4

Government

Government serves several vital functions in a national public health crisis such as the childhood obesity epidemic. First and foremost the government provides leadership, which it demonstrates by making the response to the obesity epidemic an urgent public health priority and coordinating the public- and private-sector response. Galvanizing the response involves political commitment, policy development, prioritized funding, and coordination of programs. Other necessary elements of an adequate government response to the obesity epidemic are a strong governmental workforce, an enhanced organizational capacity, and a robust information-gathering system to monitor progress and guide programs and policies (Baker et al., 2005). Another key governmental function at the federal, state, and local levels is to improve the health status of the population and reduce inequities in health status among population groups (Health Canada, 2001; IOM, 2003).

In responding to the obesity epidemic, federal, state, and local government agencies across the nation share in the core public health responsibilities listed in Box 4-1 (IOM, 1988, 2003; NACCHO, 2005). Research and technical assistance for implementing, evaluating, and achieving national and regional objectives are primarily the responsibilities of the federal government, whereas program planning, implementation, and evaluation are state and local government responsibilities in partnership with other sectors (TFAH, 2006).

Two major recommendations in the Health in the Balance report were that “government at all levels should provide coordinated leadership for the

|

BOX 4-1 Public Health Mission and Government Responsibilities Mission: The mission of public health is to fulfill society’s interest in ensuring the existence of conditions in which people can be healthy. Core Functions: All levels of government are responsible for conducting health assessments, health policy development, and the assurance of health. To accomplish its mission, public health agencies should establish operational linkages with other public sector agencies responsible for health-related functions. The execution of public health functions requires technical, political, management, program, and fiscal capacities at all levels. State government is the central force in public health and is the public-sector entity that bears primary responsibility for health. Federal Government Responsibilities

State Government Responsibilities

|

prevention of obesity in children and youth” and an “increased level and sustained commitment of federal and state funds and resources are needed” to sufficiently address the childhood obesity epidemic. Additionally, the report recommended that state and local government should “provide coordinated leadership and support for childhood obesity efforts, particularly for populations at high risk of childhood obesity, by increasing resources and strengthening policies that promote opportunities for physical activity and healthful eating” (IOM, 2005a, p. 147–148).

Many of the efforts that have already been implemented by federal, state, and local governments play an essential role in the response to childhood obesity in the United States. The number of existing governmental

Local Government Responsibilities

SOURCES: Adapted from IOM (1988, 2003); NACCHO (2005). |

activities with the potential to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic is vast, dynamic, and difficult to track systematically over time. The prevention of childhood obesity will require contributions from all sectors of society. Government can play a special role by augmenting its own capacity in such a way that it stimulates and enhances the capacities and activities of other sectors of society. In order to continue to focus attention on the childhood obesity epidemic and encourage sustained efforts from all sectors of society, government will need to consistently acknowledge the importance of preventing childhood obesity.

In addition to implementing and sustaining new programs, governmental agencies at all levels need to reexamine their existing policies and initia-

tives that may hinder progress toward childhood obesity prevention. Examples include school siting policies that locate schools far outside of walking distance from the neighborhoods that those schools serve; U.S. agricultural policies including marketing practices, nutrition standards, agricultural subsidies, and procurement policies for agricultural commodity programs that affect the types and quantities of foods and beverages available in schools, communities, and through federal food assistance programs; land use policies that do not encourage mixed use of residential and business space and that subsequently discourage walking to neighborhood stores or businesses; and school policies that shorten the length of time in the school day devoted to healthy school meals and physical activity.

This chapter provides an overview of the role of government at all levels in the response to the childhood obesity epidemic. It provides examples of the policies, programs, and activities undertaken by federal, state, and local governmental agencies to reverse the current obesity epidemic and prevent a future rise in childhood obesity rates. The chapter examines the approaches needed to effectively evaluate policies and interventions and explores the factors that constitute success for the governmental sector. The chapter also recommends next steps in assessing progress with regard to leadership; implementing and evaluating policies and interventions and developing evaluation capacity; enhancing surveillance, monitoring, and research efforts; and using and disseminating the evidence from evaluation results.

SETTING THE CONTEXT

The severity of the obesity epidemic in the United States was first observed and publicized with data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). BRFSS is a system that uses telephone interviews for health surveillance and is jointly managed by the 50 state health departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. In 1991, BRFSS data showed that four states had adult obesity prevalence rates of 15 to 19 percent and that no states had rates of 20 percent or greater. By 2004, BRFSS showed that 7 states had adult obesity prevalence rates of 15 to19 percent, 33 states had adult obesity rates of 20 to 24 percent, and 9 states had adult obesity rates of 25 percent or greater (CDC, 2005a).

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a CDC surveillance system that is based on personal interviews and a physical examination and that was initiated in 1971, also revealed a rapidly evolving obesity epidemic in children, adolescents, and adults (Flegal et al., 2002; Ogden et al., 2002, 2006; Troiano et al., 1995). CDC presented the emerging data to the U.S. Congress at a House Appropriations Hearing in

2000 and warned of a growing obesity epidemic in children and adults. These data, coupled with evidence that obesity is not merely a cosmetic issue but leads to an array of serious health problems and comorbidities (Williams et al., 2005) as well as increasing health care costs (DHHS, 2001; Finkelstein et al., 2003, 2004; Wang and Dietz, 2002), were sufficient to raise national concern about the urgency of the epidemic and to stimulate congressional action. In 2001, the U.S. Surgeon General issued the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity to stimulate the development of specific agendas and actions targeting this growing public health problem (DHHS, 2001).

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) undertook a congressionally mandated study to develop a blueprint for a comprehensive action plan that is summarized in the report, Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance (IOM, 2005a). The recommendations from that report focused on the actions needed by multiple stakeholders; the report called on government at all levels to take a leadership role and to bring resources to bear on this important health concern. The present IOM committee recommends increased efforts to address the government recommendations of the Health in the Balance report (Boxes 4-2 to 4-4) and to incorporate an evaluation component into all policies, programs, and initiatives.

To explore the breadth of childhood obesity prevention activities currently under way in the government sector—and whether and how they are being evaluated—the committee reviewed and drew information from a variety of sources, including those described in Chapter 1, as well as information and data from federal and state government surveillance and reporting systems, reports, and websites and from interviews conducted with selected state health officials; federal regulatory agencies; and federal representatives of the health, agriculture, and education sectors. A complete and systematic inventory of federal, state, and local government policies, programs, and activities relevant to childhood obesity prevention was beyond the charge of the committee and the scope of this progress report. However, a selected list of recent federal agency programs, initiatives, and surveillance systems relevant to childhood obesity prevention is compiled in Appendix D.

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

The federal government has a responsibility to address public health crises including the childhood obesity epidemic through ensuring sufficient capacity to provide essential public health services; responding when a health threat is apparent across the entire country, region, or many states; providing assistance when the responses are beyond the jurisdictions of individual states; helping to formulate the public health goals of state and

|

BOX 4-2 Recommendations for Federal, State, and Local Government from the 2005 IOM report Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance Government at all levels should provide coordinated leadership for the prevention of obesity in children and youth. The president should request that the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) convene a high-level task force that includes the Secretaries or senior officials from DHHS, Agriculture, Education, Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Defense, and other relevant agencies to ensure coordinated budgets, policies, and program requirements and to establish effective interdepartmental collaboration and priorities for action. An increased level and a sustained commitment of federal and state funds and resources are needed. To implement this recommendation, the federal government should:

To implement this recommendation, state and local governments should:

Community Programs Local governments, public health agencies, schools, and community organizations should collaboratively develop and promote programs that encourage healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity, particularly for populations at high risk of childhood obesity. Community coalitions should be formed to facilitate and promote crosscutting programs and communitywide efforts. SOURCE: IOM (2005a). |

|

BOX 4-3 Recommendations for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services from the 2005 IOM report Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance Advertising and Marketing Industry should develop and strictly adhere to marketing and advertising guidelines That minimize the risk of obesity in children and youth. To implement this recommendation:

Multimedia and Public Relations Campaign The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should develop, implement, and evaluate a long-term national multimedia and public relations campaign focused on obesity prevention in children and youth. To implement this recommendation:

Nutrition Labeling Nutrition labeling should be clear and useful so that parents and youth can make informed product comparisons and decisions to achieve and maintain energy balance at a healthy weight. To implement this recommendation:

Built Environment The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Transportation should:

SOURCE: IOM (2005a). |

|

BOX 4-4 Recommendations for Other Relevant Federal Agencies Recommendations from the 2005 IOM report Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance U.S. Department of Education Schools Schools should provide a consistent environment that is conducive to healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity. To implement this recommendation: Federal and state departments of education and health and professional organizations should

U.S. Department of Transportation Built Environment The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Transportation should

Federal Trade Commission Advertising and Marketing Industry should develop and strictly adhere to marketing and advertising guidelines that minimize the risk of obesity in children and youth. To implement this recommendation:

U.S. Department of Agriculture Schools Schools should provide a consistent environment that is conducive to healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity. To implement this recommendation: The U.S. Department of Agriculture, state and local authorities, and schools should

SOURCE: IOM (2005a). |

local governments; and assisting states when they lack resources or expertise to adequately respond to a public health crisis (TFAH, 2006).

The U.S. Congress and several federal executive branch departments have become actively engaged in obesity prevention. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) are demonstrating leadership in these efforts, with growing involvement of the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Transportation. However, a great deal more must be accomplished. Examples of the federal agency programs, initiatives, and surveillance systems that support and monitor the prevention of obesity in U.S. children and youth are discussed throughout this chapter, with additional information provided in Appendix D, including information on the extent and the nature of federal evaluation efforts based on the available data. It should be noted that this report is not a complete and systematic inventory of government programs and initiatives, as this was not the charge to the committee. Rather, the committee highlights some of the efforts that illustrate the key roles of government and that point to further work that can be done to increase the opportunities for children and youth to become more physically active and improve their eating patterns and diets.

Leadership

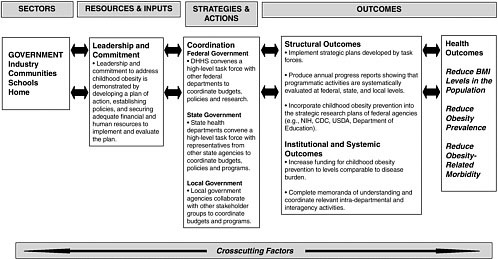

Leadership is an essential function of the federal government as it determines the priorities for funding and brings its considerable resources to bear on the problem. Government leadership influences the actions of those working within the federal government and across other sectors. Evidence of leadership includes the acknowledgement of and commitment to address a problem, followed by the development of a plan of action, the establishment of policies, and the commitment of financial and human resources to carry out a comprehensive and coordinated plan. The Health in the Balance report recommended federal leadership through the following actions (IOM, 2005a):

-

The president should appoint a high-level task force to coordinate federal agency responses.

-

DHHS and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should develop guidelines with broad stakeholder input for the advertising and marketing of foods, beverages, and sedentary entertainment directed at children and youth, with attention to product placement, promotion, and content.

-

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should revise the Nutrition Facts panel on packaged food and beverage products.

-

FDA should allow industry to have greater flexibility to use evidence-based nutrient and health claims regarding the link between

-

the nutritional properties or the biological effects of foods and a reduced risk of obesity and related chronic diseases.

-

USDA should develop nutritional standards for competitive foods and beverages available in schools.

An example of demonstrated federal leadership is an initial stakeholder workshop, jointly organized by FTC and DHHS, to develop guidelines for the advertising and marketing of foods, beverages, and sedentary entertainment to children and youth. In July 2005, FTC and DHHS held a joint workshop, Marketing, Self-Regulation, and Childhood Obesity, that provided a forum for industry, academic, public health advocacy, and government stakeholders, as well as consumers, to examine the role of the private sector in addressing the rising childhood obesity rates. A summary of the workshop (FTC and DHHS, 2006) contains recommendations and next steps for industry stakeholders, including a request that industry strengthen self-regulatory measures to advertise responsibly to children through the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU). FTC and DHHS indicated that both of these federal institutions plan to closely monitor the progress made on the recommendations in the joint FTC and DHHS summary report (FTC and DHHS, 2006). Moreover, Congress has requested that the FTC compile information on food and beverage marketing activities and expenditures targeted to children and adolescents. The FTC will be soliciting public comment on these issues, and the results will be submitted in a report to Congress as mandated in Public Law 109-108 (FTC, 2006) (Chapter 5).

Recent actions by FDA are providing steps toward improving consumer nutrition information. In April 2005, FDA released two advance notices of proposed rulemaking to elicit stakeholder and public input about two recommendations of the FDA Obesity Working Group: the first action was to make calorie information more prominent on the Nutrition Facts label and the second action provides more information about serving sizes on packaged foods (FDA, 2006). In September 2005, FDA issued a final rule on the nutrient content claims definition of sodium levels for the term healthy (FDA, 2006). The IOM committee awaits further progress that FDA can make toward finalizing the rulemaking and exploring the use of evidence-based nutrient and health claims regarding the link between the nutritional properties or biological effects of foods and a reduced risk of obesity and related chronic diseases.

Joint efforts by USDA and DHHS resulted in the release of the sixth edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, which provide specific recommendations on the consumption of foods in different food groups, fats, carbohydrates, sodium and potassium, and alcoholic beverages; food safety; and physical activity (DHHS and USDA, 2005). The Dietary Guidelines and their graphic representation, MyPyramid, are an

important source of consumer nutrition information that should provide the basis for federal food and nutrition assistance programs, nutrition education, and nutrition policies.

The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act (P.L. 108-265) provided another step forward for childhood obesity prevention efforts. In 2004, Congress initiated and passed the legislation, which requires school districts participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) or School Breakfast Program (SBP) to establish a local school wellness policy by the beginning of the 2006–2007 school year (CNWICRA, 2004). As outlined in the legislation, the school wellness policies should include goals for nutrition education, physical activity, guidelines for foods and beverages served throughout school campuses, and other school-based activities that are designed to promote student wellness in a manner that the local educational agency determines is appropriate. The USDA secretary, in coordination with the secretary of education and in consultation with the DHHS secretary, acting through CDC, are charged with providing technical assistance to establish healthy school nutrition environments, reducing childhood obesity, and preventing diet-related chronic diseases. The act establishes a plan for measuring the implementation of the local school wellness policy, supported by $4 million in appropriated funds (CNWICRA, 2004) (Chapter 7). The committee encourages the systematic monitoring and evaluation of the implementation and the impacts and outcomes of these policies throughout the nation’s school districts and local schools.

Progress is also under way to develop nutrition standards for competitive foods and beverages that are available in schools. In fiscal year (FY) 2005, Congress directed IOM to conduct a study to develop comprehensive recommendations for appropriate nutritional standards for competitive foods (Hartwig, 2004; IOM, 2006a). The study is in progress and when it is complete, the committee recommends that Congress, USDA, CDC, and other relevant agencies take expeditious action on developing national nutrition standards for competitive foods and beverages in schools.

The federal government has also demonstrated leadership in setting specific goals for childhood obesity prevention. DHHS incorporated into its Strategic Plan FY 2004–2009 an objective for the Indian Health Service to decrease obesity rates among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) children by 10 percent during this 5-year period (DHHS, 2004).

However, the committee noted that federal leadership fell short of an important recommendation in the Health in the Balance report, in that no progress was made toward the establishment of a presidentially appointed high-level task force to make childhood obesity prevention a national priority and to coordinate activities and budgets for this goal across federal agencies. Because childhood obesity prevention is a national priority that requires the collective efforts of many federal departments and agencies, the

establishment of a high-level task force to address this issue is essential for making progress.

Program Resources, Funding, and Evaluation

A public health program is a coordinated set of complementary activities designed to produce desirable health outcomes. Consistent with this consideration, substantial resources from a variety of federal government entities are designated for programs relevant to childhood obesity prevention. However, the level of funding and the resources invested in these efforts and their evaluation are not commensurate with the seriousness of this public health problem. Coordinated and sustained funding continues to be strengthened, however, as does the emphasis on program evaluation and the dissemination of evaluation results. For example, in 2005, the average per-capita federal investment in public health through CDC was $20.99. An estimated 80 percent of CDC funds are redistributed to states and private partners (TFAH, 2006). Throughout the country, the funding strategies that states and private partners use to support programs that promote healthy lifestyles and obesity prevention goals include making better use of existing resources, maximizing federal and state revenues, creating more flexibility in existing categorical funding, building public-private partnerships, and creating new dedicated revenue streams.

The amount of federal support that the states receive varies substantially. The following federal funding streams are especially relevant:

-

Formula and block grants, in which states receive a fixed allocation of funds based on a formula prescribed by law to address particular issues of national priority (e.g., preventive health and health services block grants, maternal and child health block grants, and Safe Routes to School grants);

-

Entitlements, which guarantee that individuals who meet the eligibility criteria for a specific program (e.g., low-income children and families participating in federal assistance programs such as the Food Stamps Program [FSP] and school meals) are served;

-

Discretionary or competitive project grants, which target particular federal efforts such as obesity prevention, fund states on the basis of the merits of their grant applications, and are awarded for a specific time frame (e.g., CDC’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases; USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC] and Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program [FFVP]);

-

Cooperative agreements, which have prescriptive project agreements (e.g., CDC’s Steps to a HealthierUS Initiative); and

-

Need-based formula grants, which are often based on the prevalence of a condition and that match the states’ costs on a formula basis (e.g., Medicaid, and USDA’s Food Stamp Nutrition Education [FSNE] program) (Finance Project, 2004; TFAH, 2006).

In assessing the overall progress in funding support for obesity prevention programs, however, it is important to ensure that double counting does not take place or that an increase in funding from one source (e.g., federal funding) is not accompanied by a reduction in funding from existing sources (e.g., state funding). Of the numerous federally funded programs relevant to childhood obesity prevention, only a few are highlighted below or in subsequent chapters and Appendix D.

The Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005a) recommended that the federal government undertake an independent assessment of federal nutrition assistance programs and agricultural policies to ensure that they promote healthful dietary intake and increase physical activity levels for all children and youth. To date, there have been limited analyses examining the relationships among U.S. food supply-related agricultural, industrial, and economic policies (or the environment resulting from these policies) and consumer demand-driven nutrition policies (e.g., dietary guidance) (Tillotson, 2004). Future efforts to improve the U.S. food and agricultural system will need to create connections among health, food, and farm policies that support the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. The 2007 U.S. Farm Bill, which contains a multitude of programs and provisions that will impact the U.S. food and agricultural system, is an opportunity to foster changes that support both healthier diets and strengthen agricultural economies (Schoonover and Muller, 2006).

USDA has many programs designed to directly influence dietary behaviors. In FY 2005, expenditures for USDA’s 15 federal food assistance programs totaled $50.7 billion. An estimated 55 percent of USDA’s budget supported programs that provide low-income families and children with access to food for a healthful diet and nutrition education (USDA, 2006b) (Table 4-1). USDA has indicated that it is committed to aligning its programs with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services, 2006). The contents of the WIC food packages are currently undergoing review, with a focus on implementing the recommendations of the IOM report, WIC Food Packages: Time for a Change (IOM, 2005b). The USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) is presently seeking public comments on proposed revisions to the regulations governing the contents of the WIC food packages to align them with the Dietary Guide-

TABLE 4-1 Expenditures for and Rates of Participation in Major Federal Food and Nutrition Assistance Programs, FY 2005

|

Federal Food and Nutrition Assistance Programs |

Average Monthly Participation or Nutrition Provided |

Annual Expenditures ($ billion) |

|

Food Stamp Program |

25.7 million participants |

31.0 |

|

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children |

8.0 million participants |

5.0 |

|

National School Lunch Program |

29.6 million participants |

8.0 |

|

School Breakfast Program |

9.3 million participants |

1.9 |

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program |

1,099.0 million meals served in child-care centers; 72.1 million meals served in family child-care centers; 57.3 million meals served in adult day-care centers |

2.1 |

|

SOURCE: USDA (2006b). |

||

lines for Americans 2005 and current infant feeding practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics (USDA, 2006d). The committee recommends that Congress and USDA expeditiously complete the revision of the contents of the WIC food packages and thoroughly examine other relevant food and nutrition assistance programs so that they can be strengthened to fully address childhood obesity prevention goals and to monitor and evaluate relevant outcomes.

In 1999, USDA funded a childhood obesity prevention initiative called Fit WIC to support and evaluate social and environmental approaches to prevent and reduce obesity in preschool-aged children. Four state WIC programs (California, Kentucky, Vermont, and Virginia) and the Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona received funds for a 3-year period to identify ways in which the WIC program could respond to the childhood obesity epidemic for program participants. The main finding from the five pilot projects was that many parents of obese preschool-aged children neither saw their children as being obese nor were they concerned about their children’s weight. However, the pilot program also found that parents demonstrated interest in receiving information on ways to promote healthy behaviors in their families, WIC program staff requested information on effective methods to reach parents, and community groups expressed interest in working on the issue of childhood obesity prevention (USDA, 2005b) (Chapters 6 and 8).

USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service and Agricultural Marketing Service have collaborated with the Department of Defense (DoD) since 1995 through the DoD Fresh Program to supply fresh fruit and vegetable produce directly to school food services to improve school meals (USDA, 2006a). The DoD uses its high volume and effective purchasing and delivery mechanisms to deliver fresh produce to schools, along with military installations and other sites. The DoD Fresh Program, which began in 1995 with 8 states, is now a permanent program that provided fresh produce to schools in 46 states and the District of Columbia in the 2005–2006 school year and which was funded at $50 million in FY 2005; produce is also supplied to over 100 Indian tribal organizations (David Leggett, USDA, personal communication, July 13, 2006; USDA, 2006a).

Another federal effort focused on increasing student consumption of fruits and vegetables in schools is the USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP). In the 2002 Farm Bill, Congress initiated the FFVP that provides schools with the funding to offer fresh and dried fruits and fresh vegetables as snacks to students outside of the regular school meal periods. Initiated in the 2002–2003 school year as a pilot program funded at $6 million in 100 schools in four states (Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Ohio) and seven schools in New Mexico’s Zuni Indian Tribal Organization, the program has since expanded to 14 states and three tribal organizations and legislation has been drafted to expand the program nationwide (Branaman, 2003; Buzby et al., 2003; ERS, 2002; UFFVA, 2006) (Chapter 7). Quantitative outcomes data were not collected in the pilot program, but a qualitative process evaluation suggested satisfaction with the program in many schools and by food service staff (Buzby et al., 2003). An evaluation of 25 schools in Mississippi that participated in the FFVP suggests that the distribution of free fruit to middle school students might be effective as a component of a more comprehensive approach to improve dietary behaviors (Schneider et al., 2006). The committee encourages more extensive evaluations of the FFVP and DoD Fresh Program that examine a variety of relevant outcomes to preventing childhood obesity.

The Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005a) recommended that DHHS develop, implement, and evaluate a long-term national multimedia and public relations campaign focused on obesity prevention in children and youth. Inherent in this recommendation was the need to develop a campaign, in coordination with other federal departments and agencies, and with input from independent experts to focus on building support for obesity prevention policy changes and providing information to parents as well as children and youth. The report emphasized the need for a rigorous evaluation to be a critical component of the campaign; that reinforcing messages be provided in diverse media and effectively coordinated with other events and dissemination activities; and that the media incorporate

obesity issues into its content, including the promotion of positive role models.

The committee acknowledges that as a component of the DHHS Steps to a HealthierUS Cooperative Agreement Program (Steps Program), DHHS partnered with the Ad Council to create SmallStep and SmallStep Kids!, which target parents, teens, and children and which includes public service advertisements (PSAs), a public relations campaign, a health care provider’s tool kit, and consumer information materials. The component targeted to children includes games and activities, television advertisements, and links to other materials. In addition to the advertising components, the Ad Council plans to implement a curriculum-based program with a major educational partner to educate children about the importance of healthy lifestyles and anticipates expanding the program through additional partnerships.

|

BOX 4-5 Case Study of the VERB™ Campaign Background The VERB™ campaign, coordinated by CDC from FY 2001 through 2006, was a 5-year, national, multicultural, social marketing initiative designed to increase and maintain physical activity among 21 million U.S. tweens (children ages 9–13 years) (Huhman et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2004). The national program initially included augmented media in selected markets where local coalitions coordinated community activities to complement the media campaign. Beginning in the second year, national marketing promotions were initiated that invited schools and communities to participate in the campaign. Parents and other intermediaries that influence tweens (e.g., teachers and youth program leaders) were secondary target audiences of the campaign. The VERB campaign is an example of behavioral branding, which raises the awareness of a brand that encourages a behavior or lifestyle such as increased physical activity. The primary goal during the first year of the campaign was to build brand awareness among tweens followed by messaging that encouraged them to find “their verb” and become physically active. All forms of media (e.g., television, print, the Internet) were used to reach tweens of various racial/ethnic groups. The campaign combined paid advertising, modern media marketing strategies, and partnerships to reach the distinct audiences of young people and their adult influencers. Formative Evaluation Before CDC launched the 5-year youth media campaign, VERB—It’s what you do.—it used exploratory research techniques to gain insights into a variety of factors relevant to understanding how to increase and maintain physical activity levels in the multiethnic U.S. tweens. Formative research was conducted with the target group to inform the design of the social marketing campaign. The research showed that tweens would respond positively to messages that promoted physical activities that are fun, occur in a socially inclusive environment and that emphasize self- |

The campaign has received approximately $210 million in donated media support. An evaluation of SmallStep has shown that respondents who had seen at least one of the PSAs were more likely than those who had not seen the campaign to report that they had already changed their diet and physical activity habits (27 percent compared with 14 percent) (Ad Council, 2006). Ongoing support and evaluation of this program are recommended given the potential reach and influence of the media in socializing the public, especially young people. Further, DHHS and its partners should work to further coordinate this campaign and related dissemination activities with other federal agencies. Print, broadcast, and electronic media should include the promotion of positive role models and healthy lifestyles.

However, the CDC’s VERB™—It’s what you do., described in Box 4-5, is an example of a federal program initially funded at scale that even

|

efficacy, self-esteem, and belonging to their peer group (Aeffect, Inc., 2005; CDC, 2006a). Process Evaluation Evaluations have examined process measures to ensure that the campaign was being implemented as planned. A quarterly tracking survey was conducted to assess that the brand and messages continued to appeal to tweens and that the high awareness of the campaign was maintained over time (CDC, 2006d). Outcome Evaluation The cognitive and behavioral outcomes of the VERB campaign have been tracked annually through the Youth Media Campaign Longitudinal Survey (YMCLS). During the first years of the campaign, the level of awareness of the VERB campaign among the target audience was high, and was associated with higher levels of physical activity in tweens who were exposed to and aware of VERB (Huhman et al., 2005, 2007). Evaluation of VERB through FY 2006, monitored through the YMCLS, will allow continued comparison of physical activity levels in tweens who were exposed to the campaign and those who were not exposed (Huhman, 2006). Additionally, surveillance data collected through the YMCLS will be publicly available in 2008 (Faye Wong, CDC, personal communication, August 8, 2006). Lessons Learned Despite evidence of success and widespread knowledge of the importance of physical activity in preventing childhood obesity, there was inadequate support in the administration and Congress for continuing VERB, and insufficient external support to encourage sustained funding. A major challenge for the VERB campaign was to sustain children’s awareness and motivation to be physically active despite the progressive reduction in federal support over its 5-year authorization. Federal funding for the campaign was $125 million in FY 2001, reduced to $68 million in FY 2002, $51 million in FY 2003, $36 million in FY 2004, and increased to $59 million in FY 2005. Over the 5-year period, the average cost of the VERB campaign was $68 million/year. |

with positive evaluation results has not received sustained funding. Multiyear evaluations of VERB were appropriately built into the campaign from its inception. Evaluation of the campaign’s first 2 years demonstrated the program’s effectiveness in raising awareness of the VERB brand and achieving increased free-time physical activity in tweens (Huhman et al., 2005, 2007). However, it was not included in the president’s FY 2006 budget and received no congressional support for continuation beyond FY 2006 because of competing policy priorities. The campaign will be phased out by September 2006 (Huhman, 2006). Evaluation activities will be completed in early 2007 with plans to publish the summative evaluation results of the campaign (Faye Wong, CDC, personal communication, August 8, 2006). The termination of an adequately funded, well-designed, and effective program to increase physical activity and combat childhood obesity calls into question the commitment to obesity prevention within government and by multiple stakeholders who could have supported the continuity of the VERB campaign.

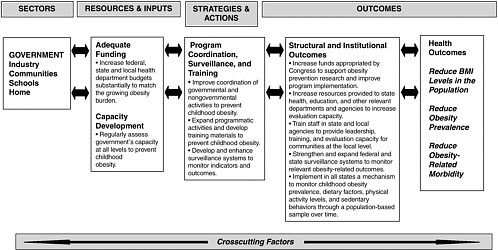

Capacity Development

Capacity building is a multidimensional process that improves the ability of individuals, groups, communities, organizations, and governments to meet their objectives or enhance performance to address population health. In public health, capacity building or capacity development involves the performance of essential functions, such as developing and sustaining partnerships, leveraging resources, surveillance and monitoring, providing training and technical assistance, and conducting evaluations. It is a function of the size, training, and experience of the workforce and the resources available to the workforce to accomplish the task (IOM, 2003).

The Health in the Balance report recommended that the federal government support nutrition and physical activity grant programs, particularly in states with the highest prevalence of childhood obesity (IOM, 2005a). Although specific definitions and measures of the capacities of federal, state, and local governments to adequately carry out the activities necessary to halt and reverse the childhood obesity epidemic are not readily available, the committee concluded that existing evidence suggests serious shortfalls. Recent surveys conducted by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists noted that the epidemiologic capacity for terrorism preparedness and emergency response had increased between 2001 and 2004, whereas capacities in six other areas, including the capacity for epidemiologic analysis of chronic diseases, had decreased, with less than half of the states reporting that they had a substantial capacity for the epidemiologic analysis of chronic diseases (CDC, 2005b; CSTE, 2004). The Health in the Balance report recommended that the federal government should support nutrition

and physical activity grant programs, particularly in states with the highest prevalence of childhood obesity (IOM, 2005a).

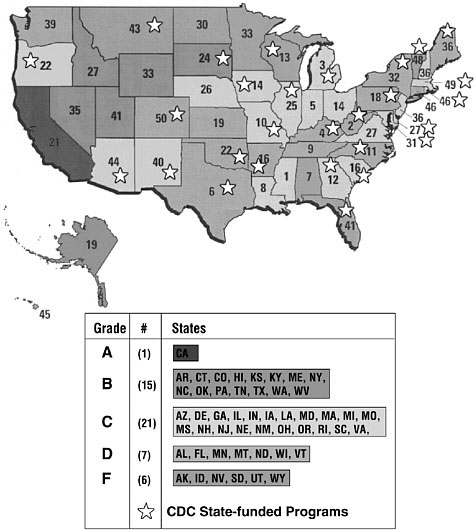

Nutrition and Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases

CDC’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases is an example of a federal initiative designed to build the capacity of states to prevent obesity in adults, children, and youth. In 2005 and 2006, a total of 28 states received funding under this program: 21 states received funding of $400,000 to $450,000 for capacity development and seven states (Colorado, Massachusetts, North Carolina, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington) received funding of $750,000 to $1.3 million for basic implementation (CDC, 2006b). CDC has provided technical assistance and tools to help all states develop and evaluate their obesity prevention strategic plans (Yee et al., 2006). The states have hired approximately 130 individuals to work on the strategic plans, and CDC has hired staff to provide program oversight and technical assistance to the states (CDC and RTI, 2006). This initiative was first funded in FY 2000, and appropriations grew from $1.6 million in FY 2000 to $16.2 million in FY 2005 and declined slightly to $16.0 in FY 2006 (Table 4-2). Despite applications from nearly every state, the relatively stable level of funding since FY 2004 has limited the expansion of this program to other states. An assessment is needed to identify the appropriate level of funding required to support all states and territories in capacity building and program implementation to prevent obesity.

TABLE 4-2 CDC’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of States Funded |

Funding ($ million) |

|

2000 |

6 |

$ 1.6 |

|

2001 |

12 |

$ 4.0 |

|

2002 |

12 |

$ 5.6 |

|

2003 |

20 |

$ 9.7 |

|

2004 |

28 |

$14.6 |

|

2005 |

28 |

$16.2 |

|

2006 |

28 |

$16.0 |

|

SOURCE: Robin Hamre, NCCDPHP/CDC, personal communication, July 27, 2006. |

||

A process evaluation of the efforts in 28 of the CDC-funded states has been conducted. The evaluation focuses on policies, legislation, and environmental changes affecting nutrition and physical activity, implementation and coordination, and the inclusion of relevant partners. The evaluation found that the funded states had successfully involved partner organizations in planning and implementing interventions and cosponsored events aimed at improving body mass index (BMI) in children and adults; however, the evaluation also revealed potential service gaps, overlap with other programs aimed at preventing and controlling obesity, opportunities for additional services, and potential barriers to delivering services (CDC and RTI, 2006).

Steps to a HealthierUS Program

The Steps to a HealthierUS Program, initiated in 2003 by DHHS and administered by CDC, is another federal program intended to increase the capacity of local public health systems to address chronic health concerns. The Steps Program enables communities to develop an action plan, a community consortium, and an evaluation strategy that supports chronic disease prevention and health promotion to lower the prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and asthma through healthful eating, physical activity, and tobacco avoidance in disproportionately affected, at-risk and low-income populations including African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders (DHHS, 2005b,c). The Steps Program funds communities in three categories: large cities or urban areas, state-coordinated small cities or rural areas, and tribes or tribal entities. Initially funded at $13.6 million in FY 2003, during FY 2004 to FY 2006 the Steps Program received $35.8 million per year to support 40 communities nationwide. Aside from financial resources, CDC provides capacity through technical assistance to support evidence-based program planning and implementation, disease and risk factor surveillance, and program evaluation with the 40 funded communities participating in the annual BRFSS and biennial Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). The allocation of resources to support both surveillance and evaluation comprises 10 percent of the total program funding in the majority of the funded communities (MacDonald et al., 2006).

The Steps Program uses indicators developed by CDC that provide a comprehensive set of measures for assessing programs in chronic disease prevention and health promotion. The most relevant indicators related to nutrition and physical activity among youth include fruit and vegetable consumption, vigorous physical activity, television viewing, and monitor-

ing of obesity prevalence (CDC, 2004). The Steps Program uses data from the BRFSS and YRBSS to monitor the progress that has been made in achieving behavioral and health outcomes at national and community levels (MacDonald et al., 2006). An evaluation of the 40 Steps Program communities funded nationwide is in progress.

Food Stamp Nutrition Education Program

USDA’s Food Stamp Nutrition Education (FSNE) program is an example of a federal innovation that encourages collaboration and that leverages resources. FSNE allows states to create social marketing networks, mobilize other organizations, and join efforts to conduct interventions with low-income participants to achieve healthier eating patterns and increased physical activity levels (Gregson et al., 2001; Hersey and Daugherty, 1999). Some states also encourage policy, systems, and environmental changes that increase access to foods and beverages that contribute to healthful diets and physical activity in low-income communities. Schools with limited resources are a common setting used by FSNE. In 2005, nearly all state Food Stamp Programs (FSP) submitted annual FSNE plans that qualified for federal financial participation funds, whereas only a decade earlier only seven states had done so. A review of state FSNE is near completion.

HealthierUS School Challenge

USDA’s HealthierUS School Challenge is a more recent USDA initiative aimed at encouraging positive changes by recognizing schools that are creating a healthy environment. To qualify, elementary schools must enroll in Team Nutrition, conduct school assessments, provide lunches that meet specific nutrient requirements, offer physical activity, and achieve 70 percent participation in NSLP. Recognition programs such as these could help in disseminating promising practices; however, it is important that the efforts be disseminated broadly to media, parent-teacher associations, and others to provide incentive for schools to participate.

Further Efforts

It has been recommended that USDA improve coordination and strengthen linkages among its nutrition education efforts (GAO, 2004a), and state nutrition action plans are now required for USDA food and nutrition assistance programs. The committee encourages further efforts to develop policies that foster opportunities for collaboration among USDA programs relevant to childhood obesity prevention.

National Surveillance, Monitoring, and Research

Surveillance and Monitoring

Public health surveillance is the ongoing systematic process of collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and using data from generalizable samples that pertain to the public’s health. Surveillance systems provide ongoing assessments of changes and trends related to public health concerns and provide evidence of the combined effect of all actions taken to address the concern. They can be viewed as an evaluation of the overall system, but surveillance systems rarely provide sufficient information about the factors that cause the changes to serve as the primary tools of evaluation.

The Health in the Balance report included the following recommendations related to surveillance (IOM, 2005a):

-

Support for relevant surveillance and monitoring systems, especially NHANES, should be strengthened;

-

FTC should monitor industry compliance with food and beverage and sedentary entertainment advertisement practices; and

-

All school meals programs should meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (DHHS and USDA, 2005).

Examples of federal surveillance activities that are conducted by CDC and that are used to monitor selected indicators and behavioral outcomes relevant to obesity in children and youth at national or state levels include (1) NHANES, which assesses the health and nutritional status of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, youth, and children through interviews and a direct physical examination; (2) the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which is conducted annually and which assesses physical activity, health care access, and health care coverage for household members; (3) the Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System (PedNSS), which collects data on health care and health status of low-income children, especially participants in the WIC program; (4) the Youth Media Campaign Longitudinal Survey (YMCLS), which is used to track older children’s physical activity levels and media use, and to evaluate the VERB campaign; and (5) the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), which was initiated in 1991 as a system of national, state, and local school-based surveys conducted biennially. YRBSS obtains self-reported information about six categories of health-related behaviors, including dietary and physical activity behaviors for students in grades 9 to 12. Since 1999, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) has included self-reported height and weight, from which the BMI is calculated. Although NHANES uses directly measured

height and weight, it provides only national estimates, whereas YRBS provides national, state, and city data only for those participating and only those organizations that have the capacity to administer the survey. A national YRBS is not conducted with students in grades 6 to 8. The most current YRBSS summarizes the results from the national survey, 40 state surveys, and 21 local surveys conducted with students in grades 9 to 12 from 2004 to 2006 (Eaton et al., 2006).

Other national surveillance systems include the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DoL’s) National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), which has provided data on income and BMI for two youth cohorts since 1979 and 1997 (DoL, 2006); the American Community Survey, which is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006); and the National Household Travel Survey (NHTS), which is conducted by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics and the Federal Highway Administration to assess motorized and nonmotorized travel (BTS, 2006). Federally funded surveillance and monitoring systems also examine changes in policies and programs. Examples include the School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS) and the School Health Profiles (SHP) survey. A more detailed description of these surveys is found in Chapter 7 and Appendixes C and D. Given the urgency of the childhood obesity epidemic, it is important to conduct frequent assessments of changes in the school environment. For example, USDA’s School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study (SNDA), which provides information about the nutritional quality of meals served in public schools that participate in the school meals programs (USDA, 2001), was conducted in the 1991–1992 and 1998–1999 school years, and a report on the most recent SNDA is anticipated in fall 2006. Adequate funding and expansion of this survey is needed to ensure ongoing and regularly scheduled assessments. Additionally, the committee recommends that USDA explore other approaches for tracking and monitoring the nutritional quality, monetary sales, and levels of consumption of foods and beverages sold in schools.

An assessment has been conducted to identify national data systems that could track the outcomes of USDA food assistance and nutrition programs (Biing-Hwan et al., 2006). At present, however, no reporting systems are in place to identify how the precursors of childhood obesity are being addressed in the populations, organizations, and communities served by the WIC program, FSP, or the school meals programs. Examples of outcome measures that could be monitored include the degree to which individual hunger and household food insecurity are reduced by FSP and whether the recommended performance-based school meals reimbursement system provides incentives for the NSLP meals to meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (OMB, 2005).

USDA, in collaboration with other stakeholders, has opportunities to assist states and localities by improving surveillance and monitoring capacity to fill essential data gaps. Some larger state WIC programs have developed reporting systems that could help identify effective approaches to address obesity in young children (National WIC Association, 2003). For example, new state registries for school wellness policies could be used to track progress toward achieving important obesity-related national goals. FSNE state systems that monitor the outcomes of programs at the state and local levels might be tapped for adoption nationwide. Such actions would require administrative decisions but not statutory changes. For example, USDA could allow the WIC program to invest in computers or permit FSNE to fund surveys of individuals with incomes above 130 percent of the federal poverty level. For the WIC program, many large states already have made the investment in computers, so automation in smaller states could be offered at a modest incremental cost. These opportunities could improve the monitoring of the effectiveness of USDA interventions and programs (USDA, 2006c).

As noted earlier, both BRFSS and NHANES were the first surveillance systems to document the growing obesity epidemic in U.S. adults and children (Flegal et al., 2002; Hedley et al., 2004; Mokdad et al., 1999; Ogden et al., 2002, 2006; Troiano et al., 1995). The NHANES and NHIS are administered through CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); and BRFSS, YRBSS, SHP, and SHPPS are administered through CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). The funding for these surveillance systems in FY 2001 and FY 2005 is provided in Table 4-3.

Comparison of the FY 2001 and FY 2005 budgets for NHIS and NHANES reveals a relatively flat funding structure to support these two important national surveillance systems1 (Edward Hunter, NCHS/CDC, personal communication, June 28, 2006). Similarly, federal funding levels have been static for other surveillance systems, including YRBSS, SHP, PedNSS, and Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance System (PNSS). The only survey that showed a marked increase in funding during this time frame was BRFSS, which was due to a congressional appropriation of $5 million in FY 2003 and small incremental increases until FY 2005. These increases occurred so that Congress could rectify the funding gap between BRFSS expenses and the congressional funding line. Even with these increases, BRFSS has never been fully funded; thus, funds from other categorical

TABLE 4-3 CDC Surveillance Systems Funding

|

|

FY 2001 ($ million) |

FY 2005 ($ million) |

|

NHANES |

21.0 |

20.5 |

|

NHIS |

12.9 |

15.4 |

|

BRFSS |

1.92 |

7.64 |

|

YRBSS |

1.96 |

2.5 |

|

SHP |

0.712 |

0.767 |

|

SHPPS |

data unavailable |

1.74 |

|

PedNSS and PNSS |

0.248 |

0.274 |

|

SOURCES: Edward Hunter, NCHS/CDC, personal communication, June 28, 2006; NCCDPHP/CDC Financial Management Office, personal communication, July 17, 2006. |

||

awards and from state budgets are used to fully fund this surveillance system (NCCDPHP/CDC, Financial Management Office, personal communication, July 17, 2006).

A sufficient investment in health statistics and surveillance systems is essential to track a national public health crisis such as the obesity epidemic. Although these funds have been used to increase sample sizes necessary for these surveys and to provide information on population subgroups, including children and youth (DHHS, 2006), the committee concluded that substantial funding increases are needed not only to ensure the continuation of these important surveillance systems but also to enhance and expand data collection for the range of outcomes relevant to the childhood obesity epidemic.

Research

Conducting and supporting obesity-related research are important governmental functions (IOM, 2003). Research helps provide an understanding of the fundamental and intermediate causes of childhood obesity and the determinants of and the relationships between eating and physical activity behaviors. Research also helps to refine theories about behavioral change that are necessary for the development of effective programs and promising practices. Ongoing research is examining the developmental changes of children and youth and the risk and protective factors that affect vulnerable periods during the life course relevant to childhood obesity. Given the complex interplay among environmental, social, economic, and behavioral factors that influence childhood obesity, considerably more research is necessary to inform an adequate and comprehensive response to the obesity epidemic.

In 2005, the Federal Interagency Working Group on Overweight and Obesity Research was formed to strengthen federal leadership in the area of obesity research. The working group is cochaired by the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy, DHHS, and USDA (Appendix D). Its purpose is threefold: to facilitate constructive, coordinated research across diverse federal agencies and departments; identify areas in which interagency collaboration can extend progress in obesity prevention; and advise OSTP’s Committee on Science about the research needs and opportunities related to overweight and obesity and associated adverse health effects (NSTC, 2006). The intent of the working group is not to duplicate the research initiatives of other federal agencies, such as the NIH Obesity Research Task Force (see below); rather, it is intended to enhance and strengthen the total federal research effort by interdepartmental collaboration (Yanovski, 2006). The working group is in its initial phases, and its efforts have not yet been evaluated. The working group could serve as a component of the broader federal coordinating task force described earlier in this chapter.

The NIH Obesity Research Task Force was established in FY 2003 to accelerate progress in obesity research across the NIH institutes, centers, and offices and is another example of federal leadership in research. An important charge to the task force was the development and implementation of a Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research (Spiegel and Alving, 2005), the coordination of obesity-related research activities across NIH, and the development of new research efforts (NIH, 2004; Spiegel and Alving, 2005). The Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research focuses on goals for basic, clinical, and population-based obesity research and has the following strategies for achieving the goals:

-

Identify modifiable behavioral and environmental factors that contribute to the development of obesity in children and adults through research for the prevention and treatment of obesity through lifestyle modification;

-

Identify genetic factors and biologic targets related to obesity and identify pharmacologic, medical, and surgical approaches for preventing and treating obesity; and

-

Identify the connections between obesity and type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and other diseases and approaches for addressing these chronic conditions.

The strategic plan focuses on enhancing crosscutting research by encouraging interdisciplinary research teams; focusing on specific populations such as children and racial/ethnic minorities; conducting translational research that progresses from basic science to clinical studies, trials, and

community interventions; and disseminating research results to the public (NIH, 2005).

It is unclear what proportion of the NIH research effort is dedicated to obesity prevention research and what proportion is dedicated to clinical research on treatment methods or basic research on the endocrine or metabolic mechanisms of obesity. To achieve the strategic plan’s goals, activities must be coordinated among the NIH institutes, offices, and centers. Effective coordination has been identified as a formidable challenge for the implementation of other NIH strategic plans, including the Health Disparities Research Program, because of the research’s scope and complexity and NIH’s organizational and functional setting (IOM, 2006b). The committee’s perspective is that similar challenges exist for effectively coordinating the Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research.

CDC’s Prevention Research Center (PRC) programs also play an important role in obesity prevention research. The 33 currently funded PRC programs have established academic and community-based partnerships that collaboratively conduct research addressing the immediate health needs of communities. The community and university research partners identify the successful aspects of projects that can be disseminated to other communities (CDC, 2006c). Seven PRCs have projects that focus on obesity prevention such as Preventing Obesity in the United States. Other projects are Guidelines for Obesity Prevention and Control (Yale University), Adapting the Coordinated Approach To Child Health (CATCH) for Obesity Prevention and Control (University of Texas at Houston), Planet Health—A Health Education Program for School Children (Harvard University), Dietary Contributions to Obesity and Adolescents (Harvard University), and Impact of Neighborhood Design and Availability of Public Transportation on Physical Activity and Obesity Among Chicago Youths (Harvard University) (CDC, 2006c). A network of PRCs, referred to as the Physical Activity Policy Research Network, is collaborating to study policies and policy development pertaining to physical activity. Additionally, 7 PRCs and 12 state health departments are collaborating with the Center for Weight and Health at the University of California at Berkeley to review the dietary and developmental influences on obesity (Woodward-Lopez et al., 2006).

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

The Health in the Balance report called for state and local governments to implement the report’s recommendations through the provision of coordinated leadership and support for childhood obesity efforts, particularly those focused on high-risk populations, by increasing resources and strengthening policies that promote opportunities for healthful eating and physical activity

in communities, neighborhoods, and schools (IOM, 2005a). It encouraged the provision of support for public health agencies and local coalitions in their collaborative efforts to promote and evaluate obesity prevention interventions. State and local government agencies have traditionally and constitutionally been the primary overseers and implementers of public health activities. The important functions of state and local governments mirror those of the federal government and include leadership; the provision of program resources, funding, and evaluation; the conduct of statewide and local surveillance, monitoring, and research; and the dissemination and use of the evidence resulting from evaluations.

Leadership

Many states and communities throughout the nation are providing leadership through focused efforts to increase opportunities for physical activity and improve the dietary intake of children and youth. The National Governors Association made obesity prevention a priority as early as 2002 and has established a bipartisan task force of governors to provide further direction on this issue (NGA, 2003, 2006). As administrators of state programs, governors are in a central position to promote the societal norms and a culture that supports physical activity, healthful eating, and obesity prevention in their states (NGA, 2006). The Council of State Governments has developed a tool kit for policy options to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent obesity in youth (CSG, 2006).

Obesity prevention was also identified as a priority for local governments in a resolution at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the U.S. Conference of Mayors, which encouraged and supported local leadership through the implementation of policies, public health programs, and partnerships, including a focus on under-represented, low-income, and socially disadvantaged populations (USCM, 2004).

Several states have developed action plans focused on reducing obesity in children, youth, and adults. Many of these plans were developed through the collaborative efforts of voluntary health organizations, state agencies, nonprofit organizations, and health plans and other business partners (e.g., Georgia Department of Human Resources and Division of Public Health, 2005; North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2005; West Virginia Healthy Lifestyle Coalition, 2005). Some plans originated with the action of a state agency to convene stakeholders, whereas other plans coalesced under the leadership of a nonprofit organization and then became an integral part of the state effort. In Texas, for example, the state strategic plan includes measurable objectives and sector-specific strategies for families, schools and child-care centers, communities, worksites, the

health care sector, local businesses and private industry, and state government (Texas Statewide Obesity Taskforce, 2003).

As states and local governments work to develop and implement action plans, it is important that they sustain an active task force or standing committee to coordinate and oversee the efforts related to preventing childhood obesity. Task forces or committees function in ways that are appropriate for state and local conditions and practices, in general, and are expected to coordinate and leverage resources, ensure the capacity of government agencies to conduct surveillance and monitoring of programs, and ensure that childhood obesity prevention activities are appropriately evaluated at all levels.

In September 2005, the California Governor’s Summit for a Healthy California brought together a diverse group of stakeholders to discuss the next steps for obesity prevention and health promotion in the state as outlined in a 10-point vision for healthy living (Box 4-6). Strategic planning efforts are under way to follow through on the actions discussed at the summit (Strategic Alliance, 2005) (Appendix F).

A number of states and communities have introduced or adopted bills and resolutions that represent legislative and policy actions related to childhood obesity prevention (Boehmer et al., 2006; TFAH, 2005) (Table 4-4).

|

BOX 4-6 A Vision for California—10 Steps Toward Healthy Living

SOURCE: California Health & Human Services Agency and The California Endowment (2005). |

TABLE 4-4 State Legislation Relevant to Childhood Obesity, 2003–2005

|

Topic |

Description |

Billsa # adopted/ # introduced (% adopted) |

Resolutionsb # adopted/ # introduced (% adopted) |

|

School Environment |

|||

|

Nutrition Standards, Vending Machines |

Provide students with nutritious food and beverage items. Restrict access to vending machines and competitive foods. Regulate marketing of foods and beverages with minimal nutritional value. Report nutritional information and vending machine revenue. |

27/213 (13%) |

9/25 (36%) |

|

Physical Education, Physical Activity |

Ensure that schools have a physical education (PE) program. Set time and frequency for PE classes. Restrict substitutions and waivers for PE. Promote physical activity in other classes. |

26/165 (16%) |

14/26 (54%) |

|

Health Education |

Ensure that schools include nutrition, physical activity, and obesity prevention in health education curriculum. |

12/68 (18%) |

3/5 (60%) |

|

Curriculum for Health and Physical Education Classes |

Govern changes to the state’s curriculum related to health, nutrition, and physical education. Require set hours of PE per week. Establish graduation requirements. |

9/61 (15%) |

2/7 (29%) |

|

Local Authority |

Provide local districts with the ability to set policies and create committees that focus on reducing the prevalence of obesity among school-age children through the regulation of low-nutrient food and beverages and physical activity requirements. |

12/58 (21%) |

1/4 (25%) |

|

Safe Routes to School |

Provide bicycle facilities, sidewalks, crossing guards, and traffic-calming measures to enable children to bicycle or walk safely to school. |

12/43 (28%) |

3/4 (75%) |

|

Body Mass Index (BMI) |

Require or allow schools to measure, monitor, and report student’s BMI in conjunction with intervention strategies to help reduce childhood obesity. |

8/37 (50%) |

1/2 (22%) |

|

Model School Policies |

Require state agencies or state education officials to develop model school policies relating to nutrition and physical education. |

4/14 (29%) |

1/1 (100%) |

|

Topic |

Description |

Billsa # adopted/ # introduced (% adopted) |

Resolutionsb # adopted/ # introduced (% adopted) |

|

Community Environment |

|||

|

Study/Council/ Task Force |

Establish a commission, committee, council, task force, or study to address obesity within schools or communities. |

11/68 (16%) |

15/42 (36%) |

|

Farmers’ Markets |

Support and make appropriations for farmers’ market initiatives. Promote the implementation of locally grown nutritious foods in school systems. |

31/87 (36%) |

3/3 (100%) |

|

Statewide Initiative |

Establish initiatives, often though the state’s department of health, to reduce the prevalence of obesity among residents statewide. |

11/37 (30%) |

28/35 (80%) |

|

Walking/ Biking Paths |

Support (through appropriations and regulations) physical activity through the creation or maintenance of bicycle trails, walking paths, and sidewalks. Promote bicycle and pedestrian safety. |

17/46 (37%) |

2/2 (100%) |

|

Soda and Snack Tax |

Increase or establish a tax on snacks and soft drinks. May use revenue to promote nutrition and health in schools. |

0/49 (0%) |

0/0 (0%) |

|

Restaurant Menu and Product Labeling |

Regulates the labeling of nutrition content on food items. Requires restaurants to post nutritional information on menus. |

0/25 (0%) |

0/0 (0%) |

|

Totalc |

|

123/717 (17%) |

71/134 (53%) |

|

aA bill is a proposed law or amendment to an existing law that is presented to a state legislature for consideration. A bill requires approval by both chambers of the legislature and action by the governor in order to become law. bA resolution is a formal expression of the will, opinion, or direction of one or both houses of the state legislature on a matter of public interest. Joint and concurrent resolutions are voted on by both houses but require no action on the part of the governor. Typically, resolutions are temporary in nature and do not have the power of law. cNumbers and percents do not add up to the total because some bills and resolutions were listed in more than one topic area. SOURCE: Adapted from Boehmer et al. (2006). |

|||

Many of these efforts are primarily focused on changing the school environment. However, there are some proposals relevant to childhood obesity prevention through its influence on communities (e.g., establishing farmers’ markets, creating walking or bike paths, supporting smart growth, preserving green spaces, and addressing urban sprawl issues and industry (e.g., restaurant menu and product labeling, proposing taxes on soda or snack foods) (Boehmer et al., 2006; TFAH, 2005).

State legislation specific to schools has largely been focused on establishing nutritional standards for school foods, with growing attention being paid to mandating physical activity standards (Chapter 7). For example, legislation and regulations in Texas have mandated a minimum number of minutes of physical education for students in elementary, middle, and junior high schools; created local school health advisory councils; and established nutritional requirements for foods, beverages, and meals served in schools (TAHPERD, 2006; Texas Department of Agriculture, 2003). Arkansas Act 1220 was enacted in 2003 and included several school-related mandates, such as eliminating access to vending machines in public elementary schools, disclosing contracts for competitive foods and beverages, conducting annual BMI assessments for all students, and establishing nutrition and physical activity advisory committees to develop local policies (Ryan et al., 2006). The committee encourages the states to develop accountability mechanisms that provide the general public with information on the extent to which schools are meeting obesity prevention standards and evaluation results of innovative obesity prevention programs. Additionally, the committee supports increased legislative and other state and local government actions that will facilitate childhood obesity prevention efforts at the community, regional, and state levels.

Program Resources and Evaluation

Many state and local agencies have essential roles to play in designing, funding, implementing, and evaluating effective programs to support childhood obesity prevention goals. The obesity prevention efforts of local governments are complementary to those of the state and federal governments. In particular, local public health departments are involved in providing leadership for the horizontal integration of interventions, communications, and funding requirements, as well as developing an adequate infrastructure in which policies and programs can be implemented and evaluated at the local level.

Horizontal integration is a useful public health approach that encourages partners at the same level of operation—the neighborhood, city, county, regional, or state level—to work across organizational lines to deliver consistent, comprehensive, and multicomponent interventions. Examples of hori-

zontal integration are the coordination of obesity prevention interventions through a local WIC program, a community youth agency, and a local business or a corporate-sponsored community-based program. Vertical integration is also used when partners work at different levels—the national, regional, state, county, and community levels—to deliver interventions planned at a higher level and delivered at a lower level in a coordinated way. The use of both the vertical and the horizontal integration approaches allow maximum synergy to facilitate effective collaboration.

The USDA’s State Nutrition Action Plans have promoted horizontally and vertically integrated efforts across agency lines by local health departments, school districts, county extension agencies, and social service departments (USDA, 2006c). For example, the members of the Florida Interagency Food and Nutrition Agency include the Florida Department of Children and Families, the Department of Health, the Department of Education, the Department of Agriculture, and Consumer Services, among others, that coordinate nutrition campaigns and activities (FIFNC, 2006). Utah’s Blueprint to Promote Healthy Weight for Children, Youth, and Adults addresses actions by families, schools, communities, worksites, health care, media, and government that are needed including forming a team of leaders to assume active roles in addressing issues of overweight and obesity (Bureau of Health Promotion, 2006).

At times, however, the division of authority among governments at the federal, state, and local levels has led to inconsistencies, ineffective resource allocation, and uncertainty about the respective roles and responsibilities of the units at each level that is challenging for the task of effective coordination (Baker et al., 2005; TFAH, 2006). A sustained effort that includes adequate planning and cooperation among governmental agencies and departments and other stakeholder groups is needed so that the units at each of these levels can effectively work together.

In addition, the overall capacity to address childhood obesity is not enhanced when increases in federal funding are responded to by decreases at the state level. Current funding for obesity prevention is also often tied to funding for other public health issues; thus, decision makers at the state and local levels are challenged by coordinating funds from a variety of funding strategies and sources (Finance Project, 2004).