6

Communities

As noted in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), childhood obesity prevention efforts are ultimately about strengthening com munity capacity and mobilizing community resources and involvement. Whether the community in question is large or small, rural or urban, or termed a neighborhood or barrio, it will inevitably comprise smaller relational networks that include faith-based organizations; worksites; schools; and a variety of government, nonprofit, and voluntary organizations. This chapter uses the term community to denote a geographic entity but acknowledges the strengths and opportunities brought about by groups of people who are linked by social ties; who share common interests, perspectives, and ethnic or cultural characteristics; and who engage in joint action in particular geographic locations or settings (MacQueen et al., 2001).

Communities across the nation are increasingly aware of the childhood obesity epidemic, and this awareness is being transformed into active efforts to improve community access to foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet and increase opportunities for regular physical activity. However, the extent of these changes and the degree to which city councils, local businesses, schools, faith-based organizations, local health departments, and other organizations with a stake in the health and quality of life of children and youth are actively engaged in this issue may vary widely.

The community-based approach to the prevention of childhood obesity

builds on the reality that communities have numerous resources and assets that, if they are mobilized strategically, can directly affect the health and well-being of children and adolescents. These resources and assets can be accessed through the nonprofit organizations that work directly with children and youth. Planning and community development agencies that determine the physical design and use of resources in the built environment, such as paths, parks, and neighborhoods, can make the built environment more user-friendly and thus encourage physical activity. Health care professionals and systems through which primary care services are delivered can address childhood obesity as part of their regular delivery of care. Faith-based organizations, community coalitions, foundations, and worksites can address community and family well-being and are increasingly doing so. Schools are also a vital asset that serve as a link between families and communities and have the capacity to strengthen and reinforce childhood obesity prevention strategies and initiatives and will be discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 7.

The present Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee recommends increased efforts to address the community-based recommendations presented in the Health in the Balance report (Box 6-1) and to incorporate an evaluation component into all policies, programs, and initiatives. This chapter highlights the key actions that need to be taken to activate a community’s assets around the common goal of preventing childhood obesity. It begins with a brief review of key strategies associated with effective community-based prevention efforts. That review is followed by examples of progress that focus on mobilizing communities, improving the built environment, and enhancing the role of health care providers and the health care system in childhood obesity prevention. The chapter concludes with recommendations for guiding communities to assess their progress in establishing promising childhood obesity prevention efforts.

KEY ELEMENTS OF COMMUNITY-BASED STRATEGIES

Although communities may vary widely in their demographics and resources, efforts to engage communities in promoting healthy lifestyles generally involve active grassroots efforts that build on the strengths of the residents and the locale. Mobilizing community participation, developing partnerships, and creating synergistic actions were some of the many themes that emerged from the discussions at the committee’s symposium, Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Focus on Communities, held in Atlanta, Georgia, on October 6 and 7, 2005, in collaboration with the Healthcare Georgia Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) (Appendix G). The key elements of community-based strategies are discussed below.

|

BOX 6-1 Recommendations for Communities from the 2005 IOM report, Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance Community Programs Local governments, public health agencies, schools, and community organizations should collaboratively develop and promote programs that encourage healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity, particularly for populations at high risk of childhood obesity. Community coalitions should be formed to facilitate and promote crosscutting programs and community-wide efforts. To implement this recommendation:

Built Environment Local governments, private developers, and community groups should expand opportunities for physical activity, including recreational facilities, parks, playgrounds, sidewalks, bike paths, routes for walking or bicycling to school, and safe streets and neighborhoods, especially for populations at high risk of childhood obesity. To implement this recommendation: Local governments, working with private developers and community groups should

|

Leadership

Committed and sustained leadership is a common and essential element emerging from promising community-based efforts to address childhood obesity. At a minimum, leadership is viewed as the investment of adequate resources and the commitment of the institutions and organizations that engage in obesity prevention efforts. The sustainability of community-improvement initiatives has been attributed to leaders’ transition from a

Community groups should

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Transportation should

Health Care Pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and other clinicians should engage in the prevention of childhood obesity. Health care professional organizations, insurers, and accrediting groups should support individual and population-based obesity prevention efforts. To implement this recommendation:

SOURCE: IOM (2005). |

focus on projects addressing the symptoms of societal problems (e.g., chronic disease outcomes) to a focus on changing the underlying cultures, incentives, and settings that give rise to these symptoms (Norris and Pittman, 2000). Because of the multiple sectors and stakeholders involved in childhood obesity prevention, leadership on this issue can come from the private or the public sector: from government leaders, health care professionals, school administrators and staff, community residents, and local business leaders. Leaders at the forefront of change in this area are often inspired by

a personal health problem or by an interest in health promotion. Individual and organizational leadership are needed as driving forces in sustaining collaborative efforts, dedicating resources, and working to change social norms that support healthier lifestyles.

Building Community Coalitions

Community coalitions consist of public- and private-sector organizations, together with individual citizens, working to achieve a shared goal through the coordinated use of resources, leadership, and action and the provision of direction in these areas. The synergistic effects of these collaborative partnerships result from the multiple perspectives, talents, and expertise that are brought together to work toward a common goal. However, challenges exist in developing and refining appropriate methods to evaluate the impact of coalition efforts on a variety of outcomes (Fawcett et al., 2000; Lasker et al., 2001; Roussos and Fawcett, 2000; Shortell, 2000). The efforts needed to prevent childhood obesity require a diverse set of skills and expertise—from renovating community recreational facilities to developing multimedia campaigns to promote healthy lifestyles. Because childhood obesity prevention is central to the health of the community’s children and youth, the development of community coalitions is a particularly relevant means of addressing this issue.

The characteristics of successful coalitions include focusing on a well-defined and specific issue, determining common goals, and keeping the coalition focused on providing leadership and direction rather than micromanaging the solutions (Kreuter et al., 2000). All these characteristics are attainable for community coalitions focused on childhood obesity prevention. The diverse set of community organizations and businesses that need to be involved to address childhood obesity includes more than just those stakeholders in the traditional health-related disciplines. These other organizations and businesses that are stakeholders include the building industry, food and beverage companies, the restaurant and food retail sectors, the entertainment industry and the media, the educational community, the public safety sector, transportation divisions, parks and recreation departments, environmental organizations, community rights advocates, youth-related organizations, foundations, employers, and universities, among others. Many stakeholders who might not have considered childhood obesity prevention as an area of interest now find that they have an important role to play in working toward healthier communities. Nevertheless, these organizations face challenges in developming and maintaining community coalitions. These challenges include effectively addressing competing priorities, transforming organizational cultures, and identifying sustainable funding sources.

Cultural Relevance

Building on a community’s cultural assets to enhance childhood obesity prevention efforts is fundamental to the promotion of grassroots involvement and the sustainability of policies, programs, and initiatives. The extent to which culturally competent adaptations are made can greatly affect intervention and policy outcomes (Chapter 3). Culturally appropriate enhancement strategies can be categorized as peripheral (developing packaging to appeal to a particular group by using certain colors, images, graphics, pictures of group members, or titles), evidential (presenting data and information documenting the impact of the relevant health issue on a specific group), linguistic (increasing accessibility by using the preferred language or dialect of the group), constituency based (drawing directly on the experiences of group members through their inclusion as project staff or their substantive engagement as decision makers), and sociocultural (integrating the group’s normative attitudes, values, and practices into messages and approaches) (Hopson, 2003; Kreuter et al., 2003).

Sufficient Resources and Sustained Commitment

Community-wide childhood obesity prevention efforts require careful planning and coordination, well-trained staff, and sufficient resources. Success is greatly enhanced by community engagement in the issue, which can take a great deal of time and effort to achieve. Insufficient resources may result in messages and other planned campaign interventions that are inadequate to achieve the exposure necessary to change the awareness, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors of target groups over time, especially among high-risk populations. Furthermore, a sustained commitment is needed from community leaders, as implementing the changes necessary to alter the physical environment can be both time and resource intensive. For example, the revision of city zoning or planning policies may require extensive time, including the time required to engage community residents, organizations, and businesses in discussions on the proposed changes.

Focus on Safety

Safety is an important construct of the social environment that is likely to influence childhood obesity prevention efforts (Lumeng et al., 2006). Crime rates and residents’ perceptions of neighborhood safety will affect the likelihood that people will walk or bicycle in their neighborhoods. These barriers include both “stranger danger” and “traffic danger,” which are important influences on the decisions that parents make regarding their children’s outdoor play and mode of transportation to school and which also influence the decisions that adolescents make regarding walking or

cycling for transport (Carver et al., 2005). Many of the ongoing walk-to-school efforts (e.g., the Safe Routes to Schools program) began as efforts to address child safety concerns. It is anticipated that both community safety and obesity prevention efforts would mutually benefit from attempts to enhance the community environment and that other benefits would also ensue.

Community-Based Participatory Research

Developing effective intervention actions in communities involves the activation of community group members to take ownership and influence the content and implementation of interventions, the evaluation process, and the dissemination of findings. These concepts are often grouped under the rubric community-based participatory research. This research paradigm recalls the historical roots of public health, in which problems were identified and addressed through collaboration with the public or community for the common good (Israel et al., 1998). By nature, community-based participatory interventions are culturally competent and congruent with the needs and values of a target group because the methods emerge from affected communities as well as university, government, and foundation partners. As discussed in Chapter 3, this is an area of particular relevance for planning, implementing, and evaluating culturally relevant interventions involving racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse subpopulations at high risk for obesity and related chronic diseases.

Building on Multiple Social and Health Priorities

As discussed in Chapter 3, childhood obesity prevention may not rank high as a priority for some communities and neighborhoods that are facing more immediate concerns such as poverty, crime, violence, underperforming schools, and limited access to health care. The opportunity in these communities is to identify and support efforts that can produce many potential benefits; for example, improving playgrounds and recreational facilities may enhance safety, reduce crime, increase physical activity, and improve quality of life. Finding common ground may serve as a key element in garnering sufficient investment for sustained efforts. The challenge is that many of these efforts are resource intensive and require significant political commitment and social support to be accomplished. Building and strengthening the partnerships between organizations working to empower communities can result in collective efficacy, which has been described as “the willingness of community members to look out for each other and intervene when trouble arises” (Cohen et al., 2006). A recent study found that adolescents living in communities with higher levels of collective efficacy had

lower body mass index (BMI) levels than those living in communities without a strong sense of connection. These differences remained significant even while the level of neighborhood disadvantage was held constant. This suggests that even youth living in neighborhoods of higher socioeconomic status may be adversely affected when they lack a connection to their community (Cohen et al., 2006).

EXAMPLES OF PROGRESS IN PREVENTING CHILDHOOD OBESITY IN COMMUNITIES

Given that the United States has approximately 36,000 incorporated cities and towns and many more locales (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006), the committee can provide only selected examples of the array of positive changes that are occurring throughout the nation in response to childhood obesity. As sufficient outcome data with which to evaluate the effectiveness of various policies, programs, and interventions are not yet available for most of the efforts, the descriptions provided are intended to highlight the many and varied efforts that have been and that are being made to address the problem of childhood obesity. They are characterized here as promising practices rather than best practices because sufficient evidence to directly link the effort with reducing the incidence or prevalence of childhood obesity and related co-morbidities is lacking.

Mobilizing Communities

Communities that promote healthy lifestyles and that actively engage their citizens in improving access to opportunities for healthful eating and regular physical activity draw on the talents, resources, and energies of multiple community stakeholders. As noted earlier, efforts to prevent childhood obesity compete with many other efforts to address health and social priorities for the scarce resources that are available at the local level. Furthermore, challenges often arise when attempts are made to coordinate programs under completely different administrative structures (e.g., schools and local health departments) within the community, state, and region. However, these challenges can be effectively confronted in many communities. Programs and initiatives at the community level often work to engage children, youth, and adults in obesity prevention efforts focused on all age groups.

Community Programs and Initiatives

The nature and breadth of community-based programs and initiatives vary widely and may involve community youth organizations, voluntary

health organizations, and public-private partnerships. Programs may also range from multi-city and well-resourced efforts sponsored by corporations or national organizations to efforts sponsored by individual communities engaging in specific projects or programs such as building a playground or expanding bike trails. Likewise, the scope of the evaluation may be modest or sophisticated, and the outcome indicators or performance measures may differ depending on the purpose for which they are intended (Chapter 2). Evaluation methodologies may range from research-based efforts with multiple comparison groups to assessments using more modest outcome measures, such as implementing a policy that supports a capital improvement project to build a new community playground where parents can engage in physical activity with their children.

A number of national youth-related organizations are working with their multiple local chapters to incorporate obesity prevention efforts and goals into their programs, often with the support of foundation or corporate sponsors. For example, Girl Scout councils have developed partnerships with community parks and recreation departments, sports organizations, as well as schools and colleges for physical activity instruction and facilities. Girl Scout programs that are focused on healthy lifestyles include shape UP! and GirlSports (Girl Scouts, 2006). Additionally, the Girl Scouts organization conducted focus group research with online surveys of more than 2,000 8- to 17-year-old girls to explore how they view obesity, how they define health, and what motivates them to lead a healthy lifestyle (Girl Scout Research Institute, 2006).

Other examples are also available. The YMCA has instituted YMCA Activate America™, a long-term commitment to obesity prevention that focuses on improving their programs; providing community leadership; and developing strategic partnerships with universities, government, and corporations (YMCA, 2006). The Boys and Girls Clubs of America feature a number of fitness-related programs, including Triple Play: A Game Plan for the Mind, Body and Soul. The Coca-Cola Company and Kraft Foods Inc. have sponsored that program with the goal of increasing healthy habits and physical activity, and promoting healthful diets (BGCA, 2006). At the IOM committee’s symposium in Wichita, Kansas, students presented a local 4-H-sponsored mentoring program, Kansas Teen Leadership for Physically Active Lifestyles, in which high school students engage with elementary school children in after-school and summer programs focused on promoting physical activity and healthful eating (Sparke et al., 2005).

Community centers, after-school programs, and summer camps are often used as sites for obesity prevention interventions. For example, the GEMS (Girls Health Enrichment Multisite Studies) set of research-based studies has examined a variety of approaches (e.g., dance, team building, games, aerobics, nutrition education, and reduced television viewing) that

are being implemented in community settings to engage 8- to 10-year-old African-American girls in obesity prevention and management (Baranowski et al., 2003; Beech et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2003; Story et al., 2003).

Faith-based organizations are also becoming more engaged in promoting healthy lifestyles. The leaders of many faiths are realizing that messages about physical health and spiritual health are congruent. Indeed, participants at the IOM committee’s symposium on healthy communities in Atlanta described several efforts being undertaken by different faith-based groups to promote health (Appendix G). This process often starts with the minister addressing his or her own health concerns as well as encouraging congregation members to make healthful nutrition and physical activity choices as a way of demonstrating their concern for others and the church family. Congregations are encouraging members to bring healthier meals to church potluck gatherings and are sponsoring health fairs, cooking and exercise demonstrations, physical activity classes, and informational sessions on how to improve the health of the congregation. Others are partnering with local health departments or other health care providers to offer health screenings at places of worship, a setting where people may feel more comfortable than they would in a health clinic. Some congregations have parish nurses or ministers who provide health information, facilitate health promotion activities, and conduct health screenings for congregational members (Brudenell, 2003; Chase-Ziolek and Iris, 2002). Research-based efforts are evaluating the effectiveness of faith-based approaches to obesity prevention; for example, a program called Healthy Body Healthy Spirit is an intervention funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to increase physical activity and the levels of consumption of fruits and vegetables among African Americans recruited through churches (Resnicow et al., 2005).

National efforts that work at the community level often involve successful collaborations among federal agencies, corporations, and community-based, youth-related organizations (Chapters 4 and 5). The numerous ongoing public-private collaborations include Action for Healthy Kids (a collaborative public-private effort focused on changes in schools and involving a number of partners including Aetna Foundation, the American Public Health Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the Department of Education, the Kellogg’s Fund, the National Dairy Council, the National Football League, the National PTA, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and USDA) (Action for Healthy Kids, 2006) and the 5 A Day for Better Health Program (a national public-private partnership with multiple collaborators including the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, Association of State and Territorial Directors of Health Promotion and Public Health Education, CDC, National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity, National Cancer Institute, Pro-

duce for Better Health Foundation, Produce Marketing Association, United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Association, and USDA (PBH, 2006) (Chapter 4). Other national initiatives include NikeGO, sponsored by Nike, Inc. (Nike, 2006); Girls on the Run, sponsored by New Balance and the Kellogg Company (Girls on the Run, 2006); America on the Move® (2006), a nonprofit organization that promotes small lifestyle changes to increase physical activity and reduce calorie intake, with multiple sponsors including PepsiCo and Cargill; and the Women’s National Basketball Association’s Be Smart - Be Fit - Be Yourself program for youth (WNBA, 2005).

Evaluations of these programs vary in scope. For example, the America On the Move Foundation’s assessment strategy includes scientific research in clinical environments of America On the Move programs conducted through the University of Colorado’s Center for Human Nutrition; evaluation of the national online program for individuals and groups based on pre- and post-intervention data and on programs customized for specific settings; and survey data collection through national and state-based instruments of individuals’ health-related knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors, including actual physical activity levels (through the use of stepometer data) (Wyatt et al., 2004).

Numerous state and federal programs operate at the local level. For example, six cities, five counties, and three American Indian tribes have received funding through the STEPS to a HealthierUS Cooperative Agreement Program (Steps Program) that enables communities to develop an action plan, a community consortium, and an evaluation strategy that supports chronic disease prevention and health promotion (DHHS, 2006) (Chapter 4). Cooperative extension services are another example of federal, state, and local partnerships that work through land-grant universities and local extension offices to disseminate information to families and individuals and engage communities to work on a range of nutrition- and agriculture-related issues (CSREES, 2006). Additionally, federal food and nutrition programs, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), provide opportunities to convey information about dietary and physical activity changes to the parents of young children and to the employees working in these programs (Box 6-2; Chapters 4 and 8). Furthermore, work site efforts focused on improving employee health often have direct and indirect benefits for children and youth by providing parents with information that they can use to influence the nutrition and physical activity behaviors of their children. For example, the National Business Group on Health has developed a tool kit for employers and fact sheets for parents focused on healthy weight for families (NBGH, 2006).

|

BOX 6-2 Engaging Adult Health and Social Services Providers as Vehicles for Social Norm Changes In 1999, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) funded a childhood obesity prevention initiative called Fit WIC to support and evaluate social and environmental approaches to preventing and reducing obesity in preschool children (USDA, 2005). California was one of the four state Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) programs that participated in the pilot program evaluation. The Fit WIC program, implemented through California WIC clinics and evaluated by the University of California at the Berkeley Center for Weight and Health (Crawford et al., 2004), compared six WIC sites (three of which served as intervention groups and three of which served as control groups) that participated in a pilot staff wellness intervention program to improve staff effectiveness in preventing childhood obesity. The intervention approaches focused primarily on supporting beneficial behaviors rather than on weight loss and on motivating staff members to eat healthfully and to be more physically active throughout the work day. Among the organizational changes at WIC sites were healthy food choices (e.g., fresh fruit or vegetables) when refreshments were served at meetings or celebrations and integrating 10-minute physical activity breaks into regular staff meetings or at certain times of the work day. Compared with the staff at the control site, the staff in the intervention group perceived greater support for their efforts to make healthful food choices available at the worksite and to engage in physical activity and reported substitutions in the types of foods served during meetings and the placement of a priority on physical activity in the workplace. Staff members at the intervention site were also more likely to counsel WIC participants to engage in physical activity with their children and reported that they believed that they had greater sensitivity in handling weight-related issues. This study underscores the potential reach of fitness promotion (Glasgow et al., 1999) in organizations serving high-risk groups, given the multiplier effect, that is, the positive influence of healthy provider behavior on clients. SOURCES: Abramson et al. (2000); Frank et al. (2000); Lewis et al. (1986); Thompson et al. (2003). |

Foundations

Foundations are active partners in many community-based obesity prevention efforts. As the funding sources for grantees at the community and grassroots levels, foundations may require that an evaluation plan be submitted with the grant application. For example, The California Endowment’s Healthy Eating/Active Communities (HEAC) initiative funds several community demonstration projects to implement programs promoting physical activity and healthful eating in six low-income communities

throughout California (California Endowment, 2006). As part of the HEAC initiative, adolescents involved in the Youth Study are using digital cameras to provide images of their physical activity and eating environments and will engage in discussions about evaluating the need for environmental changes (Craypo et al., 2006).

Active Living by Design and Active Living Leadership initiatives, through the support of RWJF are using the expertise of a diverse group of professionals—such as urban planners and designers, environmentalists, asthma control activists, leisure and travel industry specialists, economists, and public policy advocates and decision makers—to explore the possibilities for greater community efforts to increase the levels of physical activity among children and youth (Active Living Leadership, 2004). Recently, RWJF launched the Healthy Eating Research initiative, which places special emphasis on building a field of research that will benefit children in low-income and different racial/ethnic populations at the highest risk for obesity by improving their eating habits (RWJF, 2006). Some foundations coordinate their efforts with those of industry, government, and other sectors to fully leverage resources and scale up programs and initiatives. For example, the Alliance for a Healthy Generation, described in Chapters 2, 5, and 7 is designed as an extensive collaborative effort involving foundations, nonprofit organizations, industry, and state government leadership. However, evaluations are needed to assess the effectiveness of the Alliance.

One of the strengths of local, statewide, and regional foundations is their familiarity with the cultural assets and demographic characteristics of the areas they serve and their ability to focus grants and funding opportunities on innovative projects that build on local assets. The committee, through its three regional symposia, had the opportunity to learn more about the community-based obesity prevention programs and initiatives funded by the Kansas Health Foundation, the Sunflower Foundation, the Healthcare Georgia Foundation, the Missouri Foundation for Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Some corporate foundations are also active partners in childhood obesity prevention efforts at the community level (Chapter 5).

As foundations across the nation continue in their commitment to childhood obesity prevention, it is important to build on their strengths and to identify the ways in which foundations can be most effective. For example, foundations often have greater flexibility in their funding mechanisms than government agencies so that they can more quickly explore untested or promising approaches or respond more rapidly to evaluations of natural experiments (discussed later in this chapter). Further, foundations are often effective in partnering with organizations that can sustain the activity if it is proven efficacious, efficient, and culturally and socially appropriate.

Evaluating the efforts of foundations will include consideration of the long-term sustainability of funding for projects related to obesity prevention and the extent to which obesity prevention initiatives are a funding priority.

Developing and Strengthening Community Coalitions

As noted earlier, the development of community coalitions is a particularly relevant approach to the prevention of childhood obesity. The efforts of groups and individuals with many diverse areas of expertise are needed to move obesity prevention efforts forward and can have a synergistic effect when coordinated. Community coalitions relevant to childhood obesity prevention often focus on broader but related issues, such as encouraging healthy lifestyles or preventing chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, in children, youth, and adults. The healthy communities movement, and its outgrowth, the Coalition for Healthier Cities and Communities, provide an example of an initiative focused on health promotion and disease prevention that measures community-based outcomes including improved cardiovascular health, reductions in crime, reduction of the rates of teen pregnancy, and declines in the numbers of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections (Norris and Pittman, 2000).

Another example is the Border Health Strategic Initiative (Border Health ¡SI!), a diabetes prevention intervention that involves several communities along the Arizona–Mexico border, which developed community coalitions focused on building partnerships with local universities, community health workers (promotores de salud), and other community stakeholders. The initiative used the REACH 2010 community-based participatory research model to focus on implementing policy changes in schools, involving planning and zoning commissions, in long-range community planning, and organizing an annual community forum for elected and appointed local officials to discuss policy changes to promote health (Meister and de Zapien, 2005) (Chapter 3).

Examples of community coalitions and initiatives (Boxes 6-3 and 6-4) highlight the range of stakeholders and the importance of leadership in initiating and sustaining community efforts. Often, the mayor or another key community leader can galvanize the political will and multistakeholder support that is needed to build a coalition focused on improving the health of the community. Generally, these efforts focus on all citizens, including children and youth.

Community coalitions often conduct local surveys and assessments as they get under way to provide baseline information; follow-up assessments can then be performed during the course of the coalition’s work to assess progress. The Bexar County (Texas) Community Health Collaborative be-

|

BOX 6-3 Sonoma County (California) Family Activity and Nutrition Task Force In 1998, the Sonoma County Family Activity and Nutrition Task Force was initiated to bring together individuals, professionals, and community-based organizations to focus on the health, nutrition, and physical activity levels of children in the county. The task force works through four subcommittees:

In February 2006, the Task Force received a five-year grant from Kaiser Permanente to implement the Healthy Eating Active Living-Community Health Initiative in two local communities, South Park and Southwest Santa Rosa. Phase 1 of the project will involve the development of a community action plan, and Phase 2 will implement and evaluate the plan over four years. SOURCE: Sonoma County (2006). |

gan with a baseline health needs assessment in 1998. That assessment was followed up by a comparable assessment effort in 2002 (Health Collaborative, 2003). The assessments, conducted in collaboration with the University of Texas Health Science Center, provided detailed information on a range of health issues in various areas of the county. Follow-up plans have involved the use of the community health planning tool MAPP (Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships) (NACCHO, 2004) to develop and implement a strategic plan for next steps in improving the county’s health status (Health Collaborative, 2003; San Antonio Metropolitan Health Department, 2006).

Because childhood obesity may be a vast and complex issue for a community organization with limited time and resources, it may be necessary for a community group to focus on a single, manageable project to yield tangible results and measurable outcomes. For example, a number of community initiatives are focused on building a playground or changing a local school district’s policies related to the availability and sale of competi-

|

BOX 6-4 Examples of Community Initiatives and Coalitions

SOURCES: ACT!vate Omaha (2006); CLOCC (2006); Fit City Madison (2006); Health and Wellness Coalition of Wichita (2005); Health Collaborative (2006). |

tive foods in schools (Chapter 7). Even if the group disbands after a project is completed, progress has been made and awareness has increased among all of the stakeholders involved. Although the progress that results from a collaboration is difficult to measure, collaborations have important benefits such as empowering community residents and local organizations and increasing the community’s capacity to address a problem (Kreuter et al., 2000).

Enhancing the Built Environment

The built environment represents the human-made elements of the physical environment (e.g., the buildings, the infrastructure, and arrangements in space and the aesthetic qualities of these elements). Over the past 50 years, the physical environment has changed dramatically, and it is increasingly recognized as a factor contributing to the obesity epidemic

(Brownson et al., 2005; IOM, 2005; Sallis and Glanz, 2006). Relevant features of the built environment include land use patterns and the paths, roads, and other means of transport that link one location with another. Additionally, the built environment encompasses the way in which the interiors of buildings are structured to accommodate or necessitate movement, as well as the structure of the community food environment, which plays a role in determining access to fruits, vegetables, and other foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet (Brownson et al., 2006; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006; Handy et al., 2002; Kahn et al., 2002; TRB and IOM, 2005; Zimring et al., 2005).

Local zoning boards, city planning commissions, capital improvement committees, and many other entities are involved in decisions regarding land use, transportation, building development, and the locations of sidewalks and bicycle and pedestrian paths (TRB and IOM, 2005). Organizations and movements such as Smart Growth and New Urbanism work to facilitate and implement active travel, livable and sustainable communities, mixed land use (e.g., residential, office, and retail space), and the preservation of open space (New Urbanism, 2006; Smart Growth Network, 2003). Latino New Urbanism (2006) is a recent outgrowth of these efforts and involves the consideration of Latino culture in the development of urban properties and land use plans.

Promoting Physical Activity

Communities are becoming more aware of the need to enhance healthy lifestyles for children and youth by offering safe and attractive places in neighborhoods for recreation and play and by promoting active travel. Numerous issues related to the built environment are particularly important for populations at high risk for obesity. In addition, in many locales, fewer recreational facilities are present in low-income neighborhoods than in more affluent areas (Cradock et al., 2005; Sallis and Glanz, 2006). It is thus important to identify the extent of the disparities in access to opportunities for physical activity so that these issues can be addressed. For example, in Boston, Massachusetts, the nonprofit organization Play Across Boston conducted a needs assessment with funding from CDC, that involved a census of the public recreational facilities, as well as the collection of data on the physical activity programs available to children and youth outside of school hours (Hannon et al., 2006). Combining this information with household income and population census data provided insights into the areas where recreational opportunities needed to be enhanced.

Many communities are expanding and improving their playground and gymnasium facilities; adding and restoring walking and biking trails; taking pedestrian issues into consideration when they plan for new road construc-

tion; and involving children, youth, and families in a variety of physical activity-related programs (Sallis and Glanz, 2006). For example, voters in Los Angeles have approved a major bond issue that will support the upgrading of urban parks, and some public school playgrounds in downtown Denver have been converted into community parks (Brink and Yost, 2004).

Examples of nation-wide efforts to change the built environment to encourage physical activity are also available: the PedNet Coalition in Columbia, Missouri (Box 6-5); the work of the PATH Foundation and partners to develop a metrowide trail system for Atlanta and DeKalb County in Georgia (PATH Foundation, 2006); the 1000 Friends of New Mexico initiative that promotes smart growth in Albuquerque (1000 Friends of New Mexico, 2006); and the efforts by the Winnebago Tribe’s (Nebraska) efforts to increase physical activity and develop plans to improve the built environment (Box 6-6). The Partnership for a Healthy West Virginia offers Walkable Communities Workshops that aim to bring together community stakeholders and help them organize their efforts to improve pedestrian safety and the walkabilities of their communities (Partnership for a Healthy West Virginia, 2006).

|

BOX 6-5 PedNet Coalition, Columbia, Missouri The PedNet Coalition is a group of individuals, businesses, and nonprofit organizations working in Columbia, Missouri, to develop and restore a network of nature trails and urban “pedways” to connect residential subdivisions, worksites, shopping districts, parks, schools (including local colleges and the University of Missouri–Columbia), public libraries, recreation centers, and the downtown area. The coalition has developed a plan for a 20-year effort to fully implement the network of trails and paths. Additionally, the coalition sponsors the Walking School Bus program and a number of citywide biking and walking events. Co-founded in April 2000 by the City of Columbia Disabilities Commission and the City of Columbia Bicycle and Pedestrian Commission, the coalition now has more than 5,000 individuals and 75 organizations, businesses, and government agencies as participants. In July 2005, Columbia was selected by the Federal Highway Administration to receive a Non-Motorized Transportation Pilot Program grant, and the PedNet Coalition is providing input into the planning process. The evaluation methods that the PedNet Coalition uses include tracking of the travel mode to school at four elementary schools (twice a year for the past 2.5 years) and tracking of the number of participants at the annual Bike, Walk, and Wheel Week events. SOURCE: PedNet Coalition (2006). |

|

BOX 6-6 Winnebago Tribe Winnebago, Nebraska The Winnebago Tribe, a Native American tribal community in Nebraska, is working to enhance the opportunities for physical activity and improved nutrition in the residential and commercial areas of the community. The nonprofit development arm of the Winnebago Tribe has worked with other community and foundation partners to develop a five-year plan, establish biking and walking support groups, develop community gardening programs, and conduct active living events. One of the goals is to create pedestrian-friendly crossings on a highly traveled highway that separates housing from other areas of the community. The community is involved in planning for mixed-use land development and in implementing other active transport changes. SOURCE: Winnebago Tribe (2006). |

The daily trips that children and youth make to and from school have received considerable attention in many communities as a way to increase students’ physical activity levels (WHO, 2002). Community efforts to increase walking and bicycling to and from school focus on improvements to the built environment—intersections, sidewalks, and bike paths—accompanied by programs to encourage parents and children to consider non-motorized methods of travel. For example, urban design changes resulting from California’s Safe Routes to Schools legislation (e.g., additions and rebuilding of sidewalks and bike paths and improvements in pedestrian crossings) have been found to increase the rates of walking or bicycle travel by children in a survey of parents at 10 elementary schools (Boarnet et al., 2005).

Schools and communities are also promoting walk- or bike-to-school days through programs such as Safe Routes to Schools and CDC’s Kids Walk-to-School program. In Hinsdale, Illinois, a walk-to-school day in 2000 was the beginning of citywide efforts to build new sidewalks and repair existing sidewalks; provide public education on traffic safety issues; and work with transportation engineers, the police force, and others to improve the walkability of the town (Active Living Network, 2005). The federal Safe Routes to School Program, initiated in August 2005 through the transportation reauthorization legislation, provides funds for states and, subsequently, communities to build safer street crossings and establish programs that encourage walking and bicycling to school (FHWA, DoT, 2006).

Enhancing the Community Food Environment

Although information about how the community environment affects the eating patterns of children and youth is limited and more evaluation is needed, efforts are underway to better understand these relationships (Glanz et al., 2005; Moore and Diez Roux, 2006). For example, the RWJF Healthy Eating Research Program mentioned earlier is encouraging solution-oriented research that explores the environmental and policy determinants of healthy eating as strategies for addressing childhood obesity (Story and Orleans, 2006).

Through community advocacy, several cities have shown that it is possible to locate supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods to enhance the neighborhood population’s access to fresh fruits and vegetables (Sallis and Glanz, 2006). The Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative—a public-private partnership of the Food Trust of Philadelphia, the Greater Philadelphia Urban Affairs Coalition, the Reinvestment Fund, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania—provides financing through grants and loans to increase the numbers of supermarkets and grocery stores in underserved communities in Pennsylvania (Food Trust, 2006). The outcomes of this initiative are being evaluated with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Alternative strategies are also being developed to increase the availability, affordability, and access to foods, beverages, and meals that contribute to healthful diets throughout neighborhoods and communities. Community gardens are moving beyond rural and suburban communities into urban areas. For example, the Harlem Children’s Zone, a program and facility designed to provide safe and healthful educational, social, and recreational activities for children and youth, has transformed a vacant lot in New York City into a garden where children work alongside older residents to cultivate and harvest fresh produce and share it with other members of their community (Garden Mosaics, 2006) (Chapter 3).

Mobile markets, such as People’s Grocery in West Oakland, California, sell produce in urban neighborhoods and involve youth interns in selling local produce (Flournoy and Treuhaft, 2005). Neighborhood bus systems have also been developed to link residents with supermarkets. In East Austin, Texas, a bus route provides transportation from a low-income Latino community to two supermarkets (Flournoy and Treuhaft, 2005). Evaluations of these initiatives are needed to determine whether access to healthier foods has increased and, if it has, whether the consumption of these foods replaces less healthful alternatives and the effects of these more healthful food alternatives on long-term behavioral and health outcomes.

The creation of local food policy councils is another strategy that can be used to prevent childhood obesity. A food policy council brings together community stakeholders—including consumers, farmers, food processors,

distributors, food security advocates, educators, and governmental units—to develop policies and projects to improve access to foods that contribute to a healthful diet while also supporting local farmers (Borron, 2003; McCullum et al., 2005; Webb et al., 1998). Municipal or regional food policy councils have been established across the country including in Santa Cruz, California; New Haven, Connecticut; Knoxville, Tennessee; Portland/ Multnomah, Oregon; and Seattle/King County, Washington. Some states also have active food policy councils (McCullum et al., 2005).

The range of issues on which food policy councils or coalitions may focus include the creation and maintenance of farm-to-school programs (e.g., fresh produce from local farms is used in school salad bars and lunches, and school field trips to local farms are promoted); the creation of youth leadership programs that help youth develop skills in gardening and marketing, for example, through projects to develop school-based edible landscaping and produce stands; improvement of the availability of healthful and affordable foods in low-income communities (e.g., the creation or expansion of farmers markets); working on issues related to land use policies and local or regional food production and consumption (e.g., community gardens, community-supported agriculture, seasonal eating plans, and food system education); and the support of legislation, such as zoning laws, that either ban or regulate the location, number, and densities of fast food outlets, quick serve restaurants, and drive-through establishments in cities and municipalities (Borron, 2003; Cohen et al., 2004; Hamilton, 2002; Mair et al., 2005a,b).

Tool kits are available that provide guidance on conducting a community food assessment, defined as “a participatory and collaborative process that examines a broad range of food-related issues and assets in order to inform actions to improve the community’s food system” (CFSC, 2004). These include the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Community Food Security Assessment Toolkit (Cohen, 2002) and the Community Food Security Coalition’s Community Food Project Evaluation Handbook and Community Food Project Evaluation Toolkit (National Research Center, Inc., 2004a,b).

A distinction is made between program-level tools, which are used to measure the changes in individuals who participate in or receive direct services from a community food project, and system-level tools, which measure changes in the food system of a community, city, state, region, or the nation. System-level tools (e.g., community mapping and geographic information systems [GIS]) can be used to inventory and identify the types and ranges of local food resources, such as supermarkets, corner grocery stores, full serve and quick serve restaurants, food banks, food pantries, farmers markets, and community gardens (Algert et al., 2006; McCullum et al., 2005; Pothukuchi et al., 2002). System-level tools can also be used to assess changes in the food system that will increase the availability of

locally grown food in retail stores, increase the availability of supermarkets within walking distance of residents, and increase the presence of or expand the activities of food policy councils (National Research Center, 2004a,b).

Engaging Health Care Providers and the Health Care System

The Health in the Balance report’s discussion of the role of health care professionals and organizations focused on providing counseling, leadership, advocacy, and training (IOM, 2005). A systematic assessment of the progress by the health care sector regarding childhood obesity prevention efforts has not yet been conducted. Such an assessment is one component of the larger effort that is needed to engage health care providers in fostering healthy behaviors in their patients (Green, 2005). Nevertheless, there are examples of how certain components of the health care sector have begun to take a more visible role in formulating policies and implementing innovative programs to prevent childhood obesity.

Efforts are ongoing to explore the factors that may encourage pediatricians in counseling their patients on overweight or obesity or that may hinder them from doing so. A survey of North Carolina pediatricians found that those who classified themselves as thin or overweight had greater difficulty providing their patients with weight counseling than pediatricians who classified themselves as average weight (Perrin et al., 2005). A survey of nurse practitioners in the intermountain area of Utah found that barriers to implementing childhood obesity prevention strategies included perceived parental attitudes regarding a lack of motivation to implement healthful changes; difficulties for families to overcome social norms regarding television viewing, videogame playing, and carbonated soft drink and snack foods consumption; and a lack of time and reimbursement for adequate counseling and patient education (Larsen et al., 2006).

Individual physicians and professional organizations have become involved in promoting and implementing obesity prevention programs at the community and state levels (Box 6-7). The IOM committee noted at the symposia in Wichita and Atlanta that physicians who have been elected as state legislators or who hold leadership positions in the state executive branch are often vocal proponents of obesity prevention measures and actively work to propose relevant legislation. Many professional organizations, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics, provide evidence-based, online patient and provider tool kits and informational websites that help them prevent and manage obesity in children and youth (AAFP, 2004; AAP, 2006) (Chapter 8).

Obesity-related initiatives by major health plans initially focused on treatment options for adults (such as coverage for weight loss drugs or bariatric surgery) but are now increasingly emphasizing obesity prevention

|

BOX 6-7 Physicians as Advocates for Healthy Communities The California Medical Association (CMA) Foundation began its Physicians for Healthy Communities initiative in 2005 to coordinate the obesity prevention efforts of California’s physicians with the healthy eating and physical activity programs run by the California Nutrition Network in schools, community organizations, and local and state government. The California Nutrition Network for Healthy, Active Families is a project of the California Department of Health Services funded by the Food Stamp Program. The CMA Foundation enlisted the support of 40 county medical societies, 37 ethnic physician organizations, and several specialty medical societies. During the first year of the project nearly 150 “physician champions” were identified. In 2006, 250 physician champions were being trained to become educators and advocates for healthy eating and physical activity in schools and communities throughout the state. The CMA Foundation provides physicians with training opportunities, tool kits for working with schools and underserved populations, and guidelines for talking about obesity prevention with patients during patient visits (www.calmedfoundation.org). The CMA Foundation’s Physicians for Healthy Communities Initiative is supported by the California Department of Health Services, Kaiser Permanente, Blue Shield of California, and LA Care Health Plan. SOURCE: CMA Foundation (2006). |

and ofen include a specific focus on children and youth (Kertesz, 2006b; NIHCM Foundation, 2006). A new effort by America’s Health Insurance Plans includes a focus on mini-grants that are awarded to further research on obesity-related interventions. Health plans are developing educational materials and programs for patients and clinicians. For example, CIGNA has developed an online tool kit for physicians to assist them with counseling parents and older youth about childhood obesity (Kertesz, 2006a). Kaiser Permanente has recently instituted BMI as a vital sign that is assessed during clinical visits and as an outcome measure that can be tracked as part of the electronic medical record system (Box 6-8).

Health plans are also involved in community- and school-based programs. In 1998, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts began a youth wellness program, Jump Up and Go!, which involves developing partnerships with community-based organizations to provide physical activity programs, school initiatives, health professional educational components, and educational materials to assist pediatric clinicians with counseling children and their parents (Jump Up and Go!, 2006). Other innovative approaches include the Kaiser Permanente worksite farmers markets in California that offer patients and employees the opportunity to purchase fresh fruits, vegetables, and other foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet

|

BOX 6-8 Kaiser Permanente’s Healthy Eating, Active Living Initiative Kaiser Permanente’s Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) initiative is a multifaceted approach to promoting a healthy lifestyle that integrates prevention-oriented delivery system interventions, community-based initiatives, organizational practice changes, and a media campaign. Delivery system interventions. In 2002, Kaiser Permanente launched the Weight Management Initiative to introduce and evaluate evidence-based clinical practice changes to support prevention and treatment of overweight. Key elements of this initiative include assessment of BMI as a vital sign, physician training programs on counseling strategies, and point-of-care prompts in examination rooms. Community health initiatives. The multisectoral HEAL initiatives bring together community-based organizations, schools, public health departments, and the health sector to work together on change strategies, with an emphasis on making changes in institutional practices, public policy, and the built environment. Organizational practice changes. Efforts are also focused on increasing access to opportunities for physical activity and offering low-calorie high nutrient foods and beverages within Kaiser Permanente medical facilities by sponsoring farmers markets at hospitals and medical office buildings, significantly changing the contents of the vending machines, ensuring that a minimum of 50 percent of vending machine slots supply food and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet, and improving the nutritional quality of foods offered in hospital and medical center cafeterias. Public policy advocacy. Kaiser Permanente has also funded public health advocacy organizations and has backed legislation designed to make it easier for people to be more physically active and have increased access to foods that contribute to a healthful diet. Media campaign. In 2004, Kaiser Permanente launched its Thrive advertising campaign. Intended principally to communicate the organization’s philosophy of prevention and health promotion to current and prospective members, it has also sought to influence social norms with billboards, television advertisements, and radio spots. SOURCES: Kaiser Permanente (2006); Loel Solomon, Kaiser Permanente, personal communications, June 2006. |

(Kaiser Permanente, 2004) (Box 6-8). Kaiser Permanente has also expanded its Community Benefit Program to focus on obesity prevention efforts through its Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) initiative (Kaiser Permanente, 2006).

Coordinating the community benefit efforts of health care organiza-

tions within the community are important, as is concerted involvement in community coalition efforts. Health care organizations can also demonstrate leadership by serving as organizational role models for physical activity and healthful eating practices, which include expanding the availability of low-calorie and high-nutrient foods in worksite vending machines and cafeterias as well as creating incentives for employees to engage in physical activity.

Efforts are under way to consider the types of information that clinicians and other stakeholders need to effectively address childhood obesity (Public Health Informatics Institute, 2005). An example is the All Kids Count program, a national technical assistance program to improve child health and the delivery of immunizations and preventive services through the development of integrated health information systems (Saarlas et al., 2004). Furthermore, regional health networks and electronic health records, which are increasingly being used, may provide sources of data relevant to childhood obesity that would also protect patient confidentiality. For example, western North Carolina Health Network’s Data Link Project provides access to electronic health information for health care providers caring for the same patients across multiple health care institutions. Although this system is not being designed to provide regional aggregate health data search capabilities, such capabilities could be incorporated into the network’s data linkages with the agreement of the participating entities.

Few mechanisms exist to provide accountability for the various components of the health care system in obesity prevention efforts. The committee encourages health care providers and organizations to provide greater leadership in addressing issues related to promoting healthful eating and regular physical activity. The National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality is in the process of developing a national program for recognizing promising clinical practices and clinical partnerships whose efforts have contributed to reducing childhood obesity (NICHQ, 2006).

APPLYING THE EVALUATION FRAMEWORK TO COMMUNITIES

What Constitutes Progress for Communities?

Individual communities across the nation are at different stages of engagement and action in addressing childhood obesity. The committee recognizes that it is not possible to obtain an accurate and systematic assessment of how many communities are fully engaged, how many are only beginning to initiate changes, how many recognize the problem but have not begun to address it comprehensively, and how many have not yet prioritized this issue. It is likely that the attention that childhood obesity is being paid in schools has alerted most communities to this issue. However,

it remains to be determined how many communities have recognized that community stakeholders need to take additional actions.

It is important to emphasize the short-term and intermediate outcomes that can be examined in evaluating changes at the community level. It is not realistic for each community program to reduce children’s BMI levels in a short time frame, nor is this expected; instead, the focus should be on assessing progress toward short-term outcomes (e.g., changing institutional, local, or state policies to support obesity prevention) and intermediate outcomes such as increasing the proportion of children or youth involved in physical activity on a daily basis, increasing the percentage of physical education or recess periods that children or youth spend in moderate or vigorous physical activity, increasing the number of miles of bicycle and walking trails, and increasing access to affordable fresh fruits and vegetables for families (e.g., through the provision of farmers markets in low-income communities and community or school gardens).

Furthermore, communities need to take full advantage of their racial/ ethnic diversity and cultural assets by developing programs and opportunities culturally relevant to the children and adolescents in their communities. Sports activities, dance, foods, and beverages all have distinct cultural relevance that reflect community strength and provide an infrastructure for promoting healthful eating and active living.

The committee identified several important elements in assessing progress in childhood obesity prevention in communities:

-

Collect, analyze, and present specific data for the community to make the case for action to local decision makers. Challenges include knowing how and from where to gather community-level data.

-

Assess interventions that have evidence of effectiveness, and select promising initiatives that can be implemented by programs in the community.

-

Identify funding sources for a new intervention or program; and have the time and the knowledge to identify, apply, and manage the required reporting for external grants.

-

Design an evaluation plan and have sufficient numbers of knowledgeable staff with the skills and time available to measure and document the outcomes of an intervention.

-

Sustain the intervention, particularly after external grant funding has ended.

Applying the Evaluation Framework

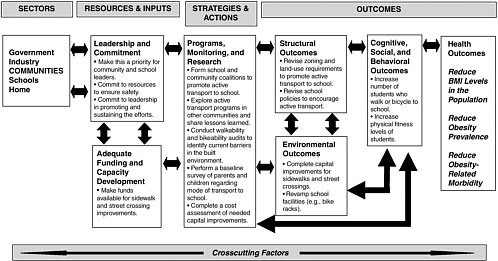

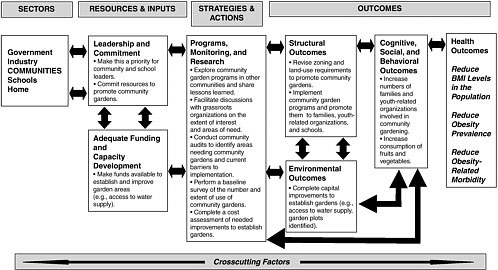

The evaluation framework introduced in Chapter 2 can be used to evaluate community policies and interventions. Two examples of the use of

the framework are provided here: one focuses on active transport to school (Figure 6-1), and the other focuses on community gardens (Figure 6-2). Because of the diverse stakeholders involved in community-level changes, the responsibility for implementing, evaluating, and sustaining an intervention at any point in the framework can rest with a number of different organizations or entities. Indicators of progress in the community are varied and usually focus on short-term or intermediate outcomes that can be addressed by creating a community environment that facilitates physical activity and encourages healthful eating (Box 6-9).

Applying the framework in evaluating community interventions includes multiple components:

-

The leadership, commitment, political will, financial resources, and capacity development, which are crucial as starting points for community change, can come from a variety of public- and private-sector sources at the national, state, regional, and community levels.

-

The strategies and actions needed for community change can involve policy and legislative action, coalition building and collaboration, and program implementation.

-

Structural, institutional, and systemic outcomes for communities include changes in policies and regulations by the local government to improve and invest in active transport and improved access to foods that contribute to a healthful diet (e.g., smart growth initiatives and incentives for the establishment of farmers markets).

-

Environmental outcomes include the addition or enhancement of bicycle or walking paths or playgrounds, changes in traffic intersections or other road-related efforts to improve the walkability of community thoroughfares, as well as increased access to fruits and vegetables.

-

Cognitive, behavioral, and social outcomes relevant to the community sector include the formation of relevant community coalitions, the acquisition of information gained on how to engage in healthy lifestyles by families, increases in the levels of physical activity, and improved nutritional intake.

-

The health outcomes at the community level, as in other sectors, are focused on healthy children and youth and reductions in the prevalence of obesity and its associated morbidities.

NEEDS AND NEXT STEPS IN ASSESSING PROGRESS

Although a number of communities around the country are actively involved in improving opportunities for physical activity and healthful eating, there is an urgent need to scale up these efforts and to mobilize many

|

BOX 6-9 Examples of Community Indicators

SOURCES: California Department of Health Services (2006); Chapter 4. |

more towns, cities, and counties to become actively involved in childhood obesity prevention. The following sections detail the next steps and implementation actions for communities.

Promote Leadership and Collaboration

Civic, social, and faith-based leaders in a community can galvanize action by local residents, businesses, schools, and organizations to improve the quality of life and the focus on nutrition and physical activity in the community. Often, many community groups may be working independently on individual projects and initiatives. A greater coordination of efforts and communication about the range of efforts has the potential to leverage these efforts to reach more individuals and families and can also encourage other groups to initiate nutrition and physical activity interventions. Leadership can also be shown in the organizational modeling of fitness and nutrition policies and practices. In all of these efforts, it is important that evaluation be a priority. Indeed, leadership is demonstrated in the resources and emphasis that are placed on evaluation and on the dissemination of the results of those evaluations.

Develop, Sustain, and Support Evaluation Capacity and Implementation

Increase Funding and Technical Assistance Support for Evaluation

Evaluation at the program level often takes a backseat to implementing the intervention itself. Therefore, it is necessary for programs to design evaluation components into the implementation plan from the outset of the effort.

Programs may be overwhelmed by the concept of evaluation, which may seem to involve complex and time-consuming tasks, especially given quality assurance reports or grant reporting requirements that they must fulfill. Evaluations are often directed at assessing the process, that is, quantifying the service or program delivery efforts (such as the number of units or clients) rather than at the more important questions regarding an assessment of the influence of the program or service.

Evaluation needs to be an essential component of community actions. Clear requirements for evaluation as well as strong technical assistance should be included as part of the grant application process in government agencies and private foundations. Funding agencies should provide technical assistance to grantees as they develop an evaluation component or establish guidelines and selection criteria requiring community-based organizations to subcontract with academic institutions or other trained and experienced professionals for evaluation services. This was the model that CDC’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) initiative used and is consistent with a community-based participatory research model in that the resources are controlled by the community-based organization rather than the academic institution.

Increasingly, it is recognized that tools are needed to assist communities with conducting their evaluations. For example, CDC’s Physical Activity Evaluation Handbook is based on other program evaluation efforts in public health and on the work of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (CDC, 1999, 2002; Martin and Heath, 2006). Additional straightforward evaluation tools for community-based programs need to be developed and disseminated.

Many organizations can barely summon the resources to implement new efforts and so do not include funds for evaluations in their budget planning. In addition to requiring that evaluations be included as an integral component of the program or intervention from the outset, there is a need for foundations, states, federal agencies and others to provide the funding and resources needed to ensure that evaluation efforts are implemented. The Healthy Carolinians community microgrants program, for example, provides funds to encourage and catalyze health promotion activities. Organized at the county level, Healthy Carolinians, a state-wide network of public-private partnerships, awarded small grants (approxi-

mately $2,000 each), collected final reports, and conducted surveys to evaluate the program and collate the lessons learned (Bobbitt-Cooke, 2005).

Develop and Widely Disseminate Training Opportunities

The formal training of individuals working in public health at the local level is highly variable (IOM, 2003). For example, in the United States, less than half of the 500,000 individuals in the public health workforce have had formal training in a public health discipline, such as epidemiology or health education (Baker et al., 2005; Turnock, 2001). An even smaller percentage of these professionals have formal graduate training from a school of public health or other public health program. At the local level the public health capacity for chronic disease control is also often low (Frieden, 2004). These findings suggest that there is a significant need for on-the-job training for public health practitioners, including a significant focus on evaluation of chronic disease interventions that address obesity.

Several practitioner focused training programs are promising. CDC has developed a useful six-step evaluation framework that can guide the process of conducting program evaluation (CDC, 1999, 2002). The Evidence-Based Public Health course, developed in Missouri, trains professionals to use a comprehensive approach for program development and evaluation from a scientific perspective (Brownson et al., 2003; Franks et al., 2005; O’Neall and Brownson, 2005). Each year CDC also sponsors a set of physical activity and public health courses operated by the University of South Carolina Prevention Research Center.

The committee encourages existing training programs to assess their focus on chronic disease and childhood obesity prevention and determine the effectiveness of these programs. Furthermore, federal and state agencies, foundations, and voluntary health organizations should increase the resources needed to widely disseminate and implement effective training programs.

Develop and Support Community-Academic Partnerships

Communities and academic institutions have different knowledge, skills, and strengths that can inform and complement each other when they partner to design, implement, and evaluate interventions to prevent childhood obesity. Academic institutions have strengths in intervention design and evaluation, and familiarity with grant funding, and expertise in writing and disseminating intervention outcomes. Local partners bring indispensable knowledge of their community’s issues, cultures, and worldviews, institutions, resources, and priorities. Successful intervention collaborations respect both types of knowledge.

At the committee’s Atlanta symposium, a county commissioner in Wilkes County, Georgia, discussed how county officials approached the Medical College of Georgia and the University of Georgia to help them address the county’s growing obesity rate. After conducting a community health needs assessment in conjunction with the universities, a community task force developed a Wilkes Wild About Wellness community effort that included activities and interventions at local churches and worksites and in other locations (e.g., health fairs, summer day camps, after-school nutrition programs, faith-based wellness classes, and health screenings). The university was involved with the initial assessment of the community’s health needs as well as with the design and evaluation of the intervention components (Hardy, 2005; Policy Leadership for Active Youth, 2005). The outcomes being evaluated include the number of participants, the amount of shelf space in grocery stores devoted to food items that contribute to a healthful diet, the extent of print media coverage of health issues, and the addition of walking paths and other environmental changes.

Other examples of successful partnerships can also be found. A community-based intervention in Florida with multiple collaborators (including the American Heart Association, Boys and Girls Clubs of Central Florida, the Food and Drug Administration, and Albertsons, Inc.) used the expertise of nursing students and faculty at the University of Central Florida to assist with the implementation of the intervention and to help plan and carry out the evaluation (DeVault and Watson, 2005). In Tarrant County, Texas, a partnership of Texas Christian University and community participants (including partners from the Cornerstone Community Center, the Tarrant Area Food Bank, and the Texas Cooperative Extension Tarrant County) worked together to design a program, Table Talks, that was presented in English and Spanish. The program provided information on family meal preparation and physical activity and nutrition classes. The pre-and post-intervention measures of that program included knowledge about nutrition and exercise, physical activity patterns, and dietary intake recall (Frable et al., 2004).

Key components of university-community partnerships that address childhood obesity prevention include participatory processes that engage key community members and that structure the partnership to ensure that equal attention and weight are given to the contributions of both the university and the community (Greenberg et al., 2003; Thompson and Grey, 2002). Many communities with diverse populations are cautious about the research conducted with the members of those communities. However, if the intervention is designed and implemented with the community as a partner, this community reluctance can be reduced (Chapter 3). Mechanisms to encourage these types of community-academic partnerships are needed and can be built into federal, state, and foundation grant requirements.

Enhance Surveillance, Monitoring, and Research

The vast numbers of communities, their varied organizational structures, and the independence of each community organization makes it difficult to assess the extent of community change directed toward reducing rates of childhood obesity and the effects of the change on a variety of childhood obesity outcomes. Few national surveys assess community actions, and the tracking of policy changes at the local level is limited. Furthermore, tools that can assist communities with evaluating new programs or conducting self-assessments are only beginning to be fully developed.

Expand Surveillance for Community and Built Environment Outcomes