2

Framework for Evaluating Progress

The nation is in the midst of initiating changes in policies and actions that are intended to combat the childhood obesity epidemic across many sectors, including government, relevant private-sector industries, communities, schools, work sites, families, and the health care sector. Active evaluation of these efforts is needed. The Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005) noted that

As childhood obesity is a serious public health problem calling for immediate reductions in obesity prevalence and in its health and social consequences, the committee strongly believed that actions should be based on the best available evidence—as opposed to waiting for the best possible evidence (p. 111).

The challenge presented in this report is to take the next step toward developing a robust evidence base of effective obesity prevention interventions and practices. Evaluation is central to identifying and disseminating effective initiatives—whether they are national or local programs or large-scale or small-scale efforts. Once effective interventions are identified, they can be replicated or adapted to specific contexts1 and circumstances, scaled up, and widely disseminated (IOM, 2005).

This chapter discusses the challenges and opportunities for evaluating childhood obesity prevention efforts. Key questions and principles designed to direct and guide evaluation efforts are presented. Furthermore, the com-

mittee introduces an evaluation framework that can be used by multiple stakeholders to identify the necessary resources and inputs, strategies and actions, and range of outcomes that are important for assessing progress toward childhood obesity prevention. Subsequent chapters provide specific examples to illustrate the use of the framework in conducting program evaluations in a variety of settings. The chapter concludes with the committee’s recommendations that establish the foundation for the implementation actions discussed in subsequent chapters of the report.

OVERVIEW OF EVALUATION

Evaluation is an important component of public health interventions because it helps decision makers make informed judgments about the effectiveness, progress, or impact of a planned program. The committee defines evaluation as the systematic assessment of the quality and effectiveness of a policy,2 program,3 initiative, or other action to prevent childhood obesity. It is an effort to determine whether and how an intervention meets its intended goals and outcomes. Evaluations produce information or evidence that can be used to improve a policy, a program, or an initiative in its original setting; refine those that need restructuring and adaptation to different contexts; and revamp or discontinue those found to be ineffective. Evaluation fosters collective learning, supports accountability, reduces uncertainty, guides improvements and innovations in policies and programs, may stimulate advocacy, and helps to leverage change in society.

Many types of evaluations can contribute to the knowledge base by identifying promising practices and helping to establish causal relationships between interventions and various types of indicators and outcomes. Evaluations can also enhance understanding of the intrinsic quality of the intervention and of the critical context in which factors can moderate4 or mediate5 the interventions’ effect in particular ways. Evaluations are needed to demonstrate how well different indicators predict short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term outcomes. An indicator (or set of indicators) helps provide an understanding of the current effect of an intervention, future

|

2 |

Policy is used to refer to a written plan or a stated course of action taken by government, businesses, communities, or institutions that is intended to influence and guide present and future decisions. |

|

3 |

Program is used to refer to what is being evaluated and is defined as “an integrated set of planned strategies and activities that support clearly stated goals and objectives that lead to desirable changes and improvements in the well-being of people, institutions, environments, or all of these factors.” See the glossary in Appendix B for additional definitions. |

|

4 |

A moderator is a variable that changes the impact of one variable on another. |

|

5 |

A mediator is the mechanism by which one variable affects another variable. |

prospects from the use of the intervention, and how far the intervention is from achieving a goal or an objective. Indicators are used to assess whether progress has been made toward achieving specific outcomes. An outcome is the extent of change in targeted policies, institutions, environments, knowledge, attitudes, values, dietary and physical activity behaviors, and other conditions between the baseline measurement and measurements at subsequent points over time.

Evaluations can range in scope and complexity from comparisons of pre- and postintervention counts of the number of individuals participating in a program to methodologically sophisticated evaluations with comparison groups and research designs. All types of evaluations can make an important contribution to the evidence used as the basis on which policies, programs, and interventions are designed. A major purpose of this Institute of Medicine (IOM) report is to encourage and demonstrate the value for conducting an evaluation of all childhood obesity prevention interventions. The committee strongly encourages stakeholders responsible for childhood obesity prevention policies, programs, and initiatives to view evaluation as an essential component of the program planning and implementation process rather than as an optional activity. If something is considered valuable enough to invest the time, energy, and resources of a group or organization, then it is also worthy of the investment necessary to carefully document the success of the effort. The committee emphasizes the need for a collective commitment to evaluation by those responsible for funding, planning, implementing, and monitoring obesity prevention efforts.

Evaluation is the critical step in the identification of both successful and ineffective policies and interventions, thus allowing resources to be invested in the most effective manner. Because sufficient outcomes data are not yet available in most cases to evaluate the efficacy, effectiveness, sustainability, scaling up, and systemwide sustainability of policy and programmatic interventions, the committee uses the term promising practices in this report to refer to efforts that are likely to reduce childhood obesity and that have been reasonably well evaluated but that lack sufficient evidence to directly link the effort with reducing the incidence or prevalence of childhood obesity and related comorbidities. They are not characterized as best practices, as they have not yet been fully evaluated. Furthermore, the term best practices has inherent limitations in the conceptualization and application to health promotion and health behavior research. Green (2001) suggests that clinical interventions are typically implemented in settings with a great deal of control over the dose, context, and circumstances. The expectation that health promotion research will produce interventions that can be identified as best practices in the same way that medical research has done with efficacy trials should be replaced with the concept of best practices for the most appropriate interventions for the setting and population. Thus, best

practices resulting from health promotion research focus on effective processes for implementing action and achieving positive change. These may include effective ways of engaging communities; assessing the needs and circumstances of communities and populations; assessing resources and planning programs; or connecting needs, resources, and circumstances with appropriate interventions (Green, 2001).

As described throughout this report, childhood obesity prevention efforts involve a variety of different interventions and policy changes occurring in multiple settings (e.g., in the home, school, community, and media). This “portfolio approach” to health promotion planning may be compared with financial investments in a diversified portfolio of short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term investments with different levels of risk and reward. This type of approach encourages the classification of obesity prevention interventions on the basis of their estimated population impact and the level of promise or evidence-based certainty around these estimates (Gill et al., 2005; Swinburn et al., 2005).

Evaluations are conducted for multiple stakeholders and the findings are broadly shared and disseminated (Guba and Lincoln, 1989). These audiences include policy makers, funders, and other elected and appointed decision makers; program developers and administrators; program managers and staff; and program participants, their families, and communities. Moreover, these diverse evaluation audiences tend to value evaluations for different reasons (Greene, 2000) (Table 2-1). Evaluations inform decision-

TABLE 2-1 Purposes of Evaluation for Different Audiences

|

Purpose |

Audience |

|

Inform decision-making and provide accountability |

Policy makers, funders, and other elected and appointed decision makers |

|

Understand how a program or policy worked as implemented in particular contexts and the relative contribution of each component to improve the intervention for replication, expansion, or dissemination or to advance scientific knowledge |

Program developers, researchers, and administrators |

|

Improve the program, enhance the daily program operations, or contribute to the development of the organization |

Program managers and staff |

|

Promote social justice and equity in the program |

Program participants, their families, and communities |

|

SOURCE: Greene (2000). |

|

making, provide accountability for policy formulation and reassessment, and enhance understanding of the effectiveness of a program or policy change. Evaluations are also used to improve or enhance programs and promote the principles of social justice and equity in the program. Encouraging the dissemination of the evaluation results to a broad audience is an important element of developing a “policy-shaping community” that serves as a critical constituency for further implementation and evaluation efforts (Cronbach and Associates, 1980).

Evaluation should also be conducted with appropriate respect for diverse cultural practices, traditions, values, and beliefs (Pyramid Communications, 2003; Thompson-Robinson et al., 2004; WHO, 1998). As discussed further below and in Chapter 3, it is important to be particularly attentive to existing health and economic disparities in conducting evaluations of childhood obesity prevention actions and programs as reflected in the type of evaluation questions asked and the criteria used to make judgments about program quality and effectiveness.

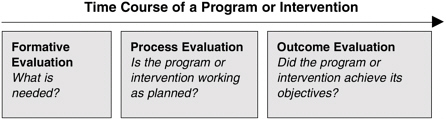

Different types of evaluations (e.g., formative, process, and outcome evaluations) (Box 2-1) relevant to the stage of the intervention and the purpose of the evaluation are conducted. In addition, impact evaluation may be conducted to examine effects that extend beyond specific health outcomes and may include economic savings and benefits, cost-utility, and improved quality of life (CGD, 2006).

Large-scale interventions often build on multiple evaluations from the outset of the project so that at each step along the development and implementation of the project, data are collected and analyzed to assess the best use of resources and to make refinements as needed.

Evaluations provide data that are interpreted to generate judgments about the quality and the impact of the program experience for its participants and about the planned and desirable outcomes that have been achieved. These judgments often rest on established standards and criteria about educational quality and nutritional, dietary, or physical activity requirements, among other criteria. Too often an evaluation is focused on a narrow set of objectives or criteria and the broader policy or program goals may not be adequately considered. Additionally, stakeholders may vary in their judgments about how much improvement is sufficient for a program to be viewed as high quality and effective (Shadish, 2006). A comprehensive review of childhood obesity prevention interventions examined a variety of selection criteria for interventions including methodological quality, outcome measures, robustness in generalizability, and adherence to the principles of population health (e.g., assessments of the upstream determinants of health, multiple levels of intervention, multiple areas of action, and the use of participatory approaches). Of 13,000 programs that promote a healthy weight in children and that were recently reviewed, only 500 pro-

vided adequate information about their implementation that could be used to identify promising practices for childhood obesity prevention based on chosen criteria (Flynn et al., 2006).

The committee has identified several relevant criteria that can be used to judge the design and quality of interventions and encourages funders and program planners to consider the following actions:

-

Include diverse perspectives (House and Howe, 1999) and attend to the subpopulations in the greatest need of prevention actions—particularly underserved, low-income, and high-risk populations that experience health disparities;

-

The use of relevant empirical evidence related to the specific context when an intervention is designed and implemented;

-

The development of connections of program efforts with the efforts of similar or potentially synergistic programs, including a concerted effort to develop cross-sectoral connections and sustained collaborations; and

-

The linkage of interventions that aim to produce structural, environmental, and behavioral changes in individuals and populations relevant to childhood obesity prevention.

The committee developed six overriding principles to guide the approach to program evaluation. First, evaluations of all types—no matter the scale or the level of complexity—can contribute to a better understanding of effective actions and strategies. Localized and small-scale obesity prevention efforts can be considered pilot projects, and their evaluation can be modest in scope. Second, defensible and useful evaluations require adequate and sustained resources and should be a required component of budget allocations for obesity prevention efforts—for both small local projects and large extensive projects. The scope and scale of evaluation efforts should be appropriately matched to the obesity prevention action. Third, evaluation is valuable in all sectors of obesity prevention actions. It is important to recognize that effective action for obesity prevention will not be achieved by a single intervention. However, an intervention or a set of interventions that produces a modest or preliminary change may contribute importantly to a larger program or effort. Multisectoral evaluations that assess the combined power of multiple actions can be especially valuable for informing what might work in other settings. Fourth, evaluation is valuable at all phases of childhood obesity prevention actions, including program development, program implementation, and assessment of a wide range of outcomes. In particular, evaluation can contribute to an improved understanding of the effects of different types of strategies and actions—leadership actions, augmented economic and human resources, partnerships, and coalitions—on the short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term outcomes. Fifth, useful evaluations are contextually relevant, are culturally responsive, and make use of the full repertoire of methodologies and methods (Chapter 3). Evaluations may need to be modified, depending on how programs evolve, the evidence collected, and shifts in stakeholder interests. Sixth, evaluation should be a fundamental component of meaningful and effective social change achieved by stakeholders engaging in a range of dissemination and information-sharing activities through diverse communications channels to promote the use and scaling up of effective policies and interventions. Because evaluation offers opportunities for collective learning and accountability, widespread dissemination of evaluation findings

can lead to policy refinements, program improvements, community advocacy, and the strategic redirection of investments in human and financial resources.

EVALUATION CAPACITY

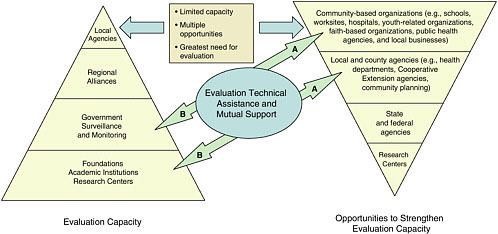

Insights obtained during the committee’s three regional symposia suggest that there is a substantial gap between the opportunity for state and local agencies and organizations to implement obesity prevention activities and programs and their capacity to evaluate them (Figure 2-1). It was not surprising to find that at the community level, where the great majority of obesity prevention strategies are expected to be carried out, the capacity for conducting comprehensive program evaluations is limited. Research conducted in academic settings is the principal source of in-depth scientific evidence for specific intervention strategies. Existing public sector surveillance systems and special surveys serve as critical components for the ongoing monitoring and tracking of a wide range of childhood obesity-related indicators. Although more comprehensive evaluations are needed and surveillance systems need to be expanded or enhanced, especially for the monitoring of policy, system, and environmental changes, the gap between the opportunity for evaluations and the capacity to conduct evaluations at the local level appears to be a significant impediment to the identification and widespread adoption of effective childhood obesity prevention programs.

Three strategies might be helpful in addressing the opportunity-capacity evaluation gap. First, and most important, local program managers should be encouraged to conduct for every activity and program an evaluation that is of a reasonable scale and that is commensurate with the existing local resources. The evaluation should be sufficient to determine whether the program was implemented as intended and to what extent the expected changes actually occurred. For most programs for which strategies and desired outcomes are adequately described, careful assessment of how well those strategies are carried out (also called fidelity) and modest assessments of outcomes after the program is implemented compared with the situation at the baseline are sufficient. In these contexts, obtaining baseline measures at the outset of programs is critical. As noted above, every program deserves an evaluation but not every intervention program needs to or has the capacity to undertake a full-scale and comprehensive evaluation. Second, government and academic centers can increase the amount of guidance and technical assistance concerning intervention evaluations that they provide to local agencies (Chapter 4). Third, government and academic agencies and centers conducting comprehensive evaluations can more quickly identify activities and programs that deserve more

extensive evaluation if they communicate frequently with local agencies and each other about their interventions.

The two-way arrows highlighted in Figure 2-1 symbolize the dual benefit that is likely to result when the academic and governmental sectors partner with local programs to enhance evaluation capacity at the local level. The arrow tips marked “A” connote the delivery of local-level evaluation capacity building through the planned efforts of the academic and the governmental sectors. The arrow tips marked “B” reflect the opportunities for those in the academic and governmental sectors to work with and expand upon local pilot programs that show promise for attaining measurable health benefits and merit consideration for diffusion and replication.

Although it may be unrealistic to expect local-level program personnel to have the capacity to conduct full-scale comprehensive evaluations, it is not at all unreasonable for local-level programs to have in place practical mechanisms that will enable them to detect, record, and report on reasonable indicators of the progress and the impact of a program. Issues and examples related to who will pay for the evaluation efforts and the role of government and foundations are discussed throughout the report.

Training opportunities to enhance the ability of stakeholders to conduct evaluations are needed. As indicated above, evaluation is often viewed as primarily being within the purview of foundations, government, and academic institutions. Evaluation is a basic function and integral element of public health programs. However, the core competencies related to conducting community evaluations should be widely disseminated to staff members of nonprofit organizations, schools, preschools, after-school programs, faith-based organizations, child-care programs, and many others. The full utilization of the expertise of academic institutions, foundations, and public health departments in partnership with community and school groups will provide the knowledge base for well-designed evaluation strategies. Tools such as distance learning can take further advantage of disseminating this information. As discussed in Chapter 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases is focused on state capacity building, implementation, and enhanced training opportunities. Several practitioner-focused training programs have been developed through the CDC Prevention Research Centers (Chapters 4 and 6). Further, evaluation training for teachers and school staff can be included as a component of school wellness plans and will provide another opportunity to enhance evaluation capacity.

EVALUATION FRAMEWORK

Children and youth live in environments that are substantially different from those of a few decades ago. Many environmental factors substantially

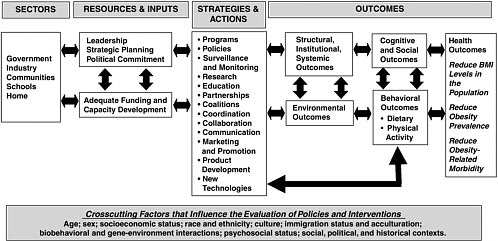

increase their risk for obesity. Efforts to evaluate obesity prevention programs should take into account the interconnected factors that shape the fabric of the daily lives of children and youth. Experienced evaluators have long acknowledged the importance of identifying and understanding the key contextual factors (e.g., the environmental, cultural, normative, and behavioral factors) that influence the potential impact of an intervention (Tucker et al., 2006). The evaluation framework that the committee developed offers a depiction of the resources, strategies and actions, and outcomes that are important to childhood obesity prevention. All are amenable to documentation, measurement, and evaluation (Figure 2-2). The evaluation framework also illustrates the range of important inputs and outcomes while giving careful consideration to the following factors:

-

The interconnections and quality of interactions within and among the multiple sectors involved in childhood obesity prevention initiatives;

-

The adequacy of support and resources for policies and programs;

-

The contextual appropriateness, relevance, and potential power of the planned policy, intervention, or action;

-

The relevance of multiple levels and types of outcomes (e.g., structural, institutional, systemic, environmental, and behavioral for individuals and the population and health outcomes);

-

The potential impact of interventions on adverse or unanticipated outcomes, such as stigmatization or eating disorders (Doak et al., 2006); and

-

The indicators used to assess progress made toward each outcome; selection of the best indicators will depend on the purpose for which they are intended (Habicht and Pelletier, 1990; Hancock et al., 1999) and the resources available to program staff to collect, analyze, and interpret relevant data.

CDC has developed three guides for evaluating public health and other programs relevant to obesity prevention, including: Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health (CDC, 1999), Introduction to Program Evaluation for Public Health Programs (CDC, 2005a), and Physical Activity Evaluation Handbook (DHHS, 2002). The guides offer six steps for evaluating programs: (1) engage stakeholders, (2) describe the plan or program, (3) focus the evaluation design, (4) gather credible evidence, (5) justify conclusions, and (6) share lessons learned. Other important elements for program development and evaluation emphasized by the guides include the documentation of alliances, partnerships, and collaborations with those in other sectors; the establishment of program goals and objectives; the assessment of the available human and economic resources; and the selection of specific

intervention strategies that are appropriate for different settings and contexts. In addition to these evaluation steps, the framework described in this chapter: (1) encourages the evaluation of a range of outcomes—structural, institutional, systemic, environmental, cognitive, social, behavioral and health; (2) emphasizes the importance of crosscutting factors that influence the evaluation of policies and interventions; and (3) further elaborates the committee’s ideas about relevant criteria for judging the design and quality of interventions. These features are discussed in the next section.

Components of the Evaluation Framework

Actions that prevent childhood obesity are expected to proceed through stages similar to those for other public health interventions. Progress in this field depends on consistent and sustained action as indicated in the left-to-right flow across the columns of the evaluation framework (Figure 2-2). The interchange and feedback that will nurture and contribute to this effort are indicated by the double-headed arrows throughout the framework diagram. Once a problem is identified, strategies are formulated to obtain funding and develop institutional and community capacity to address the problem. In some circumstances, the process begins when committed leaders seek to strengthen human and economic resources in multiple sectors through which a variety of actions and programmatic efforts will be implemented. Strategies and actions are tailored to address the known determinants and precursors of the health problem. From the outset, efforts are made to ensure that systems are in place to evaluate the process and generate the information used to inform midcourse corrections in the intervention and ascertain the extent to which important outcomes are achieved. Evaluation should also provide a better understanding of the problem and meaningful, effective, and sustainable ways to address it.

Sectors

The first column in the framework delineates the specific sectors in which childhood obesity prevention actions can be undertaken and evaluated—government, industry, communities, schools, and home. Sub-sectors are covered under the main sectors; for example, media is discussed under the industry sector (Chapter 5), foundations and health care are discussed under the communities sector (Chapter 6), and child-care and after-school are discussed under the school sector (Chapter 7). The activities of these sectors are interdependent; and prevention actions will have a higher likelihood of success when the public-sector, private-sector, and voluntary or nonprofit organizations purposefully combine their respective resources,

strengths, and comparative advantages to ensure a coordinated effort over the long term.

Resources and Inputs

Key resources and inputs include leadership, political commitment, and strategic planning that elevate childhood obesity prevention to a high priority. Adequate and sustained funding through government appropriations and philanthropic funding and capacity development are needed to initiate and sustain effective obesity prevention efforts. Evaluation of these two sets of factors can provide information about the adequacy of the leadership and the resources committed to a specific childhood obesity prevention initiative (Chapter 4). An essential implication of this framework is that rhetoric is an inadequate response. Announcements or statements made by leaders in all sectors should be accompanied by resource allocation and policy and programmatic actions committed to reversing the childhood obesity epidemic. Evidence of planning and adequate resource allocation and appropriations by government leaders, philanthropic boards, senior corporate managers, and shareholders is needed.

At the national level, an example of both resource allocation and leadership is the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, a joint initiative of the William J. Clinton Foundation and the American Heart Association, which established the Healthy Schools Program6 in 2006 with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The purpose of this program is to foster healthy environments that support efforts to reduce obesity in school-aged children and youth (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2006a). In May 2006, the Alliance announced a new initiative in collaboration with industry representatives—including Cadbury Schweppes, The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, and the major trade association that represents these companies, the American Beverage Association—to establish new guidelines to limit portion sizes; prohibit the sale of sweetened beverages and high-calorie, low-nutrient foods; and offer calorie-controlled servings of beverages to children and adolescents in the school environment. This is the Alliance’s first industry agreement as part of the Healthy Schools Program and has the potential to affect an estimated 35 million students across the nation (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2006b) (Chapters 5 and 7).

From the outset of this effort, the Alliance stated two measurable objectives that can be used as outcome indicators to assess the program’s

progress: companies will work to implement changes to promote the availability of healthful beverages and foods in 75 percent of the public and private schools that they serve before the start of the 2008–2009 school year and in all U.S. schools by 2010 (Alliance for a Healthier Generation, 2006b) (Chapter 5). These objectives are both quantifiable and measurable, thus making it feasible to track progress.

However, the complexity of evaluating multiple ongoing initiatives is acknowledged. In contexts such as these, in which local programs are implemented while a larger-scale nationwide intervention is occurring, there may be parallel and reinforcing activities that present challenges in assessing the relative contribution of each intervention. A systems approach to health promotion and childhood obesity prevention offers the opportunity to develop and evaluate interventions in the context of the multiple ongoing efforts (Green and Glasgow, 2006; Midgley, 2006). However, evaluation methods of this approach are currently not well developed (Best et al., 2003) and further research is needed in this area. Methodological work in the evaluation of systemic initiatives in public education may offer some good starting points (for example, Ruiz-Primo et al., 2002).

Nevertheless, national leadership and support should be acknowledged and documented as a strategy that can support and reinforce the goals of local efforts.

Another example of leadership and resource allocation is the Healthy Carolinians Microgrants program. The program provided small support grants to each of 199 communities in North Carolina (up to $2,010) to increase local awareness of the objectives described in Healthy People 2010, mobilize resources, and create new partnerships in community health improvement (Bobbitt-Cooke, 2005).

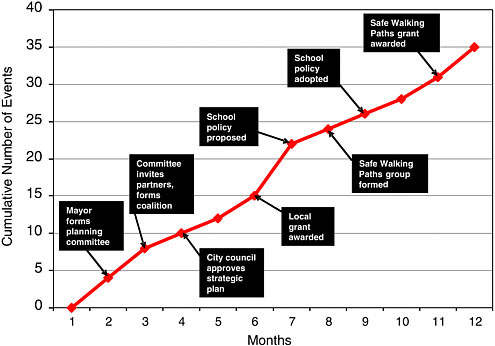

Fawcett and colleagues (1995) have created a simple procedure that assists local program evaluators in documenting changes in programs, policies, and practices that are stimulated in part by organized community-based prevention strategies. The ability to document these events, the methods of which are accessible online (Fawcett et al., 2002), enables evaluators to share the relevant short-term indicators and outcomes of a program’s progress while awaiting the long-term population health outcomes. Once the relevant events and accomplishments are documented, they can be plotted on a timeline to demonstrate the progress of the overall effort. It should be noted, however, that these events related to the observed changes in communities are associative rather than causative (Figure 2-3).

Strategies and Actions

As depicted in Figure 2-2, a variety of strategies and actions are needed to effectively use the resources and inputs for childhood obesity prevention

FIGURE 2-3 Hypothetical trends in the rate of community and system changes (e.g., the implementation of new programs and policies) stimulated by obesity prevention efforts during the first year.

(e.g., leadership, political commitment, funding, and capacity development) to produce positive outcomes. Strategies are the concerted plans for action that when implemented through changes such as new product development or the enactment of legislation on nutritional standards for school foods and beverages result in outcomes that can be assessed. Evaluating the extent to which strategies are being developed (e.g., state action plans, federal agency coordination) and implemented through actions (e.g., enactment of new legislation, marketing of new products) is a necessary step in determining the extent of progress in childhood obesity prevention. The interactions among complex social, economic, and cultural factors, combined with the varying availability of resources, require that interventions should be adapted to meet the particular needs, circumstances, or contexts of a community or setting. In the absence of generalizable solutions, effective planned childhood obesity prevention efforts will consist of a variety of potential strategies and actions based on an assessment of local needs, assets, conditions, and available resources. On the basis of the results of these assessments, obesity prevention program planners can draw from an array of

strategies and actions, as depicted in the evaluation framework (Figure 2-2). All elements of the framework are amenable to evaluation.

The Kansas Coordinated School Health Program illustrates how several key strategies and actions (e.g., programs, coalition, collaboration, and coordination)7 can be used in combination to promote health outcomes for school-aged children and youth (Kansas State Department of Education, 2004). Through a grant awarded by the Kansas Coordinated School Health Program, the Goddard School District (which is located in West Wichita, Sedgwick County, and which includes three elementary schools, one intermediate school, two middle schools, and one high school) offered health promotion activities and resources (Kansas State Department of Education, 2004; Greg Kalina, Coordinator of the Goddard School District Nutrition Program, personal communication, April 24, 2006) with the dual goal of benefiting both students and school staff:

-

A mapped walking course on elementary school playgrounds and inside school hallways;

-

Monday morning stretch exercises led by trained teachers on closed-circuit television at the intermediate school;

-

The provision of pedometers and walk-run and marathon events for students, faculty, staff, and community residents;

-

Nutritious snack options at staff and district committee meetings and the introduction of low-calorie and high nutrient snack options in schools;

-

Two annual teacher in-service programs on healthful nutrition choices and physical fitness;

-

A fitness center for staff, established with equipment donated by staff members and expanded with locally raised funds; and

-

Training for staff on the proper use of the fitness center equipment.

Both formative and process evaluations can assist with the assessment of the quality of the strategies and actions used at an early phase of the implementation of interventions. These types of evaluations can reveal in-

sights at three levels: (1) the strength of the underlying rationale for the program as a vehicle for addressing childhood obesity, (2) the ways in which the program is well matched to specific settings, and (3) the ways and extent to which program implementation is being carried out in accordance with expected standards and the program is working as planned. The results attained through process evaluation not only will provide information that enables program planners to make needed adjustments in the program during its formative stages but also will yield critical insights about the intervention after outcomes data are available. In the Kansas initiative described above, process evaluation data could include records of children and staff who use the fitness center and walking course and the proportion of students and staff participating in the stretching exercises, as well as findings from teacher and student surveys assessing the perceptions of the value of these additions to the school district’s facilities.

An example from West Virginia illustrates how attention to strategies and actions (the third column of the evaluation framework in Figure 2-2) provides support to local-level obesity prevention program activities. The Partnership for a Healthy West Virginia consists of representatives from education, health care, nonprofit and faith-based organizations, business, and state government who developed a 3-year statewide action plan to address obesity. One key component of the action plan was to provide policy recommendations to the West Virginia governor and legislature. The proposal was strategically built on previously successful education and advocacy efforts under the leadership and organizational credibility of the West Virginia Action for Healthy Kids Team, the West Virginia State Medical Association, and the American Heart Association. Two key policy recommendations were proposed: (1) enhance and increase the amount of physical education in all public schools and (2) limit access to sweetened carbonated soft drinks and high-calorie foods and meals in public schools while offering increased access to foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet. On the basis of the efforts of this state coalition, the governor introduced and supported the Healthy West Virginia Act of 2005. Both policy recommendations (policy implementation is a structural outcome in the fourth column of the evaluation framework) have been included in the new law (HWVA, 2005).

The challenge of tracking the implementation of the policies is being addressed by one of the partners, the State Department of Education. The Department’s Office of Child Nutrition has the responsibility for monitoring compliance with the competitive food sales policy which includes monitoring the sale of sweetened soft drinks and the availability of foods with low nutritional value at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. The Office of Healthy Schools has the responsibility for tracking three key areas: (1) fitness testing using the FITNESSGRAM®/

ACTIVITYGRAM®8; (2) representative sampling of the body mass index (BMI) levels of students; and (3) adherence to State Board of Education standards for specified hours that students must engage in physical activity at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. Through a legislative mandate, the Office of Healthy Schools also operates a statewide, online health education assessment system called the Health Education Assessment Project. This system annually reaches 65,000 students from selected grade levels and assesses a wide range of student health knowledge, including knowledge of the need for physical activity and good nutrition. West Virginia school officials use the results of this assessment to identify knowledge gaps and make curriculum recommendations.

The California Teen Eating, Exercise, and Nutrition Survey (CalTEENS) (Box 2-2) is an example of intersectoral collaboration among a variety of stakeholders in the government, education, and industry sectors to promote childhood obesity prevention strategies. CalTEENS is a comprehensive biennial survey conducted in 1998, 2000, and 2002, of the eating and physical activity behaviors of more than 2 million of California’s adolescents ages 12 to 17 years (Public Health Institute, 2004).

Both the Partnership for a Healthy West Virginia and CalTEENS benefit from participation by a broad range of partner organization and agencies. Furthermore, obesity prevention activities are often consistent with the goals of a wide range of other health initiatives, including those concerned with supporting chronic disease prevention, school health, work site health promotion, and urban planning strategies such as Smart Growth.

Outcomes

The evaluation outcomes selected will depend on the nature of the intervention; the timeline of the program or intervention; and the resources available to program implementers and evaluators to collect, analyze, and interpret outcomes data. The timeline of the intervention often necessitates whether the evaluation can assess progress toward a short-term outcome (e.g., increasing participation in an after-school intramural sports team), an intermediate-term outcome (e.g., changes to the built environment that promote regular physical activity for children and youth), or a long-term outcome (e.g., a reduction in BMI levels of children participating in a new program). Outcomes can also be categorized on the basis of the nature of the change (Figure 2-2):

|

BOX 2-2 Organizations Supporting CalTEENS

|

-

Structural, institutional, and systemic outcomes;

-

Environmental outcomes;

-

Population or individual-level cognitive and social outcomes;

-

Behavioral outcomes (e.g., dietary and physical activity behaviors); and

-

Health outcomes.

Examples of the range of outcomes across different sectors are summarized in Table 2-2. The committee emphasizes the need to develop programs and interventions that can effect changes in all types of outcomes.

Structural, institutional, systemic, and environmental factors can significantly influence access to and the availability of healthful choices and behaviors. Neither children and youth nor their parents can choose to eat fruits and vegetables unless these are available, affordable, and culturally acceptable in their own communities and in the settings where they spend time. Children and youth cannot choose to spend their after-school time engaged in physical activities if they do not have safe spaces to engage in those activities or places to play. Nor will they increase their in-school physical activity in the absence of school policies that mandate and monitor requirements that children and youth engage in a specified level of physical activity each school day or week. These structural and environmental factors both constrain and enable individual and family choices about food and physical activity.

The federal government launched the Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program in 2005 to address some of these issues. The SRTS program assists communities around the nation with making walking and bicycling to school a safe and routine activity for children and youth. The program provides funding to states to administer a variety of initiatives,

TABLE 2-2 Examples of Outcomes in the Evaluation Framework

|

Outcome |

Examples |

|

Structural, institutional, and systemic outcomesa |

|

|

Environmental outcomesb |

|

|

Cognitive and social outcomesc |

|

|

Outcome |

Examples |

|

|

|

|

Behavioral outcomesd dietary and physical activity outcomes |

|

|

Health outcomese |

|

|

aStructural outcomes represent the development, implementation, or revision of policies, laws, and resources affecting the dietary patterns and physical activity behaviors of children, youth, and their families. Institutional outcomes are changes in organizational cultures, norms, policies, and procedures related to dietary patterns and physical activity behaviors. Systemic outcomes are changes in the way that eating and physical activity environments and health systems are organized and delivered. bEnvironmental outcomes are changes that create a health-promoting environment, including access to low-calorie and high nutrient foods and beverages and opportunities for regular physical activity. cCognitive outcomes are changes in an individual’s knowledge, awareness, beliefs, and attitudes about the importance of healthful diets and regular physical activity to reduce the risk of obesity and related chronic diseases. Social outcomes are changes in social attitudes and norms related to dietary and physical activity behaviors that support healthy lifestyles. dBehavioral outcomes are changes made by individuals or populations that affect their diet and physical activity levels and enhance health. eHealth outcomes are changes made by individuals or populations that either reduce or increase their risk of developing specific health conditions. |

|

from building safer street crossings to establishing programs that encourage children and their parents to walk and bicycle safely to school (FHWA/ DOT, 2006). The Marin County, California, SRTS program, for example, is focused on reducing local automobile congestion around schools while promoting students’ healthy and sustainable habits. The program includes several components that have proven to be effective, including classroom education, special events, and incentives that encourage children and adolescents to choose alternative forms of transportation to schools, as well as technical assistance to identify and remove the barriers to walking, bicycling, carpooling, or taking transit to school. Evaluations of the SRTS program have demonstrated that making environmental changes can lead to increases in children’s physical activity patterns (Parisi Associates, 2002; Staunton et al., 2003) (Chapters 4 and 7). The California Department of Health Services has replicated the SRTS program in other cities, which has led to outcomes such as community audits of street, sidewalk, and bikeway conditions; the improved mobility of pedestrians and bicyclists; reduced speed and volume of motor vehicles; and improved motor vehicle compliance with traffic laws (Parisi Associates, 2002). Results linking the SRTS program to health outcomes for children and youth have not yet been reported.

Behavioral outcomes are the population and individual mediators of behavior (e.g., awareness, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values, preferences, and skills) and actual behavioral and social changes that affect dietary patterns and physical activity, and thus, energy balance. These outcomes not only are important at the individual level (such as outcomes desired by a pediatrician, nurse, or teacher when he or she is counseling a child or adolescent and his or her parents about healthy dietary practices and physical activity) but also apply on a population level to those implementing large-scale campaigns or programs targeting communities, states, or regions. An outcome of concern has been the potential for stigmatization of children and youth who are obese. Ongoing efforts are examining stigmatization as well as normalization of obesity (i.e., larger sizes and portions becoming the accepted norm).

Behavioral outcomes include changes in dietary patterns and physical activity for children and adolescents to achieve energy balance at a healthy weight. Planet Health is an example of an efficacious school-based intervention designed to reduce BMI levels and obesity prevalence in a multiethnic group of middle-school-aged children in an affluent setting. The program provided evidence that a well-planned and well-evaluated intervention aimed at reducing television viewing time, increasing physical activity, and improving nutrition behaviors can make a difference in reducing obesity prevalence in girls (Gortmaker et al., 1999). It is one of the few

childhood obesity prevention interventions that has conducted a cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness evaluation. The results of this evaluation found that the Planet Health program is likely to be cost-effective as it is currently implemented (Wang et al., 2003).

The end outcomes relate to promoting health—increasing the number of children and adolescents who are at a healthy weight, reducing the BMI levels in the population, reducing the number and prevalence of children and youth who are obese or at risk for obesity, and reducing the risks for obesity-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (Chapter 3). These are the ultimate outcomes, but their achievement may require years of effort with sustained resources and societal change.

Crosscutting Factors

Certain programs, policies, strategies, or actions may be effective for some groups but not others. A variety of crosscutting factors influence program experiences and thus the evaluation process and will need to be considered at every stage of the evaluation framework for both individuals and populations. These include age, sex, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, culture, immigration status, acculturation, biobehavioral and gene-environment interactions, and psychosocial status, as well as social, political, and historical contexts. Context refers to the set of factors or circumstances that surround a situation or event and give meaning to its interpretation. All of these factors should be taken into account when obesity prevention initiatives are designed, monitored, and evaluated, as depicted in Figure 2-2 (Hopson, 2003) (Chapter 3).

A useful example of the important roles that are played by some of these crosscutting factors (e.g., age, sex, and race/ethnicity) can be drawn from the VERB™ social marketing campaign. The goal of the VERB campaign was to encourage more than 21 million multiethnic American tweens (i.e., ages 9 to 13 years) to become more physically active. (See Chapter 4 for a detailed description of the VERB campaign.) Before CDC launched the 5-year, VERB—It’s what you do. campaign in 2002, it conducted a formative evaluation that used marketing research techniques to gain insights into a variety of relevant factors to assist in understanding how physical activity levels can be increased and maintained in the targeted age group. The formative research showed that tweens would respond positively to messages that promoted moderate physical activity in a socially inclusive environment and that emphasized self-efficacy, self-esteem, and belonging to their peer group (Potter et al., 2004).

Key Evaluation Questions and Approaches

Changing stakeholder perceptions about evaluation—from a daunting task of questionable value to a manageable and highly useful endeavor that informs future efforts—can be facilitated by considering four key evaluation questions to guide childhood obesity prevention policies and interventions. Although these questions are relevant to obesity prevention actions, strategies, and programs across all sectors, not every evaluation can be expected to address all of the questions.

The relevance of the four evaluation questions (Box 2-3) depends on the type of the obesity prevention action, policy, or program and the available evaluation capacity (e.g., resources and technical expertise). The majority of childhood obesity prevention interventions are implemented at the local level, where the resources, time, opportunities, skills, and capacity for conducting an evaluation are often limited compared with those available to academic institutions and state or federal governmental agencies. Although some of the evaluation capacity gap can be filled through collaborative partnerships between local agencies and academic institutions, a large portion of locally implemented interventions will occur with no opportunity for conducting a full-scale evaluation. Yet all promising childhood obesity prevention interventions deserve some level of evaluation. Small-scale, grassroots, and exploratory efforts can be evaluated inexpensively and modestly, and if deemed appropriate, subjected to a more sophisticated evaluation at a later stage.

CDC and RWJF are in an early stage of collaborating on a process called the Pre-Assessment of Community-Based Obesity Prevention Interventions Project to identify promising interventions that meet certain ob-

|

BOX 2-3 Questions to Guide Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies and Interventions

|

jective and minimum criteria to consider programs for an in-depth and rigorous evaluation of their effectiveness. The process is expected to be transparent and guided by expert peer reviewers. This evaluability assessment process would allow the selection of programs that are likely to produce the greatest magnitude of impact for the financial investment. The most promising initiatives would be presented to potential funders for more extensive evaluation funding (Laura Kettel-Khan, CDC, personal communication, May 27, 2006).

Evaluation involves multiple methodological approaches, all of which should be used to reach the goal of reducing and preventing childhood obesity. Various evaluation methods are likely to be relevant to each of the four questions as discussed below.

Question 1. How does the action contribute to preventing childhood obesity? What are the rationale and the supporting evidence for this particular action as a viable obesity prevention strategy, particularly in a specific context? How well is the planned action or intervention matched to the specific setting or population being served?

These are descriptive questions about the nature and extent of childhood obesity challenges and the responses in the relevant contexts and are likely to be well addressed by three sets of methods:

-

Review of the existing literature and databases (e.g., the demographic, nutrition and dietary intake, physical activity, health promotion, urban planning and community design, transportation, social science, anthropology, food and beverage marketing, and entertainment literature databases) can serve to extract pertinent information about the nature and the extent of the childhood obesity epidemic in the settings and contexts to be served and may perhaps allow longitudinal monitoring of the epidemic.

-

Use various methods to focus on specific characteristics of the settings and contexts to be served such as consumer focus groups, key informant interviews, community-based participatory research, needs assessments, and asset mapping (Goldman and Schmalz, 2005; Green and Mercer, 2001; Kretzmann and McKnight, 1993).

-

Encourage networking to identify and describe the other childhood obesity prevention actions underway in these settings and contexts.

Question 2. What are the quality and reach or power of the action as designed?

This question calls for an in-depth description of the planned action,

with special attention to its underlying logic and rationale, and for an assessment of its quality and viability as an approach to obesity prevention among children and youth in the settings and contexts being served. For example, are the objectives aligned with the recommendations for population-level change?

Two sets of parallel methods are likely to be relevant for this question:

-

Qualitative methods may be useful for developing a sound and comprehensive description of the planned action, intervention, or program. These include document review and text analysis (e.g., of program or policy proposals, legislative initiatives, or media campaigns). Individual and group interviews with program planners, administrators, and implementers are also useful for the identification of critical components of and rationales for the intervention, program, or policy being planned.

-

The quality of the theory or logic and rationale for the proposed intervention, program, or action can then be assessed by turning to relevant literature and to experts, as well as practitioners in the contexts being served. These assessments call for qualitative methods such as document review, interviews, and concept mapping, and can be supplemented by policy analysis.

Question 3. How well is the action carried out? What are the quality and reach or power of the action as implemented?

These implementation questions are far-reaching and their answers require the use of a variety of methods in combination. Evaluating the implementation of programs is often called process evaluation. A process evaluation is defined as the means of assessing strategies and actions to reveal insights about the extent to which implementation is being carried out with regard to expected standards, the “dose” of the intervention received, and the extent to which a given action or strategy is working as planned. For example, quantitative data on the level of program participation or the depth of the reach to target populations (e.g., changes in knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs) may be determined from administrative or program records or may be assessed by surveys. Observations and interviews—both structured (quantitative) and unstructured (qualitative)—can play a useful role in gathering data and evidence about the program’s implementation and effectiveness. These data offer windows into how the participants experienced the action or the program. Furthermore, an analysis of the media coverage of an action, program, or policy can also yield valuable information about the quality of program implementation.

Question 4. What difference did the action make in terms of increasing the availability of foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet, opportunities for physical activity, other indicators of a healthful diet and physical activity, and improving health outcomes for children and youth?

Finally, the question of the consequences and changes that resulted from the action evaluated invokes a variety of evaluation strategies. At this point, expectations about evaluation designs are appropriately scaled to the scope and size of the intervention. In most local and community-based settings, relatively modest comparisons of pre- and postintervention counts or the preintervention–postintervention results for selected outcome measures will provide sufficient information. In tandem with other information on program quality, as available, and professional judgment, these preintervention–postintervention comparisons are likely to be sufficient to determine if the intervention deserves to be continued, needs improvement, or should be rejected.

More methodologically sophisticated methods relevant to larger-scale interventions may involve:

-

A correlational methodology that seeks to establish associative relationships between participation in or exposure to an intervention and subsequent changes in structures or environments, attitudes, or behaviors;

-

A case study approach, which seeks to provide an understanding in some depth of the dynamics of change in selected contexts, with special attention to important contextual influences; and

-

Experimental and quasiexperimental methodologies that focus on establishing defensible causal relationships between an intervention, action, or program, on the one hand, and changes in structures and environmental factors or individual attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors, on the other hand.

The larger the scope and the higher the level of resources devoted to the initial intervention, the more important it is to consider the value of using more sophisticated evaluation methods at the outset. This is particularly true for interventions in which state or federal policies are involved because the entire target population is affected and, once implemented, adequate baseline measures of the preimplementation status may be impossible to obtain. The larger and more sophisticated correlational, case study, experimental or quasiexperimental evaluations should also include cost and benefit information to allow estimates of the cost-effectiveness and the cost-utility of interventions to be made (Siegel et al., 1996). Mixed-method

|

BOX 2-4 Applying the Evaluation Framework to Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions Contexts and Sectors How does the action contribute to preventing childhood obesity? What are the rationale and the supporting evidence for this particular action as a viable obesity prevention strategy, particularly in a specific context? How well is the planned action or intervention matched to the specific setting or population being served?

Resources and Inputs, Strategies, and Actions What are the quality and reach or power of the action as designed? How well is the action carried out? What are the quality and reach or power of the action as implemented?

|

evaluation designs9 can be useful for catalyzing thoughtful, creative, and innovative changes and identifying promising childhood obesity prevention interventions.

Connecting the Key Evaluation Questions to the Evaluation Framework

It is helpful to think about the components of the evaluation framework—sectors, resources and inputs, strategies and actions, and outcomes—in light of the four evaluation questions (Box 2-4). In planning an evalua-

Outcomes What difference did the action make in terms of increasing the availability of foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet, opportunities for physical activity, other indicators of a healthful diet and physical activity, and improving health outcomes for children and youth?

|

tion, consideration should be given to the fact that the relevance of each set of evaluation questions will depend on the scope and maturity of the action or program undertaken. A new or modest initiative may be best evaluated by concentrating on evaluative questions related to the context or the sector and to program design and implementation. A more mature initiative should be evaluated in terms of its intermediate-term or long-term outcomes (e.g., behavioral or health outcomes), contextual relevance, and the quality of the implementation. A policy may be best evaluated by focusing on structural or environmental outcomes. An educational program may be best evaluated in terms of its impact on individual- or family-level changes in knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Local or community-based actions may be able to monitor only selected indicators of knowledge or attitudinal or institutional change. Whatever the nature of the evaluation, it can make an important contribution to the overall knowledge base regarding childhood obesity prevention.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES IN EVALUATING PROGRESS FOR CHILDHOOD OBESITY PREVENTION

Several issues identified in Chapter 1 require attention in the early stages of an evaluation design. First, evaluation is often not a priority for the individuals or the organizations that are developing a new policy, program, or intervention. Second, realistic outcomes need to be selected to measure progress. It is often more realistic for programs to identify and examine short-term and intermediate-term outcomes than long-term health outcomes such as changes in BMI levels. Third, resources for evaluation are often scarce and should be optimally used and complemented with technical assistance and training. Fourth, the strengthening of collaborative efforts and the use of a systems approach to childhood obesity prevention are important and must be pursued, along with methodologies that can effectively assess the quality and effectiveness of collaborative and systemic initiatives.

Like many other public health crises, the current childhood obesity epidemic has multiple, concurrent, and interconnected causes. As articulated in the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005), these causes include the uneven distribution of low-calorie and high nutrient foods, and lack of affordable fresh fruits and vegetables in communities and schools; the easy availability and access to foods and beverages that are high in total calories, fat, saturated and trans fats, added sugars, and sodium; the marketing of products to children and youth that appeal to their tastes but that have limited nutritional value; community settings that do not naturally support and encourage children and youth to be physically active; school policies that do not support or enforce the requirements for adequate time for physical activity; and social norms that reinforce both a sedentary lifestyle and the consumption of high-calorie processed foods and beverages. These problems are related to the distribution, access, and costs of healthful diets and the availability of safe places for children to play. They are present throughout the nation but may have the most detrimental impact and reverberations in low-income and resource-constrained communities (Chapter 3). The complexity of the childhood obesity epidemic poses several challenges for the prevention effort and the evaluation approach that need to be acknowledged. The challenges can be grouped into issues of causation, the measurement of dietary patterns and physical activity behaviors, the development of interventions, surveillance and monitoring by use of different data sources and measurement tools, and the translation of findings to diverse settings and populations.

Attributing Causation and Effects to Interventions

Because of the numerous and intertwined determinants of changes in dietary intake and physical activity it is often difficult for a single intervention, especially if it is modest in scope, to have a measurable impact (Swinburn et al., 2005). In addition, the impact of targeted programmatic interventions is difficult to determine when other often broader population-level interventions, such as media campaigns or increases in opportunities for physical activity in the community, are going on at the same time. The effectiveness of targeted programmatic interventions may also be obscured by gaps or barriers elsewhere in the chain. For example, classroom instruction on the value of physical activity, even if it is effective, may be irrelevant to children or youth who do not have safe places to be active outside or who are more strongly attracted to new sedentary pursuits, such as watching television shows, playing sedentary DVDs and videogames, or using the Internet. Furthermore, behavioral improvements resulting from an intervention in one setting may be offset by compensation or regression in other settings. For example, an increase in activity level during a physical education class may be counterbalanced by a change in after-school activities that increase the time that a child or adolescent spends in sedentary activities, such as more recreational screen time. Similarly, reducing calorie intake with a more nutritious lunch purchased in the school cafeteria may be offset by the increased consumption of high-calorie snacks after school. Finally, interventions addressing systemic and environmental precursors of childhood obesity and other factors early in the causal chain cannot be expected to demonstrate changes in the prevalence of childhood obesity in the short term.

The difficulties inherent in assessing the contribution, if any, of a single intervention, plus the multiplicity of interventions currently being implemented at the individual, family, community, state, and national levels, elevate the need for summary evaluation methods. Thus, in addition to evaluations of specific policies and programs, there is a need for population-wide assessment that examines the overall progress of the prevention of childhood obesity. Surveillance and monitoring will provide the data needed for these types of assessments.

Measuring Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity Behaviors

Current methods of measuring dietary patterns and activity behaviors are insufficiently precise to accurately detect subtle changes in energy balance that can influence body weight (IOM, 2005, 2006; NRC, 2005). The difficulties lie in measuring the energy involved in a specific exposure (e.g., the number of calories consumed at lunch or expended in physical educa-

tion class) and the full range of places, times, and ways in which energy expenditure occurs (e.g., at home or school, during or after school, or during free time or scheduled activities). All currently available measures of dietary and physical activity behaviors capture only a portion of daily behaviors and do so, at best, with only modest accuracy. Similar problems exist for the measurement of the determinants of excess energy consumption or insufficient energy expenditure. For example, accurate methods of measuring access to fruits, vegetables, and other low-calorie high nutrient foods and beverages or places for engaging in physical activity are still being developed. In addition, the specific characteristics of the built environment that are instrumental in making foods and beverages that contribute to a healthful diet accessible or that encourage play and physical activity on a regular basis are not known. Therefore, the evaluation tools, indicators, or performance measures10 that are available may lack sufficient specificity (e.g., precision) or sensitivity (e.g., ability to measure incremental change at appropriate levels) to relate specific behaviors to specific outcomes. The task of evaluation will be greatly facilitated by research on and the development of more accurate measurement tools, indicators, and performance measures.

CDC is in an early phase of developing the Obesity Prevention Indicators Project, which will identify and select potential indicators and performance measures for the evaluation of obesity prevention programs and interventions. This process proposes to provide a forum for the sharing of information among funding agencies about current and future strategies and initiatives on program funding, monitoring, and evaluation; the development of criteria for the identification and the selection of common indicators that can be shared across national-, state-, and community-level programs; and the summary and dissemination of selected indicators for program evaluation by intervention setting and also according to recommendations presented in Healthy People 2010 and the Health in the Balance report (IOM, 2005) (Laura Kettel-Khan, CDC, personal communication, May 27, 2006).

Developing Interventions

Interventions pertaining to the structural and systemic causes of childhood obesity, such as those focused on overcoming the paucity of public parks and playgrounds in high-risk neighborhoods or providing easy access

to fresh fruits and vegetables, are recognized as important contributors to the prevention of childhood obesity. However, there is limited empirical evidence to guide their development or their evaluation. Innovative approaches to evaluation design that measure the relative impact of multiple changes to the built environment on a population’s behaviors are needed, for example, methods that assess the collective impact of designing sidewalks, walking trails, and public parks on physical activity levels (TRB and IOM, 2005). Analyses of the contribution of community change to population health outcomes that have been conducted in other areas of public health, such as automobile and highway safety, may offer insight into methods that can be used to assess the contribution of environmental changes (e.g., amount, intensity, duration, and level of exposure) to long-term population-level outcomes. Modifications of highways, intersections, and pedestrian crossings, in conjunction with changes in the use of seatbelts, child safety seats, and other interventions have been extensively evaluated (Economos et al., 2001; NTSB, 2005).

Translating and Transferring Findings to Diverse Settings and Populations

The social and cultural diversity within the United States precludes assumptions about the transferability of interventions from one subsector of the population to another. A program that succeeds in Oakland, California, may not do well in Birmingham, Alabama. This does not mean that interventions are not transferable, because despite the cultural and racial/ethnic diversity of the U.S. population, we share many common characteristics. However, it means that transferability is not assured and should be assessed. As new information is generated, it will be important to ensure that the new information and evidence is promptly incorporated into ongoing interventions (Chapter 3). Table 2-3 describes three main areas—knowledge generation, knowledge exchange, and knowledge uptake—and 12 in-

TABLE 2-3 Three Areas and 12 Components of Evidence-Based Policymaking

|

Knowledge Generation |

Knowledge Exchange |

Knowledge Uptake |

|

Credible design |

Relevant content |

Accessible information |

|

Accurate data |

Appropriate translation |

Readable message |

|

Sound analysis |

Timely dissemination |

Motivated user |

|

Comprehensive synthesis |

Modulated release |

Rewarding outcome |

|

SOURCE: Choi (2005). |

||

terdependent elements of evidence-based policymaking (Choi, 2005). The knowledge generation, exchange, and uptake sequence can be used to generate, translate, and transfer or adapt the results of obesity prevention research and program evaluations to present promising practices to different target audiences.

Surveillance and Monitoring: Data Sources and Measurement Tools

Surveillance and monitoring activities generally do not provide an adequate evaluation of any single intervention effort. They do, however, provide an essential assessment of the progress of the overall effort to the prevention of childhood obesity. Current surveillance systems are primarily designed to monitor the health and behavioral components of the obesity epidemic. Surveillance systems that monitor the precursors of changes in dietary and physical activity behaviors, such as policy change or alterations in the built environment, need to be expanded or developed.

A variety of surveillance systems are useful sources of data. Several types of measurement tools can be used to monitor and evaluate childhood obesity prevention policies and interventions. Appendix C provides a detailed summary of many available data sources and outcome indicators that may be used to assess progress by use of the evaluation framework for different sectors. A brief summary is provided below.

Several organizations monitor policies as well as proposed or enacted state legislation related to obesity prevention (Appendix C; Chapters 4 and 7). Examples include the CDC’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Legislative Database (CDC, 2005b), the National Conference of State Legislatures’ summary of childhood obesity policy options (NCSL, 2006), the Trust for America’s Health annual report of federal and state policies and legislation (TFAH, 2004, 2005), and NetScan’s Health Policy Tracking Service for state legislation on school nutrition and physical activity (NetScan, 2005). However, there is great variability within and across these legislative databases. The committee noted that a central database or information repository that tracks obesity-related legislation and that can be periodically updated is needed.

Several national and state cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys provide indicators and outcomes related to childhood obesity prevention surveillance and monitoring (Appendixes C and D). Different types of proprietary data sources could potentially be informative for the monitoring and evaluation of childhood obesity prevention policies and interventions. However, because proprietary data are collected for commercial purposes by private companies, either the data are not publicly available or the cost of obtaining the data is prohibitively expensive (IOM, 2006). Nevertheless, marketing research data about children and adolescents, trends in the mar-

keting of consumer food and beverage products, and food retailer supermarket scanner point-of-sale data (IOM, 2006; NRC and IOM, 2004) (Chapter 5) can be purchased from marketing and media companies and analyzed, and the results can be published in peer-reviewed publications. Moreover, because marketing data become less commercially useful over time, older data may be donated for public use purposes.

A comprehensive inventory of the available databases and measurement tools is beyond the scope of this study. However, programs may use different tools in various settings to obtain results about indicators and outcomes. These include the BMI report card and the FITNESSGRAM®/ACTIVITYGRAM® used in the school setting (Chapter 7); health impact assessments used for environmental changes (Chapter 6); mobilizing action through community planning and partnerships (Chapter 6); and a system dynamics simulation modeling (Homer and Hirsch, 2006). This type of modeling can be used to understand a variety of factors—obesity trends in the United States, the types of interventions needed to alter obesity trends, the subpopulations that should be targeted by specific interventions, and the length of time needed for actions to generate effects (Laura Kettel-Khan, CDC, personal communication, May 27, 2006).

Support Needed from Research and Surveillance

The evaluation framework presented in this report is offered in direct support of the U.S. childhood obesity prevention efforts. As obesity prevention programs, strategies, and actions continue to be initiated around the country, evaluation can play a critical role in furthering our collective understanding of the complex character and contours of the obesity problem and of meaningful and effective ways to address it. The committee emphasizes that program evaluations of varying scope and size at all levels and within all sectors have a vital role to play in addressing the childhood obesity epidemic. Evaluation can help to document progress, advance accountability, and marshal the national will to ensure good health for all of our children and youth.

In support of this commitment to evaluation, targeted research is also needed to

-