–6–

Residence Principles for the Decennial Census

CHANGE DOES NOT COME EASILY to the decennial census; it is too large and intricate an operation for massive overhauls of operations or procedures to be feasible in a short amount of time. The quality of the resultant data is paramount, and so implementing procedures that have not been tested is inadvisable. A discussant at the 1986 Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics (COPAFS) conference on residence rules noted similar comments on the nature of change in the census in one of the presented papers and wondered if the statement was mildly euphemistic, whether “this is perhaps another way of saying that we are unlikely to do much to make any needed improvements in time for the 1990 census, since we are beginning to think seriously about the problem in December of 1986” (Sweet, 1987:6). Twenty years later, with the 2010 census looming in the not-too-distant future and even with the benefit of somewhat better lead time, we face something of the same problem.

In our case, there are very promising signs of improvements to the collection of residence information in 2010. The advent of the American Community Survey and, with it, the narrowing of focus on a short-form-only decennial census is a considerable simplification and has permitted earlier attention to residence considerations than in the past. As we have noted, residence concepts were a primary focus of the 2005 census test and will be the topic of a further mailout experiment in 2006. Also, as witnessed in our panel’s public meetings, the Census Bureau has made good strides in redrafting and revising both the census residence rules and the definitions of group quarters.

We conclude that the Census Bureau would be best served by some radical revamping of its basic approaches to collecting residence information. It is unrealistic to expect large-scale changes in the 2010 census. Rather, our intent in this report is to provide a mix of short-term and long-term guidance: short-term proposals that can be implemented in 2010 and long-term research topics (to be informed by tests conducted in 2010) to provide a basis for decisions in 2020 and beyond.

In this chapter we discuss the basic nature of residence rules and argue for a principle-based approach to defining residence. A core set of residence principles should be used to develop related products and operations (Section 6–A). The second half of this chapter discusses the implications for the most important such product, the census questionnaire itself and the specific residence instructions in it (Sections 6–C and 6–D). In discussing the general presentation of residence concepts to census respondents, we suggest the need for a major change in the way residence information is gathered, switching from an instruction-based to a question-based approach (6–E). In Section 6–F, we discuss a particular problem in communicating with census respondents, encouraging prompt replies to the census form while still preserving the meaning of Census Day. We close in Section 6–G with recommendations for research on presentation issues.

6–A

A CORE SET OF PRINCIPLES

As discussed throughout this report, the residence rules for the decennial census must satisfy several needs simultaneously. They have primarily been regarded as an internal Census Bureau reference, but also must be adaptable to the construction and phrasing of items on the census form and must govern the design of related census operations. They must also be a resource for the training of temporary census enumerators and a reference to census staff who must field questions from census respondents.

As we noted in Chapter 2 and Recommendation 2.1, the Census Bureau’s current approach of trying to serve all these needs with a single document is seriously flawed. The 2000 census rules were so long and intricate that it was difficult to discern their meaning; with effort, one can intuit some of the logic that guided the construction of the rules, but the task is difficult. The situation needs to be reversed: a concise core set of residence principles should be developed, and all the related products and extracts—question wording and structure, enumerator training materials, and so forth—should be built using the principles as a base.

At the 1986 COPAFS residence rules conference, Lowry (1987:30–31) made an early call for the reduction of formal census residence rules to a set of basic principles. He argued that the Bureau would be better served by hav-

ing the residence rules (for the 1990 census) “express general principles rather than merely treating the most common examples of residential ambiguity.” Specifically, he proposed six principles:

-

If respondent lived for more than half of the preceding year at an address that he occupies on [Census Day] or expects to return to in the following year, that address is his usual residence.

-

If respondent lived for more than half of the preceding year at an address that he does not expect to return to in the coming year, his usual residence is the address he now occupies or expects to occupy for most of the coming year.

-

If respondent has several homes, no one of which he occupied for more than half of last year, he should select one as his usual residence. If an editor must choose, choose the current residence.

-

If the respondent has a home to which he returns in the intervals between traveling, that home is his usual residence even though he may have been elsewhere for more than half of the preceding year.

-

If the respondent says he has no usual residence or gives no address for his usual residence, he should be enumerated as a transient at the place where he was staying when contacted.

-

If the respondent says his usual residence is elsewhere but gives an incomplete, wrong, or invalid address for that residence, he should be enumerated as a resident of the smallest geographic unit that is unambiguously codable from his response—census block, enumeration district, tract, city, county, or state.

Discussants at the workshop found these principles to be generally reasonable; the workshop summary concluded that “a system that relies on well-defined principles, yet can incorporate responses from people in a wide variety of living [situations,] should accommodate appropriate decisions about just where to count each individual as of April 1st” (CEC Associates, 1987:6).

The Lowry (1987) principles have attractive features: the third principle subtly suggests an approach of collecting data on multiple residences and putting the onus of determining the usual residence on the Census Bureau, not the respondent. The sixth principle is intriguing, with its bold approach of associating people only with large geographic areas (e.g., cities, counties, or states) if that is all that can be validated from their provided residence information; how these larger-area counts would be distributed in block-level redistricting counts is not specified and would surely be contentious. A strength of the Lowry (1987) principles is their anchoring to a reference period of 6 months, interpreting either a retrospective (first principle) or prospective (second principle) stay of the majority of a year as the basic definition of usual residence. But that specificity is also a limitation, since 6 months is a coarse time interval with respect to some living situations; the third and fourth principles weaken the hard-line 6-months criterion, imparting some ambiguity in the determination of residence.

We conclude that the census would benefit from the specification of a core set of residence principles and retain some of the desirable features of the Lowry (1987) exemplars, but take a somewhat different approach in our recommendation.

A key component of a set of residence principles for a decennial census is an indication of the general residence standard to be pursued. As we state in Section 2–F.2, we know of no pressing reason why the U.S. census should shift away from the de jure/“usual residence” approach as its basic standard (though we also believe that it is useful that this decision be periodically revisited). So, in suggesting a candidate set of residence principles, we support a system that seeks a de jure count; the de facto/current residence location should be used as a tie-breaker in cases where no usual residence can be determined.

Assuming a general de jure model, and taking as given the objective of the census as a resident count (rather than a citizen count), we recommend adoption of a set of principles based on the following:

Recommendation 6.1: Suggested Statement of Residence Principles: The fundamental purpose of the census is to count all persons whose usual residence is in the United States and its territories on Census Day.

-

All persons living in the United States, including non-U.S. citizens, should be counted at their usual residence. Usual residence is the place where they live or sleep more than any other place.

-

Determination of usual residence should be made at the level of the individual person, and not by virtue of family relationship or type of residence.

-

If a person has strong ties to more than one residence, the Census Bureau should collect that information on the census form and subsequently attempt to resolve what constitutes the “usual residence.”

-

If a usual place of residence cannot be determined, persons should be counted where they are on Census Day.

Unlike the Lowry (1987) principles, we do not specify a fixed reference period in our first principle, the basic definition of usual residence. In our deliberations, we found that the varied living situations that must be accounted for in the census do not lend themselves easily to any choice of a time window we could construct. Ultimately, we find that a definition of usual residence must necessarily be somewhat ambiguous in order to be most broadly applicable. In our first principle, we use the wording “more than any other place” rather than other language (like “most of the time”) because we favor use of a plurality rule and because we find it less ambiguous than “most of the time.”

Even so, ambiguity remains about the relevant time frame against which “more than any other place” is to be assessed; in addition, the issue of whether any element of prospective living arrangements should be considered remains unspoken (e.g., new movers, who intend to live at this location more than any other place but have not been living there for very long). Some of the ongoing research we recommend in the remainder of this chapter should be brought to bear on refining this principle—it should, for instance, consider whether including a specific reference period has a significant impact on response or respondent confusion. In the interim, our definition of usual residence strives to reduce some ambiguity but necessarily leaves some issues open.

The second principle asserts that usual residence should be viewed as an individual-level attribute, not one that is tied to family relationships or type of residence. This principle is included to be consistent with changes that we recommend in enumerating what has traditionally been treated as the group quarters population. As we argue in more detail in Chapter 7 (and as follows from descriptions of some group quarters types like health care facilities and jails—Sections 3–C and 3–D.2), the concept of group quarters enumeration requires comprehensive reexamination. The expected length of stay and actual living situations in some group quarters types is such that it is inappropriate to characterize residence status for all facility residents based solely on the facility’s name or type. Including the provision that usual residence does not depend on family relationship speaks to situations such as college students living away or children in joint custody. This is a principle that some respondents may continue to violate, given the strength of enduring ties, but we believe that it is useful to have this concept expressed as a principle rather than something to be inferred from a long list of examples.

The third principle foreshadows arguments that we will make later in this chapter. We favor an approach in which the census form asks a sufficient number of questions to get a sense of each person’s residential situation. Significantly, we believe that it is important that the census move toward collection of information on any other residence that a person may be affiliated with. Our ultimate vision is of a census in which residence information is collected without burdening respondents with the problem of deciding who is usually resident at their address; those kinds of determinations should be made by the Census Bureau during processing of the forms, based on the data provided by respondents to a series of residence questions.

Finally, the fourth principle is a “tie-breaker” rule. There are some living situations that do not lend themselves to an unequivocal determination of a place where a person lives or sleeps more than any other; examples include dedicated recreational vehicle users and children in joint custody situations who spend equal time with both parents. When a usual residence cannot be determined, the person’s location on Census Day—the de facto residence location—should be used.

Of course, these are not the only principles that could be developed for the census, but we believe them to be an adequate set. Other possibilities include something akin to Lowry’s sixth principle, which raises the question of the level of geographic resolution needed for tabulation; that principle would assign people to the smallest possible level of geography (but not necessarily to a specific geographic coordinate). We revisit the question in Chapter 7 and the counting of the group quarters/nonhousehold population. Another possible principle—perhaps useful for handling some ambiguous residence situations but that may be prohibitively difficult operationally—is to specify that children under a certain age must be counted at the home of their parent or guardian. Though it would provide an alternate solution to the current mismatch between the counting of boarding school and college students and could be more consistent with a “family” interpretation of household, the specification of the age cutoff could make enumeration of college students even more difficult.1

Collectively, our four suggested principles imply the exclusion of American citizens (nonmilitary and nongovernment employee) living overseas, consistent with practice in recent censuses. To satisfy the requirements of current law and court precedent, military personnel and federal civilian personnel stationed overseas, and their dependents, would continue to be assigned to their home states of record for purposes of apportionment only.

6–B

PRODUCTS FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PRINCIPLES

Articulation of a core set of principles provides a basis from which to work in developing other products, one of which is an explanation of how the principles apply to a variety of living situations. The 2000 census model of trying to craft rules to match all possible living situations is flawed because it lacks a unifying conceptual basis. Yet there is still a definite need for something analogous to the intent of the 31 rules—a list of examples of how ambiguous living situations should be resolved—but one that is grounded in concept and better structured for comprehension.

Such a listing is needed for several reasons and audiences. Though field enumerators should be made familiar with the basic residence principles, it is also useful for them to be aware of concrete examples of the application of the principles to living situations that they are likely to encounter. Similarly, staff who deliver questionnaire assistance by telephone should also have common situations and their treatment as a reference. We suggest in Section 2–F.2 that census residence rules be made more transparent to the public and to decisionmakers, and public posting of examples of the application of chosen

residence principles to various living situations is an important part of that effort.

A good way to meet this need would be with a “frequently asked questions” (FAQ) list, as has become common on Web sites. Residence situations and their treatment under the residence principles should be grouped thematically for easier use. Box 6-1 illustrates a possible mapping of our recommended principles to residence situations. This structure can certainly be improved—particularly for a version to be posted on the Internet—but it provides a basic starting point for development of an FAQ list and other census documents.

The location at which prisoners should be counted has become a major point of contention. Our suggested principles—and our interpretation of them, in Box 6-1—lead us to side with the Census Bureau’s current general procedure of counting them at the location of incarceration. At this time, not enough is known about the exact nature of the alternative of counting prisoners at a place other than the prison, nor about the accuracy and consistency of facility data on inmate residence, to recommend change in counting prisoners in the 2010 census. However, we strongly urge that the 2010 census include a major test on the collection of additional residence information from prisoners and further assessment of the quality of administrative records that could inform future reconsideration of the prisoner counting issue. We discuss these initiatives below and in Chapter 7.

The residence principles should also be used to generate residence-based products in addition to the FAQ list of applications. Key among these are any specific instructions or other cues included on the census questionnaire itself; we discuss this in greater detail in the balance of this chapter.

The residence principles should be thought of as an integral part of the entire census process, not a small, side component. They should be used as a template for the development of related census operations. Chapters 7 and 8 discuss three major operations—techniques for group quarters/nonhousehold enumeration, programs to update the Master Address File, and routines to unduplicate census records—that should be designed with residence principles as a guiding concept.

Other census operations for which residence principles should be kept in the forefront include:

-

development and implementation of unduplication algorithms, including any revisions to the primary selection algorithm (used to screen and combine duplicate census questionnaires) and plans for “real-time” unduplication during the census process (we discuss this briefly in Section 8–B);

-

development of the advance letter that precedes the main questionnaire mailout, including instructions for requesting a foreign language ques-

|

Box 6-1 Illustration of Application of Residence Principles as the Basis for “Frequently Asked Questions” 1. PEOPLE WITH ONLY ONE RESIDENCE Count at the location where they live or sleep more than any other place. Examples include:

2. PEOPLE WITH MORE THAN ONE RESIDENCE Collect information on “any residence elsewhere.” Count at the location where they live or sleep more than any other place. If time is equally divided between locations, count at the location where they are found on Census Day. Examples include:

3. PEOPLE WHOSE LIVING SITUATION CHANGES ON CENSUS DAY Count at the place where they live or sleep—or will live or sleep, in the case of babies— more than any other place.

4. U.S. CITIZENS LIVING OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES Count on the basis of U.S. law and court precedent. Currently, this means including the following groups in apportionment counts only; all other U.S. citizens residing overseas are not included in the count.

5. PEOPLE LIVING IN SPECIAL PLACES ON CENSUS DAY Collect information on “any residence elsewhere,” along with information on duration of stay (tailored institutional forms). Based on duration of stay, availability of residence information, and whether census record for that residence lists that person, count at the residence. If no other information is available, count at the facility. Examples include:

|

|

-

tionnaire, and any follow-up mailings (e.g., reminder cards or the proposed second/replacement questionnaire mailout);

-

refinement of the Bureau’s routines for editing census data and imputing for nonresponse;

-

development of experiments to be performed during a decennial census and of formal evaluations of census operations; and

-

design of public outreach programs.

6–C

PRESENTATION OF RESIDENCE CONCEPTS TO RESPONDENTS AND ENUMERATORS

The Census Bureau took a first step toward self-enumeration—that is, questionnaires filled out by respondents themselves—in the 1960 census. Households were mailed an “Advance Census Report” that enumerators later picked up in person and copied onto computer-readable schedules. On the strength of that experience, mailout and mailback of census questionnaires became the dominant form of census conduct in 1970, when approximately 60 percent of the nation’s housing units were mailed questionnaires. By 2000, approximately 82 percent of housing units were reached by mail.

Mail administration of the census has obvious operational efficiencies in comparison with deploying enumerators to interview every household. However, self-enumeration profoundly affects the process of a census, shifting the burden of comprehending and interpreting the meaning of questionnaire concepts from a trained enumerator to an untrained respondent. As a result, the modern census questionnaire has to satisfy several, sometimes conflicting, constraints:

-

The questionnaire (and any other material in the “package” mailed to households, such as a cover letter) must be self-contained and comprehensive enough to guide the respondent through the process of providing complete, accurate answers. (Of course, capacity should still exist for assistance by phone or on the Internet and for requests of census questionnaires in languages other than English, if necessary, but the hope of mailout/mailback techniques is collection of data from the largest number of respondents possible without any direct intervention.)

-

The questionnaire must be designed in such a way that the human reader can easily follow the flow of the questionnaire, but also so that the questionnaire can be scanned electronically for editing and tabulation.

-

The questionnaire should be visually appealing (or, at the very least, not off-putting) in order to maximize respondent interest and willingness.

-

The questionnaire cannot be unduly long in terms of the number of questions. It must satisfy U.S. Office of Management and Budget limitations on respondent burden under the Paperwork Reduction Act; in recent censuses, the length and content of the census long form has drawn particular concern.2

-

For maximum efficiency, the questionnaire must also meet physical size and shape limitations imposed by computer scanning technology. Even though the 2010 census is oriented as a short-form-only census—with the long-form content shifted to the American Community Survey—questionnaire content must also be conducive to the development of computer-assisted versions for follow-up by telephone or (in 2010) hand-held computing device.

-

Census questionnaires must be printed relatively quickly and cheaply, and in massive quantities.

-

Census questionnaires must include space for technical features, such as a block for the mailing address and Master Address File identification number or spaces for enumerators or census clerks to code operational information as needed.

Self-response questionnaires and their properties are a topic of vital research in statistics and survey methodology; indeed, the study of their properties has grown in importance with the availability of new technologies for survey administration such as automated telephone interviews and data collection through questionnaires on the Internet. Methodological work on self-

response surveys does not suggest a single “best” way to obtain residence data from respondents to the massive-scale survey that is the decennial census. In simplest terms, what modern survey methodology tells us about census questionnaire design and structure is that presentation matters.

Finding 6.1: Responses to self-administered census forms dependupon the visual layout and design of questionnaires as well as the actual wording of questions and residence cues.

The Census Bureau’s approach in recent decades has been to produce designs that try to find an elusive, optimal level of instructions and cues at the beginning of the questionnaire in order to try to get best compliance with Bureau residence standards. However, modern survey research suggests a set of basic findings on the impact of questionnaire layout and the interpretation of visual and graphical cues in survey questionnaires. These findings (based, e.g., on Christian and Dillman, 2004; Jenkins and Dillman, 1995; Redline and Dillman, 2002; Schwarz et al., 1998; Tourangeau et al., 2004; Conrad et al., 2006; Tourangeau et al., 2006) should drive the collection of residence and other information in the decennial census.

Finding 6.2: Evidence suggests that people often ignore instructions on questionnaires. In addition, they may disregard instructions with which they disagree, even if they do read them.

“Ignore” and “disregard” are admittedly strong words; respondents’ failure to read and follow instructions is not necessarily a hostile act. People may assume the questions are designed to be interpretable and, as a result, may feel that they do not need direction. People who do read the instructions may not completely understand them and, if they disagree with some points (e.g., where to count their college student child), may decline to follow them. Such assumptions and disagreements are particular problems for the basic census residence question, since people are likely to assume that they know where they live and who lives with them. They may also be impatient with lengthy instructions and scan only enough to get the gist (as they see it) of what the question is asking.

Modern survey research also supports three key ideas that should guide questionnaire design:

-

When instructions are needed, they should be placed where they are most needed.

-

When multiple instructions are needed, the most important one—or the one that is most likely to apply—should be placed first. Respondents are less likely to read an instruction the further down it is in the list.

-

Visual cues should be used to convey what respondents are supposed to do. For example, white space (against a light background color) or some other graphical feature should be used to indicate when a response is required. Other graphical cues should indicate what form the response should take (e.g., boxes invite respondents to check one or more items).

6–D

INSTRUCTIONS AND RESIDENCE QUESTIONS IN RECENT CENSUSES AND TESTS

As prologue to suggestions on how best to present residence concepts to respondents, it is instructive to consider the ways in which recent U.S. censuses have presented residence instructions and cues. We also discuss the approaches taken in census tests and follow-up census operations, as well as strategies used in foreign censuses.

6–D.1

Previous U.S. Censuses

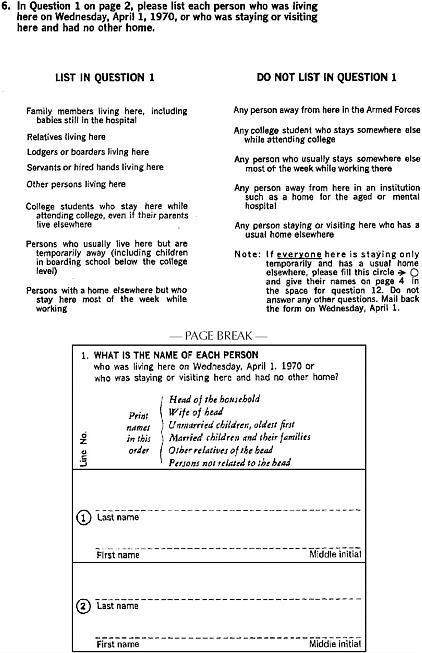

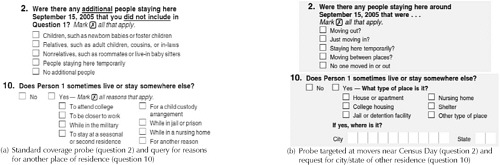

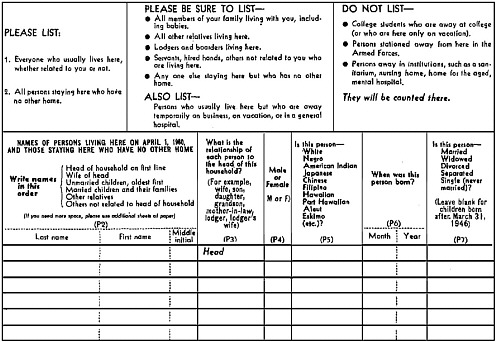

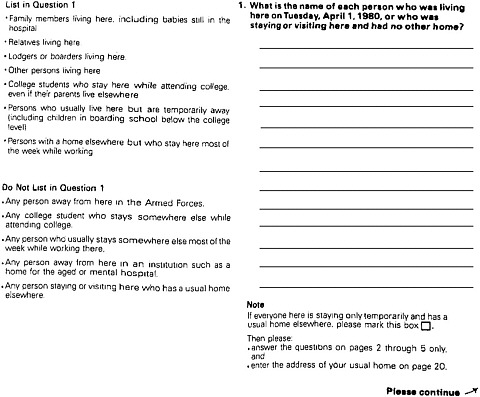

As noted in Box 5-5, the 1950 census enumerator instructions were the first to include a detailed itemization of persons to include or exclude from the census. That approach clearly carried over to the 1960 instructions to respondents on the “Advance Census Report” mailed to households (Figure 6-1). The “PLEASE BE SURE TO LIST” and “DO NOT LIST” categories dominate the instructions at the top of the form, and overwhelm the basic “usual residence” statements at far left under “PLEASE LIST.” Other features of note in the 1960 instructions for respondents include the unconditional plea about “including babies,” the emphasis on people staying at the household but “who have no other home” (mentioned twice), and the emphasized assurance that college students, military personnel, and persons in institutions would be counted at their other location.

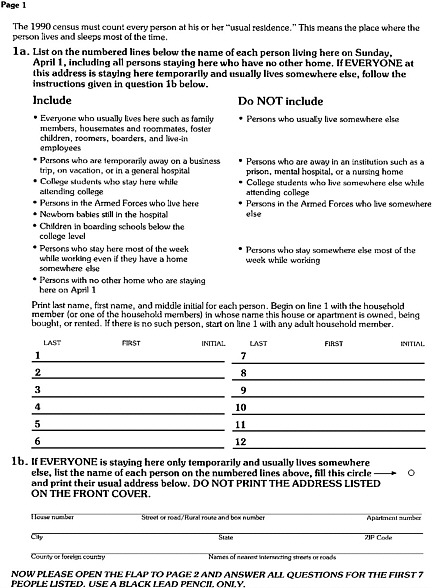

In preparation for the 1970 census—the first to be conducted principally by mailout/mailback—the Census Bureau developed “approximately 700 different questionnaires, field and administrative forms[,] address registers, handbooks, and manuals” for testing between 1961 and 1967. Experiments covered “type styles and sizes, paper and ink colors, as well as [the] formats in which various items would be printed” (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970:4-8). The final version of the 1970 household questionnaire included its residence instructions (Figure 6-2) on a separate page immediately preceding the listing of household members in Question 1. The number of specific include/exclude categories is higher than the number used in 1960,3 though at least one “addition” comes from listing college students twice—to list those living at home

Figure 6-1 Basic residence question, advance materials distributed prior to enumerator visits, 1960 census

NOTE: The specific formatting shown here is from the “Notice of Required Information for the 1960 Census of Population and Housing” form. The header instructions on this version are identical in wording (but slightly different in spacing) on the two variants of Advance Census Reports mailed to households (one for large cities and the other for smaller places). A third variant of the Advance Census Report included a question on citizenship in the tabular array under the instructions; this form—unique to the 1960 census—was used only in New York State, pursuant to a requirement in the state constitution. The same instructions and basic format were also used on the “Were You Counted?” form that persons who believed they had been missed could return to the Census Bureau.

and to exclude those living at school. The choices made in revising the instructions between 1960 and 1970 are interesting:

-

Save for the mention of “persons who usually live here but are temporarily away” and the introduction of the term “usual home elsewhere,” literal mention of “usual” residence is absent; the central instruction is to include “each person who was living here,” not each person who usually lives here.

-

The 1960 instructions on persons staying in the household but who are away temporarily or who have no other place to live have been altered to target two specific groups: boarding school students and commuter workers (persons “who stay here most of the week while working”).

-

The unconditional instruction that babies should be included in the count is now modified to “babies still in the hospital” (and was further modified to “newborn” babies in the 1980 and 1990 censuses).

-

The guidance that college students, military personnel, and institutionalized persons would be counted somewhere else is omitted.

Though awkwardly formatted (tacked on to the end of the “do not list” section), the 1970 questionnaire also introduced a checkbox to indicate that all people at the address in question are only there temporarily.

The include/exclude directions on the 1980 census form (see Figure 6-3) are identical to those used in 1970, save for the dropping of “servants or hired hands living here” as a category of persons to include and a somewhat clearer handling of the “everyone here is staying only temporarily” item. The key difference between the 1980 form and its predecessors is that the earlier forms had respondents jump from a list of instructions directly into rostering and questions. The 1980 form attempted to make respondents work through a preprocessing step—itemizing all the persons belonging to the household in workspace immediately adjacent to the residence instructions (before copying these names to column headings on the next pages of the questionnaire). This layout had the advantage of placing the main residence question in proximity to the instructions associated with it, in contrast with the 1960 and 1970 versions. However, the list of include/exclude instructions that respondents were asked to process could still be interpreted as long and duplicative: for example, college students and commuter workers are referenced in both the include and exclude lists. Sweet (1987:15) criticized the 1980 Question 1:

[It is] very poorly structured. Census respondents have no reason to read all the details regarding who to include and who to exclude. It would seem to be better survey questionnaire practice to force respondents to consider explicitly whether or not each of the various conditions applies to their household.

Figure 6-3 Basic residence question (Question 1), 1980 census questionnaire

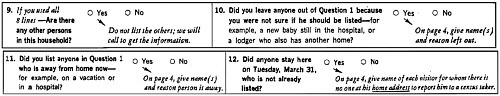

Of the past several censuses, the 1990 census form (see Figure 6-4) devotes the most physical space to the basic household membership question and associated instructions, filling an entire page in the questionnaire booklet. “Usual residence” is prominently described as the census standard at the top of the page—although a reader’s eye is arguably drawn more to the multiple lines of bold-face type introducing question 1a. The wording of nearly all of the include/exclude instructions was revised between 1980 and 1990. Although no new population subgroups are raised as new categories in either list, the new wording of the bullet points revives the specific example of “live-in employees” (to be included), adds “housemates and roommates” in addition to the lodgers and boarders referenced in previous censuses, and makes specific reference to including foster children. Significantly, the 1990 census was the first of the self-enumeration censuses to instruct respondents not to include pris-

oners in household counts. The item flagging cases in which all residents are only staying at the address temporarily is retained, though space to write in (a single) usual address has been added on the same page. Previous censuses effectively cut off the census questioning if the all-temporary condition applied, but the 1990 census had respondents continue with the full questionnaire.

The 2000 census form (which was displayed in Figure 2-1 and is also illustrated as part of Box 6-2) was the product of an extensive design overhaul based on several objectives. Principal among them were the user friendliness of the form (with attention to color and graphical cues to aid navigation) and easier automated data capture and optical character recognition. Like the 1990 form, the 2000 form asks a respondent to go through a preprocessing step, providing a count of people in the household in Question 1 before providing information on them on the subsequent pages. The list of include/exclude instructions is streamlined: college students are no longer mentioned in both categories, and the provision to include “foster children, roomers, or house-mates” consolidates multiple points used in previous censuses. The word “usual” does not appear anywhere in the instructions, though the working definition of usual residence as the place where one lives or stays most of the time is embodied in the last bullet point of both the include and exclude lists. Rather than “usual,” one of the bulleted instructions introduces a different concept—persons staying at the home on Census Day are to be counted there if they do not have another “permanent place to stay.” In terms of physical layout, the 2000 form is different from its predecessors in that the largest part of the instructions for Question 1 (the include/exclude lists) are placed after the answer space, not side by side (as in 1990) or before the answer space (1970 and 1980).

Though the “verbal and visual changes” improved the 2000 questionnaire, Iversen et al. (1999:121) criticize the 2000 census questionnaire development, arguing that “far less research attention was devoted to errors in responses provided by those who answer the census, to the factors that contribute to such errors, and to changes that could contribute to the accuracy and completeness of the information provided by respondents.”

6–D.2

Coverage Probes

In addition to the basic residence question (asking for a count or listing of household members), past decennial censuses have made different use of coverage probe questions. These questions, placed slightly later in the questionnaire, serve to jog respondents’ memories and prompt them to reconsider additions or deletions to the list of household members. Even before the advent of self-enumeration in the census, the 1950 census schedule included such a coverage probe as Housing Item 8: “We have listed (number) persons

who live here. Have we missed anyone away traveling? Babies? Lodgers? Other persons staying here who have no home anywhere else?”

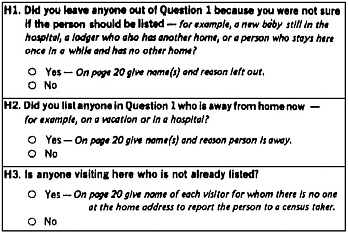

The 1970–1990 censuses included a set of probes on the self-enumeration questionnaire. Figures 6-5 and 6-6 illustrate the probes used in 1970 and 1980, respectively. The 1990 form used two probe questions, omitting the “did anyone stay/visit” question akin to 1980’s H3. An unspoken goal of the questions was to make people reconsider (and revise, as appropriate) the main household roster. Those respondents who wanted to cite specific reasons for including or excluding certain people were directed to a different page in the 1970 and 1980 questionnaires; the 1990 form gave two short lines after the coverage probe questions to write in responses. Mailed questionnaires that had “yes” or blank answers to these questions were flagged for follow-up by district office enumerators.

No such probe was included on the 2000 census questionnaire used in the main mailout/mailback component of the census, but two probes were included on the enumerator questionnaires and used in areas where enumerators conducted direct interviews (see Box 2-2). The same enumerator questionnaires were also used in the nonresponse follow-up and coverage improvement follow-up operations. Question C1 on the 2000 census enumerator form probed for possible undercount, asking, “I need to make sure I have counted everyone who lived or stayed here on April 1, 2000. Did I miss—

-

any children, including foster children?

-

anyone away on business or vacation?

-

any roomers or housemates?

-

anyone else who had no other home?”

Question C2—aimed at possible overcount or duplication—asked, “The Census Bureau has already counted certain people so I don’t want to count them again here. On April 1, 2000, were any of the people you told me about—

-

away at college?

-

away in the Armed Forces?

-

in a nursing home?

-

in a correctional facility?”

In both cases, a “yes” answer meant that the enumerator was supposed to check “yes” and then make alterations in the roster in Question 1, indicating in spaces there whether the entry was an “add” or a “cancel” due to an answer to the probes. However, Nguyen and Zelenak (2003) found that the completed questionnaires show that the enumerators did not follow the procedures fully; only 21.8 percent of forms answering “yes” to C1 has someone listed on the roster with the “add” box checked. Likewise, only 43.4 percent of “yes” returns to C2 showed someone with “cancel” marked. Accordingly,

Figure 6-6 Coverage probes (Questions H1–H3), 1980 census questionnaire

Nguyen and Zelenak (2003) caution about making inference about the nature of people added or deleted based on the questions. Overall, based on checked “add” and “cancel” boxes, the coverage probes resulted in 77,050 people being added to the census and 83,160 deleted. Some impressions from the data are of interest even if they are merely suggestive—nearly 60 percent of the people added were young (ages 0 to 24) and nearly 70 percent of the deletes were aged 15–24, possibly college students who had been listed in the initial roster.

6–D.3

Foreign Census Questionnaires

Appendix B summarizes the approaches taken by censuses in selected foreign countries, including the specific residence instructions and questions on the questionnaires. In terms of the presentation of concepts to respondents, some basic impressions from a review of these other censuses include the following:

-

Some national censuses have been able to develop layout and question wording in order to effectively guide respondents through a series of questions while economizing the amount of space devoted to instructions and the overall length of the questionnaire. The Swiss (person-level, not household-level) and New Zealand census forms are largely instruction free, with the bilingual (English and Maori) New Zealand form promoting effective flow through a streamlined questionnaire.

-

There is considerable variation in the space dedicated to instructions. The Canadian census instrument for 2001 is comparable to the instruction-heavy 1990 U.S. census form, with bulleted include/exclude

-

instructions taking up a full page. (Those listings do suggest different choices and priorities between the two countries, such as the prominent treatment of children in joint custody arrangements and refugees on the Canadian form.) The 2001 United Kingdom census form devotes a full page to instructions and rostering of household members (and, separately, short-term visitors). Though it is still a rather large presentation, the United Kingdom form is a remarkably concise distillation of formal residence definitions and rules that are—if anything—more elaborate than the U.S. residence rules (see Appendix B).

-

It is not unusual for multiple residence questions to be asked and additional address information collected on the census form. The Australia and New Zealand de facto censuses also ask for usual residence information, and the Swiss form asks for two addresses (and includes a check box to indicate which is the place where “you usually reside (4 or more days a week)” in a small amount of physical space on the page. (Again, the Swiss form is completed by each person, not each household.)

-

Some of the forms include reminders or cues to respondents, in addition to the standard instructions. The most prominent example of these is the New Zealand census form that—despite being light on formal instructions—makes repeated entreaties to respondents to be sure to include babies in the report. The Canadian census form for 2001 includes the reminder that the respondent be sure to include himself/herself in the count.

6–D.4

Alternative Questionnaire Tests and Approaches

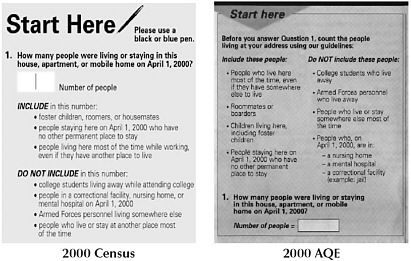

The 1980, 1990, and 2000 decennial censuses each included an Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE) as part of their programs of testing and experimentation. Samples of census households (between 42,000 and 50,000 households in 1990 and 2000) received forms that differed in various ways from those received in all other households. The 1980 experiment focused mainly on variations on matrix-style forms most conducive to the electronic data-capture technology used at the time. The 1990 AQE was the most ambitious of the three; its experimental panels included completely redesigned versions of the census long form as well as radical structures, such as a kit of personal-response census forms rather than a single household form (DeMaio and Bates, 1992).

The 2000 AQE included experimental groups that assessed the impact of graphical and narrative instructions to guide the flow through the census long form; it also contained a group that repeated the census race and Hispanic origin questions in their 1990 form (for contrast with the 2000 version, which introduced the option of multiple-race reporting and restructured the ques-

tions generally). For the purposes of this report, the component of the 2000 AQE that is of most interest is one that varied the initial residence/roster instructions.

Box 6-2 illustrates the specific roster instructions tested by the 2000 AQE, side by side with the residence question asked on the standard census form. The revised questionnaire constituted a bundle of at least 10 changes, from the bluntly worded “master” instruction statement (to count people “using our guidelines”) to finer variations (placing the broader category of “people who live here most of the time” rather than a more specific group as the first item in the include list). Bureau analysis ultimately concluded that the 2000 AQE form worked at least as well as the standard form, yielding a slight improvement in overall response to question 1 and negligible differences in mail return rates. A small reinterview program suggested that the AQE form may have improved coverage (fewer omissions) in some areas, but effects on duplication were negligible (Gerber et al., 2002; Martin et al., 2003). However, as a consequence of its design, the 2000 AQE was not a controlled experiment that could lead to clear answers to such general design questions as:

-

What happens when the instructions come before or after the question, or when they come before or after the answer space?

-

Will people skip the instructions when they come first and instead go right to an item labeled with the number 1?

-

Does a general summary or instruction statement improve understanding of the inclusion and exclusion instructions?

-

Does it matter which inclusion or exclusion criteria come first?

As an operational trial, the 2000 AQE indicated that the alternative form worked at least as well as the regular form, but it did not provide information on exactly why it worked.

6–D.5

Toward 2010: Mid-Decade Census Tests

In preparation for the 2010 census, the Census Bureau laid out a plan of large-scale tests, alternating between mailout-only tests (not involving field follow-up for nonresponding households) and full-field operational trials in successive years. Mailout-only tests were scheduled for 2003 and 2005 and field tests in 2004 and 2006, culminating in the final dress rehearsal in 2008. Subsequently, the Bureau also created an ad hoc mailout-only test for 2006, run in addition to the 2006 field test.

In terms of directions for the residence instructions and questions on the 2010 form, major developments began with the 2005 test; questionnaires were to be sent by mail and responses by either mail or by the Internet were planned, but no follow-up interviewing was performed. Initial proposals for

the 2005 test were presented to and discussed by the panel at its first meeting in July 2004. At that time, we raised the criticism that the 2005 test as planned did not include a control group, a benchmark against which the other alternatives could be evaluated. Feasible choices for the control group would be either the question-instruction combination used in the 2000 census itself or in the 2000 AQE.

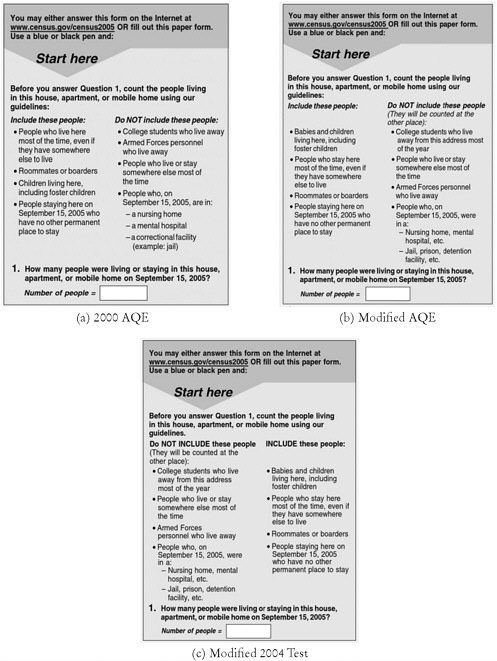

In response, the Bureau adjusted the test plan to include six different versions of the Question 1 residence instruction/household count box, as illustrated in Figure 6-7:

-

a version matching the 2000 AQE;4

-

a modification to the AQE form, adding (and placing at the top of the include list) an item for babies and young children, reordering and revising the include/exclude lists, and reinstating (for the first time since 1960) the assurance that “excluded” persons like college students will be counted at their other place of residence;

-

a revision of the format used in the 2004 census test, identical in content to the modified AQE except that the placement of the include and exclude lists are reversed;

-

a “centralized” treatment that begins with a statement of objectives;

-

a “principle-based” version that attempts a statement of the include/exclude bullet points as basic principles; and

-

a “worksheet” approach, splitting the total “household count” into finer components, developed after the panel’s July 2004 meeting consistent with ideas raised in that public discussion.

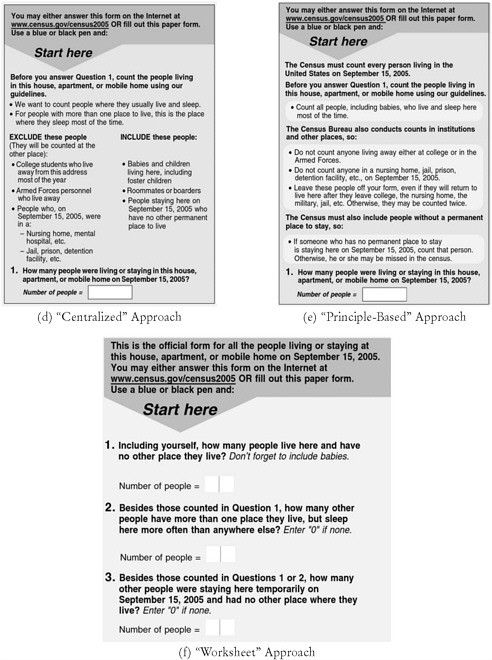

Candidate sets of coverage probe questions were developed in advance of the test, and two sets of probes—each consisting of one question intended to address possible situations of undercount and one about overcount (duplication)—were also included in the tests. These probes are shown in Figure 6-8.5 One set pairs an undercount question—listing possible categories, but not permitting write-in space for explanations (as in probes used in previous censuses)—with a question asking whether each person “sometimes” lives or stays in another place. The second set of probes includes a query specifically about people who have recently moved (into our out of) the housing unit; it

|

4 |

Close examination of the 2000 AQE question in Box 6-2 and the version shown in panel (a) of Figure 6-7 reveals that the two are not completely identical. The graphical “Start here” element is slightly different and combined with the directions on how to respond; the exact spacing and layout of items are slightly discrepant. The 2005 test form also has a blue tint as the questionnaire color, rather than 2000’s orange. |

|

5 |

An interesting difference between these 2005 probes and the ones used in earlier censuses is the reversal of answer categories; in the 2005 versions, “No” is listed as an option before “Yes.” |

also asks whether and why each person “sometimes” lives or stays somewhere else, but goes further to ask the city and state of this other residence.

At this writing, the results of the 2005 National Census Test have not yet been made available. The Bureau has released a report on cognitive testing of the “worksheet” approach (Hunter and de la Puente, 2005), along with the other questionnaire design features being tried in the 2005 test (e.g., layout changes in checkbox response areas to cut down on physical space and revised instructions on the race and Hispanic origin questions). The study was based on 14 cognitive interviews, conducted in the Washington, DC area in January 2005. It concluded that the worksheet approach generally worked well; with a single exception, the numbers reported in the initial questions matched the number of people for which data were collected on the form.6 The Bureau authors expressed concern that the worksheet form might cause some increase in duplication, particularly among commuter workers, and suggested using the phrasing “live and sleep here” in Question 1.

While the 2005 test was in progress, the Bureau scheduled a further mail-based test to be conducted in early 2006, in addition to the broad-scale field test already planned for 2006. Due to its timing, this ad hoc test did not build directly from the results of the 2005 test; the Question 1 box planned for the 2006 test instruments would use the “centralized” approach from the 2005 test. The 2006 ad hoc test was to be focused on two different cues to respondents: (1) the effect of specifying a “deadline” for return on the outside envelopes, cover letter, advance letter, and reminder postcards sent to respondents; (2) more relevant to residence data collection, variations on probes included in a section labeled “final questions for everyone” at the end of the census questionnaire. Treatment groups included a direct question on whether the number of household members specified at the beginning of the form was the same as the number for which data had been recorded throughout the form and, if not, why. Some instructions for this final question block included reminders to respondents to make sure that he or she had counted themselves on the form, as well as babies and temporary guests with no other place to live.

6–E

CHANGING THE STRATEGY: GETTING THE RIGHT RESIDENCE INFORMATION

At the 1986 COPAFS residence rules conference, Mann (1987:5) commented on the fundamental difficulty of the Census Bureau’s instruction-based method of collecting residence count information. “What is printed in

Question 1 has to be clear and it has to be comprehensive. This is not an easy task for a questionnaire designer,” and “the accuracy of the head count largely rests upon the” quality of Question 1 and its instructions. When instructions are read and understood by respondents (as is not universally the case), seemingly small changes in the wording and ordering of instructions can have large or unintended consequences. It is impossible to create a specific instruction for every possible living situation—like the creation of specific formal residence rules for every contingency—and difficulties may arise from mentioning some groups but not others.

At that conference, Hill (1987:3) offered an alternative approach: “listing people where they are staying on the Census date but then regrouping them into their usual residence.” Though “the outlined alternative would give the more reliable overall count,” Hill concluded that it would not be feasible given the technology available in 1980 and 1990. Due to the “massive matching problems” involved with searching reported usual residence information against other census records, the count might be improved but “the reliability of the final geographic allocation might be worse.”

Based on our review of current survey methods, we favor an approach to the decennial census based on asking guided questions—and multiple questions, as necessary—rather than relying on instructions to convey complex definitions. Like Hill’s speculative strategy from 1986, the basic goal of our approach is to shift the burden of deciding what constitutes “usual residence” from the census respondent to the Bureau. The ideal form is one that gathers information without the need for elaborate instruction—and collects sufficient information from respondents to allow the Bureau to make determinations of “usual residence” (by applying residence principles and through matching to relevant census records) during processing and editing.

This question-based approach is an immediate corollary to our recommended residence principles—in particular, the principle that determination of what constitutes “usual” residence should be made at the level of the individual. Achievement of that principle is possible only if sufficient information to make an individual-level determination is collected by the census.

6–E.1

Questions, Not Instructions

The instructions on the 2000 census form are front-loaded onto the basic household count requested in Question 1. That count is supposed to match the number of persons for whom data are recorded in the rest of the questionnaire (if not, or if the household count exceeds 12, follow-up by an enumerator is triggered). Accordingly, the structure of the opening, Question 1, section of the questionnaire is the one that would have to change the most in a revised approach.

The “worksheet” treatment fielded in the 2005 test (see Figure 6-7) is an example of the question-based structure we envision for Question 1, breaking the complex cognitive task of determining a complete household count into smaller (and ideally more tractable) components, such as those persons staying at the household temporarily on Census Day. The intended effect is to replace dense instructions with a guided series of questions. The text of the questions should be concise and so harder to cursorily scan or skip.

It should be emphasized that the specific “worksheet” form tested in 2005 is not the only possible configuration of questions, nor may it be the optimal one. We also emphasize that the same warning that applied to the development of specific residence rules applies here: just as it is confusing and undesirable to carve out a new residence rule for every possible living situation and population group, so too is it unwise to divide the task of deriving a household count across too many questions and categories.

6–E.2

The Short Form Is Too Short

In addition to a revised structure of the basic household count and listing question at the beginning of the census questionnaire, a fully question-based strategy for gathering accurate residence information requires additional queries in the body of the questionnaire. Such additional questions are necessary to obtain enough information to make an individual-level “usual residence” determination and to make sure that a respondent is being counted at the correct place.

The assertion that “the short form is too short” is a strong one and is meant to draw attention to the need for some additional data collection; to be clear, though, we do not suggest a radical lengthening of the form. Followup interviews like the Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation interview used in 2000, or the planned coverage follow-up operation for 2010 (see Chapter 8), can include an entire battery of residence-related questions. It is proper that these highly detailed interviews ask numerous residence questions, while the question content of the census itself is kept more limited.

Two basic conceptual checks need to be made in order to determine whether a person’s enumeration location (that is, where the questionnaire finds them) is where they should be counted in the census:

-

Does this person have a residence elsewhere that could be considered their usual residence?

-

Is this census address correct, for this person and this building (physical structure)?

These two concerns prompt the questions we suggest adding to the census questionnaire. There is also a need for reinstating coverage probes to the cen-

sus questionnaire, to jog respondents’ memories and to provide further clues to census staff on the appropriate resolution of “usual residence.”

“Any Residence Elsewhere” Collection

For the 1900 census—decades before self-response questionnaires, when the census was still conducted by enumerators recording entries in large, columnar ledgers—enumerators received a unique instruction. Concerning “inmates of hospitals or other institutions,” the instructions directed that all such inmates should be enumerated. However, the instruction concluded, “if they have some other permanent place of residence, write it in the margin of the schedule on the left-hand side of the page.” What, if anything, was done with any such information scrawled on the margins is unknown.

As described in Chapter 3, practice varied over subsequent decades as to whether such groups as hospital patients and military personnel stationed at domestic bases (but living in an off-base property) were to be counted at the institution or base or at another place. The spirit of the 1900 instruction and later experience ultimately led to the practice of “usual home elsewhere” (UHE) data collection. A major part of what limited organization exists in the formal residence rules of the 2000 census is the idea of reporting another address as a UHE, a privilege that the rules granted to some types of group quarters residents but not others. (However, as we will discuss in Chapter 7, the Individual Census Reports used for group quarters data collection asked for a UHE from all residents; only the information from members of permitted groups was further processed.) In recent censuses, UHE reporting has been solely limited to the group quarters population, with the exception of the provision in the 1970–1990 censuses of a checkbox for indicating that everyone at the address has a usual place of residence elsewhere and is only staying at the questionnaire address temporarily. Under those conditions only, the 1980–1990 versions asked for the full street address of the other place of residence.

The collection of accurate residence data is central to the census mandate, and the living situations in which people have legitimate, strong ties to more than one residence is not limited to the group quarters population. Collecting information on another place of residence, if applicable, for all persons on the census form better equips the Census Bureau to determine where each individual should be counted, as well as making the structure of the census form’s residence questions more consistent with real-life settings. The Census Bureau should strive to collect alternative residence (address) information from all census respondents, not a selected subset.

Recommendation 6.2: Information on “any residence elsewhere” (ARE) should be collected from census respondents. This in-

formation should include the specific street address of the other residence location. A follow-up question should ask whether the respondent considers this ARE location to be their usual residence, the place where they live or sleep more than any other place.

To be clear, we do not suggest by this recommendation that the decennial census questionnaire attempt to collect a complete residential history of each person in the household. Rather, what we suggest is that the census form allow the entry of a single street address of an ARE where a person may spend a significant portion of a week, month, or year. As stated in the recommendation, a follow-up question should ask whether the respondent considers this alternate address their “usual” residence. Another follow-up question could include other categories to be specified, such as whether the alternate address is a seasonal or vacation home or a family home (e.g., for college students or commuter workers).7 The objective of this approach is not to produce a full profile of mobility in the United States, but to further the basic objective of the census: to allow census clerks to determine the appropriate location for counting, to provide specific information for the detection of duplicates or omissions in the census, and to flag cases for which personal follow-up by an enumerator would be helpful. For research purposes, a more extensive battery of residence questions would be helpful: however, that should be the goal of a revised Living Situation Survey (Recommendation 5.5) or other moderate-scale surveys (as we discuss in Chapter 8), not the census form itself.

This collection of ARE information is consistent with the approach of some foreign censuses, which collect both a respondent’s de jure usual residence as well as the de facto information about where they were (and were enumerated) on Census Day. The principal justification for the addition of the ARE question is similar to that used in these foreign censuses: it is information that is used to help determine that a person’s usual residence is recorded correctly and to help ensure that each person is counted once and only once.

Lowry (1987) advocated adopting this approach in the U.S. census, collecting both de jure and de facto addresses, at the 1986 COPAFS residence rules conference. Discussants at that workshop held this idea to be “definitely a good one” (Hill, 1987:4). The conference summary (CEC Associates, 1987:25) concurred with the collection of UHE information but also noted that “there may be major technical-procedural limitations on the implementation of” said recommendations:

The Census Bureau has limited resources with which to check all those reporting a UHE back to the referenced address to ensure that they were

indeed counted at home, and limited time before 1990 in which to acquire computer capacity to facilitate such matches…. The costs and complexities of introducing these procedures increase the importance of identifying those groups for which follow-up of UHE reports is most likely to be productive and cost-effective.

Computational capacity is a lesser concern now than in 1986, and the coverage evaluation research program for the 2000 census was a showcase for improved searching and matching capability. Ultimately, Bureau staff were able to learn much about the nature of potential duplicate records in the census by performing a complete match of the census returns against themselves based mainly on person name and date of birth (Fay, 2002b, 2004). This methodology is a good base for improvements in 2010 and beyond. The method was sufficiently tractable that the Bureau is considering “real-time unduplication” based on similar matches while census processing is still in progress (and while capacity exists to deploy enumerators for follow-up interviews). These developments suggest that the sheer technical capacity to collect and process additional reports of address information is at hand.

However, other logistical concerns—limited field follow-up resources (to resolve discrepancies found during matching or to validate addresses not on the Master Address File) and the time constraint of producing apportionment counts by the end of the census year—carry great weight. Although we conclude that universal provision for ARE reporting is the proper direction for the census to follow, we also recognize the need for testing and evaluation of new procedures before they are applied in the census; our recommendations in Section 6–E.4 reflect these constraints.

One of the coverage probes tested in the 2005 National Census Test (Figure 6-8, (b), Question 10) is close to an ARE question, though it asks only for the place (city/state) where the person’s other residence is located. The two Question 10 probes are a starting point for part of an ARE question (or an immediate follow-up to it), asking about the nature of the other residence (e.g., vacation home or school-location address for a college student) or the reason that the person resides there some of the time (e.g., seasonal move or commuter worker). Ideally, the ARE location can be obtained along with some indication of how much time the person spends at the other location so that usual residence can be determined.

Our proposed ARE question does not go as far as some researchers of seasonal “snowbird” populations—or demographers, generally, interested in the dynamics of migration—would like. With specific eye toward collecting data on “snowbirds,” Happel and Hogan (2002) suggest a question akin to: “Besides your usual place of residence, have you spent 30 days or more during the past year at another locale? If so, at which location(s) did you stay and for how long (in each location)?” The structure of this question—a full residence profile for each person—also speaks to a limitation of the request for a single

ARE per person: such an approach would still not capture the full experience of intensive travelers, migrant workers, and recreational vehicle users with ties to more than two places. However, a universal ARE option at least breaks free from the notion that respondents must specify one, single place of residence and could provide greater accuracy in the many cases—college students, hospital patients, children in joint custody arrangements, and so forth—where the tension in reporting is between two places.

Verifying Addresses

Current census methodology makes the strong—and sometimes erroneous—assumption that the census questionnaire is properly delivered to the correct housing unit (and to the people who live there). In multiunit structures like apartment buildings, questionnaires may be placed in the wrong unit’s mailbox by mistake. Particularly for large multi-unit structures with a common mail delivery point, mail carriers may also view the census questionnaires as interchangeable (for better or worse, like high-volume advertising or “junk” mail) and put them in mailboxes haphazardly. The sheer volume of the major census mailout in a decennial year can contribute to the perception of the questionnaires as interchangeable, when in fact they are intended to reflect input from a specific designated housing unit. Improper sorting or misplacement prior to giving the mail to letter carriers can lead to questionnaires being delivered to the wrong house.

The 2000 census questionnaire lacked a provision for a respondent to indicate that the address printed on the received questionnaire was erroneous, or that the questionnaire was misdelivered. This has not always been the case. The 1970 census questionnaire—the first administered primarily by mail—included a three-line address box; directly underneath, an italicized instruction read: “If the address shown above has the wrong apartment identification, please write the correct apartment number or location here.” One line was provided for response. The 1980 mailing label space shared the same feature and identical copy (save that the entry space was above, not below, the printed label); three lines were provided for entry. Foreign censuses (see Appendix B) generally do not offer guidance on or examples of such a correction question, yet whether self-administered or conducted by an interviewer, they direct a respondent to write in full address information rather than relying only on a printed address label.

Providing space for respondents to advise of changes to the address printed on their census form is a relatively simple change, but it would entail some cost. Depending on its exact implementation, respondents’ handwritten corrections would likely be ill suited to automatic optical character recognition; accordingly, the burden of data entry would be shifted to human clerks (working with the raw paper forms or, more likely, scanned images). How-

ever, we believe that this cost would be offset by potential gains in the quality of data reporting and assignment of reported persons and households to particular housing units. It would also provide very valuable input for census follow-up, unduplication, and coverage evaluation efforts, and it would also provide useful operational data for evaluation (e.g., quantitative evidence of the magnitude of some mail delivery problems).

Recommendation 6.3: The census questionnaire should allow respondents to correct the address printed on the form if it is wrong (e.g., address is listed incorrectly or questionnaire is delivered to wrong unit or apartment number).

In addition to mail delivery problems, even questionnaires delivered correctly to the right address may not reach the “right” people. Prominent among these cases are seasonal residences that may be vacant for much of the year or are not consistently occupied by the same people over a year. The occupants of a home in February or March may receive the form—response to which is compelled by law—yet they have no mechanism in the current short form for indicating that their stay at the address in question is only temporary (and that they may correctly be counted elsewhere). People who move residences on or near Census Day may also face the problem of a correctly delivered questionnaire finding them at the “wrong” address. A questionnaire could be carried with the movers from the old housing unit to the new one, or it may be inadvertently forwarded.

One approach to handling this problem could be to borrow from the 1990 census example and add a follow-up question to the address correction space—to provide checkboxes to indicate that all residents of the indicated housing units are there temporarily or are in the process of moving residences. The use of such a checkbox flag could be useful in identifying cases that need follow-up from an enumerator. However, we believe a better approach would involve collecting the address information for the other residence location (as did Question 1b on the 1990 census form; see Figure 6-4); this is entirely consistent with the broader change in residence questions that we describe in the next section.

Coverage and Housing Type Probes

We are encouraged that the 2005 test suggests that the Census Bureau is considering adding separate coverage probe questions, which were absent on the streamlined 2000 census questionnaire. As we discuss in Chapter 8, the Bureau’s interest in probe questions is partly operational, because responses to the probes are intended to trigger eligibility for an enhanced coverage followup operation; see Box 6-3. In addition to addressing these practical concerns, the use of coverage probe questions is beneficial in its own right; the questions

|

Box 6-3 Coverage Follow-Up Plans for the 2010 Census Plans for the 2010 coverage follow-up operation call for an expansion of the coverage improvement follow-up operation from 2000 (Moul, 2003). The revised operation would be triggered to prompt follow-up enumeration if

The problems of implementing this are two-fold: first, the fraction of census returns for whom this operation would be triggered might be too large to be workable (e.g., reinterview of 30 percent rather than 10 percent), and second, it may conflict with the postenumeration survey conducted as part of coverage measurement. |

provide further opportunity to elicit residence information through questions rather than relying on a preamble of instructions.

We note above that some of the probes used in the 2005 National Census Test are useful starts to follow-up questions to accompany a reported “any residence elsewhere” address. The presence of such a question, related to the basic nature of a housing unit, is particularly essential given the short-form-only orientation of the 2010 census; the standard question on housing tenure (own or rent) may be the only question focused on the housing unit itself and the people living in it. In general, we agree with the approach taken in past censuses, which was the basic goal of formulating possibilities for the 2005 test: it is essential that separate probes targeting overcount (potential duplicates) and undercount (possible omissions) be included on the census form.

6–E.3

Mode Effects

There is another compelling reason that the Bureau should adopt a question-based framework for data collection, particularly the basic count in Question 1. It is well known from research on surveys that differences in the mode of administration of a census or survey can influence responses. The experience of answering a survey questionnaire from a human interviewer standing in one’s doorway is substantively different than that of an interview

conducted in the less personal interface of a phone call. The rapport and trust between interviewer and respondent, the perceived level of “security” in answering private queries, and the impulse to decline to answer some questions (or cut off an interview altogther) differ between the two modes, which in turn are different from the effects of responding through the impersonal media of mailed questionnaires or the Internet. Survey modes also differ in their ability to present instructions and support information.

The decennial census has become a mixed-mode survey collection of vast proportion and will likely continue on that path. In 2000, responses were acquired through self-enumeration on paper questionnaires and through computer-assisted telephone interview if respondents called a number for assistance. Response to the census short form was also possible on the Internet though this option was not widely publicized. In 2010, mail and self-response will continue to be the bulk of the census response. However, the Bureau plans to conduct nonresponse follow-up data collection using computer-assisted personal interviewing on a handheld device; in 2000, follow-up interviews were conducted using paper forms. In the initial planning for the 2010 census, data collection by the Internet and by telephone using an automated “interactive voice response” system were expected to be major parts of the census process (National Research Council, 2004b), but this is no longer so. The interactive voice response system appeared to perform badly in the 2003 National Census Test, and the Bureau acknowledged in June 2006 that it planned to scrap Internet data collection.8

There is reason to believe that a question-based mode of collecting residence information may be more robust to mode differences than an instruction-based model, because response to instructions may depend crucially on medium of administration. We emphasize, though, that this is an empirical question, a supposition which requires testing of the form we call for in Chapter 8.

Recommendation 6.4: Regardless of the final structure of residence questions chosen for 2010, research must be done on response effects created by mode of administration (mail, phone, Internet, interview with handheld computers).

6–E.4

Testing ARE in 2010

Some elements of a question-based approach to gathering residence information are already in testing, such as the coverage probe questions and the

“worksheet” prototype for Question 1 on the 2005 census test. The most complicated part of the approach—placing an ARE item on the 2010 census questionnaire—is certainly feasible for 2010. However, effective plans for how to work with ARE data in processing census returns and scheduling enumerator follow-up as necessary are vitally important to the resulting census data. In the interests of keeping the 2008 census dress rehearsal as true a rehearsal as possible (and not a major experiment), the Bureau should test a question-based approach as part of the experimentation program of the 2010 census, in order to provide a base of information for further research over the next decade and possible inclusion in 2020.

Recommendation 6.5: In the 2010 census, the Census Bureau should conduct a major experiment to test a form that asks a sufficient number of residence questions to determine the residence situation of each person, rather than requiring respondents to follow complicated residence instructions in formulating their answers. The results of this test, and associated research, should guide decision on full implementation of the approach in 2020.

As we recommend in Chapter 7, ARE address data should be included on the questionnaires used to enumerate all elements of the group quarters and other nonhousehold population in 2010, and those data should be fully evaluated and used in unduplication screening as appropriate. As has been done in previous censuses, a sample of the household population should receive a question-based form with ARE items.

From a research standpoint, it would be useful for evaluations of the collected ARE data to compare the results of this test with those of the census coverage follow-up program, in which more detailed residence probes and rostering questions are possible than on the regular census form. If possible, field reinterviews with some test respondents would be useful, perhaps using a traditional instruction-based form to see if the same results are obtained.