1

Introduction

In 2004, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the report, Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance, which provided a blueprint for a comprehensive action plan to prevent childhood obesity1 in the United States (IOM, 2005). The report emphasized an urgent need for collective responsibility and concerted actions to be undertaken by multiple stakeholders across different sectors—including the federal government, state and local governments, communities, schools, industry, media, and families—to address the evolving childhood obesity epidemic by preventing children and youth who are currently at a healthy weight2 from developing a body mass index (BMI) at or above the sex-specific 95th percentile that defines obesity. Even as that report was being prepared, many childhood obesity prevention programs and policies were being initiated or already underway around the nation.

In the two years since the release of the Health in the Balance report, childhood obesity prevention efforts have become the topic of discussion and the focus of action in homes, schools, communities, corporations, state legislatures, and federal agencies across the nation. Unfortunately, few of these new or ongoing efforts are being systematically documented or evaluated, thereby limiting the potential to learn from these efforts and to use the results in further developing and refining population-based approaches to prevent childhood obesity.

This subsequent IOM report, Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: How Do We Measure Up?, assesses progress made on the first report’s recommendations by focusing on the evaluation of actions taken by all sectors of society. Given the numerous changes being implemented throughout the nation to improve the dietary quality and extent of physical activity for children and youth, an overarching assessment of progress in preventing childhood obesity necessitates both the tracking of trends across the nation and a more detailed examination of lessons learned through the evaluations of relevant interventions, policies, and programs. Evaluation is the basis for identifying effective interventions that can then be scaled up to statewide or nationwide efforts as well as ineffective interventions that can be refined or replaced with efforts that are shown to be more promising as a result of evidence-based analyses. A complementary set of efforts is needed—population-based public health interventions coupled with individual-level and institutional interventions—and these efforts should be collectively monitored and evaluated. The childhood obesity epidemic is at the point where it is time to move beyond a reactive small-scale approach and toward a proactive, coordinated, and sustained response.

As the previous report acknowledged, there is an urgent need for action on this public health concern—action requiring the use of the best available evidence. Now that numerous changes are underway to increase physical activity and improve dietary intake it is time to bolster the evidence base. Key questions to consider include the following: Are interventions to promote a healthful diet and to increase physical activity reaching enough people to make a difference? Is the breadth of interventions sufficiently adequate to address the scope of the problem? Much remains to be learned about how to effectively increase physical activity, improve dietary quality, and decrease sedentary lifestyles in America’s children and youth.

HEALTH IN THE BALANCE REPORT

The Health in the Balance report acknowledged the many transformations in U.S. society over the past 30 years—including changes in the physical and built environments, social and cultural environments, and commercial and media environments—that have contributed to the energy

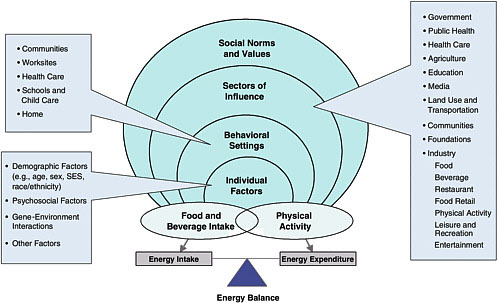

imbalance and rising prevalence of obesity among America’s children and youth. Using an ecological approach to identify leverage points for designing effective interventions to promote energy balance, the report addressed the range of factors that influence diet and physical activity: individual factors, behavioral settings, sectors of society, and the social norms and values that reinforce healthful eating and regular physical activity as the accepted and encouraged standard (Figure 1-1) (IOM, 2005).

The report concluded that childhood obesity is a nationwide health crisis requiring a population-based prevention approach and a substantial and comprehensive response. Key recommendations of that report include: the federal government should make childhood obesity prevention a national priority; industry and media should develop a healthy marketplace and media environment; community stakeholders and health care providers should work toward building healthy communities and improving access to obesity prevention services in primary-care settings; schools should develop healthier environments that promote both a healthful diet and regular physical activity; and parents and caregivers should foster a healthy family and home environment (IOM, 2005). All of these supportive environments have the potential to collectively promote energy balance—healthful eating behaviors, regular physical activity, and decreased sedentary behaviors—to help children and adolescents achieve a healthy weight while protecting their normal growth and development. One of the fundamental findings identified in the Health in the Balance report was the need to develop a stronger evidence base to more efficiently and effectively guide childhood obesity prevention interventions (IOM, 2005). This report focuses on the continued development of that evidence base through targeted research, ongoing surveillance and monitoring, and widespread evaluation.

STUDY BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

Subsequent to the release of the Health in the Balance report, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation requested that IOM conduct a study to assess the nation’s progress in preventing childhood obesity and to engage in a dissemination effort promoting the implementation of the report’s findings and recommendations through three symposia held in different regions of the country. The dual purpose of convening each symposium was to begin to galvanize obesity prevention efforts among local, state, and national decision makers; community and school leaders; health care providers; public health professionals; corporate leaders; and grassroots community-based organizations, as well as to apprise the committee of the experiences and insights of the broad variety of partnerships and activities related to preventing childhood obesity throughout the nation.

FIGURE 1-1 Comprehensive approach for preventing and addressing childhood obesity.

NOTE: Other relevant factors that influence obesity prevention interventions are culture and acculturation; biobehavioral interactions; and social, political, and historical contexts. See Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2.

SOURCES: Adapted from IOM (2005); CDC (2006a).

To respond to this task, IOM appointed the Committee on Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity, which comprised 13 experts in diverse disciplines including nutrition, physical activity, obesity prevention, pediatrics, family medicine, public health, public policy, health education and promotion, community development and mobilization, private-sector initiatives, behavioral epidemiology, and program evaluation. The IOM committee held six meetings during the course of the study and a variety of sources informed its work. The committee obtained information through a comprehensive literature review, three regional symposia, and two public workshops.

Regional Symposia

The three regional symposia provided an opportunity for the committee to become informed about the numerous ongoing and innovative programs and policy changes being implemented throughout the nation. The symposia provided valuable insights into the challenges, barriers, and facilitating factors that may either hinder or promote the implementation and evaluation of a range of school-, community-, public-sector-, and industry-based efforts. Several crosscutting themes emerged from all three symposia: forge strategic partnerships; educate stakeholders; increase resources; and empower local schools, communities, and neighborhoods (Box 1-1).

In collaboration with the Kansas Health Foundation, the committee held its first symposium, Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Focus on Schools, June 27 and 28, 2005 in Wichita, Kansas. Approximately 90 individuals who are active in childhood obesity prevention efforts in the Midwest and who represented a range of stakeholder perspectives and innovative practices in the school setting participated in the symposium, including teachers, students, principals, health educators, dietitians, state and federal health and education officials, food service providers, community leaders, industry representatives, and academic researchers. The discussion at the symposium focused on exploring the barriers and opportunities for sustaining and evaluating promising practices for creating a healthy school environment (Appendix F).

In partnership with Healthcare Georgia Foundation, the committee held its second symposium, Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Focus on Communities, October 6 and 7, 2005, in Atlanta, Georgia. The symposium brought together a broad range of individuals and organizations involved in community-based efforts in the southeastern United States and included federal, state, and local health officials; students and teachers; community leaders; faith-based partners; and representatives of nonprofit youth-related organizations. The symposium focused on obtaining an understanding of how neighborhood and community grassroots efforts are mobilized; exploring the roles of city, county, and state agencies; and iden-

|

BOX 1-1 Discussion Themes from the Institute of Medicine Regional Symposia June 27–28, 2005, Wichita, Kansas, Focus on Schools October 6–7, 2005, Atlanta, Georgia, Focus on Communities December 1, 2005, Irvine, California, Focus on Industry

|

tifying additional steps that stakeholders can take to overcome barriers to evaluation efforts (Appendix G).

In collaboration with The California Endowment, the committee held its third regional symposium on December 1, 2005, in Irvine, California. Recognizing that the health of individuals is closely linked to the consumer marketplace and the messages disseminated by the media, this symposium focused on the specific IOM report recommendations for stakeholders within industry and the media to explore the roles and responsibilities of the many relevant industries in encouraging and promoting healthy lifestyles for children, youth, and their families. Approximately 90 individuals active in childhood obesity prevention efforts and representing a range of stakeholder perspectives—representatives from food, beverage, and restaurant companies; marketing firms; physical activity and entertainment companies; the media; community leaders; health care professionals; public health educators; foundation leaders; state and federal government officials; researchers; and consumer advocates—participated in the symposium (Appendix H).

Additional Resources

Two additional public sessions provided input from federal government representatives, community-based organizations, and other interested stakeholders. The committee also sought information from a broad array of print and electronic sources, including peer-reviewed published research in public health, medicine, allied health, psychology, sociology, education, evaluation, and transportation; reports, background papers, position statements, and other resources (e.g., legal briefs and websites) from the federal government, state and local governments, professional societies and organizations, health advocacy groups, interest groups and trade organizations, and international health agencies; textbooks and other scientific reviews; federal and state legislation; and news releases on relevant topics.

The committee and IOM staff performed searches of relevant bibliographic databases including MEDLINE, AGRICOLA, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Cochrane Database, EconLit, ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center), PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica), TRIS (Transportation Research Information Services), and LexisNexis. The results of these searches were limited to sources published from 2004 to 2006, to supplement the 2005 IOM report. Additional references were identified from the reference lists found in major review articles, key reports, websites, and relevant textbooks. The committee members, workshop presenters, consultants, and IOM staff also supplied references that were considered for this report.

Scope of the Report

This report summarizes the findings of the regional meetings; provides an evaluation framework for assessing progress in childhood obesity prevention efforts for different sectors, settings, and contexts; assesses progress on the specific recommendations presented in the Health in the Balance report; and offers recommendations on expanding evaluation efforts and utilizing evaluation results to support and inform future childhood obesity prevention efforts in the United States. It is beyond the scope of this report, however, to comprehensively examine progress in childhood obesity prevention across a variety of sectors. Rather, the committee’s approach was to provide an overview of progress in different sectors and contexts, combined with an examination of evaluation approaches that could further progress. The report has undergone an independent and comprehensive peer-review process that is a hallmark of the National Academies before it was published by the National Academies Press.

OBESITY-RELATED TRENDS

Obesity Trends in U.S. Children and Youth

Since the 1970s there has been a steady and dramatic increase in overweight and obesity in the entire U.S. population. In 1991, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had documented through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) that four states had adult obesity prevalence rates of 15 to 19 percent and that no states had rates at or above 20 percent. By 2004, seven states had adult obesity prevalence rates of 15 to 19 percent, 33 states had adult obesity rates of 20 to 24 percent, and nine states had adult obesity rates of 25 percent or greater (CDC, 2005a).

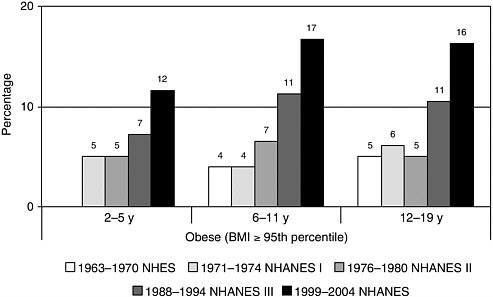

Obesity rates among American children and youth have also increased significantly. Between 1963 and 2004, obesity rates quadrupled for older children, ages 6 to 11 years (from 4 to 19 percent), and tripled for adolescents, ages 12 to 19 years (from 5 to 17 percent) (Figure 1-2) (CDC, 2005b; Ogden et al., 2002, 2006). Between 1971 and 2004, obesity rates increased from 5 to 14 percent in 2- to 5-year-olds (Figure 1-2) (Ogden et al., 2006).3 Given these trends, it does not appear that the Healthy People 2010 target of reducing childhood obesity to 5 percent of the population (DHHS, 2000, 2004) will be reached by 2010.

At present, one-third (33.6 percent) of American children and adolescents are either obese or at risk of becoming obese (Ogden et al., 2006). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data show that the national obesity prevalence for 2- to 19-year olds was 13.9 percent in 1999–2000, which increased to 15.4 percent in 2001–2002 and to 17.1 percent in 2003–2004. In 2003–2004, 16.5 percent of 2- to 10-year olds were at risk of becoming obese (Ogden et al., 2006).

Between 1999–2000 and 2003–2004, the prevalence of obesity among girls increased from 13.8 to 16.0 percent and among boys increased from 14.0 to 18.2 percent (Ogden et al., 2006). Obesity prevalence rates in children and youth reveal significant differences by sex and between racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups (Chapter 3) (Ogden et al., 2006). By 2010, it is projected that an estimated 20 percent of children and youth in the United States will be obese if the current trajectory continues (Sondik, 2004).

FIGURE 1-2 Obesity prevalence among U.S. children and adolescents by age and time frame, 1963 to 2004.

NOTE: Data for 1963 to 1965 are for children ages 6 to 11 years; data for 1966 to 1970 are for adolescents 12 to 17 years of age instead of 12 to 19 years. In this report, children with BMI levels at or above the 95th percentile of the CDC age-and sex-specific BMI curves for 2000 are referred to as obese, and children with BMI levels at or greater than the 85th percentile but less than the 95th percentile are referred to as being at risk for obesity. These cutoff points correspond to the terms overweight and at risk for overweight, respectively, that CDC uses for children and youth.

NHES=National Health Examination Survey; NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCES: CDC (2005b); Ogden et al. (2002, 2006).

Economic Costs

In 2004, health care spending in the United States represented an estimated 16 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), or $1.9 trillion, which translates to $6,280 per person (Smith et al., 2006). By 2015, the U.S. government forecasts that health care expenditures will reach $4 trillion, or nearly 20 percent of the nation’s GDP (Borger et al., 2006). Thorpe and colleagues (2004) estimated the increases in obesity-attributable health care spending from 1987 to 2001 and found that increases in obesity prevalence alone accounted for 12 percent of the growth in health care spending. Increases in the proportion of and spending for obese adults relative to the proportion of and spending for normal weight adults ac-

counted for 27 percent of the rise in inflation-adjusted per-capita health care spending during that time period, of which spending for diabetes accounted for 38 percent of the increase; spending for hyperlipidemia accounted for 22 percent; and spending for heart disease accounted for 41 percent.

Based on 1998 to 2000 data from BRFSS, an estimated 5.7 percent of medical expenditures were attributable to obesity (Finkelstein et al., 2003, 2004). For the Medicare and Medicaid populations, the expenditure percentages were higher: 6.8 and 10.6 percent, respectively. The higher percentage for Medicaid recipients reflects the higher prevalence of obesity among individuals of lower socioeconomic status (SES). Among the states, the percentage of medical expenditures attributable to obesity ranged from 4.0 percent in Arizona to 6.7 percent in Alaska and the District of Columbia. In ten states, the percentage of Medicaid spending attributable to obesity was equal to or greater than 12 percent (Finkelstein et al., 2003, 2004).

Total health care spending for children who receive a diagnosis of obesity (a small subset of the 17.1 percent of U.S. children considered to be obese) is approximately $280 million per year for those with private insurance and $470 million per year for those covered by Medicaid. The national costs for childhood-related obesity (including those who do not receive a diagnosis) are estimated to be $11 billion for private insurance and $3 billion for those with Medicaid. The medical costs for a child who is treated for obesity are approximately three times higher than those for the average insured child (Thomson Medstat, 2006).

ISSUES IN ASSESSING PROGRESS

In response to the rising prevalence and economic costs of childhood obesity, efforts are increasingly being initiated to address this public health concern. However, these efforts are not being consistently evaluated thereby limiting the opportunity to learn from them. The opportunity and the responsibility at hand are the development of a robust evidence base that can be used to deepen and broaden childhood obesity prevention efforts.

Evaluation serves to foster collective learning, accountability, and responsibility, and to guide improvements in obesity prevention policies and programs. As further discussed in Chapter 2, the committee uses the term evaluation to denote a systematic assessment of the quality and effectiveness of an initiative, program, or policy. Evaluation results can be used to identify and scale up those efforts that are successful in achieving desirable outcomes (e.g., improving diets, increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviors, and numerous other intermediate outcomes), refine those that need restructuring and adaptation to different contexts, and revamp or discontinue those found to be ineffective. Harnessing the resources needed

to support evaluation involves a commitment by many sectors and stakeholders to work toward the goal of improving population health.4

Two reviews of childhood obesity prevention interventions and activities indicate that far too few programs are being evaluated. Shaping America’s Youth—a public-private partnership formed in 2003 in cooperation with the Office of the Surgeon General, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Diabetes Association, the Nutrition Department of the University of California at Davis, and numerous sponsoring private-sector companies—released a summary report of the first national registry of programs addressing childhood physical inactivity and excess weight (Academic Network, 2004). The report is based on the information provided by the 1,090 programs in the registry serving an estimated 4.6 million children. Even though funders stated that the availability of outcome measures was the primary criterion for funding awards, only one-half (53 percent) of the programs indicated that they had quantifiable outcome measures (Academic Network, 2004).

A similar pattern was observed in a recent review of the childhood obesity prevention literature by Flynn and colleagues (2006). Of 13,000 reports that described programs to promote healthy weight in children, only 500 provided adequate information about their implementation to identify promising practices. That review highlighted a large number of potentially useful interventions that are not being properly evaluated (Lobstein, 2006).

To encourage and expand evaluation efforts, it is important to take into consideration some of the issues that will need to be addressed. A further analysis of and additional detail about these considerations and other challenges is provided in Chapter 2:

-

Evaluation is often not a priority for individuals and organizations that are developing a new policy, program, or intervention. With a focus on making changes, many programs do not take the time to assess the baseline status or measure outcomes5 that could provide insights into whether the particular mechanism of change is effective. Often, evaluation is viewed as labor-intensive, expensive, and

|

4 |

Population health is concerned with the state of health of an entire community or population as opposed to that of an individual and focuses on the interrelated factors that affect the health of populations over the life course, and the distribution of the patterns of health outcomes (Health Canada, 2001; IOM, 2003). |

|

5 |

An outcome is the extent of change in targeted policies, institutions, environments, knowledge, attitudes, values, dietary and physical activity behaviors, BMI, and other conditions between the baseline measurement and subsequent points of measurement over time (Chapter 2). |

-

technically complex and is not perceived as a responsibility for a small-scale program in a school or community setting.

-

Realistic outcomes need to be assessed. Not every new program or policy should be expected to achieve significant changes in BMI levels, particularly within the short time period in which outcome data are usually collected. Short-term and intermediate outcomes should be realistic and easy to measure and should be targeted to the specific intervention (Chapter 2). Examples of intermediate outcomes include increased time spent in physical activities, reduced time spent in sedentary activities such as viewing television or playing videogames, and increased physical fitness levels (Box 1-2).

-

Resources for evaluation are often scarce. Programs and initiatives frequently exist on minimal funding, particularly at the local level. Technical assistance and resources designated for evaluation efforts are needed with an emphasis on practical and less costly methods of evaluation.

-

Collaborative efforts need to be strengthened and a systems approach needs to be used to support obesity prevention. Frequently, efforts are focused on a single program or intervention and do not examine links to other interventions within the same school or community. A systems approach to health promotion and childhood obesity prevention offers the opportunity to develop and evaluate interventions in the context of the multiple ongoing efforts (Green and Glasgow, 2006; Midgley, 2006). Systems thinking among key stakeholders is needed to promote and sustain meaningful and enduring changes (Best et al., 2003a). However, evaluation methods for a systems approach are currently not well developed (Best et al., 2003b) and deserve further attention.

OVERVIEW OF THE REPORT

This report examines progress in preventing childhood obesity with an emphasis on the surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation of all programs, policies, and interventions used to prevent childhood obesity. The committee introduces an evaluation framework for childhood obesity prevention in Chapter 2 and provides a detailed examination of the key issues relevant to assessing the broad range of pertinent short-term, intermediate, and long-term outcomes. Chapter 2 also provides the committee’s recommendations, which are further discussed with specific details on implementation steps in the remainder of the chapters. Chapter 3 focuses on issues relevant to diverse populations particularly those that are salient for high-risk groups, individuals of low SES, and racial/ethnic minority populations. The concepts introduced in Chapter 3 are carried through into the subsequent

|

BOX 1-2 Obesity Prevention Goals for Children and Youth The goal of obesity prevention in children and youth is to create—through directed social change—an environmental-behavioral synergy that promotes the following: For the population of children and youth

Forindividual children and youth

Because it may take a number of years to achieve and sustain these goals, intermediate goals are needed to assess progress toward reducing the rates of obesity through policy and system changes. Examples include:

SOURCE: IOM (2005). |

chapters, which also focus on examples of progress in obesity prevention across specific sectors of activity: federal, state, and local governments (Chapter 4); a range of private-sector industries (Chapter 5); communities, including foundations, nonprofit and voluntary organizations, and health care professionals (Chapter 6); schools (Chapter 7); and families at home (Chapter 8). These chapters also provide recommendations for next steps in developing and enhancing data sources, evaluation measures, and other assessment tools. The report concludes in Chapter 9, with a focus on the actions that can assist the nation with moving forward in achieving rapid, effective, and meaningful progress to reduce obesity and improve the health status of children and youth.

REFERENCES

Academic Network. 2004. Shaping America’s Youth. Summary Report 2004. Portland, OR. [Online]. Available: http://www.shapingamericasyouth.org/summaryreportKMD_PDFhr.pdf?cid=101 [accessed February 10, 2005].

Best A, Moor G, Holmes B, Clark PI, Bruce T, Leischow S, Buchholz K, Krajnak J. 2003a. An integrative framework for community partnering to translate theory into effective health promotion strategy. Am J Health Behav 18(2):168–176.

Best A, Moor G, Holmes B, Clark PI, Bruce T, Leischow S, Buchholz K, Krajnak J. 2003b. Health promotion dissemination and systems thinking: Towards an integrative model. Am J Health Behav 27(Suppl 3):S206–S216.

Borger C, Smith S, Truffer C, Keehan S, Sisko A, Poisal J, Clemens MK. 2006. Health spending projections through 2015: Changes on the horizon. Health Aff 25(2): w61–w73.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2005a. Obesity Trends: U.S. Obesity Trends 1985–2004. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/trend/maps/index.htm [accessed March 6, 2006].

CDC. 2005b. QuickStats: Prevalence of overweight among children and teenagers, by age group and selected period—United States, 1963–2002. MMWR 54(8):203. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5408a6.htm [accessed February 11, 2006].

CDC. 2006a. A Public Health Framework to Prevent and Control Overweight and Obesity. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 2006b. Overweight and Obesity: State-Based Programs. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/state_programs/index.htm [accessed May 17, 2006].

DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2000. Nutrition and overweight. Focus area 19. In: Healthy People 2010, Volume II, 2nd ed. [Online]. Available: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/pdf/Volume2/19Nutrition.pdf [accessed February 7, 2006].

DHHS. 2004. Nutrition and Overweight. Progress Review. [Online]. Available: http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/2010prog/focus19/Nutrition_Overweight.pdf [accessed February 6, 2006].

Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. 2003. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: How much, and who’s paying? Health Aff W3(Suppl):219–226.

Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. 2004. State-level estimates of annual medical expenditures attributable to obesity. Obes Res 12(1):18–24.

Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, Mutasingwa D, Wu M, Ford C, Tough SC. 2006. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: A synthesis of evidence with “best practice” recommendations. Obes Rev 7(Suppl 1):7–66.

Green LW, Glasgow RE. 2006. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof 29(1):126–153.

Health Canada. 2001. The Population Health Template: Key Elements and Actions that Define a Population Health Approach. [Online]. Available: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/phdd/pdf/discussion_paper.pdf [accessed April 17, 2006].

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lobstein T. 2006. Comment: Preventing child obesity—An art and a science. Obes Rev 7(Suppl 1):1–5.

Midgley G. 2006. Systemic intervention for public health. Am J Public Health 96(3):466– 472.

Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. 2002. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. J Am Med Assoc 288(14):1728–1732.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. 2006. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. J Am Med Assoc 295(13): 1549–1555.

Smith C, Cowan C, Heffler S, Catlin A, National Health Accounts Team. 2006. National health spending in 2004: Recent slowdown led by prescription drug spending. Health Aff 25(1):186–196.

Sondik E. 2004 (January 21). Data Presentation. Healthy People 2010 Focus Area Progress Review: Nutrition and Overweight. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Thomson Medstat. 2006. Childhood Obesity: Costs, Treatment Patterns, Disparities in Care, and Prevalent Medical Conditions. Research Brief. [Online]. Available: http://www.medstat.com/pdfs/childhood_obesity.pdf [accessed February 2, 2006].

Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Howard DH, Joski P. 2004. The impact of obesity on rising medical spending. Health Aff W4(Suppl):480–486.