5

Industry

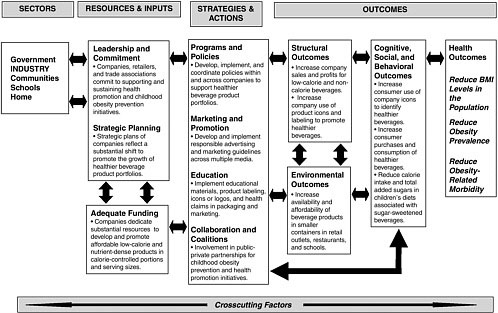

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Health in the Balance report presented a set of comprehensive recommendations to guide industry’s collective actions to support childhood obesity prevention goals (IOM, 2005). The report recommended that industry prioritize obesity prevention in children and youth by “developing and promoting products, opportunities, and information that will encourage healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity.” The report also recommended that “industry should develop and strictly adhere to marketing and advertising guidelines that minimize the risk of obesity in children and youth” (IOM, 2005, p. 166). The development of clear and useful nutrition labeling was a third area in which the report offered guidance to industry and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) so that they may help parents and youth make informed purchases in the marketplace and select foods, beverages, and meal options that contribute to healthful diets (Box 5-1) (IOM, 2005).

After the release of the Health in the Balance report, another IOM committee released a related report, Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity?, which provides findings on the influence of marketing on children’s and adolescents’ food and beverage preferences, choices, purchase requests, dietary practices, and health-related outcomes (IOM, 2006). It also offers expanded recommendations for numerous industry stakeholders including food retailers, trade associations, entertainment companies, food and beverage companies, restaurants, and the media (Box 5-2).

This chapter explores the current and potential strategies that industry stakeholders use or could use to make progress toward meeting the recommendations made in those reports. The chapter provides examples of

|

BOX 5-1 Recommendations for Industry from the 2005 IOM report Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance Industry should make obesity prevention in children and youth a priority by developing and promoting products, opportunities, and information that will encourage healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity. To implement this recommendation:

Industry should develop and strictly adhere to marketing and advertising guidelines that minimize the risk of obesity in children and youth. To implement this recommendation:

Nutrition labeling should be clear and useful so that parents and youth can make informed product comparisons and decisions to achieve and maintain energy balance at a healthy weight. To implement this recommendation:

SOURCE: IOM (2005). |

|

BOX 5-2 Recommendations from the 2006 IOM Report Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? Food and beverage companies should use their creativity, resources, and full range of marketing practices to promote and support more healthful diets for children and youth. To implement this recommendation, companies should:

Full serve restaurant chains, family restaurants, and quick serve restaurants should use their creativity, resources, and full range of marketing practices to promote healthful meals for children and youth. To implement this recommendation, restaurants should:

Food, beverage, restaurant, retail, and marketing industry trade associations should assume transforming leadership roles in harnessing industry creativity, resources, and marketing on behalf of healthful diets for children and youth. To implement this recommendation, trade associations should:

|

The food, beverage, restaurant, and marketing industries should work with government, scientific, public health, and consumer groups to establish and enforce the highest standards for the marketing of foods, beverages, and meals to children and youth. To implement this recommendation, the cooperative efforts should:

The media and entertainment industry should direct its extensive power to promote healthful foods and beverages for children and youth. To implement this recommendation, media and the entertainment industry should:

SOURCE: IOM (2006). |

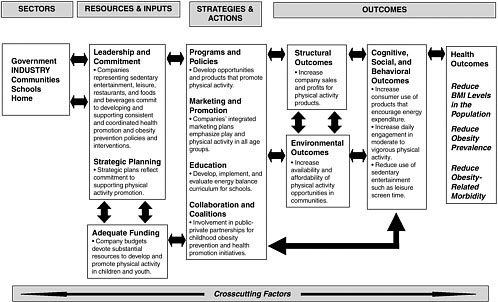

current private-sector efforts that support obesity prevention, including the efforts of food and beverage manufacturers; full serve restaurants and quick serve restaurants (QSR);1 food retailers; trade associations; the media; corpo-

rate and private foundations; and the leisure, recreation, and sedentary entertainment industries. The strategies that industry uses to address childhood obesity prevention include product development and reformulation, product packaging, enhancing physical activity opportunities, advertising and marketing communications, public-private partnerships, employee wellness initiatives, and corporate social responsibility and public relations.2 The chapter discusses the challenges in assessing the progress made by the private sector and recommends next steps for strengthening evaluation efforts.

A substantial amount of the discussion in this chapter focuses on the food, beverage, and restaurant industries, with fewer examples from the physical activity, leisure, recreation, and sedentary entertainment industries. This imbalance in coverage is due in part to the attention that has been placed on the responses to the obesity epidemic by the food, beverage, and restaurant industries. It is also possible that the segments of industry whose efforts are directly or indirectly related to changing physical activity behaviors may not perceive themselves to be part of the obesity prevention discourse or they may not want to be a focus of attention for this issue. Although a number of corporations are actively engaged in increasing opportunities for physical activity, there is need for further involvement. The committee also benefited from the work of the prior IOM committee on food marketing but did not have a similar compendium of recent efforts related to physical activity. A comprehensive review of the efforts by the physical activity, leisure, recreation, and sedentary entertainment industries3 is needed, as there are many opportunities to increase and coordinate actions within and across this sector to promote physical activity among children and youth.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

In December 2005, the committee held a symposium in Irvine, California that focused on the efforts by industry to engage in and contribute to childhood obesity prevention (Appendix H). This IOM symposium explored the challenges and opportunities that exist in forging alliances between the public health community and industry. Acknowledging the po-

|

2 |

A list of acronyms and a glossary of definitions are provided in Appendixes A and B. Box 5-3 provides the definitions of common marketing terms. |

|

3 |

Examples of active leisure and recreation industries include companies that promote sporting goods, fitness, gyms, and dance. Sedentary entertainment requires minimal physical activity. Examples of sedentary entertainment industries include companies that promote spectator sports, broadcast and cable television, videogames, DVDs, and movies (IOM, 2006; Sturm, 2004). |

tential tension among stakeholder groups, it is important to nurture and strengthen partnerships supporting obesity prevention efforts by

-

Conveying consistent, appealing, and specific messages to children, adolescents, and adults;

-

Ensuring transparency through the sharing of data between the public health community and industry;

-

Making long-term commitments to obesity prevention;

-

Ensuring company-wide commitments (large corporations in particular need to ensure that the entire organization and not just isolated sectors of the business is engaged in obesity prevention efforts);

-

Balancing the free market system with protecting children’s health. While public health advocates acknowledge the values and realities of the competitive marketplace and recognize that many companies are making positive changes, companies should accept responsibility for engaging in marketing practices that promote healthy lifestyles for children and youth;

-

Understanding the interactions between companies, marketing practices, and consumer demand;

-

Exploring potential avenues of impact. One area that has not been fully examined is the potential impact that business leaders can have in advocating for policy changes and initiatives that promote improvements in diet and increased levels of physical activity; and

-

Making a commitment to monitor and evaluate efforts.

UNDERSTANDING THE MARKETPLACE

Companies use a variety of integrated marketing strategies to influence consumer preferences, stimulate consumer demand for specific products, increase sales, and expand their market share. Integrated marketing is a planning process designed to ensure that all promotional activities of a company—including media advertising, direct mail, sales promotion, and public relations—produce a unified, customer-focused promotion message that is relevant to a customer and that is consistent over time. The allocation of companies’ marketing budgets differs on the basis of the nature and the size of the company. Food companies usually spend approximately 20 percent of their total marketing budgets for advertising, 25 percent for consumer promotion, and 55 percent for trade promotion (GMA Forum, 2005; IOM, 2006) (Box 5-3). The committee had no data with which it could assess how the leisure, recreation, and entertainment industries allocate their marketing budgets.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which tracks trends in

|

BOX 5-3 Industry Definitions Marketing A set of processes for creating, communicating, and delivering value to customers and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit an organization and its stakeholders. Marketing encompasses a wide range of activities including conducting market research; analyzing the competition; positioning a new product; pricing products and services; and promoting products and services through advertising, consumer promotion, trade promotion, public relations, and sales. All of these activities are integral tools used by companies in the marketplace that can be potentially directed toward healthier products, diets, and lifestyles. Advertising Advertising represents the paid public presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services by a company or sponsor and is intended to bring a product to the attention of consumers through various media channels. It is often the most recognizable form of marketing. Consumer Promotion Consumer promotion is a marketing activity distinct from advertising. It is also referred to as “sales promotion” and represents companies’ promotional efforts that have an immediate impact on sales. Examples of consumer or sales promotion include coupons, discounts and sales, contests, point-of-purchase displays, rebates, gifts, incentives, and product placement. Trade Promotion Trade promotion is a type of marketing that targets intermediary industry stakeholders such as supermarkets, grocery stores, convenience stores, and other food retail outlets. Examples of trade promotion strategies include in-store displays, agreements with retailers to provide specific shelf space and product positioning, free merchandise, and sales contests to encourage food wholesalers or retailers to sell more of a specific company’s branded products or product lines. Public Relations Public relations are a company’s communications and relationships with various groups including customers, employees, suppliers, stockholders, government, and the public. Proprietary Data Proprietary data consist of information obtained from private companies or firms that hold the exclusive rights to distribute those data, which are often collected for specific commercial purposes intended for a targeted audience. They may be available to customers who can purchase the data, and are usually not widely available to the public due to the expense. SOURCES: AMA (2005); Boone and Kurtz (1998); IOM (2006). |

food and beverage marketplace expenditures, estimated that in 2005, total food and beverage sales in the United States were $1.023 trillion. The growth in food expenditures has been steady since 1967, with a growth of nearly 6.4 percent per year (ERS/USDA, 2006).4 Between 1987 and 2001 there was also considerable growth in the industries associated with leisure and recreation (e.g., sporting goods, spectator sports, and entertainment) (Sturm, 2004), but the committee was unable to find recent data that accurately quantified the total expenditures made by these industries.

In 2004, marketing expenditures for all products—including food, beverages, and other manufactured items—totaled $264 billion, which included $141 billion for advertising in measured media5 (Brown et al., 2005). The IOM Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth found that corporations spent more than $10 billion in 2004 to advertise foods, beverages, and meals to children and youth, of which $5 billion of the total was for television advertising (IOM, 2006). The total advertising spending by companies in measured media for selected categories of products was used to approximate the amount spent by the food, beverage, and restaurant industries in 2004. An estimated $6.84 billion was spent on advertising in the food, beverage, and candy category and $4.42 billion was spent on advertising for restaurants and fast food, for a total of $11.26 billion. An additional $10.89 billion was spent on advertising for toys and games; sporting goods; media; and sedentary entertainment, including movies, DVDs, and music (Brown et al., 2005). Company data on how marketing budgets are allocated are often proprietary, however, and are thus not available to the public. Therefore, industry data that can be used to assess recent investments in healthful products are not widely available. As discussed later in the chapter, despite the high level of product innovation toward healthier choices that has been forecasted by industry analysts, most companies do not provide publicly accessible information on the investments that they make in research and development on healthier products (Lang et al., 2006). Furthermore, there is currently limited evidence that companies with product portfolios comprised largely of less healthful products are merging with or acquiring companies with healthier products (Insight Investment, 2006).

Branding is a goal of most companies and involves providing a name or symbol that legally identifies a company, a specific product, or a product line and that distinguishes it from other companies or similar products in the marketplace (Roberts, 2004). Branding has become a normalized part of life for American children and adolescents (Schor, 2004). The rate of brand loyalty is highest among adolescents, especially for carbonated soft drinks and QSRs. Brand loyalty may be related to the increased trend over the past 20–30 years in sweetened beverage consumption and the proportion of calories that children and youth receive from away-from-home foods, beverages, and meals, especially those purchased and consumed at full serve restaurants and QSRs. These products often contain higher amounts of fat and total calories than those products consumed at home (IOM, 2006).

After reviewing the available literature on branding and young consumers, the IOM Committee on Food Marketing to Children and Youth concluded that children are aware of particular food brands when they are as young as 2 to 3 years of age and that preschoolers demonstrate the ability to recognize particular brands when they are cued by spokes-characters and colorful packages. The committee also found that a majority of children’s food requests are for branded products.

Although the use of child-oriented licensed cartoon and other fictional or real-life spokescharacters to promote the consumption of low-nutrient and high-calorie food and beverage products has been a prevalent practice over the past several decades, the use of licensed characters to promote foods and beverages that contribute to healthful diets, particularly for preschoolers, is relatively recent (IOM, 2006). Preliminary evaluation and research results from the Sesame Workshop suggests that preschoolers may view fruits, vegetables, and other foods that contribute to a healthful diet more favorably if they are endorsed by familiar and appealing spokes-characters or mascots (Appendix H).

More recently, businesses, institutions, and communities are using branding to promote behavioral changes, often called lifestyle branding or behavioral branding. Such branding encourages individuals to associate a brand or a product line with a specific behavior, lifestyle, or social cause (Holt, 2004; IOM, 2006; Roberts, 2004; Tillotson, 2006a). Examples of initiatives that promote this type of branding are Active Living by Design (RWJF, 2006), Balanced Active Lifestyles (McDonald’s Corporation, 2006), Healthy Eating, Active Living (Kaiser Permanente, 2006), Health is Power! (PepsiCo, 2006a), Fruits and Veggies—More Matters!™ (PBH, 2006), the VERB™ campaign (Wong et al., 2004) (Chapter 4), and the American Legacy Foundation’s truth® campaign (Evans et al., 2005).

Given the growing concerns linking corporate marketing practices and the obesity epidemic among children, youth, and adults in the United States

(Dorfman et al., 2005; Freudenberg, 2005; Kreuter, 2005) and internationally (Lang et al., 2006; WHO, 2003, 2004; Yach et al., 2005), industry and individual companies should be involved in changing how they conduct business to address social and economic pressures and consumer demands. This is what marketers refer to as the “strategic inflection point” (Parks, 2002).

The Health in the Balance report emphasized that market forces may be influential in changing both consumer and industry behaviors. To lead healthier and more active lifestyles, young consumers and their parents will need to make positive changes in their own lives, including developing preferences for and selecting foods and beverages that contribute to healthful diets and regularly engaging in more active pursuits. All industries—the food, beverage, restaurant, recreation, entertainment, and leisure industries—should share responsibility for supporting consumer changes and childhood obesity prevention goals. These industries can be instrumental in changing social norms throughout the nation and internationally so that obesity will be acknowledged as an important and preventable health outcome and healthful eating and regular physical activity will be the accepted and encouraged standard (IOM, 2005). The childhood obesity epidemic needs to reach a “tipping point” (Gladwell, 2000), which is the point at which the collective changes made by industry, in concert with efforts in other sectors and by other stakeholders, will produce a large effect to make healthy behaviors and lifestyles the social norm.

It is important to recognize that corporations as employers have an interest in a healthy workforce with healthy families, and many employers are placing an increasing emphasis on obesity prevention and improved employee well-being. Corporate responsibility, health care costs, and lost productivity are key drivers in the development and promotion of employee wellness opportunities. Such employee benefits may include the provision of discounts for health club memberships or gyms at the workplace; offering foods and beverages that contribute to healthful diets in cafeterias, vending machines, and at meetings; and the promotion of walking breaks or physical activity during the work day.

Although this chapter primarily focuses on corporations as the producers and the deliverers of goods and services, corporations are also major consumers of health care and have an increasing interest in the outcomes and impact of obesity on their current and future workforces and their families.

EXAMPLES OF PROGRESS

Building consumer demand for regular physical activity and for foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet is an ongoing process that

is moving forward through the efforts of corporations that are willing to make changes to engage consumers in achieving healthy lifestyles. This will require the broad involvement of many sectors and stakeholders, including food, beverage, and restaurant companies; food retailers; trade associations; the leisure, recreation, and fitness industries; the entertainment industry; and the media (IOM, 2005, 2006).

Wansink and Huckabee (2005) have proposed three phases for the food and restaurant industries’ and trade associations’ response to the obesity epidemic. The first phase is to deny that they have a contributing role in the obesity epidemic by associating increasing obesity rates with the rising levels of physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles. The second phase is to appeal to consumer sovereignty by emphasizing moderation and consumer choice in their food and beverage intake, promoting physical activity, and asserting the rights of customers to decide on the appropriate selections for their own or their families’ lifestyles. The third phase is to develop win-win strategies that are profitable and that therefore satisfy company shareholder needs while concurrently meeting consumers’ needs for healthful products, portion control, and other steps that can lead them toward healthy lifestyles. Wansink and Huckabee (2005) have suggested several different types of changes that food, beverage, and restaurant companies can consider making and pilot testing to offer products that are both healthful to consumers and profitable (Table 5-1).

Several groups have offered suggestions and guidelines to the food industry and restaurant sector to help them provide healthier food, beverage, and meal options. The American Heart Association’s 2006 Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations provide several tailored recommendations specifically for these industry sectors (Lichtenstein et al., 2006; Box 5-4). The Keystone Forum on Away-From-Home Foods, supported by the FDA, also provides detailed recommendations on how consumers can make more healthful choices and what restaurants and food retailers can do to cater to consumer choices (Keystone Center, 2006). The following sections highlight some examples of changes that are in progress, many of which need to be evaluated. The committee highlights promising practices and raises issues relevant to increasing corporate involvement in this issue.

Product and Meal Development and Reformulation

Many industry leaders are testing a variety of new product development strategies, such as incorporating more nutritious ingredients into products (e.g., whole grains) and expanding healthier meal options at full serve restaurants and QSRs (e.g., fruit, salads, and low-fat yogurt). Making small changes to existing products to improve their healthfulness and continuing

TABLE 5-1 Influences on Consumption to Promote Healthier Diets

|

Consumption Driver |

Implications for Marketers |

|

Convenience Increase convenience by modifying the package and portion size. |

|

|

Cost Change the product but not the price. |

|

|

Taste Change the recipe but retain good taste. |

|

|

Knowledge Provide understandable labels and nutrition information but be realistic. |

|

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Wansink and Huckabee (2005). Copyright ©2005 by the Regents of the University of California. Reprints from the California Management Review, Vol. 47, No. 4. By permission of The Regents. |

|

to change these products over time by making incremental and systematic changes may help consumers develop preferences for more healthful choices.

There is evidence, however, of a greater segmentation of demand both within and between consumers. Thus, the health trend is not uniform across the entire population. Many consumers seeking healthful diets will exchange certain foods for healthier choices; at the same time, however, they may seek indulgent and high-calorie treats (IRI, 2006) that may offset the

|

BOX 5-4 Suggestions for Restaurants and the Food Industry to Adopt the AHA 2006 Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations Restaurants

Food Industry

SOURCE: Adapted with permission from Lichtenstein et al. (2006). |

benefits of the healthier choices. The restaurant industry reports that two out of three consumers surveyed indicate that their favorite restaurant foods provide flavor and taste sensations that they cannot easily replicate at home (Cohn, 2006; NRA, 2006). Additionally, more consumer segments seek different types of benefits from products (e.g., their purchases are for natural, organic, low-fat, low-calorie, or calorie-free products) (Sloan, 2006; Tillotson, 2006b).

New product development, product reformulation, and packaging are all important components of the marketing process. Companies are continuously developing new products or meal options or reformulating existing products and brands to keep pace with changing consumer preferences, technological developments, and the activities of their competitors. In 2000, a typical large supermarket offered approximately 40,000 products from more than 16,000 food manufacturers (Harris, 2002). Many of these products were developed for children and youth, as reflected by the annual sales

of food and beverages to children and youth, which were more than $27 billion in 2002 (Packaged Facts, 2003).

An analysis conducted by the IOM Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth assessed the trends in introduction of new products targeted to children and youth. The analysis used ProductScan®, an online global database that has tracked new consumer products and packaged goods introductions into the U.S. marketplace since 1980 (Marketing Intelligence Service, 2005), and examined 50 product categories and 16 beverage categories contained in the ProductScan® database (IOM, 2006; Williams, 2005). The analysis showed that for both food and beverage products, the overall trend lines increased upward from 1994 to 2004, indicating that the growth rate of introduction of both new food and new beverage products targeted to children and youth was greater than the growth rate for food and beverage products targeted to the general market. Overall, from 1994 to 2004, products high in total calories, sugar, or fat and low in nutrients dominated among the new foods and beverages targeted to children and youth (IOM, 2006). A decline in the numbers of both food and beverage products targeted to children and youth relative to those targeted to the general market occurred between 2003 and 2004. The decline may be attributed to recent scrutiny directed to the introduction of new products targeted to children and youth. It is uncertain whether the recent decline in new products targeted to children and youth is attributed to an overall decrease in the numbers of all new products introduced or whether it represents a selective reduction in the introduction of products in certain categories, such as those products deemed to be less healthful for children and youth (Williams, 2005).

Industry analysts recognize that there are many new product growth opportunities in the child- and youth-specific food and beverage market, especially for the categories of fresh produce, ready-to-eat meals, sauces and condiments, and fortified products (Business Insights, 2006; Sloan, 2006). Companies have begun to explore the development of new convenience foods and beverages (Blake, 2006; JPMorgan, 2006). The products that contribute to healthful diets of children and youth have been projected to be among the most active and profitable new product categories for industry from 2005 to 2009 (Business Insights, 2005). A recent industry analysis report suggests that 18 of the 24 fastest growing food categories globally are perceived to be healthier by consumers (Insight Investment, 2006).

There has also been a trend toward a decline in sales of high-calorie beverages and snacks. Analyses conducted for the beverage industry suggest that there has been a recent decrease in the volume of sales in the carbonated soft drink category (Beverage Digest, 2006). Morgan Stanley’s consumer marketing research forecasts that there will be an annual 1.5 percent

decline in carbonated soft drink sales volume in the United States over the next 5 years. The reasons for the projected decline are attributed to an increased concern about health and rising obesity rates that are influencing parents to monitor their own and their children’s carbonated soft drink intake (Wilbert, 2006). Marketing research also suggests that in 2005 the sales of high-calorie packaged snack foods, such as cookies and bakery items, decreased, whereas the sales of more nutrient-dense snacks, such as yogurt and food bars, increased (Packaged Facts, 2006). It is important to track these trends because the prevalence of snacking and the number of snacking occasions by children and youth have increased steadily over the past 25 years (IOM, 2006).

As emphasized in the Health in the Balance report, high energy-dense foods, such as potato chips and sweets, tend to be palatable but may not be satiating for consumers, calorie for calorie, thereby encouraging greater food consumption (IOM, 2005). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 encourages Americans to consume adequate nutrients within their calorie needs. More specifically, the Dietary Guidelines recommend that individuals consume a variety of nutrient-dense foods and beverages within and among the basic food groups while selecting foods and beverages that limit their intake of saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol. There is presently no consensus or guidelines that define a healthful food or beverage. However, an analysis of cross-sectional, nationally representative dietary intake data have found that low energy-dense diets, which include a relatively large proportion of foods high in micronutrients and water and low in fat, such as fruits and vegetables, are associated with better dietary quality and lower total calorie intake when compared to high energy-dense diets (Ledikwe et al., 2006). Longitudinal data are needed to support this relationship.

Both diversity and quality are important components of children’s and adolescents’ intakes, and energy balance may be more difficult to achieve when diets are high in total calories and fat (Kennedy, 2004). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 introduced the concept of “discretionary calories,” which represents the amount of calories that remain in a person’s energy allowance after he or she has consumed sufficient nutrient-dense foods to meet his or her nutrient requirements each day. An individual’s energy allowance is the amount of calories needed for weight maintenance. Discretionary calories are usually between 100 and 300 calories/day and depend on a person’s physical activity level (DHHS and USDA, 2005). A major challenge for food manufacturers has been to develop low energy-dense but palatable food and beverage products that help consumers to achieve dietary diversity and diet quality and to use their discretionary calories wisely to achieve energy balance at a healthy weight.

The committee recognizes that among food and beverage manufactur-

ers and the restaurant sector, there are examples of those who have undertaken important changes that collectively can contribute to reversing the epidemic of childhood obesity. As discussed later in the chapter, it is important to identify specific criteria, key performance indicators, and outcome measures that the public health sector and industry can mutually agree upon, and to use that information to make evidence-based changes to improve the public’s health. Specific criteria upon which positive industry changes can be evaluated may include: changes in a company’s product portfolio and marketing resources to develop, package, and promote products that contribute to healthy lifestyles; reducing the portion sizes of food and beverage products; designing initiatives that easily convey information to consumers about food, beverage, and meal products that meet established nutrition criteria; the provision of information that promotes regular physical activity; and developing partnerships with government and nonprofit organizations to increase the number and quality of programs that promote healthful eating and active lifestyles for children, youth, and their families.

Product Reformulation and New Product Innovations

Subsequent to the release of the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), many companies have made efforts to implement the recommendations pertaining to the development of product and packaging innovations that consider energy density, nutrient density, and standard serving sizes to help consumers make healthful choices. The committee also acknowledges that making a substantial change in their product portfolios toward healthier options is an evolving process that will require sufficient time and resources to conduct marketing research and market testing to determine the level of consumer demand and support for these products over the long term.

The Grocery Manufacturers Association’s (GMA) Health and Wellness Survey was conducted in 2004 and 2005 with 43 GMA member companies with total sales representing about half of the U.S. food and beverage industry sales. Forty-two of the companies reported introducing 4,496 new or reformulated products into the marketplace since 2002. These products were intended to improve consumer health. Based on information from 38 companies, 67 percent of the new or reformulated products had less saturated fat or trans fat content, 21 percent of these products had reduced calorie content, 20 percent of these products had reduced added sugar and carbohydrate contents, 12 percent of these products had increased vitamin or mineral content, and 8 percent of these products had reduced sodium content (Kretser, 2006).

Although it is still too early to comprehensively evaluate the rate and

extent of healthy new product innovations across the food and beverage industry, there are encouraging signs, with leading food and beverage companies (e.g., General Mills, PepsiCo/Quaker Oats, and Kraft Foods) responding with product innovations targeting healthier nutrition profiles. Many of these products are designed to help consumers meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 and offer other benefits, such as increasing whole-grain consumption, encouraging low-fat dairy consumption, and reducing calorie consumption to help consumers balance their calorie intake with their energy expenditure (GMA, 2006). Increases in promotional spending by the larger produce brands (e.g., Dole, Chiquita, and Sunkist) are also apparent, and there has been a leveraging of both private-sector resources (e.g., public service announcements produced through in-kind media, food retailer, and other producer support or commodity board inkind support) and public-sector resources (e.g., USDA and National 5 a Day partner support) to create an awareness among consumers about the need to increase fruit and vegetable intake through a multisectoral national action plan (PBH, 2005a,c). Many of their activities are targeted to children and youth.

In an effort to overcome the taste barrier, which consumers often provide as a reason for their lower than recommended levels of vegetable consumption, companies such as General Mills’ Green Giant brand are packaging frozen vegetables with sauces that complement the vegetables and make their taste more desirable (General Mills, 2006a). As the parent company for Cascadian Farm®, General Mills is expanding efforts to provide organic fruits and vegetables to the mainstream marketplace by meeting the demand of a growing segment of consumers for organic and natural foods (General Mills, 2006a).

The senior-level management of PepsiCo has committed to the goal of having 50 percent of its revenues from new products come from its healthful branded product category. According to the company representative who made a presentation at the IOM symposium on industry, the rate of sales of these products is growing at approximately three times the rate for the rest of the company’s product portfolio. Kraft Foods has set similar goals for its business and is also seeing strong growth in demand for its healthier products in the marketplace. This demand may serve to drive competition further and may result in innovation within companies to reformulate existing products or to develop new products such that they can be tagged with the healthy icon or logo. The increased demand may also reaffirm the commitments by corporations to supply healthful products in the marketplace (Appendix H).

These examples highlight the type of leadership required to stimulate broader change within the food, beverage, and restaurant industries. If the largest global companies make these types of commitments and implement

them, smaller companies are more likely to follow. It may also influence the house brands or “value” brands of leading food retailers so that they emulate the changes made to the brands of the more recognized companies. This process could lead to a chain of events that has the potential to substantially shift the product portfolios of food, beverage, and restaurant companies and influence how companies, food retailers, and trade associations conduct business. However, these changes need to be evaluated to assess the extent of the changes that companies have made, the impact of these changes on consumers’ response and dietary behaviors, as well as business impact.

Food Retailers

The food retailer is an important stakeholder in childhood obesity prevention because it serves as the interface between manufacturers and consumers. Industry stakeholders and public health practitioners often overlook this untapped setting as a means of reaching young consumers with healthful products and health-promotion initiatives. Supermarkets, grocery stores, and other food retail outlets are venues for product selection, merchandising and product promotion, and consumer education. Opportunities exist to make the products selected in these settings more healthy. Such opportunities include identifying for children branded products that have healthier profiles; developing healthier private-label products for young consumers as well as the entire family; introducing portion-controlled, packaged foods and beverages; and increasing the convenience of purchasing fresh fruits and vegetables. A variety of in-store merchandising and promotion activities can bring healthier choices to the attention of consumers. These include shelf markers, package icons or logos, and special displays that can be used to flag healthier products for children, youth, and family meals. Cross-merchandising, premiums, product sampling, in-store promotional entertainment, and price promotions can also be used to highlight healthier options (Childs, 2006).

Expanding Consumer Demand for Healthful Products

A substantial barrier to this progressive shift in the food, beverage, and meal product landscape is the continuous need to build consumer demand for healthful products. The new products must have an appealing taste, look appealing, be convenient, and represent value to consumers compared with those of the products that they will replace. Although health is an important driver of the food industry, consumers are less willing to trade taste for health (Sloan, 2006). Taste is consistently identified as a key driver of consumption, followed by price, convenience, ease of preparation, and

freshness (Yankelovich, 2006). This process will require continued investment in improved technologies that can make healthier foods and beverages taste better, that can improve convenience (e.g., longer shelf life and reduced preparation time) and that can offer high value (e.g., low cost products with innovative packaging). This investment can emerge from consumer demand and the success of early versions of these products in the marketplace.

Many full serve restaurants and QSRs are expanding the availability of healthier items on their menus; establishing their own guidelines for advertising and marketing of food, beverages, and meals; and educating their customers by providing nutrition information and product labeling. For example, Burger King provides a nutrition guide online; Denny’s has the D-Zone Kids’ Menu; Pizza Hut has the Fit ‘N Delicious menu; and Chick-fil-A advertises The Trim Trio™, a combination meal with 330 calories, less than 4 grams of fat, and no trans fat (Cohn, 2006).

These efforts are now beginning to get some recognition through innovative awards programs that are being established to highlight restaurants that offer healthier choices. Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee established an awards program for restaurants under his Healthy Arkansas initiative (2006). This program was developed to recognize restaurants that assist Arkansas residents to make healthy choices when they eat away from home. Three categories of awards (gold, silver, and bronze) are given to restaurants that meet specified standards established for food safety; provide healthier menu options, such as at least one fruit and vegetable without added sugar or fat, and nutrition information and education about the their meals; and have designated smoke-free areas. Restaurants may show Healthy Arkansas Restaurant logos to promote their receipt of the award. Currently, 138 restaurants across the state have applied for the designation as a Healthy Arkansas establishment. Among the QSRs that have received the designation are McDonald’s Corporation, Subway, and a variety of Yum! Brands chains including Burger King and Pizza Hut.

The restaurant sector’s previous attempts to change products and sell healthier menu items, such as McDonald’s Corporation’s McLean Deluxe burger and Taco Bell’s lower-fat Border Lights menu, launched in the 1990s, have received mixed results (Collins, 1995; Ramirez, 1991). The reasons for their low profitability are complex and not well documented. McLean Deluxe may have benefited from a more creative presentation and promotional effort while Border Lites may have had less appeal to their teenage customer base. The new menu introductions may have been too early for consumers to perceive them as necessary, as the obesity epidemic has only recently been raised to the level of broad public awareness.

Alternatively, these early attempts to sell healthier options may have been unprofitable because the main consumer benefit that was marketed

was health instead of taste or convenience. As Wansink and Huckabee (2005) suggest, most consumers generally equate healthful foods with compromised taste, especially since healthier choices are generally marketed as new and different, as well as healthier, which may raise consumer concern about how the new product will taste. If the product is more expensive than the alternative and often less healthy choice, it will not be appealing or affordable to a large segment of consumers.

Building and sustaining consumer demand for reformulated food and beverage products and restaurant meals is an important strategy for helping Americans to consume more healthful diets. Achieving this goal will require continued innovation around the composition and packaging of foods, beverages, and meals; improvements in the taste of healthier products; and making them convenient and affordable for consumers. Innovative approaches are needed to change consumers’ perceptions of the taste and desirability of healthier products. Similarly, it is important to highlight the changes in consumer expectations that are needed and the trend toward eating more of their meals outside of the home. As consumers’ incomes increase, they eat away from home more frequently and spend a greater proportion of their food dollar on meals consumed away from home (NRA, 2006). Making healthy choices at such meals also needs to be viewed as integral to healthful eating and not as a treat or a special occasion.

Product Packaging and Meal Presentation

Food and Beverage Companies

Package size, plate shape, restaurant ambiance, and lighting are environmental factors that can influence the volumes of food, beverages, and meals consumed. Small changes in these factors can be instrumental in reducing the overconsumption of foods (Wansink, 2004). According to the GMA Health and Wellness Survey, conducted with 42 GMA members, 50 percent had either changed or initiated a change in multiserving packaging, and 56 percent of 41 companies had created special package sizes for children and youth (GMA, 2006; Kretser, 2006). Specific packaging innovations have included changing single-serving milk from unresealable cartons to resealable plastic bottles that have up to a 3-month shelf-life; replacing aluminum cans that contain meals such as chili with shelf-stable, single-serving carton packaging or plastic cupped or bowled packages; and using portable and resealable pouches that can contain a variety of products including beverages, snacks, candy, cereals, meats, soups, and sauces (Fusaro, 2004).

In addition, other recent new packaging initiatives by Kraft Foods and PepsiCo have introduced 100-calorie packages of popular snack food brands.

The single-serving, calorie-controlled packages can potentially meet consumer demand for convenience, establish a new and acceptable portion size standard for consumers (Sloan, 2006), and assist consumers with limiting their consumption of snacks at a single eating occasion. However, evaluations of these initiatives are needed to demonstrate that consumers do not overcompensate by consuming more of the calorie-controlled packages or consuming more calorie-dense foods or beverages at other times of the day.

Restaurants

The Health in the Balance report recommended that full serve restaurants and QSRs expand their healthier food options and provide families with the calorie content and general nutrition information of their meals at the point of purchase (IOM, 2005). The restaurant industry estimates that the full serve restaurant and QSR sector will have provided approximately 70 billion meals or snacks to U.S. consumers in 2006 (NRA, 2006). More than 925,000 commercial restaurants are projected to generate an estimated $511 billion in annual sales in 2006, an increase from $42.8 billion in 1970. The restaurant industry’s share of American’s food dollar is approximately 47.5 percent (NRA, 2006) and is projected to increase to 53 percent by 2010 (Cohn, 2006).

In this report, the term fast food is used to describe the foods, beverages, and meals designed for ready availability, use, or consumption and that are sold at eating establishments for quick availability or takeout (Appendix B). This definition is similar to that provided by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), which defines fast food restaurants as the U.S. industry sector that “comprises establishments primarily engaged in providing food services where patrons generally order or select items and pay for them before eating. Food and drink may be consumed on the premises, taken out, or delivered to the customer’s location” (NAICS, 2002).

It has been suggested that researchers have no universally accepted definition of fast food, which may present methodological challenges for accurately describing the characteristics of the foods, beverages, and meals obtained at these establishments (Kapica et al., 2006). However, a robust evidence base from over the past 25 years is available and documents that a large proportion of foods, beverages, and meals purchased from fast food restaurants or QSRs tend to have larger portion sizes and are higher in total calories (from fat and added sugars) and energy density than foods, beverages, and meals prepared and consumed at home (IOM, 2005, 2006).

The percent of total calorie intake of children and adolescents ages 12 to 18 years obtained from foods purchased and consumed away from home increased from 26 to 40 percent between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996

(Nielsen et al., 2002b). Trends in the calorie intakes of children and adolescents ages 2–18 years by selected eating locations showed a substantial increase in away-from-home calories obtained from restaurants, especially QSRs, from 5 percent in 1977–1978 to 15 percent in 1994–1996 (Nielsen et al., 2002a). Data for more recent trends in young peoples’ calorie intake from foods and beverages obtained at restaurants are not available. A review of the available literature finds that nearly one-half of away-from-home calories obtained at full serve restaurants and QSRs were higher in fat content (IOM, 2006). Although healthier menu options are gaining attention, most QSRs continue to offer choices that are predominantly high in total calories, saturated fat, sugar, and salt. Many QSRs indicate that sustained consumer demand is inextricably related to a broader sustained societal effort focused on promoting healthier choices (IOM, 2006).

Restaurants are important venues for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. A recent survey, combined with menu trend research, found that although 67 percent of consumers reported visiting a QSR at least once every 2 weeks, only 18 percent reported regularly consuming fruits or vegetables from such restaurants. Additionally, whereas 13 percent of all meals are eaten at or carried out from a commercial restaurant (including casual dining and QSRs), only 7 percent of total fruit and vegetable servings were consumed at restaurants. Many opportunities exist to use plate presentation, promote convenience, and use limited-time offers and incentives to promote produce consumption when consumers eat out at restaurants (PBH, 2005b).

The growing public concern about obesity presents certain marketing risks—such as increased costs associated with developing, reformulating, packaging, test marketing, and promoting food and beverage products, as well as uncertainty related to creating and sustaining consumer demand for these new products. However, the public’s interest and concern also present potentially profitable marketing opportunities not yet fully explored: food and beverage manufacturers can compete for and expand their market share for healthier food and beverage product categories, serve as role models for the industry by substantially shifting overall product portfolios toward healthier products, and engage in socially responsible corporate behaviors in the response to the childhood obesity epidemic. Despite the challenges of market forces and the marketplace, companies can make positive changes that expand consumers’ selection of healthier products, as well as to reduce the risks of government regulation or litigation (Mello et al., 2006).

Physical Activity Opportunities

The Health in the Balance report recommended that the leisure, entertainment, and recreation industries develop products and opportunities

. that promote regular physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviors (IOM, 2005). Although some efforts are under way to develop products that enhance opportunities for physical activity, additional investment in both the development and the promotion of products that support increased physical activity levels is needed.

Using home videogame systems is a sedentary activity that has been associated with a higher body mass index (BMI) level in children who spend more time engaging in such activities (Stettler et al., 2004; Vandewater et al., 2005). Recently, the videogame industry has used its creativity to increase children’s awareness about obesity. The annual Games for Health (2006), a conference produced by The Serious Games Initiative, convenes game manufacturers to focus on health-related issues. Such products as a fantastic voyage-style adventure called Escape from Obeez City have been developed in which children explore the impact of obesity on the human body (Big Red Frog, 2006; Brown, 2006). Another example is the videogame Squire’s Quest!, which is designed to allow children to earn their way to knighthood through such tasks as creating fruit- and vegetable-containing recipes. Two separate evaluations of this videogame found that children playing the game increased their fruit and vegetable consumption by one serving compared with the levels of fruit and vegetable consumption of children who did not play the game (Baranowski et al., 2003; Cullen et al., 2005).

Interactive videogames, also called physical gaming, are electronic games that use the players’ physical activity as input in playing the game. The media has paid special attention to physical games such as Dance Dance Revolution®, in which players use a floor pad to mimic dance moves shown on a screen. The most recent version of this videogame informs players about how many calories they burn in each dance session (Brown, 2006). Interactive videogames for the PlayStation2® computer entertainment system use the EyeToy™, a tiny camera that projects an image of th game player directly onto the screen. These methods of physical gaming, however, often require the purchase of an additional piece of equipment, such as a dance pad or a camera, which adds to the cost of the system, thereby limiting the potential audience. Nevertheless, innovative approaches to physical gaming are being developed and offer promising possibilities.

Some companies are beginning to produce branded physical activity equipment for children and youth. For example, McDonald’s Corporation has started a new multicategory licensing initiative called McKIDS™ that unifies its branded product line including toys, interactive videos, books, and DVDs to reflect active lifestyles (McDonald’s Corporation, 2003). The McKIDS™ line of products offers branded bikes, scooters, skateboards, outdoor play equipment, and interactive DVDs. There is a need for evaluations that assess how these products are promoted to children and youth

and whether use of the branded equipment promotes desirable behavioral and health outcomes.

Advertising and Marketing Communications

The media and entertainment industries have a tremendous reach into the lives of the American public. These industries have important opportunities and responsibilities to depict and promote healthful diets and physical activity among children and youth (IOM, 2006). Among the many challenges in addressing the reach and the influence of paid media and marketing communications in the lives of children and youth are the multiple venues and vehicles that can be used to deliver consistent messages that promote healthy lifestyles (IOM, 2006).

Advertising and Marketing Strategies, Venues, and Vehicles

Today’s paid media and marketing strategies, tactics, and messaging extend beyond traditional print and broadcast or cable television advertising, which is relatively easy to monitor and control, to newer forms of interactive media and marketing communications such as product placement across multiple media platforms, Internet marketing, and mobile or wireless telephone marketing. Two recent studies that examined Internet marketing designed by food and beverage companies for children and youth documented a range of techniques used to engage and immerse children in company brands. These techniques include advergames, brand identifiers, brand characters, brand benefit claims, customized Internet visits, viral marketing, cross-promotional paid media tie-ins, and on-demand access to television advertisements (Moore, 2006; Weber et al., 2006).

Companies advertise and market to children and youth through a variety of venues and use many strategies to develop brand awareness and brand loyalty at an early age. One company that made a presentation at the industry symposium, Kraft Foods, announced in 2005 that it would advertise to children ages 6 to 11 years only those food and beverage products meeting the company’s healthful criteria, during children’s broadcast television, radio programming, and in paid print media geared toward this age group. The company indicated that by the end of 2006, it will redesign its websites intended for viewing by children ages 6 to 11 years so that they feature only products that meet the Sensible Solution™ nutrition standards of their more healthful product line (Gorecki, 2006; Kraft Foods, 2005). However, these proposed guidelines will not apply to products promoted on television during prime-time programs viewed primarily by adults or coviewed by children and youth with their parents.

In accordance with this marketing trend, the entertainment media, particularly television programs and broadcast and cable television networks targeting children and youth, have begun to promote fruit and vegetable consumption and other healthful behaviors. They have also entered into partnerships that feature product cross-promotions, which market new products or products related to those already used by consumers. Certain media outlets use approaches that are based on the finding that children often view food as having physical characteristics as well as social constructs. Sesame Workshop, in partnership with the Produce for Better Health Foundation (PBH), uses its characters to model fun ways to move and play as well as ways to encourage snacks that support a healthful diet (PBH, 2005a). Additionally, PBH is also partnering with Wal-Mart, the nation’s largest retailer, to conduct a series of in-store marketing activities using Shrek, Charlie Brown, Spiderman®, Curious George®, and Peter Rabbit™ to promote fruit and vegetable consumption (Childs, 2006; PBH, 2005a). Evaluations of the partnerships, policies, and outcomes related to these interventions are needed.

The Cartoon Network has initiated a healthy lifestyles program called Get Animated that uses celebrity endorsements and partnerships to extend its outreach to children and families to encourage physical activity and making choices that contribute to a healthful diet. In conjunction with its cable television campaign, the network sponsors a nationwide tour of cartoon-based spokescharacters that involve children in various activities to show that fruits, vegetables, and physical activity can be fun and cool (Time Warner, 2006) (Appendix H).

Univision Communications is the leading Spanish-language media company in the United States. (The company’s television operations include the Univision Network, TeleFutura Network, Galavisión, and the Univision and TeleFutura Television Groups. Univision also owns and operates Univision Radio, Univision Music Group, and Univision Online.) The company’s multimedia obesity-related initiatives focus on promoting healthy lifestyles by educating and engaging the Hispanic and Latino communities and engaging individuals in these communities in ways to be healthy. By collaborating with health care organizations, community groups, and allied health professional societies and organizations, the network created several public service announcements, special programs, commercials, and news segments that it regularly features to promote health and nutrition among its primarily Spanish-speaking viewers (Univision Communications, 2003). It also partners with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative We Can! to inform parents about ways to help them encourage their children to maintain a healthy weight (NHLBI, 2006) (Appendix D).

Some efforts are underway to use storylines and programming that promote healthy lifestyles. Media messages regarding healthy lifestyles are

facilitated by organizations such as Hollywood, Health, and Society, an organization based at the University of Southern California that focuses on linking television writers with health experts so that accurate health and nutrition information can be integrated into their television program scripts. This program was formed with support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the NIH. The organization facilitated the incorporation of a storyline about diabetes into a popular television show on a major Hispanic network. An evaluation of the impact of this effort included tracking of the numbers of individuals who accessed diabetes information that was linked through the network’s website and promoted on the television show (Appendix H).

In 2004, the Ad Council, a private nonprofit organization that provides public service advertising, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), formed a public-private partnership, the Coalition for Healthy Children, to formulate research-based messages targeted to parents, children, and youth through the collective strength of the food, beverage, restaurant, and marketing industries; the media; nonprofit organizations; foundations; and government agencies. The coalition members work to provide consistent messages about physical activity, food choices, portion sizes, the balancing of food and physical activity, and parental role modeling across multiple media platforms. They also work to incorporate consistent messages into their internal communications programs as well as their advertising, packaging, websites, community-based programs, and marketing events (Ad Council, 2006b). In 2005, an evaluation of the coalition activities concluded that although consumer awareness is relatively high for healthy messages about diet and activities, the attitudes and behaviors of children and parents do not reflect this heightened awareness (Yankelovich, 2005). An evaluation is under way to assess how the effectiveness of the Ad Council’s obesity prevention messages compare with the effectiveness of other advertising and marketing messages of food and beverage companies within the advertising information environment (Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2005).

Spokescharacters are a particularly important marketing strategy used to reach young children. In 1963, the McDonald’s Corporation created Ronald McDonald as a spokescharacter who appealed to children, with the purpose of promoting the foods, beverages, and meals served and consumed at the QSR franchise (Enrico, 1999). In 2005, Ronald McDonald became the company’s spokesperson to advocate “balanced active lifestyles” (McDonald’s Corporation, 2005). His image was changed to emphasize physical activity and to introduce and promote some healthier options. Although a relatively recent development, publicly available information about the outcomes and impact of this change on children’s diets and physical activity behaviors would be useful.

In 2005, Nickelodeon—a company of Viacom International, which is a leading entertainment company for American children—announced that it would begin licensing several of its popular cartoon spokescharacters, including SpongeBob SquarePants® and Dora the Explorer®, to produce companies to promote fruit and vegetable consumption (Smalls, 2005). In 2006, Nickelodeon announced plans to license the use of images of these characters to promote the consumption of apples, pears, cherries, and soybeans (Horovitz, 2006). Other characters are being used to promote fruit consumption, including the Warner Brothers characters Bugs Bunny™ and Tweety™ Bird and the Sesame Workshop’s characters Elmo™ and Cookie Monster™ (Horovitz, 2006; Sunkist, 2005). Independent evaluations that assess these characters’ appeal and influence on children’s food preferences, product sales, and the levels of consumption of fruits and vegetables are needed.

Self-Regulatory Guidelines: Children’s Advertising Review Unit

The industry-supported, self-regulatory Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU) was formed in 1974 as an industry self-regulatory mechanism to promote responsible advertising and promotional messages for children and youth under 12 years of age. The purpose of industry self-regulation is to ensure that advertising messages directed to young children are truthful, accurate, and sensitive to this audience (CARU, 2003a,b). CARU works with food, beverage, restaurant, toy, and entertainment companies, as well as advertising and marketing agencies, to ensure that advertising messages directed at children younger than 12 years adhere to these guidelines (CARU, 2003a,b) (Box 5-5).

An assessment conducted by the National Advertising Review Council (NARC, 2004), which establishes policies and procedures for CARU, suggests that within its designated technical purview, the CARU guidelines have generally been effective in enforcing voluntary industrywide standards for traditional forms of advertising and that the number of advertisements that contain words and images that directly encourage children to consume excessive amounts of food has been reduced (IOM, 2006). Nevertheless, CARU reviews advertisements for accuracy and to reduce deceptive advertising, but it does not have the ability to monitor or regulate the nutrition information provided by commercials. Implicit in the NARC review findings is the limited scope of authority of CARU. The guidelines do not address issues related to the volume of food, beverage, and meal advertising targeted to children and youth; the broader marketing environment; or the many integrated marketing strategies that have increased to reach young people since CARU’s inception in 1974 (IOM, 2006).

|

BOX 5-5 Groups Relevant to Advertising and Marketing Practices Affecting Children and Youth National Advertising Review Council The National Advertising Review Council (NARC) was established to provide guidance and develop standards for truth and accuracy in national advertising through a voluntary self-regulation system. NARC sets the policies for the National Advertising Division, National Advertising Review Board, Children’s Advertising Review Unit, and the Electronic Retailing Self-Regulation Program. Children’s Advertising Review Unit The Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU) promotes responsible children’s advertising as part of a strategic alliance with the major advertising trade associations through NARC, including the American Association of Advertising Agencies, the American Advertising Federation, the Association of National Advertisers, and the Council of Better Business Bureaus. CARU is the children’s arm of the advertising industry’s self-regulation program and evaluates child-directed advertising and promotional material in all media to advance truthfulness, accuracy, and consistency with its Self-Regulatory Guidelines for Children’s Advertising and relevant laws. American Association of Advertising Agencies The American Association of Advertising Agencies (AAAA) is the national trade association representing the advertising agency business in the United States. Its membership produces approximately 80 percent of the total advertising volume placed by agencies nationwide. It provides to its members guidance on strengthening their advertising practices. American Advertising Federation The American Advertising Federation (AAF) is an industry trade association that works to protect and promote advertising practices through a nationally coordinated grassroots network of members that include advertisers, advertising agencies, media companies, local advertising clubs, and college chapters. |

Consumer advocacy groups have expressed growing concern about CARU’s ability to effectively monitor children’s food and beverage advertising, given the newer forms of marketing across multiple forms of media (e.g., broadcast and cable television; and print, electronic, and wireless media) that are often difficult to monitor and regulate. In response to this concern, the industry trade association, GMA, proposed a seven-point plan to strengthen CARU’s enforcement capacity to effectively self-regulate the industry. These suggestions also provided guidance on enhancing CARU’s visibility, resources, transparency, and public accessibility (GMA, 2005).

At the IOM industry symposium in Irvine, California, the director of NARC announced that in response to these requests, CARU had appointed

|

Association of National Advertisers The Association of National Advertisers (ANA) provides leadership to drive marketing communications, media and brand management excellence, and to promote and defend industry interests. Council of Better Business Bureaus The Council of Better Business Bureaus (CBBB) is the parent organization for the Better Business Bureau (BBB) system, which is supported by more than 300,000 local business members nationwide, and works to foster fair relationships between businesses and consumers. The CBBB and all local Better Business Bureaus are private, nonprofit organizations funded by membership dues and other support. American Marketing Association The American Marketing Association (AMA) is a professional association for individuals and organizations involved in the practice, teaching, and study of marketing worldwide. It serves to advance marketing competencies, practice, and leadership; to advocate for marketing efficacy and ethics; and as a resource for marketing information, education, and training. Ad Council The Ad Council is a private, nonprofit organization that mobilizes volunteer talent from the advertising and communications industries, the facilities of the media, and the resources of the business and nonprofit communities to deliver messages to the American public. The Ad Council produces, distributes, and promotes thousands of public service advertising campaigns annually in such areas as improving the quality of life for children, preventive health care, education, community well-being, environmental preservation, and strengthening families. SOURCES: AAAA (2006); AAF (2006); Ad Council (2006a); AMA (2006); ANA (2006); CARU (2003a,b); CBBB (2005). |

a new director of communications, added two child nutritionists to its advisory group, and established three task forces to examine the need for expanding the group’s purview (e.g., websites and interactive media, paid product placement in children’s programming, and the appropriate use of licensed characters in food and beverage promotion). It was also reported that CARU has built a closer relationship with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to strengthen the voluntary industry self-regulatory approach (Appendix H), which is acknowledged and encouraged by these federal government agencies (FTC and DHHS, 2006). Support by these federal agencies is essential to assist the industry with defining advertising and marketing

guidelines appropriate for each sector (e.g., foods, beverages, restaurants, leisure, and entertainment). CARU also reported that companies appear to be incorporating the CARU guidelines into their own advertising review systems and request that CARU conduct prescreening of their advertisements (CBBB, 2006).

The Health in the Balance report recommended that industry develop and strictly adhere to marketing and advertising guidelines that minimize the risk of obesity in children and youth (IOM, 2005). To reach this goal, the IOM committee recommended that DHHS convene a national conference to develop new guidelines for the advertising and marketing of foods, beverages, and sedentary entertainment directed toward children and youth, with attention given to product placement, promotion, and content. The IOM committee also recommended that industry implement the advertising and marketing guidelines, and that FTC be given the authority and resources to monitor compliance with these practices and guidelines (IOM, 2005).

The IOM report Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? provides three additional recommendations related to advertising and marketing to children and youth (IOM, 2006). First, it recommends that industry work through CARU to revise, expand, apply, enforce, and evaluate explicit industry self-regulatory guidelines beyond traditional advertising to include evolving vehicles and venues for marketing communication (e.g., the Internet, advergames, and branded product placement across multiple media platforms). Second, the report recommends that industry ensure that licensed characters6 are used only for the promotion of foods and beverages that support healthful diets for children and youth. Third, it recommends that industry foster cooperation between CARU and FTC to evaluate and enforce the effectiveness of the expanded self-regulatory guidelines (IOM, 2006).

In July 2005, FTC and DHHS held a joint workshop, Marketing, Self-Regulation, and Childhood Obesity, that provided a forum for industry, academic, public health advocacy, and government stakeholders, as well as consumers, to examine the role of the private sector in addressing the rising childhood obesity rates. A summary of the workshop contains recommendations and next steps for industry stakeholders, including a request that industry strengthen self-regulatory measures to advertise responsibly to children through CARU. FTC and DHHS both indicated that these institu-

tions plan to closely monitor the progress made on the recommendations in the joint FTC and DHHS summary report (FTC and DHHS, 2006). Moreover, through Public Law 109-108, FTC has requested public comment and information on food industry marketing activities targeted to children and adolescents and expenditures for those activities. The public comments and information will be submitted in a report to Congress (FTC, 2006).

CBBB has recognized the need to consider changes in the self-regulatory advertising guidelines to respond appropriately to new marketing techniques and also to the knowledge about children’s cognitive abilities in understanding marketing messages (CBBB, 2006). Children younger than 7 to 8 years of age lack the cognitive skills to discern commercial from non-commercial content—that is, they are unable to attribute persuasive intent to advertising and other forms of marketing. Children usually develop these skills at about the age of 8 years; however, children as old as 11 years of age may not activate these cognitive defenses, especially with embedded forms of marketing, such as product placement in commercials and programs, unless they are explicitly cued to activate these skills (IOM, 2006).

In early 2006, CBBB announced plans to review the CARU guidelines for advertising to children. As part of the CARU review process, an industry working group that receives input from a diverse group of CARU advisers has been established. The industry working group is currently engaged in an ongoing process to consider whether and how the industry self-regulatory guidelines should be revised and has indicated that the scope of the review will be broad. After the review, the industry working group will make recommendations to the board of directors of NARC, CBBB, and the Electronic Retailing Self-Regulatory Program. Once the NARC board has given approval, the recommendations will be posted for public comment and the NARC board will consider implementing the recommendations (CBBB, 2006).

Information and Education

Information and education are necessary but not sufficient factors to promote behavioral changes in young consumers and their parents. The recommended items should be available, accessible, affordable, appealing, and sufficiently promoted to consumers. One of the approaches that has been adopted by food and beverage manufacturers to help consumers make healthier product choices is to highlight the existing products in their portfolios that meet certain nutrition standards that are based on recommendations by FDA, the IOM’s Dietary Reference Intakes, and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. Such nutrition standards include limits for the percentage of calories derived from fat, saturated fat, and trans fat; sugar, sodium, and

fiber content; the reduction of calories and fat compared with those of other brands; or food-based guidelines that support the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. One way to assist consumers in recognizing these products is to put a branded icon or logo on the front label of the product package to indicate that these items meet established nutrition criteria.

PepsiCo uses the SmartSpot™ logo to distinguish “good for you” and “better for you” products from their other portfolio products, and Kraft Foods uses the Sensible Solution™ logo to identify products whose nutrient contents meet specific nutrient criteria according to the guidelines of FDA and IOM. General Mills promotes 14 different Goodness Corner™ icons (e.g., “whole grain” symbol) that meet specific nutrient criteria according to FDA guidelines that define limits for calories, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, added sugars, and sodium; identify products that are high in fiber, vitamins, and minerals; and meet the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans food-based guidelines.

This type of product branding enables consumers to identify healthful products as determined and conveyed by the company that makes and promotes the products. The healthy logos or icons may serve to build brand awareness and brand loyalty among consumers by making it easier for them to identify healthier products. The icons have the potential to provide clear and positive messages, demonstrate the companies’ efforts toward expanding the healthier product portfolios, and providing healthful solutions to customers. Because the proprietary logos or icons that food companies have introduced to communicate the nutritional qualities of their branded products to consumers have not been evaluated, it is not yet known how consumers understand them. There may also be great variations in the consistency, accuracy, and effectiveness of these logos or icons (IOM, 2006). Furthermore, these icons may be useful for a company but do not broadly encourage the consumption of fruits and vegetables or allow comparison among brands (Appendix H).

As a means of addressing these concerns, in 2007, PBH—in partnership with the government and nonprofit organizations—plans to launch a new brand, The Fruits and Veggies—More Matters!™, and an icon that is intended to be easily recognized by consumers to promote the greater consumption of produce. The brand is designed to communicate the higher recommendations for produce put forward by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (PBH, 2006).

As noted at the IOM industry symposium, a standard industrywide logo or icon may be more useful to consumers. All corporations could then use such a standard to designate products that meet agreed-upon nutrition and health standards. The present IOM committee encourages the pilot testing and formative evaluation of the feasibility of implementing an industrywide logo and icons that promote fruit and vegetable consumption.