with the general population. The dearth of quantitative dose-response data is clearly a limitation of the literature on the selected cancers.

As reflected in the results tables in Appendix D, for each cohort study, we transcribed estimates of RR for the entire cohort compared with the general population (a contrast of any exposure vs no exposure) and, when exposure gradients were defined, for the subgroup in the most extreme exposure category (a contrast of high exposure vs no exposure).

CASE-CONTROL STUDIES

Reports Included in the Evaluation of Cancer Risks

The committee’s search for relevant case-control studies first screened the literature for investigations of the selected cancers that included occupation among the risk factors considered and then retained those that actually assessed and reported asbestos exposure. Table 6.5 summarizes the 36 case-control studies that were found to be informative for any of the cancer sites of interest, ordered by the quality of the method of exposure assessment used (as described below). Details about the design characteristics of the studies can be found in Table C.1 in Appendix C.

Although multiple publications may result from a single case-control investigation, in general they do not have as complex histories as do cohort studies carried out over several decades. This chapter’s presentation of the case-control studies evaluated in a single one-page table, in contrast to the several multipage tables and figures shown concerning the cohort studies, is not a reflection of the relative importance of these two study designs in the committee’s evaluation. Both designs have their merits, and the results from both are complementary.

The case-control method has several specific strengths in comparison to the cohort study design, some of which may be particularly advantageous for studies of asbestos. First, case ascertainment can be accompanied by pathological review of cancers, thus validating the cancer type and allowing

TABLE 6.5 Summary of Case-Control Studies Addressing Selected Cancers

|

Quality of Exposure Characterization |

Type of Cancer Investigated |

||||

|

Pharyngeal |

Laryngeal |

Esophageal |

Stomach |

Colorectal |

|

|

High |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 unique citations |

Berrino et al. (2003) |

Berrino et al. (2003) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dietz et al. (2004) |

|

|

Dumas et al. (2000) |

|

|

Gustavsson et al. (1998) |

Gustavsson et al. (1998) |

Gustavsson et al. (1998) |

|

Goldberg et al. (2001) |

|

|

Marchand et al. (2000) |

Marchand et al. (2000) |

Parent et al. (2000) |

Parent et al. (1998) |

|

|

|

Merletti et al. (1991) |

Muscat and Wynder (1992) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wortley et al. (1992) |

|

|

|

|

Medium |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 unique citations |

|

Brown et al. (1988) |

|

Cocco et al. (1994) |

Demers et al. (1994) |

|

|

|

Burch et al. (1981) |

|

Krstev et al. (2005) |

Fredriksson et al. (1989) |

|

|

|

De Stefani et al. (1998) |

|

|

Garabrant et al. (1992) |

|

|

|

Elci et al. (2002) |

|

|

Hardell (1981) |

|

|

|

Hinds et al. (1979) |

|

|

Neugut et al. (1991) |

|

|

Luce et al. (2000) |

Luce et al. (2000) |

|

|

Spiegelman and Wegman (1985) |

|

|

|

Zagraniski et al. (1986) |

|

|

|

|

Quality of Exposure Characterization |

Type of Cancer Investigated |

||||

|

Pharyngeal |

Laryngeal |

Esophageal |

Stomach |

Colorectal |

|

|

Low |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 unique citations |

|

Ahrens et al. (1991) |

|

Ekstrom et al. (1999) |

Gerhardsson de Verdier et al. (1992) |

|

|

|

Olsen and Sabroe (1984) |

Hillerdal (1980) |

Hillerdal (1980) |

Hillerdal (1980) |

|

|

|

Shettigara and Morgan (1975) |

|

|

Vineis et al. (1993) |

|

|

|

Stell and McGill (1973) |

|

|

|

|

|

Zheng et al. (1992b) |

Zheng et al. (1992a) |

|

|

|

|

36 unique citations |

6 |

18 |

3 |

5 |

11 |

differentiation among histologic types. For example (although not specifically considered in the studies gathered for this review), esophageal cancer can be squamous or it can be adenocarcinomatous; the types are biologically and epidemiologically distinct. Second, cases can be (and generally are) studied shortly after diagnosis, and so survival rates do not so strongly influence case inclusion, as they do in occupational cohorts that rely on mortality records to define outcomes. Incidence-based case-control studies would be expected to be useful for investigating all the cancers in this review aside from esophageal cancer. Third, case-control studies are well suited to less common diseases, which would not occur in enough subjects in a typically sized cohort to permit any detailed analysis. This characteristic applies to laryngeal, pharyngeal, esophageal, and stomach cancers. Finally, case-control studies are well suited to exposures that cause disease only after a long latent period, as is presumed to occur between asbestos exposure and cancer.

Case-control studies also have disadvantages. First, there is a potential of unanticipated selection factors in choosing controls, leading to selection bias. Second, because the design is retrospective, it can be unclear whether exposure preceded or concurred with the outcome of cancer, although this

is unlikely to be an issue for health effects arising from asbestos exposure, which typically have long latency periods. Third, recall bias poses some concern, but the greatest disadvantage and challenge of case-control studies is the overall difficulty of validly and reliably assessing exposure.

Health Outcome Data

Case-control studies examine the association between asbestos and cancer by identifying people with cancer (cases) and comparing their asbestos exposure with that of people without cancer (controls). Because exposures occurred in the past, the case-control design is termed retrospective. Cases can be ascertained over a specified period from a hospital or medical practice where cancer is treated. When cases are selected that way, the case-control study is called a hospital-based case-control study and typically involves as controls people who were treated at the same institutions for noncancer conditions. Cases can also be ascertained from a source that allows identification of all cancer occurring within a defined geographic area over some period, often through a hospital network or cancer registry. This type of case-control study is called a population-based case-control study and typically involves as controls people sampled in the underlying community from which cases arose. For example, controls may be selected from driver’s-license or voter-registration lists, by random dialing of telephone numbers, or by random contacting of neighbors.

In either the hospital-based or the population-based design, the strategy is to find controls that differ from cases only with regard to asbestos exposure. Cases and controls should not systematically differ in other important respects. For that reason, the population-based case-control method is sometimes considered methodologically superior to the hospital-based method. In the latter, controls with diseases other than cancer may have nonrandom patterns of asbestos exposure. Every attempt is made to avoid selection of controls who would have been systematically exposed to asbestos, such as hospital-based people with pleural plaques or mesotheliomas. Similarly, every attempt is made to avoid controls who systematically would not have been exposed to asbestos. For example, one would avoid a comparison of men with cancer to women without cancer, because women are less likely to have worked in an asbestos-exposed occupation.

Exposure Assessment

Unlike cohort studies, which have access to workplace data, assessment of exposure in occupational case-control studies almost always relies on subject recall. Information on the type of asbestos fiber to which subjects were exposed was uniformly unavailable in the case-control studies. The

quality of an exposure assessment is determined by the type and amount of data collected, how the information was collected, and how it is used to assign exposure.

The best case-control studies collected detail lifetime work histories by using a structured interview or extensive questionnaires and assigned exposure on the basis of a review of the data by an “expert” in exposure or the use of a job-exposure matrix (JEM) created specifically to look at asbestos exposure. Those methods avoid some of the limitations of recall bias because exposure is not directly self-assessed, and they greatly improve the quality of the assessment.

Moderate-quality studies collected less detailed or more limited work-history information (for example, relied on proxy respondents or collected information on only the longest held jobs) or assigned exposure by using a multipurpose JEM that did not consider level of exposure. The best- and moderate-quality studies were combined in the exposure-assessment method (EAM) category “EAM = 1” for the meta-analyses.

The lowest-quality studies (“EAM = 2” for the meta-analyses) considered in this review used self-ascribed exposure based on direct questions or had very limited work-history information, as was the case for the lowest tier of studies in Table 6.5.

The method used to measure exposure to asbestos was an important criterion in reviewing the case-control studies. Case-control studies that used job information abstracted from death certificates were excluded from this evaluation, and none of those retained happened to have gathered exposure information from workplace records. They all used some sort of structured or semi-structured interview administered in person, over the telephone, or by mail (with or without the option of follow-up by telephone); these are listed in decreasing order of desirability. The committee decided to set aside case-control studies in which exposure to asbestos could only be inferred from an occupational category (such as insulator or ship repair) rather than from the original researchers’ explicit attribution of asbestos exposure.

The ability to assess dose-response relationships depends heavily on the quality of the underlying data. For example, dose-response relationships cannot be analyzed if the data collected were too crude to assign a level of exposure or some surrogate of dose. Therefore, the quality of exposure assessment correlates with the thoroughness and overall quality of analyses ultimately possible.

INTEGRATION OF EPIDEMIOLOGIC EVIDENCE WITH NON-EPIDEMIOLOGIC EVIDENCE

Results from epidemiologic studies of both cohort and case-control designs constitute an important component, but not the only type of evidence

considered in the approach applied in Chapters 7-11 to assess the likelihood and strength of causal associations between asbestos and cancer at the selected sites. The committee’s strategy for integrating all the evidence closely follows that used by the surgeon general’s report on health risks related to tobacco-smoking (HHS 2004). To illustrate, we would characterize as strongly supportive epidemiologic evidence those datasets that contain consistently increased risks with increasing dose-response gradients from both case-control studies performed in different places and cohort studies conducted in various industries. The magnitude of observed risks and their statistical precision also entered into the committee’s evaluations. Many of the case-control studies addressed potential confounding by non-occupational risk factors (such as smoking, alcohol use, and diet), but this was not possible in most cohort studies; these factors are seldom correlated with exposure strongly enough to greatly bias estimated risks through confounding (Axelson 1989, Kriebel et al. 2004). Consequently, the impossibility of controlling for potential confounding by risk factors not related to occupation was not considered a major concern for evaluation of the cohort studies. The epidemiologic evidence thus distilled is then considered in the context of the available non-epidemiologic information in reaching a determination about a causal role for asbestos exposure on a site-specific basis.

REFERENCES

(including references cited in Appendices B–F)

Acheson ED, Gardner MJ, Pippard EC, Grime LP. 1982. Mortality of two groups of women who manufactured gas masks from chrysotile and crocidolite asbestos: A 40-year follow-up. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 39(4): 344-348.

Acheson ED, Gardner MJ, Winter PD, Bennett C. 1984. Cancer in a factory using amosite asbestos. International Journal of Epidemiology 13(1): 3-10.

Ahrens W, Jockel K, Patzak W, Elsner G. 1991. Alcohol, smoking, and occupational factors in cancer of the larynx: A case-control study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 20(4): 477-493.

Albin M, Attewell R, Jakobsson K, Johansson L, Welinder H. 1988. [Total and cause-specific mortality in cohorts of asbestos-cement workers and referents between 1907 and 1985]. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 39 (4): 461-467.

Albin M, Jakobsson K, Attewell R, Johansson L, Welinder H. 1990. Mortality and cancer morbidity in cohorts of asbestos cement workers and referents. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 47(9): 602-610.

Albin M, Engholm G, Hallin N, Hagmar L. 1998. Impact of exposure to insulation wool on lung function and cough in Swedish construction workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(10): 661-667.

Alies-Patin AM, Valleron AJ. 1985. Mortality of workers in a French asbestos cement factory 1940-82. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 42(4): 219-225.

Aliyu OA, Cullen MR, Barnett MJ, Balmes JR, Cartmel B, Redlich CA, Brodkin CA, Barnhart S, Rosenstock L, Israel L, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Omenn GS. 2005. Evidence for excess colorectal cancer incidence among asbestos-exposed men in the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial. American Journal of Epidemiology 162(9): 868-878.

Amandus HE. 1986. Mortality from stomach cancer in United States cement plant and quarry workers, 1950-80. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(8): 526-528.

Amandus HE, Wheeler R. 1987. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: Part II. Mortality. American Journal Industrial Medicine 11(1): 15-26.

Amandus HE, Wheeler R, Jankovic J, Tucker J. 1987. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: Part I. Exposure estimates. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 11(1): 1-14.

Amandus HE, Wheeler R, Armstong BG, McDonald AD, Sebastien P. 1988. Mortality of vermiculite miners exposed to tremolite. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 32: 459-467.

Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH, Musk AW, Hobbs MS. 1988. Mortality in miners and millers of crocidolite in Western Australia. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 45(1): 5-13.

Axelson O. 1989. Confounding from smoking in occupational epidemiology. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 46(8): 505-507.

Axelsson G, Rylander R, Schmidt A. 1980. Mortality and incidence of tumours among ferrochromium workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 37(2): 121-127.

Band PR, Le ND, Fang R, Astrakianakis G, Bert J, Keefe A, Krewski D. 2001. Cohort cancer incidence among pulp and paper mill workers in British Columbia. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 27(2): 113-119.

Battista G, Belli S, Comba P, Fiumalbi C, Grignoli M, Loi F, Orsi D, Paredes I. 1999. Mortality due to asbestos-related causes among railway carriage construction and repair workers. Occupation Medicine (London) 49(8): 536-539.

Becker N. 1999. Cancer mortality among arc welders exposed to fumes containing chromium and nickel: Results of a third follow-up: 1989-1995. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 41(4): 294-303.

Berrino F, Richiardi L, Boffetta P, Esteve J, Belletti I, Raymond L, Troschel L, Pisani P, Zubiri L, Ascunce N, Guberan E, Tuyns A, Terracini B, Merletti F. 2003. Occupation and larynx and hypopharynx cancer: A job-exposure matrix approach in an international case-control study in France, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. Cancer Causes and Control 14(3): 213-223.

Berry G. 1981. Mortality of workers certified by pneumoconiosis medical panels as having asbestosis. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 38(2): 130-137.

Berry G. 1994. Mortality and cancer incidence of workers exposed to chrysotile asbestos in the friction-products industry. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 38(4): 539-546.

Berry G, Newhouse ML. 1983. Mortality of workers manufacturing friction materials using asbestos. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 40(1): 1-7.

Berry G, Gilson JC, Holmes S, Lewinsohn HC, Roach SA. 1979. Asbestosis: A study of dose-response relationships in an asbestos textile factory. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 36(2): 98-112.

Berry G, Newhouse ML, Antonis P. 1985. Combined effect of asbestos and smoking on mortality from lung cancer and mesothelioma in factory workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 42(1): 12-18.

Berry G, Newhouse ML, Wagner JC. 2000. Mortality from all cancers of asbestos factory workers in east London 1933-80. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57(11): 782-785.

Berry G, de Klerk NH, Reid A, Ambrosini GL, Fritschi L, Olsen NJ, Merler E, Musk AW. 2004. Malignant pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas in former miners and millers of crocidolite at Wittenoom, Western Australia. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 61(4): e14.

Blasetti F, Bruno C, Comba P, Fantini F, Grignoli M. 1990. [Mortality study of workers employed in the construction of railway cars in Collefero]. Medicina del Lavoro 81(5): 407-413.

Boffetta P, Burstyn I, Partanen T, Kromhout H, Svane O, Langard S, Jarvholm B, Frentzel-Beyme R, Kauppinen T, Stucker I, Shaham J , Heederik D, Ahrens W, Bergdahl IA, Cenee S, Ferro G, Heikkila P, Hooiveld M, Johansen C, Randem BG, Schill W. 2003. Cancer mortality among European asphalt workers: An international epidemiological study. II. Exposure to bitumen fume and other agents. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(1): 28-39.

Botta M, Magnani C, Terracini B, Bertolone GP, Castagneto B, Cocito V, DeGiovanni D, Paglieri P. 1991. Mortality from respiratory and digestive cancers among asbestos cement workers in Italy. Cancer Detection and Prevention 15(6): 445-447.

Braun DC, Truan TD. 1958. An epidemiological study of lung cancer in asbestos miners. AMA Archives of Industrial Health 17 (6): 634-653.

Britton M. 2002. The epidemiology of mesothelioma. Seminars in Oncology 29(1): 18-25.

Brown LM, Mason TJ, Pickle LW, Stewart PA, Buffler PA, Burau K, Ziegler RG, Fraumeni JF Jr. 1988. Occupational risk factors for laryngeal cancer on the Texas Gulf Coast. Cancer Research 48(7): 1960-1964.

Brown DP, Dement JM, Okun A. 1994. Mortality patterns among female and male chrysotile asbestos textile workers. Journal of Occupational Medicine 36(8): 882-888.

Burch JD, Howe GR, Miller AB, Semenciw R. 1981. Tobacco, alcohol, asbestos, and nickel in the etiology of cancer of the larynx: A case-control study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 67(6): 1219-1224.

Cantor KP, Sontag JM, Heid MF. 1986. Patterns of mortality among plumbers and pipefitters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 10(1): 73-89.

Carel R, Boffetta P, Kauppinen T, Teschke K, Andersen A, Jappinen P, Pearce N, Rix BA, Bergeret A, Coggon D, Persson B, Szadkowska-Stanczyk I, Kielkowski D, Henneberger P, Kishi R, Facchini LA, Sala M, Colin D, Kogevinas M. 2002. Exposure to asbestos and lung and pleural cancer mortality among pulp and paper industry workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44(6): 579-584.

Cheng WN, Kong J. 1992. A retrospective cohort study of chrysotile asbestos products workers in Tianjin 1972-1987. Environmental Research 59(1): 271-278.

Clemmensen J, Hjalgrim-Jensen S. 1981. Cancer incidence among 5686 asbestos-cement workers followed from 1943 through 1976. Ecotoxicology Environment Safety 5(1): 15-23.

Cocco P, Palli D, Buiatti E, Cipriani F, DeCarli A, Manca P, Ward MH, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr. 1994. Occupational exposures as risk factors for gastric cancer in Italy. Cancer Causes and Control 5(3): 241-248.

Coggiola M, Bosio D, Pira E, Piolatto PG, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Michelazzi M, Bacaloni A. 2003. An update of a mortality study of talc miners and millers in Italy. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(1): 63-69.

Costa G, Merletti F, Segnan N. 1989. A mortality cohort study in a north Italian aircraft factory. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 46(10): 738-743.

Danielsen TE, Langard S, Andersen A, Knudsen O. 1993. Incidence of cancer among welders of mild steel and other shipyard workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 50(12): 1097-1103.

Danielsen TE, Langard S, Andersen A. 1996. Incidence of cancer among Norwegian boiler welders. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 53(4): 231-234.

de Klerk NH, Armstrong BK, Musk AW, Hobbs MS. 1989. Cancer mortality in relation to measures of occupational exposure to crocidolite at Wittenoom Gorge in Western Australia. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 46(8): 529-536.

De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Oreggia F, Ronco A, Kogevinas M, Mendilaharsu M. 1998. Occupation and the risk of laryngeal cancer in Uruguay. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 33(6): 537-542.

Dement JM, Harris RL Jr, Symons MJ, Shy C. 1982. Estimates of dose-response for respiratory cancer among chrysotile asbestos textile workers. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 26(1-4): 869-887.

Dement JM, Harris RL Jr, Symons MJ, Shy C. 1983a. Exposures and mortality among chrysotile asbestos workers. Part I: Exposure estimates. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 4(3): 399-419.

Dement JM, Harris RL Jr, Symons MJ, Shy C. 1983b. Exposures and mortality among chrysotile asbestos workers. Part II: Mortality. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 4(3): 421-433.

Dement JM, Brown DP, Okun A. 1994. Follow-up study of chrysotile asbestos textile workers: Cohort mortality and case-control analyses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 26(4): 431-447.

Demers RY, Burns PB, Swanson GM. 1994. Construction occupations, asbestos exposure, and cancer of the colon and rectum. Journal of Occupational Medicine 36(9): 1027-1031.

Dietz A, Ramroth H, Urban T, Ahrens W, Becher H. 2004. Exposure to cement dust, related occupational groups and laryngeal cancer risk: Results of a population based case-control study. International Journal of Cancer 108(6): 907-911.

Djerassi L, Kaufmann G, Bar-Nets M. 1979. Malignant disease and environmental control in an asbestos cement plant. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 330: 243-253.

Doll R. 1955. Mortality from lung cancer in asbestos workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 12(2): 81-86.

Dumas S, Parent ME, Siemiatycki J, Brisson J. 2000. Rectal cancer and occupational risk factors: A hypothesis-generating, exposure-based case-control study. International Journal of Cancer 87(6): 874-879.

Ekstrom AM, Eriksson M, Hansson LE, Lindgren A, Signorello LB, Nyren O, Hardell L. 1999. Occupational exposures and risk of gastric cancer in a population-based case-control study. Cancer Research 59(23): 5932-5937.

Elci OC, Akpinar-Elci M, Blair A, Dosemeci M. 2002. Occupational dust exposure and the risk of laryngeal cancer in Turkey. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 28(4): 278-284.

Elmes PC, Simpson MJ. 1977. Insulation workers in Belfast: A further study of mortality due to asbestos exposure (1940-75). British Journal of Industrial Medicine 34(3): 174-180.

Enterline PE, Henderson V. 1973. Type of asbestos and respiratory cancer in the asbestos industry. Archives of Environmental Health 27(5): 312-317.

Enterline PE, Kendrick MA. 1967. Asbestos-dust exposures at various levels and mortality. Archives of Environmental Health 15(2): 181-186.

Enterline P, de Coufle P, Henderson V. 1972. Mortality in relation to occupational exposure in the asbestos industry. Journal of Occupational Medicine 14(12): 897-903.

Enterline P, de Coufle P, Henderson V. 1973. Respiratory cancer in relation to occupational exposures among retired asbestos workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 30(2): 162-166.

Enterline PE, Hartley J, Henderson V. 1987. Asbestos and cancer: A cohort followed up to death. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(6): 396-401.

Fear NT, Roman E, Carpenter LM, Newton R, Bull D. 1996. Cancer in electrical workers: An analysis of cancer registrations in England, 1981-1987. British Journal of Cancer 73(7): 935-939.

Finkelstein MM. 1984. Mortality among employees of an Ontario asbestos-cement factory. American Review of Respiratory Disease 129(5): 754-761.

Finkelstein MM. 1989a. Mortality rates among employees potentially exposed to chrysotile asbestos at two automotive parts factories. Canadian Medical Association Journal 141(2): 125-130.

Finkelstein MM. 1989b. Mortality among employees of an Ontario factory that manufactured construction materials using chrysotile asbestos and coal tar pitch. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 16(3): 281-287.

Finkelstein MM, Verma DK. 2004. A cohort study of mortality among Ontario pipe trades workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 61(9): 736-742.

Firth HM, Elwood JM, Cox B, Herbison GP. 1999. Historical cohort study of a New Zealand foundry and heavy engineering plant. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56(2): 134-138.

Fletcher AC, Engholm G, Englund A. 1993. The risk of lung cancer from asbestos among Swedish construction workers: Self-reported exposure and a job exposure matrix compared. International Journal of Epidemiology 22 (Supplement 2): S29-35.

Fredriksson M, Bengtsson NO, Hardell L, Axelson O. 1989. Colon cancer, physical activity, and occupational exposures: A case-control study. Cancer 63(9): 1838-1842.

Garabrant DH, Peters RK, Homa DM. 1992. Asbestos and colon cancer: Lack of association in a large case-control study. American Journal of Epidemiology 135(8): 843-853.

Gardner MJ, Winter PD, Pannett B, Powell CA. 1986. Follow up study of workers manufacturing chrysotile asbestos cement products. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(11): 726-732.

Gardner MJ, Powell CA, Gardner AW, Winter PD, Fletcher AC. 1988. Continuing high lung cancer mortality among ex-amosite asbestos factory workers and a pilot study of individual anti-smoking advice. Journal of the Society of Occupational Medicine 38(3): 69-72.

Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Plato N, Steineck G, Peters JM. 1992. Occupational exposures and cancer of the colon and rectum. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 22(3): 291-303.

Germani D, Belli S, Bruno C, Grignoli M, Nesti M, Pirastu R, Comba P. 1999. Cohort mortality study of women compensated for asbestosis in Italy. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 36(1): 129-134.

Giaroli C, Belli S, Bruno C, Candela S, Grignoli M, Minisci S, Poletti R, Ricco G, Vecchi G, Venturi G, Ziccardi A, Combra P. 1994. Mortality study of asbestos cement workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 66(1): 7-11.

Gibbs AR, Gardner MJ, Pooley FD, Griffiths DM, Blight B, Wagner JC. 1994. Fiber levels and disease in workers from a factory predominantly using amosite. Environmental Health Perspectives 102 (Supplement 5): 261-263.

Gillam JD, Dement JM, Lemen RA, Wagoner JK, Archer VE, Blejer HP. 1976. Mortality patterns among hard rock gold miners exposed to an asbestiform mineral. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 271: 336-344.

Goldberg MS, Parent ME, Siemiatycki J, Desy M, Nadon L, Richardson L, Lakhani R, Latreille B, Valois MF. 2001. A case-control study of the relationship between the risk of colon cancer in men and exposures to occupational agents. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 39(6): 531-546.

Goldstein B, Webster I, Harrison WO, Talent J. 1975. Epidemiological studies on asbestos-exposed workers in South Africa. Hefte Unfallheilkd (126): 538-542.

Gurvich EB, Gladkova EV, Gutnikova OV, Kostiukovskaia AV, Kuzina LE, Saprykova VV. 1993. [Epidemiology of chronic, precancerous and oncologic diseases in workers of asbestos and cement industry]. Meditsina Truda i Promyshlennaia Ekologiia 5-6: 4-6.

Gustavsson P, Jakobsson R, Johansson H, Lewin F, Norell S, Rutkvist LE. 1998. Occupational exposures and squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and oesophagus: A case-control study in Sweden. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(6): 393-400.

Hardell L. 1981. Relation of soft-tissue sarcoma, malignant lymphoma and colon cancer to phenoxy acids, chlorophenols and other agents. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 7(2): 119-130.

Henderson VL, Enterline PE. 1979. Asbestos exposure: Factors associated with excess cancer and respiratory disease mortality. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 330: 117-126.

HHS (US Department of Health and Human Services). 2004. The Health Effects of Active Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Hill ID, Doll R, Knox JF. 1966. Mortality among asbestos workers. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 59(1): 59-60.

Hillerdal G. 1980. Gastrointestinal carcinoma and occurrence of pleural plaques on pulmonary X-ray. Journal of Occupational Medicine 22(12): 806-809.

Hilt B. 1987. Non-malignant asbestos diseases in workers in an electrochemical plant. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(9): 621-626.

Hilt B, Andersen A, Rosenberg J, Langard S. 1991. Cancer incidence among asbestos-exposed chemical industry workers: An extended observation period. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 20(2): 261-264.

Hinds MW, Thomas DB, O’Reilly HP. 1979. Asbestos, dental X-rays, tobacco, and alcohol in the epidemiology of laryngeal cancer. Cancer 44(3): 1114-1120.

Hobbs MS, Woodward SD, Murphy B, Musk AW, Elder JE. 1980. The incidence of pneumoconiosis, mesothelioma and other respiratory cancer in men engaged in mining and milling crocidolite in Western Australia. IARC Scientific Publications 30: 615-625.

Hodgson J, Jones R. 1986. Mortality of asbestos workers in England and Wales 1971-1981. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(3): 158-164.

Hughes JM, Weill H. 1991. Asbestosis as a precursor of asbestos related lung cancer: Results of a prospective mortality study. British Journal Industrial Medicine 48(4): 229-233.

Hughes JM, Weill H, Hammad YY. 1987. Mortality of workers employed in two asbestos cement manufacturing plants. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(3): 161-174.

IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety). 1998. Chrysotile Asbestos: Environmental Health Criteria 203. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Jakobsson K, Albin M, Hagmar L. 1994. Asbestos, cement, and cancer in the right part of the colon. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 51(2): 95-101.

Jansson C, Johansson AL, Bergdahl IA, Dickman PW, Plato N, Admai J, Boffetta P, Lagergren J. 2005. Occupational exposures and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia cancers among male Swedish construction workers. Cancer Causes and Control 16(6): 755-764.

Jarvholm B, Sanden A. 1988. Asbestos-associated diseases in Swedish shipyard workers. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 39(4): 437-440.

Jarvholm B, Sanden A. 1998. Lung cancer and mesothelioma in the pleura and peritoneum among Swedish insulation workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(11): 766-770.

Johansen C, Olsen JH. 1998. Risk of cancer among Danish utility workers: A nationwide cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology 147(6): 548-555.

Jones JS, Smith PG, Pooley FD, Berry G, Sawle GW, Madeley RJ, Wignall BK, Aggarwal A. 1980. The consequences of exposure to asbestos dust in a wartime gas-mask factory. IARC Scientific Publications 30: 637-653.

Joubert L, Seidman H, Selikoff IJ. 1991. Mortality experience of family contacts of asbestos factory workers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 643: 416-418.

Karjalainen A, Pukkala E, Kauppinen T, Partanen T. 1999. Incidence of cancer among Finnish patients with asbestos-related pulmonary or pleural fibrosis. Cancer Causes and Control 10(1): 51-57.

Keal EE. 1960. Asbestosis and abdominal neoplasms. Lancet 2: 1214-1216.

Kjuus H, Andersen A, Langard S, Knudsen KE. 1986a. Cancer incidence among workers in the Norwegian ferroalloy industry. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(4): 227-236.

Kjuus H, Andersen A, Langard S. 1986b. Incidence of cancer among workers producing calcium carbide. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(4): 237-242.

Kleinfeld M, Messite J, Kooyman O. 1967. Mortality experience in a group of asbestos workers. Archives Environmental Health 15(2): 177-180.

Kleinfeld M, Messite J, Zaki MH. 1974. Mortality experiences among talc workers: A follow-up study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 16(5): 345-349.

Knox JF, Doll RS, Hill ID. 1965. Cohort analysis of changes in incidence of bronchial carcinoma in a textile asbestos factory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 132(1): 526-535.

Knox JF, Holmes S, Doll R, Hill ID. 1968. Mortality from lung cancer and other causes among workers in an asbestos textile factory. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 25(4): 293-303.

Kogan FM, Gusel’nikova NA, Gulevskaia MR. 1972. [Cancer mortality among workers in the asbestos industry of the Urals]. Gigiena I Sanitariia (Moskva) 37(7): 29-32.

Kogan PM, Yatsenko AS, Tregubov ES, Gurvich EB, Kuzina LE. 1993. Evaluation of carcinogenic risk in friction product workers. Medicina del Lavoro 84(4): 290-296.

Kolonel LN, Yoshizawa CN, Hirohata T, Myers BC. 1985. Cancer occurrence in shipyard workers exposed to asbestos in Hawaii. Cancer Research 45(8): 3924-3928.

Kriebel D, Zeka A, Eisen EA, Wegman DH. 2004. Quantitative evaluation of the effects of uncontrolled confounding by alcohol and tobacco in occupational cancer studies. International Journal of Epidemiology 33(5): 1040-1045.

Krstev S, Dosemeci M, Lissowska J, Chow WH, Zatonski W, Ward MH. 2005. Occupation and risk of stomach cancer in Poland. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62(5): 318-324.

Lacquet LM, van der Linden L, Lepoutre J. 1980. Roentgenographic lung changes, asbestosis and mortality in a Belgian asbestos-cement factory. IARC Scientific Publications 30: 783-793.

Langseth H, Andersen A. 2000. Cancer incidence among male pulp and paper workers in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 26(2): 99-105.

Latsenko AS, Kogan FM. 1990. [Occupational morbidity and mortality in malignant neoplasms among persons professionally exposed to asbestos dust]. Gigiena Truda I Professionalnye Zabolevaniia (Moskva) (2): 10-12.

Levin J, McLarty J, Hurst GA, Smith A, Frank AL. 1998. Tyler asbestos workers: Mortality experience in a cohort exposed to amosite. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(3): 155-160.

Liddell FD, Thomas DC, Gibbs GW, McDonald JC. 1984. Fibre exposure and mortality from pneumoconiosis, respiratory and abdominal malignancies in chrysotile production in Quebec, 1926-75. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 13 (2 Supplement): 340-344.

Liddell FD, McDonald AD, McDonald JC. 1997. The 1891-1920 birth cohort of Quebec chrysotile miners and millers: Development from 1904 and mortality to 1992. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 41(1): 13-36.

Luce D, Bugel I, Goldberg P, Goldberg M, Salomon C, Billon-Galland MA, Nicolau J, Quenel P, Fevotte J, Brochard P. 2000. Environmental exposure to tremolite and respiratory cancer in New Caledonia: A case-control study. American Journal of Epidemiology 151(3): 259-265.

Lumley KP. 1976. A proportional study of cancer registrations of dockyard workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 33(2): 108-114.

Magnani C, Nardini I, Governa M, Serio A. 1986. [A cohort study of the personnel assigned to a state railroad repair shop]. Medicina del Lavoro 77(2): 154-161.

Magnani C, Terracini B, Ivaldi C, Botta M, Budel P, Mancini A, Zanetti R. 1993. A cohort study on mortality among wives of workers in the asbestos cement industry in Casale Monferrato, Italy. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 50(9): 779-784.

Mancuso TF, Coulter EJ. 1963. Methodology in industrial health studies: The cohort approach with special reference to an asbestos company. Archives of Environmental Health 6: 36-52.

Mancuso TF, el-Attar AA. 1967. Mortality pattern in a cohort of asbestos workers: A study on employment experience. Journal of Occupational Medicine 9(4): 147-162.

Marchand JL, Luce D, Leclerc A, Goldberg P, Orlowski E, Bugel I, Brugere J. 2000. Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer and occupational exposure to asbestos and man-made vitreous fibers: Results of a case-control study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 37(6): 581-589.

McDonald AD, McDonald JC. 1978. Mesothelioma after crocidolite exposure during gas mask manufacture. Environmental Research 17(3): 340-346.

McDonald AD, Fry JS, Woolley AJ, McDonald JC. 1982. Dust exposure and mortality in an American factory using chrysotile, amosite, and crocidolite in mainly textile manufacture. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 39(4): 368-374.

McDonald AD, Fry JS, Woolley AJ, McDonald J. 1983. Dust exposure and mortality in an American chrysotile textile plant. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 40(4): 361-367.

McDonald AD, Fry JS, Woolley AJ, McDonald JC. 1984. Dust exposure and mortality in an American chrysotile asbestos friction products plant. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 41(2): 151-157.

McDonald JC, Liddell FD. 1979. Mortality in Canadian miners and millers exposed to chrysotile. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 330: 1-9.

McDonald JC, McDonald AD. 1997. Chrysotile, tremolite and carcinogenicity. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 41(6): 699-705.

McDonald JC, McDonald AD, Gibbs GW, Siemiatycki J, Rossiter CE. 1971. Mortality in the chrysotile asbestos mines and mills of Quebec. Archives of Environmental Health 22(6): 677-686.

McDonald JC, Liddell FD, Gibbs GW, Eyssen GE, McDonald AD. 1980. Dust exposure and mortality in chrysotile mining, 1910-75. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 37(1): 11-24.

McDonald JC, McDonald AD, Armstrong B, Sebastien P. 1986. Cohort study of mortality of vermiculite miners exposed to tremolite. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 43(7): 436-444.

McDonald JC, McDonald AD, Sebastien P, Moy K. 1988. Health of vermiculite miners exposed to trace amounts of fibrous tremolite. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 45(9): 630-634.

McDonald JC, Liddell FD, Dufresne A, McDonald AD. 1993. The 1891-1920 birth cohort of Quebec chrysotile miners and millers: Mortality 1976-88. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 50(12): 1073-1081.

Melkild A, Langard S, Andersen A, Tonnessen JN. 1989. Incidence of cancer among welders and other workers in a Norwegian shipyard. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 15(6): 387-394.

Menegozzo M, Belli S, Bruno C, Canfora V, Costigliola A, Di Cintio P, Di Liello L, Grignoli M, Palumbo F, Sapio P, et al. 1993. [Mortality due to causes correlatable to asbestos in a cohort of workers in railway car construction]. Medicina del Lavoro 84(3): 193-200.

Menegozzo M, Belli S, Borriero S, Bruno C, Carboni M, Grignoli M, Menegozzo S, Olivieri N, Comba P. 2002. [Mortality study of a cohort of insulation workers]. Epidemiology Prevention 26(2): 71-75.

Merletti F, Boffetta P, Ferro G, Pisani P, Terracini B. 1991. Occupation and cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx in Turin, Italy. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 17(4): 248-254.