7

Pharyngeal Cancer and Asbestos

NATURE OF THIS CANCER TYPE

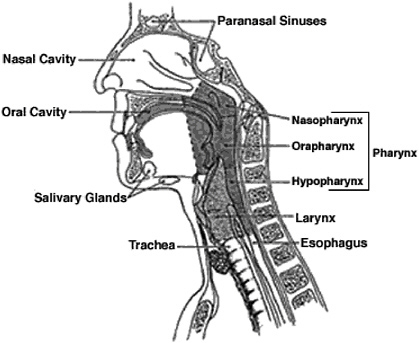

Cancers of the pharynx are frequently grouped with “head and neck cancers,” which also include the oral and nasal cavities. The pharynx itself spans several sublocations: the oropharynx (ICD-9 146; ICD-O-3 C09-C10), the nasopharynx (ICD-9 147; ICD-O-3 C11), and the hypopharynx (ICD-9 148; ICD-O-3 C12-C13.9). Each of those can be further subdivided (for example, the tonsil is located within the oropharynx), and the more specific locations have somewhat differing characteristics in terms of etiologic factors. During the time when most of the studies considered in this review were conducted, cancers of the oral (or buccal) cavity (ICD-9 141-145; ICD-O-3 C00-C09) were frequently grouped with the pharynx (particularly the oropharynx), and the committee decided to include such data. Similarly, the nasal cavities (ICD-9 160.0; ICD-O-3 C30) are sometimes grouped with the nasopharynx, but this did not arise in the informative studies screened for this review. Figure 7.1 illustrates the location of cancers that arise in the upper respiratory tract and digestive tract.

The American Cancer Society (Jemal et al. 2006) has projected that about 30,990 new cases of and 7,430 deaths from cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx will occur in 2006. Those estimates include cancers of the mouth (the inside lining of the lips and cheeks, gums, tongue, and hard and soft palate), nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx. In the study populations considered in this review, pharyngeal cancers would be expected to occur primarily in the oropharynx.

Cancer of the nasopharynx is rare in the United States, where it occurs

FIGURE 7.1 Anatomy of the pharynx showing its proximity to the oral and nasal cavities and to the larynx and esophagus.

SOURCE: Copyright 2005 American Cancer Society, Inc. Reprinted with permission from www.cancer.org.

at the rate of about one cancer per 100,000 per year, whereas the incidence is high in southern China (30-50 per 100,000 per year), among Eskimos in the Artic region, and among some indigenous populations in Southeast Asia. The risk is 2-3 times higher in men than in women. Risk factors include Epstein-Barr virus (Mueller 1995), consumption of salted fish (Miller et al. 1996), and occupational exposure to formaldehyde (IARC 1995). There are three histologic types: keratinizing squamous-cell carcinoma, non-keratinizing carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma.

Carcinoma of the hypopharynx is an uncommon disease. Considered collectively with carcinomas of the cervical esophagus, they make up about 10% of all tumors of the upper respiratory tract and digestive tract and less than 1% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States each year (Pfister et al. 2004). By far the most common histology is squamous-cell carcinoma. Cervical esophageal squamous-cell cancer and hypopharyngeal cancer typically present as extremely advanced disease, and 5-year survival is about 17-30%. Standard therapy for advanced disease is a combination of chemotherapy and radiation (Lefebvre et al. 1996). The major risk factors for

squamous-cell cancers of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus are tobacco and alcohol use. Ethanol is a promoter of the mutagenic effects of tobacco-derived substances and thereby contributes to the carcinogenic synergy seen with concurrent tobacco and alcohol use. The high incidence of second primary tumors and the concomitant mucosal dysplasia that frequently surrounds primary tumors suggest the presence of a regional field effect in these diseases.

For cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx overall, the incidence rate, or rate at which new cancers are diagnosed, is nearly 3 times higher in men than in women and slightly higher in black men than in white men. Most cases occur in men who are more than 50 years old. The incidence has decreased by an average of 1.2% per year since 1981; the decrease has been larger in men than in women and larger in black than in white men. Mortality from oropharyngeal cancer has been decreasing since the late 1970s, with more rapid improvement since 1993.

Most cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx are squamous-cell carcinomas. Development of cancers in the mouth may be preceded by the onset and progression of premalignant lesions, such as leukoplakia (raised white patches on the oral mucosa that measure at least 5 mm and cannot be scraped off) or erythroplasia (leukoplakia with an erythematous or red component).

Radiation therapy and surgery are standard treatments for cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx; in advanced disease, chemotherapy may be a useful addition. Survival varies with stage at diagnosis. For all stages combined, about 85% of persons with oral cavity or pharynx cancer survive 1 year after diagnosis. The 5-year and 10-year survival rates are 59% and 44%, respectively.

Known risk factors for cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx include all forms of tobacco-smoking (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and bidis), use of chewing tobacco or snuff, and excessive consumption of alcohol. The combination of tobacco use and alcohol consumption potentiates the risk of either factor alone. Premalignant lesions often regress after the discontinuation of smoking or using smokeless tobacco. Other factors that may contribute to risk are chronic irritation and infection with some strains of human papillomavirus.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC EVIDENCE CONSIDERED

Information on the association between asbestos exposure and cancer of the pharynx was available on 16 cohort populations with results presented in 14 articles and from six case-control studies. Cohort studies offer the opportunity to examine exposure-response trends, but the number of pharyngeal cancers in the cohort studies was generally too small to permit

examination by magnitude of exposure. Case-control studies are often based on larger numbers of cases, which tends to give them greater statistical power and the potential for stratification on tobacco or alcohol use. Both types of studies contributed evidence for the evaluation of asbestos and pharynx cancer.

Cohort Studies

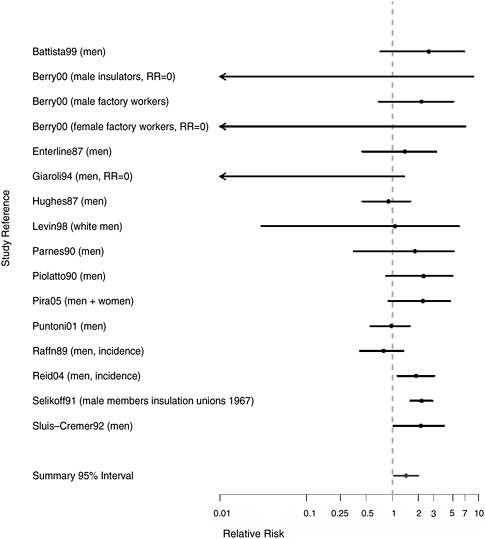

The cohorts that presented usable information about the risk of pharyngeal cancer were indicated in Table 6.1. Their histories and design properties are described in Table B.1, and the details of their results concerning cancer at this site are abstracted in Table D.1. The results of the cohort and case-control studies are summarized in Table 7.1, and Figures 7.2 and 7.3

TABLE 7.1 Summary of Epidemiologic Findings Regarding Cancer of the Pharynx

|

Study Type |

Figure |

Comparison |

Study Populations Included |

No. Study Populations |

Summary RR (95% CI) |

Between-Study SD |

|

Cohort |

Any vs none |

All |

16 |

1.44 (1.04-2.00) |

— |

|

|

|

High vs nonea |

|

3 |

0.93 (0.21-4.15) |

— |

|

|

Case- Control |

Any vs none |

All |

4 |

1.47 (1.10-1.96) |

0.00 |

|

|

|

Any vs none |

EAM = 1 |

3 |

1.37 (0.94-1.99) |

0.12 |

|

|

|

|

|

EAM = 2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Any vs none |

EAM = 1 Adjustedb |

2 |

1.39 (0.86-2.25) |

0.25 |

|

|

|

|

|

EAM = 1 Unadjustedb |

1 |

|

|

|

|

High vs nonea |

EAM = 1 |

4 |

1.25 (0.68-2.30) |

0.46 |

|

|

NOTE: CI = Confidence interval; EAM = exposure-assessment method; high quality, EAM = 1; lower quality, EAM = 2; RR = relative risk; SD = standard deviation. aUsed studies that reported dose-response relationship (RR on an exposure gradient). bAdjusted: RR was adjusted for both smoking and alcohol use. |

||||||

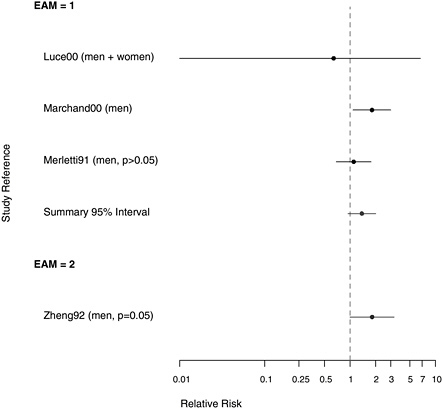

FIGURE 7.2 Cohort studies: RR of pharyngeal cancer in people with “any” exposure to asbestos compared with people who report none.

are plots of relative risks (RRs) for overall exposure and for exposure-response gradients from the cohort studies reviewed.

There were 16 cohort populations that had reported findings for this rare cause of death. The strongest evidence of an association comes from a study of insulation workers (Selikoff and Seidman 1991) with a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of 2.2 based on 48 cases of oropharyngeal cancer. The rest of the studies were based fewer than 10 cases. RRs were increased in a mining cohort (Piolatto et al. 1990), but there was no indication

FIGURE 7.3 Cohort studies: highest and lowest reported RRs of pharyngeal cancer among people in most extreme exposure category compared with those with none.

of an exposure-response trend. There was also an increased risk based on seven deaths due to oral or pharyngeal cancer in a cohort of Italian textile workers (Pira et al. 2005), but no increase in a larger cohort of Danish cement workers (Raffn et al. 1989). Although most of the studies reporting any RR for pharyngeal cancer were positive, results were based on small numbers.

The estimated aggregated RR of pharyngeal cancers for any exposure to asbestos was 1.44 (95% CI 1.04-2.00). Few studies evaluated exposure-response trends, and there was no indication of higher risk associated with more extreme exposures (RR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.21-4.15).

Case-Control Studies

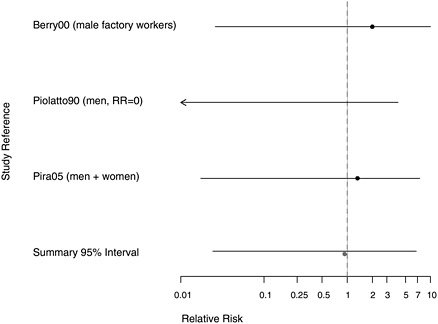

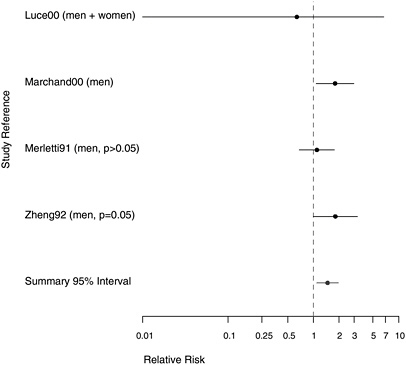

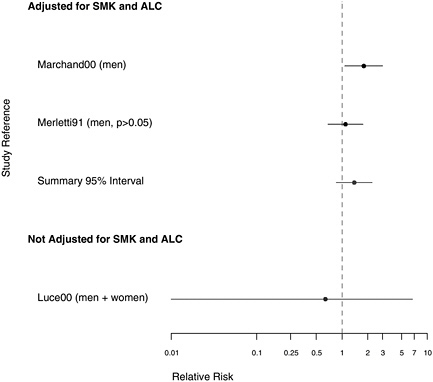

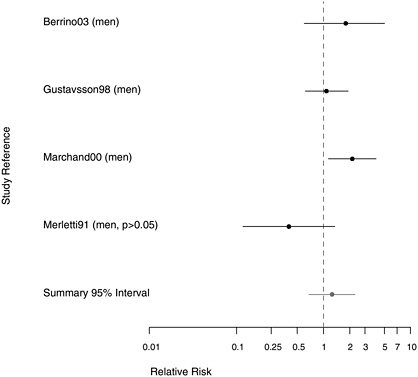

The six case-control studies retained for thorough evaluation after exclusion of studies that did not assess exposure to asbestos or did not meet other exclusion criteria are listed in Table 6.5 according to quality of their exposure assessment. The details of the design aspects of those studies are presented in Table C.1, and their detailed results are abstracted in Table E.1. The findings of those studies are summarized in Table 7.1 and in the plots presented in Figures 7.4-7.7.

FIGURE 7.4 Case-control studies: RR of pharyngeal cancer in people with “any” exposure to asbestos compared with people with none.

The committee found only six case-control studies that assessed the association between pharyngeal cancer and asbestos exposure. Of the four studies with contrasts of any versus no asbestos exposure, one had only a yes-no exposure classification; of the other three studies, two gathered data on potential confounders and adjusted the risk estimates associated with asbestos exposure accordingly. Two of these four studies also had results from dose-response gradients. Two additional studies (Berrino et al. 2003, Gustavsson et al. 1998) had information on gradients without combined results for all asbestos-exposed cases.

Four of the studies adjusted for alcohol use and smoking. Of those, the largest was by Marchand et al. (2000), whose hospital-based study of 206 total hypopharynx cases and 305 controls was designed to assess the effects of occupational exposures to asbestos and man-made mineral fibers. They reported an RR of 1.80 (95% CI 1.08-2.99) for those ever exposed to asbestos, adjusted for smoking and alcohol consumption. In an analysis by magnitude of exposure, the RR was increased in all categories, but there was little evidence of a trend with increasing exposure. Marchand et al. (2000) also estimated the joint effects of smoking and asbestos. When the

FIGURE 7.5 Case-control studies: RR of pharyngeal cancer in people with “any” exposure to asbestos compared with people with none, stratified on quality of exposure assessment (top, EAM = 1: higher-quality exposure assessment; bottom, EAM = 2: lower-quality exposure assessment).

data were looked at in a stratified fashion (Table 7.2), there was some suggestion that smoking modified the risk of hypopharyngeal cancer associated with asbestos exposure, which was comparable with their findings on the association of smoking and asbestos exposure with laryngeal cancer (Table 8.2).

In a European multicenter study of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, Berrino et al. (2003) found similar results when comparing the asbestos exposure of 100 men diagnosed with hypopharyngeal cancer before age 55 with 819 controls. The odds ratios (ORs) for those with either possible or probable exposure to asbestos were both 1.8, adjusted for alcohol consumption and smoking; there was no examination of effect modification. When these 100 cases of hypopharyngeal cancer were analyzed in combination with 215 cases of laryngeal cancer (see Table E.2), the OR increased slightly with duration of exposure. Merletti et al. (1991) found an RR of

FIGURE 7.6 Case-control studies: RR of pharyngeal cancer in people with “any” exposure to asbestos compared with people with none, in studies with higher-quality exposure assessment, stratified on quality of confounder assessment (top: adjusted; bottom: unadjusted).

1.1 in a population-based case-control study of 86 men with cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx, of whom 45 had definitely been exposed to asbestos. In a study of 138 Swedish men with pharyngeal cancer, Gustavsson et al. (1998) found no suggestion of an association of this cancer with asbestos exposure.

The other two case-control studies failed to adjust for confounding. Zheng et al. (1992) conducted a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China, using 204 incident cases of pharyngeal cancer and 414 controls, with the primary purpose of investigating the role of diet in pharyngeal-cancer causation; more asbestos exposure was seen in the cases than the controls, and the crude RR was 1.7. In a case-control study of only 5 cases of hypopharyngeal cancer among residents of New Caledonia, Luce et al. (2000) found no indication of increased risk of pharyngeal cancer with exposure to tremolite asbestos in whitewash.

FIGURE 7.7 Case-control studies: RR of pharyngeal cancer among people in the most extreme exposure category compared with those with none. (If multiple exposure gradients were presented in study, highest and lowest estimates for the most extreme categories were plotted.)

TABLE 7.2 Effect Modification for Pharyngeal Cancer Associated with Asbestos Exposure and Smoking

|

Study |

Smoking History (pack-years) |

RRs with 95% CIs for Asbestos Exposure |

|

|

None or Low (cumulative) |

Intermediate or High (cumulative) |

||

|

Marchand et al. (2000) (adjusted for age and for alcohol consumption) |

<30 30+ |

1.0 4.0 (2.2-7.2) |

1.2 (0.6-2.3) 6.2 (3.4-11.4) |

EVIDENCE INTEGRATION AND CONCLUSION

Evidence Considered

The committee reviewed 16 cohort populations and six case-control studies of pharyngeal cancer, of which four included high-quality exposure assessment or adjustment for possible confounding by smoking and alcohol consumption. The committee noted that epidemiologic evidence on pharyngeal cancer was based on a more heterogeneous grouping of subsites than was the evidence on cancer at the other selected sites considered in this review. No increase in pharyngeal tumors has been observed in animals exposed chronically to asbestos by inhalation (Hesterberg et al. 1993, 1994; McConnell 2005; McConnell et al. 1994a,b, 1999).

Consistency

Overall, the cohort studies were rather consistent; the plots present a pattern of modestly positive associations which is similar, to but fainter than, that seen for laryngeal cancer (see Chapter 8). Few RRs were less than 1.0. The few case-control studies were inconsistent and showed some suggestion of effect modification by smoking.

Although the information from the case-control studies was sparse, the aggregated risk estimate for any asbestos exposure was modest and similar to that for the more numerous cohort studies. For both types of study, the limited data on extreme exposures tended toward lower risks than the aggregate risk for any exposure, suggesting the lack of a dose-response relationship.

Strength of Association

The summary RR for the cohort studies was almost exactly midway between 1.0 and 2.0, but there were too few studies with quantitative measures of exposure to examine exposure-response trends.

Coherence

Squamous-cell carcinomas arising from the oropharynx and hypopharynx are similar to squamous-cell carcinomas of the lung and larynx in their histogenesis; however, they arise from oral and pharyngeal epithelium, which differs from the respiratory epithelium from which lung and laryngeal cancers arise. The major risk factors for pharyngeal cancer are tobacco-smoking, tobacco-chewing, and use of snuff alone or in combination with alcohol consumption. The combination of asbestos exposure and tobacco-smoking is an established risk factor for lung cancer, but for pha-

ryngeal cancer only a single case-control study has addressed asbestos exposure as a cofactor with tobacco use.

There are no published reports of recovery of asbestos fibers or asbestos bodies from the pharynx; the absence of such data neither supports nor refutes the possibility that fibers accumulate at this site.

Conclusion

Several cohort studies suggest an association between pharyngeal cancer and asbestos. The contrast with the abundance and consistency of data available on the larynx, the absence of information on a dose-response relationship, and the lack of supportive data from animal studies reduce the overall degree of evidence for causality. Nonetheless, several of the positive cohort studies and at least one case-control study support the determination that the evidence is suggestive but not sufficient to infer a causal relationship between asbestos exposure and pharyngeal cancer.

REFERENCES

Battista G, Belli S, Comba P, Fiumalbi C, Grignoli M, Loi F, Orsi D, Paredes I. 1999. Mortality due to asbestos-related causes among railway carriage construction and repair workers. Occupation Medicine (London) 49(8): 536-539.

Berrino F, Richiardi L, Boffetta P, Esteve J, Belletti I, Raymond L, Troschel L, Pisani P, Zubiri L, Ascunce N, Guberan E, Tuyns A, Terracini B, Merletti F. 2003. Occupation and larynx and hypopharynx cancer: A job-exposure matrix approach in an international case-control study in France, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. Cancer Causes and Control 14(3): 213-223.

Berry G, Newhouse ML, Wagner JC. 2000. Mortality from all cancers of asbestos factory workers in east London 1933-80. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57(11): 782-785.

Enterline PE, Hartley J, Henderson V. 1987. Asbestos and cancer: A cohort followed up to death. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(6): 396-401.

Giaroli C, Belli S, Bruno C, Candela S, Grignoli M, Minisci S, Poletti R, Ricco G, Vecchi G, Venturi G, Ziccardi A, Combra P. 1994. Mortality study of asbestos cement workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 66(1): 7-11.

Gustavsson P, Jakobsson R, Johansson H, Lewin F, Norell S, Rutkvist LE. 1998. Occupational exposures and squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and oesophagus: A case-control study in Sweden. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(6): 393-400.

Hesterberg TW, Miller WC, Mast R, McConnell EE, Bernstein DM, Anderson R. 1994. Relationship between lung biopersistence and biological effects of man-made vitreous fibers after chronic inhalation in rats. Environmental Health Perspectives 102 (Supplement 5): 133-137.

Hesterberg TW, Miller WC, McConnell EE, Chevalier J, Hadley JG, Bernstein DM, Thevenaz P, Anderson R. 1993. Chronic inhalation toxicity of size-separated glass fibers in Fischer 344 rats. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 20(4): 464-476.

Hughes JM, Weill H, Hammad YY. 1987. Mortality of workers employed in two asbestos cement manufacturing plants. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44(3): 161-174.

IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). 1995. Wood Dust and Formaldehyde. IARC Monograph on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 84. Lyon, France: World Health Organization. Pp. 282-294.

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun M. 2006. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 56: 106-130.

Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. 1996. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: Preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 88(13): 890-899.

Levin J, McLarty J, Hurst GA, Smith A, Frank AL. 1998. Tyler asbestos workers: Mortality experience in a cohort exposed to amosite. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(3): 155-160.

Luce D, Bugel I, Goldberg P, Goldberg M, Salomon C, Billon-Galland MA, Nicolau J, Quenel P, Fevotte J, Brochard P. 2000. Environmental exposure to tremolite and respiratory cancer in New Caledonia: A case-control study. American Journal of Epidemiology 151(3): 259-265.

Marchand JL, Luce D, Leclerc A, Goldberg P, Orlowski E, Bugel I, Brugere J. 2000. Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer and occupational exposure to asbestos and man-made vitreous fibers: Results of a case-control study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 37(6): 581-589.

McConnell EE. 2005 (October 27). Personal Communication to Mary Paxton for the Committee on Asbestos: Selected Health Effects. Available in IOM Public Access Files.

McConnell E, Kamstrup O, Musselman R, Hesterberg T, Chevalier J, Miller W, Thevenaz P. 1994a. Chronic inhalation study of size-separated rock and slag wool insulation fibers in Fischer 344/N rats. Inhalation Toxicology 6(6): 571-614.

McConnell E, Mast R, Hesterberg T, Chevalier J, Kotin P, Bernstein D, Thevenaz P, Glass L, Anderson R. 1994b. Chronic inhalation toxicity of a kaolin-based refactory cermaic fiber in Syrian golden hamsters. Inhalation Toxicology 6(6): 503-532.

McConnell EE, Axten C, Hesterberg TW, Chevalier J, Miller WC, Everitt J, Oberdorster G, Chase GR, Thevenaz P, Kotin P. 1999. Studies on the inhalation toxicology of two fiberglasses and amosite asbestos in the Syrian golden hamster: Part II. Results of chronic exposure. Inhalation Toxicology 11(9): 785-835.

Merletti F, Boffetta P, Ferro G, Pisani P, Terracini B. 1991. Occupation and cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx in Turin, Italy. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 17(4): 248-254.

Meurman LO, Pukkala E, Hakama M. 1994. Incidence of cancer among anthophyllite asbestos miners in Finland. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 51(6): 421-425.

Miller BA, Kolonel LN, Bernstein L, Young JL Jr, Swanson GM, West D, Key CR, Liff JM, Glover, Alexander GA (eds). 1996. Racial/Ethnic Patterns of Cancer in the United States 1988-1992. (NIH publication no. 96-4104). Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute.

Mueller N. 1995. Overview: Viral agents and cancer. Environmental Health Perspectives 103 (Supplement 8): 259-261.

Parnes SM. 1990. Asbestos and cancer of the larynx: Is there a relationship? Laryngoscope 100(3): 254-261.

Pfister DG, Hu KS, Lefebvre JL. 2004. Cancer of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus. In: Head and Neck Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Pp. 404-454.

Piolatto G, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Pira E, Decarli A, Peto J. 1990. An update of cancer mortality among chrysotile asbestos miners in Balangero, northern Italy. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 47(12): 810-814.

Pira E, Pelucchi C, Buffoni L, Palmas A, Turbiglio M, Negri E, Piolatto PG, La Vecchia C. 2005. Cancer mortality in a cohort of asbestos textile workers. British Journal of Cancer 92(3): 580-586.

Puntoni R, Merlo F, Borsa L, Reggiardo G, Garrone E, Ceppi M. 2001. A historical cohort mortality study among shipyard workers in Genoa, Italy. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 40(4): 363-370.

Raffn E, Lynge E, Juel K, Korsgaard B. 1989. Incidence of cancer and mortality among employees in the asbestos cement industry in Denmark. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 46(2): 90-96.

Reid A, Ambrosini G, de Klerk N, Fritschi L, Musk B. 2004. Aerodigestive and gastrointestinal tract cancers and exposure to crocidolite (blue asbestos): Incidence and mortality among former crocidolite workers. International Journal of Cancer 111(5): 757-761.

Selikoff IJ, Seidman H. 1991. Asbestos-associated deaths among insulation workers in the United States and Canada, 1967-1987. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 643: 1-14.

Sluis-Cremer GK, Liddell FD, Logan WP, Bezuidenhout BN. 1992. The mortality of amphibole miners in South Africa, 1946-80. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 49(8): 566-575.

Zheng W, Blot WJ, Shu XO, Diamond EL, Gao YT, Ji BT, Fraumeni JF Jr. 1992. Risk factors for oral and pharyngeal cancer in Shanghai, with emphasis on diet. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 1(6): 441-448.