7

Schools

Childhood obesity prevention efforts have primarily focused on the school environment because nearly all children, ages 5 years and older, spend a large part of their days in school for 9 to 10 months out of the year. Schools are an important setting to enhance students’ dietary intake and physical activity opportunities and to provide relevant education and behavioral change programs. Policies and programs have the potential to influence the behaviors of all the students in a classroom, school, or school district. However, because the nation’s estimated 66,000 public elementary schools, 12,000 middle schools, and 14,000 high schools are often governed at the local school board, town, or district level, it is difficult to systematically evaluate prevention strategies or to disseminate promising strategies, policies, and programs (NCES, 2005). Further, more attention needs to be paid to the provision of low-calorie and high-nutrient foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet and opportunities for physical activity in the child-care, after-school, and preschool environments regarding the.

The Health in the Balance report provided a range of recommendations for schools (Box 7-1) with the goals of creating and maintaining a consistent environment that supports healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity. The report also emphasized the need to help students understand the benefits of healthy lifestyles and the relationship between calorie intake and energy expenditure to achieve energy balance at a healthy weight (IOM, 2005).

|

BOX 7-1 Recommendations for Schools from the 2005 IOM report Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance Schools should provide a consistent environment that is conducive to healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity. To implement this recommendation: USDA, state and local authorities, and schools should

State and local education authorities and schools should

Federal and state departments of education and health and professional organizations should

SOURCE: IOM (2005). |

In June 2005, the committee sponsored the symposium Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Focus on Schools in collaboration with the Kansas Health Foundation and sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Appendix F). The symposium was held in Wichita, Kansas and provided the committee with the opportunity to interact with a range of

stakeholders—teachers, students, principals, health educators, dietitians, after-school personnel, food service providers, industry representatives, state government and community leaders, and researchers—and learn about innovative interventions, challenges in implementing and evaluating school-based and after-school programs, and opportunities for evaluating policies and initiatives. In addition to the symposium, the committee draws from reports, scientific literature, and the media to provide examples of obesity prevention activities in schools for this chapter.

The obesity prevention effort in schools is an active area for change, and the committee recognizes that it can capture only a small proportion of the obesity prevention-, physical activity-, and nutrition-related policies and programs being implemented. This chapter focuses on assessing progress and ensuring that evaluations are conducted so that the most promising approaches can be identified and disseminated. As noted in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), there is a relative paucity of scientific data on obesity prevention efforts in schools. Teachers, schools, school districts, states, and the nation are in the midst of many exploratory efforts and new interventions, which provide opportunities to build the evidence base in order for promising efforts to be replicated and scaled up. Additionally, it is important that efforts found to be ineffective are either revised or discontinued, so they do not use resources that can be more effectively used for other efforts.

The multitude of actions revolving around nutrition and physical education in schools is a positive step forward. However, as detailed in a recent report examining state and regional obesity prevention-related policies, much remains to be done to provide a consistent healthy school environment that promotes energy balance for children and youth (TFAH, 2005). Although many states are addressing nutrition-related issues, these efforts are not being implemented in all states, and limited attention is focused on concurrently increasing physical activity levels and reducing sedentary behaviors.

Highlights from the 2005 Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) report indicate that, as of the time of publication of the report:

-

Six states (Arkansas, Kentucky, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas) have mandated nutritional standards for school meals and snacks that are stricter than current USDA requirements.

-

Eleven states (Arizona, California, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia) have established nutritional standards for competitive foods sold in schools. Many of these changes had occurred recently with six states setting requirements for competitive foods since 2004.

-

All states except South Dakota have physical education require-

-

ments for students; however Illinois is the only state that requires physical education for every grade in schools on a daily basis.

-

Four states (Arkansas, Illinois, Tennessee, and West Virginia) have passed legislation that allows schools to measure students’ body mass index (BMI) levels as part of health examinations or physical education activities.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

One of the greatest challenges for school-based obesity prevention efforts may also be an opportunity to rapidly advance progress. As noted above, because schools are primarily controlled and administered at the local level, there are challenges in disseminating effective prevention interventions and for schools to learn about what has been effective or ineffective in other schools or school districts. However, this same lack of coordination between educational institutions may also provide the opportunity for a broad array of highly innovative approaches to emerge or for similar approaches to be implemented within many different settings. If evaluation efforts can be applied to these various approaches, there is an opportunity to rapidly expand the evidence base. In the absence of evaluation, this multiplication of efforts and approaches has less opportunity to support effective policies, programs, and initiatives or ensure the efficient use of resources.

Time and financial resources were two key barriers to the implementation of obesity prevention interventions identified by teachers and school administrators at the committee’s regional symposium (Appendix F). The school year and school day are finite, and teachers report competing demands on their time. In particular, the school day is filled with nationally and state-mandated academic subjects, and there has been an increased emphasis in recent years on teaching to meet academic testing requirements. Teachers and school officials also reported that the effort to comply with the academic requirements set forth in the No Child Left Behind Act that was signed into law in 2002 (DoEd, 2006a) and similar state or local mandates often results in a de-emphasis on physical education and nutrition education programs.

Financial resources are also limited and are spread across many different competing priorities. Unless an individual school or school district has established health promotion as a high priority, financial resources will be insufficient to hire and train highly qualified physical education teachers, after-school program personnel, health educators, and school health professionals (e.g., school nutritionists and school nurses) and equip them with the space, equipment and supplies, and curricula that they require for creating a healthy school environment. Even when health promotion and obesity

prevention have been identified as high priorities, school funding may still be insufficient to effectively implement and evaluate relevant policies, programs, and initiatives.

As with other sectors that affect the health and wellness of children and youth, schools are only one setting where young people spend part of their day and their year. Therefore, an important challenge is to promote and achieve collaborations between many stakeholders that provide healthful messages and opportunities. These collaboration should involve parents; after-school and child-care programs; media; sports organizations; nonprofit organizations that sponsor after-school, evening, and summer activities (e.g., Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, and Boys and Girls Clubs); and industry. Nevertheless, although schools are attractive partners and settings for collaborative initiatives, they are also asked to address many other health and social issues (e.g., violence prevention, sexual health education, and substance abuse prevention). Extra demands may create more competition for the time that children and adolescents spend in school and the human and financial resources needed to implement nutrition and physical activity programs.

Assessing progress in childhood obesity prevention in the school setting is assisted by many surveillance systems, surveys, and self-assessment tools—some of which have been actively used for 10 to 15 years. The discussions in this chapter frequently refer to the major surveillance systems or tools that are being used to assess progress in obesity prevention in the school setting (Table 7-1; Chapter 4; Appendixes C and D). However, as noted later in the chapter, most surveys do not comprehensively cover all school grades and local-level data are limited.

EXAMPLES OF PROGRESS IN PREVENTING CHILDHOOD OBESITY

With the myriad of obesity prevention initiatives occurring across the nation, the committee can provide only selected examples of innovative practices. This section examines the progress toward meeting the recommendations presented in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), provides examples of relevant efforts to fulfill the recommendations, and, where available, discusses the tools and strategies being used to evaluate and assess that progress.

Creating an Environment Conducive to Healthy Lifestyles

School wellness plans and councils are the focus of current efforts to address the comprehensive issues of creating and sustaining schools throughout the nation that promote healthy lifestyles. The Child Nutrition and

TABLE 7-1 Overview of Surveillance and Monitoring Systems

|

Surveillance System |

Description |

|

School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS) |

SHPPS has been conducted every six years by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1994. SHPPS provides state, school district, school, and classroom information that is aggregated at the national and state levels. Of greatest relevance to childhood obesity prevention are the sets of questions about health education, physical education and activity, food service, and school policy and the school environment. |

|

School Health Profiles (SHP) |

SHP is a biennial survey, which CDC has conducted since 1994, of a representative sample of middle and senior high schools in a state or school district. Principals and health education teachers are asked to respond to surveys that encompass a range of school health issues. |

|

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) |

YRBSS collects self-reported data on the risk behaviors primarily of 9th- to 12th-grade students, and has been conducted every two years since 1991. CDC provides technical assistance to states and municipalities that conduct the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) at state or local levels concurrent to CDC conducting the YRBS at the national level. In 2005, weighted results (requiring a 60 percent or higher response rate) were collected for 40 states and 21 school districts (Eaton et al., 2006). |

|

School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study (SNDA) |

SNDA has been conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in the 1991–1992 and 1998–1999 school years and data for SNDAS III were collected in the 2005 school year. The study examines calorie content, fat content, pricing, student participation, and other elements of school food sales for a nationally representative sample of elementary, middle, and high schools. |

|

School Health Index (SHI) |

The School Health Index (SHI), developed and promoted by CDC, is an eight-module assessment tool aimed at assisting individual schools examine and evaluate their comprehensive school health and safety policies. Two sets of SHI modules—one for elementary schools and the other for middle and high schools—have been developed. |

WIC Reauthorization Act (Public Law 108-265) was initiated and passed by Congress in 2004 and requires school districts participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) or School Breakfast Program (SBP) to establish local school wellness policies by the beginning of the 2006–2007 school year (CNWICRA, 2004). Local school wellness policies address a

range of health-related issues, including nutrition and physical activity. The Act includes a plan for assessing the implementation of local school wellness policies supported by $4 million in appropriated funds (Chapter 4).

A number of organizations have developed model wellness policies and components of those policies. For example, the National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity has developed model nutrition and physical education policies that states and school districts can use and customize to local situations (NANA, 2006). The National Association of State Boards of Education in collaboration with the National School Boards Association has developed the resource Fit, Healthy, and Ready to Learn, which provides sample policies that reflect promising practices (NASBE, 2006). USDA has assembled reference materials in its online Team Nutrition: Local Wellness Policy database (USDA, 2006b). Action for Healthy Kids, in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed the Wellness Policy Tool, which complements the Team Nutrition website and which assists school districts in identifying appropriate policy options (Action for Healthy Kids, 2006). Both websites also include evaluation resources. Additional resources include the wellness policy evaluation checklists developed by state agencies in Pennsylvania and Texas (Pennsylvania School Boards Association, 2006; Texas Department of Agriculture, 2006).

Most evaluations conducted to date have focused on outcome measures related to developing and implementing policy changes at the school or school district level (e.g., structural, institutional, and systemic outcomes). Future evaluations should examine the effect of these changes on students’ cognitive, dietary, and physical activity behaviors, as well as health outcomes. It is unclear at this point whether most schools will have the resources required to conduct further evaluations that focus on behavioral and health outcomes.

A presentation at the committee’s symposium in Wichita, Kansas highlighted the joint efforts of the Kansas Department of Education and the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. The two departments are collaborating to develop model wellness policies for school districts throughout the state (Appendix F). Additionally, tools are being developed that individual school districts can use to evaluate the implementation of their wellness policy and a state-level database will be used to track the implementation of these policies in each district. Technical assistance will be provided to the school districts, and efforts are under way to sustain local changes through school health advisory councils. In the next few years, as school wellness policies are adopted and promoted, it will be important to systematically evaluate the implementation of the wellness policies and to focus on sustainability issues.

The development and implementation of coordinated school health

programs are the emphases of the funding and technical assistance available through CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health (Kolbe et al., 2004). Currently 23 states receive funding focused on the coordinated school health program model, which has eight components, including nutrition, physical education, creating a healthy school environment, and health promotion for staff.

Many states and cities are currently enacting legislation that focuses on multiple aspects of enhancing a healthy school environment. For example, in June 2005 South Carolina’s legislature and governor approved legislation that focused on school nutrition, physical activity, and health education particularly in elementary schools (Box 7-2). Arkansas took an early lead in this effort with a focus on assessing BMI levels, implementing changes in school foods, and promoting physical activity (Ryan et al., 2006).

Additionally, a number of organizations, foundations, government agencies, corporations, and others are partnering with schools on efforts that affect multiple aspects of the school environment. Examples of these

|

BOX 7-2 South Carolina’s Students’ Health and Fitness Act of 2005 Beginning in the 2006–2007 school year:

SOURCE: South Carolina General Assembly (2006). |

broad-based initiatives include Action for Healthy Kids (a public-private partnership with state-based coalitions) and the Healthy Schools Program sponsored by the Alliance for a Healthier Generation (a joint effort of the American Heart Association and the William J. Clinton Foundation with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) (Chapters 2 and 5).

Improving School Food and Beverage Nutrition

The food and beverages sold or available in schools through the federal meal programs, as competitive (à la carte) items in the school cafeteria, in vending machines, in school stores, or in the classroom have been the focus of obesity prevention efforts in many localities (CSPI, 2006; Story et al., 2006). Policies related to the types of foods and beverages available in elementary, middle, and high schools generally differ, with more restrictive policies implemented for the lower grades. Many states are developing and implementing state nutrition standards for the foods and beverages served and sold in schools (see for example, Andersen et al., 2004; Connecticut State Department of Education, 2006). Certain cities and localities, such as Chicago and Philadelphia (Box 7-3) are enacting requirements stricter than those mandated by state law.

In 2004, the School Health Profiles (SHP) survey found that carbonated soft drinks, sports drinks, or fruit drinks were offered for sale in vending machines in 95.4 percent of the schools in the 27 states for which weighted data were available. Similarly, bottled water was offered by 94.3

|

BOX 7-3 Overview of Nutrition Standards of the School District of Philadelphia

SOURCE: Philadelphia Comprehensive School Nutrition Policy Task Force (2002). |

percent of the schools (Kann et al., 2005). In future SHP surveys, it will be important to track trends in the type of foods and beverages available for purchase by students.

Despite all the attention being paid to improving the nutritional quality of the foods and beverages provided in schools, however, the committee heard at the Wichita symposium that food service managers face ongoing challenges in improving school nutrition. These include insufficient funding, the use of sole-source contracts, open campuses where students can choose to leave schools to eat, a lack of nutrition education, short meal periods, and competition with vending machine options (Appendix F). Other barriers that food service managers face include preferences for fast foods, carbonated soft drinks, and salty snacks; the mixed messages sent by school personnel; and school food preparation and serving space limitations (Gross and Cinelli, 2004).

At the more local level, individual schools and school districts have made innovative changes to their menus, food sales, and beverage choices (Box 7-4) (Kojima et al., 2002). One of the challenges, however, has been in disseminating that information. The Produce for Better Health Foundation, in conjunction with 5 a Day and Fresh from Florida, has compiled promo-

|

BOX 7-4 Key Considerations in Improving School Foods and Beverages from the Minneapolis Public Schools Food Service Presentation at the IOM Symposium on Schools

SOURCE: Dederichs (2005). |

tional ideas and implementation models to help food service managers increase students’ fruit and vegetable consumption (PBH, 2005a,b). A recent CDC and USDA publication, Making It Happen: School Nutrition Success Stories, documents some of those changes. Examples include efforts made in Ennis, Montana, where students were involved from the initial planning in 2002–2003 in restocking vending machines and removing brand logos from vending machine signage. The vending services for the Oceanside, California school district were placed under the auspices of the food services program; and the results included healthier options and increased revenue from vending sales for the high school. In McComb, Mississippi, school policies were changed so that fundraising through the sale of candy or other less nutritious food items is not permitted in kindergarten through the eighth grade (USDA, DHHS, and DoE, 2005).

Federal, state, and community programs are increasingly focused on improving the nutritional quality of school foods and beverages—those offered as part of the NSLP and SBP, as well as those sold competitively. As discussed in Chapter 4, USDA’s Team Nutrition program provides technical assistance to school food service personnel and child-care professionals, including Fruit and Vegetables Galore, a tool to assist schools in promoting fruit and vegetable consumption (USDA, 2006c). Additionally, innovative approaches to increase fruit and vegetable availability and consumption are being implemented by students, teachers, food service personnel, and the community through farm-to-school programs and school gardens (Graham and Zidenberg-Cherr, 2005; USDA, 2005). The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), in partnership with USDA, conducts the DoD Fresh program, which in the 2005–2006 school year distributed produce to school foodservice programs in 46 states and more than 100 American Indian reservations (Chapter 4) (David Leggett, USDA, personal communication, July 13, 2006; USDA, 2006a).

Fresh fruits, dried fruits, and fresh vegetables are also being made available to students outside the regular school meal periods through USDA’s Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP). Established as a pilot program in the 2002–2003 school year, the program aims to increase student consumption of fruits and vegetables by increasing the availability of these foods in the school environment (Chapter 4). In 2004, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act (Public Law 108-265) established FFVP as a permanent program and expanded the program from four to eight states and added additional American Indian reservations (UFFVA, 2006); subsequent appropriations legislation in 2006 expanded the program to 14 states, and additional funding for a nationwide program is being sought. FFVP has undergone a preliminary evaluation, and further evaluation efforts are under way (Buzby et al., 2003) (Appendix D). For example, an evaluation of 25 schools in Mississippi that participated in the

FFVP suggests that the distribution of free fruit to middle school students might be effective as a component of a more comprehensive approach to improve dietary behaviors (Schneider et al., 2006). The committee encourages increased funding for implementing and evaluating innovative programs such as the FFVP.

A major focus of recent obesity prevention analyses and efforts has been the competitive foods and beverages—those foods and beverages offered at schools other than those available through the school meals programs (e.g., NSLP, SBP) often through school vending machines (Bachman et al., 2006; California Endowment, 2005; CSPI, 2006; Forshee et al., 2005; Westcott, 2005). In many parts of the country, school districts, localities, and states have set standards for foods and beverages that can be sold, have enacted restrictions on when vending machines are available to students, and in some cases, have removed vending machines from school grounds. Recently, major beverage companies announced an alliance to restrict the sales of some beverages in schools, particularly in elementary and middle schools (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2006) (Chapters 2 and 5).

In a recently published study of competitive foods in schools (Greves and Rivara, 2006) investigators interviewed school district representatives with the largest student enrollment in each state and Washington, DC, and compared the policies with the recommendations in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005). Nineteen of the 51 districts evaluated had policies with requirements that went beyond state or federal requirements, with most having criteria for food and beverage content. Fewer school districts had policies related to portion size, advertising, or fund-raising. Interview questions regarding district policies also indicated that changes in product lines have been made and that snack food and beverage vendors have developed and offer new products (Greves and Rivara, 2006).

IOM is currently conducting a study, sponsored by CDC, to develop recommendations on appropriate nutrition standards for foods that are available, sold, and consumed at school, with attention given to competitive foods and beverages (IOM, 2006a). The committee recommends that Congress, USDA, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) provide leadership in establishing nutrition standards for competitive foods in schools by marshalling the political will needed to develop, implement, and evaluate appropriate standards that are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005.

Evaluating Progress in Improving School Foods and Beverages

National surveys, particularly SHPPS, ask extensive questions about the school food environment. These questions examine the nutritional content of school meal programs and competitive foods, in addition to infor-

|

BOX 7-5 Examples of Survey Questions Related to the Availability of Foods and Beverages Offered in Schools 2006 SHPPS School Questionnaire (CDC, 2006b)

SHP 2006 School Principal Questionnaire (CDC, 2006g)

SHI for Middle and High Schools (CDC, 2005):

|

mation about the foods and beverages sold through other school venues (Box 7-5). For example, the segment of the 2006 SHPPS questionnaire related to food services included 55 questions at the state level, 78 questions at the school-district level, and 88 questions for individual schools,1 with additional questions focused on the foods and beverages sold in vending machines and other school venues (CDC, 2006b). The results of the 2006 survey and future surveys will provide extensive data that can be used to examine trends in the school food environment since 2000. The most recent School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study, SNDA III, is in the process of collecting and analyzing data (Mathematica Policy Research, 2005). When these results become available, they can be compared with the data from the 1991–1992 and 1998–1999 SNDA studies to examine the level of progress made toward improving the nutritional quality of available foods, dietary intake of students, and student participation rates in the federal school meals programs. The focus of the SNDA study is on the federally funded school meal programs with fewer data collected on competitive foods or on vending machine usage.

Individual surveys of school nutrition policies and program implementation are also useful tools for assessing and encouraging progress in preventing childhood obesity. A survey of school food service directors at a sample of high schools in Pennsylvania found that à la carte sales provided an estimated $700 a day to each school food service program, with 85 percent of those programs not receiving financial support from their school districts (Probart et al., 2005). Ninety-four percent of respondents indicated that vending machines are accessible to students, with bottled water being the most commonly offered item (71.5 percent). A survey of vending machine-related policies and practices in Delaware school districts provides similar baseline data against which future progress can be assessed (Gemmill and Cotugna, 2005). Given the number of changes in school foods and beverages, a baseline assessment of nutritional content and sales data against which data from later follow-up assessments can be compared is a useful evaluation tool.

Evaluations of farm-to-school programs to enhance the fruit and vegetable consumption of children and youth have been conducted. For example, Feenstra and Ohmart (2004, 2005, 2006) evaluated farm-to-school salad bar programs in Yolo County, California using a variety of methods: school food expenditures and distributor documentation; interviews and focus groups with students, farmers, school garden coordinators, and food service personnel; a plate wastage study; and digital photographs of student meals. Results showed that the salad bars raised the fruit and vegetable consumption of students. It also found that choice and variety are two important dimensions of school meals; when multiple varieties of fruits and vegetables were provided, children selected them.

Initiatives such as the Team Nutrition program are developing evaluation resources that can be provided to schools, and often include sample data collection instruments. The Team Nutrition school-based evaluation instruments are currently undergoing pilot testing (Murimi et al., 2006).

Other researchers are exploring the factors associated with student purchase of competitive foods, including the timing of school meals, open campus policies, the number of vending machines accessible to students during and after school, and policies regarding the type of food and beverages sold (see, for example, Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2005; Probart et al., 2006).

Increasing Physical Activity

Schools offer the opportunity for children and youth to be engaged in physical activity and to establish the foundation for lifelong habits of incorporating physical activity into their daily lives. However, physical activity is

often not a priority consideration in school, child-care, and after-school policies and practices. Schools, school districts, preschools, and after-school and child-care programs may vary widely in the extent to which they are engaged in promoting regular physical activity. The results of the YRBSS show that the percentage of students in grades 9 to 12 who attended physical education classes on a daily basis decreased between 1991 and 1995 (from 41.6 percent to 25.4 percent) but has since remained relatively constant at approximately one-third of students (25.4 percent to 33 percent from 1995 to 2005) (Eaton et al., 2006). Among the 40 states that participated in this most recent YRBSS, there was a substantial variation in students who attended physical education classes daily (from 6.7 percent to 60.7 percent).

Although, many changes in school policies and practices in improving the nutritional content of the foods and beverages offered to students are occurring, there appears to be less progress in making changes in physical education requirements, enforcing state standards where they do exist, or expanding intramural and other physical activity opportunities.

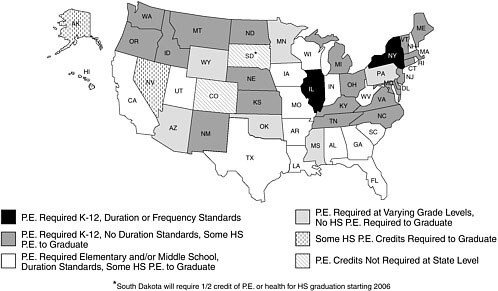

The state policy assessment conducted by TFAH found that in 2004– 2005, 17 states passed legislation, resolutions, or policies aimed at improving their physical education programs (TFAH, 2005). A large proportion of the legislation created task forces to examine and revamp state physical education policies. Further, some states have not yet been able to pass legislation that implements changes in physical education requirements. For example, in Georgia, legislation requiring 150 minutes per week of physical education in kindergarten through the fifth grade and plans for 225 minutes of physical education per week for sixth to eighth graders was defeated upon adjournment of the 2006 legislative session (NetScan, 2006). The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) also found that few states have physical education requirements that specify the duration and frequency of physical education (Figure 7-1) (NCSL, 2006).

The National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE), in partnership with the American Heart Association (AHA), recently released the Shape of the Nation Report on physical education in U.S. schools (NASPE and AHA, 2006). Although physical education is mandated in most states (e.g., 36 states mandate physical education for elementary-school students, 33 states mandate physical education for middle-school students, and 42 states mandate physical education for high-school students), far fewer states specify the number of minutes of physical education per week. Two states (Louisiana and New Jersey) mandate the recommended 150 or more minutes of weekly physical education for students (NASPE and AHA, 2006). Only 15 states require student assessment in physical education (NASPE and AHA, 2006). Health-related physical edu-

cation is the focus in some school districts with an emphasis on developing the skills and interest in lifelong physical activity (Pate et al., 2006).

Recess provides another opportunity in the school day for promoting physical activity among children and youth. In a recent U.S. Department of Education survey of 1,198 public elementary schools, 83 to 88 percent reported providing daily recess for students with the average number of minutes ranging from 27.8 minutes in first grade to 23.8 minutes in sixth grades; among these schools, the rates at which physical education classes were provided on a daily basis ranged from 17 to 22 percent across the elementary grades (Parsad and Lewis, 2006).

Although several organizations monitor state physical education policies, including the Trust for America’s Health and the National Council of State Legislatures (Chapter 2), enforcement of state physical education standards and requirements is more difficult to monitor.

A variety of perceived barriers to increasing physical activity opportunities were shared by stakeholders at the committee’s symposium in Wichita, Kansas (Appendix F). These include a lack of time throughout the school day due to the efforts that schools must make to meet the requirements for standardized testing and a lack of resources to develop or supplement intramural or other physical activity programs. A survey of physical education teachers in Texas working with the Coordinated Approach To Child Health (CATCH) program similarly reported that one of the greatest barriers to providing quality physical education is the low priority it is given relative to the priority given to other academic subjects (Barroso et al., 2005). Large class sizes and inadequate financial resources were also concerns.

Incorporating physical activity into the standard curriculum is a subject of study and exploration. Several programs, including Take 10!®, encourage teachers to allow students to be physically active as they answer questions, cite mathematics facts, or engage in other learning activities (Cardon et al., 2004; Donnelly, 2005; Lloyd et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 2004) (Chapter 3). The effects of implementing school-based and community-based physical activity programs is being examined through various research efforts, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls, a randomized multicenter study involving girls in 36 middle schools across the country (Gittelsohn et al., 2006).

Many opportunities exist to promote physical activity in school and child-care settings. States, school districts, schools, preschools, and after-school and child-care programs should expand opportunities for physical activity. The federal government and state governments have responsibilities in increasing the capacity, standards, and resources needed to implement regular physical activity in schools. The U.S. Department of Education’s Carol M. White Physical Education Program awarded more than

$73 million in grants to schools and communities in 2005, with each of the awards ranging from $75,000 to $650,000 to support physical education programs, including after-school programs, for students in kindergarten through 12th grade (DoEd, 2006b) (Appendix D). These efforts, in addition to those of the CDC and the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports (DHHS, 2006), should be strengthened, coordinated, sustained, and evaluated.

Intramural and Interscholastic Sports and Physical Activity Programs

Limited data are available to assess the extent to which intramural sports programs in schools are changing or the number of schools that are moving beyond competitive extramural athletics to expand opportunities for more students to participate in physical activity clubs. The 2005 Youth Sports National Report Card noted a strong concern about early sports specialization and a highly competitive atmosphere that is more focused on winning than encouraging children and youth to have fun, increase their fitness, or develop important skills (CTSA, 2006).

Awareness of the value of nontraditional physical activity programs as a component of school programs appears to be growing. Activities such as dance classes may attract students who have not shown an interest in other types of physical activity (Chapter 3). For example, West Virginia is incorporating a video-based dance game, Dance Dance Revolution®, into its physical education curriculum for public schools, in partnership with the game’s producer, Konami Digital Entertainment. An evaluation of this effort is being conducted by a consortium that includes West Virginia University, the West Virginia Department of Education, Mountain State Blue Cross Blue Shield, and Konami (Konami Digital Entertainment, 2006).

Efforts to document innovative physical activity policies, programs, and success stories in schools are needed, similar to the efforts by CDC and USDA in documenting examples of changes to school food programs through publications such as Making It Happen: School Nutrition Success Stories (USDA, DHHS, and DoEd, 2005). Further, national surveillance systems should include a more extensive focus on intramural and other physical activity programs so that progress can be tracked on the nature and extent of these efforts.

Walking and Biking-to-School Programs

The level of progress made in increasing the number of students who walk or bike to and from school is difficult to assess. Comparisons of the 2006 SHPPS and SHP surveys with prior results may indicate the extent to which schools are more or less actively engaged in walking and biking

programs, than they were in prior years. As discussed in Chapter 6, specific programs that have focused on improving sidewalks and crosswalks, or in providing supervision for active transport to school, have resulted in greater student participation. For example, in Marin County, California, the Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program included mapping efforts, promotional activities and contests, classroom education, and organized “walking school buses” and bike trains. Comparisons of the rates of walking and biking among students between fall 2000 and spring 2002 found a 64 percent increase in the number of students who walked to and from school and a 114 percent increase in the number of students cycling to school among students in the participating schools (Staunton et al., 2003). Community-school partnerships and other efforts to enhance programs that promote active transport to and from school are greatly needed.

Research efforts continue to explore the community, safety, built environment (e.g., intersection design, crosswalks), and other factors that relate to the success of active transport programs and initiatives (Boarnet et al., 2005; Carver et al., 2005; Sisson et al., 2006; Timperio et al., 2006). Efforts to evaluate these programs are under way in many areas (FHWA/DOT, 2006) (Chapter 2). The distances to school and traffic-related danger have been the most commonly reported barriers to children walking to and from school (Martin and Carlson, 2005). The National SRTS Clearinghouse promises to be a useful resource in disseminating information on evaluations of these programs (SRTS, 2006).

After-School Programs

After-school programs are increasingly being recognized as opportunities for increasing physical activity and providing fruits, vegetables, and other low-calorie and high-nutrient foods and beverages to children and youth. In addition to a number of informal programs in individual schools and community centers, several research-based approaches are being evaluated. For example, the CATCH program—which involves multiple modifications related to school food service, physical activity, and classroom curricula—piloted a CATCH Kids Club as an after-school program for elementary school students. The program underwent pilot testing in 16 after-school programs in Texas (Kelder et al., 2005) and involved an education component, in addition to snack and physical activity segments.

Similar research-based programs examining after-school opportunities include the Georgia FitKid Project, which involves third graders in an after-school program (Yin et al., 2005a,b); the Sports, Play, and Active Recreation for Kids (SPARK) After-School program (SPARK, 2006), and the Students and Parents Actively Involved in Being Fit After-School program, which works with African-American students and parents at urban middle

schools in Michigan (Engels et al., 2005). As discussed in Chapter 6, the Girls Health Enrichment Multisite Studies (GEMS) funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) have examined pilot studies of after-school obesity prevention programs targeting African-American girls (Klesges et al., 2004, Robinson et al., 2003; Story et al., 2003) (Chapter 3), and subsequent full-scale trials are underway in Memphis, Tennessee, and Oakland, California.

As noted in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), after-school programs can be either school- or community-based and may vary widely in their content. Although the infrastructure for after-school programs is limited nationwide, organizations such as the Afterschool Alliance and the National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks are focused on obesity prevention in children and youth and are working to include nutrition and physical activity guidelines for after-school programs into school wellness policies (Afterschool Alliance, 2006).

Use of Schools as Community Centers

A recent statewide survey of West Virginia schools found that 80.7 percent of schools permitted public access to outdoor physical activity facilities and 42.3 percent provided student and community access to indoor facilities beyond the usual school hours (O’Hara Tompkins et al., 2004). Similarly, a survey of schools in specific regions of four states (Maryland, Minneapolis, Mississippi, and North Carolina) found that of the 313 schools with outdoor physical activity facilities, 240 (77 percent) allowed some public use of the facilities. Among the 210 schools with indoor facilities, 134 (64 percent) permitted some public use (Evenson and McGinn, 2004). The reasons for not opening the school facilities to the public included supervision and personnel requirements, safety concerns, and insurance and liability issues. The benefits of permitting the public use of school facilities included positive publicity for the school and keeping children physically active.

Beyond individual surveys, surveillance of the extent of community use of school physical activity facilities is conducted through the SHP and the SHPPS surveys. Efforts in some communities to combine school and community needs often include a focus on the use of school athletic facilities and other space for sports, for activity classes, and as recreation centers (Box 7-6).

Evaluating Progress to Increase Physical Activity in Schools

As discussed earlier, several national surveillance systems examine the nature and the extent of physical activity opportunities in schools (Box 7-7).

|

BOX 7-6 Schools as Community Centers Los Angeles County is examining the potential to use state school construction funds to create incentives for urban school districts and municipalities to jointly build mixed-use projects that co-locate schools with parks, libraries, health facilities, and other parts of the public infrastructure. Mixed-use concepts aim to meet both school and community needs such as having gymnasiums and play fields double as community parks and recreation centers. By utilizing school property after regular class hours and incorporating centralized libraries, health clinics and other community services, community access and engagement is increased. The state health department is also supporting these joint-use efforts, for example, by funding university research on legislative policies that the state might adopt to provide limited liability protection for the individuals and the organizations that provide space and facilities for physical activity opportunities. SOURCE: NSBN (2002). |

Several of these surveys (e.g., SHPPS, SHP) are collecting data in 2006 that will provide informative comparisons with data from prior years (Table 7-1). The 2006 SHPPS survey has a broad range of questions to assess students’ physical activity at the state, district, school, and classroom levels. The resulting data are aggregated at the national and state levels and state report cards are categorized by whether the state requires or recommends various aspects of physical education (CDC, 2006d). Furthermore, the SHP study examines several aspects of physical activity with a focus on physical education requirements. SHP results are available in a format that compares individual states and cities with other participating states and cities (CDC, 2006e).

State- and district-level surveys are also valuable for the assessment of the progress that has been made. For example, West Virginia adapted some of the 2000 SHPPS survey questions for a statewide survey of opportunities for physical activity. Questions were also added to assess community recreation opportunities and walking safety (O’Hara Tompkins et al., 2004). Individual schools can track their progress in developing opportunities for physical activity through self-assessment tools such as the School Health Index. Possible enhancements of the SHI could include a greater emphasis on intramural physical activity opportunities. Tools such as CDC’s Physical Education Curriculum Analysis Tool provide valuable technical assistance in evaluating physical activity-related curricula (CDC, 2006c).

Tracking the physical fitness progress of individual students is also an important evaluation measure. The tracking tools that schools use include

|

BOX 7-7 Examples of Survey Questions on Increasing Physical Activity Levels in Schools 2006 SHPPS School District Questionnaire (CDC, 2006h)

2005 YRBSS (CDC, 2006f)

SHP 2006 School Principal Questionnaire (CDC, 2006g)

SHI for Middle and High Schools (CDC, 2005)

|

the Fitnessgram/Activitygram® and the President’s Challenge (President’s Challenge, 2006). Both of these tools compare a student’s performance on a set of physical fitness tests with fitness standards specific to the student’s age and gender. The President’s Challenge also offers a health fitness test, an active lifestyle program, and the Presidential Champion’s program. As discussed below, there is wide variation in the extent and the manner in which schools report the student’s physical fitness results to parents and caregivers.

A number of states have awards programs for students, school personnel, schools, and school districts that have demonstrated progress in increasing physical fitness or physical activity levels. For example, in Michigan the Governor’s Council on Physical Fitness, Health, and Sports and the Michigan Fitness Foundation recognize school districts and teachers that provide high-quality physical education (Michigan Governor’s Council on Physical Fitness, Health, and Sports, 2006). The Virginia Department of Education (2006) offers a physical activity award program to school personnel (Virginia Department of Education, 2006), and Indiana offers the Governor’s Physical Fitness Award to students at all levels (Indiana Governor’s Council for Physical Activity and Sports, 2006).

Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity Curricula

Curricula aimed at improving nutrition and physical activity behaviors have been developed in research settings and are available for dissemination to schools. These curricula focus on skill-building activities and provide students with the opportunity to set goals, engage in the desired behaviors, self-monitor their efforts, and receive feedback, as well as provide incentives and reinforcement of positive lifestyle changes. Examples include curricula for reducing leisure screen time for third and fourth graders (Robinson, 1999; Stanford SMART, 2006) and improving nutrition and physical activity among middle school students (Bauer et al., 2006; Gortmaker et al., 1999).

Some indicators of progress in offering health education related to physical activity and nutrition are available by comparing the 2002 and 2004 results of the SHP survey, which found an increase across states in the percentage of schools that required health education courses included information on choosing a variety of fruits and vegetables daily (from 84.6 to 89.8 percent), preparing healthy meals and snacks (from 74.0 to 82.7 percent), and aiming for a healthy weight (from 86.3 to 93.5 percent), although decreases in providing information about choosing a variety of grains daily were seen (91.5 to 86.4 percent) (Grunbaum et al., 2005). Information is limited on which to assess whether or not these courses have a behavioral skills focus instead of an educational or informational focus. The 2006 SHPPS survey may help provide data on this aspect of health curricula, as it includes questions about goal setting, decision making, self-monitoring, and other behavioral skills. Greater attention should be focused on implementing and evaluating the outcomes of behaviorally focused curricula.

School Health and Student Assessments

School health services are the focus of attention in programs such as CDC’s comprehensive school health programs. However, it is difficult to assess whether progress in involving school health services in obesity prevention efforts is being made. The committee did not find a systematic assessment of obesity prevention efforts in school health services, which indicates a need for a comprehensive evaluation. SHPPS has a section devoted to school health services with relevant questions focused on school screening for height, weight, or BMI. The upcoming results from the 2006 SHPPS may provide insight into current screening efforts.

Assessments of the weight, height, and BMI of each student are implemented in some states as an additional form of health screening, similar to screening for vision or hearing problems (Scheier, 2004). Concerns regarding BMI screening have focused on protecting the privacy of students and ensuring that, along with the screening results, information is provided to assist students and parents in determining next steps and reducing the potential negative impact of the results on students’ mental health.

Arkansas was one of the first states to actively explore and implement assessments of the weight, height, and BMI of each student in which the results are reported to parents and guardians (Ryan et al., 2006). In addition to other provisions regarding childhood obesity prevention, the Arkansas Act 1220 (enacted in 2003) mandated that parents be provided with an annual measure of their child’s BMI, along with an explanation of BMI and the health effects associated with childhood obesity. The recently completed year 2 evaluation of Arkansas Act 1220 was conducted through surveys of school principals, school district superintendents, and licensed Arkansas pediatricians, as well as telephone interviews with a randomly selected sample of families (e.g., parents and adolescents were interviewed if consent was obtained), site visits to assess the presence and content of school vending machines, and interviews with key officials (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 2006). The evaluation found that parents and adolescents were generally accepting of BMI measurements and comfortable with the confidentiality provisions. Parents had increased their awareness of the health consequences of obesity, and increased numbers of families reported changes in planning and preparation of healthier meals. Potential negative outcomes or consequences—such as teasing, use of diet pills, or skipping meals—have not detectably increased with the distribution of BMI measurements compared with those at the baseline assessments. School principals and superintendents reported that some parents expressed concerns regarding the assessments; however, approximately one-third (34 percent) of the superintendents reported that no parent had con-

tacted them about the BMI reporting issues and 75 percent had been contacted by less than 10 parents.

Other states are also assessing student BMI levels or are planning similar assessments. Illinois requires schools to measure BMIs in their first-, fifth-, and ninth-grade students, and California schools measure BMI levels in the fifth, seventh, and ninth grade (NASPE and AHA, 2006). In September 2005, the Pennsylvania Department of Health began a growth screening program that required BMIs to be determined during annual screenings in kindergarten through the fourth grade; in the 2006–2007 school year this will extend up to the eighth grade, and in 2007–2008 it will encompass all students (PANA, 2006).

Evidence gathered from the studies conducted by Arkansas and evaluations of BMI assessment programs in other states will be valuable in clarifying the impact of BMI reporting. Similar issues are being evaluated in school systems that provide the results of physical fitness testing to students and parents.

Advertising in Schools

A recent IOM report focused on food marketing to children and youth examined issues related to commercial activities in schools including product sales, direct and indirect advertising, and conducting marketing research on students (IOM, 2006b). The Health in the Balance report recommended that state and local education authorities and schools should develop, implement, and enforce school policies to create schools that are advertising-free to the greatest possible extent (IOM, 2005). The San Francisco Unified School District Board of Education was an early leader on this issue. In 1999, the board passed the Commercial-Free Schools Act that prohibited food and tobacco advertising in educational settings (Wynns and Chin, 1999). More recent attention on this issue includes the efforts by the National Association of Secondary School Principals in developing guidelines for partnerships between schools and beverage companies that address the use of logos and signage on school grounds and the visibility of company logos (NASSP, 2004). A recent survey of 20 California high schools found that nearly 65 percent of vending machine advertisements were for sweetened beverages and that 60 percent of the posters for products were for foods or beverages that were high in fat, sugar, or sodium or low in nutrients (Craypo et al., 2006). Advertising by soft drink companies is examined by the SHPPS survey. Research and evaluations are needed to assess the ongoing trends in advertising and other commercial activities in schools and to examine whether changes in the school environment with regard to advertising can be linked to improved dietary and physical activity behaviors and health outcomes of children and youth.

Evaluation of School Programs and Policies

With the numerous programs, interventions, and policy changes being implemented in schools, it is important that they be evaluated and that those found to be effective be disseminated to other schools.

As noted earlier, the SHI is a self-assessment and planning tool designed to provide schools with a systematic means of assessing progress and planning for changes. Several elementary schools in Rhode Island used the SHI to assess their physical activity and nutrition environments and to evaluate the outcomes of a school-based intervention. The outcome measures included changes in the SHI module scores from the baseline point (October 2002) to the end of the school year (June 2003) and changes in the number of relevant policies that had been developed and implemented (Pearlman et al., 2005). A study of the use of the SHI in schools in Arizona with a high predominance of Hispanic/Latino students from low-income families found that external factors were often associated with changing policies and implementing recommendations (Austin et al., 2006; Staten et al., 2005). Both studies found similar perceived barriers to implementing nutrition and physical activity changes, including pressures to focus on reading and math test scores, low staff morale, budgetary concerns, and inconsistent support from the school administrators (Pearlman et al., 2005).

A recent study by Brener and colleagues (2006) matched school and classroom-level data from the SHPPS 2000 with comparable questions in the SHI to examine the percentage of schools meeting the SHI recommendations in four areas: school health and safety policies and environment; health education; physical education and other physical activity programs; and nutrition services. The study found that most schools are addressing school health issues to some extent, but few schools are providing a comprehensive approach. For example, the analysis of elementary school responses in SHPPS found that 38.2 percent had credentialed physical education teachers, 20.2 percent had a teacher-student ratio for physical education comparable to the ratio for classroom instruction, and only 8.0 percent met the SHI levels of 150 minutes of physical education per week (Brener et al., 2006). Data set linkages of this sort are useful in providing progress assessments.

It will be important for research and evaluation efforts to assess whether process and policy outcomes, such as those included in the School Health Index, lead to associated improvements in dietary and physical activity outcomes. A 2006 initiative of CDC, in partnership with the American School Health Association and corporate sponsors, will provide small grants to schools to support physical activity- or nutrition-related activities that are part of action plans developed through the use of the SHI (CDC, 2006a).

APPLYING THE EVALUATION FRAMEWORK TO SCHOOLS

What Constitutes Progress for Schools?

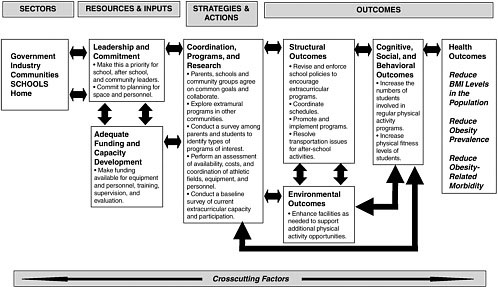

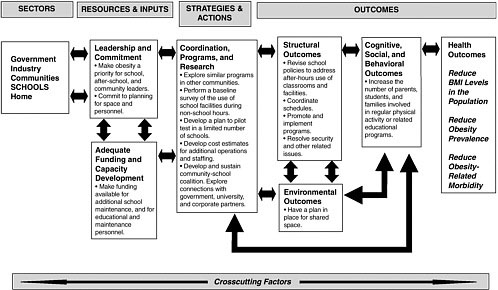

Progress resulting from changes in school-based programs and policies can be assessed through the evaluation of a range of intermediate-term and long-term outcomes. The evaluation framework introduced in Chapter 2 can be used to consider issues in evaluating school policies, programs, and other interventions. Two examples are provided: one focuses on efforts to implement after-school extracurricular physical activity opportunities and the other focuses on evaluating efforts to increase the use of schools as community centers (Figures 7-2 and 7-3). Intermediate outcomes (e.g., revising and enforcing school policies, coordinating schedules, and enhancing facilities) are important in both of these examples, as these changes are needed in order to improve access to and availability of facilities and opportunities for families and children to engage in physical activity.

Structural and systemic outcomes include the legislative and policy changes, often made by the state legislature or local school district, that pave the way for positive changes to the school environment. Examples include the implementation of school wellness policies, policies regarding comprehensive school health programs, legislative or regulatory adoption or changes in school nutrition standards, and legislative or administrative changes in physical activity requirements.

Changes in the school environment to promote more healthful behaviors are intermediate outcomes that denote increased opportunities for physical activity and healthful eating. These include increased availability of fruits and vegetables through food service choices, self-serve salad bars, or vending machines; reduced availability of high-calorie, high-sugar, and/ or high-fat foods and beverages available as à la carte items or in vending machines; increased duration, quality, and variety of physical activity classes; increased opportunities for physical activity through intramural sports and other avenues; an increased emphasis on nutrition- and physical activity-related topics in health education and other classroom curricula; and the support and promotion of walking- and biking-to-school programs.

Individual- and population-level outcomes include individual student and school population consumption of fruits, vegetables, and other low-calorie and high nutrient foods and beverages and improved physical activity testing levels and reduced sedentary behaviors. Health outcomes include reduced BMI levels in the population, reduced obesity prevalence and related morbidity, and improved child and adolescent health.

As noted throughout the report, evaluation does not need to be a complex process. Policy-monitoring efforts can report on specific state- or local-level legislative or policy changes. For individual schools and child-

care programs, outcomes could be as basic as developing and implementing a local school wellness policy; completing the needed capital improvements on sidewalks and street crossings in a community that allows children to walk and bicycle to school; increasing student awareness about the importance of healthful diets and physical activity; enhancing student knowledge about energy balance at a healthy weight; increasing the number of students who walk or bicycle to school; increasing the number of students participating in intramural programs over time; and improving the physical fitness levels of students. Specific interventions, such as a spring intramural track program, could base its evaluation on participation but could also collect baseline data on a measure of physical fitness (e.g., the time that it takes each student to run a mile) and at the end of the season assess each student’s progress. Additionally, schools can assess their overall progress toward achieving a healthy school environment by using self-assessment tools such as the SHI. Initial evaluation efforts often focus on process evaluation and then move toward linking changes in process or programs with behavioral and health outcomes (Box 7-8). The collection of baseline data is always an important first step.

NEEDS AND NEXT STEPS IN ASSESSING PROGRESS

In the midst of the numerous changes that have been made in schools to promote healthy lifestyles, the committee was encouraged by the number of resources that are currently available to monitor progress in schools at the national and the state levels. However, few of the data sets provide details at the local level. Furthermore, linkages between surveillance systems could provide needed insights into how environmental changes in schools are

|

BOX 7-8 Examples of Outcome Measures for Schools, Preschools, and Child-Care and After-School Programs

SOURCES: Boyle et al. (2004); Connecticut State Department of Education (2006). |

affecting food and beverage choices, physical activity levels, or other relevant behavioral changes. Evaluating a range of outcomes of school-based programs and interventions appears to be occurring only on a limited basis, at least in part because of the lack of emphasis on evaluation and limited time and resources.

Although the committee could explore only a small subset of the ongoing efforts by states, localities, school districts, and schools in implementing and evaluating obesity prevention policies and interventions, it is apparent that throughout the country there are wide differences in the resources available, the level of evaluation activity, and the extent of commitment to improving the school environment to promote healthy lifestyles. Some schools have implemented extensive changes, with wellness policies in place and improvements occurring in the foods and beverages they offer, the relevant curricula that they present, and the opportunities for physical activity that they provide. Other schools have not yet made changes or are focused on only one aspect of the school environment. Often, the first area of change is in the food and beverage choices made available to students.

The committee urges continued efforts to promote a healthy school environment that encompasses a breadth of changes relevant to nutrition and physical activity and extensive evaluation, as suggested in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005). Additionally, emphasis must be placed on evaluating nutrition and physical activity in child-care, after-school, and preschool settings.

Each of the committee’s four recommendations is directly relevant to improving the efforts to evaluate school-based interventions, policies, and initiatives. The following section highlights the specific implementation actions needed.

Promote Leadership and Collaboration

Given the multiple competing priorities that schools are asked to address—priorities that cover an array of academic, social, and health concerns—there has been a tendency until recently to pay less attention to efforts related to nutrition and physical activity. Leadership is needed at the federal, state, school district, and school levels to:

-

recognize childhood obesity as a serious health concern;

-

implement and prioritize the changes needed to improve nutrition and increase physical activity;

-

establish the expectation and the tracking mechanisms to ensure that standards are followed; and

-

foster creativity and student and parent involvement in developing,

-

refining, implementing, and evaluating policies, programs, and other interventions relevant to childhood obesity prevention.

Federal and state leadership is needed in providing adequate and sustained resources to implement changes relevant to obesity prevention in the school environment. Not only are political will and leadership needed to improve school nutrition and physical activity opportunities, but it is critically important that adequate and sustained funding be provided to reinforce these priorities so that attention to this issue does not result in unfunded mandates.

Develop, Sustain, and Support Evaluation Capacity and Implementation

Evaluation is vital to schools, school districts, localities, and states in determining if their initiatives are producing an impact and are effectively using the limited available resources. Currently, the evidence base on the effectiveness of school-based policy change and interventions is quite slim (Katz et al., 2005). Despite its central importance, however, limited resources to date have been devoted to evaluation efforts. As the committee heard at its Wichita symposium (Appendix F), many schools and school officials acknowledge the need for evaluations but often report that they do not have the skills, expertise, time, personnel, or financial resources to implement evaluation efforts.

One of the critical areas needing technical support and focused attention is evaluation of the effectiveness of individual programs and interventions. Individual teachers, schools, school districts, preschools, and after-school and child care programs are implementing innovative changes that need to be assessed. It is also desirable to evaluate the obesity prevention-related policies, programs, and practices of individual schools. These evaluation efforts will need to range from rigorous randomized controlled trials to determine the specific outcomes of specific interventions for specific populations to observational assessments of the associations between outcomes at all levels and the policies and practices in single classrooms, single schools, or groups of schools.

In order to initiate evaluation efforts, the committee recommends that funding be made available through CDC, USDA, and other federal agencies to provide technical assistance support through the development and dissemination of evaluation materials; the expansion of opportunities for evaluation-related training; and increases in the numbers of technical assistance personnel who are available to assist with evaluation efforts in states, localities, and school districts. Furthermore, the evaluation of obesity-prevention efforts should be made a priority and a necessary component of school-based interventions. Partnerships between schools and school dis-

tricts and their neighboring universities, colleges, public health departments, foundations and other public and private agencies and entities that have the requisite experience and skills in developing and conducting evaluations need to be developed and encouraged.

Enhance Surveillance, Monitoring, and Research

Expand and Fully Utilize Current Surveillance Systems and Tools

One of the strengths for assessing progress in obesity prevention in the school setting is the range of surveillance and assessment tools that have been developed and implemented in recent years. Because of the interest in collecting data from and about the school setting, it may be easier to assess progress in the school setting than for most, if not all, of the other relevant settings. However, despite the availability of data, gaps remain in the age groups surveyed, the depth and nature of the questions asked and the information collected, the size and representativeness of the samples surveyed, and the ability to retrieve data on a specific state or city. Furthermore, it is difficult to link changes in individual behaviors with changes in the school environment and the availability of data does not guarantee that appropriate feedback will be communicated to policy makers, schools and individuals or that the changes that result are guided by the evidence. Enhancements to current surveillance systems are needed to increase the utility of the information to policy makers and decision makers, and those who work with the students on a daily basis. A number of improvements are under way or should be implemented.

CDC is developing and testing a new component of the YRBSS that will focus on physical activity and nutrition and plans to administer it in 2010. The committee supports this effort to collect more extensive information on students’ dietary and physical activity behaviors and hopes that this survey will be conducted by a number of states at the middle school and perhaps upper elementary school levels.

Innovations in monitoring changes in the school foodservice environment also deserve additional emphasis. The third School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study (SNDA) is currently being conducted and analyzed by USDA. Previous SNDA studies were conducted in the 1991–1992 and 1998–1999 school years and provide comparative data. Efforts are needed by USDA and other agencies and organizations to further monitor and assess changes in food and beverage purchases and consumption. Innovative evaluation strategies should be explored. Marketing data and some limited data on the foods and beverages that students consume in schools are available. Strategies and mechanisms need to be in place to allow local-

level monitoring of the outcomes related to changes in the foods and beverages made available to students on sales and consumption.

SHPPS is conducted only every six years so short-term incremental changes in policies and practices are difficult to detect. Even every 6 years, however, the fact that this survey is repeated periodically with consistency in its methods and content makes it one of the most promising sources for assessing progress over time. The committee feels that the SHPPS data appear to have been underutilized. Increased analysis and dissemination of the SHPPS results and trends are needed. Given the numerous changes implemented by states and school districts, SHPPS is a vital resource for tracking progress and identifying areas needing refined interventions. Ideally, SHPPS (or separate modules of SHPPS) could be administered and the data could be aggregated at a more local level to allow progress to be tracked in schools in large metropolitan areas (as is done for the School Health Profiles study) or in other school districts that could potentially help fund the data collection and analysis. The timeliness of the 2006 SHPPS data collection, given the recent interest in improving the school environment, will provide an opportunity for analyses of the accomplishments that have been made and of the ongoing gaps and needs for further improvement.

Implement a National Survey Focused on Physical Activity

School-based efforts often focus on changing food and beverage availability, but less attention is devoted to physical activity. More needs to be learned about progress in increasing the physical activity levels and fitness of the nation’s students. The last comprehensive evaluation of this issue was in the late 1980s through the first National Children and Youth Fitness Study (NCYFS I) (1984), the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports School Population Fitness Survey (1985), and a second NCYFS (1987) (Brandt and McGinnis, 1985; Pate and Ross, 1987). An ongoing survey of physical activity levels and physical fitness—spanning from children and youth, preschool through adolescence—should be explored and should be conducted, either as a stand-alone survey or as a component of a current national surveillance system such as NHANES that has sustained long-term funding to track the progress of a representative sample of children and youth.

Support Research

Current measures for measuring the physical activity levels of children and youth are often cumbersome or intrusive. Pilot studies for the expanded YRBSS focused on physical activity and nutrition could provide opportunities for exploring various approaches to measurement. Similarly,

research on more accurate methods of measuring the dietary intake of children and youth is needed (IOM, 2006b). Measures, such as 24-hour food intake logs, are subject to the inconsistencies and other challenges of self-reported data, and other measures, such as assessing plate waste, are difficult and time consuming to obtain.

Expand and Adapt Self-Assessment Tools for Schools, Preschools, Child-Care, and After-School Programs

The SHI is a potentially useful tool that could serve as a model for similar types of self-assessment tools for preschools, after-school programs, or child-care programs. Although these settings are often independent and frequently decentralized in the manner in which they are administered, it would be valuable to develop a health index for each of these settings and encourage the dissemination of the self-assessment tools through relevant professional associations and organizations. It will also be important to assess whether performance on these tools predicts subsequent improvements in nutrition and physical activity behaviors and health outcomes.

Link Data Sets

Opportunities for linking data sets also need to be explored to allow geographic and school-level matching of policy and program outcomes with behavioral and health outcomes. The linking of these data sets has the potential to allow tracking of these associations over time. If the systematic use of the SHI could be linked with assessments of the school environment and student health behaviors and health status, such as through the YRBSS, schools could obtain substantial guidance on implementing the most promising policy-related strategies for the prevention of obesity.

Disseminate and Use Evaluation Results

The added value of an emphasis on surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation is in the lessons learned and the evidence gained from assessments of whether specific interventions and policies have a positive impact on improving nutrition, increasing physical activity, and reducing childhood obesity. As discussed in Chapter 2, there is much to be learned from those efforts that are both effective and ineffective in achieving the desired intermediate and long-term outcomes. Successful efforts need to be replicated, scaled up, and evaluated to be further refined. Unsuccessful efforts should be substantially changed and reevaluated or discontinued. In either case, the dissemination of evaluation results is crucial.

The lessons learned need to be disseminated through the traditional

mechanisms, such as through presentations at professional meetings and the publication of findings in professional journals. They also, however, need to be disseminated through innovative mechanisms that can provide teachers, principals, school administrators, and food service personnel with examples of specific interventions that can be implemented. Sharing the innovative changes through publications with concrete examples and details, such as the recent compilation by CDC and USDA of innovations in school food and beverages, Making It Happen: School Nutrition Success Stories, should be continued. Such publications should provide as much detail on the intervention and on the results of its evaluation as possible.